Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Deshret

View on Wikipedia| Deshret | |

|---|---|

Deshret, the Red Crown of Lower Egypt | |

| Details | |

| Country | Ancient Egypt, Lower Egypt |

| ||||

| Deshret, Red Crown (crown as determinative) in hieroglyphs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Deshret (Ancient Egyptian: 𓂧𓈙𓂋𓏏𓋔, romanized: dšrt, lit. 'Red One') was the Red Crown of Lower Egypt. It was a red bowl shaped with a protruding curlicue. When combined with the Hedjet (White Crown) of Upper Egypt, it forms the Pschent (Double Crown), in ancient Egyptian called the sekhemti.

The Red Crown in Egyptian language hieroglyphs eventually was used as the vertical letter "n". The original "n" hieroglyph from the Predynastic Period and the Old Kingdom was the sign depicting ripples of water.

The word Deshret also referred to the desert Red Land on either side of Kemet (Black Land), the fertile Nile river basin.

Significance

[edit]In mythology, the earth deity Geb, original ruler of Egypt, invested Horus with the rule over Lower Egypt.[1] The Egyptian pharaohs, who saw themselves as successors of Horus, wore the deshret to symbolize their authority over Lower Egypt.[2] Other deities wore the deshret too, or were identified with it, such as the protective serpent goddess Wadjet and the creator-goddess of Sais, Neith, who often is shown wearing the Red Crown.[3]

The Red Crown would later be combined with the White Crown of Upper Egypt to form the Double Crown, symbolizing the rule over the whole country, "The Two Lands" as the Egyptians expressed it.[4]

Records

[edit]

No Red Crown has been found. Several ancient representations indicate it was woven like a basket from plant fiber such as grass, straw, flax, palm leaf, or reed.[citation needed]

The Red Crown frequently is mentioned in texts and depicted in reliefs and statues. An early example is the depiction of the victorious pharaoh wearing the deshret on the Narmer Palette. A label from the reign of Djer records a royal visit to the shrine of the Deshret which may have been located at Buto in the Nile delta.[8]

The fact that no crown has ever been found buried with any of the pharaohs, even in relatively intact tombs, might suggest that it was passed from one reign to the next, much as in present-day monarchies.

Toby Wilkinson has cited the iconography on rock art in the Eastern Desert region as depicting what he interpreted to be among the earliest representations of the royal crowns and suggested the Red Crown could have originated in the southern Nile Valley.[9]

Phonogram

[edit]

| ||

| 1 Red Crown, Deshret 2 also, vertical "N" in hieroglyphs | ||

|---|---|---|

Deshret, the ancient Egyptian Red Crown, is one of the oldest Egyptian hieroglyphs. As an iconographic element, it is used on the famous palette of Pharaoh Narmer as the "Red Crown of the Delta", the Delta being Lower Egypt.

The first usage of the Red Crown was in iconography as the symbol for Lower Egypt with the Nile Delta, horizontal letter 'n', Gardiner no. 35,

| |

Later it came to be used in the Egyptian language as an alphabetic uniliteral, vertical form for letter "n" as a phoneme or preposition. It became functional in running hieroglyphic texts, where either the horizontal or vertical form preposition satisfied space requirements.

Both the vertical and horizontal forms are prepositional equivalents, with the horizontal letter n, the N-water ripple (n hieroglyph) being more common, as well as more common to form parts of Egyptian language words requiring the phoneme 'n'.

One old use of the red crown hieroglyph is to make the word: 'in'!, (formerly an-(a-with dot)-(the "vertical feather" hieroglyph a, plus the red crown). Egyptian "in" is used at the beginning of a text and translates as: Behold!, or Lo!, and is an emphatic.

The Red Crown is also used as a determinative, most notably in the word for deshret. It is also used in other words or names of gods.

- Use in the Rosetta Stone

In the 198 BC Rosetta Stone, the 'Red Crown' as hieroglyph has the usage mostly of the vertical form of the preposition "n". In running text, word endings are not always at the end of hieroglyph blocks; when they are at the end, a simple transition to start the next block is a vertical separator, in this case the preposition, vertical n, (thus a space saver).

Since the start of the next hieroglyphic block could also be started with a horizontal "n" at the bottom of the previous block, it should be thought that the vertical "n" is also chosen for a visual effect; in other words, it visually spreads out the running text of words, instead of piling horizontal prepositions in a more tight text. Visually it is also a hieroglyph that takes up more 'space'-(versus a straight-line type for the horizontal water ripple); so it may have a dual purpose of a less compact text, and a better segue-transition to the next words.

