Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Boxing styles and technique

View on Wikipedia

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Throughout the history of gloved boxing styles, techniques and strategies have changed to varying degrees.[1] Ring conditions, promoter demands, teaching techniques, and the influence of successful boxers are some of the reasons styles and strategies have fluctuated.[2][3]

Boxing styles are primarily defined as a combination of a boxer's offensive strategy, guard or defensive system, stance and behavior in the ring.[4][5][6] Some boxers will change their style depending on who their opponent is, while others will use the same style regardless of their opponent.[3] For example, Floyd Mayweather Jr. is primarily known for his technical defense,[7] orthodox stance,[8] crab style,[9][10] out-fighting.[3] Yet at times he would switch his style, showboating in the ring,[7] fighting southpaw stance,[8] using a high guard,[11] and fighting on the inside.[3]

A boxer's style often aligns with their physical attributes.[3] For example, a boxer with a long reach is more likely to be an out-fighter that uses a long guard style compared to a fighter with a short reach.[3] A fighter that is naturally right handed is also more likely to fight from an orthodox stance compared to a left-handed boxer that is more likely to fight from a southpaw stance.[8] Though, physical attributes alone cannot predict a fighter's style as other factors such as gym culture and their trainer's philosophy also play a role.[2][3]

Boxing Styles

[edit]Every boxer uses one of the four offensive strategies or styles: Swarmer, Out-Boxer, Slugger and Boxer-Puncher.[4][12][13][1][14] While there are many different sub-categories for these styles, all boxers can be classified by one of the four main styles.

The Swarmer

[edit]The Swarmer (inside fighter, pressure fighter, crowder) fights very aggressively and in close-quarters.[4] This style involves bombarding the opponent with heavy attacks to prevent effective counters and wearing down the opponent's defenses by attrition. Notably, a swarmer is identified by their forward movement, prioritizing their positioning to throw numerous punches while crowding their opponent.[15] Boxers using this style consistently stay within or at the edge of the punching range of their opponent, forcing their opponent to engage 'on the back foot,' either retreating or attempting counter punches. This tends to require a large investment of energy (cardio) on the part of both fighters, meaning one goal of this style is to exhaust their opponent.[12] Swarmers typically also fight in crouches to heavily target body and to be able duck head shots more effectively.[14] In-fighters rely on large volumes of punches for offensive and defensive purposes against while in close range and in clinching by landing punches while offsetting some of the long range and counter shots from their opponents.[14]

Swarmer prioritize initiating engagements, usually by entering their opponent's punching range using a combination of footwork, feints and straight punches or uppercuts. Once inside of their opponent's range, their objective is to score (land punches), then quickly exit the engagement - ideally at the very edge of their opponent's punching range. A boxer may also exert pressure by initiating a clinch instead of exiting the engagement after punching while fighting in very close quarters.[14] Ideally, the swarmer will seek to leverage their weight over their opponent in the clinch, forcing their opponent to expend energy.

An effective swarmer normally possesses a good "chin",[4] as this style involves entering the punching range of their opponent before they can maneuver inside where they are more effective (one exception could be Floyd Patterson who was knocked down 20 times in 64 fights). [16] Swarmers are often shorter than other fighters with shorter reaches, as these fighters more frequently have to get inside of their opponent's punching range to land punches, though this is not always the rule.

Commonly known swarmers are:

- Henry Armstrong

- Carmen Basilio

- Bennie Briscoe

- Marcel Cerdan

- Julio Cesar Chavez

- Isaac Cruz

- Jack Dempsey

- Roberto Duran

- Alfonso Zamora

- Joe Frazier

- Gennady Golovkin

- Wilfredo Gomez

- Roman Gonzalez

- Harry Greb

- Ricky Hatton

- Naoya Inoue

- Jake LaMotta

- Marcos Maidana

- Rocky Marciano

- Julio Cesar Martínez

- Battling Nelson

- Bobo Olson

- Manny Pacquiao

- Floyd Patterson

- Aaron Pryor

- Donovan Ruddock

- Salvador Sanchez

- Leon Spinks

- Katie Taylor

- Mike Tyson

- Mickey Walker

- Micky Ward

- Winky Wright

- William Zepeda

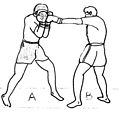

The Out-Boxer

[edit]The out-boxer (outside fighter, out-fighter, pure boxer) seeks to stay well outside of their opponent's punching range when disengaged and land long-range punches.[14][4][12] This style can be seen as an inverse of pressure fighting.[4][13] Out-boxers are known for quick movement and an emphasis on optimal positioning in the ring, known as 'ringcraft' or 'ring generalship.'[14] Since these fighters rely on punches from long range, the focus of these fighters tends to be obtaining a favorable position using footwork and feints then using the threat of these punches to draw counters from their opponent,[14][4][13] or else corral their opponents into unfavorable positions along the ropes or in the corner of the ring, thus making the opponent's movements much easier to anticipate. Using positioning outside of the opponent's range, a successful out-boxer will score using their jab and attempt to anticipate their opponent's response, applying an appropriate counter.[14][13]

Out-boxers rely on the defensive advantages given to them by staying outside of their opponents punching range.[14] Their opponent is forced to initiate engagements from this range,[13] and a successful out-boxer will attempt to reduce possible responses of their opponent using feints and footwork - in particular, achieving a favorable 'angle,' where the opponent is within the out-boxer's punching range while the out-boxer is outside of theirs.[14][4] An out-boxers style is often typified by speed and a focus on accurate punches over knockout blows.[16][14]

Out-boxers are generally taller fighters with long reach,[12] as these fighters tend to be more able to threaten punches from outside of their opponent's range.[12]

Commonly known out-boxers are:

- Laila Ali

- Muhammad Ali

- Dmitry Bivol

- Wilfred Benitez

- Ezzard Charles

- Billy Conn

- James J. Corbett

- Sunny Edwards

- Tyson Fury

- Naseem Hamed

- Devin Haney

- Thomas Hearns

- Larry Holmes

- Bakhodir Jalolov

- Jack Johnson

- Wladimir Klitschko

- Vitali Klitschko

- Benny Leonard

- Sugar Ray Leonard

- Nicolino Locche

- Vasiliy Lomachenko

- Tommy Loughran

- Leotis Martin

- Floyd Mayweather Jr.

- Willie Pep

- Caleb Plant

- Guillermo Rigondeaux

- Barney Ross

- Shakur Stevenson

- Gene Tunney

- Jersey Joe Walcott

- Andre Ward

- Pernell Whitaker

- Benjamin Whittaker

The Slugger

[edit]A slugger (brawler or puncher) is a boxing style that prioritizes raw power and knockout punches over technical finesse and strategy.[16][4][14] Their primary weapon is the ability to knock out an opponent with a single, powerful punch.[16][4][12][14] Offensively, sluggers possess the best balance and knockout capabilities due to their tendency to plant their feet on the ground while fighting.[14] They often have a thicker, stronger physique that allows them to generate and absorb heavy blows.[4][14] They favor slower, harder punches like hooks and uppercuts over fast combinations.[16][14] They tend to be slower, move less around the ring, and can have difficulty pursuing agile opponents.[16][4][12] Sluggers typically have strong chins and can take a lot of damage while waiting for an opening.[12][14] They apply constant pressure, close the distance, and aim to overwhelm their opponents with aggression.[14]

They are exciting to watch because their fights are unpredictable and often end in knockouts.[16][12] They are highly effective against "swarmers" who throw many punches but can be knocked out by one well-placed shot.[12][16] The style relies on brute strength and the philosophy that only one decisive blow is needed to win.[14] Their predictable punching patterns and slowness make them vulnerable to counterpunching from faster, more technical boxers.[16] They can tire quickly if they are unable to secure an early knockout.[14][16] Their lack of mobility and finesse can be exploited by agile opponents who use footwork and jabs.[14][16]

Commonly known sluggers are:

