Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

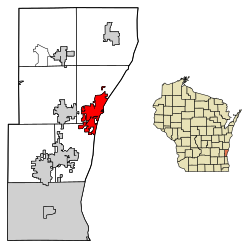

Port Washington, Wisconsin

View on Wikipedia

Port Washington is a city in Ozaukee County, Wisconsin, United States, and its county seat. Located on Lake Michigan's western shore east of Interstate 43, the community is a suburb in the Milwaukee metropolitan area 27 miles (43 km) north of Milwaukee. The city's artificial harbor at the mouth of Sauk Creek was dredged in the 1870s and was a commercial port until the early 2000s. The population was 12,353 at the 2020 census.

Key Information

When French explorers arrived in the area in the 17th century, they found a Native American village at the mouth of Sauk Creek—the present location of historic downtown Port Washington. The United States Federal Government forcibly expelled the Native Americans in the 1830s, and the first settlers arrived in 1835, calling their settlement "Wisconsin City" before renaming it "Port Washington" in honor of President George Washington.[4] In the late 1840s and early 1850s, the community was a candidate to be the Washington County seat. Disagreements between municipalities and election fraud prevented Washington County from having a permanent seat of government until the Wisconsin State Legislature intervened, creating Ozaukee County out of the eastern third of Washington County and making Port Washington the seat of the new county.

For much of its history, Port Washington has been tied to the Great Lakes. Early settlers used boats to transport goods including lumber, fish, and grains, although the community's early years were marred by shipwrecks, which led the U.S. Federal Government to construct Port Washington Harbor in 1871. Commercial fishing prospered in Port Washington until the mid-20th century, and beginning in the 1930s, the Port Washington Generating Station used the harbor to receive large shipments of coal to burn for electricity. The commercial harbor closed in 2004 when the power station switched to natural gas for fuel, but the community maintains an active marina for recreational boaters. In the 21st century, Port Washington celebrates its lacustrine heritage with museums, public fish fries, sport fishing derbies, and sailboat races.

History

[edit]Early history and settlement

[edit]

The area that became Port Washington was originally inhabited by the Menominee, Potawatomi, and Sauk Native Americans. In 1679, the French explorers Louis Hennepin and René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle described stopping at the first landing north of the Milwaukee River to procure provisions at a Potawatomi village at the mouth of a small river, which may have been Sauk Creek, a stream that empties into the present-day Port Washington's artificial harbor.[5]

The 1830s saw the forced removal of Wisconsin's Native American population, followed by land speculation by merchants and investors. One of these land speculators was General Wooster Harrison, who purchased the land that would become Port Washington in 1835, which he originally named "Wisconsin City."[6][7] Harrison's wife, Rhoda, died in 1837 and was the first white settler to be buried in the town.[8] The settlement was abandoned that same year.

In 1843, Harrison returned with a party of settlers. The Town of Port Washington was formed in January 1846 and until 1847 included the surrounding areas of Fredonia, Saukville, and Belgium.[9] At the time, the land was part of Washington County, and in the late 1840s, Port Washington was a candidate for the county seat. However, the community was far from the county's other early settlements, including Mequon, Grafton and Germantown. In 1850, the Wisconsin legislature voted to bisect Washington County into northern and southern counties, with Port Washington and Cedarburg as the respective county seats. County residents failed to ratify the bill, and in 1853, the legislature instead bisected the county into eastern and western sections, creating Ozaukee County. Port Washington became the seat of the new county, and the Washington County seat moved to West Bend.[10] The bisection was controversial. When Washington County officials from West Bend arrived in Port Washington to correct relevant county records, they were run out of town, and Ozaukee County officials refused to hand over the records for several months.[11]

19th century growth and industrialization

[edit]

The early settlers saw potential in the community's lakeside location and built piers to make their city into a port on Lake Michigan. The city exported cord wood, wheat and rye flour, bricks, fish, and hides, among other things.[12] However, Port Washington did not have a natural harbor and its first decades were marred by shipwrecks, including the 1856 Toledo disaster, in which between 30 and 80 people died.[13]

In 1843, the first Christian religious services were held by the Methodist Episcopal Church in private homes. The first Catholic Church services were held in a similar manner in 1847.[14] The Washington Democrat, the town's first newspaper, was started in 1847 by Flavius J. Mills.[15]

The population reached 2,500 in 1853 and continued to increase, with an influx of immigrants from Germany and Luxembourg between 1853 and 1865.[16] When the American Civil War started, some of these immigrants found themselves in opposition to the federal government. The United States Congress implemented the draft in 1862, and Port Washington's immigrants, particularly those from Prussia and Luxembourg, were unpleasantly reminded of mandatory conscription in the countries they had left behind.[17] On November 10, 1862, several hundred Port Washington residents marched on the courthouse, attacked the official in charge of implementing the draft, burned draft records, and vandalized the homes of Union supporters. The riot ended when eight detachments of Union troops from Milwaukee were deployed.[18]

The early 1870s saw improvements to the community's transportation infrastructure. In 1870, Port Washington became a stop on the Lake Shore Railroad, which was later incorporated into the Chicago and North Western Railway.[19] In response to the numerous shipwrecks in the area, local officials also petitioned the federal government for assistance to dredge and create an artificial harbor. When the project was completed in 1871,[5] the harbor was a channel 14 feet (4.3 meters) deep and 1,500 feet (460 meters) long in which ships could dock to unload as well as shelter during storms.[20]

The City of Port Washington was incorporated in 1882. In the 1880s and 1890s, a large number of French and Belgian immigrants arrived in Port Washington.[21] Between 1900 and 1910, two relatively large groups of English immigrants also arrived in Port Washington. One group came directly from England and the other group had previously been residents of Canada.[22]

The last years of the 19th century saw Port Washington's economy become more industrial. In September 1888, J. M. Bostwick opened the Wisconsin Chair Company in the city. At its height, the company employed 30% of the county's population and accounted for roughly half of Port Washington's jobs. Between 1890 and 1900, Port Washington's population nearly doubled due to the company's success.[23] Additionally, the Bolens tractor company built its main factory in the city in 1894, and in 1896, Delos and Herbert Smith brought their commercial fishing business to Port Washington. The Smith Bros. company grew to a fleet of gillnetting fishing tugs, and they sold fish, whitefish caviar, and burbot oil in addition to operating restaurants and a hotel.[24]

On February 19, 1899, the Wisconsin Chair Company's factory caught fire. The building was destroyed and the conflagration spread, burning nearly half of Port Washington.[25] The damages were covered by fire insurance, and the company built an even bigger factory on the waterfront with direct rail access.[26]

20th century industrial decline and suburbanization

[edit]In the early 20th Century, the Wisconsin Chair Company opened additional factories in neighboring communities and bought tracts of forest in Green Bay, Chambers Island, Harbor Springs, Michigan, and the Upper Peninsula of Michigan to supply wood.[23] During the Panic of 1907 when there were currency shortages, the company's checks were treated as an informal currency in the community.[27] Among its products, the company manufactured phonographs for Thomas Edison. In an effort to boost sales, the company also started its Paramount Records subsidiary, which was one of the first record labels devoted to African-American music. Paramount operated in neighboring Grafton until it closed in 1935 during the Great Depression. The Wisconsin Chair Company closed in 1954.[5]

In November 1907, Port Washington became a stop on the Milwaukee-Northern interurban passenger line, and a power station on the lakefront provided electricity for the trains.[28] The community was the halfway point between Milwaukee and the line's northern terminus in Sheboygan. In the 1920s, The Milwaukee Electric Railway and Light Company purchased the line and continued to operate it until March 28, 1948, when the Ozaukee County line declined due to increased use of personal automobiles and better roads.[29]

Wisconsin Electric Power Company, now known as We Energies, built the Port Washington power plant in 1931. The project included an expansion of Port Washington's harbor and the construction of a large coal dock to accommodate the daily coal shipments the station received.[16]

The mid-20th century saw a decline in commercial fishing on the Great Lakes. Populations of fish including herring, lake trout, lake whitefish, and yellow perch declined due to decades of overfishing, pollution, and the arrival of invasive species, such as the alewife, the parasitic sea lamprey, and the zebra mussel.[30][31] The Smith Bros. fishing company closed in 1988,[32] and when the Port Washington power station took its coal-fired boilers out of service in 2004 and converted to natural gas, Port Washington's harbor closed as a commercial port.[5]

Despite the decline of decades-old industries, Port Washington experienced significant population growth during the suburbanization that followed World War II. Between 1940 and 1970, the population more than doubled, from 4,046 to 8,752, and the City of Port Washington annexed rural land from the surrounding Town of Port Washington and Town of Grafton for residential subdivisions. The construction of Interstate 43 west of Port Washington in the mid-1960s connected the city to neighboring communities and allowed more residents to commute for work.[11]

On August 22, 1964, an F4 tornado touched down in Port Washington, totally destroying twenty houses and causing severe damage to thirty-four others in a newly constructed subdivision. No one died, but thirty people were reported to have been injured.[33] There were approximately $2 million in damages,[34] which would have been over $16 million as of November 2019, if adjusted for inflation.[35]

Geography

[edit]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 7.08 square miles (18.34 km2), of which 5.82 square miles (15.07 km2) is land and 1.26 square miles (3.26 km2) is water.[36] The city is bordered by the Town of Port Washington to the north and west, the Town of Grafton to the south, and Lake Michigan to the east.

