Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Hemoglobinopathy

View on Wikipedia| Hemoglobinopathy | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Hemoglobinopathies |

| |

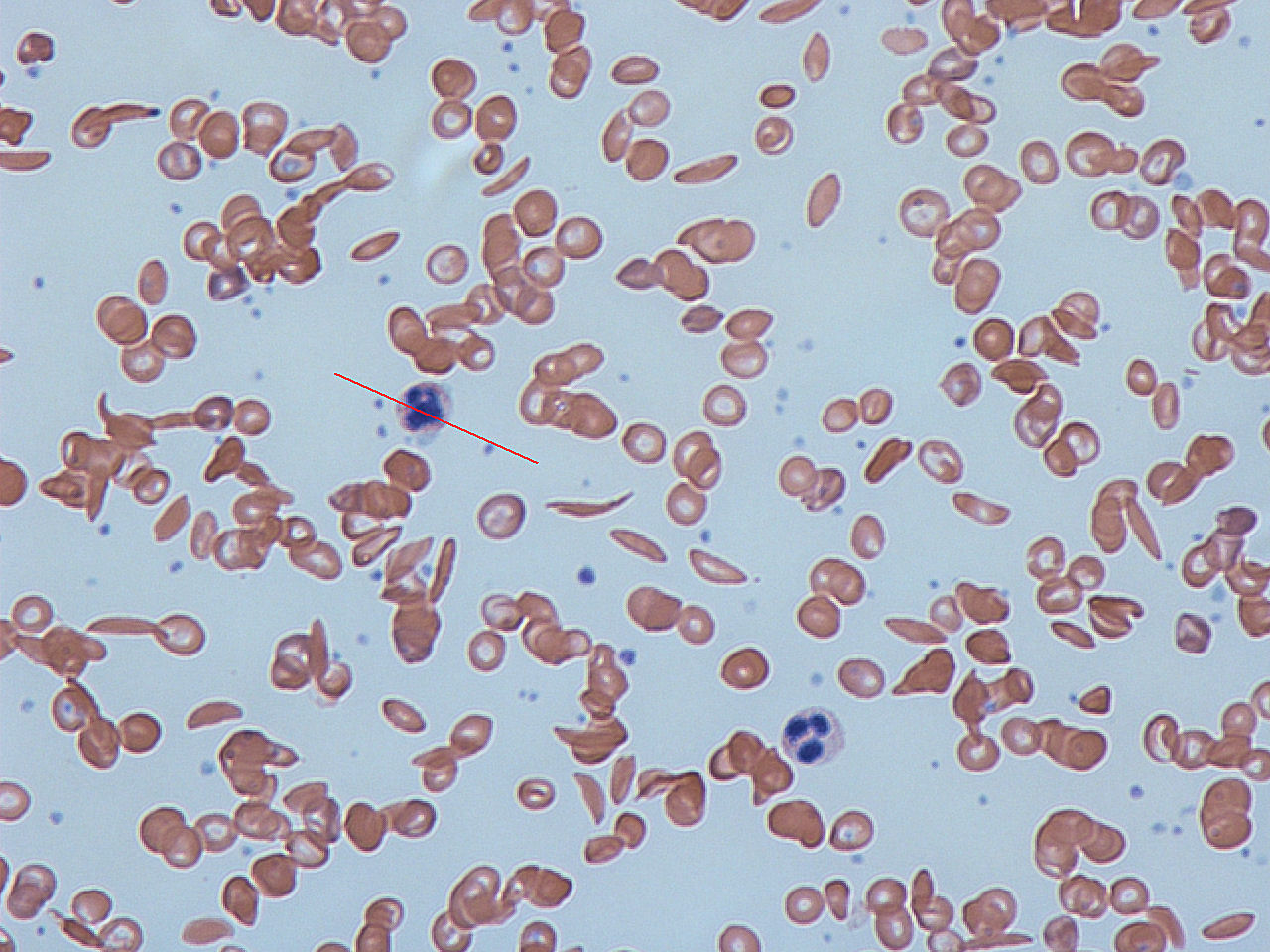

| Red blood cells from a person with sickle cell disease, illustrating abnormal 'sickle' shaped red blood cells - key characteristic of the disease. | |

| Specialty | Hematology |

| Symptoms | Chronic anemia |

| Complications | Enlarged spleen, iron overload, death |

| Usual onset | During fetal development or very early infancy |

| Types | Relatively frequent: sickle cell disease, alpha thalassemia and beta thalassemia |

| Causes | Inherited disease |

| Diagnostic method | Blood smear, ferritin test, hemoglobin electrophoresis, DNA sequencing |

| Differential diagnosis | Iron deficiency anemia |

| Prevention | Genetic counselling of potential parents, termination of pregnancy |

| Treatment | Blood transfusion, iron chelation, hematopoietic stem cell transplant |