- Max Baer

- Iran Barkley

- David Benavidez

- Artur Beterbiev

- Oscar Bonavena

- Riddick Bowe

- Derek Chisora

- Bob Fitzsimmons

- Eric Esch

- Chris Eubank

- George Foreman

- Bob Foster

- Carl Froch

- Arturo Gatti

- Rocky Graziano

- Larry Holmes

- Julian Jackson

- James J. Jeffries

- Stanley Ketchel

- Vitali Klitschko

- Sergey Kovalev

- Carlos Zarate Serna

- Sonny Liston

- Luis Alberto Lopez

- Ron Lyle

- Subriel Matias

- Ricardo Mayorga

- Terry McGovern

- Ray Mercer

- Shane Mosley

- Donovan Ruddock

- Sandy Saddler

- John L. Sullivan

- Keith Thurman

- Kostya Tszyu

- Tim Tszyu

- Barbados Joe Walcott

- Deontay Wilder

- Harry Wills

- Zhilei Zhang

The Boxer-Puncher

[edit]The boxer-puncher possesses many of the qualities of the out-boxer: hand speed, often an outstanding jab combination, and/or counter-punching skills, better defense and accuracy than a slugger, while possessing brawler-type power. The boxer-puncher may also be more willing to fight in an aggressive swarmer-style than an out-boxer. In general, the boxer-puncher lacks the mobility and defensive expertise of the out-boxer (exceptions include Sugar Ray Robinson and Freddie Steele.) They are the most unpredictable among all 4 boxing styles. They don't fit in the rock-paper-scissors theory, so how the fight plays out between this style and other styles tends to be unpredictable. A boxer-puncher's ability to mix things up may prove to be a hindrance to any of the three other boxing styles, but at the same time their versatility means that they tend to be a master of none.

Commonly known boxer-punchers are:

- Janibek Alimkhanuly

- Canelo Álvarez

- Alexis Arguello

- Charley Burley

- Joe Calzaghe

- John Riel Casimero

- Miguel Cotto

- Terence Crawford

- Gervonta Davis

- Oscar De La Hoya

- Nonito Donaire

- Jaron Ennis

- Sebastian Fundora

- Joe Gans

- Tommy Gibbons

- Marvelous Marvin Hagler

- Thomas Hearns

- Evander Holyfield

- Bernard Hopkins

- Naoya Inoue

- Roy Jones Jr.

- Anthony Joshua

- Wladimir Klitschko

- Sam Langford

- Sugar Ray Leonard

- Lennox Lewis

- Vasyl Lomachenko

- Ricardo Lopez

- Teofimo Lopez

- Joe Louis

- Israil Madrimov

- Juan Manuel Marquez

- Floyd Mayweather Jr.

- Gerald McClellan

- Carlos Monzon

- Archie Moore

- Erik Morales

- Manny Pacquiao

- Sugar Ray Robinson

- Jesse Rodriguez

- Freddie Steele

- Felix Trinidad

- Oleksandr Usyk

- Andre Ward

- Jimmy Wilde

- Tony Zale

Other categories

[edit]Counterpuncher

[edit]A counterpuncher utilizes techniques that require the opposing boxer to make a mistake, and then capitalizing on that mistake. A skilled counterpuncher can utilize such techniques as winning rounds with the jab or psychological tactics to entice an opponent to fall into an aggressive style that will exhaust them and leave them open for counterpunches. Counterpunchers actively look for opportunities to bait an opponent into becoming too aggressive in order to capitalise on openings. Counterpunching can also be found in any of the four main boxing styles as it is not involved with range/distance but rather with the mentality of making an opponent miss and as a result making them pay. They are in the middle of offense and defence. As such, Muhammad Ali can be considered a counterpuncher even if he was an "outboxer", Tyson and Sugar Ray Robinson as well, despite the former being a "swarmer" and the latter a "boxerpuncher". For these reasons this form of boxing balances defense and offense but can lead to severe damage if the boxer who utilizes this technique has bad reflexes or is not quick enough.[17][5]

Commonly known counterpunchers are:

- Muhammad Ali

- Canelo Alvarez

- Charley Burley

- Terence Crawford

- Ezzard Charles

- Julio Cesar Chavez Sr.

- Roberto Duran

- Naseem Hamed

- Evander Holyfield

- Bernard Hopkins

- Naoya Inoue

- Roy Jones Jr.

- Sergio Martínez

- Juan Manuel Marquez

- Floyd Mayweather Jr.

- Archie Moore

- Willie Pep

- Jerry Quarry

- Salvador Sanchez

- Max Schmeling

- Errol Spence Jr.

- Shakur Stevenson

- James Toney

- Mike Tyson

- Jersey Joe Walcott

- Pernell Whitaker

Southpaw

[edit]A southpaw fights with a left-handed fighting stance as opposed to an orthodox fighter who fights right-handed. Orthodox fighters lead and jab from their left side, and southpaw fighters will jab and lead from their right side. Orthodox fighters hook more with their left and cross more with their right, and vice versa for southpaw fighters. Some naturally right-handed fighters (such as Marvin Hagler and Michael Moorer)[18][19] have converted to southpaw in the past to offset their opponents.

Commonly known southpaw fighters are:

- Janibek Alimkhanuly

- Joe Calzaghe

- Hector Camacho

- Terence Crawford (mainly fought Southpaw)

- Gervonta Davis

- Tiger Flowers

- Sebastian Fundora

- Marvelous Marvin Hagler (mainly fought Southpaw)

- Naseem Hamed

- Bakhodir Jalolov

- Zab Judah

- Erislandy Lara

- Vasiliy Lomachenko

- Frank Martin

- Sergio Martinez

- Manny Pacquiao

- Guillermo Rigondeaux

- Jesse Rodriguez

- Errol Spence Jr.

- Shakur Stevenson

- Josh Taylor

- Oleksandr Usyk

- Pernell Whitaker

- William Zepeda

Switch-hitter

[edit]A switch-hitter switches back and forth between a right-handed (orthodox) stance and a left-handed (southpaw) stance on purpose to confuse their opponents in a fight. Right-handed boxers would train in the left-handed (southpaw) stance, while southpaws would train in a right-handed (orthodox) stance, gaining the ability to switch back and forth after much training. A truly ambidextrous boxer can naturally fight in the switch-hitter style without as much training.

Commonly known switch-hitters are:

Equipment and safety

[edit]

Boxing techniques utilize very forceful strikes with the hand. There are many bones in the hand, and striking surfaces without proper technique can cause serious hand injuries. Today, most trainers do not allow boxers to train and spar without hand/wrist wraps and gloves. Handwraps are used to secure the bones in the hand, and the gloves are used to protect the hands from blunt injury, allowing boxers to throw punches with more force than if they did not utilize them.

Headgear protects against cuts, scrapes, and swelling, but does not protect very well against concussions. [citation needed] Headgear does not sufficiently protect the brain from the jarring that occurs when the head is struck with great force. [citation needed] Also, most boxers aim for the chin on opponents, and the chin is usually not padded. Thus, a powerpunch can do a lot of damage to a boxer, and even a jab that connects to the chin can cause damage, regardless of whether or not headgear is being utilized.

Stances

[edit]-

Upright stance

-

Semi-crouch

-

Full crouch

Upright stance – In a fully upright stance, the boxer stands with the legs shoulder-width apart and the rear foot a half-step in front of the lead man. Right-handed or orthodox boxers lead with the left foot and fist (for most penetration power). Both feet are parallel, and the right heel is off the ground. The lead (left) fist is held vertically about six inches in front of the face at eye level. The rear (right) fist is held beside the chin and the elbow tucked against the ribcage to protect the body. The chin is tucked into the chest to avoid punches to the jaw which commonly cause knock-outs and is often kept slightly off-center. Wrists are slightly bent to avoid damage when punching and the elbows are kept tucked in to protect the ribcage.

