Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

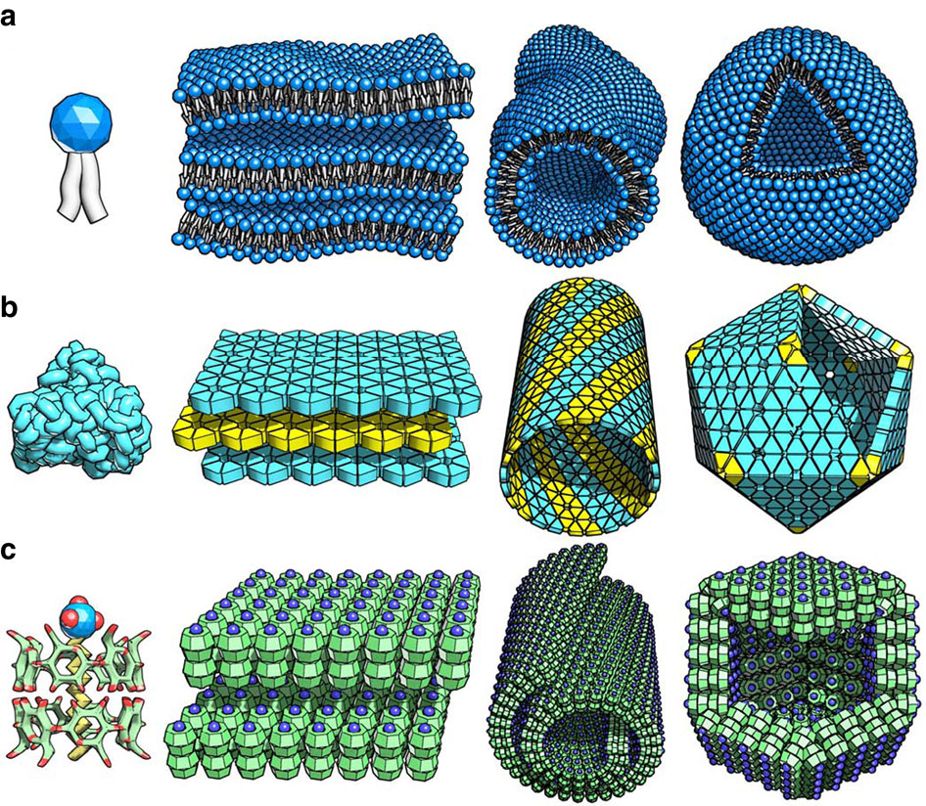

Self-assembly

View on Wikipedia

Self-assembly is a process in which a disordered system of pre-existing components forms an organized structure or pattern as a consequence of specific, local interactions among the components themselves, without external direction. When the constitutive components are molecules, the process is termed molecular self-assembly.

Self-assembly can be classified as either static or dynamic. In static self-assembly, the ordered state forms as a system approaches equilibrium, reducing its free energy. However, in dynamic self-assembly, patterns of pre-existing components organized by specific local interactions are not commonly described as "self-assembled" by scientists in the associated disciplines. These structures are better described as "self-organized", although these terms are often used interchangeably.

In chemistry and materials science

[edit]

Self-assembly in the classic sense can be defined as the spontaneous and reversible organization of molecular units into ordered structures by non-covalent interactions. The first property of a self-assembled system that this definition suggests is the spontaneity of the self-assembly process: the interactions responsible for the formation of the self-assembled system act on a strictly local level—in other words, the nanostructure builds itself.

Although self-assembly typically occurs between weakly-interacting species, this organization may be transferred into strongly-bound covalent systems. An example for this may be observed in the self-assembly of polyoxometalates. Evidence suggests that such molecules assemble via a dense-phase type mechanism whereby small oxometalate ions first assemble non-covalently in solution, followed by a condensation reaction that covalently binds the assembled units.[4] This process can be aided by the introduction of templating agents to control the formed species.[5] In such a way, highly organized covalent molecules may be formed in a specific manner.

Self-assembled nano-structure is an object that appears as a result of ordering and aggregation of individual nano-scale objects guided by some physical principle.