Hemoglobinopathy is the medical term for a group of inherited blood disorders involving the hemoglobin, the major protein of red blood cells.[1] They are generally single-gene disorders and, in most cases, they are inherited as autosomal recessive traits.[2][3]

There are two main groups: abnormal structural hemoglobin variants caused by mutations in the hemoglobin genes, and the thalassemias, which are caused by an underproduction of otherwise normal hemoglobin molecules. The main structural hemoglobin variants are HbS, HbE and HbC. The main types of thalassemia are alpha-thalassemia and beta thalassemia.[4][2]

Hemoglobin functions

[edit]Hemoglobin is a protein containing iron that facilitates the transportation of oxygen in red blood cells.[5] Hemoglobin in the blood carries oxygen from the lungs to the other tissues of the body, where it releases the oxygen to enable aerobic respiration which powers the metabolism. Normal levels of hemoglobin vary according to sex and age in the range 9.5 to 17.2 grams of hemoglobin in every deciliter of blood.[6]

Hemoglobin also transports other gases. It carries off some of the body's respiratory carbon dioxide (about 20–25% of the total)[7] as carbaminohemoglobin, in which CO2 binds to the heme protein. The molecule also carries the important regulatory molecule nitric oxide bound to a thiol group in the globin protein, releasing it at the same time as oxygen.[8]

Hemoglobin structural biology

[edit]

Normal human hemoglobins are tetrameric proteins composed of two pairs of globin chains, each of which contains one alpha-like (α) globin and one beta-like (β) globin. Each globin chain is associated with an iron-containing heme moiety. Throughout life, the synthesis of the α and the β chains is balanced so that their ratio is relatively constant and there is no excess of either type.[9]

The specific α and β chains that are incorporated into Hb are highly regulated during development:[10]

- Embryonic Hb are expressed as early as four to six weeks of embryogenesis and disappear around the eighth week of gestation as they are replaced by fetal Hb.[11][12] Embryonic Hbs include:

- Hb Gower-1, composed of two ζ (zeta) globins and two ε (epsilon) globins, i.e., ζ2ε2

- Hb Gower-2, composed of two α globins and two ε globins (α2ε2)

- Hb Portland, composed of two ζ globins and two γ (gamma) globins (ζ2γ2)

- Fetal Hb (HbF) is produced from approximately eight weeks of gestation through birth and constitutes approximately 80 percent of Hb in the full-term neonate. It declines during the first few months of life and, in the normal state, constitutes <1 percent of total Hb by early childhood. HbF is composed of two α globins and two γ globins (α2γ2).[13]

- Adult Hb (HbA) is the predominant Hb in children by six months of age and onward; it constitutes 96-97% of total Hb in individuals without a hemoglobinopathy. It is composed of two α globins and two β globins (α2β2).[14]

- HbA2 is a minor adult Hb that normally accounts for approximately 2.5–3.5% of total Hb from six months of age onward. It is composed of two α globins and two δ (delta) globins (α2δ2).[14]

Classification of hemoglobinopathies

[edit]A) Qualitative

[edit]Structural abnormalities

[edit]Hemoglobin structural variants manifest a change in the structure of the Hb molecule. The majority of hemoglobin variants do not cause disease and are most commonly discovered either incidentally or through newborn screening. Hb variants can usually be detected by protein-based assay methods such as electrophoresis,[15] isoelectric focusing,[16] or high-performance liquid chromatography.[17] Diagnosis is commonly confirmed by DNA sequencing.[18]

The hemoglobin structural variants can be broadly classified as follows:[19]