The city is located on the western shore of Lake Michigan. In northern and southern parts of the city, the coastline is characterized by clay bluffs ranging from 80 feet (24 meters) to 130 feet (40 meters) in height with deep ravines where streams flow into the lake. Clay bluffs are a geological formation characteristic of the Lake Michigan shoreline, and are found in few other areas of the world. Much of the coastline adjacent to the bluffs has mixed gravel and sand beaches. Port Washington's historic downtown in the central part of the city is in the Sauk Creek valley, at a lower elevation than the rest of the city.[37][38] The valley is a break in the bluffs, providing easy access to the lakeshore, which attracted early settlers to the area. Port Washington's artificial harbor, dredged in 1871 with subsequently constructed breakwaters, is located at the mouth of Sauk Creek, adjacent to downtown.[5]

The city is located in the Southeastern Wisconsin glacial till plains that were created by the Wisconsin glaciation during the most recent ice age. The soil is clayey glacial till with a thin layer of loess on the surface. The Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources considers the city to be in the Central Lake Michigan Coastal ecological landscape.[37]

As land development continues to reduce wild areas, wildlife is forced into closer proximity with human communities like Grafton. Large mammals, including white-tailed deer, coyotes, and red foxes can be seen in the city.[39] There have been infrequent sightings of black bears in Ozaukee County communities, including a 2010 sighting of a bear in a Port Washington residential neighborhood.[40]

The region struggles with many invasive species, including the emerald ash borer, common carp, reed canary grass, the common reed, purple loosestrife, garlic mustard, Eurasian buckthorns, and honeysuckles.[38]

Climate

[edit]| Climate data for Port Washington, Wisconsin (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1893–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 59 (15) |

63 (17) |

82 (28) |

92 (33) |

95 (35) |

102 (39) |

106 (41) |

103 (39) |

100 (38) |

89 (32) |

76 (24) |

68 (20) |

106 (41) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 30.8 (−0.7) |

33.5 (0.8) |

41.9 (5.5) |

51.0 (10.6) |

61.3 (16.3) |

71.5 (21.9) |

78.7 (25.9) |

78.4 (25.8) |

71.3 (21.8) |

59.2 (15.1) |

46.4 (8.0) |

35.8 (2.1) |

55.0 (12.8) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 22.7 (−5.2) |

24.6 (−4.1) |

33.7 (0.9) |

43.2 (6.2) |

53.0 (11.7) |

63.2 (17.3) |

70.1 (21.2) |

70.0 (21.1) |

62.5 (16.9) |

50.4 (10.2) |

38.5 (3.6) |

28.2 (−2.1) |

46.7 (8.2) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 14.6 (−9.7) |

15.7 (−9.1) |

25.4 (−3.7) |

35.4 (1.9) |

44.8 (7.1) |

54.8 (12.7) |

61.5 (16.4) |

61.6 (16.4) |

53.7 (12.1) |

41.6 (5.3) |

30.6 (−0.8) |

20.5 (−6.4) |

38.4 (3.6) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −26 (−32) |

−29 (−34) |

−15 (−26) |

10 (−12) |

18 (−8) |

29 (−2) |

40 (4) |

36 (2) |

27 (−3) |

11 (−12) |

−10 (−23) |

−22 (−30) |

−29 (−34) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 1.76 (45) |

1.48 (38) |

1.91 (49) |

3.78 (96) |

3.90 (99) |

4.17 (106) |

3.61 (92) |

3.68 (93) |

3.08 (78) |

2.56 (65) |

2.13 (54) |

1.82 (46) |

33.88 (861) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 13.2 (34) |

10.7 (27) |

6.0 (15) |

0.8 (2.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.9 (2.3) |

10.7 (27) |

42.3 (107) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 8.1 | 6.7 | 7.7 | 9.9 | 11.1 | 10.4 | 8.7 | 8.1 | 7.8 | 9.1 | 7.6 | 7.8 | 103.0 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 6.4 | 5.1 | 2.7 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.9 | 4.6 | 20.2 |

| Source: NOAA[41][42] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1880 | 1,386 | — | |

| 1890 | 1,649 | 19.0% | |

| 1900 | 3,010 | 82.5% | |

| 1910 | 3,792 | 26.0% | |

| 1920 | 3,340 | −11.9% | |

| 1930 | 3,693 | 10.6% | |

| 1940 | 4,046 | 9.6% | |

| 1950 | 4,755 | 17.5% | |

| 1960 | 5,984 | 25.8% | |

| 1970 | 8,752 | 46.3% | |

| 1980 | 8,612 | −1.6% | |

| 1990 | 9,338 | 8.4% | |

| 2000 | 10,467 | 12.1% | |

| 2010 | 11,250 | 7.5% | |

| 2020 | 12,353 | 9.8% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[43] | |||

2000 census

[edit]As of the census of 2000,[44] there were 10,467 people residing in Port Washington. The racial makeup of the city was 97.0% White, 0.7% Black or African American, 0.5% Asian, 0.4% Native American, 0% Pacific Islander, 0.6% from other races, and 0.89% from two or more races. 1.5% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

There were 3,244 families and 4,763 households, of which 34.0% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 57.5% were married couples living together, 7.4% had a female householder with no husband present and 31.9% were non-families. The householder lives alone in 26.3% of all households, and 10.5% of householders were aged 65 or older. The average household size was 2.49 and the average family size was 3.05.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 6.6% under the age of 5, 74.2% aged 18 and over, and 13.2% 65 years and over. The median age was 36.7 years. The population is 50.4% female and 49.6% male.

In 1999 the median income for a family was $62,557. The per capita income for the city was $24,770. About 2.6% of families and 4.0% of the population were below the poverty line.

2010 census

[edit]As of the census[2] of 2010, there were 11,250 people, 4,704 households, and 2,956 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,933.0 inhabitants per square mile (746.3/km2). There were 5,020 housing units at an average density of 862.5 per square mile (333.0/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 95.0% White, 1.6% African American, 0.4% Native American, 0.7% Asian, 0.8% from other races, and 1.4% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 3.1% of the population.

There were 4,704 households, of which 29.2% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 51.0% were married couples living together, 8.3% had a female householder with no husband present, 3.5% had a male householder with no wife present, and 37.2% were non-families. 31.0% of all households were made up of individuals, and 11.9% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.31 and the average family size was 2.91.

The median age in the city was 39.5 years. 22.4% of residents were under the age of 18; 7.6% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 28.2% were from 25 to 44; 27% were from 45 to 64; and 14.7% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 49.0% male and 51.0% female.

Economy

[edit]

Port Washington's early economy was heavily based on harvesting and shipping raw materials from natural resources, including lumber, fish, fur, wheat and rye,[12] and beginning in the 1870s, dairy farming played an increasingly important role in the Town of Port Washington's economy with creameries and cheese factories in rural hamlets like Knellsville.[45] By the mid-20th century, dairy farming accounted for 80% of agriculture in the Port Washington area.

