Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Monocyte

View on Wikipedia| Monocyte | |

|---|---|

3D rendering of a monocyte | |

| |

| Details | |

| System | Immune system |

| Identifiers | |

| MeSH | D009000 |

| TH | H2.00.04.1.02010 |

| FMA | 62864 |

| Anatomical terms of microanatomy | |

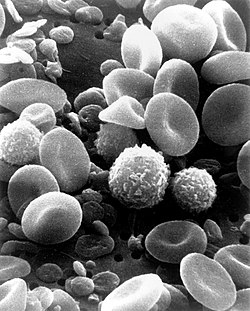

Monocytes are a type of leukocyte or white blood cell. They are the largest type of leukocyte in the blood and can differentiate into macrophages and monocyte-derived dendritic cells. As a part of the vertebrate innate immune system monocytes also influence adaptive immune responses and exert tissue repair functions. There are at least three subclasses of monocytes in human blood based on their phenotypic receptors.

Structure

[edit]Monocytes are amoeboid in appearance, and have nongranulated cytoplasm.[1] Thus they are classified as agranulocytes, although they might occasionally display some azurophil granules and/or vacuoles. With a diameter of 15–22 μm, monocytes are the largest cell type in peripheral blood.[2][3] Monocytes are mononuclear cells and the ellipsoidal nucleus is often lobulated/indented, causing a bean-shaped or kidney-shaped appearance.[4] Monocytes compose 2% to 10% of all leukocytes in the human body.

Development

[edit]

Monocytes are produced by the bone marrow from precursors called monoblasts, bipotent cells that differentiated from hematopoietic stem cells.[5] Monocytes circulate in the bloodstream for about one to three days and then typically migrate into organs throughout the body where they differentiate into macrophages and dendritic cells.

Subpopulations

[edit]In humans

[edit]The first clear description of monocyte subsets by flow cytometry dates back to the late 1980s, when a population of CD16-positive monocytes was described.[6][7] Today, three types of monocytes are recognized in human blood:[8]

- The classical monocyte is characterized by high level expression of the CD14 cell surface receptor (CD14++ CD16− monocyte)

- The non-classical monocyte shows low level expression of CD14 and additional co-expression of the CD16 receptor (CD14+CD16++ monocyte).[9]

- The intermediate monocyte expresses high levels of CD14 and low levels of CD16 (CD14++CD16+ monocytes).

While in humans the level of CD14 expression can be used to differentiate non-classical and intermediate monocytes, the slan (6-Sulfo LacNAc) cell surface marker was shown to give an unequivocal separation of the two cell types.[10][11]

Ghattas et al. state that the "intermediate" monocyte population is likely to be a unique subpopulation of monocytes, as opposed to a developmental step, due to their comparatively high expression of surface receptors involved in reparative processes (including vascular endothelial growth factor receptors type 1 and 2, CXCR4, and Tie-2) as well as evidence that the "intermediate" subset is specifically enriched in the bone marrow.[12]

In mice

[edit]In mice, monocytes can be divided in two subpopulations. Inflammatory monocytes (CX3CR1low, CCR2pos, Ly6Chigh, PD-L1neg), which are equivalent to human classical CD14++ CD16− monocytes and resident monocytes (CX3CR1high, CCR2neg, Ly6Clow, PD-L1pos), which are equivalent to human non-classical CD14+ CD16+ monocytes. Resident monocytes have the ability to patrol along the endothelium wall in the steady state and under inflammatory conditions.[13][14][15][16]

Function

[edit]Monocytes are mechanically active cells[17] and migrate from blood to an inflammatory site to perform their functions. As explained before, they can differentiate into macrophages and dendritic cells, but the different monocyte subpopulations can also exert specific functions on their own. In general, monocytes and their macrophage and dendritic cell progeny serve three main functions in the immune system. These are phagocytosis, antigen presentation, and cytokine production. Phagocytosis is the process of uptake of microbes and particles followed by digestion and destruction of this material. Monocytes can perform phagocytosis using intermediary (opsonising) proteins such as antibodies or complement that coat the pathogen, as well as by binding to the microbe directly via pattern recognition receptors that recognize pathogens. Monocytes are also capable of killing infected host cells via antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity. Vacuolization may be present in a cell that has recently phagocytized foreign matter.

