Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

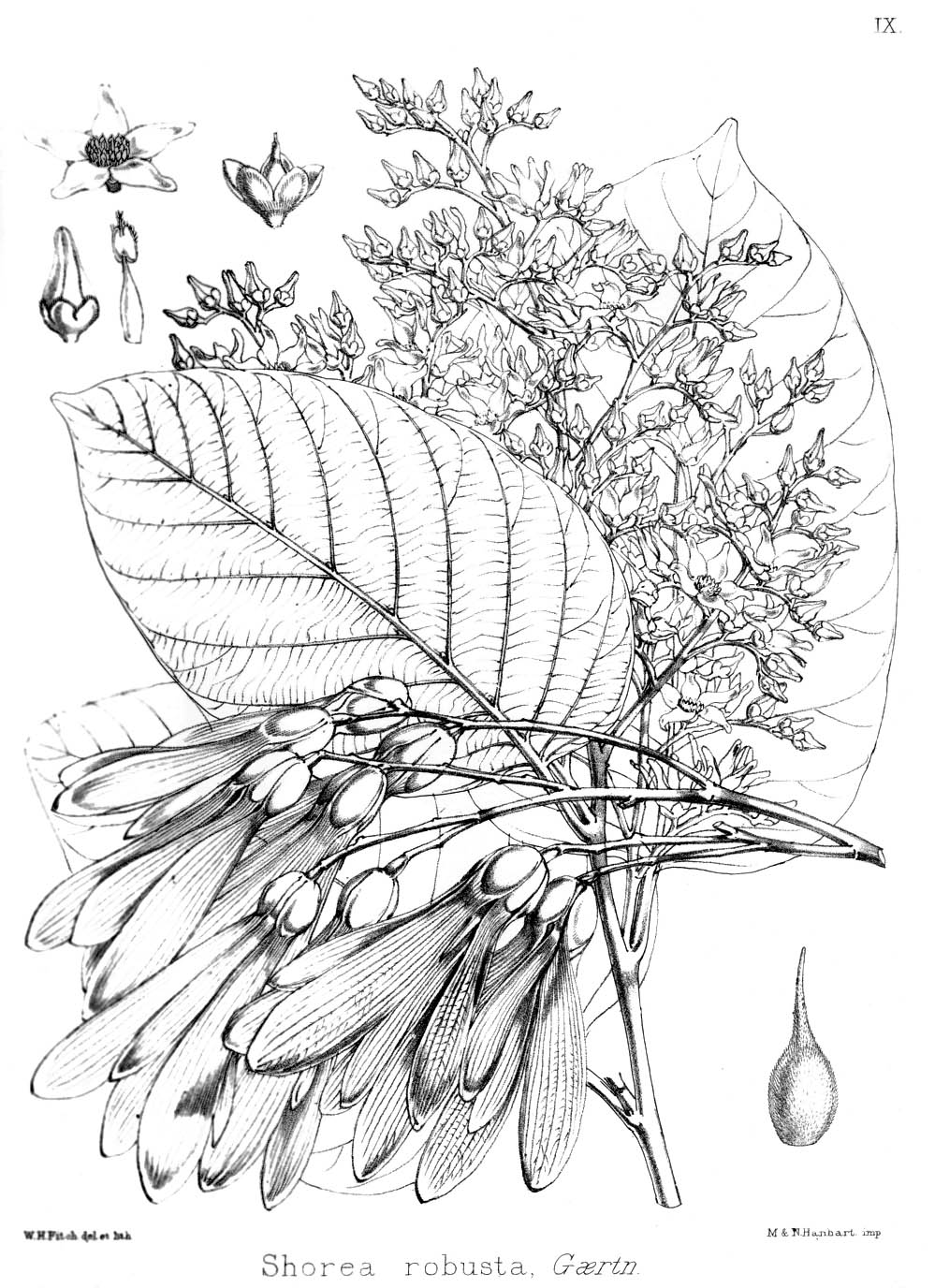

Shorea robusta

View on Wikipedia

| Shorea robusta | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Malvales |

| Family: | Dipterocarpaceae |

| Genus: | Shorea |

| Species: | S. robusta

|

| Binomial name | |

| Shorea robusta | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Vatica robusta | |

