Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

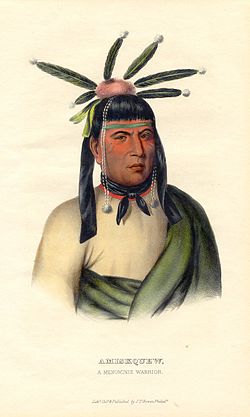

Menominee

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

The Menominee (/məˈnɒmɪni/ ⓘ mə-NOM-in-ee; Menominee: omǣqnomenēwak meaning "Menominee People",[2] also spelled Menomini, derived from the Ojibwe language word for "Wild Rice People"; known as Mamaceqtaw, "the people", in the Menominee language) are a federally recognized tribe of Native Americans officially known as the Menominee Indian Tribe of Wisconsin. Their land base is the Menominee Indian Reservation in Wisconsin. Their historic territory originally included an estimated 10 million acres (40,000 km2) in present-day Wisconsin and the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. The tribe currently has about 8,700 members.

Federal recognition of the tribe was terminated in the 1960s under policy of the time which stressed assimilation. During that period, they brought what has become a landmark case in Indian law to the United States Supreme Court, in Menominee Tribe v. United States (1968), to protect their treaty hunting and fishing rights. The Wisconsin Supreme Court and the United States Court of Claims had drawn opposing conclusions about the effect of the termination on Menominee hunting and fishing rights on their former reservation land. The U.S. Supreme Court determined that the tribe had not lost traditional hunting and fishing rights as a result of termination, as Congress had not clearly ended these in its legislation.

The tribe regained federal recognition in 1973 by an act of Congress, re-establishing its reservation in 1975. It operates under a written constitution establishing an elected government. The tribe took over tribal government and administration from the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) in 1979.

Overview

[edit]

The Menominee are part of the Algonquian language family of North America, made up of several tribes now located around the Great Lakes and many other tribes based along the Atlantic coast. They are one of the historical tribes of present-day upper Michigan and Wisconsin; they occupied a territory of about 10 million acres (40,000 km2) in the period of European colonization.[3] They are believed to have been well-settled in that territory for more than 1,000 years. By some accounts, they are descended from the Old Copper Culture people and other indigenous peoples who had been in this area for 10,000 years.[4]

Menominee oral history states that they have always been here[5] and believe they are Kiash Matchitiwuk (kee ahsh mah che te wuck) which is "Ancient Ones". Their reservation is located 60 miles west of the site of their Creation, according to their tradition. They arose where the Menominee River enters Green Bay of Lake Michigan, where the city of Marinette, Wisconsin, has since developed.[4]

Their name for themselves is Mamaceqtaw, meaning "the people". The name "Menominee" is not their autonym. It was adopted by Europeans from the Ojibwe people, another Algonquian tribe whom they encountered first as they moved west and who told them of the Menominee. The Ojibwe name for the tribe was manoominii, meaning "wild rice people", as they cultivated wild rice as one of their most important food staples.[6]

Historically, the Menominee were known to be a peaceful, friendly and welcoming nation, who had a reputation for getting along with other tribes. When the Oneota culture arose in southern Wisconsin between AD 800 and 900, the Menominee shared the forests and waters with them.

The Menominee are a Northeastern Woodlands tribe. They were initially encountered by European explorers in Wisconsin in the mid-17th century during the colonial era, and had extended interaction with them during later periods in North America.[7] During this period they lived in numerous villages which the French visited for fur trading. The anthropologist James Mooney in 1928 estimated that the tribe's number in 1650 was 3,000 persons.[8]

The early French explorers and traders referred to the people as "folles avoines" (wild oats), referring to the wild rice which they cultivated and gathered as one of their staple foods. The Menominee have traditionally subsisted on a wide variety of plants and animals, with wild rice and sturgeon being two of the most important. Wild rice has a special importance to the tribe as their staple grain, while the sturgeon has a mythological importance and is often referred to as the "father" of the Menominee.[9] Feasts are still held annually at which each of these is served.[5]

Menominee customs are quite similar to those of the Chippewa (Ojibwa), another Algonquian people. Their language has a closer affinity to those of the Meskwaki and Kickapoo tribes. All four spoke Anishinaabe languages, part of the Algonquian family.

The five principal Menominee clans are the Bear, the Eagle, the Wolf, the Crane, and the Moose. Each has traditional responsibilities within the tribe. With a patrilineal kinship system, traditional Menominee believe that children derive their social status from their fathers, and are born "into" their father's clan. Members of the same clan are considered relatives, so must choose marriage partners from outside their clan.[10] Ethnologist James Mooney wrote an article on the Menominee which appeared in Catholic Encyclopedia (1913), incorrectly reporting that their descent and inheritance proceeds through the female line. Such a matrilineal kinship system is common among many other Native American peoples, including other Algonquian tribes.

