Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Port Huron, Michigan

View on Wikipedia

Port Huron is a city in and the county seat of St. Clair County, Michigan, United States.[4] The population was 28,983 at the 2020 census. The city is bordered on the west by Port Huron Township, but the two are administered autonomously.

Key Information

Port Huron is located along the source of the St. Clair River at the southern end of Lake Huron. The city is along the Canada–United States border and directly across the river from Sarnia, Ontario. The two cities are connected by the Blue Water Bridge at the eastern terminus of Interstate 69/Interstate 94. Port Huron has the easternmost point of land in the state of Michigan and is also one of the northernmost areas included in the Detroit–Warren–Dearborn Metropolitan Statistical Area (Metro Detroit).

History

[edit]

This area was long occupied by the Ojibwa people. French colonists had a temporary trading post and fort at this site in the 17th century.

In 1814, following the War of 1812, the United States established Fort Gratiot at the base of Lake Huron. A community developed around it. The early 19th century was the first time a settlement developed here with a permanent European-American population. In the 19th century, the United States established an Ojibwa reservation in part of what is now Port Huron, in exchange for their cession of lands under treaty for European-American settlement. But in 1836, under Indian Removal, the US forced the Ojibwa to move west of the Mississippi River and resettle in what are now the states of Wisconsin and Minnesota.[5]

In 1857, Port Huron became incorporated. Its population grew rapidly after the 1850s due a high rate of immigration: workers leaving poverty, famine, and revolutions in Europe were attracted to the successful shipbuilding and lumber industries in Michigan. These industries supported development around the Great Lakes and in the Midwest. In 1859 the city had a total of 4,031 residents; some 1,855, or 46%, were foreign-born or their children (first-generation Americans).[6]

By 1870, Port Huron's population exceeded that of surrounding villages. In 1871, the State Supreme Court designated Port Huron as the county seat of St. Clair County.[7]

On October 8, 1871, the city, as well as places north in Sanilac and Huron counties, burned in the Port Huron Fire of 1871. A series of other fires leveled Holland and Manistee, as well as Peshtigo, Wisconsin and Chicago, Illinois on the same day. The Thumb Fire that occurred a decade later, also engulfed Port Huron.

In 1895 the village of Fort Gratiot, in the vicinity of the former Fort Gratiot, was annexed by the city of Port Huron.[8]

The following historic sites have been recognized by the State of Michigan through its historic marker program.

- Fort St. Joseph. The fort was built in 1686 by the French explorer Duluth. This fort was the second European settlement in lower Michigan. This post guarded the upper end of the St. Clair River, the vital waterway joining Lake Erie and Lake Huron. Intended by the French to bar English traders from the upper lakes, the fort in 1687 was the base of a garrison of French and Indian allies. In 1688 the French abandoned this fort. The site was incorporated into Fort Gratiot in 1814. A park has been established at the former site of the fort.

- Fort Gratiot Light. The Fort Gratiot Lighthouse was built in 1829 to replace a tower destroyed by a storm. In the 1860s workers extended the tower to its present height of 84 feet (26 m). The light, automated in 1933, continues to guide shipping on Lake Huron into the narrow and swift-flowing St. Clair River. It was the first lighthouse established in the State of Michigan.

- Lightship Huron. From 1935 until 1970, the Huron was stationed in southern Lake Huron to mark dangerous shoals. After 1940 the Huron was the only lightship operating on the Great Lakes. Retired from Coast Guard Service in 1970, she was presented to the City of Port Huron in 1971.

- Grand Trunk Railway Depot. The depot, which is now part of the Port Huron Museum, is where 12-year-old Thomas Edison departed daily on the Port Huron–Detroit run. In 1859, the railroad's first year of operation, Edison convinced the railroad company to let him sell newspapers and confections on the daily trips. He became so successful that he soon placed two newsboys on other Grand Trunks running to Detroit. He made enough money to support himself and to buy chemicals and other experimental materials.

- Port Huron Public Library. In 1902 the city of Port Huron secured money from philanthropist Andrew Carnegie to erect a municipal library and arranged for matching operating funds. In 1904, a grand Beaux-Arts-style structure was built at a cost of $45,000. At its dedication, Melvil Dewey, creator of a widely used book classification system, delivered the opening address. The Port Huron Public Library served in its original capacity for over sixty years. In 1967, a larger public library was constructed. The following year the former library was renovated and re-opened as the Port Huron Museum of Arts and History. An addition was constructed in 1988.

- Harrington Hotel. The hotel opened in 1896 and is a blend of Romanesque, Classical and Queen Anne architecture. The hotel closed in 1986, but a group of investors bought the structure that same year to convert it into housing for senior citizens. The Harrington Hotel is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

- Grand Trunk Western Railroad Tunnel. The tunnel was opened in 1891 and links Port Huron with Canada. This international submarine railway tunnel was the first international tunnel in the world. The tunnel's total length is 6,025 feet (1,836 m), with 2,290 feet (700 m) underwater. The tunnel operations were electrified in 1908; half a century later they were converted to use diesel fuel. Tracks were lowered in 1949 to accommodate larger freight cars. During World War I, a plot to blast the tunnel was foiled. A new tunnel has since been opened.

The city was hit by a violent F4 tornado on May 21, 1953, damaging or destroying over 400 structures, killing two, and injuring 68.

The city received the All-America City Award in 1955 and 2005.

In June 1962, the Port Huron Statement, a New Left manifesto, was adopted at a convention of the Students for a Democratic Society. The convention did not take place within the actual city limits of Port Huron, but instead was held at a United Auto Workers retreat north of the city (now part of Lakeport State Park). A historical marker will be erected on the site in 2025.[9]

Port Huron is the only site in Michigan where a lynching of an African-American man took place. On May 27, 1889, in the early morning, a mob of white men stormed the county jail to capture 23-year-old Albert Martin. A mixed-race man, he was accused of attacking a woman. They hanged him from the 7th Street Bridge. A memorial was installed in 2018 at the site, recounting Martin's history. The city collaborated with the Equal Justice Initiative on this memorialization.[10]

On November 11, 2017, veterans from around the country, such as Dave Norris, Clitus Schuyler, and Lou Ann Dubuque, joined together at a cemetery in Port Huron to share the significance of Veterans Day.[11][12]

In April 2023, the Pere Marquette Railway bascule bridge was demolished after a nearly decade long battle between preservationists and the Port Huron Yacht Club.[13] Built in 1931, the structure was eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places, and was one of only six similar bridges remaining in the US.[14]

Historic photographs

[edit]-

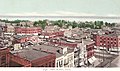

Port Huron c. 1902

-

Huron Avenue in 1912

-

St. Clair Tunnel in 1907

-

Gratiot Lighthouse in 1902

-

Fort Gratiot Lighthouse

-

The Pere Marquette Railway bridge as seen in 2021; it was demolished in 2023.

Geography

[edit]According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 12.26 square miles (31.75 km2), of which 8.08 square miles (20.93 km2) is land and 4.18 square miles (10.83 km2) is water.[15] The city is considered to be part of the Thumb area of East-Central Michigan, also called the Blue Water Area. The easternmost point (on land) of Michigan can be found in Port Huron, near the site of the Municipal Office Center and the wastewater treatment plant. The Black River divides the city in half, snaking through Port Huron and emptying into the St. Clair River near Downtown.

