Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Adamantane

View on Wikipedia

| |||

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

Adamantane[1] | |||

| Systematic IUPAC name

Tricyclo[3.3.1.13,7]decane[2] | |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol)

|

|||

| 1901173 | |||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChEMBL | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| DrugBank | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.005.457 | ||

| EC Number |

| ||

| 26963 | |||

PubChem CID

|

|||

| UNII | |||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| C10H16 | |||

| Molar mass | 136.238 g·mol−1 | ||

| Appearance | White to off-white powder | ||

| Density | 1.07 g/cm3 (25 °C)[2] | ||

| Melting point | 270 °C (518 °F; 543 K)[2] | ||

| Boiling point | Sublimes[2] | ||

| Poorly soluble | |||

| Solubility in other solvents | Soluble in hydrocarbons | ||

Refractive index (nD)

|

1.568[2][3] | ||

| Structure | |||

| cubic, space group Fm3m | |||

| 4 | |||

| 0 D | |||

| Hazards | |||

| Occupational safety and health (OHS/OSH): | |||

Main hazards

|

Flammable | ||

| GHS labelling: | |||

| |||

| Warning | |||

| H319, H400 | |||

| P264, P273, P280, P305+P351+P338, P337+P313, P391, P501 | |||

| Related compounds | |||

Related compounds:

|

Memantine Rimantadine Amantadine | ||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |||

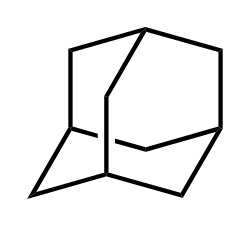

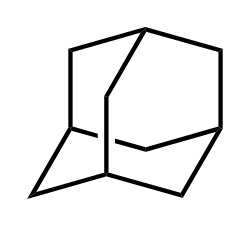

Adamantane is an organic compound with formula C10H16 or, more descriptively, (CH)4(CH2)6. Adamantane molecules can be described as the fusion of three cyclohexane rings. The molecule is both rigid and virtually stress-free. Adamantane is the most stable isomer of C10H16. The spatial arrangement of carbon atoms in the adamantane molecule is the same as in the diamond crystal. This similarity led to the name adamantane, which is derived from the Greek adamantinos (relating to steel or diamond).[4] It is a white solid with a camphor-like odor. It is the simplest diamondoid.

The discovery of adamantane in petroleum in 1933 launched a new field of chemistry dedicated to the synthesis and properties of polyhedral organic compounds. Adamantane derivatives have found practical application as drugs, polymeric materials, and thermally stable lubricants.

History and synthesis

[edit]In 1924, H. Decker suggested the existence of adamantane, which he called decaterpene.[5]

The first attempted laboratory synthesis was made in 1924 by German chemist Hans Meerwein using the reaction of formaldehyde with diethyl malonate in the presence of piperidine. Instead of adamantane, Meerwein obtained 1,3,5,7-tetracarbomethoxybicyclo[3.3.1]nonane-2,6-dione: this compound, later named Meerwein's ester, was used in the synthesis of adamantane and its derivatives.[6] D. Bottger tried to obtain adamantane using Meerwein's ester as precursor. The product, tricyclo-[3.3.1.13,7], was not adamantane, but a derivative.[7]

Other researchers attempted to synthesize adamantane using phloroglucinol and derivatives of cyclohexanone, but also failed.[8]

Adamantane was first synthesized by Vladimir Prelog in 1941 from Meerwein's ester.[9][10] With a yield of 0.16%, the five-stage process was impractical (simplified in the image below). The method is used to synthesize certain derivatives of adamantane.[8]

Prelog's method was refined in 1956. The decarboxylation yield was increased by the addition of the Hunsdiecker pathway (11%) and the Hoffman reaction (24%) that raised the total yield to 6.5%.[11][12] The process was still too complex, and a more convenient method was found in 1957 by Paul von Ragué Schleyer: dicyclopentadiene was first hydrogenated in the presence of a catalyst (e.g. platinum dioxide) to give tricyclodecane and then transformed into adamantane using a Lewis acid (e.g. aluminium chloride) as another catalyst. This method increased the yield to 30–40% and provided an affordable source of adamantane; it therefore stimulated characterization of adamantane and is still used in laboratory practice.[13][14] The adamantane synthesis yield was later increased to 60%[15] and 98% by ultrasound and superacid catalysis.[16] Today, adamantane is an affordable chemical compound with a cost of one or two USD per gram.