The Red Crown hieroglyph is used 35 times in the Rosetta Stone; only 4 times is it used as a non-preposition. It averages once per line usage in the 36 line Decree of Memphis (Ptolemy V)-(Rosetta Stone).

See also

[edit]Gallery

[edit]-

modern drawing of a pharaoh with a red crown

-

Ramesside Period ostracon, pharaoh wearing Red Crown

-

Narmer Palette, front

-

Close-up of Narmer Palette, Pharaoh Narmer with crown

-

Bronze statuette of a Kushite king wearing the red crown of Lower Egypt; 25th Dynasty, c. 670 BCE, Neues Museum, Berlin

-

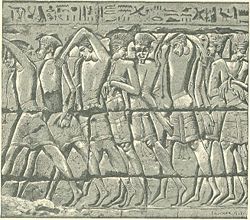

Philistine captives at Medinet Habu

-

Stele of Tchia at the Louvre

-

Apep being slain

References

[edit]- ^ Ewa Wasilewska, Creation Stories of the Middle East, Jessica Kingsley Publishers 2000, p.128

- ^ Toby A. H. Wilkinson, Early Dynastic Egypt, Routledge 1999, p.194

- ^ George Hart, The Routledge Dictionary Of Egyptian Gods And Goddesses, p.100

- ^ Ana Ruiz, The Spirit of Ancient Egypt, Algora Publishing 2001, p.8

- ^ Hollis, Susan Tower (3 October 2019). Five Egyptian Goddesses: Their Possible Beginnings, Actions, and Relationships in the Third Millennium BCE. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 29. ISBN 978-1-78093-794-6.

- ^ Chaos en beheersing: Documenten uit aeneolitisch Egypte. BRILL. 14 October 2024. p. 305. ISBN 978-90-04-67093-8.

Fragment of a "blacktopped" pot, red polished pottery with black rim, a representation of the "Red Crown" of Lower Egypt was modelled in the clay, before it was baked. Amratian (S.D. 35-39), from Naqada, tomb 1610. Oxford Ashmolean Museum 1895.795

- ^ "Black top shard 1895.795". www.ashmolean.org. Ashmolean Museum.

- ^ Toby A. H. Wilkinson, Early Dynastic Egypt, Routledge 1999, p.284

- ^ Wilkinson, Toby (2003). Genesis of the Pharaohs : dramatic new discoveries rewrite the origins of ancient Egypt. London: Thames & Hudson. pp. 54–82. ISBN 0500051224.

- ^ "Guardian Figure". www.metmuseum.org. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 9 February 2022.

- Budge. An Egyptian Hieroglyphic Dictionary, E.A.Wallace Budge, (Dover Publications), c 1978, (c 1920), Dover edition, 1978. (In two volumes) (softcover, ISBN 0-486-23615-3)

- Budge. The Rosetta Stone, E.A.Wallace Budge, (Dover Publications), c 1929, Dover edition(unabridged), 1989. (softcover, ISBN 0-486-26163-8)

Deshret

View on GrokipediaEtymology and Core Symbolism

Linguistic Origins

The term deshret (transliterated as dšrt in Egyptological convention) originates from the ancient Egyptian triliteral root dšr, which denotes the color red, as in the hue of blood, fire, or inflamed skin. This root appears in Old Egyptian texts from as early as the Pyramid Texts (c. 2400–2300 BCE), where dšr describes reddish phenomena, including divine fury manifesting as redness in faces or eyes. The addition of the feminine nisba ending -t yields dšrt, literally "the red (one)," grammatically classifying the crown as a feminine object in Egyptian nominal morphology. This etymology aligns with the crown's material and symbolic representation, often depicted using red ochre pigments in tomb paintings and artifacts dating to the Predynastic Period (c. 6000–3100 BCE), emphasizing its chromatic identity over functional or geographic descriptors alone. Standard Egyptological dictionaries, including those compiling Middle Egyptian lexicon (c. 2000 BCE), consistently derive dšrt from dšr without alternative primary roots, refuting claims of origins in terms like "barren" or "empty" as unsubstantiated by comparative Afro-Asiatic linguistics.[6] The term's application extended beyond the crown to the desert (dšrt, "red land"), highlighting a semantic field linking redness to arid, uncultivated expanses flanking the Nile, though the crown's designation predates explicit geographic dualism in written records.[7]Associations with Geography and Deities