Climate

[edit]Port Huron has a humid continental climate (Köppen climate classification: Dfa) with hot summers, cold winters, and rain or snow in all months of the year.

| Climate data for Port Huron NOAA Station (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1931–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 64 (18) |

69 (21) |

82 (28) |

87 (31) |

96 (36) |

102 (39) |

103 (39) |

102 (39) |

101 (38) |

90 (32) |

81 (27) |

66 (19) |

103 (39) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 51.0 (10.6) |

51.7 (10.9) |

65.1 (18.4) |

77.0 (25.0) |

86.7 (30.4) |

92.0 (33.3) |

93.5 (34.2) |

91.8 (33.2) |

88.7 (31.5) |

79.0 (26.1) |

64.4 (18.0) |

54.0 (12.2) |

95.3 (35.2) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 30.9 (−0.6) |

33.3 (0.7) |

42.2 (5.7) |

54.2 (12.3) |

66.7 (19.3) |

76.4 (24.7) |

81.3 (27.4) |

79.7 (26.5) |

73.1 (22.8) |

60.5 (15.8) |

46.9 (8.3) |

36.0 (2.2) |

56.8 (13.8) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 25.4 (−3.7) |

26.9 (−2.8) |

35.2 (1.8) |

46.1 (7.8) |

57.7 (14.3) |

67.6 (19.8) |

73.3 (22.9) |

71.8 (22.1) |

65.0 (18.3) |

53.2 (11.8) |

41.0 (5.0) |

31.2 (−0.4) |

49.5 (9.7) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 19.9 (−6.7) |

20.5 (−6.4) |

28.3 (−2.1) |

38.0 (3.3) |

48.8 (9.3) |

58.8 (14.9) |

65.2 (18.4) |

64.0 (17.8) |

56.8 (13.8) |

46.0 (7.8) |

35.2 (1.8) |

26.4 (−3.1) |

42.3 (5.7) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 1.1 (−17.2) |

2.8 (−16.2) |

10.8 (−11.8) |

24.4 (−4.2) |

36.2 (2.3) |

46.0 (7.8) |

54.3 (12.4) |

53.3 (11.8) |

42.2 (5.7) |

32.5 (0.3) |

20.2 (−6.6) |

9.7 (−12.4) |

−2.5 (−19.2) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −19 (−28) |

−15 (−26) |

−7 (−22) |

8 (−13) |

21 (−6) |

32 (0) |

35 (2) |

37 (3) |

25 (−4) |

20 (−7) |

2 (−17) |

−7 (−22) |

−19 (−28) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 2.48 (63) |

2.06 (52) |

2.21 (56) |

3.15 (80) |

3.53 (90) |

3.62 (92) |

3.25 (83) |

3.14 (80) |

3.32 (84) |

3.13 (80) |

2.81 (71) |

2.17 (55) |

34.87 (886) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 11.1 (28) |

11.4 (29) |

4.6 (12) |

0.4 (1.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

1.3 (3.3) |

6.7 (17) |

35.5 (90) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 14.0 | 10.3 | 10.8 | 12.9 | 13.0 | 10.9 | 10.1 | 10.3 | 10.1 | 12.6 | 11.8 | 12.7 | 139.5 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 7.4 | 5.9 | 2.9 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.8 | 4.4 | 22.0 |

| Source: NOAA[16][17] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1850 | 1,584 | — | |

| 1860 | 4,371 | 175.9% | |

| 1870 | 5,973 | 36.7% | |

| 1880 | 8,883 | 48.7% | |

| 1890 | 13,543 | 52.5% | |

| 1900 | 19,158 | 41.5% | |

| 1910 | 18,863 | −1.5% | |

| 1920 | 25,944 | 37.5% | |

| 1930 | 31,361 | 20.9% | |

| 1940 | 32,759 | 4.5% | |

| 1950 | 35,725 | 9.1% | |

| 1960 | 36,084 | 1.0% | |

| 1970 | 35,794 | −0.8% | |

| 1980 | 33,981 | −5.1% | |

| 1990 | 33,694 | −0.8% | |

| 2000 | 32,338 | −4.0% | |

| 2010 | 30,184 | −6.7% | |

| 2020 | 28,983 | −4.0% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[18] | |||

Port Huron is the largest city in the Thumb area, and is a center of industry and trade for the region.

2010 census

[edit]As of the census[19] of 2010, there were 30,184 people, 12,177 households, and 7,311 families residing in the city. The population density was 3,735.6 inhabitants per square mile (1,442.3/km2). There were 13,871 housing units at an average density of 1,716.7 per square mile (662.8/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 84.0% White, 9.1% African American, 0.7% Native American, 0.6% Asian, 1.2% from other races, and 4.5% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino residents of any race were 5.4% of the population.

There were 12,177 households, of which 32.5% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 34.5% were married couples living together, 19.9% had a female householder with no husband present, 5.6% had a male householder with no wife present, and 40.0% were non-families. 33.0% of all households were made up of individuals, and 11.8% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.42 and the average family size was 3.03.

The median age in the city was 35.8 years. 25.6% of residents were under the age of 18; 9.9% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 26.3% were from 25 to 44; 25.2% were from 45 to 64; and 13.1% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 47.8% male and 52.2% female.

Culture

[edit]

- The Port Huron Museum is a series of four museums,[20] namely:

- The Great Lakes Maritime Center offers opportunities to learn about the history of the Great Lakes. Freighters pass within 100 feet (30 m) of the glass windows, and there is an underwater live camera feed.

- The Desmond District Demons is a horror film festival, held at the end of October annually. The festival focuses on elevating the horror genre, hosting independent film screenings alongside a Dark Arts Exhibition showcasing local artists.

- The Black River Film Society is a community focused on cultivating the areas independent film screenings and host regular film related events, such as premiering Stockholm (2018 film) in Michigan, Tough Guy: The Bob Probert Story and Sincerely Brenda.

- The School for Strings presents over 50 concerts each year with its Fiddle Club, Faculty, and Student Ensembles. It provides music education across the area.

- Each year, the Port Huron to Mackinac Boat Race is held, with a starting point in Port Huron north of the Blue Water Bridge. The race finishes at Mackinac Island, crossing Lake Huron. It is considered by some boaters to be a companion to the longer Chicago Yacht Club Race to Mackinac.

- The Port Huron Civic Theatre began in 1956 by a group of theater lovers. Since 1983, it has used McMorran Place for its productions.

- The Blue Water Film Festival (2010–2014) was held in the fall, which had notables such as Chris Gore, Sid Haig, Curtis Armstrong, Timothy Busfield, Loni Love, Dave Coulier.

- The main branch of the St. Clair County Library is located in downtown Port Huron. The library contains more than 285,300 books, nearly 200 magazine subscriptions, and over 22,700 books on tape, books on compact disc, music compact discs, cassettes, and videos.

- The International Symphony Orchestra of Sarnia, Ontario and Port Huron, Michigan perform events at McMorran Place, Port Huron Northern Theatre and Temple Baptist Church in Sarnia.

- Encompassing over 100 homes and buildings, the Olde Town Historic District is Port Huron's first and only residential historic district. The Olde Town Historic Neighborhood Association is an organization working to preserve historic architecture in Port Huron. They have hosted an annual historic home tour, flower plantings and beautification and neighborhood Christmas decorations.

