Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Presbyopia

View on Wikipedia

| Presbyopia | |

|---|---|

| Other names | The aging eye condition[1] |

| |

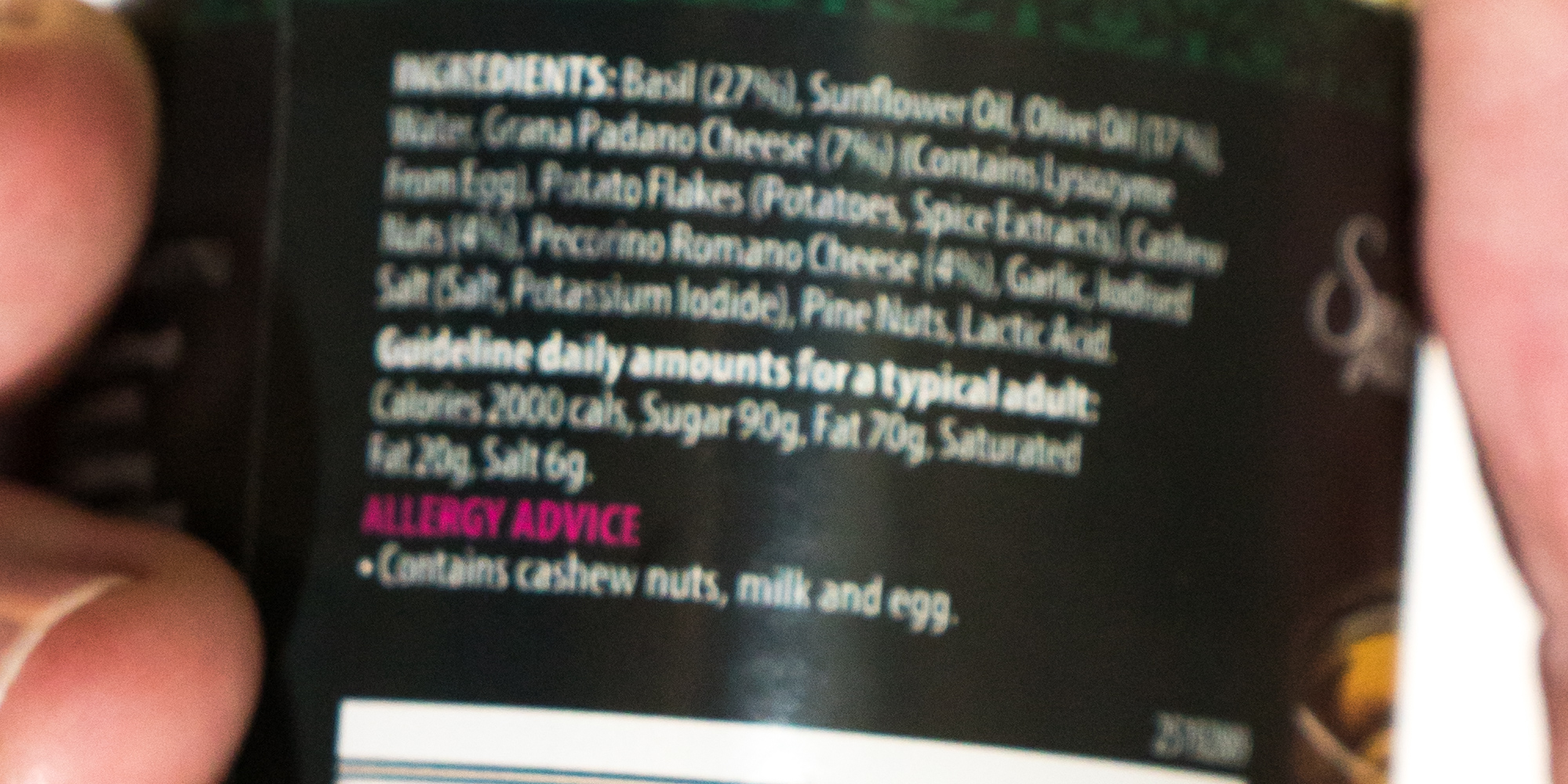

| A person with presbyopia cannot easily read the small print of an ingredients list (top), which appear clearer to someone without presbyopia (bottom). | |