A particularly counter-intuitive example of a physical principle that can drive self-assembly is entropy maximization. Though entropy is conventionally associated with disorder, under suitable conditions [6] entropy can drive nano-scale objects to self-assemble into target structures in a controllable way.[7]

Another important class of self-assembly is field-directed assembly. An example of this is the phenomenon of electrostatic trapping. In this case an electric field is applied between two metallic nano-electrodes. The particles present in the environment are polarized by the applied electric field. Because of dipole interaction with the electric field gradient the particles are attracted to the gap between the electrodes.[8] Generalizations of this type approach involving different types of fields, e.g., using magnetic fields, using capillary interactions for particles trapped at interfaces, elastic interactions for particles suspended in liquid crystals have also been reported.

Regardless of the mechanism driving self-assembly, people take self-assembly approaches to materials synthesis to avoid the problem of having to construct materials one building block at a time. Avoiding one-at-a-time approaches is important because the amount of time required to place building blocks into a target structure is prohibitively difficult for structures that have macroscopic size.

Once materials of macroscopic size can be self-assembled, those materials can find use in many applications. For example, nano-structures such as nano-vacuum gaps are used for storing energy[9] and nuclear energy conversion.[10] Self-assembled tunable materials are promising candidates for large surface area electrodes in batteries and organic photovoltaic cells, as well as for microfluidic sensors and filters.[11]

Distinctive features

[edit]At this point, one may argue that any chemical reaction driving atoms and molecules to assemble into larger structures, such as precipitation, could fall into the category of self-assembly. However, there are at least three distinctive features that make self-assembly a distinct concept.

Order

[edit]First, the self-assembled structure must have a higher order than the isolated components, be it a shape or a particular task that the self-assembled entity may perform. This is generally not true in chemical reactions, where an ordered state may proceed towards a disordered state depending on thermodynamic parameters.

Interactions

[edit]The second important aspect of self-assembly is the predominant role of weak interactions (e.g. Van der Waals, capillary, , hydrogen bonds, or entropic forces) compared to more "traditional" covalent, ionic, or metallic bonds. These weak interactions are important in materials synthesis for two reasons.

First, weak interactions take a prominent place in materials, especially in biological systems. For instance, they determine the physical properties of liquids, the solubility of solids, and the organization of molecules in biological membranes.[12]

Second, in addition to the strength of the interactions, interactions with varying degrees of specificity can control self-assembly. Self-assembly that is mediated by DNA pairing interactions constitutes the interactions of the highest specificity that have been used to drive self-assembly.[13] At the other extreme, the least specific interactions are possibly those provided by emergent forces that arise from entropy maximization.[6]

Building blocks

[edit]The third distinctive feature of self-assembly is that the building blocks are not only atoms and molecules, but span a wide range of nano- and mesoscopic structures, with different chemical compositions, functionalities,[14] and shapes.[15] [16] Research into possible three-dimensional shapes of self-assembling micrites examines Platonic solids (regular polyhedral). The term 'micrite' was created by DARPA to refer to sub-millimeter sized microrobots, whose self-organizing abilities may be compared with those of slime mold.[17][18] Recent examples of novel building blocks include polyhedra and patchy particles.[14] Examples also included microparticles with complex geometries, such as hemispherical,[19] dimer,[20] discs,[21] rods, molecules, as well as multimers. These nanoscale building blocks can in turn be synthesized through conventional chemical routes or by other self-assembly strategies such as directional entropic forces. More recently, inverse design approaches have appeared where it is possible to fix a target self-assembled behavior, and determine an appropriate building block that will realize that behavior.[7]

Thermodynamics and kinetics

[edit]Self-assembly in microscopic systems usually starts from diffusion, followed by the nucleation of seeds, subsequent growth of the seeds, and ends at Ostwald ripening. The thermodynamic driving free energy can be either enthalpic or entropic or both.[6] In either the enthalpic or entropic case, self-assembly proceeds through the formation and breaking of bonds,[22] possibly with non-traditional forms of mediation. The kinetics of the self-assembly process is usually related to diffusion, for which the absorption/adsorption rate often follows a Langmuir adsorption model which in the diffusion controlled concentration (relatively diluted solution) can be estimated by the Fick's laws of diffusion. The desorption rate is determined by the bond strength of the surface molecules/atoms with a thermal activation energy barrier. The growth rate is the competition between these two processes.