Culture

[edit]

Traditional Menominee spiritual culture includes rites of passage for youth at puberty. Ceremonies involve fasting for multiple days and living in a small isolated wigwam. As part of this transition, youth meet individually with Elders for interpretation of their dreams, and to receive information about what adult responsibilities they will begin to take on following their rites of passage.[11]

Ethnobotany

[edit]Traditional Menominee diets include local foods such as Allium tricoccum (ramps, or wild garlic).[12] Boiled, sliced potatoes of Sagittaria cuneata are traditionally strung together and dried for winter use.[13] Uvularia grandiflora (bellwort) has historically been used to treat pain and swellings.[14] Pseudognaphalium obtusifolium, ssp obtusifolium (rabbit tobacco) is also used medicinally. Taenidia integerrima (a member of the parsely family) is taken as a root infusion for pulmonary troubles, and as chew, the steeped root, for 'bronchial affections';[15] it is also used as a companion herb in other remedies because of its pleasant smell.[16] The inner bark of Abies balsamea is used as a seasoner for medicines, taking an infusion of the inner bark for chest pain and using the liquid balsam pressed from the trunk for colds and pulmonary troubles. The inner bark is used as a poultice for unspecified illnesses.[17] Gum from plant blisters is also applied to sores.[18]

History

[edit]The tribe originally occupied a large territory of 10 million acres (40,000 km2) extending from Wisconsin to the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. Historic references include one by Father Frederic Baraga, a missionary priest in Michigan, who in his 1878 dictionary wrote:

Mishinimakinago; pl.-g.—This name is given to some strange Indians (according to the sayings of the Otchipwes [Ojibwe]), who are rowing through the woods, and who are sometimes heard shooting, but never seen. And from this word, the name of the village of Mackinac, or Michillimackinac, is derived.[19]

Maehkaenah is the Menominee word for turtle. In his The Indian Tribes of North America (1952), John Reed Swanton recorded under the "Wisconsin" section: "Menominee," a band named "Misi'nimäk Kimiko Wini'niwuk, 'Michilimackinac People,' near the old fort at Mackinac, Mich."[8] Michillimackinac is also spelled as Mishinimakinago, Mǐshǐma‛kǐnung, Mi-shi-ne-macki naw-go, Missilimakinak, Teiodondoraghie.

The Menominee are descendants of the Late Woodland Indians who inhabited the lands once occupied by Hopewell Indians, the earliest human inhabitants of the Lake Michigan region. As the Hopewell culture declined, circa A.D. 800, the Lake Michigan region eventually became home to Late Woodland Indians.

Early fur traders, coureur-de-bois, and explorers from France encountered their descendants: the Menominee, Ojibwe, Odawa, Potawatomi, Sauk, Meskwaki, Ho-Chunk and Miami. It is believed that the French explorer Jean Nicolet was the first non-Native American to reach Lake Michigan in 1634 or 1638.[20]

First European encounter

[edit]

In 1634, the Menominee and Ho-Chunk people (along with a band of Potawatomi who had recently moved into Wisconsin) witnessed the French explorer Jean Nicolet's approach and landing. Red Banks, near the present-day city of Green Bay, Wisconsin, later developed in this area. Nicolet, looking for a Northwest Passage to China, hoped to find and impress the Chinese. As the canoe approached the shore, Nicolet put on a silk Chinese ceremonial robe, stood up in the middle of the canoe and shot off two pistols.

Pierre François Xavier de Charlevoix, a French Catholic clergyman, professor, historian, author and explorer, kept a detailed journal of his travels through Wisconsin and Louisiana. In 1721 he came upon the Menominee, whom he referred to as Malhomines ("peuples d'avoines" or Wild Oat Indians), which the French had adapted from an Ojibwe term:

After we had advanced five or six leagues, we found ourselves abreast of a little island, which lies near the western side of the bay, and which concealed from our view, the mouth of a river, on which stands the village of the Malhomines Indians, called by our French "peuples d'avoines" or Wild Oat Indians, probably from their living chiefly on this sort of grain. The whole nation consists only of this village, and that too not very numerous. 'Tis really great pity, they being the finest and handsomest men in all Canada. They are even of a larger stature than the Potawatomi. I have been assured that they had the same original and nearly the same languages with the Noquets, and the Indians at the Falls.[21]

19th century

[edit]

Initially neutral during the War of 1812, the Menominee later became allied with the British and Canadians, whom they helped defeat American forces trying to recapture Fort Mackinac in the Battle of Mackinac Island. During the ensuing decades, the Menominee were pressured by encroachment of new European-American settlers in the area. Settlers first arrived in Michigan, where lumbering on the Upper Peninsula and resource extraction attracted workers. By mid-century, encroachment by new settlers was increasing. In the 1820s, the Menominee were approached by representatives of the Christianized Stockbridge-Munsee Indians from New York to share or cede some of their land for their use.

The Menominee gradually sold much of their lands in Michigan and Wisconsin to the U.S. government through seven treaties from 1821 to 1848, first ceding their lands in Michigan. The US government wanted to move them to the far west in the period when Wisconsin was organizing for statehood, to extinguish all Native American land claims. Chief Oshkosh went to look at the proposed site on the Crow River and rejected the offered land, saying their current land was better for hunting and game. The Menominee retained lands near the Wolf River in what became their current reservation.[22] The tribe originated in the Wisconsin and are living in their traditional homelands.[5]

Modern-era conflicts

[edit]Logging

[edit]The Menominee have traditionally practiced logging in a sustainable manner. In 1905, a tornado swept through the reservation, downing a massive amount of timber. Because the Menominee-owned sawmills could not harvest all the downed timber before it decomposed, the United States Forest Service became involved in managing their forest. Despite the desire of the tribe and Senator Robert M. La Follette, Sr. for sustainable yield policy, the Forest Service conducted clear-cutting on reservation lands until 1926, cutting 70 percent of the salable timber.