Crouching stance – Some boxers fight from a crouch, leaning forward and keeping their feet closer together. The stance described is considered the "textbook" stance and fighters are encouraged to change it around once it's been mastered as a base. Case in point, many fast fighters have their hands down and have almost exaggerated footwork, while brawlers or bully fighters tend to slowly stalk their opponents. In order to retain their stance boxers take 'the first step in any direction with the foot already leading in that direction.'[20]

Different stances allow for bodyweight to be differently positioned and emphasised; this may in turn alter how powerfully and explosively a type of punch can be delivered. For instance, a crouched stance allows for the bodyweight to be positioned further forward over the lead left leg. If a lead left hook is thrown from this position, it will produce a powerful springing action in the lead leg and produce a more explosive punch. This springing action could not be generated effectively, for this punch, if an upright stance was used or if the bodyweight was positioned predominantly over the back leg.[21] Mike Tyson was a keen practitioner of a crouched stance and this style of power punching. The preparatory positioning of the bodyweight over the bent lead leg is also known as an isometric preload.

Orthodox stance – refers to a stance where the left leg, and usually the left arm, is forward.

Southpaw stance – refers to a stance where the right leg, and usually the right arm, is forward.[22][23][24] Left-handed or southpaw fighters use a mirror image of the orthodox stance, which can create problems for orthodox fighters unaccustomed to receiving jabs, hooks, or crosses from the opposite side. The southpaw stance, conversely, is vulnerable to a straight right hand.

Switch hitting – refers to boxers who switch between an orthodox and southpaw stance.[25][6]

Open stance – refers to when one fighter is in an orthodox stance and the other is in a southpaw stance.[22][23][24]

Closed stance – refers to when both fighters are in orthodox stances or both fighters are in southpaw stances.[22][23][24]

Square stance – North American fighters tend to favor a more balanced stance, facing the opponent almost squarely.[26][27]

Bladed stance – many European fighters stand with their torso turned more to the side. The positioning of the hands may also vary, as some fighters prefer to have both hands raised in front of the face, risking exposure to body shots.[26][27]

Punching

[edit]

There are eight basic punches in boxing,[28] with six of them: the jab, cross, lead hook, rear hook, lead uppercut and rear uppercut, being the most used.[29][30][31][32][33] The lead overhand and rear overhand are the remaining basic punches.[28] Any punch other than a jab is considered a power punch. If a boxer is right-handed (orthodox), their left hand is the lead hand and his right hand is the rear hand.[29] For a left-handed boxer or southpaw, the hand positions are reversed.[29] When using these punches in combinations they are often referred to as numbers, with the jab being the number 1, cross being 2, lead hook 3, rear hook 4, lead uppercut 5 and rear uppercut 6.[29][30][31][32][28] For example, a jab and cross combination would be referred to as a 1-2 combination.[34][29]

- Jab — a quick, straight punch thrown with the lead hand from the guard position.[29] The jab extends from the side of the torso and typically does not pass in front of it. It is accompanied by a small, clockwise rotation of the torso and hips, while the fist rotates 90 degrees, becoming horizontal upon impact.[30][32] As the punch reaches full extension, the lead shoulder is brought up to guard the chin. The rear hand remains next to the face to guard the jaw. After making contact with the target, the lead hand is retracted quickly to resume a guard position in front of the face.[30][32] The jab is the most important punch in a boxer's arsenal because it provides a fair amount of its own cover and it leaves the least amount of space for a counter-punch from the opponent.[33] It has the longest reach of any punch and does not require commitment or large weight transfers. Due to its relatively weak power, the jab is often used as a tool to gauge distances, probe an opponent's defenses, and set up heavier, more powerful punches.[29][33] The power for the jab originates not from the arm, but from the legs.[30][32] The punch begins by pushing off the ball of the rear foot, transferring body weight forward into the strike.[30][32] A half-step may be added, moving the entire body into the punch, for additional power. Despite its lack of power, the jab is the most important punch in boxing, usable not only for attack but also defense,[31] as a good quick, stiff jab can interrupt a much more powerful punch, such as a hook or uppercut.

- Straight / Cross — a powerful straight punch thrown with the rear hand.[29] From the guard position, the rear hand is thrown from the chin, crossing the body and traveling towards the target in a straight line. The rear shoulder is thrust forward and finishes just touching the outside of the chin.[32] At the same time, the lead hand is retracted and tucked against the face to protect the inside of the chin. The power for the cross is generated from the ground up, originating from a strong push off the ball of the rear foot.[30][32] For additional power, the torso and hips are rotated counter-clockwise as the cross is thrown.[30][32] A measure of an ideally extended cross is that the shoulder of the striking arm, the knee of the front leg and the ball of the front foot are on the same vertical plane.[35] Weight is also transferred from the rear foot to the lead foot, resulting in the rear heel turning outwards as it acts as a fulcrum for the transfer of weight.[32] Like the jab, a half-step forward may be added. After the straight is thrown, the hand is retracted quickly and the guard position resumed.[30][32] The straight sets up the lead hook well. The Cross can also follow a jab, creating the classic "one-two combo."[29] When the same punch is used to counter a jab, aiming for the opponent's head it is called a "cross" or "cross-counter". A cross-counter is a counterpunch begun immediately after an opponent throws a jab, exploiting the opening in the opponent's position.

- Lead Hook — a semi-circular punch thrown with the lead hand or rear hand to the side of the opponent's head.[29] For a lead hook from the guard position in an orthodox stance, the elbow is drawn back with a horizontal fist (knuckles pointing forward) and the elbow bent. The rear hand is tucked firmly against the jaw to protect the chin. The torso and hips are rotated clockwise, propelling the fist through a tight, clockwise arc across the front of the body and connecting with the target. At the same time, the lead foot pivots clockwise, turning the lead heel outwards. Upon contact, the hook's circular path ends abruptly and the lead hand is pulled quickly back into the guard position. A lead hook may also target the lower body (the classic Mexican hook to the liver) and this technique is sometimes called the "rip" to distinguish it from the conventional hook to the head.

- Rear Hook — a close-range punch thrown with the rear hand. Power comes from a forceful counterclockwise rotation of the hips and torso, a counterclockwise pivot of the rear foot, and a weight transfer forward from the rear foot to the lead foot.[30][32] The elbow is bent at 90 degrees, and the fist travels in a tight, arcing motion to loop over an opponent's guard, making contact with the top two knuckles.[30][32] The hand can be positioned either palm-down (horizontal), or thumb-up (vertical).[30] The hand is immediately pulled back to the guard position after impact.[30][32]

- Lead Uppercut —a powerful, close-range vertical punch thrown with the lead hand, often targeting an opponent's chin or solar plexus.[28][29][31] Its upward trajectory makes it effective for breaking through an opponent's guard.[29] The punch begins by bending the knees and dropping into a three-quarter squat, shifting the majority of your weight onto the lead leg.[31] Power is explosively generated by driving upwards using the quadriceps of the lead leg.[30][32] From the guard, the lead hand drops about one foot to waistline height, forming a 90-degree angle at the elbow.[30][31][32] As the boxer explodes upwards, the punch travels in a vertical path, landing with the arm perpendicular to the floor and the palm facing yourself.[31][32] To maximize power, rotate the shoulder and torso as you drive the punch upward.[30][32] The punch should land square on the target at the midline of the opponent's body.[30][32] Immediately after impact, retract the hand back to the defensive guard position.[30][31][32]

- Rear Uppercut —a vertical, rising punch thrown with the rear hand.[29] For the rear uppercut by a boxer in an orthodox stance, from the guard position, the torso shifts slightly to the right, the rear hand drops below the level of the opponent's chest and the knees are bent slightly. From this position, the rear hand is thrust upwards in a rising arc towards the opponent's chin or torso. At the same time, the knees push upwards quickly and the torso and hips rotate counter-clockwise and the rear heel turns outward, mimicking the body movement of the cross. The strategic utility of the uppercut depends on its ability to "lift" the opponent's body, setting it off-balance for successive attacks.[36]

- Overhand — The overhand punch, also known as a drop or overcut, is a powerful, semi-circular strike thrown in a vertical, arcing motion designed to go over an opponent's guard or strike, like a jab, to hit their head.[28][37] Executed by driving off the back leg and dropping the body weight into the punch, its mechanics involve a coordinated step and weight transfer similar to throwing a baseball to generate significant power.[37] Depending on the fighter's stance, the footwork varies to either maintain a wide base for a quick retreat or to step in for more power and balance, though the punch often leaves the thrower exposed, requiring a defensive roll to avoid counters.[37]

Advanced punches

[edit]Advanced punches are usually only learned after boxers have mastered the basic punches. These punches are usually used less frequently and primarily by experienced boxers.