| Specialty | Optometry, ophthalmology |

| Symptoms | Difficulty reading small print, having to hold reading material farther away, headaches, eyestrain[1] |

| Usual onset | Progressively worsening in those over 40 years old[1] |

| Causes | Aging-related stiffening of the lens of the eye[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Eye exam[1] |

| Treatment | Eyeglasses,[1] contact lenses[2] |

| Frequency | 25% currently;[3] all eventually affected[1] |

Presbyopia is a physiological insufficiency of optical accommodation associated with the aging of the eye; it results in progressively worsening ability to focus clearly on close objects.[4] Also known as age-related farsightedness[5] (or as age-related long sight in the UK[6]), it affects many adults over the age of 40. A common sign of presbyopia is difficulty in reading small print, which results in having to hold reading material farther away. Other symptoms associated can be headaches and eyestrain.[4] Different people experience different degrees of problems.[1] Other types of refractive errors may exist at the same time as presbyopia.[1] While exhibiting similar symptoms of blur in the vision for close objects, this condition has nothing to do with hypermetropia or far-sightedness, which is almost invariably present in newborns and usually decreases as the newborn gets older.

Presbyopia is a typical part of the aging process.[4] It occurs due to age-related changes in the lens (decreased elasticity and increased hardness) and ciliary muscle (decreased strength and ability to move the lens), causing the eye to focus light right behind rather than on the retina when looking at close objects.[4] It is a type of refractive error, along with nearsightedness, farsightedness, and astigmatism.[4] Diagnosis is by an eye examination.[4]

Presbyopia can be corrected using glasses, contact lenses, multifocal intraocular lenses, or LASIK (PresbyLASIK) surgery.[2][7][4] The most common treatment is glass correction using appropriate convex lens. Glasses prescribed to correct presbyopia may be simple reading glasses, bifocals, trifocals, or progressive lenses.[4]

People over 40 are at risk for developing presbyopia and all people become affected to some degree.[1] An estimated 25% of people (1.8 billion globally) had presbyopia as of 2015[update].[3]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]The first symptoms most people notice are difficulty reading fine print, particularly in low light conditions; eyestrain when reading for a long period; and blurring of near objects or temporarily blurred vision when changing the viewing distance. Many extreme presbyopes complain that their arms have become "too short" to hold reading material at a comfortable distance.[citation needed]

Presbyopia, like other focal imperfections, becomes less noticeable in bright sunlight when the pupil becomes smaller.[8] As with any lens, increasing the focal ratio of the lens increases depth of field by reducing the level of blur of out-of-focus objects (compare the effect of aperture on depth of field in photography).

The onset of presbyopia varies among those with certain professions and those with miotic pupils.[9] In particular, farmers and homemakers seek correction later, whereas service workers and construction workers seek correction earlier. Scuba divers with interest in underwater photography may notice presbyopic changes while diving before they recognize the symptoms in their normal routines due to the near focus in low light conditions.[10]

Interaction with myopia

[edit]People with low near-sightedness can read comfortably without eyeglasses or contact lenses even after age forty, but higher myopes might require two pairs of glasses (one for distance, one for near), bifocal, or progressive lenses. However, their myopia does not disappear and the long-distance visual challenges remain. Myopes considering refractive surgery are advised that surgically correcting their nearsightedness may be a disadvantage after age forty, when the eyes become presbyopic and lose their ability to accommodate or change focus, because they will then need to use glasses for reading. Myopes with low astigmatism find near vision better, though not perfect, without glasses or contact lenses when presbyopia sets in, but the more astigmatism, the poorer the uncorrected near vision.[citation needed]

A surgical technique offered is to create a "reading eye" and a "distance vision eye", a technique commonly used in contact lens practice, known as monovision. Monovision can be created with contact lenses, so candidates for this procedure can determine if they are prepared to have their corneas reshaped by surgery to cause this effect permanently.[citation needed]

Mechanism

[edit]

The cause of presbyopia is lens stiffening by decreasing levels of α-crystallin, a process which may be sped up by higher temperatures.[11] It results in a near point greater than 25 cm[12] (or equivalently, less than 4 diopters).