In the 1880s and 1890s, Port Washington became increasingly industrial, with the Wisconsin Chair Company being the largest employer. In the 20th century, other manufacturers in the community included Allen Edmonds, Bolens Corporation, Koering Co., Simplicity Manufacturing Company, and Trak International. While Allen Edmonds continues to manufacture high-end shoes in the city, many of the other manufacturers closed or were purchased by larger companies between the 1970s and 2000s.[5] In 2001, MTD Products acquired the Bolens Corporation. In 2004, Briggs & Stratton purchased Simplicity Manufacturing and closed the Port Washington plant in October 2008. As of 2015, manufacturing accounted for approximately 25% of Port Washington's jobs,[46] a significant decrease from the early 20th century when the Wisconsin Chair Company alone accounted for 50% of the city's jobs.[23]

In the early 21st century, public administration plays a significant role in Port Washington's economy, accounting for approximately 20% of jobs. Port Washington is the Ozaukee County seat, and the county government is the largest employer in the city. The Port Washington city administration is also a major employer.[46]

| Largest Employers in Port Washington, 2015[46] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Employer | Industry | Employees |

| 1 | Ozaukee County | Public administration | 500–999 |

| 2 | Kleen Test Products | Cleaning product manufacturing | 250–499 |

| 3 | Allen Edmonds | Footwear and high-end apparel manufacturing | 250–499 |

| 4 | Kickhaefer Manufacturing Company | OEM metal fabrication and stamping | 250–499 |

| 5 | Port Washington-Saukville School District | Primary and secondary education | 100–249 |

| 6 | City of Port Washington | Public Administration | 100–249 |

| 7 | Franklin Energy Services | Energy efficiency consultant | 100–249 |

| 8 | Construction Forms Inc. | Pipe and pipe fitting manufacturing | 50–99 |

| 9 | Aurora Health Care | Health care | 50–99 |

| 10 | Heritage Nursing & Rehabilitation | Nursing care facility | 50–99 |

Culture

[edit]Events

[edit]Port Washington hosts many annual events tied to the community's maritime heritage. Each year on January 1, the city is the site of a polar bear plunge in which over 100 people jump into Lake Michigan.[37] Fish Day, billed as the "world's largest one-day outdoor fish fry," has been held annually since 1964 on the third Saturday in July. Hosted by several area philanthropic organizations, the event is a charity fundraiser.[47] In the summer, Port Washington hosts a Festival of the Arts, as well as several yacht races and sport fishing competitions,[37] one of which is part of the festival hosted by the area Lions Club.[48]

The city also hosts public celebrations for Independence Day, Labor Day, Halloween, and Christmas.[37]

Museums

[edit]

- Judge Eghart House: Built in 1872, the Judge Eghart House museum is furnished with Victorian era artifacts to provide a snapshot of what life was like in late 19th century Port Washington.[49]

- Port Washington Light: Port Washington's light station was constructed in 1860 to replace and earlier structure and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The government of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg paid to restore the lighthouse in 2000, because of the cultural ties between northern Ozaukee County and Luxembourg.[50] The building is a museum of 19th-century lighthouse keeping, and the Port Washington Historical Society runs tours on summer weekends.[51]

Religion

[edit]

The Port Washington area has three Lutheran congregations: Christ the King Lutheran Church, which is affiliated with the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America;[52] St. John's Lutheran Church, which is affiliated with the Missouri Synod;[53] and St. Matthew Evangelical Lutheran Church, which is affiliated with the Wisconsin Evangelical Lutheran Synod.[54] In addition to Christ the King Lutheran Church, other mainline Protestant congregations include the First Congregational Church of Port Washington,[55] Grand Avenue United Methodist Church,[56] and St. Simon the Fisherman Episcopal Church.[57] Faith Baptist Church is a denominational Protestant church in the community in the Continental Baptist tradition.[58]

St. John XXIII Catholic Parish formed in 2016 from the merger of Port Washington's two historic Catholic churches—St. Mary's Church and St. Peter of Alcantara Church—with Immaculate Conception Catholic Church in neighboring Saukville. While the parish is one financial entity, the three church buildings remain in use, and the parish operates a parochial school for students from kindergarten through eighth grade.[59][60]

There are two evangelical churches in the area: the Evangelical Free Church of America-affiliated Friedens Church[61] and Portview Church.[62] Open Door Bible Church is a Christian fundamentalist congregation in the community affiliated with IFCA International.[63]

Port Washington also has a Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and a Jehovah's Witnesses Kingdom Hall.[64]

W. J. Niederkorn Library

[edit]The Port Washington Woman’s Club established the city's first public library in 1899, which got its own building in 1961, when area resident W. J. Niederkorn paid to construct it on Grand Avenue. It provides books, magazines, computers, printers, study rooms, databases, audiobooks, e-books, and language-learning software. It is a member of the Monarch Library System, comprising thirty-one libraries in Ozaukee, Sheboygan, Washington, and Dodge counties.[65]

Law and government

[edit]Port Washington has a mayor–council government. The mayor is Ted Neitzke IV, who was elected to his first term on April 6, 2021.[66] Seven aldermen sit on the city council. A full-time staff of unelected administrators manage the city's day-to-day operations.[67]

As part of Wisconsin's 6th congressional district, Port Washington is represented by Glenn Grothman (R) in the United States House of Representatives, and by Ron Johnson (R) and Tammy Baldwin (D) in the United States Senate. Duey Stroebel (R) represents Port Washington in the Wisconsin State Senate, and Robert Brooks (R) represents Port Washington in the Wisconsin State Assembly.[68]

| # | Mayor | Term in Office | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | James W. Vail | 1882–1883 | |

| 2 | Henry B. Schwin | 1883–1887 | |

| 3 | Henry W. Lyman | 1887–1888 | |

| 4 | Reinhard Stelling | 1887–1888 | |

| 5 | Charles A. Mueller | 1888–1892 | |

| 6 | Reinhard Stelling | 1892–1893 | |

| 7 | B. Biedermann | 1893–1895 | |

| 8 | Edward B. Bostwick | 1895–1896 | |

| 9 | Charles A. Mueller | 1896–1906 | |

| 10 | Harry W. Bolens | 1906–1908 | |

| 11 | Rheinhold E. Maercklein | 1908–1910 | |

| 12 | Harry W. Bolens | 1910–1914 | |

| 13 | John Kaiser Jr. | 1914–1923 | |

| 14 | George H. Adams | 1923 – August 9, 1923 | Resigned. |

| - | Adolph H. Kuhl | August 9, 1923 – January 9, 1924 | Acting mayor. |

| 15 | Albert W. Grady | January 9, 1924 – April 16, 1929 | |

| 16 | August F. Kruke | April 16, 1929 – April 18, 1939 | |

| 17 | John Kaiser Jr. | April 18, 1939 – April 17, 1945 | |

| 18 | George S. Cassels | April 17, 1945 – April 15, 1947 | |

| 19 | Charles Larson | April 15, 1947 – April 19, 1949 | |

| 20 | John Kaiser Jr. | April 19, 1949 – April 19, 1955 | |

| 21 | Paul Schmit | April 19, 1955 – April 25, 1961 | |

| 22 | Frank Meyer | April 25, 1961 – April 20, 1971 | |

| 23 | James R. Stacker | April 20, 1971 – April 13, 1977 | Died. |

| - | Robert Lorge | April 13, 1977 – May 17, 1977 | Acting. Resigned. |

| 24 | George Lampert | May 17, 1977 – April 19, 1988 | Acting mayor until April 1978. |

| 25 | Ambrose Mayer | April 19, 1988 – April 16, 1991 | |

| 26 | Mark Dybdal | April 16, 1991 – April 19, 1994 | |

| 27 | Joseph Dean | April 19, 1994 – April 1997 | |

| 28 | Mark Gottlieb | April 1997 – April 2003 | |

| 29 | Scott A. Huebner | April 2003 – April 2012 | |

| 30 | Tom Mlada | April 2012 – April 2018 | |

| 31 | Martin Becker | April 2018 – April 2021 | |

| 32 | Ted Neitzke IV | April 2021 – present |

Mayoral Election Results

[edit]| Candidates | Votes | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Scott A. Huebner (incumbent) | 1,434 | 97.41% |

| Write-in Votes | 38 | 2.59% |

| Candidates | Votes | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Jim Vollmar | 1,370 | 46.66% |

| Tom Mlada | 1,555 | 52.96% |

| Write-in Votes | 11 | 0.37% |

| Candidates | Votes | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Tom Mlada (incumbent) | 2,128 | 97.97% |

| Write-in Votes | 44 | 2.03% |

| Candidates | Votes | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Martin Becker | 1,922 | 67.20% |

| Adele Richert | 928 | 32.45% |

| Write-in Votes | 10 | 0.35% |

| Candidates | Votes | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Ted Neitzke IV | 1,796 | 64.63% |

| Dan Benning | 979 | 35.23% |

| Write-in Votes | 4 | 0.14% |

Fire department

[edit]The Port Washington Fire Department formed in 1852. The department operates one fire station on Washington Street and had fifty-nine personnel as of December 31, 2018. Mark Mitchell serves as fire chief. The department has four divisions: fire, emergency medical services, dive team, and rescue task force. The rescue task force was formed in 2016 as a collaboration between law enforcement and paramedics to prepare for a mass-casualty active shooter situation. It was the first such task force in Ozaukee County.[74]

The department operates three ambulances, four fire engines, a water tanker, a Pierce heavy rescue truck, a Pierce ladder truck, a dive rescue boat, and a fireboat.[75]

Police department

[edit]The Port Washington Police Department was established in 1882 when the city incorporated. The police station is located on Wisconsin Street in Downtown Port Washington. The department employs twenty sworn officers, including police chief Kevin Hingiss who has served with the department since 1984 and was appointed chief in 2012. Additionally, the department has a civilian support staff of three full-time records management employees, one municipal court clerk, one administrative assistant, one parking enforcement officer and one custodian.[76]

Education

[edit]Port Washington is served by the joint Port Washington-Saukville School District. The district has three elementary schools for kindergarten through fourth grade. Students in northern and eastern Port Washington attend Lincoln Elementary, while students southern and western neighborhoods attend Dunwiddie Elementary. Saukville Elementary serves students in the western parts of the Town of Port Washington and the Town and Village of Saukville. All students in the district attend Thomas Jefferson Middle School for fifth through eighth grades, and Port Washington High School for ninth through twelfth grades.