- The Welkin Base Ball Club is Port Huron's historic vintage base ball team. Modeled on Port Huron's first baseball club from 1867, the Welkin Base Ball Club re-creates the time of baseball's roots.

Pop culture

[edit]A reference to the Port Huron Statement was made in the Coen Brothers film The Big Lebowski.[22]

In 2009, the TV show Criminal Minds used Port Huron and Detroit as locations for an episode involving crossing the border into Ontario.[23]

Sports

[edit]Port Huron has had a strong tradition of minor league hockey for many years.

The Port Huron Flags played in the original International Hockey League from 1962 to 1981, winning three Turner Cup championships in 1966, 1971 and 1972. Its leading career scorers were Ken Gribbons, who played most of his career in the IHL; Bob McCammon, a lifelong IHLer who went on to be a National Hockey League coach with the Philadelphia Flyers and the Vancouver Canucks; Bill LeCaine and Larry Gould, who played a handful of NHL games with the Pittsburgh Penguins and the Vancouver Canucks, respectively.

Legendary NHL hockey broadcaster Mike Emrick started his career doing play-by-play hockey for the Flags on AM 1450 WHLS in the mid 1970s. Emrick would go on to broadcast Olympic hockey games and Stanley Cup playoffs for NBC Sports, and is a frequent guest contributor to sister station WPHM.[24]

Port Huron was also represented in the Colonial Hockey League (also operating under the names United Hockey League and International Hockey League), with franchises from 1996 until the league folded in 2010. Originally called the Border Cats, the team was renamed the Beacons in 2002, the Flags in 2005 and the Icehawks in 2007. Among the more notable players were Bob McKillop, Jason Firth, Tab Lardner and Brent Gretzky.

The Port Huron Fighting Falcons of the junior North American Hockey League played at McMorran Place, beginning in 2010 until 2013. The team moved to Connellsville, PA for the 2014 season. The team's name was changed to the Keystone Ice Miners.

Port Huron is also home to the Port Huron Prowlers of the Federal Prospects Hockey League.

The Port Huron Pirates indoor football team dominated the Great Lakes Indoor Football League up until their departure to Flint, MI. McMorran Arena once again hosted indoor football with the Port Huron Predators of the Continental Indoor Football League in 2011. The Predators failed to finish the 2011 season, and were replaced in 2012 by the Port Huron Patriots who also participated in the CIFL.

Parks

[edit]The City of Port Huron owns and operates 17 waterfront areas containing 102 acres (0.4 km2) and 3.5 miles (5.6 km) of water frontage. This includes three public beaches and six parks with picnic facilities. The city also has nine scenic turnout sites containing over 250 parking spaces. Port Huron operates the largest municipal marina system in the state and has five separate locations for boat mooring.

The city has 14 public parks, 4 smaller-sized “tot” parks, 19 playgrounds (City owned), 9 playgrounds (School owned), 33 tennis courts, including 16 at schools and 6 indoors, 3 public beaches, 4 public swimming pools, 1 community center, and 1 public parkway.

Government

[edit]The city government is organized under a council–manager government form. The City Council is responsible for appointing a city manager, who is the chief administrative officer of the city. The manager supervises the administrative affairs of the city and carries out the policies established by the City Council. As the Chief Administrative Officer, the City Manager is responsible for the organization of the administrative branch and has the power to appoint and remove administrative officers who are responsible for the operation of departments which carry out specific functions. The City Council consists of seven elected officials—a mayor and six council members. Beginning with the 2011 election, citizens voted separately for Mayor and Council. Council members will serve staggered four-year terms and the mayor will serve a two-year term. The city levies an income tax of 1 percent on residents and 0.5 percent on nonresidents.[25]

The current mayor is Anita Ashford, who was elected in November 2024 to her first two year term after defeating eight term incumbent Pauline Repp.[26]

Port Huron lies in the 64th State House District and is represented by Republican Joseph G. Pavlov. In the State Senate, Port Huron is represented by Dan Lauwers in the 25th State Senate District.

Federally, Port Huron is part of Michigan's 9th Congressional District, represented by Republican Lisa McClain, elected in 2022.

Backyard chicken-keeping

[edit]In early 2025, residents of Port Huron, Michigan, initiated efforts to legalize the keeping of backyard chickens within city limits. Advocates highlighted concerns about food insecurity, noting that approximately one in twelve families in Port Huron struggle with access to nutritious food. They argued that allowing residents to raise chickens could provide a sustainable source of protein and foster community resilience through the sharing of surplus eggs.

On March 10, 2025, the Port Huron City Council discussed a proposal to amend local ordinances to permit residents to keep up to five hens on properties of at least a quarter-acre. Advocates emphasized benefits such as enhanced sustainability, reduced reliance on external food supply chains, and alignment with practices in other Michigan cities like Grand Rapids and Ann Arbor. The proposal included stipulations to address concerns about noise and animal welfare, such as prohibiting roosters and collaborating with the St. Clair County Humane Society to manage complaints.[27]

The ordinance amendment was formally introduced on April 14, 2025, with the City Council voting 6–1 in favor. The proposed regulations specify that hens must be confined in a backyard coop with at least one square foot per bird, accompanied by an enclosed run no larger than eight by eight feet. Coops must be situated at least ten feet from property lines and twenty feet from neighboring residences. The ordinance also mandates daily feeding and watering, regular cleaning to prevent vermin and insect infestations, and prohibits keeping hens inside residences, porches, or attached garages.[28]

These developments in Port Huron reflect a broader trend in Michigan toward supporting urban agriculture and self-sufficiency. State Representative Jim DeSana reintroduced legislation in February 2025 aimed at easing zoning restrictions for backyard chickens, proposing that residents with at least a quarter-acre of residential property be allowed to keep up to five hens per quarter-acre, with a maximum of twenty-five hens. The legislation seeks to bolster food security and reduce grocery expenses for families.[29]

Education

[edit]Economy

[edit]Industry

[edit]Some of Port Huron's earliest industries were related to the agriculture and forest products industry.

Lumbering in the Port Huron region seems to have started on the Black River about 1827. It quickly became the center of the lumbering industry for the region, in which logs from further north in The Thumb could be floated downriver.[30] The continued need to supply Port Huron's sawmills with fresh timber lead to the development the Port Huron and Northwestern Railroad and fueled the city's booming shipbuilding industry.

A large grain elevator was located on the St. Clair River just north of the current Municipal Office Center.[31] A bean dock was located on the St. Clair River, where dry edible beans from points north in the Thumb were loaded into ships. The dock operated as the Port Huron Terminal Company. Currently the bean dock is used as an event venue.[32]

Chicory

[edit]Port Huron was also a national leader in the chicory coffee substitute industry. Future Congressman Henry McMorran in 1902 started Port Huron's chicory processing plant, located on the Black River near 12th Avenue. A second chicory plant operated at 3rd and Court Streets in Port Huron, which would later be purchased by McMorran's son.[33] The roadside weed which grew in areas of the Thumb and Saginaw Valleys was brought to Port Huron for processing and then shipped worldwide. Chicory was commonly used as a coffee substitute especially in wartime.[34]

Munitions

[edit]Wartime also brought another industry to Port Huron: the Mueller Metals Company, which built a factory in Port Huron in 1917. The plant primarily made shell casings for World War I. The factory was originally owned by the Mueller Co., and since has been spun off into its own entity called Mueller Industries.[35] The Port Huron Factory is still in operation, located on Lapeer Road on the city's west side, where they produce a variety of valves and fittings.[36]

Shipbuilding

[edit]Jenks Shipbuilding Company was founded in 1889, renamed in 1903 as Port Huron Shipbuilding and ceased operations sometime after 1908.[37] The shipyard was found on the north bank of the Black River between Erie Street and Quay Street which is now a parking area for Bowl O Drome and Port Huron Kayak Launch.

