Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Refraction

View on Wikipedia

In physics, refraction is the redirection of a wave as it passes from one medium to another. The redirection can be caused by the wave's change in speed or by a change in the medium.[1] Refraction of light is the most commonly observed phenomenon, but other waves such as sound waves and water waves also experience refraction. How much a wave is refracted is determined by the change in wave speed and the initial direction of wave propagation relative to the direction of change in speed.

Optical prisms and lenses use refraction to redirect light, as does the human eye. The refractive index of materials varies with the wavelength of light,[2] and thus the angle of the refraction also varies correspondingly. This is called dispersion and allows prisms[3] and raindrops in rainbows[4] to divide white light into its constituent spectral colors.

Law

[edit]

For light, refraction follows Snell's law, which states that, for a given pair of media, the ratio of the sines of the angle of incidence and angle of refraction is equal to the ratio of phase velocities in the two media, or equivalently, to the refractive indices of the two media:[5]

General explanation

[edit]

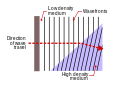

Refraction involves two related parts, both a result of the wave nature of light: a reduced speed in an optical medium and a change in angle when a wave front crosses between different media at an angle.

- Light slows as it travels through a medium other than vacuum (such as air, glass or water). This is not because of scattering or absorption. Rather it is because, as an electromagnetic oscillation, light itself causes other electrically charged particles such as electrons, to oscillate. The oscillating electrons emit their own electromagnetic waves which interact with the original light. The resulting combined wave has a lower speed. When light returns to a vacuum and there are no electrons nearby, this slowing effect ends and its speed returns to c.

- When light enters a slower medium at an angle, one side of the wavefront is slowed before the other. This asymmetrical slowing of the light causes it to change the angle of its travel. Once light is within the new medium with constant properties, it travels in a straight line again.

Slowing of light

[edit]As described above, the speed of light is slower in a medium other than vacuum. This slowing applies to any medium such as air, water, or glass, and is responsible for phenomena such as refraction. On the other side of the medium its speed will again be the speed of light in vacuum, c.

A correct explanation rests on light's nature as an electromagnetic wave.[6] Because light is an oscillating electrical/magnetic wave, light traveling in a medium causes the electrically charged electrons of the material to also oscillate. (The material's protons also oscillate but as they are around 2000 times more massive, their movement and therefore their effect, is far smaller). A moving electrical charge emits electromagnetic waves of its own. The electromagnetic waves emitted by the oscillating electrons interact with the electromagnetic waves that make up the original light, similar to water waves on a pond, a process known as constructive interference. When two waves interfere in this way, the resulting "combined" wave may have wave packets that pass an observer at a slower rate. The light has effectively been slowed. When the light leaves the material, this interaction with electrons no longer happens, and therefore the wave packet rate (and therefore its speed) return to normal.

Bending of light

[edit]Consider a wave going from one material to another where its speed is slower as in the figure. If it reaches the interface between the materials at an angle one side of the wave will reach the second material first, and therefore slow down earlier. With one side of the wave going slower the whole wave will pivot towards that side. This is why a wave will bend away from the surface or toward the normal when going into a slower material. In the opposite case of a wave reaching a material where the speed is higher, one side of the wave will speed up and the wave will pivot away from that side.

Another way of understanding the same thing is to consider the change in wavelength at the interface. When the wave goes from one material to another where the wave has a different speed v, the frequency f of the wave will stay the same, but the distance between wavefronts or wavelength λ = v/f will change. If the speed is decreased, such as in the figure to the right, the wavelength will also decrease. With an angle between the wave fronts and the interface and change in distance between the wave fronts the angle must change over the interface to keep the wave fronts intact. From these considerations the relationship between the angle of incidence θ1, angle of transmission θ2 and the wave speeds v1 and v2 in the two materials can be derived. This is the law of refraction or Snell's law and can be written as[7]

The phenomenon of refraction can in a more fundamental way be derived from the 2 or 3-dimensional wave equation. The boundary condition at the interface will then require the tangential component of the wave vector to be identical on the two sides of the interface.[8] Since the magnitude of the wave vector depend on the wave speed this requires a change in direction of the wave vector.

The relevant wave speed in the discussion above is the phase velocity of the wave. This is typically close to the group velocity which can be seen as the truer speed of a wave, but when they differ it is important to use the phase velocity in all calculations relating to refraction.