Shorea robusta, the sal tree,[2] sāla, shala, sakhua,[3] or sarai,[4] is a species of tree in the family Dipterocarpaceae. The tree is native to India, Bangladesh, Nepal, Tibet and across the Himalayan regions.[5]

Evolution

[edit]Fossil evidence from lignite mines in the Indian states of Rajasthan and Gujarat indicate that sal trees (or at least a closely related Shorea species) have been a dominant tree species of forests of the Indian subcontinent since at least the early Eocene (roughly 49 million years ago), at a time when the region otherwise supported a very different biota from the modern day. Evidence comes from the numerous amber nodules in these rocks, which originate from the dammar resin produced by the sal trees.[6]

Description

[edit]

Shorea robusta can grow up to 40 metres (130 feet) tall with a trunk diameter of 2 metres (6.6 feet).[7] The leaves are 10–25 cm long and 5–15 cm broad. In wetter areas, sal is evergreen; in drier areas, it is dry-season deciduous, shedding most of the leaves from February to April, leafing out again in April and May.

The sal tree is known also as sakhua in northern India, including Madhya Pradesh, Odisha and Jharkhand.[8][9] It is the state tree of two Indian states – Chhattisgarh and Jharkhand.[10][circular reference]

Distribution and habitat

[edit]This tree is native to the Indian subcontinent, ranging south of the Himalaya, from Myanmar in the east to Nepal, India and Bangladesh. In India, it extends from Chhattisgarh, Assam, Bengal, Odisha and Jharkhand west to the Shivalik Hills in Haryana, east of the Yamuna. The range also extends through the Eastern Ghats and to the eastern Vindhya and Satpura ranges of central India.[11] It is often the dominant tree in the forests where it occurs. In Nepal, it is found mostly in the Terai region from east to west, especially, in the Sivalik Hills (Churia Range) in the subtropical climate zone. There are many protected areas, such as Chitwan National Park, Bardia National Park and Shuklaphanta National Park, where there are dense forests of huge sal trees. It is also found in the lower belt of the Hilly region and Inner Terai.

Culture

[edit]Hinduism

[edit]In Hindu tradition, the sal tree is sacred. The tree is also associated with Vishnu.[12] The tree's common name, sal, comes from the word shala, which means 'rampart' in Sanskrit.[12]

Jains state that the 24th tirthankara, Mahavira, achieved enlightenment under a sal.[citation needed]

Some cultures in Bengal worship Sarna Burhi, a goddess associated with sacred groves of Sal trees.[13]

There is a standard decorative element of Hindu Indian sculpture which originated in a yakshini grasping the branch of a flowering tree while setting her foot against its roots.[14] This decorative sculptural element was integrated into Indian temple architecture as salabhanjika or "sal tree maiden", although it is not clear either whether it is a sal tree or an asoka tree.[15] The tree is also mentioned in the Ramayana—specifically, where Lord Rama (on request of deposed monkey-king Sugriva for proof he can kill Sugriva's older half-brother Vali) is asked to pierce seven sals in a row with a single arrow (which is later used to kill Vali, and still later to behead Ravana's brother Kumbhakarna)

In the Kathmandu Valley of Nepal, one can find typical Nepali pagoda temple architectures with very rich wooden carvings, and most of the temples, such as Nyatapola Temple, are made of bricks and sal tree wood.[citation needed]

Buddhism

[edit]

Buddhist tradition holds that Queen Māyā of Sakya, while en route to her grandfather's kingdom, gave birth to Gautama Buddha while grasping the branch of a sal tree or an Ashoka tree in a garden in Lumbini in south Nepal.[16][17]

Also according to Buddhist tradition, the Buddha was lying between a pair of sal trees when he died:

Then the Blessed One with a large community of monks went to the far shore of the Hiraññavati River and headed for Upavattana, the Mallans' sal-grove near Kusinara. On arrival, he said to Ven. Ananda, "Ananda, please prepare a bed for me between the twin sal-trees, with its head to the north. I am tired, and will lie down."[18]

The sal tree is also said to have been the tree under which Koṇḍañña and Vessabhū, respectively the fifth and twenty-fourth Buddhas preceding Gautama Buddha, attained enlightenment.