The deshret crown symbolized Lower Egypt, the northern region encompassing the Nile Delta, the Mediterranean coastal areas, and adjacent western desert margins, areas renowned for their fertile alluvial soils enriched by annual Nile floods. This geographical association contrasted with Upper Egypt's white crown (hedjet), representing the southern river valley and highlands; the red color of deshret likely evoked the Delta's reddish clay deposits or the encircling red desert sands, though it also denoted the region's productivity, as the term deshret extended to the honeybee emblem of Lower Egyptian fertility.[4][1] Mythologically, the earth god Geb granted the deshret to Horus to affirm his sovereignty over Lower Egypt, positioning the falcon-headed deity as the archetypal ruler of the Delta in opposition to Set's claims on the region. The crown was prominently worn by Wadjet, the cobra goddess and tutelary deity of Lower Egypt, particularly linked to the city of Buto (Pe-Dep); as protector of the pharaoh and the northern land, she manifested as the rearing uraeus cobra affixed to the deshret, embodying royal authority and warding off threats.[1][1] Neith, the primordial creator and war goddess centered in Sais within the Delta, was also depicted donning the deshret, reinforcing her ties to northern Egyptian cosmology as a weaver of fate and hunter who bridged earthly and divine realms. These divine associations underscored the deshret's role in sacralizing Lower Egypt's landscape, where deities like Wadjet and Neith localized cosmic order amid the Delta's waterways and marshes.[8]Historical Origins and Evolution

Predynastic Development

The earliest archaeological evidence for the Deshret crown emerges in the late Naqada I phase of the Predynastic Period, approximately 3500 BCE, through incised or relief representations on pottery fragments. These depictions, found primarily in Upper Egyptian contexts such as near Nubt (modern Naqada), portray a bowl-shaped form with a characteristic spiraling extension at the rear, symbolizing emerging elite authority amid the cultural transitions of the Naqada culture. A specific sherd from a large vessel near Nubt, associated with the cult center of the god Set, features such a relief, indicating the crown's possible ties to regional deities and red symbolism linked to desert landscapes or chaos forces.[1] By the Naqada II period (c. 3500–3200 BCE), representations proliferated, reflecting political consolidation in proto-urban centers like Hierakonpolis and Naqada, though direct Lower Egyptian (Nile Delta) artifacts remain scarce due to poor preservation in alluvial soils. No physical crowns from this era have been recovered, suggesting use of perishable materials like leather or basketry for actual headgear, with ceramic motifs serving ceremonial or propagandistic purposes. The red hue consistently evoked deshret (red land), the arid deserts flanking the Nile, distinguishing it from fertile black soils and foreshadowing its role as a marker of northern territorial power.[9] Hypotheses on origins include derivation from animal motifs, such as an elephant trunk protuberance observed in some Naqada pottery, potentially linking to trade routes via Elephantine Island and early interactions between Upper and Lower Egypt. However, empirical evidence prioritizes its function as a status emblem in chieftain-level societies, evidenced by contextual finds alongside prestige goods like ivory combs and palettes, rather than uniform royal regalia. This evolution paralleled increasing social stratification, with the crown's form stabilizing by Naqada III (c. 3200–3000 BCE), setting the stage for its adoption by unifying rulers.[10]Early Dynastic Adoption and Usage

The Early Dynastic Period (c. 3100–2686 BCE), encompassing Dynasties 1 and 2, marked the formal integration of the Deshret crown into the regalia of unified Egyptian kingship, symbolizing sovereignty over Lower Egypt's Nile Delta region. This adoption followed the consolidation of power by early rulers such as Narmer, who is depicted wearing the Deshret in key artifacts, representing the extension of authority from Upper Egyptian centers like Hierakonpolis southward conquests northward./07:Ancient_Egypt/7.02:Pre-Dynastic_and_Early_Dynastic_Periods)[11] The Narmer Palette, a siltstone artifact dated to approximately 3100 BCE and excavated from the Main Deposit at Hierakonpolis, illustrates this usage prominently: on its reverse side, Narmer appears in procession barefoot and wearing the Deshret, accompanied by standards and attendants, while subjugating bound captives, thereby iconographically asserting dominance over Lower Egyptian territories. Similar depictions appear in Dynasty 1 inscriptions, such as ivory labels from Abydos tombs attributing military campaigns to kings like Aha, where the crown denotes regional control amid unification efforts.[12] In administrative and funerary contexts, the Deshret served to differentiate the king's dual rule, often contrasted with the Hedjet (White Crown) of Upper Egypt, though its standalone use emphasized Delta-specific legitimacy in early state formation.[13] This symbolic employment persisted through the period, as evidenced by cylinder seals and serekh emblems linking pharaonic identity to Lower Egyptian domains.[14]Iconography and Material Representations