A wave traveling perpendicular to a boundary, i.e. having its wavefronts parallel to the boundary, will not change direction even if the speed of the wave changes.

Dispersion of light

[edit]

Refraction is also responsible for rainbows and for the splitting of white light into a rainbow-spectrum as it passes through a glass prism. Glass and water have higher refractive indexes than air. When a beam of white light passes from air into a material having an index of refraction that varies with frequency (and wavelength), a phenomenon known as dispersion occurs, in which different coloured components of the white light are refracted at different angles, i.e., they bend by different amounts at the interface, so that they become separated. The different colors correspond to different frequencies and different wavelengths.

On water

[edit]

Refraction occurs when light goes through a water surface since water has a refractive index of 1.33 and air has a refractive index of about 1. Looking at a straight object, such as a pencil in the figure here, which is placed at a slant, partially in the water, the object appears to bend at the water's surface. This is due to the bending of light rays as they move from the water to the air. Once the rays reach the eye, the eye traces them back as straight lines (lines of sight). The lines of sight (shown as dashed lines) intersect at a higher position than where the actual rays originated. This causes the pencil to appear higher and the water to appear shallower than it really is.

The depth that the water appears to be when viewed from above is known as the apparent depth. This is an important consideration for spearfishing from the surface because it will make the target fish appear to be in a different place, and the fisher must aim lower to catch the fish. Conversely, an object above the water has a higher apparent height when viewed from below the water. The opposite correction must be made by an archer fish.[9]

For small angles of incidence (measured from the normal, when sin θ is approximately the same as tan θ), the ratio of apparent to real depth is the ratio of the refractive indexes of air to that of water. But, as the angle of incidence approaches 90°, the apparent depth approaches zero, albeit reflection increases, which limits observation at high angles of incidence. Conversely, the apparent height approaches infinity as the angle of incidence (from below) increases, but even earlier, as the angle of total internal reflection is approached, albeit the image also fades from view as this limit is approached.

Atmospheric

[edit]

The refractive index of air depends on the air density and thus vary with air temperature and pressure. Since the pressure is lower at higher altitudes, the refractive index is also lower, causing light rays to refract towards the earth surface when traveling long distances through the atmosphere. This shifts the apparent positions of stars slightly when they are close to the horizon and makes the sun visible before it geometrically rises above the horizon during a sunrise.

Temperature variations in the air can also cause refraction of light. This can be seen as a heat haze when hot and cold air is mixed e.g. over a fire, in engine exhaust, or when opening a window on a cold day. This makes objects viewed through the mixed air appear to shimmer or move around randomly as the hot and cold air moves. This effect is also visible from normal variations in air temperature during a sunny day when using high magnification telephoto lenses and is often limiting the image quality in these cases. [10] In a similar way, atmospheric turbulence gives rapidly varying distortions in the images of astronomical telescopes limiting the resolution of terrestrial telescopes not using adaptive optics or other techniques for overcoming these atmospheric distortions.

Air temperature variations close to the surface can give rise to other optical phenomena, such as mirages and Fata Morgana. Most commonly, air heated by a hot road on a sunny day deflects light approaching at a shallow angle towards a viewer. This makes the road appear reflecting, giving an illusion of water covering the road.

In eye care

[edit]In medicine, particularly optometry, ophthalmology and orthoptics, refraction (also known as refractometry) is a clinical test in which a phoropter may be used by the appropriate eye care professional to determine the eye's refractive error and the best corrective lenses to be prescribed. A series of test lenses in graded optical powers or focal lengths are presented to determine which provides the sharpest, clearest vision.[11] Refractive surgery is a medical procedure to treat common vision disorders.

Mechanical waves

[edit]Water

[edit]

Water waves travel slower in shallower water. This can be used to demonstrate refraction in ripple tanks and also explains why waves on a shoreline tend to strike the shore close to a perpendicular angle. As the waves travel from deep water into shallower water near the shore, they are refracted from their original direction of travel to an angle more normal to the shoreline.[12]

Sound

[edit]In underwater acoustics, refraction is the bending or curving of a sound ray that results when the ray passes through a sound speed gradient from a region of one sound speed to a region of a different speed. The amount of ray bending is dependent on the amount of difference between sound speeds, that is, the variation in temperature, salinity, and pressure of the water.[13] Similar acoustics effects are also found in the Earth's atmosphere. The phenomenon of refraction of sound in the atmosphere has been known for centuries.[14] Beginning in the early 1970s, widespread analysis of this effect came into vogue through the designing of urban highways and noise barriers to address the meteorological effects of bending of sound rays in the lower atmosphere.[15]

Gallery

[edit]See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. "Refraction". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 2018-10-16.