Examples

[edit]Important examples of self-assembly in materials science include the formation of molecular crystals, colloids, lipid bilayers, phase-separated polymers, and self-assembled monolayers.[23][24] The folding of polypeptide chains into proteins and the folding of nucleic acids into their functional forms are examples of self-assembled biological structures. Recently, the three-dimensional macroporous structure was prepared via self-assembly of diphenylalanine derivative under cryoconditions, the obtained material can find the application in the field of regenerative medicine or drug delivery system.[25] P. Chen et al. demonstrated a microscale self-assembly method using the air-liquid interface established by Faraday wave as a template. This self-assembly method can be used for generation of diverse sets of symmetrical and periodic patterns from microscale materials such as hydrogels, cells, and cell spheroids.[26] Yasuga et al. demonstrated how fluid interfacial energy drives the emergence of three-dimensional periodic structures in micropillar scaffolds.[27] Myllymäki et al. demonstrated the formation of micelles, that undergo a change in morphology to fibers and eventually to spheres, all controlled by solvent change.[28]

Properties

[edit]Self-assembly extends the scope of chemistry aiming at synthesizing products with order and functionality properties, extending chemical bonds to weak interactions and encompassing the self-assembly of nanoscale building blocks at all length scales.[29] In covalent synthesis and polymerization, the scientist links atoms together in any desired conformation, which does not necessarily have to be the energetically most favoured position; self-assembling molecules, on the other hand, adopt a structure at the thermodynamic minimum, finding the best combination of interactions between subunits but not forming covalent bonds between them. In self-assembling structures, the scientist must predict this minimum, not merely place the atoms in the location desired.

Another characteristic common to nearly all self-assembled systems is their thermodynamic stability. For self-assembly to take place without intervention of external forces, the process must lead to a lower Gibbs free energy, thus self-assembled structures are thermodynamically more stable than the single, unassembled components. A direct consequence is the general tendency of self-assembled structures to be relatively free of defects. An example is the formation of two-dimensional superlattices composed of an orderly arrangement of micrometre-sized polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) spheres, starting from a solution containing the microspheres, in which the solvent is allowed to evaporate slowly in suitable conditions. In this case, the driving force is capillary interaction, which originates from the deformation of the surface of a liquid caused by the presence of floating or submerged particles.[30]

These two properties—weak interactions and thermodynamic stability—can be recalled to rationalise another property often found in self-assembled systems: the sensitivity to perturbations exerted by the external environment. These are small fluctuations that alter thermodynamic variables that might lead to marked changes in the structure and even compromise it, either during or after self-assembly. The weak nature of interactions is responsible for the flexibility of the architecture and allows for rearrangements of the structure in the direction determined by thermodynamics. If fluctuations bring the thermodynamic variables back to the starting condition, the structure is likely to go back to its initial configuration. This leads us to identify one more property of self-assembly, which is generally not observed in materials synthesized by other techniques: reversibility.

Self-assembly is a process which is easily influenced by external parameters. This feature can make synthesis rather complex because of the need to control many free parameters. Yet self-assembly has the advantage that a large variety of shapes and functions on many length scales can be obtained.[31]

The fundamental condition needed for nanoscale building blocks to self-assemble into an ordered structure is the simultaneous presence of long-range repulsive and short-range attractive forces.[32]

By choosing precursors with suitable physicochemical properties, it is possible to exert a fine control on the formation processes that produce complex structures. Clearly, the most important tool when it comes to designing a synthesis strategy for a material, is the knowledge of the chemistry of the building units. For example, it was demonstrated that it was possible to use diblock copolymers with different block reactivities in order to selectively embed maghemite nanoparticles and generate periodic materials with potential use as waveguides.[33]