The district is governed by a nine-member elected school board, which meets on Mondays at 6 p.m. in the District Office Board Room, 100 W. Monroe Street, Port Washington. The district also has a full-time superintendent: Michael R. Weber.[77]

Additionally, St. John XXIII Catholic Parish (of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Milwaukee) operates a parochial school in the city for students from kindergarten through eighth grade.[60]

Transportation

[edit]Interstate 43 passes around Port Washington to the city's west and north with access via Exit 100. Wisconsin Highway 32 passes north to south through the city while Wisconsin Highway 33 travels from the west before it terminates downtown. Wisconsin Highway 57 runs several miles west of Port Washington with a junction with Interstate 43 in the Village of Saukville.

Port Washington Harbor was constructed by the U.S. Federal Government in the early 1870s as a commercial port. Because Port Washington does not have a natural harbor, the government must dredge the harbor every few decades to prevent the twelve-foot-deep channels from filling with sediment. The Port Washington Generating Station on the southern shore received daily shipments of coal through the harbor until 2004, when it became a natural gas power plant. When the coal shipments stopped, the commercial port closed, but the community continues to operate a marina for recreational boaters[78] from April 1 through November 1.[37]

Port Washington has limited public transit compared with larger cities. Ozaukee County and the Milwaukee County Transit System run the Route 143 commuter bus, also known as the "Ozaukee County Express," to Milwaukee via Interstate 43. The closest stop is the route's northern terminus at the Saukville Walmart parking lot, near Interstate 43 Exit 96. The bus operates Monday through Friday with limited hours corresponding to peak commute times.[79][80] Ozaukee County Transit Services' Shared Ride Taxi is the public transit option for traveling to sites not directly accessible from the interstate. The taxis operate seven days a week and make connections to Washington County Transit and Milwaukee County Routes 12, 49 and 42u. Unlike a typical taxi, however, the rider must contact the service ahead of time to schedule their pick-up date and time. The taxi service plans their routes based on the number of riders, pick-up/drop-off time and destination then plans the routes accordingly.[79][81]

The City of Port Washington has sidewalks in most areas for pedestrian traffic. Additionally, the Ozaukee Interurban Trail for pedestrian and bicycle use runs north-south through the city and connects Port Washington to the neighboring communities of Grafton in the south and Belgium in the north. The trail continues north to Oostburg in Sheboygan County and south to Brown Deer where it connects with the Oak Leaf Trail. The trail was formerly an interurban passenger rail line that ran from Milwaukee to Sheboygan with a stop in Port Washington, which was the halfway point between the northern and southern terminuses. The train was in operation from 1907 to 1948, when it fell into disuse following World War II. The old rail line was converted into the present recreational trail in the 1990s.

The city does not have passenger rail service, but the Union Pacific Railroad operates freight trains in the community.[82]

Parks and recreation

[edit]The City of Port Washington maintains twenty-nine public parks with amenities including picnic shelters, baseball and softball fields, tennis courts, nature preserves, and a public pool. The parks and recreation department offers recreation programs for residents and facilitates men's basketball and softball leagues as well as women's volleyball and fastpitch leagues.[83] The City also has Possibility Playground, an accessible playground designed to be used by children with special needs.

The Port Washington marina is open for recreational boaters from April through November. Fishers can also use the breakwaters to catch lake trout and Chinook salmon. Each summer the Port Washington Yacht Club hosts a double-handed (two-person crew) sailboat race in late June and the across-the-lake "Clipper Club" sailboat race on the second Friday in August. The Great Lakes Sport Fishermen—Ozaukee Chapter hosts the Great Lakes Sport Fishing Derby in Port Washington from July 1 through July 3, and the local chapter of the Lions Club hosts a fishing contest on the last weekend in July.[37]

The Ozaukee Interurban Trail runs through the City of Port Washington, following the former route of the Milwaukee Interurban Rail Line. The southern end of the trail is at Bradley Road in Brown Deer which connects to the Oak Leaf Trail (43°09′48″N 87°57′39″W / 43.16333°N 87.96083°W), and its northern end is at DeMaster Road in the Village of Oostburg Sheboygan County (43°36′57″N 87°48′08″W / 43.61583°N 87.80222°W). The trail connects the community to neighboring Grafton and Belgium.

The Wisconsin Shipwreck Coast National Marine Sanctuary, established in 2021 and the site of a large number of historically significant shipwrecks, lies in the waters of Lake Michigan off Port Washington.[84][85][86]

In popular culture

[edit]The television sitcom Step by Step was set in a fictionalized version of Port Washington.[87] The show was filmed at Warner Bros. Studios in Burbank, California, and the establishing shots of the main characters' home were actually of a house in South Pasadena, California, not Port Washington.[88]

Notable people

[edit]

- A. Manette Ansay, writer[89]

- Vernon Biever, photographer[90]

- Edward Reed Blake, politician[91]

- John R. Bohan, politician[92][93]

- Harry W. Bolens, politician[94]

- Alice Duff Clausing, politician[95]

- John DeMerit, Major League Baseball player[96]

- Peter V. Deuster, U.S. diplomat and politician[97]

- Dustin Diamond, actor[98][99]

- Alex Dieringer, folkstyle and freestyle wrestler[100]

- Marc C. Duff, politician[101]

- Josh Gasser, professional basketball player[102]

- Janine P. Geske, jurist[103]

- Warren A. Grady, politician[104]

- Henry Hase, politician[105]

- Adolph F. Heidkamp, politician[106]

- William E. Hoehle, politician[107]

- Beany Jacobson, Major League Baseball player[108]

- Mitch Jacoby, National Football League player[109]

- David W. Opitz, politician[110]

- M. Rickert, writer[111]

- Mike Seifert, National Football League player[112]

- Leland Stanford, United States Senator, 8th Governor of California, and founder of Stanford University[113][114][115]

- Donald K. Stitt, Chairman of the Republican Party of Wisconsin[116]

- Rich Strenger, National Football League player[117]

- Eugene S. Turner, legislator[118]

- Samuel A. White, politician[119]

- Al Wickland, Major League Baseball player[120]

- Albert J. Wilke, politician[121]

Sister city

[edit]Port Washington's sister city is Sassnitz, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Germany (since 2017).[122]

References

[edit]- ^ "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- ^ a b "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved November 18, 2012.

- ^ "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- ^ "Newland Became Cedarburg". The Milwaukee Sentinel. September 4, 1967. pp. Part 5, Page 5. Retrieved April 23, 2015.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c d e f "Encyclopedia of Milwaukee: City of Port Washington". University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. Retrieved January 2, 2020.

- ^ Price 1943, pp. 7–8

- ^ Chicago and North Western Railway Company (1908). A History of the Origin of the Place Names Connected with the Chicago & North Western and Chicago, St. Paul, Minneapolis & Omaha Railways. p. 115.

- ^ Price 1943, p. 11

- ^ Price 1943, p. 20

- ^ "Washington County Wisconsin Town History". Wisconsin Genealogy Trails. Retrieved October 25, 2018.

- ^ a b "Encyclopedia of Milwaukee: Ozaukee County". University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. Retrieved January 11, 2020.

- ^ a b Price 1943, p. 31

- ^ "Wisconsin Shipwrecks: Toledo (1854)". Wisconsin Historical Society. Retrieved January 2, 2020.

- ^ Price 1943, pp. 32–33

- ^ Price 1943, p. 33

- ^ a b Price 1943, p. 35

- ^ "Civil War: Draft Riots (1862)". Wisconsin Historical Society. August 3, 2012. Retrieved January 4, 2020.

- ^ Gurda, John (1999). "Chapter 3. Here Come the Germans, 1846-1865". The Making of Milwaukee. Milwaukee County Historical Society. p. 97.