- ^ R. Paschotta, article on chromatic dispersion Archived 2015-06-29 at the Wayback Machine in the Encyclopedia of Laser Physics and Technology Archived 2015-08-13 at the Wayback Machine, accessed on 2014-09-08

- ^ Carl R. Nave, page on Dispersion Archived 2014-09-24 at the Wayback Machine in HyperPhysics Archived 2007-10-28 at the Wayback Machine, Department of Physics and Astronomy, Georgia State University, accessed on 2014-09-08

- ^ "Rainbow". education.nationalgeographic.org. Retrieved 2025-06-28.

- ^ Born and Wolf (1959). Principles of Optics. New York, NY: Pergamon Press INC. p. 37.

- ^ Why does light slow down in water? - Fermilab

- ^ Hecht, Eugene (2002). Optics. Addison-Wesley. p. 101. ISBN 0-321-18878-0.

- ^ "Refraction". RP Photonics Encyclopedia. RP Photonics Consulting GmbH, Dr. Rüdiger Paschotta. Retrieved 2018-10-23.

It results from the boundary conditions which the incoming and the transmitted wave need to fulfill at the boundary between the two media. Essentially, the tangential components of the wave vectors need to be identical, as otherwise the phase difference between the waves at the boundary would be position-dependent, and the wavefronts could not be continuous. As the magnitude of the wave vector depends on the refractive index of the medium, the said condition can in general only be fulfilled with different propagation directions.

- ^ Dill, Lawrence M. (1977). "Refraction and the spitting behavior of the archerfish (Toxotes chatareus)". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 2 (2): 169–184. Bibcode:1977BEcoS...2..169D. doi:10.1007/BF00361900. JSTOR 4599128. S2CID 14111919.

- ^ "The effect of heat haze on image quality". Nikon. 2016-07-10. Retrieved 2018-11-04.

- ^ "Refraction". eyeglossary.net. Archived from the original on 2006-05-26. Retrieved 2006-05-23.

- ^ "Shoaling, Refraction, and Diffraction of Waves". University of Delaware Center for Applied Coastal Research. Archived from the original on 2009-04-14. Retrieved 2009-07-23.

- ^ Navy Supplement to the DOD Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms (PDF). Department Of The Navy. August 2006. NTRP 1-02.[dead link]

- ^ Mary Somerville (1840), On the Connexion of the Physical Sciences, J. Murray Publishers, (originally by Harvard University)

- ^ Hogan, C. Michael (1973). "Analysis of highway noise". Water, Air, & Soil Pollution. 2 (3): 387–392. Bibcode:1973WASP....2..387H. doi:10.1007/BF00159677. S2CID 109914430.

External links

[edit]- Reflections and Refractions in Ray Tracing, a simple but thorough discussion of the mathematics behind refraction and reflection.

- Flash refraction simulation- includes source, Explains refraction and Snell's Law.

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 23 (11th ed.). 1911. pp. 25–29.

Refraction

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition

Refraction is the change in direction of a propagating wave that results from a change in its transmission speed upon passing from one medium to another.[10] This phenomenon occurs for various types of waves, including electromagnetic waves such as light and mechanical waves like sound or water waves, provided the wave encounters a boundary between media with different wave speeds.[11] The bending happens only when the wave approaches the interface at an oblique angle; if incident normally, the wave continues straight without deviation.[10] For wave propagation across such boundaries, the frequency of the wave remains invariant, as it is determined by the source and conserved across the interface.[12] However, the speed changes due to the medium's properties, such as density or elasticity for mechanical waves, or permittivity and permeability for electromagnetic waves. Consequently, the wavelength adjusts to maintain the fundamental relation , resulting in a shorter wavelength in a medium where the wave slows down and a longer one where it speeds up.[12] The phenomenon of refraction was first observed and qualitatively described by ancient Greek scholars, with Claudius Ptolemy providing detailed accounts in his work Optics around 150 AD, including experimental attempts to measure the bending of light rays.[13] Ptolemy's descriptions focused on visual effects and rudimentary tables of angles, marking an early systematic study.[14] Although earlier attempts existed, including approximate tables by Ptolemy, the precise quantitative relationship was first established by Ibn Sahl in the 10th century and rediscovered in the 17th century through experiments by Willebrord Snell, later known as Snell's law.[15][16] A basic ray diagram for refraction depicts an incident ray striking the boundary between two media at an angle to the normal (a line perpendicular to the interface), bending to a refracted ray at angle , while the normal remains unchanged. The diagram typically shows the incident ray approaching from the first medium, the straight normal at the point of incidence, and the refracted ray departing into the second medium, illustrating the directional change without altering the wave's overall path if normal incidence occurs.Snell's Law

