Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

RNA polymerase

View on Wikipedia

This article may be too technical for most readers to understand. (September 2010) |

| DNA-directed RNA polymerase | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| EC no. | 2.7.7.6 | ||||||||

| CAS no. | 9014-24-8 | ||||||||

| Databases | |||||||||

| IntEnz | IntEnz view | ||||||||

| BRENDA | BRENDA entry | ||||||||

| ExPASy | NiceZyme view | ||||||||

| KEGG | KEGG entry | ||||||||

| MetaCyc | metabolic pathway | ||||||||

| PRIAM | profile | ||||||||

| PDB structures | RCSB PDB PDBe PDBsum | ||||||||

| Gene Ontology | AmiGO / QuickGO | ||||||||

| |||||||||

In molecular biology, RNA polymerase (abbreviated RNAP or RNApol), or more specifically DNA-directed/dependent RNA polymerase (DdRP), is an enzyme that catalyzes the chemical reactions that synthesize RNA from a DNA template.

Using the enzyme helicase, RNAP locally opens the double-stranded DNA so that one strand of the exposed nucleotides can be used as a template for the synthesis of RNA, a process called transcription. A transcription factor and its associated transcription mediator complex must be attached to a DNA binding site called a promoter region before RNAP can initiate the DNA unwinding at that position. RNAP not only initiates RNA transcription, it also guides the nucleotides into position, facilitates attachment and elongation, has intrinsic proofreading and replacement capabilities, and termination recognition capability. In eukaryotes, RNAP can build chains as long as 2.4 million nucleotides.

RNAP produces RNA that, functionally, is either for protein coding, i.e. messenger RNA (mRNA); or non-coding (so-called "RNA genes"). Examples of four functional types of RNA genes are:

- Transfer RNA (tRNA)

- Transfers specific amino acids to growing polypeptide chains at the ribosomal site of protein synthesis during translation;

- Ribosomal RNA (rRNA)

- Incorporates into ribosomes;

- Micro RNA (miRNA)

- Regulates gene activity; and, RNA silencing

- Catalytic RNA (ribozyme)

- Functions as an enzymatically active RNA molecule.

RNA polymerase is essential to life, and is found in all living organisms and many viruses. Depending on the organism, a RNA polymerase can be a protein complex (multi-subunit RNAP) or only consist of one subunit (single-subunit RNAP, ssRNAP), each representing an independent lineage. The former is found in bacteria, archaea, and eukaryotes alike, sharing a similar core structure and mechanism.[1] The latter is found in phages as well as eukaryotic chloroplasts and mitochondria, and is related to modern DNA polymerases.[2] Eukaryotic and archaeal RNAPs have more subunits than bacterial ones do, and are controlled differently.

Bacteria and archaea only have one RNA polymerase. Eukaryotes have multiple types of nuclear RNAP, each responsible for synthesis of a distinct subset of RNA:

- RNA polymerase I synthesizes a pre-rRNA 45S (35S in yeast), which matures and will form the major RNA sections of the ribosome.

- RNA polymerase II synthesizes precursors of mRNAs and most sRNA and microRNAs.

- RNA polymerase III synthesizes tRNAs, rRNA 5S and other small RNAs found in the nucleus and cytosol.

- RNA polymerase IV and V found in plants are less understood; they make siRNA. In addition to the ssRNAPs, chloroplasts also encode and use a bacteria-like RNAP.

Structure

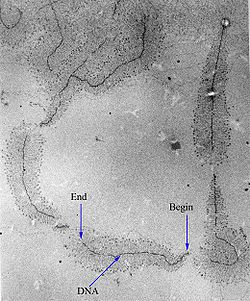

[edit]The 2006 Nobel Prize in Chemistry was awarded to Roger D. Kornberg for creating detailed molecular images of RNA polymerase during various stages of the transcription process.[3][4]

In most prokaryotes, a single RNA polymerase species transcribes all types of RNA. RNA polymerase "core" from E. coli consists of five subunits: two alpha (α) subunits of 36 kDa, a beta (β) subunit of 150 kDa, a beta prime subunit (β′) of 155 kDa, and a small omega (ω) subunit. A sigma (σ) factor binds to the core, forming the holoenzyme. After transcription starts, the factor can unbind and let the core enzyme proceed with its work.[5][6] The core RNA polymerase complex forms a "crab claw" or "clamp-jaw" structure with an internal channel running along the full length.[7] Eukaryotic and archaeal RNA polymerases have a similar core structure and work in a similar manner, although they have many extra subunits.[8]