- Bolo punch — Occasionally seen in Olympic boxing, a bolo is an arm punch which owes its power to the shortening of a circular arc rather than to transference of body weight; it tends to have more of an effect due to the surprise of the odd angle it lands at rather than the actual power of the punch.[38][39]

- Check hook — A check hook is employed to prevent aggressive boxers from lunging in. There are two parts to the check hook. The first part consists of a regular hook. As the opponent lunges in, the boxer should throw the hook and pivot on his left foot and swing his right foot 180 degrees around. If executed correctly, the aggressive boxer will lunge in and sail harmlessly past his opponent like a bull missing a matador.

- Haymaker — A haymaker is a wide-angle punch similar to a hook, but instead of getting power from body rotation, it gets its power from its large loop. It is considered an unsophisticated punch, and leaves one open to a counter.[40][41]

- Shovel hook — a punch that combines elements of a traditional hook and an uppercut, often thrown at a 45-degree angle. It's designed to hit the opponent's body or chin, and the "shoveling" motion is meant to dig in, similar to using a shovel.[42]

- Gazelle punch — an advanced technique that involves a forward leap or jump during a punch, generating power and closing the distance quickly. It's a powerful, explosive move, often a left hook, used to catch opponents off guard. It's named for the way the boxer's legs propel them forward, mimicking a gazelle's leap.[43][39]

- Corkscrew Punch — involves a twisting motion of the arm upon impact, designed to increase power and defensive positioning. The core mechanic is not just a wrist turn, but a rotation of the entire arm (from the shoulder down) as the punch is thrown. The punch is thrown so that upon impact, the palm is facing downward. This rotation aligns the knuckles with the target for a cleaner, more powerful impact. The technique can be applied to various punches, though the specific motion differs slightly for each. The twisting motion automatically raises the shoulder to protect the chin from counter-punches.[44]

- Manila Ice — An advanced punching technique that involves a swift flowing right hook thrown by a southpaw over an orthodox opponent's jab, often as a counter. It usually targets the opponent's temple or jaw in-order to catch the opponent off guard and deal significant damage no one expected.[39]

Defense

[edit]Defense in boxing refers to actions taken by a boxer to avoid being hit, redirect an opponent's attack or reduce the impact of punches to vital areas such as the head. Defensive techniques generally fall into 4 categories of evading, blocking, covering and clinching.

Evading

[edit]Evading refers to actions a boxer takes to try to avoid strikes entirely by making their opponents miss.

-

Pulling away

-

Leaning back

- Slipping — involves moving the head slightly offline of an incoming punch, often by leaning and twisting the upper body.

- Bob-and-weave — bobbing moves the head laterally and beneath an incoming punch. As the opponent's punch arrives, the boxer bends the legs quickly and simultaneously shifts the body either slightly right or left. Once the punch has been evaded, the boxer "weaves" back to an upright position, emerging on either the outside or inside of the opponent's still-extended arm. To move outside the opponent's extended arm is called "bobbing to the outside". To move inside the opponent's extended arm is called "bobbing to the inside".

- Footwork — involves moving the feet to create angles, create distance, or get out of the way of punches, including linear and circular movements.

- Pulling — Moving the body backward to create distance and avoid punches.

- Leaning back — moving the upper body backward to evade punches, often combined with shifting weight onto the back leg.

- Sway / fade — To anticipate a punch and move the upper body or head back so that it misses or has its force appreciably lessened. Also called "rolling with the punch" or "riding the punch".

- Shoulder roll – To execute the shoulder roll a fighter rotates and ducks (to the right for orthodox fighters and to the left for southpaws) when their opponent's punch is coming towards them and then rotates back towards their opponent while their opponent is bringing their hand back.[45] The fighter will throw a punch with their back hand as they are rotating towards their undefended opponent.[45]

Blocking

[edit]Blocking refers to actions a boxer takes to absorb, redirect, intercept or slow the momentum of an opponents strikes preventing blows from impacting vital areas such as the head and midsection.

- Parry — parrying uses the boxer's hands as defensive tools to deflect incoming attacks.[46][47] As the opponent's punch arrives, the boxer delivers a sharp, lateral, open-handed blow to the opponent's wrist or forearm, redirecting the punch.[46][47] In a closed stance the boxer's lead hand parries the opponent's rear hand and the boxer's rear hand parries the opponent's lead hand.

- Low parry — is a defensive technique used to deflect punches aimed at the body, particularly low punches.[47] It involves moving the arm in a half-circle motion, typically starting from the outside and moving inwards, to clear the punch to the side.[47] This technique is effective because it avoids absorbing the impact from the punch directly, which can be more forceful and put you off balance, instead, it guides the punch away from the intended target.[47]

- Punch catch — is a defensive technique where a fighter uses their open palm to intercept an incoming punch, aiming to slow the momentum of the strike and stopping it from hitting its intended target.[46] Catching is often used for straight punches like the jab.[46]

- Uppercut catch — is a defensive technique where a fighter uses their open palm to intercept an incoming uppercut, aiming to slow the momentum of the strike and stopping it from hitting its intended target.[48] This is generally used against uppercuts to the head. In general when boxers are in a closed stance the boxer uses their rear hand to catch a lead uppercut and their lead hand to catch a rear uppercut. In an open stance the boxer generally uses their lead hand to catch a lead uppercut and their rear hand to catch a rear uppercut.

- Cross block — is often done with the rear arm (right for an orthodox fighter and left for a southpaw) but can also be done with the lead arm (left for an orthodox fighter and right for a southpaw).[49][50] In a cross block position with the rear hand, the glove is over the lead shoulder with the palm facing towards the opponent.[50] Using the lead hand the glove is over the rear shoulder with the palm facing towards the opponent.[49][50] With the cross block the glove is usually used to block straight punches, but the forearm can also be used.[49][50] The forearm and elbow can be used to block uppercuts, and the glove and elbow can also be used to block hooks.[49][50]

- Wedge block — also known as the horizontal forearm block or leverage block. This block is used primarily with the lead arm to defend against straight punches by moving the arm upwards towards the incoming punch.[51][52][53] It can be used against hooks by moving the arm up and outwards towards the incoming hook, or outwards to jam uppercuts in boxing.[54]

- Forearm body blocks — Boxers, especially classic guard fighters, will often turn their body towards straight strikes and uppercuts to the midsection using their vertical forearms to block.

- Elbow body blocks — Boxers often use their elbows to block hooks to the liver and kidneys by moving their elbows or leaning their bodies so the elbow connects with their opponent's fists.[55]

- Reverse elbow block — Crab Style fighters are unique as the low lead allows them to use the reverse elbows to block their heads.[56][57] The reverse elbow block can be used from a shoulder roll position.[58] The reverse elbow block also functions as an intermediating position between a wedge block and a shoulder roll, allowing a boxer to move from a reverse elbow block to a wedge block or shoulder roll.

- Shoulder block — a defensive technique where a fighter uses their shoulder to deflect or block punches, particularly the opponent's lead hand punch like a right cross or a southpaw jab.[45] The fighter positions their lead shoulder high, tucking their chin behind it.[45] The shoulder is rolled forward to meet the incoming punch, deflecting it away from the head and body.[45]

"If, however, his right lead is thrown at you when you are out of normal position-when, for example, you have permitted your left hand to drop down in an overzealous feint to the body-you must block with your left shoulder. You give your left shoulder a frantic, whirling hunch to protect your already snuggled chin. Thus, the blow thuds into your shoulder instead of into your face (Figure 53). You'll be tempted to use your right hand to help your left shoulder in that block. You'll be tempted to make a "shell defense" with shoulder and hand. But don't do it. You've got to keep that right hand in its normal position, ready to (1) guard against the possibility of a following left hook, and (2) smash a straight right counter to your opponent's solar plexus or chin." - Jack Dempsey's Championship Boxing Explosive Punching and Aggressive Defense.[59]

Covering

[edit]Covering refers to action a boxer takes to reduce the impact of strikes to vital areas such as the head and midsection. Unlike blocking, covering puts the gloves on the boxer's head or body directly. Some damage is still done to the boxer while covering, but the goal is to reduce the damage by using the gloves or arms as shock absorbers lessening the severity of blows.