Snell's law, also known as the law of refraction, describes the relationship between the angles of incidence and refraction for a light ray passing from one medium to another. It states that the product of the refractive index of the first medium and the sine of the angle of incidence equals the product of the refractive index of the second medium and the sine of the angle of refraction:where and are the refractive indices of the respective media, is the angle between the incident ray and the normal to the interface, and is the angle between the refracted ray and the normal.[2] The refractive index of a medium is defined as the ratio of the speed of light in vacuum to the speed of light in that medium :

This quantity is dimensionless and greater than or equal to 1 for all media, with air having an approximate value of under standard conditions.[2][17] Snell's law can be derived from Fermat's principle, which posits that light travels along the path that minimizes the travel time between two points. Consider a light ray crossing a planar interface from medium 1 (speed ) to medium 2 (speed ). The time of travel for a path parameterized by the point of incidence is , where and are the path lengths in each medium. Minimizing with respect to the lateral displacement at the interface yields , or equivalently . Alternatively, the law follows from the continuity of wave fronts across the interface using Huygens' principle, ensuring phase matching at the boundary.[18] When light travels from a medium with higher refractive index to one with lower refractive index , a critical angle exists beyond which no refraction occurs into the second medium. This critical angle is given by

derived by setting in Snell's law. For incident angles , total internal reflection occurs, with the light entirely reflected back into the first medium at an angle equal to the incident angle, following the law of reflection.[19] A common example is light passing from air () to glass (). For an incident angle of , the refracted angle is . Conversely, from glass to air, the critical angle is , above which total internal reflection takes place.[20][21]

Light Refraction

Mechanism of Bending

Refraction occurs when a light wave passes from one medium to another with a different refractive index, causing the wave front to change direction due to a variation in propagation speed. According to Huygens' principle, every point on an advancing wave front serves as a source of secondary spherical wavelets, and the new wave front is the tangent envelope of these wavelets. In refraction, the differential speed between media leads to an asymmetric expansion of these wavelets: those entering the slower medium lag behind, resulting in an oblique propagation of the overall wave front and bending of the light ray.[22] Light travels more slowly in denser media, such as glass compared to air, because the electromagnetic wave interacts with the atoms or molecules, inducing oscillations that re-radiate secondary waves. These re-radiated waves interfere constructively with the incident wave in the forward direction but introduce a phase delay, effectively reducing the phase velocity of the light. The refractive index , where is the speed in vacuum and is the speed in the medium, quantifies this slowdown, with higher indicating stronger interactions and greater delay.[23] In ray optics, the incident ray strikes the interface at an angle, and upon entering a medium with higher refractive index, the refracted ray bends toward the normal (the perpendicular to the interface), while in a lower index medium, it bends away from the normal. This directional change maintains the continuity of the wave front across the boundary. At normal incidence, where the ray is perpendicular to the interface, no bending occurs despite the speed change, as the wave front advances uniformly. The resulting angular relationship, described by Snell's law, emerges directly from this mechanism of speed variation and wave front reconstruction. From a quantum perspective, light consists of photons, each carrying energy (where is Planck's constant and is frequency) and momentum , with the speed in the medium. During refraction, a photon's frequency—and thus energy—remains constant to conserve energy at the interface, but its momentum magnitude changes with the speed alteration. The component of momentum parallel to the interface is conserved, ensuring the photon adjusts its direction to satisfy this condition, analogous to a particle scattering while preserving parallel momentum.[24]Dispersion