Physical Characteristics

The Deshret crown is depicted in ancient Egyptian art as a tall, cylindrical or slightly bulbous headdress, tapering or flat at the top, with a prominent forward-projecting spiral or curlicue element at the brow and a rearward loop or spike-like extension.[1][3] This form is consistently rendered in red pigment to symbolize Lower Egypt, distinguishing it from the white Hedjet crown of Upper Egypt, and is often shown fitted closely over the pharaoh's brow, sometimes adorned with a rearing cobra (uraeus) representing the goddess Wadjet.[2][1] No physical examples of the Deshret crown have survived, likely due to its construction from perishable materials such as woven plant fibers—including grass, flax, straw, palm leaves, or reeds—or leather, possibly reinforced with a metal wire frame, such as copper, to maintain the spiral and loop shapes.[1][2][3] These hypotheses derive from the crown's fragile, non-metallic appearance in two-dimensional reliefs and paintings, as well as comparisons to surviving textile and fiber artifacts from the period.[1] In iconographic representations, the crown's proportions emphasize height and narrowness, evoking a stylized papyrus umbel or regional flora of the Nile Delta, with the frontal curl possibly imitating a bound coil of fibers or a symbolic plant stalk.[3] Variations in artistic depictions, such as slight elongations of the rear loop in Predynastic and Early Dynastic artifacts like the Narmer Palette (c. 3100 BCE), reflect consistency in core form across media, from palette carvings to temple reliefs and statues.[1][3] The hieroglyphic sign for Deshret (Gardiner D21) standardizes this shape as a standalone emblem, reinforcing its physical archetype in inscriptions and amulets from as early as the Naqada I period (c. 4000–3500 BCE).[3]Key Archaeological Artifacts

No physical examples of the Deshret crown itself have been archaeologically recovered, with representations limited to carvings, statues, and reliefs that illustrate its form and symbolic role.[15] These artifacts, spanning multiple dynasties, depict the crown as a tall, bowl-shaped red headdress with a rearward projection and frontal curl, often worn by pharaohs asserting dominion over Lower Egypt. The Narmer Palette, a ceremonial siltstone artifact unearthed in 1898 at Hierakonpolis (modern Nekhen) and dated to c. 3100 BCE, features the earliest known detailed depiction of the Deshret. On the reverse side, Pharaoh Narmer appears wearing the red crown, holding a mace and inspecting decapitated enemies, an iconographic motif signifying military victory and integration of Lower Egyptian territories. Standing 64 cm tall and carved in low bas-relief, the palette is preserved in the Egyptian Museum, Cairo, and its dual-sided imagery—contrasting the Deshret with the Hedjet white crown—evidences early pharaonic efforts toward national unification.[16][17] From the Middle Kingdom, a guardian statue dated to the 12th Dynasty (c. 1919–1885 BCE) portrays a figure in the Deshret crown, with facial traits mirroring those of Amenemhat II or Senusret II. Constructed of cedar wood overlaid with plaster and pigment, the 28.5 cm tall figure functioned as a protective sentinel for the imiut funerary emblem, highlighting the crown's ritual protective connotations beyond royal wear. Acquired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, this artifact exemplifies the Deshret's use in non-pharaonic divine guardianship during periods of centralized rule.[18] A bronze statuette of a Kushite ruler from the 25th Dynasty (c. 670 BCE), kneeling and adorned with the Deshret while presenting offerings, illustrates the crown's persistence under Nubian 25th Dynasty kings who emulated Egyptian regalia to legitimize control over the north. Measuring approximately 7.6 cm in height, such small-scale bronzes, often found in temple contexts like Saqqara, underscore the Deshret's role in affirming Lower Egyptian sovereignty even in foreign-led eras.[19]Role in Political and Religious Symbolism