-

Covering (with the gloves)

- Covering – covering up is the last opportunity to avoid an incoming strike to an unprotected face or body. Generally speaking, the hands are held high to protect the head and chin and the forearms are tucked against the torso to impede body shots. When protecting the body, the boxer rotates the hips and lets incoming punches "roll" off the guard. To protect the head, the boxer presses both fists against the front of the face with the forearms parallel and facing outwards. This type of guard is weak against attacks from below.

- Hook cover – a hook cover is a defense against a hook where a boxer raises their hand up, bending the elbow as if answering a phone creating a position where the glove covers the head against the hook.[60] The chin is also tucked while covering.[60] The boxer may also slightly lean the upper body away from the incoming hook, coordinating this lean with a small step or shift in their weight to maintain balance and create space for a counter.[60]

- Helmet cover – also known as a Hammer cover, is a variation of the Hook cover. It is a defensive technique where a fighter raises their forearm and hand to protect their head, it resembles a person using a hammer.[61] This technique is often used when facing opponents who throw high-impact punches to defend against hooks and overhands.[61]

Clinching

[edit]Clinching refers to grappling techniques a boxer uses to tie up an opponent's arms to prevent them from striking, or lessen the impact of strikes. Clinching techniques can also be used to move an opponent to a position where they are unable to effectively strike from. Clinching also includes framing, pinning, posting and trapping an opponent's hand or arm to prevent them from punching.[62][63][64]

- Clinch – clinching is a rough form of grappling and occurs when the distance between both fighters has closed and straight punches cannot be employed. In this situation, the boxer attempts to hold or "tie up" the opponent's hands so he is unable to throw hooks or uppercuts. To perform a clinch, the boxer loops both hands around the outside of the opponent's shoulders, scooping back under the forearms to grasp the opponent's arms tightly against his own body. In this position, the opponent's arms are pinned and cannot be used to attack. Clinching is a temporary match state and is quickly dissipated by the referee.

- Arm-in hug usually occurs when the opponent is in a high guard while changing levels to enter the clinch. The arms are wrapped around the opponent, covering the whole body. This action traps their arms on the inside, preventing them from punching. The arm-in hug is a rather weak position that should not be relied on too much as an opponent can easily break out of it by pushing, or putting a frame with the forearm or elbow.[64]

- Underhook is a position that a boxer may use in a clinch. The boxer's arm is placed under their opponent's arm or armpit. Their hand can be placed on their upper arm, shoulder or back. It is often used in combination with other arm positions such as an overhook which is called an over-under position. When a boxer secures one underhook it is called a single underhook and when using both underhooks it is called double underhooks. An underhook can be used to push the opponent's arm down or lift the opponent up and destabilize them, breaking their balance and getting them off their base.[64]

- Collar tie also known as the head pull, is a clinch technique.[65] From a closed stance the boxer uses the lead hand to grab the opponent's rear side collar or the back of their neck and their forearm presses against the opponent's collarbone or the back of their neck to control their posture and head movement.[65][66] If the boxer uses their rear hand in a closed stance they would grab their opponents lead side. The goal is to control the opponent's head by bending it down.[65][66] This allows the boxer to set up attacks like uppercuts and hooks, or to create angles.[65] A properly executed collar tie involves pressing the elbow to the chest and using the forearm to create a strong frame, preventing the opponent from escaping or generating power for their own attacks.[65] When one collar tie is used it is called a single collar tie and when two collar ties are used it is called a double collar tie.

- Cross collar tie also known as a forearm smash, is a clinch technique.[65] From a closed stance the boxer uses the lead hand to go across their body to grab the opponent's lead side collar, or the back of their neck and their forearm presses against the opponent's collarbone or the back of their neck to control their posture and head movement.[65] If the boxer uses their rear hand in a closed stance they would cross their body and grab their opponents rear side. The goal is to control the opponent's head by bending it down and to the side. This allows the boxer to set up attacks like uppercuts and hooks, or to create angles. A properly executed cross collar tie involves using the forearm to create a strong frame, preventing the opponent from escaping or generating power for their own attacks.[65] The boxer can also grab the opponent's shoulder and pull it down and to the side in the same way as they would against their opponent's head.[67] The cross collar tie is often used with an elbow tie on the same side to keep an opponent from punching and allowing the boxer to circle outside of their opponent.[67]

- Front headlock or chancery, is when a fighter secures a clinch, then uses their shoulder and arm to lock the opponent's head under their armpit. An opponent will often go for a headlock to get out of a defensive body lock that has been applied. To defend against this headlock, one should walk their hips under for a straighter posture and use their legs to lift up. This action will either force the opponent to release the grip or lift them off their feet.[64]

- Framing is a defensive technique where a boxer uses their hand, forearm, or body to control an opponent's position, create distance, or disrupt their balance. By establishing a physical barrier, framing can prevent punches, set up counters, manipulate an opponent's guard, or create openings for a boxer's own attacks. Boxing utilizes different frames, including entrance frames for closing distance and exit frames for creating space after an attack.[62][63]

Guards

[edit]There are 4 main defensive positions (guards or styles) used in boxing:

All fighters have their own variations to these styles. Some fighters may have their guard higher for more head protection while others have their guard lower to provide better protection against body punches. Many fighters don't strictly use a single position, but rather adapt to the situation when choosing a certain position to protect them.[16]

Classic Guards or Basic Guards: The modern Classic Guards are often the first Guards taught to boxers as the initial guard position is easy to learn,[68][69] and they are effective against haymakers,[70] which is the type of punch many untrained fighters and beginners use often.[40][41] Guards fitting into this category include:

- Traditional Guard - This guard involves bending both arms at 90 degrees or less, with the lead arm extended slightly away from the head and the rear fist held near the chin or jaw.[71] This guard offers passive defense[72] against hooks by using the gloves, forearms, and elbows to block,[73][74] while the bent-arm position allows for powerful punches and better visibility than other classic guards.[75] However, it leaves the centerline exposed, requiring quick reflexes and active defense, like parries, against straight punches and uppercuts, which can be difficult to master due to the need for specific blocking.[75][71][47][74] The guard also limits close-range effectiveness and lateral movement, as the high hand position makes punches more predictable, and reliance on blocking with the hands can delay counterpunching opportunities.[75]

- Conventional Guard - This guard involves holding both arms bent at 90 degrees or less, with the lead arm guarding the side of the head and the rear fist near the face or chin, offering passive defense against hooks by using gloves and elbows while enabling powerful punches due to the bent-arm position.[74] It benefits fighters with slower reflexes by keeping hands closer for quicker blocks and parries but limits visibility and leaves the centerline exposed, requiring active defense against straight punches and uppercuts.[75][47][74] It lacks redundant defense lines, relying heavily on hand blocks, which can delay counterpunches and make fighters vulnerable to hand traps, framing, and predictable punches.[62] Mastering this guard demands high defensive specificity despite its initial ease of learning.[63][75]

- High Guard - This guard involves bending both arms at 90 degrees or less, positioning the gloves in front of the face at eyebrow level, with hands resembling holding binoculars or making a heart shape,[71] with raised shoulders to protect the jaw and elbows pressed together to block uppercuts.[76] Its advantages include ease of learning, passive defense against straight punches, uppercuts, partial defense against hooks, and better power generation due to bent arms, while also protecting the centerline.[74][75] However, it limits visibility, allows opponents to close distance more easily, leaves ears and jaw exposed to hooks,[77] and exposes the lower body to attacks, relying heavily on forearm blocking, which can cause cumulative damage.[78][79] Additionally, it offers only one line of defense, makes counterpunching slower,[63][80] and leaves fighters vulnerable to hand traps,[62] framing, and split guards, though skilled boxers can bait opponents into counterattacks.[11][81]