Dispersion refers to the variation of the refractive index of a medium with the wavelength of light, causing different wavelengths to refract at slightly different angles. In most transparent media, such as glass or water, the refractive index decreases as the wavelength increases, a behavior known as normal dispersion. This wavelength dependence arises from the interaction of electromagnetic waves with the electrons in the material, leading to greater bending for shorter wavelengths (like blue light) compared to longer ones (like red light). As a result, white light passing through such media separates into its constituent colors, producing a spectrum.[25][3] An empirical relation often used to approximate this normal dispersion in the visible range is Cauchy's equation: where and are material-specific constants determined experimentally, with representing the refractive index at infinite wavelength and accounting for the dispersive contribution. This simple two-term form provides a good fit for many optical glasses away from absorption regions, though more complex models like the Sellmeier equation are used for broader spectral ranges. For example, in crown glass, typical values are and , yielding refractive indices around 1.52 for yellow light.[26][27] In prisms, this wavelength dependence manifests as angular dispersion, the spread in deviation angles between different colors. For a thin prism with apex angle , the deviation for a given wavelength is approximately , so the angular separation between blue and red light is . The dispersive power , a material property measuring the relative dispersion, is defined as , where is the mean refractive index (often for yellow light), typically ranging from 0.008 for low-dispersion crown glass to 0.017 for flint glass. This quantifies how effectively the material separates colors without excessive mean deviation.[28][29] A prominent natural example of dispersion is the formation of rainbows, where sunlight refracts, reflects, and disperses within spherical water droplets in the atmosphere. In the primary rainbow, each droplet causes one internal reflection, with dispersion separating the colors such that red appears on the outer edge (deviation angle about 42°) and violet on the inner edge (about 40°), forming an arc centered on the antisolar point. The secondary rainbow, fainter and higher in the sky, results from two internal reflections, reversing the color order (red inner, violet outer) with a larger deviation angle of about 51°. These phenomena require droplets of roughly 0.1–1 mm diameter and are observable when the sun is low.[30][31][32] Anomalous dispersion occurs in rare cases near regions of strong absorption, such as atomic resonance lines or molecular bands, where the refractive index increases with wavelength (). Here, the usual order of colors reverses, with longer wavelengths bending more than shorter ones, though this regime is accompanied by high absorption and limited transparency. This effect is described by the Kramers-Kronig relations linking real and imaginary parts of the dielectric function and is observed in gases like sodium vapor near the yellow D-lines or in certain dyed glasses.[33][34]Natural Phenomena

Atmospheric Refraction

Atmospheric refraction occurs due to the gradual variation in the refractive index of air with altitude, primarily caused by the decrease in air density as elevation increases. The refractive index of air near sea level is approximately 1.0003 under standard conditions, but it diminishes toward 1 at higher altitudes because lower density allows light to travel faster. This creates a vertical gradient in refractivity, bending light rays concave toward the Earth's surface and making celestial objects appear higher in the sky than their true positions.[35][36] One common everyday phenomenon is the apparent flattening of the Sun near the horizon at sunrise or sunset. As sunlight passes through the denser lower atmosphere, the rays from the Sun's upper edge bend less than those from the lower edge due to the increasing refractive index gradient near the ground, compressing the solar disk vertically and giving it an oblate shape.[37] Mirages represent more dramatic effects of this refraction, arising from horizontal temperature gradients that invert the usual density profile. An inferior mirage occurs when hot ground air creates a layer less dense than the air above, bending light rays upward and producing illusory images like puddles on a hot road, where the sky appears reflected below the actual object. In contrast, a superior mirage forms under a temperature inversion with colder air near the surface overlaid by warmer air, causing rays to bend downward and elevate distant objects, such as ships appearing to float above the horizon. Looming, a related distortion, magnifies and raises objects when the refractive gradient lifts the apparent horizon, often seen over cold water bodies.[38][39][40] In astronomy, atmospheric refraction necessitates corrections for the observed positions of stars and other celestial bodies, as it displaces their apparent altitude toward the zenith by up to about 35 arcminutes at the horizon. The angular correction can be approximated by the formula , where is the refractive index at sea level and is the true zenith distance; for small angles, this simplifies to , with the result in arcseconds. This effect is most pronounced for objects low on the horizon and requires adjustment in precise observations, such as navigation or astrometry.[41][42] The twinkling of stars, or scintillation, results from refraction through turbulent pockets of air with varying densities and temperatures, causing rapid fluctuations in the light's arrival angle and intensity. These small-scale atmospheric cells, driven by wind and convection, refract starlight irregularly, producing the characteristic shimmer, while planets appear steadier due to their larger apparent disks averaging out the distortions.[43][44] Temperature inversions, where warmer air traps cooler air below, exacerbate mirage formation by steepening the refractive index gradient and confining light paths to unusual trajectories. Such inversions are common in stable climatic conditions, like over polar seas or calm nights, enhancing superior mirages and contributing to optical illusions in regions with persistent cold surface layers.[40][45]Aquatic Refraction