In optics, the closest point at which an object can be brought into focus by the eye is called the eye's near point. A standard near point distance of 25 cm is typically assumed in the design of optical instruments, and in characterizing optical devices such as magnifying glasses.[citation needed]

There is some confusion over how the focusing mechanism of the eye works.[clarification needed] In the 1977 book, Eye and Brain,[13] for example, the lens is said to be suspended by a membrane, the 'zonula', which holds it under tension. The tension is released, by contraction of the ciliary muscle, to allow the lens to become more round, for close vision. This implies the ciliary muscle, which is outside the zonula, must be circumferential, contracting like a sphincter, to slacken the tension of the zonula pulling outwards on the lens. This is consistent with the fact that our eyes seem to be in the 'relaxed' state when focusing at infinity, and also explains why no amount of effort seems to enable a myopic person to see farther away.[citation needed]

The ability to focus on near objects declines throughout life, from an accommodation of about 20 dioptres (ability to focus at 50 mm away) in a child, to 10 dioptres at age 25 (100 mm), and levels off at 0.5 to 1 dioptre at age 60 (ability to focus down to 1–2 m only). The expected, maximum, and minimum amplitudes of accommodation in diopters (D) for a corrected patient of a given age can be estimated using Hofstetter's formulas: expected amplitude (D) = 18.5 − 0.3 × (age in years); maximum amplitude (D) = 25 − 0.4 × (age in years); minimum amplitude (D) = 15 − 0.25 × (age in years).[15]

A basic eye exam, which includes a refraction assessment and an eye health exam, is used to diagnose presbyopia.

Treatment

[edit]Images captured by the eye are translated into electric signals that are transmitted to the brain where they are interpreted. Presbyopia can be addressed in two components of the visual system, either improving the capturing of images by the eyes, or (in principle) image processing in the brain. Eye treatments include corrective lenses, eye drops, and surgery.

Corrective lenses

[edit]Corrective lenses provide vision correction over a range as high as +4.0 diopters. People with presbyopia require a convex lens for reading glasses; specialized preparations of convex lenses usually require the services of an optometrist.[16]

Contact lenses can also be used to correct the focusing loss that comes along with presbyopia. Multifocal contact lenses can be used to correct vision for both the near and the far. Some people choose contact lenses to correct one eye for near and one eye for far with a method called monovision.

Eye drops

[edit]Pilocarpine, administered by eye drops that constrict the pupil, has been approved by the US FDA for presbyopia.[17][18] Research on other drugs is in progress.[19] Eye drops intended to restore lens elasticity are also being investigated.[20]

Surgery

[edit]Refractive surgery has been done to create multifocal corneas.[21] PresbyLASIK, a type of multifocal corneal ablation LASIK procedure may be used to correct presbyopia. Results are, however, more variable and some people have a decrease in visual acuity.[22] Concerns with refractive surgeries for presbyopia include people's eyes changing with time.[21] Other side effects of multifocal corneal ablation include postoperative glare, halos, ghost images, and monocular diplopia.[23]

Image processing in the brain

[edit]A number of studies have claimed improvements in near visual acuity by the use of training protocols based on perceptual learning and requiring the detection of briefly presented low-contrast Gabor stimuli; study participants with presbyopia were enabled to read smaller font sizes and to increase their reading speed.[24][25][26][27]

Etymology

[edit]The term presbyopia derives from Ancient Greek: πρέσβυς, romanized: presbys, lit. 'old' and ὤψ, ōps, 'sight' (GEN ὠπός, ōpos).[28][29]

History

[edit]The condition was mentioned as early as the writings of Aristotle in the 4th century BC.[30] Glass lenses first came into use for the problem in the late 13th century.[30]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Facts About Presbyopia". National Eye Institute. October 2010. Archived from the original on 4 October 2016. Retrieved 11 September 2016.