Ships built by Jenks include:

- SS Henry Steinbrenner - 1901 bulk freighter, lost in a storm on Lake Superior

- SS John B. Cowle - 1902 bulk freighter

- MS Normac - 1902 former fireboat and floating restaurant

- SS Eastland - 1902 passenger vessel, capsized in Chicago in the worst maritime disaster on the Great Lakes.

Steam Tractors

[edit]The Upton Manufacturing Company moved to Port Huron and began building steam tractors in 1890 under the name of the Port Huron Engine and Thresher Company. The company made steam traction engines, agricultural machinery, and even construction equipment. Over 6,000 total units were built in Port Huron before the factory closed in 1920.[38][39]

Gas and Oil

[edit]The discovery of oil in nearby Petrolia, Ontario sparked an era of oil speculation, and lead to Michigan's first commercial oil well being drilled in Port Huron in 1886. A total of 21 wells were drilled in the city by 1910, with "small amounts of oil and gas" discovered.[40] Though not much oil was produced in these wells, it did lead to further exploration throughout St. Clair County and Mid-Michigan.[41]

Paper making

[edit]There were two paper mills in Port Huron. The first was the Michigan Sulphite Fibre Company, later Port Huron Sulphite and Paper Company, which opened in 1888 and manufacturing paper clothing at a factory in along the Black River. The company later transitioned to more specialty types of paper, and was sold to the E. B. Eddy Company in 1987, which was acquired by Domtar in 1998. The mill specialized in papers for the medical and food service industries.[42]

Adjacent to the Domtar Mill is the site of the former Acheson Colloids Company. Dr. Edward Acheson in 1908 founded the company, which made a variety of chemical and carbon-based products.[43] The carbon manufactured by Acheson would be used to produce carbon paper at the adjacent Port Huron Paper Company, under the Huron Copysette brand.[44] The factory was purchased by Henkel and closed in 2010. However, Henkel continues to manufacture ink and carbon products using the Acheson name.[45]

Dunn Sulphite Paper Co. was erected upon the shores of Lake Huron in 1924, just north of the Blue Water Bridge. It too was a specialty paper mill and was owned by the Dunn Family of Port Huron for the first quarter-century of operation.[46] After a series of sales to larger corporations, including the James River Corporation, the mill was purchased by a private equity firm in 2003 which re-instated the Dunn name. The Dunn Paper mill closed in 2022,[47] and the remaining Dunn mills were renamed BiOrigin Specialty Products. [48]

Domtar closed the Port Huron mill in 2021.[49] It was announced in 2025 that the former Domtar Mill was sold and would restart production on one if its paper machines under the ownership of Legacy Paper Group.[50]

Cement

[edit]The Peerless Cement Company operated a cement plant just south of the Blue Water Bridge from 1924 to 1973. The waterfront site is now the location of the Edison Inn and Blue Water Convention Center.[51]

Automotive

[edit]The Havers Motor Car Company produced cars in Port Huron from 1911 until 1914 in buildings previously used by the Port Huron Engine and Thresher Company.

A variety of factories related to the automotive industry occupy Port Huron's Industrial Park on the city's south side. Many of these produce plastic components for vehicles.

Healthcare

[edit]Port Huron is served by two acute care facilities, McLaren Port Huron (formerly known as Port Huron Hospital), and Lake Huron Medical Center (formerly known as St. Joseph Mercy Hospital Port Huron).

McLaren Health Care Corporation, a nonprofit managed care health care organization based in Flint, purchased the former Port Huron Hospital and began operating the 186-bed facility as Mclaren Port Huron in May 2014.[52]

Lake Huron Medical Center, is a 144-bed facility operated by Ontario, California based Prime Healthcare Services. The for-profit company purchased the former St. Joseph Mercy Port Huron hospital in September 2015 from Trinity Healthcare.[53] Upon completion of the sale, the formerly non-profit Catholic institution converted to a for-profit entity.

Finance

[edit]CF Bancorp, a bank holding company for Citizens Federal Bank, was based in Port Huron. It was closed by regulators in April 2010 after it suffered from bank failure in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis.[54][55]

There are currently four banks with a total of seven branches in the city containing $563 million in deposits, which are, in order of local deposit market share: JPMorgan Chase (2 branches), Huntington Bancshares (3 branches), Eastern Michigan Bank (1 branch), and Northstar Bank (1 branch).[56]

Utilities

[edit]Port Huron's first utility was the Port Huron Gas Light Company, established on April 2, 1970. It was the first of its kind in the city, and one of the first public utilities in the State of Michigan. The "Gas Works" were located on River Street (Now Quay Street) near the 7th Street Bridge where gas was manufactured from coal. [57]

This was soon followed by the establishment of the Excelsior Electric Company in 1884. The company was the first in St. Clair County and one of the earliest in the United States. Electricity was generated at a power plant located on East Water Street near the mouth of the Black River. Both companies would later become absorbed into the Detroit Edison company.[58]

The gas business was later spun off into the Southeastern Michigan Gas Company in 1950.[59] Now known as SEMCO, the gas company is still headquartered in Port Huron and serves customers throughout The Thumb area of Michigan, in the Albion and Battle Creek areas of Southwest Michigan, and in some communities of the Upper Peninsula.[60]

Media

[edit]Radio

[edit]The first station to sign on in Port Huron was WAFD, which stood for We Are Ford Dealers.[61] The station was owned by the Albert B. Parfet Company, a local Ford car dealership. WAFD signed on March 4, 1925, and signed off in 1926, with plans to relocate the station to Detroit.[62]

WHLS, coinciding with the opening of the Blue Water Bridge, signed on in 1938. It was founded by Harold Leroy Stevens and Fred Knorr. John Wismer became part owner of the station in 1952. He would later launch the first cable television system in Port Huron and WSAQ in 1983. Wismer died in 1999. WHLS remains the longest continually operated station in the region.

The Times Herald launched its own radio station in 1947 known as WTTH. That station would later become WPHM, and was bought by Lee Hanson in 1986. WPHM got FM sister station WBTI in 1992. Wismer and Hanson were direct competitors until they were both bought by Bob Liggett's Radio First in 2000.

Radio First owns and operates five radio stations in the region while Port Huron Family Radio is the licensee of sole station WGRT. Non-commercial stations include WRSX (an affiliate of Michigan Public and NPR), high school station WORW, and religious broadcasters WNFA and WNFR.

Local FM[edit]

|

Local AM[edit]

|

Newspaper

[edit]- The Times Herald, a daily local newspaper serving St Clair County and Sanilac counties. It is owned by Gannett, which also owns the Detroit Free Press and USA Today.

- Daily editions of the Detroit Free Press and The Detroit News are also available throughout the area.