The Department of the Interior regained control of the territory, as it holds the reservation in trust for the Menominee. During the next dozen years, it reduced the cutting of salable timber to 30 percent, which allowed the forest to regenerate. In 1934, the Menominee filed suit in the United States Court of Claims against the Forest Service, saying that its policy had heavily damaged their resource. The court agreed and settled the claim finally in 1952, awarding the Menominee $8.5 million.[23]

20th-century termination era

[edit]

The Menominee were among the Native Americans who participated as soldiers in World War II with other United States citizens.

During the 1950s, federal Indian policy envisioned termination of the "special relationship" between the United States government and those tribes considered "ready for assimilation" to mainstream culture. The Menominee were identified for termination, which would end their status as a sovereign nation. At the time, the Klamath people in Oregon were the only other tribal group identified for termination. The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) believed the Menominee were sufficiently economically self-reliant on their timber industry to be successful independent of federal assistance and oversight. Before termination, they were one of the wealthiest American Indian tribes.

In 1954, Congress passed a law which phased out the Menominee reservation, effectively terminating its tribal status on April 30, 1961. Commonly held tribal property was transferred to a corporation, Menominee Enterprises, Inc. (MEI). It had a complicated structure and two trusts, one of which, First Wisconsin Trust Company, was appointed by the BIA. First Wisconsin Trust Company always voted its shares as a block, and essentially could control the management operations of MEI.[23]

At the request of the Menominee, the state organized the former reservation as a new county, so they could maintain some coherence. The tribe was expected to provide county government functions but it became a colony of the state.[24]

The change resulted in diminished standards of living for the members of the tribe; officials had to close the hospital and some schools in order to cover costs of the conversion: to provide their own services or contract for them as a county. Menominee County was the poorest and least populated Wisconsin county during this time, and termination adversely affected the region. Tribal crafts and produce alone could not sustain the community. As the tax base lacked industry, the Menominee could not fund basic services. MEI funds, which totaled $10 million in 1954, dwindled to $300,000 by 1964.[25] Struggling to manage financially, the white-dominated MEI proposed in 1967 to raise money by selling off former tribal lands to non-Native Americans, which resulted in a fierce backlash among the Menominee.

It was a period of Indian activism, and community members began an organizing campaign to regain political sovereignty as the Menominee Tribe. Activists included Ada Deer, an organizer who would later become an advocate for Native Americans at the federal level as Assistant Secretary of Indian Affairs (1993–1997). In 1970 the activists formed a group called the Determination of Rights and Unity for Menominee Stockholders (DRUMS). They blocked the proposed sale of tribal land by MEI to non-Indian developers, and successfully gained control of the MEI board of directors. They also persuaded Congress to restore their status as a federally recognized sovereign tribe by legislation.[26][27]

At the same time, President Richard Nixon encouraged a federal policy to increase self-government among Indian tribes, in addition to increasing education opportunities and religious protection. He signed the bill for federal recognition of the Menominee Tribe of Wisconsin on December 22, 1973. The sovereign tribe started the work of reorganizing the reservation, which they re-established in 1975. Tribal members wrote and ratified a tribal constitution in 1976, and elected a new tribal government, which took over from BIA officials in 1979.

Menominee Tribe v. United States (1968)

[edit]During the period of termination, when the Menominee individually were subject to state law, in 1963 three members of the tribe were charged with violating Wisconsin's hunting and fishing laws on what had formerly been their reservation land for more than 100 years. The tribal members were acquitted. When the state appealed the decision, the Wisconsin Supreme Court held that the Menominee tribe no longer had hunting and fishing rights due to the termination act of Congress in 1954.

Due to the state court's ruling, the tribe sued the United States for compensation for the value of the hunting and fishing rights in the U.S. Court of Claims, in Menominee Tribe v. United States (1968). The Court ruled that tribal members still had hunting and fishing rights, and that Congress had not abrogated those rights. The opposite rulings by the state and federal courts brought the issue to the United States Supreme Court.

In 1968 the Supreme Court held that the tribe retained its hunting and fishing rights under the treaties involved, and the rights were not lost after federal recognition was ended by the Menominee Termination Act, as Congress had not clearly removed those rights in its legislation. This has been a landmark case in Indian law, helping preserve Native American hunting and fishing rights.

Anaem Omot

[edit]The site Anaem Omot along the banks of the Menominee River is considered the sacred home of the Menominee Nation, with artifacts there dating as far back as 8,000 B.C.[28] For a 600-year period from A.D. 1000 to 1600, the site was intensively farmed and has been a special area of study by archaeologists as the most intact pre-European farming site in eastern North America.[28] In 2015, an open pit gold mine was proposed that would impact the site, and the Menominee and their supporters have been fighting to stop the mine construction. In June 2023, the National Park Service added the site to the National Register of Historic Places following a contentious multi-year nomination process that was supported by both states of Michigan and Wisconsin; it was opposed by the gold company and some local Upper Peninsula lawmakers.[29] Although the NRHP listing affords "zero protection" to the land, it is a stepping stone towards applying for a higher level of land conservation that would offer legal protections.[30]