- Sickle cell disorders, which are the most prevalent form of hemoglobinopathy. Sickle hemoglobin (HbS) is prone to polymerize when deoxygenated, precipitating within the red blood cell. This damages the RBC membrane resulting in its premature destruction and consequent anemia.[20]

- Unstable hemoglobin variants are mutations that cause the hemoglobin molecule to precipitate, spontaneously or upon oxidative stress, resulting in hemolytic anemia. Precipitated, denatured hemoglobin can attach to the inner layer of the plasma membrane of the red blood cell (RBC) forming Heinz bodies, leading to premature destruction of the RBC and anemia.[21]

- Change in oxygen affinity. High or low oxygen affinity hemoglobin molecules are more likely than normal to adopt the relaxed (R, oxy) state or the tense (T, deoxy) state, respectively. High oxygen affinity variants (R state) cause polycythemia (e.g., Hb Chesapeake, Hb Montefiore). Low oxygen affinity variants can cause cyanosis (e.g., Hb Kansas, Hb Beth Israel).[22]

Chemical abnormalities

[edit]Methemoglobinemia is a condition caused by elevated levels of methemoglobin in the blood. Methaemoglobin is a form of hemoglobin that contains the ferric [Fe3+] form of iron, instead of the ferrous [Fe2+] form . Methemoglobin cannot bind oxygen, which means it cannot carry oxygen to tissues. In human blood a trace amount of methemoglobin is normally produced spontaneously; the enzyme methemoglobin reductase is responsible for converting methemoglobin back to hemoglobin.[23][24] Methemoglobinemia can be hereditary but more commonly occurs as a side effect of certain medications or by abuse of recreational drugs.[25]

B) Quantitative

[edit]Production abnormalities

[edit]

Thalassemias are quantitative defects that lead to reduced levels of one type of globin chain, creating an imbalance in the ratio of alpha-like chains to beta-like chains. This ratio is normally tightly regulated to prevent excess globin chains of one type from accumulating. The excess chains that fail to incorporate into normal hemoglobin can form non-functional aggregates that precipitate. This can lead to premature RBC destruction in the bone marrow and/or in the peripheral blood. Thalassemia subtypes of clinical significance are alpha thalassemia and beta thalassemia. A third subtype, delta thalassemia, affects production of HBA2 and is generally asymptomatic.[26]

The severity of alpha thalassemia depends on how many of the four genes that code for alpha globin are faulty. In the fetus, a deficiency of alpha globin results in the production of Hemoglobin Barts - a dysfunctional hemoglobin that consists of four gamma globins. In this situation, a fetus will develop hydrops fetalis and normally die before or shortly after birth.[27] In adults alpha thalassemia manifests as HbH disease. In this, excess beta-globin forms β4-tetramers, which accumulate and precipitate in red blood cells, damaging their membranes. Damaged RBCs are removed by the spleen resulting in moderate to severe anemia.[28]

In beta thalassemia, reduced production of beta globin, combined with a normal synthesis of alpha globin, results in an accumulation of excess unmatched alpha globin. This precipitates in the red cell precursors in the bone marrow, triggering their premature destruction. Anemia in beta thalassemia results from a combination of ineffective production of RBCs, peripheral hemolysis, and an overall reduction in hemoglobin synthesis.[29]

Combination hemoglobinopathies

[edit]A combination hemoglobinopathy occurs when someone inherits two different abnormal hemoglobin genes. If these are different versions of the same gene, one having been inherited from each parent it is an example of compound heterozygosity.

Both alpha- and beta- thalassemia can coexist with other hemoglobinopathies. Combinations involving alpha thalassemia are generally benign.[30][31]

Some examples of clinically significant combinations involving beta thalassemia include:

- Hemoglobin C/ beta thalassemia: common in Mediterranean and African populations generally results in a moderate form of anemia with splenomegaly.[32]

- Hemoglobin D/ beta thalassemia: common in the northwestern parts of India and Pakistan (Punjab region).[33]

- Hemoglobin E/ beta thalassemia: common in Cambodia, Thailand, and parts of India, it is clinically similar to β thalassemia major or β thalassemia intermedia.[34]

- Hemoglobin S/ beta thalassemia: common in African and Mediterranean populations, it is clinically similar to sickle-cell anemia.[35]