Aquatic refraction occurs at the interface between water and air, where light bends due to the difference in refractive indices, leading to various optical illusions and adaptations in marine environments. The refractive index of water is approximately 1.33 for visible light, though it varies slightly with temperature, salinity, and wavelength; for instance, freshwater at 20°C has , while seawater can reach up to 1.34 due to dissolved salts.[46][47] This index governs how light rays from air enter water or vice versa, causing phenomena observable in everyday settings and underwater ecosystems. A classic example is the apparent depth of submerged objects, where an item at actual depth appears closer to the surface at , making pools or lakes seem shallower than they are; for water, this reduces perceived depth by about 25%.[48] Similarly, a straw or pencil partially immersed in a glass of water appears bent at the water's surface because light rays from the submerged portion refract toward the normal upon entering air, creating a discontinuity in the perceived straight line.[49] From underwater, this refraction culminates in Snell's window, a circular field of view spanning approximately 97° above the observer, beyond which total internal reflection occurs at the critical angle of , reflecting the underwater scene instead of the surface world.[50] In marine biology, refraction influences visual adaptations, particularly in fish vision, where spherical lenses with higher refractive indices compensate for the medium's properties to focus light effectively underwater, unlike the corneal-dominated focusing in air-breathing animals.[51] Deep-sea species further adapt to low-light conditions involving bioluminescence, with specialized photoreceptors and lens pigments enhancing detection of narrow-bandwidth blue-green emissions that propagate through water with minimal scattering, aided by the refractive environment.[52]Optical Applications

In Human Vision

Refraction plays a central role in human vision by bending light rays to focus them on the retina, primarily through the optical properties of the cornea and crystalline lens. The cornea, the eye's transparent front surface, has a refractive index of approximately 1.376 and contributes about 43 diopters to the total refractive power. The crystalline lens, with a refractive index of around 1.41, adds roughly 17 diopters, resulting in an overall refractive power of about 60 diopters for the relaxed eye. This combined refraction, governed by Snell's law at the air-cornea and cornea-aqueous humor interfaces, accounts for approximately two-thirds of the eye's focusing ability from the cornea alone. In a normal eye, known as emmetropia, parallel light rays from distant objects converge precisely on the retina, producing clear vision without accommodation. Refractive errors disrupt this process: myopia, or nearsightedness, occurs when the focal point falls in front of the retina due to an elongated eyeball or excessive corneal curvature, making distant objects blurry while near vision remains clear. Hyperopia, or farsightedness, results in the focal point behind the retina from a shortened eyeball or insufficient refractive power, often causing strain during near tasks. Astigmatism arises from irregular curvature of the cornea or lens, leading to multiple focal points and distorted vision at all distances. Corrective measures address these errors by altering the light path before it enters the eye or by modifying the eye's structure. Spectacles and contact lenses use thin lenses designed via the lensmaker's formula, , where is the focal length, is the lens material's refractive index, and , are the radii of curvature of the lens surfaces, to provide diverging power for myopia or converging power for hyperopia and astigmatism. LASIK surgery corrects refractive errors by using an excimer laser to reshape the cornea, flattening it for myopia or steepening it for hyperopia, thereby adjusting its refractive power without altering the lens. The eye's ability to focus on near objects, called accommodation, involves the ciliary muscles contracting to relax zonular fibers, allowing the lens to become more spherical and increase its refractive power by up to 10-12 diopters in youth. This dynamic refraction enables clear vision from infinity to about 25 cm. Presbyopia, an age-related condition typically onset after age 40, diminishes this capacity as the lens stiffens and loses elasticity, reducing accommodative amplitude to near zero by age 60 and necessitating reading glasses for close work. The development of corrective lenses traces back to the 13th century in Italy, where monks and scholars first crafted convex glass lenses to aid presbyopic reading, marking the earliest known optical correction for refractive errors.In Lenses and Instruments