Representation of Lower Egypt

The Deshret crown symbolized the pharaoh's sovereignty over Lower Egypt, the northern territory centered on the Nile Delta. This representation emphasized the ruler's authority in the fertile lowlands, contrasting with the Hedjet white crown of Upper Egypt. The association, while conventional by the Early Dynastic Period (c. 3100–2686 BCE), may trace origins to Upper Egyptian contexts, as evidenced by a Naqada I sherd (c. 4000–3500 BCE) from near Nubt depicting the crown.[1][2] In iconographic depictions, pharaohs wore the Deshret to assert control over Lower Egyptian domains, particularly in scenes of conquest and procession. On the verso of the Narmer Palette (c. 3100 BCE), Narmer appears with the red crown inspecting decapitated foes and bound captives, illustrating the subjugation and integration of northern regions following unification. Similarly, a label from Pharaoh Djer's reign (First Dynasty, c. 3000 BCE) records a visit to a Buto shrine, a key Lower Egyptian site, with the crown signifying regional dominion.[3][1] Symbolically, the Deshret embodied the protective and fertile aspects of Lower Egypt, linked to deities such as Wadjet, the cobra goddess embodying the Delta's guardianship, and Neith, associated with northern wisdom and warfare. Pharaohs like Ahmose I (c. 1550–1525 BCE) donned it in temple reliefs, such as those from his Abydos complex, to highlight renewed authority over the north after expelling the Hyksos. The crown's red hue evoked the encircling deserts (deshret land) framing the Delta's black soil, reinforcing geographic and cosmic rule.[2][1][3] Even non-native rulers adopted the Deshret to legitimize claims over Lower Egypt, as seen in 25th Dynasty Kushite iconography (c. 747–656 BCE), where kings wore it alongside other regalia to invoke traditional pharaonic legitimacy. This enduring symbolism persisted in amulets and guardian figures, underscoring the crown's role in rituals affirming unity under the Two Lands framework.[1]Integration in Unification Narratives

The Deshret crown's integration into ancient Egyptian unification narratives primarily manifests through its pairing with the Hedjet white crown to form the Pschent double crown, symbolizing the pharaoh's dominion over both Upper and Lower Egypt following political consolidation. This symbolism emerged prominently in the Early Dynastic Period, around 3100 BCE, as evidenced by the Narmer Palette, where Pharaoh Narmer appears wearing the Deshret on the reverse side during a procession, denoting his assertion of control over Lower Egyptian territories after subjugating Delta rulers depicted on the obverse under the white crown.[17][16] The palette's iconography, including bound captives and standards of conquered nomes, frames the Deshret as a trophy of unification achieved via military conquest originating from Upper Egypt, establishing a foundational mythos of national coherence under a single ruler.[17] Subsequent pharaohs invoked this narrative to legitimize reassertions of unity during periods of fragmentation. Mentuhotep II of the 11th Dynasty, reigning circa 2055–2004 BCE, adopted the double crown in statuary and reliefs after defeating Herakleopolitan rivals, thereby restoring centralized authority post-First Intermediate Period; his royal name change to Sematawy, meaning "Uniter of the Two Lands," explicitly tied Deshret's red symbolism to Lower Egypt's reintegration into the realm.[4][20] Reliefs from his Deir el-Bahri mortuary temple depict him with the Deshret alone or combined, reinforcing the crown's role in propagandistic depictions of territorial wholeness and divine kingship continuity.[21] In broader royal ideology, the Deshret's incorporation into unification motifs extended to temple inscriptions and victory stelae, where pharaohs like those of the New Kingdom referenced primordial conquests akin to Narmer's to justify expansions or suppressions of regional autonomy, portraying the red crown as an enduring emblem of Lower Egypt's subjugation and harmonious fusion with the southern domain.[3] This recurring motif, grounded in artifacts spanning millennia, underscores causal links between symbolic regalia and political hegemony rather than mere ceremonial adornment.Hieroglyphic and Linguistic Applications