All RNAPs contain metal cofactors, in particular zinc and magnesium cations which aid in the transcription process.[9][10]

Function

[edit]

Control of the process of gene transcription affects patterns of gene expression and, thereby, allows a cell to adapt to a changing environment, perform specialized roles within an organism, and maintain basic metabolic processes necessary for survival. Therefore, it is hardly surprising that the activity of RNAP is long, complex, and highly regulated. In Escherichia coli bacteria, more than 100 transcription factors have been identified, which modify the activity of RNAP.[11]

RNAP can initiate transcription at specific DNA sequences known as promoters. It then produces an RNA chain, which is complementary to the template DNA strand. The process of adding nucleotides to the RNA strand is known as elongation; in eukaryotes, RNAP can build chains as long as 2.4 million nucleotides (the full length of the dystrophin gene). RNAP will preferentially release its RNA transcript at specific DNA sequences encoded at the end of genes, which are known as terminators.

Products of RNAP include:

- Messenger RNA (mRNA)—template for the synthesis of proteins by ribosomes.

- Non-coding RNA or "RNA genes"—a broad class of genes that encode RNA that is not translated into protein. The most prominent examples of RNA genes are transfer RNA (tRNA) and ribosomal RNA (rRNA), both of which are involved in the process of translation. However, since the late 1990s, many new RNA genes have been found, and thus RNA genes may play a much more significant role than previously thought.

- Transfer RNA (tRNA)—transfers specific amino acids to growing polypeptide chains at the ribosomal site of protein synthesis during translation

- Ribosomal RNA (rRNA)—a component of ribosomes

- Micro RNA—regulates gene activity

- Catalytic RNA (Ribozyme)—enzymatically active RNA molecules

RNAP accomplishes de novo synthesis. It is able to do this because specific interactions with the initiating nucleotide hold RNAP rigidly in place, facilitating chemical attack on the incoming nucleotide. Such specific interactions explain why RNAP prefers to start transcripts with ATP (followed by GTP, UTP, and then CTP). In contrast to DNA polymerase, RNAP includes helicase activity, therefore no separate enzyme is needed to unwind DNA.

Action

[edit]Initiation

[edit]RNA polymerase binding in bacteria involves the sigma factor recognizing the core promoter region containing the −35 and −10 elements (located before the beginning of sequence to be transcribed) and also, at some promoters, the α subunit C-terminal domain recognizing promoter upstream elements.[12] There are multiple interchangeable sigma factors, each of which recognizes a distinct set of promoters. For example, in E. coli, σ70 is expressed under normal conditions and recognizes promoters for genes required under normal conditions ("housekeeping genes"), while σ32 recognizes promoters for genes required at high temperatures ("heat-shock genes"). In archaea and eukaryotes, the functions of the bacterial general transcription factor sigma are performed by multiple general transcription factors that work together. The RNA polymerase-promoter closed complex is usually referred to as the "transcription preinitiation complex."[13][14]

After binding to the DNA, the RNA polymerase switches from a closed complex to an open complex. This change involves the separation of the DNA strands to form an unwound section of DNA of approximately 13 bp, referred to as the "transcription bubble". Supercoiling plays an important part in polymerase activity because of the unwinding and rewinding of DNA. Because regions of DNA in front of RNAP are unwound, there are compensatory positive supercoils. Regions behind RNAP are rewound and negative supercoils are present.[14]

Promoter escape

[edit]RNA polymerase then starts to synthesize the initial DNA-RNA heteroduplex, with ribonucleotides base-paired to the template DNA strand according to Watson-Crick base-pairing interactions. As noted above, RNA polymerase makes contacts with the promoter region. However these stabilizing contacts inhibit the enzyme's ability to access DNA further downstream and thus the synthesis of the full-length product. In order to continue RNA synthesis, RNA polymerase must escape the promoter. It must maintain promoter contacts while unwinding more downstream DNA for synthesis, "scrunching" more downstream DNA into the initiation complex.[15] During the promoter escape transition, RNA polymerase is considered a "stressed intermediate." Thermodynamically the stress accumulates from the DNA-unwinding and DNA-compaction activities. Once the DNA-RNA heteroduplex is long enough (~10 bp), RNA polymerase releases its upstream contacts and effectively achieves the promoter escape transition into the elongation phase. The heteroduplex at the active center stabilizes the elongation complex.