Current tribal activities

[edit]The nation has a notable forestry resource and manages a timber program.[31] In an 1870 assessment of their lands, which totaled roughly 235,000 acres (950 km2), they counted 1.3 billion standing board feet (3.1 million cubic metres) of timber. As of 2002[update] that has increased to 1.7 billion board feet (4.0 million m3). In the intervening years, they have harvested more than 2.25 billion board feet (5.3 million m3).[32] In 1994, the Menominee became the first forest management enterprise in the United States certified by the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC.org).[33][34]

Since June 5, 1987, the tribe has owned and operated a Las Vegas-style gaming casino, associated with bingo games and a hotel. The complex provides employment to numerous Menominee; approximately 79 percent of the Menominee Casino-Bingo-Hotel's 500 employees are ethnic Menominee or are spouses of Menominee.[35][better source needed]

Menominee Indian Reservation

[edit]

The Menominee Indian Reservation is located in northeastern Wisconsin. For the most part, it is conterminous with Menominee County and the town of Menominee, which were established after termination of the tribe in 1961 under contemporary federal policy whose goal was assimilation. The tribe regained its federally recognized status and reservation in 1975.

The reservation was created in a treaty with the United States signed on May 12, 1854, in which the Menominee relinquished all claims to the lands held by them under previous treaties, and were assigned 432 square miles (1,120 km2) on the Wolf River in present-day Wisconsin. An additional treaty, which they signed on February 11, 1856, carved out the southwestern corner of this area to create a separate reservation for the Stockbridge and Lenape (Munsee) tribes, who had reached the area as refugees from New York state. The latter two tribes have the federally recognized joint Stockbridge-Munsee Community.

After the tribe had regained federal recognition in 1973, it essentially restored the reservation to its historic boundaries in 1975. Many small pockets of territory within the county (and its geographically equivalent town) are not considered as part of the reservation. These amount to 1.14% of the county's area, so the reservation is essentially 98.86% of the county's area. The largest of these pockets is in the western part of the community of Keshena, Wisconsin. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the combined Menominee reservation and off-reservation trust land have a total area of 362.8 square miles (939.6 km2), of which 355.5 square miles (920.7 km2) is land and 7.3 square miles (18.9 km2) is water.[36]

The small non-reservation parts of the county are more densely populated than the reservation, with 1,223 (28.7%) of the county's 4,255 total population, as opposed to the reservation's 3,032 (71.3%) population in the 2020 census.[37][38]

The most populous communities are Legend Lake and Keshena. Since the late 20th century, the members of the reservation have operated a number of gambling facilities in these communities as a source of revenue. They speak English as well as their traditional Menominee language, one of the Algonquian languages.[39] Current population of the tribe is about 8,700.

Communities

[edit]- Keshena (most, population 1,268)

- Legend Lake (most, population 1,525)

- Middle Village (part, population 281)

- Neopit (most, population 690)

- Zoar (most, population 98)

Government

[edit]The tribe operates according to a written constitution. It elects a tribal council and chairman.

The Menominee developed the College of Menominee Nation in 1993 and it was accredited in 1998. It includes a Sustainable Development Institute. Its goal is education to promote their ethic for living in balance on the land.[40] It is one of a number of tribal colleges and universities that have been developed since the early 1970s, and one of two in Wisconsin.

Notable Menominee

[edit]- Apesanahkwat – actor who starred in Babylon 5 and films

- Alaqua Cox - actress, Hawkeye & Echo

- Ada Deer – activist and Assistant Secretary for Indian Affairs, 1993–1997

- Billie Frechette – lover of 1930s serial bank robber John Dillinger

- Mitchell Oshkenaniew – advocate for sovereignty and recognition by federal government[41]

- Chief Oshkosh (1795–1858) – chief of Menominee during period of land cessions and restriction to reservation within Wisconsin

- Sheila Tousey – actress, Thunderheart (1992)

- Ingrid Washinawatok – Co-founder, Fund for the Four Directions, indigenous activist; killed in 1999 in Colombia by the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia

Notes

[edit]- ^ Brief History - About Us. The Menomonee Indian Tribe of Wisconsin.

- ^ Center for Menominee Language, Culture, and Art, Language Materials www.menomineelanguage.com/dictionaries-word-lists, Menominee Dictionary - English - Menominee Link (Archive) - Menominee, Menominee Person Pg. 144

- ^ History, Menominee Indian Tribe of Wisconsin

- ^ a b Boatman, John (1998). Wisconsin American Indian History and Culture. Dubuque, IA: Kendall/Hunt Publishing Co., p.37.

- ^ a b c "Menominee" Archived 2007-06-26 at the Wayback Machine, Indian Country, Milwaukee Public Museum

- ^ Campbell, Lyle (1997).American Indian Languages: The Historical Linguistics of Native America, Oxford: Oxford University Press, p.401, n.134

- ^ "Menominee Indian Tribe of Wisconsin. Who are We?". Archived from the original on 2011-10-14. Retrieved 2011-12-28.

- ^ a b Swanton, John R. (1952). Indian Tribes of North America. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. Reprinted by the Smithsonian Institution, 1974, 1979, 1984, pp. 250–256.