In 2008 it was proposed that every self-assembly process presents a co-assembly, which makes the former term a misnomer. This thesis is built on the concept of mutual ordering of the self-assembling system and its environment.[34]

At the macroscopic scale

[edit]The most common examples of self-assembly at the macroscopic scale can be seen at interfaces between gases and liquids, where molecules can be confined at the nanoscale in the vertical direction and spread over long distances laterally. Examples of self-assembly at gas-liquid interfaces include breath-figures, self-assembled monolayers, droplet clusters, and Langmuir–Blodgett films, while crystallization of fullerene whiskers is an example of macroscopic self-assembly in between two liquids.[35][36] Another remarkable example of macroscopic self-assembly is the formation of thin quasicrystals at an air-liquid interface, which can be built up not only by inorganic, but also by organic molecular units.[37][38] Furthermore, it was reported that Fmoc protected L-DOPA amino acid (Fmoc-DOPA)[39][40] can present a minimal supramolecular polymer model, displaying a spontaneous structural transition from meta-stable spheres to fibrillar assemblies to gel-like material and finally to single crystals.[41]

Self-assembly processes can also be observed in systems of macroscopic building blocks. These building blocks can be externally propelled[42] or self-propelled.[43] Since the 1950s, scientists have built self-assembly systems exhibiting centimeter-sized components ranging from passive mechanical parts to mobile robots.[44] For systems at this scale, the component design can be precisely controlled. For some systems, the components' interaction preferences are programmable. The self-assembly processes can be easily monitored and analyzed by the components themselves or by external observers.[45]

In April 2014, a 3D printed plastic was combined with a "smart material" that self-assembles in water,[46] resulting in "4D printing".[47]

Consistent concepts of self-organization and self-assembly

[edit]People regularly use the terms "self-organization" and "self-assembly" interchangeably. As complex system science becomes more popular though, there is a higher need to clearly distinguish the differences between the two mechanisms to understand their significance in physical and biological systems. Both processes explain how collective order develops from "dynamic small-scale interactions".[48] Self-organization is a non-equilibrium process where self-assembly is a spontaneous process that leads toward equilibrium. Self-assembly requires components to remain essentially unchanged throughout the process. Besides the thermodynamic difference between the two, there is also a difference in formation. The first difference is what "encodes the global order of the whole" in self-assembly whereas in self-organization this initial encoding is not necessary. Another slight contrast refers to the minimum number of units needed to make an order. Self-organization appears to have a minimum number of units whereas self-assembly does not. The concepts may have particular application in connection with natural selection.[49] Eventually, these patterns may form one theory of pattern formation in nature.[50]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Wetterskog E, Agthe M, Mayence A, Grins J, Wang D, Rana S, et al. (October 2014). "Precise control over shape and size of iron oxide nanocrystals suitable for assembly into ordered particle arrays". Science and Technology of Advanced Materials. 15 (5) 055010. Bibcode:2014STAdM..15e5010W. doi:10.1088/1468-6996/15/5/055010. PMC 5099683. PMID 27877722.

- ^ Pham TA, Song F, Nguyen MT, Stöhr M (November 2014). "Self-assembly of pyrene derivatives on Au(111): substituent effects on intermolecular interactions". Chemical Communications. 50 (91): 14089–92. doi:10.1039/C4CC02753A. PMID 24905327.

- ^ Kling F (2016). Diffusion and structure formation of molecules on calcite(104) (PhD). Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz. doi:10.25358/openscience-2179.

- ^ Schreiber RE, Avram L, Neumann R (January 2018). "Self-Assembly through Noncovalent Preorganization of Reactants: Explaining the Formation of a Polyfluoroxometalate". Chemistry: A European Journal. 24 (2): 369–379. doi:10.1002/chem.201704287. PMID 29064591.

- ^ Miras HN, Cooper GJ, Long DL, Bögge H, Müller A, Streb C, Cronin L (January 2010). "Unveiling the transient template in the self-assembly of a molecular oxide nanowheel". Science. 327 (5961): 72–4. Bibcode:2010Sci...327...72M. doi:10.1126/science.1181735. PMID 20044572. S2CID 24736211.