However, promoter escape is not the only outcome. RNA polymerase can also relieve the stress by releasing its downstream contacts, arresting transcription. The paused transcribing complex has two options: (1) release the nascent transcript and begin anew at the promoter or (2) reestablish a new 3′-OH on the nascent transcript at the active site via RNA polymerase's catalytic activity and recommence DNA scrunching to achieve promoter escape. Abortive initiation, the unproductive cycling of RNA polymerase before the promoter escape transition, results in short RNA fragments of around 9 bp in a process known as abortive transcription. The extent of abortive initiation depends on the presence of transcription factors and the strength of the promoter contacts.[16]

Elongation

[edit]

The 17-bp transcriptional complex has an 8-bp DNA-RNA hybrid, that is, 8 base-pairs involve the RNA transcript bound to the DNA template strand.[17] As transcription progresses, ribonucleotides are added to the 3′ end of the RNA transcript and the RNAP complex moves along the DNA. The characteristic elongation rates in prokaryotes and eukaryotes are about 10–100 nts/sec.[18]

Aspartyl (asp) residues in the RNAP will hold on to Mg2+ ions, which will, in turn, coordinate the phosphates of the ribonucleotides. The first Mg2+ will hold on to the α-phosphate of the NTP to be added. This allows the nucleophilic attack of the 3′-OH from the RNA transcript, adding another NTP to the chain. The second Mg2+ will hold on to the pyrophosphate of the NTP.[19] The overall reaction equation is:

- (NMP)n + NTP → (NMP)n+1 + PPi

Fidelity

[edit]Unlike the proofreading mechanisms of DNA polymerase those of RNAP have only recently been investigated. Proofreading begins with separation of the mis-incorporated nucleotide from the DNA template. This pauses transcription. The polymerase then backtracks by one position and cleaves the dinucleotide that contains the mismatched nucleotide. In the RNA polymerase this occurs at the same active site used for polymerization and is therefore markedly different from the DNA polymerase where proofreading occurs at a distinct nuclease active site.[20]

The overall error rate is around 10−4 to 10−6.[21]

Termination

[edit]In bacteria, termination of RNA transcription can be rho-dependent or rho-independent. The former relies on the rho factor, which destabilizes the DNA-RNA heteroduplex and causes RNA release.[22] The latter, also known as intrinsic termination, relies on a palindromic region of DNA. Transcribing the region causes the formation of a "hairpin" structure from the RNA transcription looping and binding upon itself. This hairpin structure is often rich in G-C base-pairs, making it more stable than the DNA-RNA hybrid itself. As a result, the 8 bp DNA-RNA hybrid in the transcription complex shifts to a 4 bp hybrid. These last 4 base pairs are weak A-U base pairs, and the entire RNA transcript will fall off the DNA.[23]

Transcription termination in eukaryotes is less well understood than in bacteria, but involves cleavage of the new transcript followed by template-independent addition of adenines at its new 3′ end, in a process called polyadenylation.[24]

Other organisms

[edit]Given that DNA and RNA polymerases both carry out template-dependent nucleotide polymerization, it might be expected that the two types of enzymes would be structurally related. However, x-ray crystallographic studies of both types of enzymes reveal that, other than containing a critical Mg2+ ion at the catalytic site, they are virtually unrelated to each other; indeed template-dependent nucleotide polymerizing enzymes seem to have arisen independently twice during the early evolution of cells. One lineage led to the modern DNA polymerases and reverse transcriptases, as well as to a few single-subunit RNA polymerases (ssRNAP) from phages and organelles.[2] The other multi-subunit RNAP lineage formed all of the modern cellular RNA polymerases.[25][1]

Bacteria

[edit]In bacteria, the same enzyme catalyzes the synthesis of mRNA and non-coding RNA (ncRNA).

RNAP is a large molecule. The core enzyme has five subunits (~ 400 kDa):[26]

- β′

- The β′ subunit is the largest subunit, and is encoded by the rpoC gene.[27] The β′ subunit contains part of the active center responsible for RNA synthesis and contains some of the determinants for non-sequence-specific interactions with DNA and nascent RNA. It is split into two subunits in Cyanobacteria and chloroplasts.[28]

- β

- The β subunit is the second-largest subunit, and is encoded by the rpoB gene. The β subunit contains the rest of the active center responsible for RNA synthesis and contains the rest of the determinants for non-sequence-specific interactions with DNA and nascent RNA.