In Buddhism, the brief flowering of the sal tree is used as a symbol of impermanence and the rapid passing of glory, particularly as an analog of sic transit gloria mundi. In Japanese Buddhism, this is best known through the opening line of The Tale of the Heike – a tale of the rise and fall of a once-powerful clan – whose latter half reads "the color of the sāla flowers reveals the truth that the prosperous must decline." (沙羅雙樹の花の色、盛者必衰の理を顯す, sharasōju no hana no iro, jōshahissui no kotowari wo arawasu),[19] quoting the four-character idiom jōsha hissui (盛者必衰) from a passage in the Humane King Sutra, "The prosperous inevitably decline, the full inevitably empty" (盛者必衰、実者必虚, jōsha hissui, jissha hikkyo?).

Confusion with cannonball tree and other trees

[edit]In Asia, the sal tree is often confused with the Couroupita guianensis or cannonball tree, a tree from tropical South America introduced to Asia by the British in the 19th century. The cannonball tree has since then been planted at Buddhist and Hindu religious sites in Asia in the belief that it is the tree of sacred scriptures. In Sri Lanka, Thailand and other Theravada Buddhist countries it has been planted at Buddhist monasteries and other religious sites. In India the cannonball tree has been planted at Shiva temples and is called Shiv Kamal or Nagalingam since its flowers are said to resemble the hood of a Nāga (divine cobra) protecting a Shiva lingam.[17][20] An example of a cannonball tree erroneously named 'sal tree' is at the Pagoda at the Royal Palace of Phnom Penh in Cambodia.[21]

In Japan the sal tree of Buddhist scriptures is identified as the deciduous camellia (Stewartia pseudocamellia), called shāra, 沙羅, from Sanskrit śāla.[17]

The sal tree is also said to be confused with the Ashoka tree (Saraca asoca).[22]

Uses

[edit]Sal is one of the most important sources of hardwood timber in India, with hard, coarse-grained wood that is light in colour when freshly cut, but becomes dark brown with exposure. The wood is resinous and durable, and is sought after for construction, although not well suited to planing and polishing. The wood is especially suitable for constructing frames for doors and windows.

The dry leaves of sal are a major source for the production of leaf plates and bowls called patravali in India and Nepal. The used leaves/plates are readily eaten by goats and cattle. In Nepal, its leaves are used to make local plates and vessels called "tapari", "doona" and "bogata" in which rice and curry is served. However, the use of such "natural" tools have sharply declined during the last decade.[citation needed]

Sal tree resin is known as sal dammar or Indian dammar,[23] ṛla in Sanskrit. It is used as an astringent in Ayurvedic medicine,[24] burned as incense in Hindu ceremonies, and used to caulk boats and ships.[23]

Sal seeds and fruit are a source of lamp oil and vegetable fat. The seed oil is extracted from the seeds and used as cooking oil after refining.

Gallery

[edit]-

Sal forests in Dehradun, India

-

Sal trunk constricted by a ficus tree at Jayanti

-

New leaves with flower buds West Bengal, India

-

Old leaf at Jayanti

-

Sal tree in full bloom at Gazipur, Bangladesh

-

Salabhanjika or "sal tree maiden", Hoysala sculpture, Belur, Karnataka

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Ashton, P. (1998). "Shorea robusta". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 1998 e.T32097A9675160. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.1998.RLTS.T32097A9675160.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ "Shorea robusta". Germplasm Resources Information Network. Agricultural Research Service, United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 11 May 2019.