- Delta-beta thalassemia is a rare form of thalassemia in which there is a reduced production of both the delta and beta globins. It is generally asymptomatic.[36]

There are two clinically significant combinations involving the sickle cell gene:

- Hemoglobin S/ beta thalassemia: (see above).[35]

- Hemoglobin S/ hemoglobin C (Hemoglobin SC disease) occurs when an individual inherits one gene for hemoglobin S (sickle cell) and one gene for hemoglobin C, The symptoms are very similar to sickle cell disease.[37]

Hemoglobin variants

[edit]Hemoglobin variants are not necessarily pathological. For example, Hb Lepore-Boston and G-Waimanalo are two variants which are non-pathological.[38] There are in excess of 1,000 known hemoglobin variants.[39] A research database of hemoglobin variants is maintained by Penn State University.[40] A few of these variants are listed below.

Normal hemoglobins

[edit]Source:[2]

- Embryonic

- HbE Gower 1 (ζ2ε2) present in the normal embryo.[41]

- HbE Gower 2 (α2ε2) present in the normal embryo.[41]

- HbE Portland I (ζ2γ2) present in the normal embryo.[42]

- Fetal

- HbF/Fetal (α2γ2) dominating during pregnancy and reducing close to zero a few weeks after birth

- HbA (α2β2) Adult hemoglobin, present in small quantities during pregnancy

- Adult

- HbA (α2β2) comprising approximately 97% of adult hemoglobin

- HbA2 (α2δ2) comprising approximately 3% of adult hemoglobin

- HbF/Fetal (α2γ2) dominating during pregnancy and reducing close to zero after birth

Relatively common abnormal hemoglobins

[edit]Source:[2]

Evolutionary advantage

[edit]

Some hemoglobinopathies seem to have given an evolutionary benefit, especially to heterozygotes, in areas where malaria is endemic. Malaria parasites infect red blood cells, but subtly disturb normal cellular function and subvert the immune response. A number of mechanisms have been proposed to explain the increased chance of survival for the carrier of an abnormal hemoglobin trait.[43]

References

[edit]- ^ CDC (2019-02-08). "Hemoglobinopathies Research". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 2019-05-05.

- ^ a b c d Weatherall, D. J.; Clegg, J. B. (2001). "Inherited haemoglobin disorders: An increasing global health problem". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 79 (8): 704–712. PMC 2566499. PMID 11545326.

- ^ Shakeel, Hassan (25 March 2023). "Thalassaemia — Knowledge Hub". Genomics Education Programme and NHS England. Retrieved 2025-01-01.

- ^ "Hemoglobinopathies and Thalassemia". medicalassistantonlineprograms.org/. Archived from the original on 2015-01-09. Retrieved 2013-11-07.

- ^ Maton, Anthea; Jean Hopkins; Charles William McLaughlin; Susan Johnson; Maryanna Quon Warner; David LaHart; Jill D. Wright (1993). Human Biology and Health. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, US: Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-981176-0.

- ^ "Hemoglobin: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 2025-01-02.

- ^ Patton, Kevin T. (2015-02-10). Anatomy and Physiology. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 978-0-323-31687-3. Archived from the original on 2016-04-26. Retrieved 2016-01-09.

- ^ Epstein, F. H.; Hsia, C. C. W. (1998). "Respiratory Function of Hemoglobin". New England Journal of Medicine. 338 (4): 239–47. doi:10.1056/NEJM199801223380407. PMID 9435331.

- ^ Weatherall DJ. The New Genetics and Clinical Practice, Oxford University Press, Oxford 1991.

- ^ Cantú, Ileana; Philipsen, Sjaak (2014-11-01). "Flicking the switch: adult hemoglobin expression in erythroid cells derived from cord blood and human induced pluripotent stem cells". Haematologica. 99 (11): 1647–1649. doi:10.3324/haematol.2014.116483. ISSN 1592-8721. PMC 4222461. PMID 25420279.

- ^ Huisman TH. The structure and function of normal and abnormal haemoglobins. In: Baillière's Clinical Haematology, Higgs DR, Weatherall DJ (Eds), W.B. Saunders, London 1993. p.1.

- ^ Natarajan K, Townes TM, Kutlar A. Disorders of hemoglobin structure: sickle cell anemia and related abnormalities. In: Williams Hematology, 8th ed, Kaushansky K, Lichtman MA, Beutler E, et al. (Eds), McGraw-Hill, 2010. p.ch.48.