Broadcast television

[edit]St. Clair County lies in the Detroit television market. Channels available on Comcast are as follows:

Metro Detroit[edit] |

Southwestern Ontario[edit]

St. Clair County also receives the following stations from the Sarnia / London area, but are currently not carried on cable:

|

Transportation

[edit]

Major highways

[edit]Two Interstates terminate at the Port Huron-to-Sarnia Blue Water Bridge, and they meet Highway 402.

I-69 enters the area from the west, coming from Lansing and Flint, terminating at the approach to the Blue Water Bridge in Port Huron, along with I-94. On the Canadian side of the border, in Sarnia, Ontario, the route heads easterly designated as Highway 402. (Once fully completed, the mainline of I-69 will span from the U.S.–Mexico border in Brownsville, Texas, to the U.S.–Canada border in Port Huron, Michigan.)

I-69 enters the area from the west, coming from Lansing and Flint, terminating at the approach to the Blue Water Bridge in Port Huron, along with I-94. On the Canadian side of the border, in Sarnia, Ontario, the route heads easterly designated as Highway 402. (Once fully completed, the mainline of I-69 will span from the U.S.–Mexico border in Brownsville, Texas, to the U.S.–Canada border in Port Huron, Michigan.) I-94 enters the Port Huron area from the southwest, having traversed the entire Metro Detroit region, and, along with I-69, terminates at the approach to the Blue Water Bridge in Port Huron. On the Canadian side of the border, in Sarnia, Ontario, the route heads easterly designated as Highway 402.

I-94 enters the Port Huron area from the southwest, having traversed the entire Metro Detroit region, and, along with I-69, terminates at the approach to the Blue Water Bridge in Port Huron. On the Canadian side of the border, in Sarnia, Ontario, the route heads easterly designated as Highway 402. BL I-69

BL I-69 BL I-94

BL I-94 M-25 follows the Lake Huron/Saginaw Bay shoreline, beginning in Bay City and ending in at junction with I-94/I-69, and BL I-94/BL I-69 on the north side of the city.

M-25 follows the Lake Huron/Saginaw Bay shoreline, beginning in Bay City and ending in at junction with I-94/I-69, and BL I-94/BL I-69 on the north side of the city. M-29 begins at BL I-94 in Marysville just south of the city and continues southerly.

M-29 begins at BL I-94 in Marysville just south of the city and continues southerly. M-136 runs west from M-25 to M-19.

M-136 runs west from M-25 to M-19.

Mass transit

[edit]The Blue Water Area Transit system,[63] created in 1976, includes eight routes in the Port Huron area. Blue Water Transit operates the Blue Water Trolley, which provides a one-hour tour of various local points of interest. Recently, Blue Water Area Transit received a grant from the state to buy new buses for a route between the Port Huron hub and New Baltimore about 30 miles (48 km) south. Commuters could take an express bus traveling down I-94 and get off at the 23 Mile Road SMART Bus stop. At the same time, another bus will travel down M-25 and M-29 and pick up commuters in Marysville, Saint Clair and Algonac before ending up at the same stop on 23 Mile Road. This new system will help people in St. Clair County travel through Metro Detroit.

Rail

[edit]- Amtrak provides intercity passenger rail service on the Blue Water route from Chicago to Port Huron (Amtrak station).

- Two class one freight railroads operate in Port Huron – Canadian National Railway (CN) and CSX Transportation (CSXT) with international connections via the St. Clair Tunnel.

- Via Rail train service from Toronto to Sarnia (part of the Quebec City–Windsor Corridor) is also available; however, this train does not cross the river, requiring passengers to make arrangements for road travel to Port Huron.

Airports

[edit]St. Clair County International Airport is a public airport located five miles (8 km) southwest of the central business district.

Notable people

[edit]- Edward Goodrich Acheson (1856–1931), inventor of carborundum

- Emma Eliza Bower (1852–1937) physician, club-woman, and newspaper owner, publisher, editor

- Burt D. Cady, politician

- Jack Campbell, hockey player

- Ezra C. Carleton, mayor and congressman

- Robert Hardy Cleland, judge

- Omar D. Conger, senator for Michigan

- Deepchord, electronic music producer

- Thomas Edison (1847–1931), inventor and entrepreneur, moved to Port Huron in 1854

- Elizabeth Farrand, author and librarian

- Shawn Faulkner, football player

- Eugene Fechet, army officer

- Otto Fetting, religious leader

- Obadiah Gardner, senator for Maine

- Jim Gosger, baseball player

- Dorothy Henry, illustrator, cartoonist, painter

- Bill Hogg, baseball pitcher

- Herbert W. Kalmbach, attorney for President Richard Nixon

- Fred Lamlein, baseball player

- Michael Mallory, author

- Steve Mazur, guitarist

- William McColl, clarinetist[64]

- Robert J. McIntosh, politician and pilot

- Terry McMillan, author

- Henry McMorran, businessman and congressman

- Marko Mitchell, football wide receiver

- Colleen Moore, silent movie era actress

- John Morrow, football center

- Jason Motte, baseball pitcher

- Robert C. Odle Jr., lawyer

- Clifford Patrick O'Sullivan, judge

- Dick Van Raaphorst, football placekicker

- Kevin Rivers, tech businessman and songwriter

- Mary Alma Ryan, Catholic nun and superior of the school that became Saint Mary-of-the-Woods College.

- Frank Secory, baseball player and umpire

- Frederick C. Sherman, admiral

- Annah May Soule (1859–1905), professor at Mount Holyoke College

- Nina Spalding Stevens (1876–1959), museum director

- Sara Stokes, singer

- Dennis Sullivan, mathematician

- John Swainson (1925–1994), Governor of Michigan and a Justice of the Michigan Supreme Court

- Stephan Thernstrom, professor and author

- Harold Sines Vance, businessman and government official

- Kris Vernarsky, hockey player

- Felix Watts, inventor

- Harry Wismer, broadcaster and sports team owner

- James Kamsickas, businessman

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 21, 2022.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Port Huron, Michigan

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on May 31, 2011. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ^ Helen Hornbeck Tanner. Atlas of Great Lakes Indian History. (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1987) p. 165

- ^ "Population of Port Huron" Archived April 2, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, East Saginaw Courier, October 13, 1859, View 2, Chronicling America, Library of Congress, accessed September 5, 2014

- ^ "History of St. Clair County - Port Huron Township & City". ancestry.com. Archived from the original on November 11, 2009. Retrieved November 10, 2009.

- ^ Walter Romig, Michigan Place Names, p. 204

- ^ "Historical marker to commemorate political manifesto". WPHM.

- ^ Shepard, Liz (April 30, 2018). "Port Huron's past included on lynching memorial". ort Huron Times Herald. Retrieved March 18, 2018.

- ^ "Veterans Day 2017: Honoring sacrifices of veterans who serve us". November 11, 2017. Archived from the original on April 29, 2023.

- ^ "Veterans Day is about honoring those who sacrifice for country". The Times Herald. November 11, 2017.

- ^ "Train bridge demolition wraps up".

- ^ "Port Huron Railroad Bridge (Pere Marquette Railroad Bridge) - HistoricBridges.org". historicbridges.org.

- ^ "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 20, 2011. Retrieved November 25, 2012.

- ^ "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on June 5, 2021. Retrieved May 4, 2021.

