Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

List of wind deities

View on Wikipedia

A wind god is a god who controls the wind(s). Air deities may also be considered here as wind is nothing more than moving air. Many polytheistic religions have one or more wind gods. They may also have a separate air god or a wind god may double as an air god. Many wind gods are also linked with one of the four seasons.

Africa/South Africa

[edit]Yoruba tradito the goddess of wind storms and transformation.

oya goddess of storms and string winds and lighting and air

Nomkhubulwana/Nomkhubulwane, an angel associated with rain.

yemaya is most powerful goddess she formed the oceans and rivers when her water broke while she was giving birth to her first child

greek goddess rand is greek god of south africa and known for his currency south africa money and coins and he a single man of south africa

zulu she is south africa goddess she dwells in water.

african goddess of money is aje is goddess of wealth and prosperity

anyanwu is the sun goddess

mawu is a prominent creator, ruling the moon and night sky

Egyptian

[edit]- Amun, god of creation and the wind.

- Henkhisesui, god of the east wind. In art, Henkhisesui appears as a winged man with a ram head, or a winged, ram headed Scarab.[1]

- Ḥutchai, god of the west wind.[2] In art, Hutchai appears as a winged man with a snake head.[citation needed]

- Qebui, god of the north wind[3] who appears as a man with four ram heads or a winged ram with four heads.[4][5]

- Shehbui, god of the south wind.[2] In art, Shehbui appears as a winged man with a lion head.

- Shu, god of the air. and wind

-

Henkhisesui

-

Ḥutchai

-

Qebui

-

Shehbui

-

Qebui alternative form

-

Henkhisesui alternative form

Pokot

[edit]- Yomöt, god of the wind.

Europe

[edit]Albanian

[edit]- Shurdhi, weather god who causes hailstorms and throws thunder and lightning.

- Verbti, weather god who causes hailstorms and controls the water and the northern wind.

Balto-Slavic

[edit]Lithuanian

[edit]- Vejopatis, god of the wind according to at least one tradition.

Slavic

[edit]- Dogoda is the goddess of the west wind, and of love and gentleness.

- Stribog is the name of the Slavic god of winds, sky and air. He is said to be the ancestor (grandfather) of the winds of the eight directions.

- Moryana is the personification of the cold and harsh wind blowing from the sea to the land, as well as the water spirit.

- Varpulis is the companion of the thunder god Perun who was known in Central Europe and Lithuania.

Basque

[edit]Celtic

[edit]- Sídhe or Aos Sí were the pantheon of pre-Christian Ireland. Sídhe is usually taken as "fairy folk", but it is also Old Irish for wind or gust.[7]

- Borrum, Celtic god of the winds.[citation needed]

Germanic

[edit]- Kári, son of Fornjót and brother to Ægir and Logi, god of wind, apparently as its personification, much like his brothers personify sea and fire.

- Njörð, god of the wind, especially as it concerns sailors.

- Odin, thought by some scholars to be a god of the air/breath.[citation needed]

Greco-Roman

[edit]- Aeolus, keeper of the winds; later writers made him a full-fledged god.

- Anemoi, (in Greek, Ἄνεμοι—"winds") were the Greek wind gods.

- Aura, the breeze personified.

- Aurai, nymphs of the breeze.

- Cardea, Roman goddess of health, thresholds, door hinges, and handles; associated with the wind.

- Tritopatores, gods of wind and marriage

- Thraskias (Θρασκίας), god of the north-northwest wind

- Venti, (Latin, "winds") deities equivalent to the Greek Anemoi.

Western Asia

[edit]Persian Zoroastarian

[edit]- Vayu-Vata, two gods often paired together; the former was the god of wind and the latter was the god of the atmosphere/air.

- Enlil, the Sumerian god of air, wind, breath, loft.

- Ninlil, goddess of the wind and consort of Enlil.

- Pazuzu, king of the wind demons, demon of the southwest wind, and son of the god Hanbi.

Uralic

[edit]Finnish

[edit]- Ilmarinen, blacksmith and god of the wind, weather and air.

- Tuuletar, goddess or spirit of the wind.

Hungarian

[edit]- Szélatya, the Hungarian god of wind. [citation needed]

- Szélanya, the Hungarian goddess of wind and daughter of the primordial god Kayra. [citation needed]

- Zada, keeper of the precious Yada Tashy stone. [citation needed]

Sami

[edit]- Bieggolmai, unpredictable shovel-wielding god of the summer winds.

- Biegkegaellies, god of the winter winds.

Asia-Pacific / Oceania

[edit]South and East Asia

[edit]India

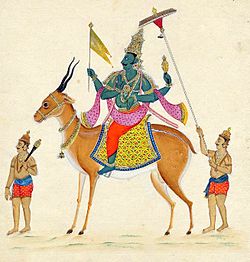

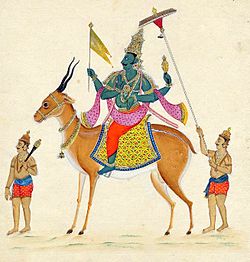

[edit]- Vayu, god of the winds and air.

- Rudra, Vedic god of storms, winds, and the hunt.

- Swasti, consort of Vayu and shakti or power that of Vayu.

Hindu-Vedic

[edit]- Maruts, attendants of Indra, sometimes the same as the below group of gods.

- Rudra, wind or storm god.

- Rudras, followers of Rudra.

- Vayu, god of wind.

Chinese

[edit]- Fei Lian, the Chinese wind god; Feng Bo is the human form of Fei Lian.