Phonetic and Ideographic Functions

The hieroglyph depicting the Deshret, cataloged as Gardiner S3 (𓋔), primarily functioned ideographically to represent the Red Crown of Lower Egypt and related concepts such as the desert or "red land" (dšrt). As an ideogram, it directly conveyed the object's identity without phonetic transcription, appearing in royal titles, divine epithets, and geographical designations to symbolize Lower Egyptian sovereignty. This usage is attested across dynastic periods, from Early Dynastic palettes to Ptolemaic inscriptions, where the sign standalone evoked the crown's emblematic power.[22] In addition to its ideographic role, the S3 sign served phonetic functions as a uniliteral phonogram for the consonant /n/, particularly in horizontal form, and extended to vertical orientations in columnar texts. This phonetic value enabled its integration into diverse words unrelated to the crown, such as prepositions or nominal elements, enhancing the script's flexibility. For example, in the word dšrt itself, phonetic signs for d-š-r-t (often including D46 for d, S29 for š, D21 for r, and Z9 for t) precede the S3 determinative, which reinforces the ideographic meaning while the preceding signs provide pronunciation.[22][3] The dual phonetic-ideographic capacity of S3 exemplifies the Egyptian writing system's efficiency, where a single sign could shift between sound representation and conceptual denotation based on context. Scholarly analyses, drawing from corpus like the Rosetta Stone (196 BCE), confirm its determinative role in dšrt, distinguishing it from purely phonetic usages and underscoring its ties to royal iconography.[3]Examples in Inscriptions

The Deshret hieroglyph, designated as Gardiner sign S3, serves in ancient Egyptian inscriptions as an ideogram for the Red Crown and a determinative for terms denoting Lower Egypt, the desert (deshret, "red land"), or the crown itself. It frequently concludes the phonetic spelling of "dšrt" (deshret), comprising signs for /d/ (e.g., hand D46), /š/ (folded cloth S29), /r/ (mouth D21), and /t/ (bread T12 or loaf), with S3 providing the specific connotation of redness or the crown's form. This usage underscores its role in distinguishing the arid, red-soiled regions of Lower Egypt from the fertile black land (kmt) of Upper Egypt, appearing in geographical, administrative, and royal contexts from the Early Dynastic Period onward. Phonetically, S3 occasionally represents the uniliteral value /n/ or biliteral /jn/, particularly in Predynastic and Early Dynastic pot marks and labels where proto-hieroglyphic forms resemble the crown's shape for nominal elements. In fuller texts, such as Old Kingdom offering formulas and nome lists, it ideographically marks Lower Egyptian provinces (e.g., in the sequence of 22 Lower nomes enumerated in temple walls like those at Edfu, where S3 determinatives follow nomes like "Thinite" or "Busirite"). For instance, inscriptions on boundary stelae or annals, such as fragments of the Palermo Stone (c. 2392–2283 BCE), employ crown symbols alongside textual references to northern dominion, though S3 specifically denotes the red variant in contrast to the white Hedjet (S38).[23] In royal titulary, S3 features in epithets like "ḥqꜣ-dšrt" (ruler of the red [crown/land]), as seen in Middle Kingdom stelae and scarabs where pharaohs claim hegemony, such as Mentuhotep II's unification propaganda (c. 2055–2004 BCE), integrating the symbol with falcon or sedge motifs to signify control over both regions. Religious texts, including Coffin Texts (c. 2100–1800 BCE), invoke the Deshret in spells for the deceased king's assumption of divine regalia, with S3 determining "crown" in phrases granting eternal sovereignty. These applications highlight S3's versatility, evolving from Predynastic emblematic use to a standardized script element by the Fifth Dynasty (c. 2494–2345 BCE), verifiable through comparative analysis of corpus like the Thesaurus Linguae Aegyptiae.[24]Scholarly Debates and Modern Analysis

