Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Cyanosis

View on Wikipedia| Cyanosis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Cyanosis of the hand of a patient with low oxygen saturations | |

| Specialty | Pulmonology, cardiology |

| Symptoms | Hypothermia, numbness in the area where the cyanosis is, coughing, wheezing, difficulty breathing |

| Types | Circumoral, central, peripheral |

| Causes | Airway problems, lung problems, heart problems, exposure to extreme cold |

| Differential diagnosis | Circumoral cyanosis, peripheral cyanosis, central cyanosis |

| Prevention | Avoid exposure to freezing cold temperatures, limit smoking or caffeine, avoid touching cyanide |

| Medication | Antidepressants, anti-hypertension medication, or if caused by other reasons, naloxone hydrochloride |

Cyanosis is the change of tissue color to a bluish-purple hue, as a result of decrease in the amount of oxygen bound to the hemoglobin in the red blood cells of the capillary bed.[1] Cyanosis is apparent usually in the body tissues covered with thin skin, including the mucous membranes, lips, nail beds, and ear lobes.[1] Some medications may cause discoloration such as medications containing amiodarone or silver. Furthermore, mongolian spots, large birthmarks, and the consumption of food products with blue or purple dyes can also result in the bluish skin tissue discoloration and may be mistaken for cyanosis.[2][3] Appropriate physical examination and history taking is a crucial part to diagnose cyanosis. Management of cyanosis involves treating the main cause, as cyanosis is not a disease, but rather a symptom.[1]

Cyanosis is further classified into central cyanosis and peripheral cyanosis.

Pathophysiology

[edit]

The mechanism behind cyanosis is different depending on whether it is central or peripheral.

Central cyanosis

[edit]Central cyanosis occurs due to decrease in arterial oxygen saturation (SaO2), and begins to show once the concentration of deoxyhemoglobin in the blood reaches a concentration of ≥ 5.0 g/dL (≥ 3.1 mmol/L or oxygen saturation of ≤ 85%).[4] This indicates a cardiopulmonary condition.[1]

Causes of central cyanosis are discussed below.

Peripheral cyanosis

[edit]Peripheral cyanosis happens when there is increased concentration of deoxyhemoglobin on the venous side of the peripheral circulation. In other words, cyanosis is dependent on the concentration of deoxyhemoglobin. Patients with severe anemia may appear normal despite higher-than-normal concentrations of deoxyhemoglobin. While patients with increased amounts of red blood cells (e.g., polycythemia vera) can appear cyanotic even with lower concentrations of deoxyhemoglobin.[5][6]

Causes

[edit]Central cyanosis

[edit]Central cyanosis is often due to a circulatory or ventilatory problem that leads to poor blood oxygenation in the lungs. It develops when arterial oxygen saturation drops below 85% or 75%.[5]

Acute cyanosis can be a result of asphyxiation or choking and is one of the definite signs that ventilation is being blocked.

Central cyanosis may be due to the following causes:

- Central nervous system (impairing normal ventilation):[5]

- Respiratory system:[1][5]

- Cardiovascular system:[1][5]

- Hemoglobinopathies:[5]

- Methemoglobinemia[a]

- Sulfhemoglobinemia[b]

- Polycythemia

- Congenital cyanosis (HbM Boston) arises from a mutation in the α-codon which results in a change of primary sequence, H → Y. Tyrosine stabilizes the Fe(III) form (oxyhaemoglobin) creating a permanent T-state of Hb.

Peripheral cyanosis in an individual with peripheral vascular disease.

- Others:

- High altitude, cyanosis may develop in ascents to altitudes >2400 m.[1][5]

- Hypothermia[5]

- Frostbite[7]

- Obstructive sleep apnea[5]

- ^ Note this causes "spurious" cyanosis, in that, since methemoglobin appears blue, the patient can appear cyanosed even in the presence of a normal arterial oxygen level.

- ^ Note a rare condition in which there is excess sulfhemoglobin (SulfHb) in the blood. The pigment is a greenish derivative of hemoglobin which cannot be converted back to normal, functional hemoglobin. It causes cyanosis even at low blood levels.

Peripheral cyanosis

[edit]Peripheral cyanosis is the blue tint in fingers or extremities, due to an inadequate or obstructed circulation.[5] The blood reaching the extremities is not oxygen-rich and when viewed through the skin a combination of factors can lead to the appearance of a blue color. All factors contributing to central cyanosis can also cause peripheral symptoms to appear, but peripheral cyanosis can be observed in the absence of heart or lung failures.[5] Small blood vessels may be restricted and can be treated by increasing the normal oxygenation level of the blood.[5]

Peripheral cyanosis may be due to the following causes:[5]

- All common causes of central cyanosis

- Reduced cardiac output (e.g., heart failure or hypovolemia)

- Cold exposure

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

- Arterial obstruction (e.g., peripheral vascular disease, Raynaud phenomenon)

- Venous obstruction (e.g., deep vein thrombosis)

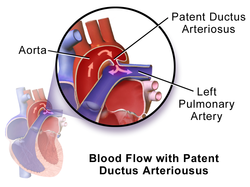

Differential cyanosis

[edit]

Differential cyanosis is the bluish coloration of the lower but not the upper extremity and the head.[5] This is seen in patients with a patent ductus arteriosus.[5] Patients with a large ductus develop progressive pulmonary vascular disease, and pressure overload of the right ventricle occurs.[8] As soon as pulmonary pressure exceeds aortic pressure, shunt reversal (right-to-left shunt) occurs.[8] The upper extremity remains pink because deoxygenated blood flows through the patent duct and directly into the descending aorta while sparing the brachiocephalic trunk, left common carotid, and left subclavian arteries.