- α (αI and αII)

- Two copies of the α subunit, being the third-largest subunit, are present in a molecule of RNAP: αI and αII (one and two). Each α subunit contains two domains: αNTD (N-terminal domain) and αCTD (C-terminal domain). αNTD contains determinants for assembly of RNAP. αCTD (C-terminal domain) contains determinants for interaction with promoter DNA, making non-sequence-non-specific interactions at most promoters and sequence-specific interactions at upstream-element-containing promoters, and contains determinants for interactions with regulatory factors.

- ω

- The ω subunit is the smallest subunit. The ω subunit facilitates assembly of RNAP and stabilizes assembled RNAP.[29]

In order to bind promoters, RNAP core associates with the transcription initiation factor sigma (σ) to form RNA polymerase holoenzyme. Sigma reduces the affinity of RNAP for nonspecific DNA while increasing specificity for promoters, allowing transcription to initiate at correct sites. The complete holoenzyme therefore has 6 subunits: β′βαI and αIIωσ (~450 kDa).

Eukaryotes

[edit]

Eukaryotes have multiple types of nuclear RNAP, each responsible for synthesis of a distinct subset of RNA. All are structurally and mechanistically related to each other and to bacterial RNAP:

- RNA polymerase I synthesizes a pre-rRNA 45S (35S in yeast), which matures into 28S, 18S and 5.8S rRNAs, which will form the major RNA sections of the ribosome.[30]

- RNA polymerase II synthesizes precursors of mRNAs and most snRNA and microRNAs.[31] This is the most studied type, and, due to the high level of control required over transcription, a range of transcription factors are required for its binding to promoters.

- RNA polymerase III synthesizes tRNAs, rRNA 5S and other small RNAs found in the nucleus and cytosol.[32]

- RNA polymerase IV synthesizes siRNA in plants.[33]

- RNA polymerase V synthesizes RNAs involved in siRNA-directed heterochromatin formation in plants.[34]

Eukaryotic chloroplasts contain a multi-subunit RNAP ("PEP, plastid-encoded polymerase"). Due to its bacterial origin, the organization of PEP resembles that of current bacterial RNA polymerases: It is encoded by the RPOA, RPOB, RPOC1 and RPOC2 genes on the plastome, which as proteins form the core subunits of PEP, respectively named α, β, β′ and β″.[35] Similar to the RNA polymerase in E. coli, PEP requires the presence of sigma (σ) factors for the recognition of its promoters, containing the -10 and -35 motifs.[36] Despite the many commonalities between plant organellar and bacterial RNA polymerases and their structure, PEP additionally requires the association of a number of nuclear encoded proteins, termed PAPs (PEP-associated proteins), which form essential components that are closely associated with the PEP complex in plants. Initially, a group consisting of 10 PAPs was identified through biochemical methods, which was later extended to 12 PAPs.[37][38]

Chloroplast also contain a second, structurally and mechanistically unrelated, single-subunit RNAP ("nucleus-encoded polymerase, NEP"). Eukaryotic mitochondria use POLRMT (human), a nucleus-encoded single-subunit RNAP.[2] Such phage-like polymerases are referred to as RpoT in plants.[39]

Archaea

[edit]Archaea have a single type of RNAP, responsible for the synthesis of all RNA. Archaeal RNAP is structurally and mechanistically similar to bacterial RNAP and eukaryotic nuclear RNAP I-V, and is especially closely structurally and mechanistically related to eukaryotic nuclear RNAP II.[8][40] The history of the discovery of the archaeal RNA polymerase is quite recent. The first analysis of the RNAP of an archaeon was performed in 1971, when the RNAP from the extreme halophile Halobacterium cutirubrum was isolated and purified.[41] Crystal structures of RNAPs from Sulfolobus solfataricus and Sulfolobus shibatae set the total number of identified archaeal subunits at thirteen.[8][42]

Archaea has the subunit corresponding to Eukaryotic Rpb1 split into two. There is no homolog to eukaryotic Rpb9 (POLR2I) in the S. shibatae complex, although TFS (TFIIS homolog) has been proposed as one based on similarity. There is an additional subunit dubbed Rpo13; together with Rpo5 it occupies a space filled by an insertion found in bacterial β′ subunits (1,377–1,420 in Taq).[8] An earlier, lower-resolution study on S. solfataricus structure did not find Rpo13 and only assigned the space to Rpo5/Rpb5. Rpo3 is notable in that it's an iron–sulfur protein. RNAP I/III subunit AC40 found in some eukaryotes share similar sequences,[42] but does not bind iron.[43] This domain, in either case, serves a structural function.[44]