- ^ a b Pérez-Prados, Roque; Piñero, David P; Pérez-Cambrodí, Rafael J; Madrid-Costa, David (March 2017). "Soft multifocal simultaneous image contact lenses: a review". Clinical and Experimental Optometry. 100 (2): 107–127. doi:10.1111/cxo.12488. PMID 27800638. S2CID 205049139.

- ^ a b Fricke, Timothy R.; Tahhan, Nina; Resnikoff, Serge; Papas, Eric; Burnett, Anthea; Ho, Suit May; Naduvilath, Thomas; Naidoo, Kovin S. (October 2018). "Global Prevalence of Presbyopia and Vision Impairment from Uncorrected Presbyopia". Ophthalmology. 125 (10): 1492–1499. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2018.04.013. hdl:1959.4/unsworks_79548. PMID 29753495.

We estimate there were 1.8 billion people (prevalence, 25%; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.7–2.0 billion [23%–27%]) globally with presbyopia in 2015 [...].

- ^ a b c d e f g h Khurana, AK (September 2008). "Asthenopia, anomalies of accommodation and convergence". Theory and practice of optics and refraction (2nd ed.). Elsevier. pp. 100–107. ISBN 978-81-312-1132-8.

- ^ "5 Facts About Age-Related Farsightedness You Probably Didn't Know". www.webmd.com. Retrieved 2 February 2022.

- ^ "Age-related Long Sight". patient.info. Retrieved 2 February 2022.

- ^ "PresbyLASIK - EyeWiki". eyewiki.aao.org. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

- ^ "Presbyopia: Patient Information". Marquette, MI: Eye Associates of Marquette. 2008. Archived from the original on 2 December 2008. Retrieved 31 October 2010.

- ^ García Serrano, JL; López Raya, R; Mylonopoulos Caripidis, T (November 2002). "Variables related to the first presbyopia correction" (Free full text). Archivos de la Sociedad Española de Oftalmología. 77 (11): 597–604. ISSN 0365-6691. PMID 12410405. Archived from the original on 7 October 2011.

- ^ Bennett QM (June 2008). "New thoughts on the correction of presbyopia for divers". Diving Hyperb Med. 38 (2): 163–164. PMID 22692711. Archived from the original on 19 April 2013. Retrieved 19 April 2013.

- ^ Pathai, S; Shiels, PG; Lawn, SD; Cook, C; Gilbert, C (March 2013). "The eye as a model of ageing in translational research--molecular, epigenetic and clinical aspects". Ageing Research Reviews. 12 (2): 490–508. doi:10.1016/j.arr.2012.11.002. PMID 23274270. S2CID 26015190.

- ^ Katz, Debora M. (2015). Physics for Scientists and Engineers: Foundations and Connections, Advance Edition. Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-1-305-53720-0.

- ^ Gregory, Richard Langton (1977). Eye and brain : the psychology of seeing (3rd ed. rev. and update. ed.). New York; Toronto: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0070246652.

- ^ Duane, Alexander (1922). "Studies in Monocular and Binocular Accommodation with their Clinical Applications". American Journal of Ophthalmology. 5 (11): 865–877. doi:10.1016/s0002-9394(22)90793-7. S2CID 43172462.

- ^ Robert P. Rutstein, Kent M. Daum, Anomalies of Binocular Vision: Diagnosis & Management, Mosby, 1998.