Evaluation

[edit]A detailed history and physical examination (particularly focusing on the cardiopulmonary system) can guide further management and help determine the medical tests to be performed.[1] Tests that can be performed include pulse oximetry, arterial blood gas, complete blood count, methemoglobin level, electrocardiogram, echocardiogram, X-Ray, CT scan, cardiac catheterization, and hemoglobin electrophoresis.

In newborns, peripheral cyanosis typically presents in the distal extremities, circumoral, and periorbital areas.[9] Of note, mucous membranes remain pink in peripheral cyanosis as compared to central cyanosis where the mucous membranes are cyanotic.[9]

Skin pigmentation and hemoglobin concentration can affect the evaluation of cyanosis. Cyanosis may be more difficult to detect on people with darker skin pigmentation. However, cyanosis can still be diagnosed with careful examination of the typical body areas such as nail beds, tongue, and mucous membranes where the skin is thinner and more vascular.[1] As mentioned above, patients with severe anemia may appear normal despite higher than normal concentrations of deoxyhemoglobin.[5][6] Signs of severe anemia may include pale mucosa (lips, eyelids, and gums), fatigue, lightheadedness, and irregular heartbeats.

Management

[edit]Cyanosis is a symptom, not a disease itself, so management should be focused on treating the underlying cause.

If it is an emergency, management should always begin with securing the airway, breathing, and circulation. In patients with significant respiratory distress, supplemental oxygen (in the form of nasal canula or continuous positive airway pressure depending on severity) should be given immediately.[10][11]

If the methemoglobin levels are positive for methemoglobinemia, first-line treatment is to administer methylene blue.[1]

History

[edit]The name cyanosis literally means the blue disease or the blue condition. It is derived from the color cyan, which comes from cyanós (κυανός), the Greek word for blue.[12]

It is postulated by Dr. Christen Lundsgaard that cyanosis was first described in 1749 by Jean-Baptiste de Sénac, a French physician who served King Louis XV.[13] De Sénac concluded from an autopsy that cyanosis was caused by a heart defect that led to the mixture of arterial and venous blood circulation. But it was not until 1919, when Dr. Lundsgaard was able to derive the concentration of deoxyhemoglobin (8 volumes per cent) that could cause cyanosis.[13]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Adeyinka, Adebayo; Kondamudi, Noah P. (2021), "Cyanosis", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 29489181, retrieved 2021-10-28

- ^ Dereure, Olivier (2001). "Drug-Induced Skin Pigmentation: Epidemiology, Diagnosis and Treatment". American Journal of Clinical Dermatology. 2 (4): 253–262. doi:10.2165/00128071-200102040-00006. ISSN 1175-0561. PMID 11705252. S2CID 22892985.

- ^ Conlon, Joseph D; Drolet, Beth A (2004). "Skin lesions in the neonate". Pediatric Clinics of North America. 51 (4): 863–888. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2004.03.015. PMID 15275979.

- ^ Mini Oxford Handbook of Clinical Medicine (7th ed.). p. 56.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Pahal P, Goyal A (July 2020). "Central and Peripheral Cyanosis". StatPearls. PMID 32644593.

- ^ a b McMullen, Sarah M.; Patrick, Ward (2013-03-01). "Cyanosis". The American Journal of Medicine. 126 (3): 210–212. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.11.004. ISSN 0002-9343. PMID 23410559. S2CID 244083635.

- ^ Basit, H.; Wallen, T. J.; Dudley, C. (2021). "Frostbite". StatPearls. StatPearls. PMID 30725599.

- ^ a b Gillam-Krakauer, Maria; Mahajan, Kunal (2021), "Patent Ductus Arteriosus", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 28613509, retrieved 2021-11-19

- ^ a b Lees, Martin H. (1970). "Cyanosis of the newborn infant". The Journal of Pediatrics. 77 (3): 484–498. doi:10.1016/S0022-3476(70)80024-5. PMID 5502102.

- ^ Ramji, Siddarth (2013), "Neonatal Resuscitation", IAP Textbook of Pediatrics, Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers (P) Ltd., p. 28, doi:10.5005/jp/books/11894_109, ISBN 9789350259450, retrieved 2021-11-05

- ^ Sasidharan, Ponthenkandath (2004). "An approach to diagnosis and management of cyanosis and tachypnea in term infants". Pediatric Clinics of North America. 51 (4): 999–1021. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2004.03.010. ISSN 0031-3955. PMID 15275985.

- ^ Mosby's Medical, Nursing & Allied Health Dictionary. Mosby-Year Book (4th ed.). 1994. p. 425.

- ^ a b Lundsgaard, C. (1919-09-01). "Studies on Cyanosis". The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 30 (3): 259–269. doi:10.1084/jem.30.3.259. ISSN 0022-1007. PMC 2126682. PMID 19868357.