- ^ Price 1943, pp. 55–56

- ^ Price 1943, pp. 56–57

- ^ Wisconsin Magazine of History, Volumes 48-49 (1964), pg. 223

- ^ "God Raised Us Up Good Friends: (Letters from) English Immigrants in Wisconsin." Wisconsin Magazine of History 47 (Summer 1964): 224-37

- ^ a b c Price 1943, p. 59

- ^ "Smith Bros. Family History". Christmaswhistler.web44.net. Archived from the original on January 29, 2016. Retrieved November 14, 2021.

- ^ "Port Washington, Wisconsin - A Brief History". Wisconsin Historical Society. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- ^ Price 1943, pp. 60–61

- ^ Price 1943, p. 64

- ^ "The Milwaukee Northern Railway". Electric Railway Review. XVIII (23): 882–890. December 7, 1907. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- ^ "Milwaukee Northern Interurban". Ozaukee County. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- ^ "Fishing Industry in Wisconsin". Wisconsin Historical Society. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- ^ "Encyclopedia of Milwaukee: Commercial Fishing". University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- ^ Bernier, Brian (October 26, 2016). "Smith Bros. Coffee House serves a bit of history". Sheboygan Press. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- ^ "Port Washington Tornado August 22, 1964". Ozaukee County Land Information Office. Retrieved January 7, 2020.

- ^ "Port Washington Twister Loss May Be $2 Million; No Deaths". Sheboygan Press. Retrieved January 7, 2020.

- ^ "CPI Inflation Calculator". U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Retrieved January 7, 2020.

- ^ "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on January 25, 2012. Retrieved November 18, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Inventory of Agricultural, Natural, and Cultural Resources". Ozaukee County. Retrieved January 20, 2020.

- ^ a b "Central Lake Michigan Coastal Ecological Landscape" (PDF). Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. Retrieved January 20, 2020.

- ^ "Ecological Landscapes of Wisconsin" (PDF). Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. Retrieved February 13, 2020.

- ^ Durhams, Sharif (June 5, 2010). "Port Washington bear tranquilized, sent packing". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- ^ "NowData - NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on May 8, 2021. Retrieved June 15, 2021.

- ^ "Station: Port Washington, WI". U.S. Climate Normals 2020: U.S. Monthly Climate Normals (1991-2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 15, 2021.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ Price 1943, p. 57

- ^ a b c Pawasarat, Kate (July 2015). "City of Port Washington Community Economic Profile 2015" (PDF). Retrieved May 4, 2020.

- ^ "Port Fish Day". Port Fish Day. Retrieved May 4, 2020.

- ^ "Port Washington Lions Club". Port Washington Lions Club. Retrieved May 4, 2020.

- ^ "Judge Eghart House: A Victorian Restoration". W. J. Niederkorn Museum and Art Center. Retrieved May 4, 2020.

- ^ Pepper, Terry. "Port Washington Main Lighthouse". Retrieved February 11, 2012.

- ^ "1860 Light Station". Port Washington Historical Society. Archived from the original on June 21, 2020. Retrieved May 4, 2020.

- ^ "Christ the King Lutheran Church". Christ the King Lutheran Church. Retrieved May 4, 2020.

- ^ "St. John's Lutheran Church: What We Believe". St. John's Lutheran Church. February 25, 2014. Retrieved May 4, 2020.

- ^ "St. Matthew Evangelical Lutheran Church". St. Matthew Evangelical Lutheran Church. Retrieved May 4, 2020.

- ^ "First Congregational Church". First Congregational Church. Retrieved May 4, 2020.

- ^ "Grand Avenue United Methodist Church". Grand Avenue United Methodist Church. Retrieved May 4, 2020.

- ^ "St. Simon the Fisherman Episcopal Church". St. Simon the Fisherman Episcopal Church. Retrieved May 4, 2020.

- ^ "Faith Baptist Church". Faith Baptist Church. Retrieved May 4, 2020.

- ^ "St. John XXIII Catholic Parish: History of our Parish". St. John XXIII Catholic Parish. Retrieved May 4, 2020.

- ^ a b "St. John XXIII Catholic School". St. John XXIII Catholic Church. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- ^ "Friedens Church: What We Believe". Friedens Church. Retrieved May 4, 2020.

- ^ "Portview Church: Purposes & Values". Portview Church. Retrieved May 4, 2020.

- ^ "Open Door Bible Church: Our Story and Vision". Open Door Bible Church. Retrieved May 4, 2020.

- ^ Johnson, Annysa (January 8, 2010). "Mormon congregation gets its own facility in Port Washington". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. Retrieved May 4, 2020.

- ^ "W. J. Niederkorn Library: About". W. J. Niederkorn Library. Retrieved May 4, 2020.

- ^ Morales, Eddie (April 6, 2021). "Ted Neitzke becomes Port Washington's new mayor after easily winning the election". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. Retrieved June 24, 2021.

- ^ "City of Port Washington, Wisconsin". City of Port Washington, Wisconsin. Retrieved May 4, 2020.

- ^ "Wisconsin State Legislature Map". Wisconsin State Legislature. Retrieved January 17, 2020.

- ^ "Spring election Ozaukee county, Wisconsin - Final official results". Archived from the original on November 2, 2014.

- ^ "Presidential preference vote - Ozaukee County, Wisconsin - Official final results". April 3, 2012.

- ^ "Ozaukee County, Wisconsin - Official final results". April 7, 2015.

- ^ "Ozaukee County, Wisconsin - Unofficial results". April 3, 2018.

- ^ "Spring election Ozaukee county, Wisconsin - Final official results". Archived from the original on February 7, 2023.

- ^ "Port Washington Fire Department". Port Washington Fire Department. Retrieved May 4, 2020.

- ^ "Port Washington Fire Department: 2018 Annual Report" (PDF). Port Washington Fire Department. March 11, 2019. Retrieved May 4, 2020.

- ^ "Port Washington Police Department". Port Washington Police Department. Retrieved May 4, 2020.

- ^ "Port Washington-Saukville School District". Port Washington-Saukville School District. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- ^ "Port Washington Harbor, WI" (PDF). U.S. Army Corps of Engineers: Detroit District. Retrieved May 4, 2020.

- ^ a b "MCTS Route 143: Ozaukee County Express". Wisconsin DOT. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- ^ "Ozaukee County, Cedarburg (I-43/County C)". Milwaukee County Transit System. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- ^ "OCTS: Shared Ride Taxi". Ozaukee County Transit Services. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- ^ "Wisconsin Railroads and Harbors 2020" (PDF). Wisconsin DOT. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- ^ "Port Washington Parks and Recreation". City of Port Washington. Retrieved May 4, 2020.

- ^ "Wisconsin Shipwreck Coast National Marine Sanctuary Designation; Final Regulations". NOAA via Federal Register. June 23, 2021. Retrieved June 29, 2021.

- ^ "National Marine Sanctuaries media document: Wisconsin Shipwreck Coast National Marine Sanctuary Accessed 29 June 2021" (PDF).

- ^ "NOAA designates new national marine sanctuary in Wisconsin's Lake Michigan | National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration". www.noaa.gov. June 22, 2021.

- ^ "Step by Step". TV.com. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- ^ "Step by Step: The Wall". IMDB. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- ^ Biography. A. Manette Ansay.

- ^ Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. "He's always been in the picture for Packers" Archived February 12, 2005, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Heg, James E. (1885). The Blue Book of the State of Wisconsin. Madison, WI: Democrat Printing Co. pp. 425.

- ^ Turner, A. J. (1872). The Legislative Manual of the State of Wisconsin. Madison, WI: Atwood & Culver. pp. 454.

- ^ "N. G. Bohan [sic]". The Weekly Wisconsin. November 20, 1886. p. 7. Retrieved August 8, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Ohm, Howard F.; Bryhan, Leone G. (1940). The Wisconsin Blue Book, 1940. Madison, WI: Democrat Printing Co. pp. 31.

- ^ "Clausing, Alice 1944". Wisconsin Historical Society. Archived from the original on November 3, 2012. Retrieved November 17, 2011.

- ^ John DeMerit | Society for American Baseball Research Retrieved October 13, 2018.

- ^

- United States Congress. "Port Washington, Wisconsin (id: D000274)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- ^ "Milwaukee Journal Sentinel". Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- ^ "Arrested, accused in stabbing at bar, Dustin Diamond aka "Screech" has Monday court hearing". FOX6Now.com. December 26, 2014. Archived from the original on September 9, 2015. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- ^ J. Carl Guymon (October 30, 2015). "OSU Sports Extra - OSU's Alex Dieringer, OU's Cody Brewer claim titles at NCAA wrestling championships". Tulsaworld.com. Retrieved April 9, 2016.