- ^ a b c van Anders G, Klotsa D, Ahmed NK, Engel M, Glotzer SC (November 2014). "Understanding shape entropy through local dense packing". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 111 (45): E4812-21. arXiv:1309.1187. Bibcode:2014PNAS..111E4812V. doi:10.1073/pnas.1418159111. PMC 4234574. PMID 25344532.

- ^ a b Geng Y, van Anders G, Dodd PM, Dshemuchadse J, Glotzer SC (July 2019). "Engineering entropy for the inverse design of colloidal crystals from hard shapes". Science Advances. 5 (7) eaaw0514. arXiv:1712.02471. Bibcode:2019SciA....5..514G. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aaw0514. PMC 6611692. PMID 31281885.

- ^ Bezryadin A, Westervelt RM, Tinkham M (1999). "Self-assembled chains of graphitized carbon nanoparticles". Applied Physics Letters. 74 (18): 2699–2701. arXiv:cond-mat/9810235. Bibcode:1999ApPhL..74.2699B. doi:10.1063/1.123941. S2CID 14398155.

- ^ Lyon D, Hubler A (2013). "Gap size dependence of the dielectric strength in nano vacuum gaps". IEEE Transactions on Dielectrics and Electrical Insulation. 20 (4): 1467–1471. doi:10.1109/TDEI.2013.6571470. S2CID 709782.

- ^ Shinn E (2012). "Nuclear energy conversion with stacks of graphene nanocapacitors". Complexity. 18 (3): 24–27. Bibcode:2013Cmplx..18c..24S. doi:10.1002/cplx.21427.

- ^ Demortière A, Snezhko A, Sapozhnikov MV, Becker N, Proslier T, Aranson IS (2014). "Self-assembled tunable networks of sticky colloidal particles". Nature Communications. 5: 3117. Bibcode:2014NatCo...5.3117D. doi:10.1038/ncomms4117. PMID 24445324.

- ^ Israelachvili JN (2011). Intermolecular and Surface Forces (3rd ed.). Elsevier.

- ^ Jones MR, Seeman NC, Mirkin CA (February 2015). "Nanomaterials. Programmable materials and the nature of the DNA bond". Science. 347 (6224) 1260901. doi:10.1126/science.1260901. PMID 25700524.

- ^ a b Glotzer SC, Solomon MJ (August 2007). "Anisotropy of building blocks and their assembly into complex structures". Nature Materials. 6 (8): 557–62. Bibcode:2007NatMa...6..557G. doi:10.1038/nmat1949. PMID 17667968.

- ^ van Anders G, Ahmed NK, Smith R, Engel M, Glotzer SC (January 2014). "Entropically patchy particles: engineering valence through shape entropy". ACS Nano. 8 (1): 931–40. arXiv:1304.7545. doi:10.1021/nn4057353. PMID 24359081. S2CID 9669569.

- ^ Mayorga, Luis S.; Masone, Diego (2024). "The Secret Ballet Inside Multivesicular Bodies". ACS Nano. 18 (24): 15651–15660. doi:10.1021/acsnano.4c01590. PMID 38830824.

- ^ Solem JC (2002). "Self-assembling micrites based on the Platonic solids". Robotics and Autonomous Systems. 38 (2): 69–92. doi:10.1016/s0921-8890(01)00167-1.

- ^ Trewhella J, Solem JC (1998). "Future Research Directions for Los Alamos: A Perspective from the Los Alamos Fellows" (PDF). Los Alamos National Laboratory Report LA-UR-02-7722: 9.

- ^ Hosein ID, Liddell CM (August 2007). "Convectively assembled nonspherical mushroom cap-based colloidal crystals". Langmuir. 23 (17): 8810–4. doi:10.1021/la700865t. PMID 17630788.

- ^ Hosein ID, Liddell CM (October 2007). "Convectively assembled asymmetric dimer-based colloidal crystals". Langmuir. 23 (21): 10479–85. doi:10.1021/la7007254. PMID 17629310.