Archaeal RNAP subunit previously used an "RpoX" nomenclature where each subunit is assigned a letter in a way unrelated to any other systems.[1] In 2009, a new nomenclature based on Eukaryotic Pol II subunit "Rpb" numbering was proposed.[8]

Viruses

[edit]

Orthopoxviruses and some other nucleocytoplasmic large DNA viruses synthesize RNA using a virally encoded multi-subunit RNAP. They are most similar to eukaryotic RNAPs, with some subunits minified or removed.[45] Exactly which RNAP they are most similar to is a topic of debate.[46] Most other viruses that synthesize RNA use unrelated mechanics.

Many viruses use a single-subunit DNA-dependent RNAP (ssRNAP) that is structurally and mechanistically related to the single-subunit RNAP of eukaryotic chloroplasts (RpoT) and mitochondria (POLRMT) and, more distantly, to DNA polymerases and reverse transcriptases. Perhaps the most widely studied such single-subunit RNAP is bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase. ssRNAPs cannot proofread.[2]

B. subtilis prophage SPβ uses YonO, a homolog of the β+β′ subunits of msRNAPs to form a monomeric (both barrels on the same chain) RNAP distinct from the usual "right hand" ssRNAP. It probably diverged very long ago from the canonical five-unit msRNAP, before the time of the last universal common ancestor.[47][48]

Other viruses use an RNA-dependent RNAP (an RNAP that employs RNA as a template instead of DNA). This occurs in negative strand RNA viruses and dsRNA viruses, both of which exist for a portion of their life cycle as double-stranded RNA. However, some positive strand RNA viruses, such as poliovirus, also contain RNA-dependent RNAP.[49]

History

[edit]RNAP was discovered independently by Sam Weiss, Audrey Stevens, and Jerard Hurwitz in 1960.[50] By this time, one half of the 1959 Nobel Prize in Medicine had been awarded to Severo Ochoa for the discovery of what was believed to be RNAP,[51] but instead turned out to be polynucleotide phosphorylase.

Purification

[edit]RNA polymerase can be isolated in the following ways:

- By a phosphocellulose column.[52]

- By glycerol gradient centrifugation.[53]

- By a DNA column.

- By an ion chromatography column.[54]

And also combinations of the above techniques.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Werner F, Grohmann D (February 2011). "Evolution of multisubunit RNA polymerases in the three domains of life". Nature Reviews. Microbiology. 9 (2): 85–98. doi:10.1038/nrmicro2507. PMID 21233849. S2CID 30004345. See also Cramer 2002: Cramer P (February 2002). "Multisubunit RNA polymerases". Current Opinion in Structural Biology. 12 (1): 89–97. doi:10.1016/s0959-440x(02)00294-4. PMID 11839495.

- ^ a b c d Cermakian N, Ikeda TM, Miramontes P, Lang BF, Gray MW, Cedergren R (December 1997). "On the evolution of the single-subunit RNA polymerases". Journal of Molecular Evolution. 45 (6): 671–681. Bibcode:1997JMolE..45..671C. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.520.3555. doi:10.1007/PL00006271. PMID 9419244. S2CID 1624391.

- ^ Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2006

- ^ Stoddart C (1 March 2022). "Structural biology: How proteins got their close-up". Knowable Magazine. doi:10.1146/knowable-022822-1. Retrieved 25 March 2022.

- ^ Griffiths AJF, Miller JH, Suzuki DT, et al. An Introduction to Genetic Analysis. 7th edition. New York: W. H. Freeman; 2000. Chapter 10.

- ^ Finn RD, Orlova EV, Gowen B, Buck M, van Heel M (December 2000). "Escherichia coli RNA polymerase core and holoenzyme structures". The EMBO Journal. 19 (24): 6833–6844. doi:10.1093/emboj/19.24.6833. PMC 305883. PMID 11118218.

- ^ Zhang G, Campbell EA, Minakhin L, Richter C, Severinov K, Darst SA (September 1999). "Crystal structure of Thermus aquaticus core RNA polymerase at 3.3 A resolution". Cell. 98 (6): 811–824. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81515-9. PMID 10499798.