- ^ Ross, Norbert; Medin, Douglas; Cox, Douglass (2006). Culture and Resource Conflict: Why Meanings Matter. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. ISBN 978-0-87154-570-1.

- ^ "Menominee Clans depicted at UWSP", Pointer Alumnus, University of Wisconsin – Steven Point, Spring 2003, pp. 1 and 5, accessed 28 August 2012

- ^ "Menominee Culture", Indian Country Wisconsin, Milwaukee Public Museum

- ^ Smith, Huron H. 1923 "Ethnobotany of the Menomini Indians". Bulletin of the Public Museum of the City of Milwaukee 4:1-174 (p. 69)

- ^ Smith, Huron H. 1923 "Ethnobotany of the Menomini Indians". Bulletin of the Public Museum of the City of Milwaukee 4:1-174 (p. 61)

- ^ Smith, Huron H. 1923 "Ethnobotany of the Menomini Indians". Bulletin of the Public Museum of the City of Milwaukee 4:1-174 (p. 41)

- ^ Smith, Huron H., 1923, Ethnobotany of the Menomini Indians, Bulletin of the Public Museum of the City of Milwaukee 4:1-174, page 56

- ^ Smith, Huron H., 1928, Ethnobotany of the Meskwaki Indians, Bulletin of the Public Museum of the City of Milwaukee 4:175-326, page 250

- ^ Smith, Huron H., 1923, Ethnobotany of the Menomini Indians, Bulletin of the Public Museum of the City of Milwaukee 4:1-174, page 45

- ^ Densmore, Francis, 1932, Menominee Music, SI-BAE Bulletin #102, page 132

- ^ Baraga, Frederic (1878). A Dictionary of the Otchipwe Language. Montreal: Beauchemin & Valois, v. 2, p. 248.

- ^ Bogue, Margaret Beattie (1985). Around the Shores of Lake Michigan: A Guide to Historic Sites, pp. 7–13. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 0-299-10004-9.

- ^ Charlevoix., Pierre Francois Xavier de (1928). Louise Phelps Kellogg, Ph.D. (ed.). Journal of a Voyage to North America in Two Volumes (Report). The Caxton Club.

- ^ The Menominee Tribe of Indians v. United States, 95 Ct.Cl. 232 (Ct.Cl., 1941).

- ^ a b Patty Loew (2001). Indian Nations of Wisconsin: Histories of Endurance and Renewal. Madison: Wisconsin Historical Society Press, pp. 31–34.

- ^ Nancy O. Lurie (1972.) "Menominee Termination: From Reservation to Colony," Human Organization, 31: 257-269

- ^ Tiller, Veronica. Tiller's Guide to Indian Country: Economic Profiles of American Indian Reservations, Bowarrow Publishing Company, 1996. ISBN 1-885931-01-8.

- ^ Indian Country Wisconsin Archived 2007-06-26 at the Wayback Machine, Milwaukee Public Museum, accessed 30 June 2008.

- ^ Nancy O. Lurie, (1971) "Menominee Termination," Indian Historian, 4(4): 31–43.

- ^ a b Lidz, Franz (June 7, 2025). "Farming Was Extensive in Ancient North America, Study Finds". The New York Times. Retrieved 2025-06-07.

- ^ Ellison, Garret (June 28, 2023). "National Register listing approved for Anaem Omot historic site". Michigan Live. Retrieved 2025-06-07.

- ^ Garret Ellison (February 14, 2023). "Anaem Omot: Michigan gold mine fights tribe over historic land". mLive.

- ^ Alan McQuillan, "American Indian Timber Management Policy: Its Evolution in the Context of U. S. Forest History," in Trusteeship in Change: Toward Tribal Autonomy in Resource Management, eds. R. L. Clow and I Sutton (University Press of Colorado, 2001): 73–102.

- ^ William McDonough and Michael Braungart, Cradle to Cradle; Remaking the Way We Make Things, New York: North Point Press, 2002, p. 88

- ^ Sustainable Management of Temperate Hardwood Forests: A Review of the Forest Management Practices of Menominee Tribal Enterprises, Inc. 1992. Scientific Certification Systems, Berkeley, CA.

- ^ Assessment of the Forest Management Practices of the Menominee Tribal Enterprises, Inc. 1994. Scientific Certification Systems, Berkeley, CA, and Smart Wood Certification Program. Sigurd Olson Environmental Institute, Northland College, Ashland, WI

- ^ About Us

- ^ "2020 Gazetteer Files". census.gov. US Census Bureau. Retrieved 13 July 2022.

- ^ "2020 Decennial Census: Menominee County, Wisconsin". data.census.gov. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved 13 July 2022.

- ^ "2020 Decennial Census: Menominee Reservation (reservation only)". data.census.gov. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved 13 July 2022.

- ^ Menominee Language and the Menominee Indian Tribe (Menomini, Mamaceqtaw)

- ^ "Sustainable Development Institute » Research Education Outreach", College of Menominee Nation

- ^ "The Struggle for Self-Determination", History of the Menominee Indians since 1854, Britannica Encyclopedia online

References

[edit]- Beck, David R. M. (2005). The Struggle for Self-Determination: History of the Menominee Indians Since 1854. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

- Boatman, John (1998). Wisconsin American Indian History and Culture. Dubuque, IA: Kendall/Hunt Publishing.