- ^ Lee JA, Meng L, Norris DJ, Scriven LE, Tsapatsis M (June 2006). "Colloidal crystal layers of hexagonal nanoplates by convective assembly". Langmuir. 22 (12): 5217–9. doi:10.1021/la0601206. PMID 16732640.

- ^ Harper ES, van Anders G, Glotzer SC (August 2019). "The entropic bond in colloidal crystals". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 116 (34): 16703–16710. Bibcode:2019PNAS..11616703H. doi:10.1073/pnas.1822092116. PMC 6708323. PMID 31375631.

- ^ Whitesides GM, Boncheva M (April 2002). "Beyond molecules: self-assembly of mesoscopic and macroscopic components". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 99 (8): 4769–74. Bibcode:2002PNAS...99.4769W. doi:10.1073/pnas.082065899. PMC 122665. PMID 11959929.

- ^ Whitesides GM, Kriebel JK, Love JC (2005). "Molecular engineering of surfaces using self-assembled monolayers" (PDF). Science Progress. 88 (Pt 1): 17–48. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.668.2591. doi:10.3184/003685005783238462. PMC 10367539. PMID 16372593. S2CID 46367976. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-06-20. Retrieved 2016-12-21.

- ^ Berillo D, Mattiasson B, Galaev IY, Kirsebom H (February 2012). "Formation of macroporous self-assembled hydrogels through cryogelation of Fmoc-Phe-Phe". Journal of Colloid and Interface Science. 368 (1): 226–30. Bibcode:2012JCIS..368..226B. doi:10.1016/j.jcis.2011.11.006. PMID 22129632.

- ^ Chen P, Luo Z, Güven S, Tasoglu S, Ganesan AV, Weng A, Demirci U (September 2014). "Microscale assembly directed by liquid-based template". Advanced Materials. 26 (34): 5936–41. Bibcode:2014AdM....26.5936C. doi:10.1002/adma.201402079. PMC 4159433. PMID 24956442.

- ^ Yasuga, Hiroki; Iseri, Emre; Wei, Xi; Kaya, Kerem; Di Dio, Giacomo; Osaki, Toshihisa; Kamiya, Koki; Nikolakopoulou, Polyxeni; Buchmann, Sebastian; Sundin, Johan; Bagheri, Shervin; Takeuchi, Shoji; Herland, Anna; Miki, Norihisa; van der Wijngaart, Wouter (2021). "Fluid interfacial energy drives the emergence of three-dimensional periodic structures in micropillar scaffolds". Nature Physics. 17 (7): 794–800. Bibcode:2021NatPh..17..794Y. doi:10.1038/s41567-021-01204-4. ISSN 1745-2473. S2CID 233702358.

- ^ Myllymäki TT, Yang H, Liljeström V, Kostiainen MA, Malho JM, Zhu XX, Ikkala O (September 2016). "Hydrogen bonding asymmetric star-shape derivative of bile acid leads to supramolecular fibrillar aggregates that wrap into micrometer spheres". Soft Matter. 12 (34): 7159–65. Bibcode:2016SMat...12.7159M. doi:10.1039/C6SM01329E. PMC 5322467. PMID 27491728.

- ^ Ozin GA, Arsenault AC (2005). Nanochemistry: a chemical approach to nanomaterials. Cambridge: Royal Society of Chemistry. ISBN 978-0-85404-664-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: publisher location (link) - ^ Velev OD, Denkov ND, Kralchevsky PA, Ivanov IB, Yoshimura H, Nagayama K (1992). "Mechanism of formation of two-dimensional crystals from latex particles on substrates". Langmuir. 8 (12): 3183–3190. doi:10.1021/la00048a054.

- ^ Lehn JM (March 2002). "Toward self-organization and complex matter". Science. 295 (5564): 2400–3. Bibcode:2002Sci...295.2400L. doi:10.1126/science.1071063. PMID 11923524. S2CID 37836839.