- ^ "Summary of Monthly Normals 1991–2020". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on May 4, 2021. Retrieved May 4, 2021.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved November 25, 2012.

- ^ "Home". November 2, 2024.

- ^ "Carnegie Center, Port Huron Museum".

- ^ "The Dude, The Port Huron Statement, and The Seattle Seven". mentalfloss.com. January 10, 2011. Archived from the original on June 15, 2018. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- ^ Smith, Jackie (January 1, 2024). "Spot Port Huron references in these popular films and TV episodes". The Times Herald.

- ^ "Radio man gives back to the community". thetimesherald.com. Retrieved March 18, 2018.

- ^ Gibbons, Lauren (August 16, 2017). "Michigan State University, city of East Lansing at odds over proposed income tax". MLive Lansing. Mlive Media Group. Archived from the original on August 16, 2017. Retrieved August 16, 2017.

- ^ "Port Huron elects new mayor and council member | WPHM". www.wphm.net. Retrieved August 5, 2025.

- ^ "Port Huron considers allowing residents to raise backyard chickens for sustainability". Citizen Portal. Retrieved May 23, 2025.

- ^ "Ordinance amendment is introduced to allow the raising of chickens in Port Huron". Blue Water Healthy Living. Retrieved May 23, 2025.

- ^ "DeSana introduces legislation to allow backyard chickens". MI House Republicans. Retrieved May 23, 2025.

- ^ https://phahpa.org/2016/08/12/st-clair-county-during-the-territorial-period-1805-1837/

- ^ "Grain Elevator at Port Huron, St. Clair River". dia.org.

- ^ "History". Archived from the original on June 15, 2018. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- ^ Connell, Michael (December 6, 2014). "Memory of roasting chicory lingers". The Times Herald.

- ^ Connell, Michael (October 18, 2014). "Port Huron once dominated chicory trade". The Times Herald.

- ^ "Mueller Co. Locations – Mueller Museum". Archived from the original on June 15, 2018. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- ^ "Mueller Industries - Aluminum forging and brass and lead - free brass forging - Markets Served - Forgings". muellerindustriesipd.com. Archived from the original on June 15, 2018. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- ^ "Jenks Ship Building".

- ^ "Port Huron steam engine saved from scrap pile". Archived from the original on January 25, 2025. Retrieved November 17, 2025.

- ^ "Port Huron Engine & Thresher Co. - History | VintageMachinery.org". vintagemachinery.org. Retrieved November 17, 2025.

- ^ "History of Michigan's Oil and Natural Gas Industry | Clarke Historical Library". Central Michigan University. Retrieved November 17, 2025.

- ^ https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=136472

- ^ "Port Huron Mill - Domtar". Domtar.com. Archived from the original on June 15, 2018. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- ^ "History". Archived from the original on June 15, 2018. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- ^ "Assignment Center". assignmentcenter.uspto.gov. Retrieved November 17, 2025.

- ^ "BONDERITE®". next.henkel-adhesives.com.

- ^ Donnelly, Francis X. "'It gave us a good life': Port Huron mourns the passing of its papermaking era". The Detroit News. Retrieved November 17, 2025.

- ^ "Port Huron paper mill to close in November".

- ^ https://www.bioriginsp.com/

- ^ "'I will miss my mill': Officials, employees reflect on Domtar Corp. Closing Port Huron mill".

- ^ "Paper production returning to Port Huron | WPHM". www.wphm.net. Retrieved August 5, 2025.

- ^ Gaffney, T. J. (2006). Port Huron, 1880-1960. Arcadia Publishing. pp. 50–. ISBN 978-0-7385-4119-8.

- ^ "Port Huron Hospital becomes McLaren's 12th hospital". crainsdetroit.com. May 1, 2014. Archived from the original on March 19, 2018. Retrieved March 18, 2018.

- ^ "Public forum set on sale of St. Joseph Mercy Port Huron to for-profit chain". Crain Communications. March 31, 2015. Archived from the original on September 28, 2015.

- ^ "Failed Bank Information for CF Bancorp, Port Huron, MI". Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation.

- ^ "Feds close Citizens First Bank". Huron Daily Tribune. May 3, 2010. Archived from the original on June 24, 2018.

- ^ "Deposit Market Share Reports - Summary of Deposits". Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation.

- ^ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b9-SPUO8vlU

- ^ Mitts, Dorothy (1958). A History of Gas Service in Port Huron. Jensen-Townsend printing company. p. 131.

- ^ https://www.albionmich.com/history/histor_notebook/070422.shtml

- ^ https://www.semcoenergygas.com/company-description/#:~:text=SEMCO%20ENERGY%20Gas%20Company%2C%20headquartered,around%20the%20cities%20of%20Albion%2C

- ^ "The Radio Lighthouse" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on May 1, 2023.

- ^ "Radio service bulletin" (PDF). January 31, 1927.

- ^ "Blue Water Area Transit". bwbus.com. Archived from the original on December 6, 2006. Retrieved December 14, 2006.

- ^ "William McColl Obituary". Seattle Times. January 17, 2024. Retrieved January 30, 2024.

External links

[edit]Surrounding communities

[edit]Port Huron, Michigan

View on GrokipediaPort Huron is a city and the county seat of St. Clair County in the U.S. state of Michigan, extending seven miles along the St. Clair River at its outlet into Lake Huron and serving as a primary international border crossing to Point Edward and Sarnia, Ontario, Canada, via the Blue Water Bridge.[1][2][3] The city's population was estimated at 28,342 residents as of July 2024.[4] Positioned as a maritime gateway to Michigan's Thumb region, Port Huron has long been central to Great Lakes shipping and trade, while also gaining prominence as the starting point for the annual Bayview Mackinac sailing race, which began in 1925 and stands as one of the world's longest freshwater yacht races.[5]

History

Early settlement and founding (pre-1850s)

The territory encompassing present-day Port Huron was historically occupied by the Chippewa (Ojibwe) tribe, who exploited the site's strategic position at the confluence of the St. Clair River and Lake Huron for seasonal fishing, hunting, and as part of broader trade networks across the Great Lakes region prior to European contact.[6] Early European exploration in the area was limited, with French traders and missionaries active in the broader St. Clair region during the 17th and 18th centuries, but no permanent non-Native settlements were established before the late 1700s. The initial European-American presence began with Denis Causley (also recorded as Causlet), a fur trader of likely French-Canadian descent, who settled near the mouth of the Black River around 1780–1790, marking the earliest known permanent non-Native habitation in the vicinity.[7] In 1807, a reservation for the Chippewa was formally platted on the south side of the Black River, reflecting ongoing Native land use amid encroaching settler interests.[8] Families such as the Petits, including Anselm Petit and his descendants, emerged as early permanent residents in the early 19th century, with structures from this period enduring into later years.[9] A pivotal development occurred in 1814 when the United States Army constructed Fort Gratiot to secure the critical waterway junction against potential British and Native American threats in the aftermath of the War of 1812.[10][8] Named for Lieutenant Colonel Charles Gratiot, the fort's garrison of soldiers from diverse regions provided the nucleus for civilian settlement, as many discharged troops opted to remain, farming and trading in the area. This military outpost facilitated the transition from transient Native and fur trade activities to organized Euro-American community formation, though the population remained sparse, numbering fewer than a hundred by the 1820s.[11]Industrial expansion and maritime growth (1850s-early 1900s)