- Davis, Thomas (2000). Sustaining the Forest, the People, and the Spirit. Albany, N.Y.: State University of New York.

- Loew, Patty (2001). Indian Nations of Wisconsin: Histories of Endurance and Renewal. Madison: Wisconsin Historical Society Press.

- Nichols, Phebe Jewell (Mrs. Angus F. Lookaround). Oshkosh The Brave: Chief of the Menominees, and His Family. Menominee Indian Reservation, 1954.

- Skinner, Alanson (1921). Material culture of the Menomini. Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation. Retrieved 25 August 2012.

Further reading

[edit]- Nancy Lurie (1972), "Menominee Termination: From Reservation to Colony," Human Organization, 31: 257–269

- Nancy Lurie (1987), "Menominee Termination and Restoration," in Donald L. Fixico, ed., An Anthology of Western Great Lakes Indians History (Milwaukee: American Indian Studies Program): 439–478

External links

[edit]- Menominee Indian Tribe of Wisconsin

- Menominee Language Lessons

- The Menominee Clans Story at University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point

- Perey, "The Menominee Myth of the Flood – in Relation to Life Today", Anthropology.net

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- "Treaties between the United States and the Menominee", Menominee website

- "Menominee", Indian Country, Milwaukee Public Museum

- Mitchell A. Dodge papers on the Menominee Indian Tribe, MSS 1538 in the L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University

Menominee

View on GrokipediaThe Menominee, an Algonquian-speaking Native American tribe known as Mamaceqtaw or "the people," are indigenous to the Great Lakes region with a recorded presence in present-day Wisconsin, Michigan, and Illinois spanning over 10,000 years.[1][2] Their traditional territory originally encompassed approximately 10 million acres, centered around the Green Bay area and extending northward to the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, but was progressively reduced through seven treaties with the United States government in the 19th century, culminating in the establishment of a permanent 235,000-acre reservation along the Wolf River in northeastern Wisconsin in 1854.[1][2] The tribe's name derives from manōmin, the Ojibwe term for wild rice, which remains central to their sustenance, culture, and identity as the "Wild Rice People."[2] Organized into five matrilineal clans—Bear, Eagle, Wolf, Moose, and Crane—the Menominee maintain a rich oral tradition tracing their creation to the mouth of the Menominee River and emphasizing harmony with natural resources, including sustainable forestry practices on their reservation lands that have preserved over 219,000 acres of forest.[3][4] In the 20th century, the Menominee faced federal termination of their tribal status under the 1954 Menominee Termination Act, which dissolved their government and reservation into Menominee County, Wisconsin, leading to economic hardship for many members until restoration through the 1973 Menominee Restoration Act, which reinstated federal recognition and tribal sovereignty.[1][2] Today, the tribe numbers over 8,700 enrolled members, with fewer than half residing on the reservation in Keshena, and operates as a sovereign nation managing enterprises like timber production while preserving their language, spiritual practices, and historical ties to the land.[1][4]

Identity and Demographics

Etymology and Self-Identification

The Menominee people identify themselves as Mamaceqtaw, a term in their Algonquian language meaning "the people," emphasizing their self-conception as the original inhabitants of their ancestral territories in the Great Lakes region.[5] This autonym underscores a common Indigenous pattern of endonymic naming centered on communal identity rather than specific descriptors of subsistence or geography.[5] The exonym "Menominee" (also spelled Menomini) originated from neighboring Algonquian-speaking tribes, particularly the Ojibwe, who referred to them as manoominii or Omaeqnomenewak, translating to "wild rice people."[6] This designation highlights the tribe's traditional harvesting and cultivation of wild rice (Zizania palustris), a staple food source gathered from lakes and rivers in their pre-colonial domain spanning present-day Wisconsin, upper Michigan, and parts of Illinois. European explorers and settlers adopted the term from these intertribal references during the 17th and 18th centuries, applying it in treaties and records without regard for the people's preferred self-designation.[6] The name's persistence reflects broader historical dynamics of external labeling in colonial documentation, where Indigenous groups were often identified through the lens of neighboring peoples' languages and perceptions.[6]Population and Linguistic Status

The Menominee Indian Tribe of Wisconsin maintains an enrolled membership of approximately 8,700 individuals, with fewer than half residing on the tribe's reservation in northeastern Wisconsin due to constraints on employment and housing.[7][8] The reservation, encompassing Menominee County, supports a population where American Indians constitute about 78% of residents, reflecting the tribe's concentrated presence amid broader demographic shifts from off-reservation migration.[9] The Menominee language (Omaeqnomenew), an Algonquian tongue isolate within its branch, is critically endangered, with only one remaining fluent first-language speaker from an unbroken lineage and a handful of other elderly proficient users.[10][11] Historically spoken by over 2,000 prior to assimilation policies, its decline stems from federal boarding schools and cultural suppression, though revitalization initiatives— including immersion daycares, a dedicated language campus, and certification of 42 enrolled members as instructors—aim to foster second-language acquisition among youth.[12][11]Origins and Pre-Colonial Society