All the above methods yield adamantane as a polycrystalline powder. Using this powder, single crystals can be grown from the melt, solution, or vapor phase (e.g. with the Bridgman–Stockbarger technique). Melt growth results in the worst crystalline quality with a mosaic spread in the X-ray reflection of about 1°. The best crystals are obtained from the liquid phase, but the growth is impracticably slow – several months for a 5–10 mm crystal. Growth from the vapor phase is a reasonable compromise in terms of speed and quality.[17] Adamantane is sublimed in a quartz tube placed in a furnace, which is equipped with several heaters maintaining a certain temperature gradient (about 10 °C/cm for adamantane) along the tube. Crystallization starts at one end of the tube, which is kept near the freezing point of adamantane. Slow cooling of the tube, while maintaining the temperature gradient, gradually shifts the melting zone (rate ~2 mm/hour), producing a single-crystal boule.[18]

Natural occurrence

[edit]Adamantane was first isolated from petroleum by the Czech chemists S. Landa, V. Machacek, and M. Mzourek.[19][20] They used fractional distillation of petroleum. They could produce only a few milligrams of adamantane, but noticed its high boiling and melting points. Because of the (assumed) similarity of its structure to that of diamond, the new compound was named adamantane.[8]

Petroleum remains a source of adamantane; the content varies from between 0.0001% and 0.03% depending on the oil field and is too low for commercial production.[21][22]

Petroleum contains more than thirty derivatives of adamantane.[21] Their isolation from a complex mixture of hydrocarbons is possible due to their high melting point and the ability to distill with water vapor and form stable adducts with thiourea.

Physical properties

[edit]Pure adamantane is a colorless, crystalline solid with a characteristic camphor smell. It is practically insoluble in water, but readily soluble in nonpolar organic solvents.[23] Adamantane has an unusually high melting point for a hydrocarbon. At 270 °C, its melting point is much higher than other hydrocarbons with the same molecular weight, such as camphene (45 °C), limonene (−74 °C), ocimene (50 °C), terpinene (60 °C) or twistane (164 °C), or than a linear C10H22 hydrocarbon decane (−28 °C). However, adamantane slowly sublimes even at room temperature.[24] Adamantane can be distilled with water vapor.[22]

Structure

[edit]

As deduced by electron diffraction and X-ray crystallography, the molecule has Td symmetry. The carbon–carbon bond lengths are 1.54 Å, almost identical to that of diamond. The carbon–hydrogen distances are 1.112 Å.[3]

At ambient conditions, adamantane crystallizes in a face-centered cubic structure (space group Fm3m, a = 9.426 ± 0.008 Å, four molecules in the unit cell) containing orientationally disordered adamantane molecules. This structure transforms into an ordered, primitive, tetragonal phase (a = 6.641 Å, c = 8.875 Å) with two molecules per cell, either upon cooling to 208 K or pressurizing to above 0.5 GPa.[8][24]

This phase transition is of the first order; it is accompanied by an anomaly in the heat capacity, elastic, and other properties. In particular, whereas adamantane molecules freely rotate in the cubic phase, they are frozen in the tetragonal one; the density increases stepwise from 1.08 to 1.18 g/cm3, and the entropy changes by a significant amount of 1594 J/(mol·K).[17]

Hardness

[edit]Elastic constants of adamantane were measured using large (centimeter-sized) single crystals and the ultrasonic echo technique. The principal value of the elasticity tensor, C11, was deduced as 7.52, 8.20, and 6.17 GPa for the <110>, <111>, and <100> crystalline directions.[18] For comparison, the corresponding values for crystalline diamond are 1161, 1174, and 1123 GPa.[25] The arrangement of carbon atoms is the same in adamantane and diamond;[26] however, in the adamantane solid, molecules do not form a covalent lattice as in diamond, but interact through weak van der Waals forces. As a result, adamantane crystals are very soft and plastic.[17][18][27]

Spectroscopy

[edit]The nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectrum of adamantane consists of two poorly resolved signals, which correspond to sites 1 and 2 (see picture below). The 1H and 13C NMR chemical shifts are respectively 1.873 and 1.756 ppm and are 28.46 and 37.85 ppm.[28] The simplicity of these spectra is consistent with high molecular symmetry.