Lenses are optical devices that exploit refraction to converge or diverge light rays, forming images through the bending of light at curved surfaces. Converging lenses, often convex in shape, have a positive focal length and focus parallel rays to a single point, while diverging lenses, typically concave, possess a negative focal length and cause parallel rays to spread apart. These effects arise from the variation in refractive index between the lens material and the surrounding medium, governed by Snell's law at each surface./University_Physics_III_-Optics_and_Modern_Physics(OpenStax)/02%3A_Geometric_Optics_and_Image_Formation/2.05%3A_Thin_Lenses) The behavior of thin lenses, where thickness is negligible compared to focal length, is described by the thin lens equation: Here, is the focal length, is the object distance, and is the image distance. This equation derives from applying Snell's law iteratively at the two refracting surfaces of the lens, combined with the paraxial approximation for small angles. The lensmaker's formula further relates to the lens's radii of curvature and , and refractive index : For a biconvex converging lens, and , yielding a positive ./University_Physics_III_-Optics_and_Modern_Physics(OpenStax)/02%3A_Geometric_Optics_and_Image_Formation/2.05%3A_Thin_Lenses)[53] Imperfections in lens performance, known as aberrations, degrade image quality. Chromatic aberration occurs because dispersion causes different wavelengths to refract by varying amounts, focusing them at different points along the optical axis. This is corrected in achromatic doublets, which combine a convex crown glass element (low dispersion) with a concave flint glass element (high dispersion) to bring two wavelengths to the same focus. Spherical aberration, meanwhile, results from the stronger refraction at the lens periphery compared to the center for spherical surfaces, blurring the image. Aspheric lenses, with non-spherical surfaces, mitigate this by tailoring the curvature to equalize focal points across the aperture.[54][55] In microscopes, refraction through objective and eyepiece lenses enables high linear magnification. The objective forms a real, magnified intermediate image with magnification , where and are the image and object distances from the thin lens equation. The total magnification is then the product of the objective's linear magnification and the eyepiece's angular magnification, often achieving hundreds to thousands of times enlargement for detailed specimen viewing. Telescopes utilize refraction to achieve angular magnification, expanding the apparent size of distant objects. In a refracting telescope, the angular magnification is , where and are the focal lengths of the objective and eyepiece lenses, respectively, allowing resolution of fine celestial details./University_Physics_III_-Optics_and_Modern_Physics(OpenStax)/02%3A_Geometric_Optics_and_Image_Formation/2.09%3A_Microscopes_and_Telescopes)[56] Fiber optics rely on refraction via total internal reflection to guide light signals over long distances. The fiber core, with a higher refractive index than the surrounding cladding (), confines light within the core when the incidence angle exceeds the critical angle, defined by Snell's law as . This principle enables low-loss transmission in telecommunications, with typical index differences of about 0.01 for single-mode fibers.[57][58]Mechanical Waves