Differentiation into other effector cells

[edit]Monocytes can migrate into tissues and replenish resident macrophage populations. Macrophages have a high antimicrobial and phagocytic activity and thereby protect tissues from foreign substances. They are cells that possess a large smooth nucleus, a large area of cytoplasm, and many internal vesicles for processing foreign material. Although they can be derived from monocytes, a large proportion is already formed prenatally in the yolk sac and foetal liver.[18]

In vitro, monocytes can differentiate into dendritic cells by adding the cytokines granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and interleukin 4.[19] Such monocyte-derived cells do, however, retain the signature of monocytes in their transcriptome and they cluster with monocytes and not with bona fide dendritic cells.[20]

Specific functions of monocyte subpopulations

[edit]

Aside from their differentiation capacity, monocytes can also directly regulate immune responses. As explained before, they are able to perform phagocytosis. Cells of the classical subpopulation are the most efficient phagocytes and can additionally secrete inflammation-stimulating factors. The intermediate subpopulation is important for antigen presentation and T lymphocyte stimulation.[21] Briefly, antigen presentation describes a process during which microbial fragments that are present in the monocytes after phagocytosis are incorporated into MHC molecules. They are then trafficked to the cell surface of the monocytes (or macrophages or dendritic cells) and presented as antigens to activate T lymphocytes, which then mount a specific immune response against the antigen. Non-classical monocytes produce high amounts of pro-inflammatory cytokines like tumor necrosis factor and interleukin-12 after stimulation with microbial products. Furthermore, a monocyte patrolling behavior has been demonstrated in humans both for the classical and the non-classical monocytes, meaning that they slowly move along the endothelium to examine it for pathogens.[22] Said et al. showed that activated monocytes express high levels of PD-1 which might explain the higher expression of PD-1 in CD14+CD16++ monocytes as compared to CD14++CD16− monocytes. Triggering monocytes-expressed PD-1 by its ligand PD-L1 induces IL-10 production, which activates CD4 Th2 cells and inhibits CD4 Th1 cell function.[23] Many factors produced by other cells can regulate the chemotaxis and other functions of monocytes. These factors include most particularly chemokines such as monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (CCL2) and monocyte chemotactic protein-3 (CCL7); certain arachidonic acid metabolites such as leukotriene B4 and members of the 5-hydroxyicosatetraenoic acid and 5-oxo-eicosatetraenoic acid family of OXE1 receptor agonists (e.g., 5-HETE and 5-oxo-ETE); and N-Formylmethionine leucyl-phenylalanine and other N-formylated oligopeptides which are made by bacteria and activate the formyl peptide receptor 1.[24] Other microbial products can directly activate monocytes and this leads to production of pro-inflammatory and, with some delay, of anti-inflammatory cytokines. Typical cytokines produced by monocytes are TNF, IL-1, and IL-12.

Clinical significance

[edit]

A monocyte count is part of a complete blood count and is expressed either as a percentage of monocytes among all white blood cells or as absolute numbers. Both may be useful, but these cells became valid diagnostic tools only when monocyte subsets are determined. Monocytic cells may contribute to the severity and disease progression in COVID-19 patients.[25]

Monocytosis

[edit]Monocytosis is the state of excess monocytes in the peripheral blood. It may be indicative of various disease states. Examples of processes that can increase a monocyte count include:

- chronic inflammation

- diabetes[26]

- stress response[27]

- Cushing's syndrome (hyperadrenocorticism)

- immune-mediated disease

- granulomatous disease

- atherosclerosis[28]

- necrosis

- red blood cell regeneration

- viral fever

- sarcoidosis

- chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML)

- Resolution of fasting[29]

A high count of CD14+CD16++ monocytes is found in severe infection (sepsis).[30]

In the field of atherosclerosis, high numbers of the CD14++CD16+ intermediate monocytes were shown to be predictive of cardiovascular events in populations at risk.[31][32]

CMML is characterized by a persistent monocyte count of > 1000/microL of blood. Analysis of monocyte subsets has demonstrated predominance of classical monocytes and absence of CD14lowCD16+ monocytes.[33][34] The absence of non-classical monocytes can assist in diagnosis of the disease and the use of slan as a marker can improve specificity.[35]

Monocytopenia

[edit]Monocytopenia is a form of leukopenia associated with a deficiency of monocytes. A very low count of these cells is found after therapy with immuno-suppressive glucocorticoids.[36]