- ^ Forster PM, Cheetham AK (2002). "Open-Framework Nickel Succinate, [Ni7(C4H4O4)6(OH)2(H2O)2]⋅2H2O: A New Hybrid Material with Three-Dimensional Ni−O−Ni Connectivity". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 41 (3): 457–459. doi:10.1002/1521-3773(20020201)41:3<457::AID-ANIE457>3.0.CO;2-W. PMID 12491377.

- ^ Gazit O, Khalfin R, Cohen Y, Tannenbaum R (2009). "Self-Assembled Diblock Copolymer "Nanoreactors" as "Catalysts" for Metal Nanoparticle Synthesis". The Journal of Physical Chemistry C. 113 (2): 576–583. doi:10.1021/jp807668h.

- ^ Uskoković V (September 2008). "Isn't self-assembly a misnomer? Multi-disciplinary arguments in favor of co-assembly". Advances in Colloid and Interface Science. 141 (1–2): 37–47. doi:10.1016/j.cis.2008.02.004. PMID 18406396.

- ^ Ariga K, Hill JP, Lee MV, Vinu A, Charvet R, Acharya S (January 2008). "Challenges and breakthroughs in recent research on self-assembly". Science and Technology of Advanced Materials. 9 (1) 014109. Bibcode:2008STAdM...9a4109A. doi:10.1088/1468-6996/9/1/014109. PMC 5099804. PMID 27877935.

- ^ Ariga K, Nishikawa M, Mori T, Takeya J, Shrestha LK, Hill JP (2019). "Self-assembly as a key player for materials nanoarchitectonics". Science and Technology of Advanced Materials. 20 (1): 51–95. Bibcode:2019STAdM..20...51A. doi:10.1080/14686996.2018.1553108. PMC 6374972. PMID 30787960.

- ^ Talapin DV, Shevchenko EV, Bodnarchuk MI, Ye X, Chen J, Murray CB (October 2009). "Quasicrystalline order in self-assembled binary nanoparticle superlattices". Nature. 461 (7266): 964–7. Bibcode:2009Natur.461..964T. doi:10.1038/nature08439. PMID 19829378. S2CID 4344953.

- ^ Nagaoka Y, Zhu H, Eggert D, Chen O (December 2018). "Single-component quasicrystalline nanocrystal superlattices through flexible polygon tiling rule". Science. 362 (6421): 1396–1400. Bibcode:2018Sci...362.1396N. doi:10.1126/science.aav0790. hdl:21.11116/0000-0002-B8DF-4. PMID 30573624.

- ^ Saha, Abhijit; Bolisetty, Sreenath; Handschin, Stephan; Mezzenga, Raffaele (2013). "Self-assembly and fibrillization of a Fmoc-functionalized polyphenolic amino acid". Soft Matter. 9 (43): 10239. Bibcode:2013SMat....910239S. doi:10.1039/c3sm52222a. ISSN 1744-683X.

- ^ Fichman, Galit; Guterman, Tom; Adler-Abramovich, Lihi; Gazit, Ehud (2015). "Synergetic functional properties of two-component single amino acid-based hydrogels". CrystEngComm. 17 (42): 8105–8112. Bibcode:2015CEG....17.8105F. doi:10.1039/C5CE01051A. ISSN 1466-8033.

- ^ Fichman, Galit; Guterman, Tom; Damron, Joshua; Adler-Abramovich, Lihi; Schmidt, Judith; Kesselman, Ellina; Shimon, Linda J. W.; Ramamoorthy, Ayyalusamy; Talmon, Yeshayahu; Gazit, Ehud (2016-02-05). "Spontaneous structural transition and crystal formation in minimal supramolecular polymer model". Science Advances. 2 (2) e1500827. Bibcode:2016SciA....2E0827F. doi:10.1126/sciadv.1500827. ISSN 2375-2548. PMC 4758747. PMID 26933679.

- ^ Hosokawa K, Shimoyama I, Miura H (1994). "Dynamics of self-assembling systems: Analogy with chemical kinetics". Artificial Life. 1 (4): 413–427. doi:10.1162/artl.1994.1.413.