- ^ M. S. Swaminathan; S. L. Kochhar (2019). Major Flowering Trees of Tropical Gardens. Cambridge University Press. pp. 39–40. ISBN 978-1-108-48195-3. Retrieved 7 September 2021.

- ^ "Sal Tree". ecoindia.com. Retrieved 24 November 2020.

- ^ "Shorea robusta C.F.Gaertn. | Plants of the World Online | Kew Science". Plants of the World Online. Retrieved 2022-08-16.

- ^ Sahni, A.; Patnaik, R. (2022-06-01). "An Eocene Greenhouse Forested India: Were Biotic Radiations Triggered by Early Palaeogene Thermal Events?". Journal of the Geological Society of India. 98 (6): 753–759. Bibcode:2022JGSI...98..753S. doi:10.1007/s12594-022-2064-4. ISSN 0974-6889. S2CID 249536528.

- ^ "Shorea robusta in Flora of China @ efloras.org". www.efloras.org. Retrieved 2022-08-09.

- ^ "InfoChange India News & Features development news India - A rakhi for trees". Archived from the original on 2011-05-27.

- ^ http://bjmirror0112.wordpress.com/ [user-generated source]

- ^ List of Indian state trees

- ^ Oudhia P., Ganguali R. N. (1998). Is Lantana camara responsible for Sal-borer infestation in M.P.?. Insect Environment. 4 (1): 5.

- ^ a b Krishna, Nanditha; Amirthalingam, M (2014). Sacred plants of India. India Penguin. p. 487.

- ^ Porteous, Alexander (2012-04-03). The Forest in Folklore and Mythology. Courier Corporation. ISBN 978-0-486-12032-4.

- ^ Buddhistische Bilderwelt: Hans Wolfgang Schumann, Ein ikonographisches Handbuch des Mahayana- und Tantrayana-Buddhismus. Eugen Diederichs Verlag. Cologne. ISBN 3-424-00897-4, ISBN 978-3-424-00897-5

- ^ Eckard Schleberger, Die indische Götterwelt. Gestalt, Ausdruck und Sinnbild Eugen Diederich Verlag. Cologne. ISBN 3-424-00898-2, ISBN 978-3-424-00898-2

- ^ Buswell, Robert Jr; Lopez, Donald S. Jr., eds. (2013). Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. p. 724. ISBN 978-0-691-15786-3.

- ^ a b c Bhikkhu Nyanatusita, "What is the Real Sal Tree", Buddhist Publication Society Newsletter, No. 63, 2010, accessed on 15.1.2017 at https://www.scribd.com/document/192654045/Nyanatusita-Bhikkhu-What-is-the-Real-Sal-Tree

- ^ "Maha-parinibbana Sutta: The Great Discourse on the Total Unbinding" (DN 16), translated from the Pali by Thanissaro Bhikkhu". Retrieved 2015-06-29.

- ^ Chapter 1.1, Helen Craig McCullough's translation

- ^ L.B.Senaratne "The revered 'Sal Tree' and the real Sal Tree", Sunday Times, Sunday September 16, 2007, Accessed cessed on 15.1.2017 at http://www.sundaytimes.lk/070916/News/news00026.html

- ^ "Sal tree at Royal Palace Silver Pagoda", accessed on 17.1.2017 at https://samilux.wordpress.com/2009/09/20/sal-tree-at-royal-palace-silver-pagoda/ Archived 2017-01-18 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Weise, Kai. "Managing the Sacred Garden of Lumbini", in Asian Heritage Management: Contexts, Concerns, and Prospects, Routledge, 2013, p. 122.

- ^ a b Panda, H. (2011). Spirit Varnishes Technology Handbook (with Testing and Analysis). Delhi, India: Asia Pacific Business Press. pp. 226, 229–230.

- ^ Sala, Asvakarna[permanent dead link]