Also, non-classical slan+ monocytes are strongly reduced in patients with hereditary diffuse leukoencephalopathy with spheroids, a neurologic disease associated with mutations in the macrophage colony-stimulating factor receptor gene.[10]

Blood content

[edit]

See also

[edit]Further reading

[edit]- Jakubzick, C. V., Randolph, G. J., & Henson, P. M. (2017). Monocyte differentiation and antigen-presenting functions. In: Nature Reviews Immunology. doi:10.1038/nri.2017.28

References

[edit]- ^ Nichols, Barbara A.; Bainton, Dorothy Ford; Farquhar, Marilyn G. (1 August 1971). "Differentiation of monocytes". Journal of Cell Biology. 50 (2): 498–515. doi:10.1083/jcb.50.2.498. PMC 2108281. PMID 4107019.

- ^ Palmer, L.; Briggs, C.; McFadden, S.; Zini, G.; Burthem, J.; Rozenberg, G.; Proytcheva, M.; Machin, S. J. (2015). "ICSH recommendations for the standardization of nomenclature and grading of peripheral blood cell morphological features". International Journal of Laboratory Hematology. 37 (3): 287–303. doi:10.1111/ijlh.12327. ISSN 1751-5521. PMID 25728865.

- ^ Steve, Paxton; Michelle, Peckham; Adele, Knibbs (28 April 2018). "The Leeds Histology Guide". leeds.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 28 April 2018.

- ^ Zini, Gina (2021). "How I investigate difficult cells at the optical microscope". International Journal of Laboratory Hematology. 43 (3): 346–353. doi:10.1111/ijlh.13437. ISSN 1751-5521. PMID 33342036.

- ^ Monga I, Kaur K, Dhanda S (March 2022). "Revisiting hematopoiesis: applications of the bulk and single-cell transcriptomics dissecting transcriptional heterogeneity in hematopoietic stem cells". Briefings in Functional Genomics. 21 (3): 159–176. doi:10.1093/bfgp/elac002. PMID 35265979.

- ^ Ziegler-Heitbrock, H W Loems; Passlick, Bernward; Flieger, Dimitri (December 1988). "The Monoclonal Antimonocyte Antibody My4 Stains B Lymphocytes and Two Distinct Monocyte Subsets in Human Peripheral Blood". Hybridoma. 7 (6): 521–527. doi:10.1089/hyb.1988.7.521. PMID 2466760.

- ^ Passlick, Bernward; Flieger, Dimitri; Ziegler-Heitbrock, H W Loems (November 1989). "Characterization of a human monocyte subpopulation coexpressing CD14 and CD16 antigens". Blood. 74 (7): 2527–2534. doi:10.1182/blood.V74.7.2527.2527. PMID 2478233.

- ^ Ziegler-Heitbrock, Loems; Ancuta, Petronela; Crowe, Suzanne; Dalod, Marc; Grau, Veronika; Hart, Derek N.; Leenen, Pieter J. M.; Liu, Yong-Jun; MacPherson, Gordon; Randolph, Gwendalyn J.; Scherberich, Juergen; Schmitz, Juergen; Shortman, Ken; Sozzani, Silvano; Strobl, Herbert; Zembala, Marek; Austyn, Jonathan M.; Lutz, Manfred B. (21 October 2010). "Nomenclature of monocytes and dendritic cells in blood". Blood. 116 (16): e74 – e80. doi:10.1182/blood-2010-02-258558. hdl:11379/41075. PMID 20628149. S2CID 1570404.

- ^ Ziegler-Heitbrock, Loems (March 2007). "The CD14+ CD16+ blood monocytes: their role in infection and inflammation". Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 81 (3): 584–592. doi:10.1189/jlb.0806510. PMID 17135573. S2CID 31534841.

- ^ a b Hofer, Thomas P.; Zawada, Adam M.; Frankenberger, Marion; Skokann, Kerstin; Satzl, Anna A.; Gesierich, Wolfgang; Schuberth, Madeleine; Levin, Johannes; Danek, Adrian; Rotter, Björn; Heine, Gunnar H.; Ziegler-Heitbrock, Loems (10 December 2015). "slan-defined subsets of CD16-positive monocytes: impact of granulomatous inflammation and M-CSF receptor mutation". Blood. 126 (24): 2601–2610. doi:10.1182/blood-2015-06-651331. PMID 26443621.