Water Waves

Refraction of surface water waves occurs when waves propagate from regions of one water depth to another, causing a change in wave direction due to variations in wave speed. This phenomenon is prominent in oceans, coastal areas, and even laboratory ripple tanks, where waves encounter gradually changing depths. The bending of wave crests aligns them more perpendicular to the depth contours, altering the distribution of wave energy along the shore.[59]/05:_Coastal_hydrodynamics/5.02:_Wave_transformation/5.2.3:_Refraction) The speed of surface gravity waves depends on water depth relative to the wavelength. In deep water, where the depth is greater than half the wavelength , the phase speed is given by where is the acceleration due to gravity; this speed is independent of depth. In shallow water, where , the speed simplifies to which depends solely on depth and decreases as water shallows. These relations arise from the dispersion relation for gravity waves, describing how wave propagation varies with depth.[60][61] As waves approach shallower regions, such as near a beach, their speed reduces in those areas, causing the part of the wave crest in shallower water to lag behind the part in deeper water. This differential slowing results in the wave crests bending or refracting toward the normal to the depth contour lines, effectively turning the waves more directly toward the shore. For instance, oblique waves approaching a straight beach will refract such that their crests become nearly parallel to the shoreline, concentrating energy perpendicularly onto the beach. This mechanism is analogous to the bending observed in light refraction but applied to mechanical waves.[59]/05:_Coastal_hydrodynamics/5.02:_Wave_transformation/5.2.3:_Refraction) The refraction process can be understood through Huygens' principle, which posits that every point on a wave front acts as a source of secondary spherical wavelets that propagate forward at the local wave speed, with the new wave front forming as the envelope tangent to these wavelets. In varying depths, wavelets in shallower water expand more slowly than those in deeper water, causing the overall front to pivot and adjust its direction. This adjustment ensures continuity of the wave phase across the front, leading to the observed bending without altering the wave frequency./University_Physics_III_-Optics_and_Modern_Physics(OpenStax)/01:_The_Nature_of_Light/1.07:_Huygenss_Principle) One notable phenomenon resulting from water wave refraction is harbor resonance, where incoming waves at frequencies matching the harbor's natural oscillation modes amplify inside the enclosed or semi-enclosed basin, potentially causing significant water level fluctuations and structural stress. Refraction also contributes to wave focusing along irregular coastlines, where wave energy converges on protruding headlands, enhancing local erosion rates while dispersing energy in adjacent bays. For example, in headland-bay systems, refracted waves increase height and power at headlands, accelerating cliff retreat and sediment removal.[62]/13:_Coastal_Oceanography/13.03:_Landforms_of_Coastal_Erosion) During refraction, the wave frequency remains constant as it is determined by the distant source, such as wind or a wave maker, but the wavelength shortens in slower (shallower) regions to maintain the relation , where is frequency. This compression of wavefronts in shallow areas further intensifies local wave steepness and breaking, contributing to energy dissipation and sediment transport patterns.[59][60]Sound Waves

Refraction of sound waves occurs when acoustic waves propagate through media with spatial variations in sound speed, causing the waves to bend according to gradients in temperature, density, or wind velocity.[63] The speed of sound in air is primarily dependent on temperature, approximated by the formula m/s, where is the temperature in degrees Celsius; this speed is higher in warmer media due to increased molecular kinetic energy facilitating faster pressure wave propagation.[64] In seawater, sound speed typically ranges from about 1500–1530 m/s in surface waters, decreasing to a minimum of around 1480 m/s in the SOFAR channel at approximately 1000 m depth due to temperature gradients in the thermocline, and then increasing to higher values in deeper layers primarily due to pressure effects.[65] These speed variations lead to curved propagation paths for sound rays, analogous to light rays in optics. In atmospheric conditions with a decreasing temperature gradient with height—such as over hot ground during the day—the sound speed decreases upward, causing rays to refract upward and away from the surface, creating regions of reduced audibility known as shadow zones.[66] Conversely, in temperature inversions where temperature (and thus sound speed) increases with height—often over cold surfaces at night—rays bend downward toward the ground, extending the range of sound propagation.[67] Wind gradients can further influence refraction by adding an effective speed component, bending rays downwind or upwind depending on the shear.[68] Notable phenomena arise from these refractions. Auditory mirages occur when temperature or density gradients distort the apparent location of a sound source, similar to optical mirages but for hearing; for instance, snow cover can refract vole calls, misleading predators like owls about prey position.[69] In ocean acoustics, shadow zones form where rays are refracted away from receivers due to thermoclines—layers of rapid temperature change—preventing sound from reaching certain areas and aiding submarine concealment.[70] The SOFAR (Sound Fixing and Ranging) channel, a deep-ocean layer around 1000 m where sound speed reaches a minimum due to pressure and temperature effects, traps low-frequency sound waves, allowing them to propagate thousands of kilometers with minimal loss by refracting rays back toward the axis.[65] In the ray acoustics approximation, valid for high frequencies where wavelengths are short compared to inhomogeneities, sound propagation follows paths governed by an analog of Snell's law: , where is the ray angle to the gradient normal and is the local sound speed; this is equivalent to an effective refractive index , with a reference speed, mirroring optical behavior but scaled by acoustic velocities.[71] This framework predicts ray tracing in varying media, essential for modeling complex environments. Such refractions have practical applications in sonar systems, where beam bending in ocean layers like thermoclines or the SOFAR channel affects detection ranges, convergence zones (focusing sound energy), and shadow avoidance strategies for underwater navigation and target tracking.[72]References

- https://www.coastalwiki.org/wiki/Shallow-water_wave_theory

- https://www.coastalwiki.org/wiki/Harbor_resonance