- ^ Groß R, Bonani M, Mondada F, Dorigo M (2006). "Autonomous self-assembly in swarm-bots". IEEE Transactions on Robotics. 22 (6): 1115–1130. doi:10.1109/TRO.2006.882919. S2CID 606998.

- ^ Groß R, Dorigo M (2008). "Self-assembly at the macroscopic scale". Proceedings of the IEEE. 96 (9): 1490–1508. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.145.8984. doi:10.1109/JPROC.2008.927352. S2CID 7094751. Archived from the original on Nov 18, 2023.

- ^ Stephenson C, Lyon D, Hübler A (February 2017). "Topological properties of a self-assembled electrical network via ab initio calculation". Scientific Reports. 7 41621. Bibcode:2017NatSR...741621S. doi:10.1038/srep41621. PMC 5290745. PMID 28155863.

- ^ D'Monte, Leslie (7 May 2014). "Indian market sees promise in 3D printers". Mint.

- ^ Tibbits, Skylar (February 2013). "The emergence of "4D printing"". TED Talk. Archived from the original on Nov 26, 2021.

- ^ Halley JD, Winkler DA (2008). "Consistent Concepts of Self-organization and Self-assembly". Complexity. 14 (2): 10–17. Bibcode:2008Cmplx..14b..10H. doi:10.1002/cplx.20235.

- ^

Halley JD, Winkler DA (May 2008). "Critical-like self-organization and natural selection: two facets of a single evolutionary process?". Bio Systems. 92 (2): 148–58. Bibcode:2008BiSys..92..148H. doi:10.1016/j.biosystems.2008.01.005. PMID 18353531.

We argue that critical-like dynamics self-organize relatively easily in non-equilibrium systems, and that in biological systems such dynamics serve as templates upon which natural selection builds further elaborations. These critical-like states can be modified by natural selection in two fundamental ways, reflecting the selective advantage (if any) of heritable variations either among avalanche participants or among whole systems.

- ^

Halley JD, Winkler DA (2008). "Consistent Concepts of Self-organization and Self-assembly". Complexity. 14 (2): 15. Bibcode:2008Cmplx..14b..10H. doi:10.1002/cplx.20235.

[...] it may one day even be possible to integrate these pattern forming mechanisms into the one general theory of pattern formation in nature.

Further reading

[edit]- Whitesides GM, Grzybowski B (March 2002). "Self-assembly at all scales". Science. 295 (5564): 2418–21. Bibcode:2002Sci...295.2418W. doi:10.1126/science.1070821. PMID 11923529. S2CID 40684317.

- Damasceno PF, Engel M, Glotzer SC (July 2012). "Predictive self-assembly of polyhedra into complex structures". Science. 337 (6093): 453–7. Bibcode:2012Sci...337..453D. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.455.6962. doi:10.1126/science.1220869. PMID 22837525. S2CID 7177740.

- Rothemund PW, Papadakis N, Winfree E (December 2004). "Algorithmic self-assembly of DNA Sierpinski triangles". PLOS Biology. 2 (12) e424. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0020424. PMC 534809. PMID 15583715.

- Stephens AD (1977). "The management of cystinuria in 1976". Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine. 70 Suppl 3 (3_suppl): 24–6. doi:10.1177/00359157770700S310. PMC 1543588. PMID 122665.

External links

[edit]- Kuniaki Nagayama, Freeview Video 'Self-Assembly: Nature's Way To Do It, A Royal Institution Lecture by the Vega Science Trust.

- Paper Molecular Self-Assembly

- Wiki: C2 Self Assembly from a computer programming perspective.

- Pelesko, J.A., (2007) Self Assembly: The Science of Things That Put Themselves Together, Chapman & Hall/CRC Press.

- A brief page on self-assembly at the University of Delaware Self Assembly

- Structure and Dynamics of Organic Nanostructures Archived 2016-04-21 at the Wayback Machine

- Metal organic coordination networks of oligopyridines and Cu on graphite Archived 2016-06-11 at the Wayback Machine