- ^ Hofer, Thomas P.; van de Loosdrecht, Arjan A.; Stahl-Hennig, Christiane; Cassatella, Marco A.; Ziegler-Heitbrock, Loems (13 September 2019). "6-Sulfo LacNAc (Slan) as a Marker for Non-classical Monocytes". Frontiers in Immunology. 10: 2052. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.02052. PMC 6753898. PMID 31572354.

- ^ Ghattas, Angie; Griffiths, Helen R.; Devitt, Andrew; Lip, Gregory Y.H.; Shantsila, Eduard (October 2013). "Monocytes in Coronary Artery Disease and Atherosclerosis". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 62 (17): 1541–1551. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2013.07.043. PMID 23973684.

- ^ Carlin, Leo M.; Stamatiades, Efstathios G.; Auffray, Cedric; Hanna, Richard N.; Glover, Leanne; Vizcay-Barrena, Gema; Hedrick, Catherine C.; Cook, H. Terence; Diebold, Sandra; Geissmann, Frederic (April 2013). "Nr4a1-Dependent Ly6Clow Monocytes Monitor Endothelial Cells and Orchestrate Their Disposal". Cell. 153 (2): 362–375. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.010. PMC 3898614. PMID 23582326.

- ^ Auffray, Cedric; Fogg, Darin; Garfa, Meriem; Elain, Gaelle; Join-Lambert, Olivier; Kayal, Samer; Sarnacki, Sabine; Cumano, Ana; Lauvau, Gregoire; Geissmann, Frederic (3 August 2007). "Monitoring of Blood Vessels and Tissues by a Population of Monocytes with Patrolling Behavior". Science. 317 (5838): 666–670. Bibcode:2007Sci...317..666A. doi:10.1126/science.1142883. PMID 17673663. S2CID 46067303.

- ^ Imhof, Beat A.; Jemelin, Stephane; Ballet, Romain; Vesin, Christian; Schapira, Marc; Karaca, Melis; Emre, Yalin (16 August 2016). "CCN1/CYR61-mediated meticulous patrolling by Ly6C low monocytes fuels vascular inflammation". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 113 (33): E4847 – E4856. Bibcode:2016PNAS..113E4847I. doi:10.1073/pnas.1607710113. PMC 4995973. PMID 27482114.

- ^ Bianchini, Mariaelvy; Duchêne, Johan; Santovito, Donato; Schloss, Maximilian J.; Evrard, Maximilien; Winkels, Holger; Aslani, Maria; Mohanta, Sarajo K.; Horckmans, Michael; Blanchet, Xavier; Lacy, Michael; von Hundelshausen, Philipp; Atzler, Dorothee; Habenicht, Andreas; Gerdes, Norbert; Pelisek, Jaroslav; Ng, Lai Guan; Steffens, Sabine; Weber, Christian; Megens, Remco T. A. (21 June 2019). "PD-L1 expression on nonclassical monocytes reveals their origin and immunoregulatory function". Science Immunology. 4 (36) eaar3054. doi:10.1126/sciimmunol.aar3054. PMID 31227596. S2CID 195259881.

- ^ Evers, Tom M.J.; Sheikhhassani, Vahid; Haks, Mariëlle C.; Storm, Cornelis; Ottenhoff, Tom H.M.; Mashaghi, Alireza (2022). "Single-cell analysis reveals chemokine-mediated differential regulation of monocyte mechanics". iScience. 25 (1) 103555. Bibcode:2022iSci...25j3555E. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2021.103555. PMC 8693412. PMID 34988399.

- ^ Murphy, Kenneth; Weaver, Casey (2018). "Grundbegriffe der Immunologie". Janeway Immunologie (in German). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg. pp. 3–46. doi:10.1007/978-3-662-56004-4_1. ISBN 978-3-662-56003-7. PMC 7844863.

- ^ Sallusto, F; Cella, M; Danieli, C; Lanzavecchia, A (1 August 1995). "Dendritic cells use macropinocytosis and the mannose receptor to concentrate macromolecules in the major histocompatibility complex class II compartment: downregulation by cytokines and bacterial products". Journal of Experimental Medicine. 182 (2): 389–400. doi:10.1084/jem.182.2.389. PMC 2192110. PMID 7629501.