- Feng Po Po, the Chinese wind goddess.

- Feng Hao, general of the wind.

- Han Zixian, assistant goddess of the wind.

Japanese

[edit]- Fūjin, the wind god.

- Shinatsuhiko, god of the winds.

- Susanoo, the god of storms.

Korean

[edit]- Yondung Halmoni, goddess revered by farmers and sailors.

Vietnamese

[edit]- Thần Gió, the wind god.

Austronesia

[edit]Philippine

[edit]- Amihan, the Tagalog and Visayan goddess of the northeast winds. She is also known as Alunsina.

- Anitun Tabu, the fickle-minded ancient Tagalog goddess of wind and rain.

- Apo Angin, the Ilocano god of wind.

- Buhawi, the Tagalog god of whirlwinds and hurricanes' arcs. He is the enemy of Habagat.

- Habagat, the Tagalog god of winds and also referred to as the god of rain, and is often associated with the rainy season. He rules the kingdom of silver and gold in the sky, or the whole Himpapawirin (atmosphere).

- Lihangin, the Visayan god of the wind.

- Linamin at Barat, the goddess of monsoon winds in Palawan.

Polynesian

[edit]Hawaiian

[edit]- Hine-Tu-Whenua, Hawaiian goddess of wind and safe journeys.

- La'a Maomao, Hawaiian god of the wind and forgiveness.

- Pakaa, Hawaiian god of the wind and inventor of the sail.

Winds of Māui

[edit]The Polynesian trickster hero Māui captured or attempted to capture many winds during his travels.

- Fisaga, the gentle breeze, the only wind that Māui failed to capture

- Mata Upola, the east wind.

- Matuu, the north wind.

Māori

[edit]- Hanui-o-Rangi.

- Tāwhirimātea, Māori god of weather, including thunder and lightning, wind, clouds, and storms.

Native American

[edit]North America

[edit]Anishinaabe

[edit]- Epigishmog, god of the west wind and spiritual being of ultimate destiny.

Cherokee

[edit]- Oonawieh Unggi, the ancient spirit of the wind.

Iroquois

[edit]- Da-jo-jo, mighty panther spirit of the west wind.

- Gǎ-oh, spirit of the wind.

- Ne-o-gah, gentle fawn spirit of the south wind.

- O-yan-do-ne, moose spirit of the east wind.

- Ya-o-gah, destructive bear spirit of the north wind who is stopped by Gǎ-oh.

Inuit

[edit]- Silap Inua, the weather god who represents the breath of life and lures children to be lost in the tundra.

Lakota

[edit]- Okaga, fertility goddess of the south winds.

- Taku Skanskan, capricious master of the four winds.

- Tate, a wind god or spirit in Lakota mythology.

- Waziya, giant of the north winds who brings icy weather, famine, and diseases.

- Wiyohipeyata, god of the west winds who oversees endings and events of the night.

- Wiyohiyanpa, god of the east winds who oversees beginnings and events of the day.

- Yum, the whirlwind son of Anog Ite.

Navajo

[edit]- Niltsi, ally of the Heroic Twins and one of the guardians of the sun gods.[8]

Pawnee

[edit]- Hotoru, the giver of breath invoked in religious ceremonies.[9]

Central American and the Caribbean

[edit]Aztec

[edit]

- Cihuatecayotl, god of the west wind.

- Ehecatotontli, gods of the breezes.

- Ehecatl, god of wind.

- Mictlanpachecatl, god of the north wind.

- Tezcatlipoca, god of the night wind and hurricanes.

- Tlalocayotl, god of the east wind.

- Vitztlampaehecatl, god of the south wind.

Mayan

[edit]- Hurácan, K'iche' Maya creator god of the winds, storms and fire.

- Pauahtuns, wind deities associated with the Bacab and Chaac.

Taino

[edit]- Guabancex, goddess of the wind and hurricanes.

South America

[edit]Quechua

[edit]- Huayra-tata, god of the winds.

Brazil

[edit]- Iansã goddess of wind and air

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Coulter, Charles Russell; Turner, Patricia (2000). Encyclopedia of ancient deities. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn. ISBN 1-57958-270-2.

- ^ a b Budge, Ernest Alfred Wallis (1904). The Gods of the Egyptians: Or, Studies in Egyptian Mythology. Vol. 2. Methuen & Company. p. 296.

Miscellaneous Gods 2. The South Wind was called Shehbui, or...

- ^ Hall, Adelaide S. (1912). A Glossary of Important Symbols in Their Hebrew, Pagan & Christian Forms. Bates & Guild. p. 15.

- ^ Anthony S. Mercatante (1978). Who's who in Egyptian Mythology. C. N. Potter. p. 127.

- ^ Alfred Ernest Knight (1915). Amentet: An Account of the Gods, Amulets & Scarabs of the Ancient Egyptians (PDF). Longmans, Green. p. 133.

- ^ "Tipsywriter".

- ^ Yeats, William Butler, The Collected Poems, 1933 (First Scribner Paperback Poetry edition, 1996), ISBN 0-684-80731-9 "Sidhe is also Gaelic for wind, and certainly the Sidhe have much to do with the wind. They journey in whirling wind, the winds that were called the dance of the daughters of Herodias in the Middle Ages, Herodias doubtless taking the place of some old goddess. When old country people see the leaves whirling on the road they bless themselves, because they believe the Sidhe to be passing by." Yeats' Notes, p.454

- ^ "Navajo Myth (Clear)". 22 March 2012.

- ^ "The Path on the Rainbow: (A Pawnee Ceremony)".