- ^ "Members of State Legislature" (PDF). Wisconsin Blue Book. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 13, 2012. Retrieved June 19, 2013.

- ^ "Josh Gasser Wisconsin Badgers profile". uwbadgers.com. Archived from the original on March 16, 2013. Retrieved March 29, 2014.

- ^ "Janine P. Geske (1949- )". Wisconsin Court System. March 7, 2012. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

- ^ "Members of the Assembly". Wisconsin Blue Book. 1960. Retrieved November 29, 2013.

- ^ 'History of Milwaukee, City and County,' Josiah Seymour Green, SJ Clark: 1922, vol. 3, pg. 405-406

- ^ "Adolph F. Heidkamp". Political Graveyard. Retrieved October 31, 2011.

- ^ Froehlich, William H. (1899). The Blue Book of the State of Wisconsin. Madison, WI: Democrat Printing Co. pp. 768.

- ^ "Beany Jacobson Stats". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved November 14, 2021.

- ^ "Mitch Jacoby". Pro-Football-Reference.com. Retrieved February 20, 2011.

- ^ "Opitz, David W. 1945". Wisconsin Historical Society. Archived from the original on October 13, 2013. Retrieved October 25, 2013.

- ^ Adams, John Joseph (December 11, 2006). "Interview: M. Rickert". Strange Horizons. Retrieved December 11, 2006.

- ^ "Mike Seifert Stats". Pro-Football-Reference.com. Retrieved November 14, 2021.

- ^ Price 1943, p. 22

- ^ Barr 1965, p. 60

- ^ "Wisconsin Historical Marker 557: Leland Stanford (1824-1893)". WisconsinHistoricalMarkers.com. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- ^ "Donald Kyle Stitt". Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel. September 22, 2014. Retrieved September 17, 2016.

- ^ "Rich Strenger Stats". Pro-Football-Reference.com. Retrieved November 14, 2021.

- ^ Journal of the Assembly of Wisconsin. Cantwell Printing Company. 1915. pp. 1422–1423. Retrieved November 6, 2014.

- ^ 'Proceedings of the State Bar Association of Wisconsin,' vol 1, Wisconsin State Bar Association; 1905, Biographical Sketch of Samuel A. White, pg. 253

- ^ "Al Wickland Stats". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved November 14, 2021.

- ^ "Albert J. Wilke". Political Graveyard. Retrieved October 31, 2011.

- ^ "Stadt Sassnitz: Partnerstädte". City of Sassnitz. Retrieved September 6, 2020.

- Barr, Jeanette (1965). Early history of Ozaukee County, Wisconsin. University of Wisconsin.

- Price, Mary Jane Frances (1943). The History of Port Washington, in Ozaukee, Wisconsin. DePaul University.

External links

[edit]Port Washington, Wisconsin

View on GrokipediaPort Washington is a city in and the county seat of Ozaukee County, Wisconsin, United States, located on the western shore of Lake Michigan approximately 25 miles north of Milwaukee.[1][2] As of the 2020 United States census, the population was 12,353.[3] Founded in 1835 as Wisconsin City by settler Wooster Harrison and renamed Port Washington shortly thereafter, the city emerged as a key port for exporting lumber, fish, and agricultural goods during the 19th century.[1] Its economy later shifted toward manufacturing, notably including furniture production via the Wisconsin Chair Company and footwear by Allen Edmonds, alongside ongoing commercial fishing operations.[4][5] The city's defining features include its historic harbor, the iconic Port Washington Lighthouse established in 1889, and a preserved downtown district reflecting its industrial heritage.[4]

History

Pre-settlement and early settlement

The area encompassing present-day Port Washington was inhabited by Native American tribes including the Potawatomi, Menominee, Sauk, and Fox prior to European contact, with these groups utilizing the Lake Michigan shoreline for seasonal activities such as hunting, fishing, and trade routes along the Green Bay Trail.[6][7] Archaeological and historical records indicate transient rather than permanent settlements, tied to the region's natural resources like fish and game, though specific sites in Port Washington remain limited in documentation.[4] Potawatomi bands were among the primary occupants in the immediate pre-contact period, engaging in fur trade interactions with early French explorers.[6] Early European exploration reached the area in the late 17th century, with French explorer René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, noted as one of the first documented non-Native visitors during his 1679-1680 expedition along Lake Michigan's coast, though no permanent European presence followed at that time.[8] Systematic settlement began after the 1833 Treaty of Chicago, which facilitated the cession of Potawatomi lands and their forced removal from Wisconsin territories between 1835 and 1850, clearing the region for American expansion.[4][9] The first permanent white settlers arrived in 1835, led by Wooster Harrison, a land speculator and trader known locally as General Harrison, who organized a company to claim property at the mouth of Sauk Creek.[8][10] Harrison's group acquired the initial government land sale in Ozaukee County on November 24, 1835, totaling several sections platted as "Wisconsin City," which served as the foundation for the future town.[6] Early economic activities centered on land speculation, rudimentary fishing from the natural harbor, and small-scale farming on cleared plots, with settlers relying on lake transport for supplies amid challenges like food shortages.[7] In December 1836, Wisconsin City was designated the seat of justice for Washington County (predecessor to Ozaukee County), affirming its early administrative role despite sparse population.[7][8]19th-century industrialization and growth

The lime industry formed the backbone of Port Washington's early industrialization in the mid-19th century, capitalizing on local Silurian dolomite deposits quarried near the Lake Michigan shoreline. Limestone from these quarries was processed in kilns into lime for construction and agricultural uses, with the natural harbor facilitating bulk shipments to regional markets. Operations such as the Ormsby Lime Company, established in 1847, produced approximately 25 barrels daily, contributing to Wisconsin's statewide output surpassing one million barrels annually by the 1880s.[11][12] Complementing extractive activities, manufacturing expanded with the establishment of sawmills as early as 1847 by entrepreneurs like Harvey and S.A. Moore, processing local timber for building materials. The pivotal development came in 1888 with the founding of the Wisconsin Chair Company, which repurposed a bankrupt sash and door factory to produce furniture, employing hundreds and diversifying output to include beds and cabinets. This industrial scaling, alongside lime shipping, drove economic growth, reflected in the city's incorporation in 1882 under a mayoral-aldermanic government.[10][4][13] Population surged from 1,386 in 1880 to 3,010 by 1900, propelled by job opportunities that attracted German and Irish immigrants, who established businesses and filled factory roles. German-speaking settlers, arriving from the 1850s, integrated into the workforce and commerce, while Irish arrivals in the 1840s-1860s bolstered labor pools amid broader waves to Wisconsin. These demographic shifts supported sustained expansion until the century's end, before later transitions.[4][14][15]20th-century transitions and suburban expansion

The population of Port Washington more than doubled between 1940 (4,046 residents) and 1970 (8,890 residents), reflecting broader suburban migration from Milwaukee amid post-World War II economic expansion and white-collar job growth in the metropolitan area.[16] This surge involved annexations of adjacent rural townships, converting farmland into residential subdivisions and enabling longer commutes via upgraded state highways like Wisconsin Highway 32, which paralleled Lake Michigan.[4] The onset of Interstate 43 construction in 1972, connecting Port Washington southward to Milwaukee over 94 miles through Ozaukee County, accelerated this trend by reducing travel times and accommodating automobile-dependent households, with the corridor fully operational by 1981.[17] Traditional extractive sectors waned as economic pressures mounted. Wisconsin's lime production, centered in Ozaukee County kilns including those near Port Washington, peaked before the Great Depression and continued declining through the mid-20th century due to depleting high-quality dolomite reserves, rising fuel costs, and substitution by cement in construction.[18] Commercial fishing in Lake Michigan, a staple employing generations in Port Washington tugs and processing, faced sharp reductions by the 1950s–1960s from overexploitation, invasive species like the alewife, and industrial pollution, shifting output from whitefish and perch to less viable chubs.[19] These losses were mitigated by enduring manufacturing, notably the Wisconsin Chair Company's facilities producing furniture and phonograph cabinets, which sustained employment through the early-to-mid century despite national market fluctuations.[20] Harbor enhancements and renewal initiatives underscored infrastructural adaptation. Federal improvements in 1931 dredged and extended breakwaters, modernizing the port for residual coal shipments to the local generating station and recreational use, even as commercial tonnage fell.[9] By the 1970s, the city's Community Development Authority spearheaded rehabilitation of aging downtown structures, fostering retail and service outlets to serve growing commuter populations and tourists, evidenced by stabilized employment data amid industrial contraction.[21]21st-century economic diversification and infrastructure projects