- ^ Robbins, Scott H; Walzer, Thierry; Dembélé, Doulaye; Thibault, Christelle; Defays, Axel; Bessou, Gilles; Xu, Huichun; Vivier, Eric; Sellars, MacLean; Pierre, Philippe; Sharp, Franck R; Chan, Susan; Kastner, Philippe; Dalod, Marc (2008). "Novel insights into the relationships between dendritic cell subsets in human and mouse revealed by genome-wide expression profiling". Genome Biology. 9 (1): R17. doi:10.1186/gb-2008-9-1-r17. PMC 2395256. PMID 18218067.

- ^ Wong, Kok Loon; Tai, June Jing-Yi; Wong, Wing-Cheong; Han, Hao; Sem, Xiaohui; Yeap, Wei-Hseun; Kourilsky, Philippe; Wong, Siew-Cheng (2011-08-04). "Gene expression profiling reveals the defining features of the classical, intermediate, and nonclassical human monocyte subsets". Blood. 118 (5): e16 – e31. doi:10.1182/blood-2010-12-326355. ISSN 0006-4971. PMID 21653326.

- ^ Collison, Joanna L.; Carlin, Leo M.; Eichmann, Martin; Geissmann, Frederic; Peakman, Mark (1 August 2015). "Heterogeneity in the Locomotory Behavior of Human Monocyte Subsets over Human Vascular Endothelium In Vitro". The Journal of Immunology. 195 (3): 1162–1170. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1401806. PMID 26085686.

- ^ Said, Elias A; Dupuy, Franck P; Trautmann, Lydie; Zhang, Yuwei; Shi, Yu; El-Far, Mohamed; Hill, Brenna J; Noto, Alessandra; Ancuta, Petronela; Peretz, Yoav; Fonseca, Simone G; Van Grevenynghe, Julien; Boulassel, Mohamed R; Bruneau, Julie; Shoukry, Naglaa H; Routy, Jean-Pierre; Douek, Daniel C; Haddad, Elias K; Sekaly, Rafick-Pierre (April 2010). "Programmed death-1–induced interleukin-10 production by monocytes impairs CD4+ T cell activation during HIV infection". Nature Medicine. 16 (4): 452–459. doi:10.1038/nm.2106. PMC 4229134. PMID 20208540.

- ^ Sozzani, S.; Zhou, D.; Locati, M.; Bernasconi, S.; Luini, W.; Mantovani, A.; O'Flaherty, J. T. (15 November 1996). "Stimulating properties of 5-oxo-eicosanoids for human monocytes: synergism with monocyte chemotactic protein-1 and -3". The Journal of Immunology. 157 (10): 4664–4671. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.157.10.4664. PMID 8906847. S2CID 23499393.

- ^ Gómez-Rial, Jose; Rivero-Calle, Irene; Salas, Antonio; Martinón-Torres, Federico (22 July 2020). "Role of Monocytes/Macrophages in Covid-19 Pathogenesis: Implications for Therapy". Infection and Drug Resistance. 13: 2485–2493. doi:10.2147/IDR.S258639. PMC 7383015. PMID 32801787.

- ^ Hoyer, FF; Zhang, X; Coppin, E; Vasamsetti, SB; Modugu, G; Schloss, MJ; Rohde, D; McAlpine, CS; Iwamoto, Y; Libby, P; Naxerova, K; Swirski, F; Dutta, P; Nahrendorf, P (April 2020). "Bone Marrow Endothelial Cells Regulate Myelopoiesis in Diabetes". Circulation. 142 (3): 244–258. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.046038. PMC 7375017. PMID 32316750.

- ^ Heidt, Timo; Sager, Hendrik B; Courties, Gabriel; Dutta, Partha; Iwamoto, Yoshiko; Zaltsman, Alex; von zur Muhlen, Constantin; Bode, Christoph; Fricchione, Gregory L; Denninger, John; Lin, Charles P; Vinegoni, Claudio; Libby, Peter; Swirski, Filip K; Weissleder, Ralph; Nahrendorf, Matthias (July 2014). "Chronic variable stress activates hematopoietic stem cells". Nature Medicine. 20 (7): 754–758. doi:10.1038/nm.3589. PMC 4087061. PMID 24952646.

- ^ Swirski, Filip K.; Libby, Peter; Aikawa, Elena; Alcaide, Pilar; Luscinskas, F. William; Weissleder, Ralph; Pittet, Mikael J. (2 January 2007). "Ly-6Chi monocytes dominate hypercholesterolemia-associated monocytosis and give rise to macrophages in atheromata". Journal of Clinical Investigation. 117 (1): 195–205. doi:10.1172/JCI29950. PMC 1716211. PMID 17200719.