- ^ a b c d e Korkhin Y, Unligil UM, Littlefield O, Nelson PJ, Stuart DI, Sigler PB, et al. (May 2009). "Evolution of complex RNA polymerases: the complete archaeal RNA polymerase structure". PLOS Biology. 7 (5) e1000102. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1000102. PMC 2675907. PMID 19419240.

- ^ Alberts B (2014-11-18). Molecular Biology of the Cell (Sixth ed.). New York, NY: Garland Science, Taylor and Francis Group. ISBN 9780815344322. OCLC 887605755.

- ^ Markov D, Naryshkina T, Mustaev A, Severinov K (September 1999). "A zinc-binding site in the largest subunit of DNA-dependent RNA polymerase is involved in enzyme assembly". Genes & Development. 13 (18): 2439–2448. doi:10.1101/gad.13.18.2439. PMC 317019. PMID 10500100.

- ^ Ishihama A (2000). "Functional modulation of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase". Annual Review of Microbiology. 54: 499–518. doi:10.1146/annurev.micro.54.1.499. PMID 11018136.

- ^ InterPro: IPR011260

- ^ Roeder RG (November 1991). "The complexities of eukaryotic transcription initiation: regulation of preinitiation complex assembly". Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 16 (11): 402–408. doi:10.1016/0968-0004(91)90164-Q. PMID 1776168.

- ^ a b Watson JD, Baker TA, Bell SP, Gann AA, Levine M, Losick RM (2013). Molecular Biology of the Gene (7th ed.). Pearson.

- ^ Revyakin A, Liu C, Ebright RH, Strick TR (November 2006). "Abortive initiation and productive initiation by RNA polymerase involve DNA scrunching". Science. 314 (5802): 1139–1143. Bibcode:2006Sci...314.1139R. doi:10.1126/science.1131398. PMC 2754787. PMID 17110577.

- ^ Goldman SR, Ebright RH, Nickels BE (May 2009). "Direct detection of abortive RNA transcripts in vivo". Science. 324 (5929): 927–928. Bibcode:2009Sci...324..927G. doi:10.1126/science.1169237. PMC 2718712. PMID 19443781.

- ^ Kettenberger H, Armache KJ, Cramer P (December 2004). "Complete RNA polymerase II elongation complex structure and its interactions with NTP and TFIIS". Molecular Cell. 16 (6): 955–965. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2004.11.040. hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-0015-84E1-D. PMID 15610738.

- ^ Milo R, Philips R. "Cell Biology by the Numbers: What is faster, transcription or translation?". book.bionumbers.org. Archived from the original on 20 April 2017. Retrieved 8 March 2017.

- ^ Svetlov V, Nudler E (January 2013). "Basic mechanism of transcription by RNA polymerase II". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Gene Regulatory Mechanisms. 1829 (1): 20–28. doi:10.1016/j.bbagrm.2012.08.009. PMC 3545073. PMID 22982365.

- ^ Sydow JF, Cramer P (December 2009). "RNA polymerase fidelity and transcriptional proofreading". Current Opinion in Structural Biology. 19 (6): 732–739. doi:10.1016/j.sbi.2009.10.009. hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-0015-837E-8. PMID 19914059.

- ^ Philips R, Milo R. "What is the error rate in transcription and translation?". Retrieved 26 March 2019.

- ^ Richardson JP (September 2002). "Rho-dependent termination and ATPases in transcript termination". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Gene Structure and Expression. 1577 (2): 251–260. doi:10.1016/S0167-4781(02)00456-6. PMID 12213656.

- ^ Porrua O, Boudvillain M, Libri D (August 2016). "Transcription Termination: Variations on Common Themes". Trends in Genetics. 32 (8): 508–522. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2016.05.007. PMID 27371117.

- ^ Lykke-Andersen S, Jensen TH (October 2007). "Overlapping pathways dictate termination of RNA polymerase II transcription". Biochimie. 89 (10): 1177–1182. doi:10.1016/j.biochi.2007.05.007. PMID 17629387.

- ^ Stiller JW, Duffield EC, Hall BD (September 1998). "Amitochondriate amoebae and the evolution of DNA-dependent RNA polymerase II". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 95 (20): 11769–11774. Bibcode:1998PNAS...9511769S. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.20.11769. PMC 21715. PMID 9751740.

- ^ Ebright RH (December 2000). "RNA polymerase: structural similarities between bacterial RNA polymerase and eukaryotic RNA polymerase II". Journal of Molecular Biology. 304 (5): 687–698. doi:10.1006/jmbi.2000.4309. PMID 11124018.