In the early 2000s, Port Washington's economy remained anchored in manufacturing, which employed 1,547 residents as of recent data, supporting steady population growth to 12,353 by the 2020 census alongside a median household income rise to $81,582 from $76,609 in the prior period.[22][3] This stability reflected suburban expansion patterns, with public administration emerging as a notable sector contributing approximately 20% of jobs by the 2010s, though manufacturing and related industries continued to dominate local employment.[5] Diversification accelerated in the 2020s through targeted zoning reforms and land annexations aimed at attracting technology investments. In January 2025, the city secured an annexation agreement with the adjacent town to enable infrastructure upgrades and zoning modifications for expanded industrial uses.[23] This was followed by the May 2025 annexation of 562 acres, rezoned under a new "Technology Campus District" to accommodate high-tech facilities, marking a shift from traditional manufacturing toward data-intensive operations.[24] Additional annexations in July and August 2025 added over 700 acres, bringing the total developed land for the initiative to 1,315 acres by mid-year, with provisions for further parcels to support scalable industrial parks.[25][26] The pinnacle of these efforts materialized in 2025 with approvals for an $8 billion data center campus by Vantage Data Centers on approximately 1,900 acres, designed to host AI operations for tenants including OpenAI and Oracle, with a potential value escalation to $15 billion including ancillary infrastructure.[27][28] The Port Washington Common Council unanimously approved the development agreement in August 2025, followed by Plan Commission endorsement of a tax incremental district (TID) in October to fund site preparations, projecting substantial tax revenue growth from the project's phased construction of up to four data halls.[29][30] Officials anticipate hundreds of high-wage construction and operational jobs, bolstering long-term economic resilience amid manufacturing's persistence.[31] Supporting infrastructure included a proposed $1.4 billion high-voltage transmission line announced in October 2025 to deliver reliable power for the campus's 3.5 gigawatt demand, addressing grid capacity needs through partnerships with utilities.[32] These developments, grounded in city council records and economic projections, underscore a data-driven pivot toward tech-enabled growth, with environmental stipulations for clean energy integration to mitigate resource strains.[33]Geography

Location, topography, and natural features

Port Washington occupies the western shore of Lake Michigan in Ozaukee County, southeastern Wisconsin, at approximately 43°23′N 87°52′W. The city center lies about 25 miles north of downtown Milwaukee along the lakeshore.[13] [34] The local terrain features low-lying coastal areas near the lake, with elevations averaging around 600 feet above sea level in the immediate vicinity of the city, though bluffs rise to 70–140 feet in height along segments of the shoreline. These bluffs, composed of erodible soils and clays, contribute to ongoing shoreline recession influenced by wave action and fluctuating lake levels. Sandy beaches and occasional dunes border the water, interspersed with natural creek outlets.[35] [36] [37] Sauk Creek, a prominent natural waterway, traverses the northern part of the city, flowing southward over exposed limestone bedrock ledges before emptying into Lake Michigan; the creek's watershed supports diverse riparian habitats within the 27-acre Sauk Creek Nature Preserve. Underlying geology includes dolomite and limestone formations, which have shaped the landscape through karst features and historically facilitated resource extraction, though the area's thin soils over bedrock limit certain agricultural uses. The natural harbor configuration, with depths ranging from 6–10 feet near shore to 28–35 feet offshore prior to dredging, originally enhanced the site's viability for maritime activities before engineered breakwaters exceeding 4,700 feet in length were constructed.[38] [39] [40]Climate and weather patterns

Port Washington experiences a humid continental climate (Köppen classification Dfa), featuring cold, snowy winters; warm, humid summers; and transitional spring and fall seasons with variable conditions. The city's location along Lake Michigan's western shore introduces lake-effect influences, which moderate daily temperature extremes by absorbing heat in summer and releasing it in winter, while also enhancing snowfall during northerly or easterly winds over the relatively warm lake surface. This results in slightly milder winters and cooler summers compared to inland areas of southeastern Wisconsin, though overall variability remains high due to continental air masses.[34][41] Historical records indicate average July highs of 79°F (26°C) and January lows of 17°F (-8°C), with an annual mean temperature around 47°F (8°C). Precipitation totals approximately 34 inches annually, distributed fairly evenly but peaking in June at 3.4 inches of rainfall; snowfall averages 43 inches per year, concentrated from December to March and augmented by lake-effect events that can produce bands of heavy snow. Extreme temperatures have reached highs near 100°F during summer heat waves and lows below 0°F in winter cold snaps, though lake proximity limits record deviations relative to non-coastal sites.[34][42] Notable weather events include the October 1–2, 2019, storm, which delivered 2–5 inches of rain across Ozaukee County, causing flash flooding in low-lying areas of Port Washington due to saturated soils and poor drainage. Such events underscore the region's vulnerability to intense short-duration rainfall, though long-term patterns show no statistically significant deviation from historical norms in precipitation intensity.[43]Demographics

Historical population changes

The population of Port Washington grew steadily from its early settlement phase, reflecting influxes of immigrants and economic opportunities tied to its Lake Michigan harbor. The 1850 U.S. Census recorded 721 residents, primarily early Yankee and British Isles settlers supplemented by initial waves of German-speaking immigrants arriving in the late 1840s.[44][14] By 1860, the count reached 1,632, driven by continued German immigration that formed the ethnic core of the community, with many establishing businesses and farms.[45] Growth moderated in subsequent decades amid industrial fluctuations, but accelerated after 1940 with suburban migration from nearby Milwaukee, as families sought waterfront amenities and proximity to urban jobs. Decennial census figures illustrate this trajectory:| Year | Population | Percent Change |

|---|---|---|

| 1850 | 721 | — |

| 1860 | 1,632 | +126.4% |

| 1870 | 2,575 | +57.8% |

| 1880 | 2,773 | +7.7% |

| 1890 | 2,620 | -5.5% |

| 1900 | 2,913 | +11.2% |

| 1910 | 3,113 | +6.9% |

| 1920 | 3,355 | +7.8% |

| 1930 | 3,415 | +1.8% |

| 1940 | 3,745 | +9.7% |

| 1950 | 4,643 | +24.0% |

| 1960 | 6,134 | +32.2% |

| 1970 | 7,468 | +21.7% |

| 1980 | 9,727 | +30.3% |

| 1990 | 9,990 | +2.7% |

| 2000 | 10,467 | +4.7% |

| 2010 | 11,250 | +7.5% |

2020 census and recent estimates

The 2020 United States Census enumerated a population of 12,020 in Port Washington, Wisconsin. The racial and ethnic composition consisted primarily of White individuals, who made up 91.4% of the population, followed by Hispanic or Latino residents at 5.6%, Black or African American at 1.5%, Asian at 2.4%, and those identifying with two or more races at 3.0%; other groups such as American Indian and Alaska Native accounted for 0.1%. The median age was 42.3 years, with an average household size of 2.3 persons. Economic indicators from the American Community Survey (2019-2023) showed a poverty rate of 6.9%, per capita income of $57,684, and median household income of $81,582. Housing data indicated 5,433 total units, with an owner-occupied homeownership rate of 62.3%.| Demographic Category | Percentage/Value (2020 Census/ACS 2019-2023) |

|---|---|

| Total Population | 12,020 |

| White alone | 91.4% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 5.6% |

| Black or African American | 1.5% |

| Asian | 2.4% |

| Median Age | 42.3 years |

| Average Household Size | 2.3 |

| Poverty Rate | 6.9% |

| Per Capita Income | $57,684 |

| Homeownership Rate | 62.3% |

Government and Politics

Local municipal structure

Port Washington employs a mayor-council form of government supplemented by a professional city administrator to handle daily operations, promoting operational efficiency while preserving elected oversight for accountability.[50][51] The Common Council consists of the mayor, elected at-large, and seven alderpersons representing distinct wards, all serving two-year terms with staggered elections to ensure continuity.[50] Alderpersons from odd-numbered districts are elected in odd-numbered years during the spring election, while those from even-numbered districts are elected in even-numbered years.[50] The council holds legislative authority, including adopting the annual budget, levying property taxes via a formal process that sets the mill rate based on assessed valuations and required expenditures, and appropriating funds for city services.[50] It appoints the city administrator as the chief executive officer, who manages administrative departments such as police, fire, public works, and planning, reporting back to the council for policy alignment and performance evaluation.[50] Council meetings occur biweekly on the first and third Tuesdays, except in July, allowing for regular review of departmental reports and ordinance enactments to maintain fiscal and operational accountability.[52] In 2025, the council advanced zoning code revisions through the Planning and Development Department, including Ordinance No. 2025-15 adopted on August 19 for amendments to land use chapters and draft updates released in October to streamline approvals, align with the comprehensive plan, and facilitate balanced development while preserving community standards.[53][54]State and federal representation