- ^ Schechter AN (November 2008). "Hemoglobin research and the origins of molecular medicine". Blood. 112 (10): 3927–38. doi:10.1182/blood-2008-04-078188. PMC 2581994. PMID 18988877.

- ^ a b "Hemoglobinopathies". Brigham and Women's Hospital. 17 April 2002. Retrieved 2009-02-06.

- ^ "Hemoglobin Electrophoresis: MedlinePlus Medical Test". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 2024-11-20.

- ^ Garfin, David E. (1990), Deutscher, Murray P. (ed.), "[35] Isoelectric focusing", Methods in Enzymology, Guide to Protein Purification, 182, Academic Press: 459–477, doi:10.1016/0076-6879(90)82037-3, ISBN 978-0-12-182083-1, PMID 2314254, retrieved 2024-11-20

- ^ Arishi, Wjdan A.; Alhadrami, Hani A.; Zourob, Mohammed (2021-05-05). "Techniques for the Detection of Sickle Cell Disease: A Review". Micromachines. 12 (5): 519. doi:10.3390/mi12050519. PMC 8148117. PMID 34063111.

- ^ Arishi, Wjdan A.; Alhadrami, Hani A.; Zourob, Mohammed (2021-05-05). "Techniques for the Detection of Sickle Cell Disease: A Review". Micromachines. 12 (5): 519. doi:10.3390/mi12050519. PMC 8148117. PMID 34063111.

- ^ Forget, Bernard G.; Bunn, H. Franklin (2013-02-01). "Classification of the Disorders of Hemoglobin". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine. 3 (2) a011684. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a011684. ISSN 2157-1422. PMC 3552344. PMID 23378597.

- ^ Eaton, William A.; Hofrichter, James (1990). "Sickle Cell Hemoglobin Polymerization". Advances in Protein Chemistry. 40: 63–279. doi:10.1016/S0065-3233(08)60287-9. ISBN 978-0-12-034240-2. PMID 2195851.

- ^ Srivastava, P.; Kaeda, J. S.; Roper, D.; Vulliamy, T. J.; Buckley, M.; Luzzatto, L. (1995). "Severe hemolytic anemia associated with the homozygous state for an unstable hemoglobin variant (Hb Bushwick)". Blood. 86 (5): 1977–1982. doi:10.1182/blood.V86.5.1977.bloodjournal8651977. PMID 7655024.

- ^ Percy, M. J.; Butt, N. N.; Crotty, G. M.; Drummond, M. W.; Harrison, C.; Jones, G. L.; Turner, M.; Wallis, J.; McMullin, M. F. (2009). "Identification of high oxygen affinity hemoglobin variants in the investigation of patients with erythrocytosis". Haematologica. 94 (9): 1321–1322. doi:10.3324/haematol.2009.008037. PMC 2738729. PMID 19734427.

- ^ Ludlow JT, Wilkerson RG, Nappe TM (January 2019). "Methemoglobinemia". StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 30726002.

- ^ Elahian F, Sepehrizadeh Z, Moghimi B, Mirzaei SA (June 2014). "Human cytochrome b5 reductase: structure, function, and potential applications". Critical Reviews in Biotechnology. 34 (2): 134–143. doi:10.3109/07388551.2012.732031. PMID 23113554.

- ^ "Methemoglobinemia (MetHb): Symptoms, Causes & Treatment". Cleveland Clinic. Archived from the original on 2024-12-29. Retrieved 2025-01-01.

- ^ Dasgupta, Amitava (2014-01-01), "Chapter 21 - Hemoglobinopathy", Clinical Chemistry, Immunology and Laboratory Quality Control, San Diego: Elsevier, pp. 363–390, doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-407821-5.00021-8, ISBN 978-0-12-407821-5, retrieved 2025-01-01

- ^ "Pathophysiology of alpha thalassemia". www.uptodate.com. Retrieved 2016-08-30.

- ^ Fucharoen, Suthat; Viprakasit, Vip (2009-01-01). "Hb H disease: clinical course and disease modifiers". Hematology. 2009 (1): 26–34. doi:10.1182/asheducation-2009.1.26. ISSN 1520-4391. PMID 20008179.