Traditional Origin Story

According to Menominee oral tradition, the tribe's origins involve the Great Spirit (Mashé Manido) creating various spirits, with the Good Spirit (Kishä Manido) transforming a bear into the first human at the mouth of the Menominee River, approximately 60 miles east of the current reservation. This bear-human then invited an eagle and a sturgeon to join in human form, establishing the foundational Bear, Eagle, and Sturgeon clans that form the basis of Menominee social structure. Additional clans, including Crane and Wolf, emerged during subsequent river journeys, expanding the phratry system to five principal divisions—Bear, Eagle, Wolf, Crane, and Moose—each with defined roles in governance, warfare, hunting, construction, and resource management.[13][3][14] The culture hero Manabush, depicted as a great rabbit born to the unmarried daughter of the grandmother figure Nokomis, further shaped the people's emergence and survival. Manabush gathered scattered human-animal descendants, taught practical skills such as hunting and plant use, introduced fire (stolen from guardians), provided tobacco through trickery against a giant, and founded the Grand Medicine Society to combat diseases sent by malevolent spirits. His feats, including slaying a water monster and establishing balanced cycles of day and night through contests with animals like the Saw-Whet Owl, reinforced communal practices and reverence for animal ancestors, particularly bears as progenitors.[13][15] Menominee tradition positions the tribe as the "Ancient Ones" (Kiash Matchitiwuk), indigenous to over 10 million acres in present-day Wisconsin and Upper Michigan for more than 10,000 years, with no migration narrative from elsewhere—unlike many neighboring Algonquian groups. This origin emphasizes continuous occupancy and clan interdependencies, where totemic animals symbolize enduring ties to the environment, informing rituals, leadership, and resource stewardship. Ethnographic accounts, drawn from elders and early recorders like W.J. Hoffman in 1890, preserve these elements, though variations exist across tellings.[3][13][15]Archaeological and Subsistence Evidence

Archaeological investigations link ancestral Menominee populations to intensive agricultural practices in the upper Great Lakes region, particularly during the Late Prehistoric period. At the Sixty Islands site along the Menominee River on the Michigan-Wisconsin border—recognized as part of the tribe's ancestral homeland known as Anaem Omot—LiDAR surveys and excavations have uncovered raised garden bed fields spanning approximately 330 acres (with only 40% surveyed), dating from around 1000 to 1600 CE.[16] [17] These represent the largest intact ancient Native American agricultural complex in the eastern United States, challenging prior assumptions of limited farming scale in northern latitudes near the viability limit for maize.[18] Farming techniques included constructing ridges 4 to 12 inches high from wetland soils, enriched with compost incorporating charcoal, ceramics, and household refuse, to cultivate maize alongside beans and squash.[16] [18] This method maximized productivity in a challenging climate, with fields rebuilt over centuries, integrating ceremonial and residential features into a complex anthropogenic landscape.[18] Similar raised bed systems appear on the modern Menominee Reservation in Wisconsin, where surveys of three ancestral sites reveal persistent vegetation differences—such as elevated species richness—attributable to over a millennium of maize agriculture, underscoring ecological legacies of these practices.[19] Subsistence evidence indicates a diversified economy emphasizing foraging, supplemented by horticulture, hunting, and fishing. Wild rice harvesting from lakes and rivers formed the cornerstone, with seasonal gathering of roots, berries, and other plants providing reliable staples in the forested environment.[5] Horticultural plots, though not dominant pre-contact, supported community needs through the crops identified in archaeological contexts.[5] Hunting focused on deer, small game, and trapping, while fishing targeted abundant species like sturgeon in regional waterways, ensuring nutritional resilience amid variable resources.[5] [20] This mixed strategy, evidenced by site distributions and oral traditions corroborated archaeologically, reflects adaptation to the aquatic and woodland ecosystems spanning Wisconsin and the Upper Peninsula.[16]Clan System and Social Organization

The traditional Menominee social structure was organized around a clan system comprising 34 clans grouped into five phratries, or divisions, each headed by a principal clan: Bear, Crane, Eagle, Moose, and Wolf.[21][22] These phratries functioned as extended kinship networks with specific societal roles, promoting balance and division of labor; for instance, the Wolf phratry specialized in hunting and gathering, while the Bear phratry held responsibilities for leadership and diplomacy. Clans were patrilineal, with descent and membership traced through the male line, such that children inherited their father's clan affiliation and associated rights, including access to resources and ceremonial duties.[5] Marriage rules enforced exogamy, prohibiting unions within the same clan to maintain alliances across phratries, which reinforced social cohesion and prevented inbreeding.[23] Each clan possessed totemic animals or symbols—such as the bear for the Bear phratry—that guided ethical conduct, subsistence practices, and spiritual reverence, with clans collectively ensuring sustainable resource management through assigned expertise.[24] Villages were semisedentary, comprising extended family clusters from multiple clans, led by hereditary chiefs typically from the Bear phratry, who mediated disputes and coordinated communal activities like maple sugaring or wild rice harvesting.[25] This phratral organization extended to governance, where consensus among clan leaders influenced decisions on warfare, trade, and migration, reflecting a decentralized yet interdependent system adapted to the Great Lakes region's ecology. Women held significant roles in domestic economy and clan continuity, managing horticulture and child-rearing, though formal authority rested with male elders.[5] The system's emphasis on reciprocity and ecological stewardship persisted into the contact era, informing responses to external pressures.Historical Interactions and Land Cessions