Port Washington is represented in the Wisconsin State Senate by District 8, which encompasses northern Ozaukee County including the city as its core urban center, along with portions of Washington and Milwaukee counties, following the 2023 legislative redistricting enacted for the 2024 elections.[55] The current senator is Jodi Habush Sinykin (Democrat), who assumed office on January 6, 2025, after defeating incumbent Duey Stroebel (Republican) in the November 2024 general election in a competitive race reflecting suburban dynamics near Milwaukee.[55] In the State Assembly, the city falls within District 22, covering eastern Ozaukee County communities such as Port Washington, Cedarburg, and Grafton under the same 2023 maps.[56] Representative Paul Melotik (Republican) holds the seat, having won re-election in 2024.[57] At the federal level, Port Washington lies in Wisconsin's 6th congressional district, which includes most of eastern Wisconsin outside the Milwaukee urban core, based on boundaries from the 2020 census redistricting process. U.S. Representative Glenn Grothman (Republican) has represented the district since 2015 and was re-elected in 2024 for his sixth term.[58] Ozaukee County's representation has historically aligned with its conservative leanings, with Republican dominance in the area since the 1970s, though district-wide results can vary due to inclusions of adjacent suburban or urban precincts; minimal boundary shifts in recent redistrictings have preserved Port Washington's position as a key Republican-leaning anchor within these districts.Electoral trends and key policy debates

In presidential elections, Port Washington aligns with Ozaukee County's strong Republican preference, with voters supporting Republican candidates at margins exceeding 15 percentage points in recent cycles. In 2020, Ozaukee County gave 58.2% of its vote to Donald Trump over Joe Biden's 40.4%, reflecting a 17.8-point Republican edge.[59] This pattern persisted from 2016, when the county backed Trump with 60.1% against Hillary Clinton's 35.5%, yielding a 24.6-point margin.[60] Such outcomes position Ozaukee among Wisconsin's reliably Republican suburban counties, consistently delivering over 60% for GOP presidential nominees since 2000.[61] Voter participation in the area surpasses state norms, driven by high engagement in general elections. Ozaukee County's turnout reached 94.6% of registered voters in November 2024, far exceeding Wisconsin's statewide rate of approximately 76%.[62] Local turnout for spring elections, such as the April 2025 Common Council races, typically hovers around 20-30% of eligible voters but influences policy on municipal growth.[63] Common Council elections, held in non-partisan spring cycles, often hinge on development positions rather than national partisanship. In the 2025 District 3 race, incumbent Michael Gasper, a civil engineer advocating for infrastructure expansion, secured reelection with 62.3% against challenger Billy Schwalbe's 37.7%, amid debates over accommodating population growth.[64] A central policy contention involves balancing economic expansion with resource constraints, exemplified by the $8 billion AI data center project approved by the council in August 2025. Supporters emphasize its potential for thousands of construction and operational jobs, tax revenue, and diversification from manufacturing.[65] Opponents, including nearby residents, cite risks to the local power grid, water supply, and Lake Michigan watershed, with public hearings in October 2025 drawing record opposition.[66][67] These debates underscore tensions between pro-growth incumbents and skeptics favoring measured development to preserve quality of life.[68]Economy

Traditional industries and manufacturing base

Port Washington's traditional economy centered on resource extraction and early manufacturing, with limestone quarrying and lime production playing a pivotal role from the mid-19th century. The first lime kiln in the vicinity was constructed in 1846 by Timothy Higgins, leveraging local dolomite deposits to produce high-quality lime for mortar and plaster via wood-fired stone kilns.[69] By the late 19th century, operations like the Lake Shore Stone Company quarry supplied building stone for local structures, including St. Mary's Roman Catholic Church, while also firing lime in on-site kilns; statewide, Wisconsin's lime output exceeded one million barrels annually during this period, with Ozaukee County facilities contributing significantly until demand waned post-World War I.[70] [11] These industries employed dozens in quarrying and kiln operations, forming the backbone of the settlement's growth before mechanization and shifting markets reduced their dominance by the 1920s.[71] , Kleen Test Products Corporation in consumer goods manufacturing (250-499 employees), and Kickhaefer Manufacturing Company in metal stamping (250-499 employees), alongside public sector roles at Ozaukee County offices (500-999 employees).[5] Tourism, supported by the city's harbor and waterfront amenities, contributes seasonal jobs in hospitality and retail, though it ranks below core manufacturing and service sectors in employment volume.[81]| Sector | Employment (2023) |

|---|---|

| Manufacturing | 1,547 |

| Health Care & Social Assistance | 811 |

| Retail Trade | 711 |

Impacts of technological and infrastructural developments

The approval of the Vantage Data Centers campus in August 2025 marks a pivotal infrastructural development, featuring four data center buildings on a 672-acre site with over 2.5 million square feet of space and capacity approaching 1 gigawatt for artificial intelligence workloads.[82][83] This $8-15 billion project, integrated into the Stargate initiative by OpenAI and Oracle, commits to zero-emission energy sources and water-positive operations, with construction slated to commence imminently and conclude by 2028.[84][85] Economic forecasts from the developers and city officials project over 4,000 skilled construction jobs during the build phase, predominantly sourced locally, alongside approximately 1,000 long-term operational positions.[86] The initiative is anticipated to elevate the city's property valuation by up to $120 million, generating substantial annual property tax increments to fund public infrastructure enhancements, including $175 million in water, wastewater, and roadway expansions.[30][87] These developments are expected to yield multiplier effects, spurring demand for housing, commercial services, and ancillary industries through sustained capital influx and workforce influx, consistent with patterns observed in comparable large-scale data center deployments that amplify regional GDP via indirect employment and supply chain activity.[88] A proposed $1.4 billion high-voltage transmission line further supports scalability, ensuring power reliability for the campus's energy-intensive operations without immediate residential rate hikes.[32]Education

K-12 public education system

The Port Washington-Saukville School District serves as the primary provider of K-12 public education for Port Washington and adjacent Saukville, operating three elementary schools (Dunwiddie Elementary, Lincoln Elementary, and Thomas Jefferson Elementary), one middle school (Port Washington Middle School), and one high school (Port Washington High School).[89][90] The district enrolls approximately 2,519 students with a student-teacher ratio of 14:1 and maintains facilities including a recently renovated high school featuring state-of-the-art resources.[90][91] Performance metrics indicate strong outcomes relative to state benchmarks. The district's four-year adjusted cohort graduation rate is 98%, exceeding Wisconsin's statewide rate of 91.1% for the class of 2023-24.[91][92] On state assessments, 51% of students achieve proficiency in mathematics and 55% in reading, rates above the state averages of approximately 34% and 36%, respectively, for recent years.[91] The district earned an overall accountability score placing it in the top 44% of Wisconsin districts for the 2023-24 school year, based on factors including achievement, growth, chronic absenteeism, and graduation.[93] Per-pupil spending in the district totals $14,215, below the state median of $17,007 but aligned with operational needs for instruction, support services, and facilities maintenance.[94] Vocational offerings at Port Washington High School emphasize technical skills relevant to the area's manufacturing sector, including courses in wood manufacturing, building construction, computer-aided design, and industrial cooperative education programs that provide hands-on experience and industry partnerships.[95][96] These initiatives, such as collaborations with local firms like GenMet and Charter Steel, aim to address skilled trades shortages by integrating real-world manufacturing training into the curriculum.[96][97]Libraries and lifelong learning resources

The W.J. Niederkorn Library, located at 316 West Grand Avenue, serves as the central public library for Port Washington and surrounding areas, maintaining a collection of 54,784 physical volumes while providing access to over 3 million items through membership in the Monarch Library System.[98][99] Its annual circulation reached 263,134 transactions as of recent reporting, supporting a service population of approximately 17,730 residents that includes the City of Port Washington, Town of Port Washington, Fredonia, and Belgium.[98][100] This equates to roughly 14.8 circulations per capita, indicating robust usage relative to population size.[98][100] The library offers programs tailored for adult learners, such as role-playing game sessions for adults, contributing to a typical yearly total of 6,000 attendees across children and adult events.[99][101] Digital resources, including the Wisconsin Digital Library for e-books and streaming services like Kanopy, supplement physical holdings and enable remote access to educational materials.[101] Complementing library services, the Adult Literacy Center of Ozaukee County delivers personalized one-on-one tutoring for adults in the region, focusing on English as a Second Language, basic education in language arts and mathematics, GED preparation, college readiness, and U.S. citizenship instruction.[102] These offerings, available since at least 2017 through partnerships like United Way Northern Ozaukee, target skill-building for personal and professional development among Port Washington-area residents.[102]Proximity to higher education