- ^ Monastyrskaya GS, Gubanov VV, Guryev SO, Salomatina IS, Shuvaeva TM, Lipkin VM, et al. (July 1982). "The primary structure of E. coli RNA polymerase, Nucleotide sequence of the rpoC gene and amino acid sequence of the beta′-subunit". Nucleic Acids Research. 10 (13): 4035–4044. doi:10.1093/nar/10.13.4035. PMC 320776. PMID 6287430.

- ^ Bergsland KJ, Haselkorn R (June 1991). "Evolutionary relationships among eubacteria, cyanobacteria, and chloroplasts: Evidence from the rpoC1 gene of Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120". Journal of Bacteriology. 173 (11): 3446–3455. doi:10.1128/jb.173.11.3446-3455.1991. PMC 207958. PMID 1904436.

- ^ Mathew R, Chatterji D (October 2006). "The evolving story of the omega subunit of bacterial RNA polymerase". Trends in Microbiology. 14 (10): 450–455. doi:10.1016/j.tim.2006.08.002. PMID 16908155.

- ^ Grummt I (1999). Regulation of mammalian ribosomal gene transcription by RNA polymerase I. Progress in Nucleic Acid Research and Molecular Biology. Vol. 62. pp. 109–54. doi:10.1016/S0079-6603(08)60506-1. ISBN 9780125400626. PMID 9932453.

- ^ Lee Y, Kim M, Han J, Yeom KH, Lee S, Baek SH, et al. (October 2004). "MicroRNA genes are transcribed by RNA polymerase II". The EMBO Journal. 23 (20): 4051–4060. doi:10.1038/sj.emboj.7600385. PMC 524334. PMID 15372072.

- ^ Willis IM (February 1993). "RNA polymerase III. Genes, factors and transcriptional specificity". European Journal of Biochemistry. 212 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb17626.x. PMID 8444147.

- ^ Herr AJ, Jensen MB, Dalmay T, Baulcombe DC (April 2005). "RNA polymerase IV directs silencing of endogenous DNA". Science. 308 (5718): 118–120. Bibcode:2005Sci...308..118H. doi:10.1126/science.1106910. PMID 15692015. S2CID 206507767.

- ^ Wierzbicki AT, Ream TS, Haag JR, Pikaard CS (May 2009). "RNA polymerase V transcription guides ARGONAUTE4 to chromatin". Nature Genetics. 41 (5): 630–634. doi:10.1038/ng.365. PMC 2674513. PMID 19377477.

- ^ Pfannschmidt T, Ogrzewalla K, Baginsky S, Sickmann A, Meyer HE, Link G (January 2000). "The multisubunit chloroplast RNA polymerase A from mustard (Sinapis alba L.). Integration of a prokaryotic core into a larger complex with organelle-specific functions". European Journal of Biochemistry. 267 (1): 253–261. doi:10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.00991.x. PMID 10601874.

- ^ Chi W, He B, Mao J, Jiang J, Zhang L (September 2015). "Plastid sigma factors: Their individual functions and regulation in transcription". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Bioenergetics. SI: Chloroplast Biogenesis. 1847 (9): 770–778. doi:10.1016/j.bbabio.2015.01.001. PMID 25596450.

- ^ Pfalz J, Pfannschmidt T (April 2013). "Essential nucleoid proteins in early chloroplast development". Trends in Plant Science. 18 (4): 186–94. Bibcode:2013TPS....18..186P. doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2012.11.003. PMID 23246438.

- ^ Steiner S, Schröter Y, Pfalz J, Pfannschmidt T (November 2011). "Identification of essential subunits in the plastid-encoded RNA polymerase complex reveals building blocks for proper plastid development". Plant Physiology. 157 (3): 1043–1055. doi:10.1104/pp.111.184515. PMC 3252157. PMID 21949211.

- ^ Schweer J, Türkeri H, Kolpack A, Link G (December 2010). "Role and regulation of plastid sigma factors and their functional interactors during chloroplast transcription - recent lessons from Arabidopsis thaliana". European Journal of Cell Biology. 89 (12): 940–946. doi:10.1016/j.ejcb.2010.06.016. PMID 20701995.

- ^ Werner F (September 2007). "Structure and function of archaeal RNA polymerases". Molecular Microbiology. 65 (6): 1395–1404. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05876.x. PMID 17697097.