- ^ Li, G; Mathine, DL; Valley, P; Ayräs, P; Haddock, JN; Giridhar, MS; Williby, G; Schwiegerling, J; et al. (April 2006). "Switchable electro-optic diffractive lens with high efficiency for ophthalmic applications". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 103 (16): 6100–4. Bibcode:2006PNAS..103.6100L. doi:10.1073/pnas.0600850103. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 1458838. PMID 16597675.

- ^ Moyer, Melinda Wenner (14 December 2021). "New Eye Drops Offer an Alternative to Reading Glasses". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 15 December 2021.

- ^ "Vuity". drugs.com. Retrieved 9 February 2022.

- ^ Dick, HB (July 2019). "Small-aperture strategies for the correction of presbyopia". Current Opinion in Ophthalmology. 30 (4): 236–242. doi:10.1097/ICU.0000000000000576. PMID 31033734. S2CID 139101960.

- ^ Korenfeld, Michael S.; Robertson, Stella M.; Stein, Jerry M.; Evans, David G.; Rauchman, Steven H.; Sall, Kenneth N.; Venkataraman, Subha; Chen, Bee-Lian; Wuttke, Mark; Burns, William (29 January 2021). "Topical lipoic acid choline ester eye drop for improvement of near visual acuity in subjects with presbyopia: a safety and preliminary efficacy trial". Eye. 35 (12): 3292–3301. doi:10.1038/s41433-020-01391-z. PMC 8602643. PMID 33514891.

- ^ a b Kim, Tae-im; del Barrio, Jorge L Alió; Wilkins, Mark; Cochener, Beatrice; Ang, Marcus (May 2019). "Refractive surgery". The Lancet. 393 (10185): 2085–2098. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)33209-4. PMID 31106754. S2CID 4474834.

- ^ Pallikaris IG, Panagopoulou SI (July 2015). "PresbyLASIK approach for the correction of presbyopia". Current Opinion in Ophthalmology. 26 (4): 265–72. doi:10.1097/icu.0000000000000162. PMID 26058023. S2CID 35434343.

- ^ Azar, Dimitri T. (2007). "Terminology, classification, and history of refractive surgery". Refractive surgery (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: Mosby / Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-323-03599-6. OCLC 853286620.

- ^ Lev M, Ludwig K, Gilaie-Dotan S, et al. (28 November 2014). "Training improves visual processing speed and generalizes to untrained functions". Scientific Reports. 4 (1): 7251. Bibcode:2014NatSR...4.7251L. doi:10.1038/srep07251. PMC 4246693. PMID 25431233.

- ^ Polat U, Schor C, Tong J, Zomet A, Lev M, Yehezkel O, Sterkin A, Levi DM (23 February 2012). "Training the brain to overcome the effect of aging on the human eye". Scientific Reports. 2: 278. Bibcode:2012NatSR...2..278P. doi:10.1038/srep00278. PMC 3284862. PMID 22363834.

- ^ DeLoss DJ, Watanabe T, Andersen GJ (2014). "Optimization of perceptual learning: Effects of task difficulty and external noise in older adults". Vision Research. 99: 37–45. doi:10.1016/j.visres.2013.11.003. PMC 4029927. PMID 24269381.

- ^ Sterkin A, Levy Y, Pokroy R, Lev M, Levian L, Doron R, Yehezkel O, Fried M, Frenkel-Nir Y, Gordon B, Polat U (2018). "Vision improvement in pilots with presbyopia following perceptual learning". Vision Research. 152 (152): 61–73. doi:10.1016/j.visres.2017.09.003. PMID 29154795. S2CID 20260936.

- ^ "Presbyopia". Dictionary.reference.com. Archived from the original on 12 April 2013. Retrieved 19 April 2013.

- ^ "Presbyopia". Etymonline.com. Archived from the original on 18 August 2017. Retrieved 4 May 2017.

- ^ a b Wade, Nicholas J. (2000). A Natural History of Vision. MIT Press. p. 50. ISBN 9780262731294. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

External links

[edit]- "Presbyopia" at MedLinePlus Medical Encyclopedia