Peek-a-Boo — a counter-offense style often used by a fighter where the hands are placed in front of the boxer's face,[82] like in the babies' game of the same name. It offers extra protection to the face and makes it easier to jab the opponent's face. Peek-a-Boo boxing was developed by legendary trainer Cus D'Amato. Peek-a-Boo boxing utilizes relaxed hands with the forearms in front of the face and the fist at nose-eye level. Other unique features includes side to side head movements, bobbing, weaving and blind siding your opponent. The number system e.g. 3-2-3-Body-head-body or 3-3-2 Body-Body-head is drilled with the stationary dummy and on the bag until the fighter is able to punch by rapid combinations with what D'Amato called "bad intentions." The theory behind the style is that when combined with effective bobbing and weaving head movement, the fighter has a very strong offense, defense and becomes more elusive, able to throw hooks and uppercuts with great effectiveness. Also it allows swift neck movements as well as quick ducking and strong returning damage, usually by rising uppercuts or even rising hooks.[16] Since it is a defense designed for close range fighting, it is mainly used by in-fighters. Bobo Olson was the first known champion to use this as a defense. In relation to the physical requirements of this style, a fighter is advised to have very strong and explosive legs. This is because of the sheer amount of bobbing and weaving. Since a fighter closes the gap with an opponent, they must be constantly moving in order to be able to find counters. If they stagnate, they are left in a very vulnerable position, able to be "outboxed" by long range fighters.

Commonly known Peek-A-Boo fighters include:

Crab Style Guards: Work at all ranges, allowing fighters to defend while countering—such as using a lead arm to block jabs while keeping the rear hand free to punch. The style adapts to different boxing approaches: infighters use it to advance safely, out-boxers rely on one-handed defense to strike while evading, and sluggers use it to cover up after missed power shots. Its flexibility makes it effective for both offense and defense. The many variations of this defense include:

- Cross-armed guard (sometimes known as the armadillo) - the forearms are placed on top of each other horizontally in front of the face with the glove of one arm being on the top of the elbow of the other arm.[56] This style is greatly varied when the back hand (right for an orthodox fighter and left for a southpaw) rises vertically. In some cases, one hand is across the face with the forearm horizontal or diagonal. While the other lies low, protecting the body.[83] This style is used for reducing head damage at close range, but can be used to defend the body as well.[83] The only head punch that a fighter is susceptible to is a punch to the top of the head.[83] The body is open if the guard is kept high, but most fighters who use this style bend and lean to protect the body, but while upright and unaltered the body is there to be hit. This position can be difficult to counterpunch from for beginners, but can be highly effective for counterpunching by more experienced fighters.[84] It also virtually eliminates all head damage. In close range a slightly crouched posture can be used and usually a front foot heavy squared stance.[85] Meaning that the now protected head of the boxer, is a closer target than the body. However, this guard is also effective in a bladed stance and while moving or leaning backwards to block an opponent's counterpunches after a missed punch.[86][85]

- Reverse cross-armed guard - The forearms can be placed on top of each other horizontally or diagonally in front of the face with the lead arm (left for an orthodox fighter and right for a southpaw) being on the top of the rear arm with lead glove over the rear shoulder.[56] The position of the lead arm (left for an orthodox fighter and right for a southpaw) is greatly varied when it rises vertically.[87]

Commonly known Cross-Armed fighters include:

- Max Baer

- Dereck Chisora (in the fight with Joyce)

- Juan Francisco Estrada

- George Foreman (in his comeback)

- Gene Fullmer

- Joe Frazier

- Evander Holyfield

- Gunner Moir

- Archie Moore

- Ken Norton

- Gus Ruhlin

- David Tua (occasionally)

- Paolino Uzcudun

- Tim Witherspoon

- Ad Wolgast

Philly Shell or Michigan Defense — This is a variation of the cross-armed guard.[56] The lead arm (left for an orthodox fighter and right for a southpaw) is placed across the abdomen, below the rear arm, to protect the body.[56] The head is titled towards the rear shoulder to keep the head off of center-line, and to make space to use the shoulder to block.[56] The lead shoulder is brought in tight against the side of the face.[56] The rear hand can be placed next to the chin close to the rear shoulder (right side for orthodox fighters and left side for southpaws) to defend against hook punches, placed in a cross block position, with the rear hand over the lead shoulder to protect against straight punches, or on the centerline to be able to rotate between a hook cover and a cross block or punch catch position.[56] This style is used by fighters who like to counterpunch. To execute this guard a fighter must be very athletic and experienced. This style is so effective for counterpunching because it allows fighters to slip punches by rotating and dipping their upper body and causing blows to glance off the fighter. After the punch glances off, the fighter's back hand is in perfect position to hit their out-of-position opponent.[45] The weakness to this style is that when a fighter is stationary and not rotating they are open to be hit so a fighter must be athletic and well conditioned to effectively execute this style. To beat this style, fighters like to jab their opponents shoulder causing the shoulder and arm to be in pain and to demobilize that arm. But if mastered and perfected it can be an effective way to play defense in the sport of boxing.

Commonly known philly shell fighters include:

- George Benton

- Charley Burley

- Terence Crawford

- Jaron Ennis

- Devin Haney

- Naoya Inoue

- Floyd Mayweather Jr.

- Caleb Plant

- Dmitry Pirog

- Dwight Muhammad Qawi

- Sugar Ray Robinson

- Shakur Stevenson

- James Toney

- Pernell Whitaker

Long guards also knows as Extended Guard: In boxing these guards are often used by taller fighters or fighters with longer reach to keep opponents out of punching range, but shorter fighters or fighters with shorter reach often use them intermittently.[88][89][90] Variations include:

- Classic Long Guard - The is a hybrid guard that combines the extended lead arm of the mummy guard with the rear hand in a classic guard, typically positioned at a 90-degree angle near the face.[89][90] Advantages include the lead hand controls distance, blocks vision, parries, traps hands, and frames.[89] The rear hand remains ready for power punches and defends against hooks.[91][92] Disadvantages include a weak passive defense against uppercuts and straights that bypass the lead arm.[93] Powerful lead hooks and uppercuts are harder to throw since the arm must retract first, telegraphing the punch. It exposes the lead side of the body and allows opponents to gauge reach and distance easily.

- Mummy Guard is a boxing stance where both arms are extended with slightly bent elbows and palms facing the opponent, while the chin is tucked and shoulders are raised for protection.[88] This guard allows fighters to block their opponent's vision and smother jabs, particularly against Classic or Peek-a-boo guards, though it is less effective against low-hand styles like the Crab Guards.[88] Taller fighters benefit from this stance as it discourages hooks and uppercuts, while shorter fighters can adjust by raising their shoulders and tucking elbows.[88] However, the Mummy Guard limits power punches since strikes require retracting the arms first, telegraphing movements and leaving the lead side vulnerable. Additionally, opponents can exploit lateral movement to close the distance and land punches before the extended arms can react.[94]

- Dracula Guard - A hybrid boxing guard that combines elements of the extended lead arm of the Mummy guard and the rear hand in a Cross Guard positioned for defense.[93][89] Named for its resemblance to Dracula hiding behind a cape, it uses the lead arm to block vision, control distance, parry, and trap hands, while the rear hand remains ready for power punches and defense.[93] Advantages include that it is good for obscuring vision and setting up traps. Allows quick jabs and rear hand power punches. Protects against straight punches, hooks, and uppercuts. Disadvantages include it limits powerful lead hooks and uppercuts as it requires pulling the arm back first, telegraphing the strike. Exposes the lead side of the body and makes reach more predictable.[94]

Theories

[edit]Centerline Theory - a theory that is a fundamental concept in boxing, referring to an imaginary vertical line running down the middle of a fighter's body, crucial for both offense and defense.[95] In boxing, staying on the centerline makes a fighter vulnerable to straight punches like jabs and crosses, so skilled boxers shift off it to evade attacks using techniques like slipping, shoulder rolls, and lateral movement.[96] Offensively, targeting an opponent's centerline allows for efficient strikes such as straight punches, hooks, and uppercuts, while defensive strategies like the Philly Shell and Peekaboo styles emphasize protecting the centerline by angling the body, slipping, using shoulder deflection, and the importance of manipulating angles to exploit the centerline while minimizing exposure to counterattacks.