- ^ Louis BG, Fitt PS (February 1971). "Nucleic acid enzymology of extremely halophilic bacteria. Halobacterium cutirubrum deoxyribonucleic acid-dependent ribonucleic acid polymerase". The Biochemical Journal. 121 (4): 621–627. doi:10.1042/bj1210621. PMC 1176638. PMID 4940048.

- ^ a b Hirata A, Klein BJ, Murakami KS (February 2008). "The X-ray crystal structure of RNA polymerase from Archaea". Nature. 451 (7180): 851–854. Bibcode:2008Natur.451..851H. doi:10.1038/nature06530. PMC 2805805. PMID 18235446.

- ^ Fernández-Tornero C, Moreno-Morcillo M, Rashid UJ, Taylor NM, Ruiz FM, Gruene T, et al. (October 2013). "Crystal structure of the 14-subunit RNA polymerase I". Nature. 502 (7473): 644–649. Bibcode:2013Natur.502..644F. doi:10.1038/nature12636. PMID 24153184. S2CID 205235881.

- ^ Jennings ME, Lessner FH, Karr EA, Lessner DJ (February 2017). "The [4Fe-4S] clusters of Rpo3 are key determinants in the post Rpo3/Rpo11 heterodimer formation of RNA polymerase in Methanosarcina acetivorans". MicrobiologyOpen. 6 (1) e00399. Bibcode:2017MBioO...6..399J. doi:10.1002/mbo3.399. PMC 5300874. PMID 27557794.

- ^ Mirzakhanyan Y, Gershon PD (September 2017). "Multisubunit DNA-Dependent RNA Polymerases from Vaccinia Virus and Other Nucleocytoplasmic Large-DNA Viruses: Impressions from the Age of Structure". Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 81 (3) e00010-17. doi:10.1128/MMBR.00010-17. PMC 5584312. PMID 28701329.

- ^ Guglielmini J, Woo AC, Krupovic M, Forterre P, Gaia M (September 2019). "Diversification of giant and large eukaryotic dsDNA viruses predated the origin of modern eukaryotes". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 116 (39): 19585–19592. Bibcode:2019PNAS..11619585G. doi:10.1073/pnas.1912006116. PMC 6765235. PMID 31506349.

- ^ Forrest D, James K, Yuzenkova Y, Zenkin N (June 2017). "Single-peptide DNA-dependent RNA polymerase homologous to multi-subunit RNA polymerase". Nature Communications. 8 15774. Bibcode:2017NatCo...815774F. doi:10.1038/ncomms15774. PMC 5467207. PMID 28585540.

- ^ Sauguet L (September 2019). "The Extended "Two-Barrel" Polymerases Superfamily: Structure, Function and Evolution". Journal of Molecular Biology. 431 (20): 4167–4183. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2019.05.017. PMID 31103775.

- ^ Ahlquist P (May 2002). "RNA-dependent RNA polymerases, viruses, and RNA silencing". Science. 296 (5571): 1270–1273. Bibcode:2002Sci...296.1270A. doi:10.1126/science.1069132. PMID 12016304. S2CID 42526536.

- ^ Hurwitz J (December 2005). "The discovery of RNA polymerase". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 280 (52): 42477–42485. doi:10.1074/jbc.X500006200. PMID 16230341.

- ^ Nobel Prize 1959

- ^ Kelly JL, Lehman IR (August 1986). "Yeast mitochondrial RNA polymerase. Purification and properties of the catalytic subunit". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 261 (22): 10340–10347. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)67529-5. PMID 3525543.

- ^ Honda A, Mukaigawa J, Yokoiyama A, Kato A, Ueda S, Nagata K, et al. (April 1990). "Purification and molecular structure of RNA polymerase from influenza virus A/PR8". Journal of Biochemistry. 107 (4): 624–628. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a123097. PMID 2358436.

- ^ Hager DA, Jin DJ, Burgess RR (August 1990). "Use of Mono Q high-resolution ion-exchange chromatography to obtain highly pure and active Escherichia coli RNA polymerase". Biochemistry. 29 (34): 7890–7894. doi:10.1021/bi00486a016. PMID 2261443.

External links

[edit]- DNAi – DNA Interactive, including information and Flash clips on RNA Polymerase.

- RNA+Polymerase at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- EC 2.7.7.6

- RNA Polymerase – Synthesis RNA from DNA Template

(Wayback Machine copy)