European Contact and Fur Trade Era

The first recorded European contact with the Menominee occurred in 1634, when French explorer Jean Nicolet arrived at Green Bay in their territory while seeking a passage to Asia.[3][5] Nicolet's expedition marked the initial interaction between the Menominee and Europeans, with the French dubbing them Folles Avoines ("wild oats") due to their reliance on wild rice.[5] French fur traders established relations with the Menominee shortly thereafter, initiating regular exchanges by 1667, where the tribe supplied beaver pelts and other furs in return for European goods such as metal tools, cloth, and firearms.[5] This trade prompted significant adaptations in Menominee society, including the dispersal of populations from large permanent villages to smaller, mobile bands that facilitated winter trapping expeditions, followed by seasonal returns for agriculture and fishing.[5] The credit system employed by traders often left Menominee hunters indebted, fostering economic dependence on sustained fur procurement. The Menominee allied closely with the French during conflicts, including the Fox Wars of the early 1700s, where they joined French forces and other tribes against the Meskwaki (Fox) to protect trade routes and territorial interests.[5] This partnership extended to the French and Indian War (1754–1763), after which France ceded control of the region to Britain under the Treaty of Paris.[5] Under British rule, the fur trade persisted through existing French-speaking traders, with Menominee continuing to supply furs amid ongoing intertribal dynamics and European commercial demands.[26]19th-Century Treaties and Territorial Reduction

The Menominee's territory at the onset of the 19th century spanned approximately 10 million acres across northeastern Wisconsin, the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, and adjacent areas.[27] A series of seven treaties with the United States from 1821 to 1854 systematically reduced this expanse through land cessions, primarily to accommodate white settlement, relocation of eastern tribes, and resource demands.[28] Early agreements included the 1821 treaty ceding a small tract along the Fox River to New York tribes such as the Oneida, Stockbridge-Munsee, and Brothertown, followed by the 1822 treaty transferring over 6.7 million acres to the same groups, though the latter was contested by the Menominee and Ho-Chunk for insufficient disclosure of terms.[2] The 1831 Treaty of Washington compelled cessions of about 500,000 acres west of the Fox River—bounded by Little Kakalin, Oconto Creek, and Green Bay—for New York Indians, plus 2.5 million acres southeast of Winnebago Lake encompassing areas to Milwaukee River and Lake Michigan directly to the United States, in exchange for $20,000 paid in installments.[29] Treaties in 1832 and 1836 further eroded holdings, with the latter Treaty of the Cedars involving sales in the Fox River valley; the 1831–1832 pacts alone yielded roughly 3.5 million acres to the U.S., some allocated to relocated tribes and the rest retained by the government.[2] Under pressure, the 1848 Treaty of Lake Poygan required cession of all remaining Wisconsin lands, granting in return at least 600,000 acres in Minnesota from prior Chippewa cessions, $350,000 apportioned for chiefs' settlements ($30,000), mixed-blood claims ($40,000), removal ($20,000), education and mills ($15,000), blacksmith services ($11,000 over 12 years), improvements ($5,000), and $200,000 in 10-year annuities starting 1857, plus interest from prior treaty funds.[30][2] Unsuitable Minnesota conditions prompted the 1854 treaty, exchanging that tract for a permanent reservation of about 250,000 acres along the Wolf River in Wisconsin, later diminished by 46,000 acres granted to the Stockbridge-Munsee in 1856.[2] By 1854, these instruments contracted Menominee territory from vast regional claims to the reservation's bounds, fundamentally altering their land base.[1]Reservation Formation in 1854

The Treaty of Wolf River, signed on May 12, 1854, at the Falls of Wolf River in present-day Wisconsin, established the permanent Menominee Indian Reservation.[31][2] The agreement involved Menominee leaders, including Principal Chief Oshkosh, and U.S. commissioners, who negotiated the retrocession of lands previously assigned to the tribe under the 1848 Treaty of Lake Poygan.[32][33] In exchange, the Menominee retained a defined territory comprising approximately 276,480 acres across 12 townships along the Wolf River, securing a stable homeland amid ongoing pressures from settler expansion and prior land cessions.[34] Key provisions of the treaty included the cession of all lands granted to the Menominee in 1848, located further west, while affirming exclusive rights to hunt and fish on the reserved lands "as long as the game lasts," reflecting the tribe's reliance on these resources for subsistence.[31][35] The U.S. government agreed to provide annuities, agricultural improvements, and support for schools and mills to aid the tribe's transition to reservation life, though implementation faced challenges due to limited federal oversight.[36] Ratified by the U.S. Senate on August 2, 1854, the treaty marked a pivotal reduction in Menominee territory from earlier expansive claims but provided a legally protected reserve amid the broader context of 19th-century removal policies.[33][8] This formation stabilized the Menominee's land base after decades of treaties that had diminished their holdings from millions of acres in the early 1800s to scattered assignments by the mid-19th century, enabling the tribe to focus on sustainable practices within the bounded area.[2][27] The reservation's establishment also preserved cultural continuity, as the selected Wolf River region offered abundant game and timber, aligning with tribal traditions of resource stewardship.[37] Subsequent adjustments, such as the 1856 cession of 46,000 acres in the southwest corner to the Stockbridge-Munsee community, further refined the boundaries but did not alter the core reservation defined in 1854.[2][36]