Triangle Theory - a theory in boxing that uses equilateral triangles to create advantageous angles for striking while minimizing an opponent's ability to counter. It positions the opponent at the triangle's center and maneuvers along its edges to attack from 45-degree angles, disrupting their defense and enabling effective counters. While highly effective in boxing due to its restricted rules (e.g., no spinning strikes), the theory is less applicable in other martial arts, where techniques like kicks, backfists, and stance-switching allows fighters to counter angular movements more easily, making the strategy riskier outside of boxing.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "Boxing Styles". Retrieved 2025-08-12.

- ^ a b "How to Choose Your Fighting Style". Retrieved September 1, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g "How to Choose Your Boxing Style". Retrieved September 1, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "The 4 Different Boxing Styles | FightCamp". blog.joinfightcamp.com. Retrieved 2023-03-21.

- ^ a b "5 Different Fighting Styles in Boxing". Retrieved 1 September 2025.

- ^ a b "Boxing Styles". Retrieved September 1, 2025.

- ^ a b "10 of the Flashiest Boxers in History". Retrieved 25 April 2025.

- ^ a b c "Orthodox vs. Southpaw". Retrieved September 1, 2025.

- ^ "Boxing:Floyd Mayweather Jr. and Contemporary Science". Retrieved 25 April 2025.

- ^ "Breaking Down the Mayweather Style of Boxing". Retrieved 25 April 2025.

- ^ a b "High Guard Bait and Pull Counter". Retrieved 25 June 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "4 Styles Of Boxing". www.legendsboxing.com. Retrieved 2024-06-25.

- ^ a b c d e "Discover Your Boxing Style". Retrieved 2025-08-12.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u "Boxing Styles". Retrieved 2025-08-12.

- ^ "The Swarmer: Focusing on Fighting Styles - Part 1". boxingroyale.com. Retrieved 2023-03-21.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Boxing Styles". argosummitboxing.com. Archived from the original on 2013-07-05.

- ^ "The Counter Puncher Style in Boxing". 5 January 2024.

- ^ "Marvin Hagler – The Marvelous One!". 10 October 2010.

- ^ "Michael Moorer". boxrec.com. Retrieved May 13, 2023.

- ^ Dempsey, Jack, 'Footwork' in Championship Fighting Explosive Punching and Aggressive Defense, 1950

- ^ Dempsey, Jack, 'Stance' in Championship Fighting Explosive Punching and Aggressive Defense, 1950

- ^ a b c "Establishing an Inside Foot Positionin the Open Stance".

- ^ a b c "Southpaw Boxing Stance".

- ^ a b c "Orthodox vs. Southpaw".

- ^ "Best Style of Boxing".

- ^ a b "The Pros and Cons of Stances".

- ^ a b "Boxing Stances".

- ^ a b c d e "Basic Boxing Punches 1-8". Retrieved August 21, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Boxing Combos". Retrieved August 11, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r "Ultimate Guide to Punch Number System". Retrieved August 11, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "6 Punches". Retrieved August 11, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t "The Punch Number System 1-6". Retrieved August 11, 2025.

- ^ a b c "Boxing Fundamentals Understanding the Boxing Punch Number System". Retrieved August 11, 2025.

- ^ "Johnny's Punching Combinations List". Retrieved August 11, 2025.

- ^ Patterson, Jeff. "Boxing for Fitness: Straight Right". nwfighting.com. Northwest Fighting Arts. Retrieved 12 March 2014.

- ^ "Different Types of Punches in Boxing 2022 | Kickboxing | MMA". myboxingheadgear.com. Jul 13, 2020. Retrieved May 14, 2023.

- ^ a b c "How to Set up and Land an Overhand Right in Boxing". Retrieved 21 August 2025.

- ^ "The Bolo Punch". Retrieved 2025-08-12.

- ^ a b c "5 Signature Punches In Boxing". Retrieved 2025-10-12.

- ^ a b "The Ultimate Guide to Haymaker Punch". Retrieved 25 June 2025.

- ^ a b "What is a Haymaker Punch". Retrieved 25 June 2025.

- ^ "How to Throw a Shovel Hook in Boxing". Retrieved 2025-08-12.

- ^ "How to Perfect the Gazelle Punch Technique in Boxing". Retrieved 2025-08-12.

- ^ "What is the Corkscrew Punch in Boxing". Retrieved 2025-08-12.

- ^ a b c d e f "Aggressive Defense Paperback Pages 53-55". Retrieved 25 April 2025.

- ^ a b c d "Block, Catch, Parry". Retrieved 25 April 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g "How to Parry Punches". Retrieved 25 June 2025.

- ^ "Aggressive Defense Paperback Page 26". Retrieved 25 April 2025.

- ^ a b c d "Gene Fullmer Reverse Cross Guard Defense". YouTube. Retrieved 20 July 2025.

- ^ a b c d e "How to Cross Block and Roll With Punches". YouTube. Retrieved 20 July 2025.

- ^ "Using the Wedge Block". Retrieved 25 April 2025.

- ^ "How to Improve Your Lead Hand for Boxing". Retrieved 25 April 2025.

- ^ "12 Boxing Techniques & Combinations From The Philly Shell". Retrieved 25 April 2025.

- ^ "George Benton Deflects Uppercut". YouTube. Retrieved 20 July 2025.

- ^ "Boxing 101 Catching and Blocking". Retrieved 25 April 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Aggressive Defense Paperback Pages 120-162". Retrieved 25 April 2025.

- ^ "Philly Shell Defense Explained". Retrieved 25 April 2025.

- ^ "How Floyd MAYWEATHER uses his ELBOW for Philly Shell DEFENSE". YouTube. Retrieved 25 July 2025.

- ^ Dempsey, Jack (1950). Championship Fighting Explosive Punching and Aggressive Defense (PDF) (first ed.). Self published. p. 104.

- ^ a b c "Aggressive Defense Paperback Pages 56-60". Retrieved 25 April 2025.

- ^ a b "What is Hammer Block in MMA". Retrieved 25 April 2025.

- ^ a b c d "Boxers Guide to Inside Fighting". Retrieved 25 June 2025.

- ^ a b c d "Apollos Boxing Tips". Retrieved 25 June 2025.

- ^ a b c d "Learn How to Clinch in Boxing". YouTube. Retrieved 25 September 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "10 Floyd Mayweather Boxing Tricks". Retrieved September 1, 2025.

- ^ a b "Roger Mayweather Mitt Work". YouTube. Retrieved 25 September 2025.

- ^ a b "Floyd Mayweather Padwork". YouTube. Retrieved 25 September 2025.

- ^ "Top 5 Boxing Guards You Should Know". Retrieved 25 June 2025.

- ^ "Essential Boxing Guards". Retrieved 25 June 2025.

- ^ "Slugger Boxing Style". Retrieved 25 June 2025.

- ^ a b c "Complete Boxing Beginners Guide". Retrieved 25 June 2025.

- ^ "Active and Passive Defense". Retrieved 25 June 2025.

- ^ "5 Boxing Guards to Study". Retrieved 25 June 2025.

- ^ a b c d e "Catching and Blocking". Retrieved 25 June 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f "Boxing MMA Guard". Retrieved 25 June 2025.

- ^ "Boxing Guards". Retrieved 25 June 2025.

- ^ "How Mayweather Broke the High Guard". YouTube. Retrieved 25 August 2025.

- ^ "Types of Guards". Retrieved 25 June 2025.

- ^ "Crucial Defensive Techniques". Retrieved 25 June 2025.