- ^ Thein, Swee Lay (2005-01-01). "Pathophysiology of β Thalassemia—A Guide to Molecular Therapies". Hematology. 2005 (1): 31–37. doi:10.1182/asheducation-2005.1.31. ISSN 1520-4391.

- ^ Khatri, Govinda; Sahito, Abdul Moiz; Ansari, Saboor Ahmed (2021-12-31). "Shared molecular basis, diagnosis, and co-inheritance of alpha and beta thalassemia". Blood Research. 56 (4): 332–333. doi:10.5045/br.2021.2021128. PMC 8721464. PMID 34776416.

- ^ Wambua, Sammy; Mwacharo, Jedidah; Uyoga, Sophie; Macharia, Alexander; Williams, Thomas N. (2006). "Co-inheritance of α+-thalassaemia and sickle trait results in specific effects on haematological parameters". British Journal of Haematology. 133 (2): 206–209. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06006.x. ISSN 1365-2141. PMC 4394356. PMID 16611313.

- ^ "Hemoglobin C" (PDF). Washington State Department of Health. February 2011.

- ^ Torres Lde S (March 2015). "Hemoglobin D-Punjab: origin, distribution and laboratory diagnosis". Revista Brasileira de Hematologia e Hemoterapia. 37 (2): 120–126. doi:10.1016/j.bjhh.2015.02.007. PMC 4382585. PMID 25818823.

- ^ Olivieri, Nancy F.; Muraca, Giulia M.; O'Donnell, Angela; Premawardhena, Anuja; Fisher, Christopher; Weatherall, David J. (May 2008). "Studies in haemoglobin E beta-thalassaemia". British Journal of Haematology. 141 (3): 388–397. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07126.x. ISSN 0007-1048. PMID 18410572.

- ^ a b Gerber, Gloria F. (April 2024). "Hemoglobin S–Beta-Thalassemia Disease - Hematology and Oncology". MSD Manual Professional Edition. Retrieved 2024-12-24.

- ^ Pal, G. K. & (2005). Textbook Of Practical Physiology - 2Nd Edn. Orient Blackswan. p. 53. ISBN 978-81-250-2904-5. Retrieved 17 September 2016.

- ^ Pitone, Melanie L. "Hemobglobin SC Disease (for Parents)". Nemours Foundation. Retrieved 2024-12-24.

- ^ DiGeorge, Nicholas W.; Lahey, Colleen F.; Vigilante, John A. (2014-03-01). "Fitness for Duty: Two Cases of Rare Hemoglobin Variants in U.S. Navy Recruits". Military Medicine. 179 (3): e354 – e356. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-13-00383. ISSN 0026-4075.

- ^ "Understanding haemoglobinopathies". Public Health England. 6 July 2018. Retrieved 2024-12-28.

- ^ "A Database of Human Hemoglobin Variants and Thalassemia mutations". Penn State University. December 2024.

- ^ a b Manning, Lois R.; Russell, J. Eric; Padovan, Julio C.; Chait, Brian T.; Popowicz, Anthony; Manning, Robert S.; Manning, James M. (2007). "Human embryonic, fetal, and adult hemoglobins have different subunit interface strengths. Correlation with lifespan in the red cell". Protein Science. 16 (8): 1641–1658. doi:10.1110/ps.072891007. ISSN 1469-896X. PMC 2203358. PMID 17656582.

- ^ Manning, Lois R.; Russell, J. Eric; Padovan, Julio C.; Chait, Brian T.; Popowicz, Anthony; Manning, Robert S.; Manning, James M. (2007). "Human embryonic, fetal, and adult hemoglobins have different subunit interface strengths. Correlation with lifespan in the red cell". Protein Science. 16 (8): 1641–1658. doi:10.1110/ps.072891007. ISSN 1469-896X. PMC 2203358. PMID 17656582.

- ^ Taylor, Steve M.; Cerami, Carla; Fairhurst, Rick M. (2013-05-16). "Hemoglobinopathies: Slicing the Gordian Knot of Plasmodium falciparum Malaria Pathogenesis". PLOS Pathogens. 9 (5) e1003327. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1003327. ISSN 1553-7374. PMC 3656091. PMID 23696730.