Theories on Origins

The earliest archaeological evidence for the Deshret crown dates to the late Naqada I period, approximately 3500 BCE, depicted in relief on a sherd from a large vessel excavated near Nubt (Ombos), a site in Upper Egypt associated with the god Set.[1] This predynastic artifact predates the more famous representations on the Narmer Palette (c. 3100 BCE), where the crown appears on pharaohs symbolizing conquest or rule over northern regions, and suggests the Deshret's form emerged in southern contexts before its firm association with Lower Egypt.[1] Scholars interpret this as evidence that the crown may have originated as a southern Egyptian symbol of authority, possibly ceremonial or linked to local elites, rather than exclusively tied to the Nile Delta from inception.[1] One theory posits a specific origin at Elephantine Island in southern Upper Egypt, where the crown's distinctive protruding curl resembles an upraised elephant trunk, evoking the region's historical ties to elephant ivory trade and its strategic position as a gateway between Upper Egypt and Nubia.[10] Proponents cite supporting predynastic rock drawings in the nearby Eastern Desert (Wadi Qash, fourth millennium BCE) and a black-topped potsherd from Naqada Tomb 1610 (excavated by Flinders Petrie in 1896), which feature similar crown-like forms potentially denoting early rulers' power derived from Elephantine's resources and symbolism.[10] This view challenges the traditional north-south dichotomy by arguing the Deshret was adopted by northern rulers through southern cultural diffusion or conquest narratives, with durable materials like ivory or red granite implying a prototypical, enduring artifact rather than ephemeral fabric versions.[10] Mythological accounts, preserved in later texts, attribute the Deshret's emergence to divine bestowal: the earth god Geb granting it to Horus to signify dominion over Lower Egypt, reflecting retrospective unification ideology rather than historical etiology.[1] However, the absence of surviving physical crowns—likely due to perishable materials like leather or fabric reinforced with copper—renders empirical origins speculative, with theories relying on iconographic continuity from predynastic southern sites.[1] Egyptologists emphasize that while the Deshret's red hue evoked the desert (dšrt, "red land"), its predynastic Upper Egyptian depictions indicate it functioned initially as a broader emblem of sovereignty before regional polarization during the Early Dynastic Period (c. 3100–2686 BCE).[1]Empirical Evidence vs. Ideological Interpretations

Archaeological evidence establishes the Deshret as a concrete symbol of Lower Egyptian authority from the Early Dynastic Period onward, with its earliest prominent depiction on the Narmer Palette, dated to circa 3100 BCE, showing the pharaoh wearing the red crown in a scene of triumph over bound captives, signifying conquest and integration of northern territories.[3] This artifact, alongside ostraca and statues from subsequent eras, such as Ramesside Period examples from the Metropolitan Museum (c. 1292–1075 BCE), consistently links the Deshret to the Nile Delta's rulership and protective deities like Wadjet, without requiring interpretive overlays.[1] Inscriptions and iconography across temples and tombs reinforce this through repeated motifs of pharaohs donning the crown to denote sovereignty over deshret, the "red land" encompassing desert fringes and fertile lowlands, grounded in observable material patterns rather than abstract theorizing.[4] Scholarly analysis of pre-dynastic pottery sherds from Naqada II sites (c. 3500–3200 BCE) indicates the Deshret's form may have emerged in Upper Egypt, potentially at locales like Elephantine, before its adoption as Lower Egypt's emblem, evidenced by stylistic consistencies in crown shapes on local artifacts.[10] This empirical finding, derived from stratigraphic dating and comparative typology, underscores cultural diffusion across the Nile Valley predating political unification, countering assumptions of isolated regional invention.[1] Such data-driven reconstructions prioritize artifactual distribution and morphological evolution over narrative-driven attributions. Ideological interpretations, however, have occasionally subordinated this evidence to external agendas, as seen in 19th-century Egyptology where colonial-era scholars, shaped by racial typologies, framed Deshret symbolism within Hamitic migration theories that downplayed Nile Valley autochthony in favor of external "civilizing" influences. More recently, Afrocentric perspectives have reinterpreted the crown's red hue and associations with desert motifs as markers of sub-Saharan African identity, invoking linguistic ties like "deshret" to blood or skin tones, despite osteological studies of predynastic remains revealing craniofacial traits aligned with North African variability rather than equatorial archetypes.[25] These views, often amplified in non-peer-reviewed advocacy, diverge from genetic analyses of ancient Egyptian samples (e.g., Abusir el-Meleq mummies, c. 1388 BCE–426 CE), which demonstrate continuity with Levantine and Anatolian gene pools over time, with limited sub-Saharan admixture until later periods. Mainstream Egyptology critiques such impositions for retrofitting symbolism to modern racial binaries, advocating instead for contextual analysis of crowns as politico-religious tools evidenced by their invariant use in unification iconography.[26] This empirical restraint avoids the confirmation biases evident in ideologically motivated scholarship, where source selection favors anecdotal or selective readings over comprehensive artifact corpora.References

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bronze_statuette_of_a_Kushite_king_wearing_the_crown_of_Lower_Egypt._25th_Dynasty%2C_670_BCE._Neues_Museum.jpg