- ^ "Boxing High Guard". Retrieved 25 June 2025.

- ^ "Boxing Dictionary". Retrieved 25 June 2025.

- ^ "The Science of Mike Tyson and Elements of Peek-A-Boo: part II". SugarBoxing. 2014-02-01. Archived from the original on 2015-09-25. Retrieved 2014-09-18.

- ^ a b c "Solving Styles: Reverse Engineering Archie Moore and the Lock Part 1". Retrieved 3 August 2025.

- ^ "The Cross Arm Guard in Boxing". Retrieved 25 April 2025.

- ^ a b "Genius of the Cross Guard". YouTube. Retrieved 20 July 2025.

- ^ "How to Use the Cross Guard". YouTube. Retrieved 20 July 2025.

- ^ "Gene Fullmer Reverse Cross Guard Defense". Retrieved 25 April 2025.

- ^ a b c d "George Foreman Student of the Greats".

- ^ a b c d "How to Use the Long Guard in Boxing".

- ^ a b "Types of Boxing Guard".

- ^ "Long Guard Boxing".

- ^ "Start Using the Long Guard Effectively".

- ^ a b c "What is the Muay Thai Dracula Guard".

- ^ a b "Getting Past the Post".

- ^ "Breaking Down the Mayweather Style of Boxing". Retrieved 20 July 2025.

- ^ "The Shell Game". Retrieved 20 July 2025.

External links

[edit]Boxing styles and technique

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Stances

In boxing, the stance forms the foundational body position that ensures balance, mobility, and optimal reach for both offensive and defensive actions. It involves precise alignment of the feet, knees, and upper body to distribute weight effectively while minimizing exposure to strikes. Proper stance setup allows boxers to pivot, advance, or retreat fluidly, integrating seamlessly with hand guards for comprehensive protection.[1][2] The orthodox stance, used primarily by right-handed boxers, positions the left foot forward and the right foot slightly behind, with feet approximately shoulder-width apart or slightly wider. The front foot points forward at a 30-45 degree angle, while the back foot angles at 45-60 degrees, aligning the heels in a toe-to-heel line for stability. Weight is distributed evenly at 50/50 between both legs, or slightly favoring the rear (55/45), with knees bent to maintain a low center of gravity and enable explosive movement; the upper body remains slightly turned (bladed) to protect the torso, shoulders relaxed, elbows tucked in, hands held high near cheek level, and chin tucked down toward the chest to shield the jaw from impacts. This alignment reduces vulnerabilities such as overexposure of the jaw or midsection by keeping the body compact and ready for pivots.[1][2][3] The southpaw stance mirrors the orthodox for left-handed boxers, placing the right foot forward and left foot back, with similar shoulder-width spacing and angular foot positioning. Weight distribution and knee bend follow the same principles, but the reversed setup creates advantageous angles against orthodox opponents, as the lead right hand can target the rival's open side while the powerful left rear hand gains extended reach for crosses. This configuration enhances unpredictability in footwork and punch trajectories, though it demands familiarity to avoid crossing lines during exchanges.[4][5] Neutral and bladed stances represent variations in body orientation and width for adaptability. A neutral stance adopts a more squared posture with feet shoulder-width apart and the body facing the opponent more directly, promoting balanced weight distribution and 360-degree mobility but increasing torso exposure; knees remain slightly bent, upper body upright with hands up and chin tucked. In contrast, the bladed stance turns the body sideways to present a narrower profile, with feet aligned as in orthodox/southpaw but emphasizing shoulder roll and elbow positioning to cover the ribs—ideal for evasion, though it may limit forward power if overly extreme. Both prioritize knee flexion for spring-like responsiveness and upper body alignment to avoid jaw overextension.[1][3] Historically, boxing stances evolved from the bare-knuckle era's upright, extended-arm positions focused on endurance and grappling under unregulated rules, to the gloved modern form introduced by the Marquess of Queensberry Rules in 1867, which emphasized padded protection, timed rounds, and technical precision. This shift favored bent-knee, balanced setups for agility over raw standing power, enabling sophisticated footwork. Rocky Marciano's narrow, flat-footed stance with a pronounced crouch and waist-bend—precursors to the formalized peek-a-boo style—influenced later defensive alignments by demonstrating how low, off-center positioning could deflect blows while facilitating aggressive advances, inspiring adaptations in 20th-century heavyweights for enhanced vulnerability reduction.[6][7]Guards

In boxing, guards refer to the strategic positioning of the hands, arms, and shoulders to shield the head and torso from incoming strikes while maintaining readiness for offensive actions. These positions form the foundation of a boxer's defensive framework, integrating with the overall stance to optimize balance and visibility. Effective guards minimize exposure to punches, particularly hooks and uppercuts, by aligning the upper body in ways that leverage natural biomechanics for protection and mobility.[8][9] The standard or conventional guard, also known as the traditional guard, positions both fists at cheek level with the lead hand slightly extended and off-center, approximately 4-6 inches from the face, while the rear hand rests near the rear cheek. Elbows are tucked inward to cover the ribs and midsection, and the chin is lowered behind the lead shoulder for added protection. This setup allows for clear line of sight over the lead glove and facilitates parrying or blocking straight punches and hooks. It is versatile for various fighting ranges and suits out-boxers or boxer-punchers who prioritize distance control.[9][8][10] The Philly Shell guard, sometimes called the shoulder roll or crab shell, involves dropping the lead hand low to cover the abdomen while the rear hand hovers near the lead cheek or jawline. The lead shoulder is rolled forward to deflect incoming crosses, creating a layered defense that relies on shoulder rotation rather than arm extension. Popularized by Floyd Mayweather, this guard provides unobstructed vision and enables quick counters, particularly jabs from the rear hand, but demands exceptional reflexes and timing to avoid vulnerability against southpaw opponents or aggressive body attacks. It is best suited for agile fighters with strong core stability.[8][9][11] The peek-a-boo guard features both hands raised high, with fists pressed against the cheeks or temples and elbows flared slightly to guard the body, forming a compact shell around the head. The shoulders are squared, and the chin tucks deeply, emphasizing constant head bobbing and weaving for evasion. Developed by trainer Cus D'Amato and mastered by Mike Tyson, this guard excels in close-range infighting, neutralizing height disadvantages for shorter boxers by facilitating explosive forward pressure and angle changes. However, it can limit downward visibility and expose the body to uppercuts if head movement falters.[8][12][13] Variations of guards adapt to fighter physique and strategy, such as the high guard, where hands are positioned at temple level with palms facing inward to create a "tunnel" of protection for the head, often paired with squared shoulders for aggressive advances. This suits compact, muscular body types like swarmers but drains energy over long rounds and leaves the midsection open, making it less ideal for taller frames prone to body shots. Conversely, the low or half guard lowers the lead hand below the beltline while keeping the rear hand elevated, offering superior vision and jab concealment for lanky out-boxers, though it risks exposing the head and requires precise footwork to compensate— a mismatch for stockier builds vulnerable to overhead strikes.[9][8] Biomechanically, guards enhance defensive efficacy by optimizing joint angles and muscle engagement; for instance, the standard guard's elbow positioning distributes impact forces across the torso, reducing rotational strain on the spine, while the peek-a-boo's high hands promote lateral head slips that leverage neck and shoulder flexors for fluid evasion without compromising balance. The Philly Shell utilizes shoulder abduction to absorb linear impacts, minimizing arm fatigue and preserving punch velocity during transitions. These configurations maintain forward-facing posture for unobstructed targeting and quick arm extension, integrating seamlessly with orthodox or southpaw stances to support blocking hooks via raised shoulders.[9][8][12]Footwork

The bounce step, professionally termed the bounce step or pendulum step, refers to the light bouncing movement on the balls of the feet integral to boxing footwork. It utilizes foot bounce to maintain a flexible center of gravity, enabling quick adjustments in distance, initiation of attacks or dodges, and preservation of balance and rhythm. As a core element, it integrates with stances and guards to facilitate dynamic mobility and defensive positioning.[14]Punching Techniques

Basic Punches