Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

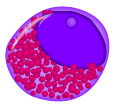

Promyelocyte

View on Wikipedia

| Promyelocyte | |

|---|---|

Promyelocyte from bone marrow examination | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | Myeloblast |

| Gives rise to | Myelocyte |

| Location | Bone marrow |

| Identifiers | |

| TH | H2.00.04.3.04003 |

| Anatomical terms of microanatomy | |

A promyelocyte (or progranulocyte) is a granulocyte precursor, developing from the myeloblast and developing into the myelocyte. Promyelocytes measure 12–20 microns in diameter. The nucleus of a promyelocyte is approximately the same size as a myeloblast but their cytoplasm is much more abundant.[1] They also have less prominent nucleoli than myeloblasts and their chromatin is more coarse and clumped.[1] The cytoplasm is basophilic and contains primary red/purple granules.[2]

Differentiation

[edit]The differentiation of promyelocytes from hematopoietic stem cells is regulated by various growth factors, cytokines, and transcription factors, that ensure the balanced production of white blood cells for proper immune function.[3] Promyelocytes play a critical role in hematopoiesis by serving as an intermediate in the differentiation pathway leading to mature granulocytes (Hematopoiesis image below). This process involves a series of steps, including proliferation, differentiation, and maturation.[4]

Function

[edit]The function of promyelocytes are closely linked to their differentiation into mature granulocytes, which include neutrophils, eosinophils, and basophils.[citation needed] These functions are essential for innate immunity and host defense mechanisms, including phagocytosis, inflammation, and immune surveillance.

Clinical significance

[edit]Abnormalities in promyelocyte development or function can have significant clinical implications, leading to various hematologic disorders. Some of the notable conditions associated with promyelocytes include acute promyeloytic leukemia, myelodysplastic syndromes and infections/inflammatory conditions.[5]

Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia (APL) is a subtype of Acute Myeloid Leukemia, known for its accumulation of abnormal, course, densely granulated promyelocytes in the bone marrow.[6] The excessive proliferation of promyelocytes, attributing at least 30% of the myeloid cells in the bone marrow, result in a depletion of blood cells, including white blood cells, red blood cells, and platelets.[7][8] This variation is also called 'hypergranual' APL, as hypergranual promyelocytes are characterized by the dense azurophilic granule concentrations in the cytoplasm.[citation needed] APL is often associated with a specific chromosomal translocation involving the retinoic acid receptor alpha (RARα) gene on chromosome 17 and the promyelocytic leukemia gene on chromosome 15.[9]

In a less common variation of APL, called hypogranual APL, patients present with leukocytosis in addition to the excessive abnormal promyelocyte concentration. The cells in hypogranual APL have an irregular nucleus with finer granulation than the typical hypergranual APL.[10]

Treatment of APL involves a three phase regiment: induction phase, consolidation phase, and maintenance phase. The induction phase serves to put APL in remission by reducing the number of leukemic cells and lasts approximately two months. This involves the use of all trans-retinoic acid (ATRA) in combination with arsenic trioxide (ATO), chemotherapy, or chemotherapy plus ATO. The consolidation phase is intended to keep the patient in remission and destroy any remaining leukemic cells. This phase lasts several months and involves the use of ATRA plus ATO, ATRA plus chemotherapy, or chemotherapy alone. The last stage, the maintenance stage, uses a lower dosage of drugs to decrease the risk of patient relapse, and lasts approximately a year.[11]

Myelodysplastic Syndromes (MDS) are a group of disorders characterized by ineffective hematopoiesis or dysplasia changes in some myeloid lineages of the bone marrow. Abnormalities in promyelocyte maturation may contribute to pathogenesis of MDS and its associated complications.[5] These associated complications may include anemia, recurrent infections, excessive bleeding and an increased risk of cancer of the bone marrow/blood cells (leukemia).[12] Treatment of MDS is used to slow the disease, and involves blood transfusions, medications, and bone marrow transplants. There is currently no cure for MDS.