- ^ O'Brien, Conan J.O.; Domingos, Ana I. (2023). "Old and "hangry" monocytes turn from friend to foe under assault". Immunity. 56 (4): 747–749. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2023.03.013. PMID 37044065.

- ^ Fingerle, G; Pforte, A; Passlick, B; Blumenstein, M; Strobel, M; Ziegler- Heitbrock, Hw (15 November 1993). "The novel subset of CD14+/CD16+ blood monocytes is expanded in sepsis patients". Blood. 82 (10): 3170–3176. doi:10.1182/blood.v82.10.3170.3170. PMID 7693040.

- ^ Heine, G.H.; Ulrich, C.; Seibert, E.; Seiler, S.; Marell, J.; Reichart, B.; Krause, M.; Schlitt, A.; Köhler, H.; Girndt, M. (March 2008). "CD14++CD16+ monocytes but not total monocyte numbers predict cardiovascular events in dialysis patients". Kidney International. 73 (5): 622–629. doi:10.1038/sj.ki.5002744. PMID 18160960.

- ^ Rogacev, Kyrill S.; Cremers, Bodo; Zawada, Adam M.; Seiler, Sarah; Binder, Nadine; Ege, Philipp; Große-Dunker, Gunnar; Heisel, Isabel; Hornof, Florian; Jeken, Jana; Rebling, Niko M.; Ulrich, Christof; Scheller, Bruno; Böhm, Michael; Fliser, Danilo; Heine, Gunnar H. (October 2012). "CD14++CD16+ Monocytes Independently Predict Cardiovascular Events". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 60 (16): 1512–1520. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2012.07.019. PMID 22999728.

- ^ Vuckovic, S.; Fearnley, D. B.; Gunningham, S.; Spearing, R. L.; Patton, W. N.; Hart, D. N. J. (June 1999). "Dendritic cells in chronic myelomonocytic leukaemia: Dendritic Cells in CMML". British Journal of Haematology. 105 (4): 974–985. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2141.1999.01431.x. PMID 10554809. S2CID 22571555.

- ^ Selimoglu-Buet, Dorothée; Wagner-Ballon, Orianne; Saada, Véronique; Bardet, Valérie; Itzykson, Raphaël; Bencheikh, Laura; Morabito, Margot; Met, Elisabeth; Debord, Camille; Benayoun, Emmanuel; Nloga, Anne-Marie; Fenaux, Pierre; Braun, Thorsten; Willekens, Christophe; Quesnel, Bruno; Adès, Lionel; Fontenay, Michaela; Rameau, Philippe; Droin, Nathalie; Koscielny, Serge; Solary, Eric (4 June 2015). "Characteristic repartition of monocyte subsets as a diagnostic signature of chronic myelomonocytic leukemia". Blood. 125 (23): 3618–3626. doi:10.1182/blood-2015-01-620781. PMC 4497970. PMID 25852055.

- ^ Tarfi, Sihem; Badaoui, Bouchra; Freynet, Nicolas; Morabito, Margot; Lafosse, Jeffie; Toma, Andréa; Etienne, Gabriel; Micol, Jean-Baptiste; Sloma, Ivan; Fenaux, Pierre; Solary, Eric; Selimoglu-Buet, Dorothée; Wagner-Ballon, Orianne (April 2020). "Disappearance of slan-positive non-classical monocytes for diagnosis of chronic myelomonocytic leukemia with an associated inflammatory state". Haematologica. 105 (4): e147 – e152. doi:10.3324/haematol.2019.219782. PMID 31413091. S2CID 199663779.

- ^ Fingerle-Rowson, G; Angstwurm, M; Andreesen, R; Ziegler-Heitbrock, HW (June 1998). "Selective depletion of CD14 + CD16 + monocytes by glucocorticoid therapy: Depletion of CD14+ CD16+ monocytes by glucocorticoids". Clinical & Experimental Immunology. 112 (3): 501–506. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00617.x. PMC 1904988. PMID 9649222.

External links

[edit]- Histology image: 01702ooa – Histology Learning System at Boston University

- Human Monocytes — Prof. Dr. Ziegler-Heitbrock

- Circulation of Body Fluids

.png/250px-Blausen_0649_Monocyte_(crop).png)

.png)