Port Huron's population expanded significantly during the mid-to-late 19th century, rising from 1,584 in 1850 to 4,371 in 1860 and 5,977 in 1870, fueled by its strategic position at the St. Clair River's outlet into Lake Huron.[12] This growth incorporated the village into a city in 1857 and positioned it as a vital hub for lumber processing and export, with four new sawmills constructed in the 1850s alone.[12] The surrounding St. Clair County's abundant pine forests—white, juniper, hemlock, and spruce—supplied the industry, which shipped vast quantities via lake vessels to eastern markets.[13] Lumber dominated early industrial activity, establishing Port Huron as one of Michigan's premier manufacturing points for the commodity by the 1860s, though depletion led to decline by the 1870s.[12] Shipbuilding emerged alongside, with approximately 60 vessels constructed in the 1860s to support maritime transport of timber and goods across the Great Lakes.[12] By the late 1880s, firms like Jenks Shipbuilding (founded 1889) advanced into steel hulls, contributing to Port Huron's ranking as a secondary shipbuilding center after Marine City by the early 1900s.[13] Railroad integration amplified maritime and industrial synergies, with the Grand Trunk Railway linking Port Huron to Detroit in 1859 and extending to Sarnia, Ontario, via car ferries.[13] The pivotal St. Clair Tunnel, completed in 1891 as North America's first full-scale subaqueous railroad tunnel, enabled seamless cross-border freight movement under the river, sustaining trade volumes despite lumber's wane.[14] This infrastructure spurred further population gains to 13,543 by 1890 and 19,158 by 1900, incorporating adjacent Fort Gratiot lands and diversifying into manufacturing like agricultural engines.[12]Mid-20th-century developments and challenges (1900s-1970s)

The construction and opening of the Blue Water Bridge in 1938 marked a significant infrastructural advancement for Port Huron, establishing the first vehicular international crossing over the St. Clair River to Sarnia, Ontario. Funded jointly by the United States and Canada at a cost of $4 million, the three-lane cantilever bridge replaced reliance on ferries and rail tunnels, thereby boosting cross-border trade, tourism, and economic connectivity during the late Depression era and into World War II.[15][16] Maritime commerce along the St. Clair River continued to underpin the local economy, with Port Huron functioning as a critical hub for Great Lakes freighters transporting bulk cargoes such as grain and agricultural products. By the late 1960s and early 1970s, the port specialized in navy bean exports, earning the designation "Bean Port" within the shipping industry and servicing dozens of vessels annually at facilities like the Seaway Terminal.[17] This reliance on waterborne trade sustained employment in docking, warehousing, and related sectors, though it exposed the city to fluctuations in global commodity prices and seasonal navigation constraints imposed by ice on Lake Huron and the river.[17] Urban renewal initiatives from the 1960s onward presented challenges to Port Huron's built environment, leading to the demolition of numerous historic buildings, including the 1891 Grand Trunk Western railroad depot in 1975, which left vacant lots and eroded architectural heritage without commensurate economic gains.[18][19] Concurrently, civic investments addressed post-war community demands, such as the development of Memorial Recreation Park and the construction of Mercy Hospital expansions, reflecting efforts to modernize amid national trends of suburbanization and industrial maturation.[20] These projects, while enhancing public amenities, strained municipal budgets and highlighted tensions between preservation and progress in a city transitioning from lumber and rail dominance to diversified manufacturing and port operations.[20]Late 20th and 21st-century transitions (1980s-present)

During the 1980s, Port Huron faced significant economic pressures amid Michigan's manufacturing recession, which saw statewide job losses exceeding 300,000 in the auto sector between 1979 and 1982, with ripple effects in dependent communities like Port Huron through reduced supply chain and ancillary employment.[21][22] Local industries, tied to Great Lakes shipping and automotive parts, contributed to a pattern of stagnation, as St. Clair County's growth lagged national trends post-1990, with manufacturing employment contracting amid globalization and automation.[23] The city's population, which stood at approximately 33,981 in 1980, began a steady decline reflective of these shifts, dropping to 32,338 by 2000—a 4.9% loss—driven by out-migration to suburbs and limited new job creation.[24][25] Infrastructure enhancements marked key adaptations, including the completion of the second St. Clair River rail tunnel in 1994, designed for double-stack intermodal containers to boost cross-border freight efficiency and sustain trade volumes exceeding traditional limits.[26] The Blue Water Bridge, handling over 4 million vehicles annually by the 2000s, underwent plaza expansions starting in the 1990s and accelerating in the 2020s, with Michigan Department of Transportation projects relocating ramps and adding lanes on I-94 to alleviate congestion and support commercial traffic to Canada.[27][28] These developments aimed to leverage the city's border position, yet economic metrics remained challenged, with median household income at $47,906 in 2022 and unemployment at 5.9% in 2025, amid ongoing manufacturing erosion.[29] Revitalization initiatives in the late 20th and early 21st centuries focused on waterfront and downtown renewal, including the 2007 opening of the $9 million Blue Water Convention Center for events and meetings, alongside 70-acre Black River redevelopment incorporating maritime centers and public amenities to attract tourism and stabilize employment.[30][31] Private investments, such as $6 million renovations to historic Huron Avenue buildings in 2014, complemented public efforts, though population continued to fall to 28,974 by 2020 and further to an estimated 28,724 by 2023, attributed to suburban flight, aging infrastructure overcapacity, and insufficient high-wage opportunities beyond seasonal or trade-dependent roles.[32][33][4] Recent projects, including the 2023 demolition of the outdated Pere Marquette rail bridge and ongoing bridge plaza work, signal continued emphasis on logistics resilience, but broader socioeconomic indicators point to persistent transitions without full recovery.[34]Geography

Location, topography, and boundaries

Port Huron serves as the county seat of St. Clair County in southeastern Michigan, positioned at the easternmost point of the state's Lower Peninsula. The city lies at the southern terminus of Lake Huron, where the St. Clair River originates and flows southward, forming the initial segment of the waterway connecting Lake Huron to Lake Erie. Its geographic coordinates are 42°58′15″N 82°25′29″W.[35] Directly adjacent to the Canada–United States border, Port Huron faces Sarnia, Ontario, across the St. Clair River, facilitating cross-border commerce via bridges and tunnels. The municipal boundaries enclose waterfront along Lake Huron to the north and the St. Clair River to the east, adjoining Port Huron Charter Township to the west and south.[36][37] The topography features a relatively flat glacial plain with minimal relief, averaging 607 feet (185 meters) in elevation above sea level. Bedrock formations exhibit flat-lying strata with subtle undulations and a gentle eastward dip toward the St. Clair River, influencing local drainage patterns.[35][38] As measured by the U.S. Census Bureau, the city spans a land area of 8.10 square miles (20.98 km²) in 2020, reflecting compact urban development concentrated along the waterfront.Climate and environmental features