The assessment of promyelocytes and their derivatives is an essential component of the diagnosis of various hematologic disorders. Laboratory test commonly used to evaluate promyelocyte abnormalities include complete blood count (CBC), morphologic evaluation of peripheral blood smears, flow cytometry, and cytogenetic analysis, including bone marrow biopsies with aspirate.[13]

Promyelocytes are essential players in the body's immune system, serving as precursors to mature granulocytes involved in host defense and inflammatory responses. Understanding the characteristics, functions, and clinical significance of promyeloctes is crucial for the diagnosis, management, and treatment of various hematologic disorders.

Additional images

[edit]-

Bone marrow smear from a patient with acute promyelocytic leukemia, showing characteristic abnormal promyelocytes.[14]

-

Hematopoiesis

-

Basophilic promyelocyte

-

Eosinophilic promyelocyte

-

Neutrophilic promyelocyte

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Promyelocyte – LabCE.com, Laboratory Continuing Education". www.labce.com. Retrieved 2018-11-21.

- ^ "Promyelocyte". imagebank.hematology.org. Retrieved 2024-03-06.

- ^ Whetton AD, Dexter TM (December 1993). "Influence of growth factors and substrates on differentiation of haemopoietic stem cells". Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 5 (6): 1044–1049. doi:10.1016/0955-0674(93)90090-D. PMID 8129942.

- ^ Jagannathan-Bogdan M, Zon LI (June 2013). "Hematopoiesis". Development. 140 (12): 2463–2467. doi:10.1242/dev.083147. PMC 3666375. PMID 23715539.

- ^ a b Vanegas YA, Azzouqa AM, Menke DM, Foran JM, Vishnu P (September 2018). "Myelodysplasia-related acute myeloid leukemia and acute promyelocytic leukemia: concomitant occurrence of two molecularly distinct diseases". Hematology Reports. 10 (3): 7658. doi:10.4081/hr.2018.7658. PMC 6151345. PMID 30283621.

- ^ To M, Villatoro V (2019-06-27). "Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia (APL)". A Laboratory Guide to Clinical Hematology.

- ^ "Acute promyelocytic leukemia: MedlinePlus Genetics". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 2024-03-06.

- ^ Ryan MM (March 2018). "Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia: A Summary". Journal of the Advanced Practitioner in Oncology. 9 (2): 178–187. PMC 6303006. PMID 30588352.

- ^ Liquori A, Ibañez M, Sargas C, Sanz MÁ, Barragán E, Cervera J (March 2020). "Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia: A Constellation of Molecular Events around a Single PML-RARA Fusion Gene". Cancers. 12 (3): 624. doi:10.3390/cancers12030624. PMC 7139833. PMID 32182684.

- ^ "Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia: A Review and Discussion of Variant Translocations". meridian.allenpress.com. Retrieved 2024-03-10.

- ^ "Treatment of Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia (APL)". www.cancer.org. Retrieved 2024-04-12.

- ^ "Myelodysplastic syndromes - Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 2024-04-12.

- ^ "Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia (APL) Workup: Approach Considerations, Laboratory Studies, Other Tests". emedicine.medscape.com. Retrieved 2024-04-12.

- ^ Image by Mikael Häggström, MD. Reference for findings: Syed Zaidi, M.D. "APL with PML-RARA". APL with PML-RARA. Last author update: 1 February 2013

Source image: File:Faggot cell in AML-M3.jpg from PEIR Digital Library (Pathology image database) (Public Domain)

External links

[edit]- Histology image: 01806loa – Histology Learning System at Boston University – "18. Bone Marrow and Hemopoiesis: bone marrow smear, promyelocyte and erythroblasts "

- Histology at KUMC blood-blood08 "Bone marrow"

- Histology at KUMC blood-blood11 "Bone marrow"

- "White Cell Basics: Maturation" at virginia.edu

- Histology image: 75_02 at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center – "Bone marrow smear"

- Promyelocyte at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

![Bone marrow smear from a patient with acute promyelocytic leukemia, showing characteristic abnormal promyelocytes.[14]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/ec/Cytology_of_acute_promyelocytic_leukemia%2C_annotated.png/120px-Cytology_of_acute_promyelocytic_leukemia%2C_annotated.png)