Port Huron has a humid continental climate (Köppen Dfa), with cold, snowy winters, warm summers, and significant precipitation throughout the year influenced by its location on the St. Clair River at the outlet of Lake Huron. The lake moderates extreme temperatures but enhances snowfall through lake-effect events, particularly from November to March, while prevailing westerly winds contribute to variable weather patterns. Annual average temperatures range from about 20°F (–7°C) in January to 75°F (24°C) in July, with an overall yearly mean of approximately 48°F (9°C).[39][40][41] Precipitation totals average 35 inches (890 mm) annually, distributed across 134 days, including about 35–37 inches (89–94 cm) of snowfall, exceeding the U.S. average due to Great Lakes effects. Summer months see the highest rainfall, often from thunderstorms, while winter precipitation is roughly half snow. Extreme events include record highs near 105°F (41°C) and lows around –20°F (–29°C), with historical floods from St. Clair River overflows, such as in 1986 when water levels rose over 2 feet above normal, impacting low-lying areas. Recent data from 1951–2024 indicate a 16.5% increase in annual precipitation, attributed to warmer atmospheric moisture capacity, though temperature trends show modest warming of about 1–2°F.[40][42][41]| Month | Avg High (°F) | Avg Low (°F) | Precip (in) | Snow (in) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| January | 30 | 17 | 1.9 | 10.7 |

| July | 80 | 60 | 3.3 | 0 |

| Annual | 57 | 39 | 34.9 | 35.0 |

Demographics

Population trends and census data

The population of Port Huron grew steadily through the mid-20th century, driven by industrial expansion and maritime activity, reaching a peak of 35,829 residents in the 1970 census.[24] Thereafter, the city experienced consistent decline, with decennial census figures showing losses attributed to outmigration amid deindustrialization in the Great Lakes region, where manufacturing employment contracted significantly from the 1970s onward.[4] By the 2020 census, the population had fallen to 28,983, a reduction of about 19% from the 1970 peak.[4]| Census Year | Population | Percent Change from Previous Decade |

|---|---|---|

| 1970 | 35,829 | - |

| 1980 | 33,981 | -5.2% |

| 1990 | 33,701 | -0.8% |

| 2000 | 32,338 | -4.0% |

| 2010 | 30,184 | -6.7% |

| 2020 | 28,983 | -4.0% |

Ethnic, income, and socioeconomic profiles

As of the latest American Community Survey estimates for 2023, Port Huron's population of 28,724 is predominantly White non-Hispanic, comprising 78.5% of residents, reflecting historical patterns of settlement by European immigrants in the region's industrial era.[29] Black or African American non-Hispanic residents account for 6.79%, two or more races (non-Hispanic) for 5.98%, and Hispanic or Latino residents of any race for 7.1%, with smaller shares including Asian (under 1%) and American Indian/Alaska Native (around 0.4%).[29] [48] These figures align closely with the 2020 Decennial Census, which reported 77.5% White alone, 8.0% Black alone, and 5.8% Hispanic or Latino, indicating relative stability in ethnic composition amid gradual diversification driven by migration and birth rates.[49]| Race/Ethnicity (2023 ACS) | Percentage of Population |

|---|---|

| White (Non-Hispanic) | 78.5% |

| Black or African American (Non-Hispanic) | 6.79% |

| Two or More Races (Non-Hispanic) | 5.98% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 7.1% |

| Other groups (Asian, Native American, etc.) | ~1.6% |

Government and politics

Municipal structure and administration

Port Huron operates under a council-manager form of government, featuring an elected city council for policy-making and a professionally appointed city manager for administrative execution.[52] [53] This structure, codified in the city charter approved by voters on November 2, 2010, and effective January 1, 2011, emphasizes separation between legislative oversight and operational management to promote efficiency and accountability.[53] The City Council consists of seven members: a mayor and six at-large council members, all elected in nonpartisan contests.[52] The mayor holds a two-year term, while council seats feature four-year staggered terms to ensure continuity, with elections occurring during even-year November general elections.[52] As of October 2025, Mayor Anita Ashford's term concludes in November 2026; council members include Sherry Archibald (mayor pro tem, term ends November 2028), Conrad Haremza (November 2026), Teri Lamb (November 2028), Bob Mosurak (November 2026), Barbara Payton (November 2028), and Jeff Pemberton (November 2026).[52] The council enacts ordinances, establishes fiscal policies, and appoints the city manager, but does not directly manage daily affairs.[52] The city manager, James R. Freed as of 2025, functions as chief administrative officer under council direction, overseeing department operations, budget preparation, capital projects, and policy implementation.[54] Responsibilities include supervising professional staff, providing analytical recommendations to the council, enforcing municipal laws, and addressing service delivery to maintain operational transparency and responsiveness.[54] This setup delegates executive functions to the manager to leverage expertise while reserving strategic decisions for elected officials.[53]Political history, voting patterns, and policy debates

Port Huron's local elections are non-partisan, with the city governed by a mayor and city council elected at-large.[55] Historical records indicate a succession of mayors dating back to the late 19th century, including figures like Robert E. French in 1889 and Ezra Child Carleton, who served in 1881-1882 before his election to Congress as a Democrat.[56] [57] In recent decades, the city has seen longer tenures, such as Pauline Repp, who held the mayor's office until her defeat in the November 5, 2024, general election by Anita R. Ashford, a city council member and the first African-American mayor in Port Huron's history, with Ashford receiving 6,005 votes to Repp's 4,965.[58] [59] [60] St. Clair County, encompassing Port Huron, exhibits voting patterns that lean Republican in presidential elections, supporting the GOP candidate in five of the six contests from 2000 to 2020, with the exception of 2008 when Barack Obama prevailed.[61] This aligns with broader trends in Michigan's Thumb region, though St. Clair has occasionally mirrored national swings, such as narrower Republican margins in competitive cycles like 2020.[62] [63] Local races, lacking party labels, reflect community priorities like economic revitalization amid industrial decline, but voter turnout and outcomes often correlate with county-wide conservative inclinations.[64] Policy debates in Port Huron have centered on administrative governance, public health, and fiscal resource allocation. A prominent controversy involves tensions between Mayor Ashford and City Manager James Freed, escalating in 2025 with public accusations of mismanagement and a city council vote for Freed's performance review amid claims it distracts from core issues like infrastructure and economic development.[65] [66] Freed's prior role drew national attention in Lindke v. Freed (2024), a U.S. Supreme Court case originating from his blocking of a constituent on social media, which ruled that officials acting in official capacities cannot censor viewpoints on personal accounts used for public business.[67] In public health, debates over water fluoridation led Port Huron officials in 2025 to consider discontinuation, redirecting funds to alternative dental programs amid community concerns over efficacy and costs.[68] Broader county-level discussions, influencing city policy, include health service funding and board appointments, with commissioners reprimanding appointees for inflammatory remarks in October 2025.[69] [70] These issues underscore tensions between fiscal conservatism, administrative accountability, and public service delivery in a border community facing economic pressures.Economy

Sector overview and employment data

Port Huron's employed resident population totaled 12,581 in 2023, up 0.56% from 12,500 in 2022.[29] The city's labor force participation aligns with regional trends, though specific city-level metrics reflect broader St. Clair County dynamics, where the labor force reached 80,535 in recent quarterly data.[71] Key employment sectors for Port Huron residents, drawn from American Community Survey data, emphasize manufacturing and services, as shown below:| Sector | Employed Residents |

|---|---|

| Manufacturing | 2,497 |

| Health Care & Social Assistance | 2,316 |

| Retail Trade | 1,633 |

.jpg/250px-Port_Huron_(March_2019).jpg)

.jpg/2000px-Port_Huron_(March_2019).jpg)