Mass spectra of adamantane and its derivatives are rather characteristic. The main peak at m/z = 136 corresponds to the C

10H+

16 ion. Its fragmentation results in weaker signals as m/z = 93, 80, 79, 67, 41 and 39.[3][28]

The infrared absorption spectrum of adamantane is relatively simple because of the high symmetry of the molecule. The main absorption bands and their assignment are given in the table:[3]

| Wavenumber, cm−1 | Assignment* |

|---|---|

| 444 | δ(CCC) |

| 638 | δ(CCC) |

| 798 | ν(C−C) |

| 970 | ρ(CH2), ν(C−C), δ(HCC) |

| 1103 | δ(HCC) |

| 1312 | ν(C−C), ω(CH2) |

| 1356 | δ(HCC), ω(CH2) |

| 1458 | δ(HCH) |

| 2850 | ν(C−H) in CH2 groups |

| 2910 | ν(C−H) in CH2 groups |

| 2930 | ν(C−H) in CH2 groups |

* Legends correspond to types of oscillations: δ – deformation, ν – stretching, ρ and ω – out of plane deformation vibrations of CH2 groups.

Optical activity

[edit]Adamantane derivatives with different substituents at every nodal carbon sites are chiral.[29] Such optical activity was described in adamantane in 1969 with the four different substituents being hydrogen, bromine, methyl, and carboxyl. The values of specific rotation are small and are usually within 1°.[30][31]

Nomenclature

[edit]Using the rules of systematic nomenclature, adamantane is called tricyclo[3.3.1.13,7]decane. However, IUPAC recommends using the name "adamantane".[1]

The adamantane molecule is composed of only carbon and hydrogen and has Td symmetry. Therefore, its 16 hydrogen and 10 carbon atoms can be described by only two sites, which are labeled in the figure as 1 (4 equivalent sites) and 2 (6 equivalent sites).

Structural relatives of adamantane are noradamantane and homoadamantane, which respectively contain one less and one more CH2 link than the adamantane.

The functional group derived from adamantane is adamantyl, formally named as 1-adamantyl or 2-adamantyl depending on which site is connected to the parent molecule. Adamantyl groups are a bulky pendant group used to improve the thermal and mechanical properties of polymers.[32][33]

Chemical properties

[edit]Adamantane cations

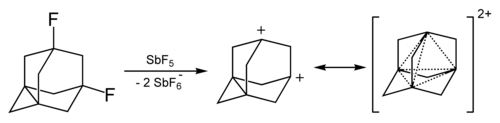

[edit]The adamantane cation can be produced by treating 1-fluoro-adamantane with SbF5. Its stability is relatively high.[34][35]

The dication of 1,3-didehydroadamantane was obtained in solutions of superacids. It also has elevated stability due to the phenomenon called "three-dimensional aromaticity"[36] or homoaromaticity.[37] This four-center two-electron bond involves one pair of electrons delocalized among the four bridgehead atoms.

Reactions

[edit]Most reactions of adamantane occur via the tertiary carbon sites. They are involved in the reaction of adamantane with concentrated sulfuric acid which produces adamantanone.[38]

The carbonyl group of adamantanone allows further reactions via the bridging site. For example, adamantanone is the starting compound for obtaining such derivatives of adamantane as 2-adamantanecarbonitrile[39] and 2-methyl-adamantane.[40]

Bromination

[edit]Adamantane readily reacts with various brominating agents, including molecular bromine. The composition and the ratio of the reaction products depend on the reaction conditions and especially the presence and type of catalysts.[21]

Boiling of adamantane with bromine results in a monosubstituted adamantane, 1-bromadamantane. Multiple substitution with bromine is achieved by adding a Lewis acid catalyst.[41]

The rate of bromination is accelerated upon addition of Lewis acids and is unchanged by irradiation or addition of free radicals. This indicates that the reaction occurs via an ionic mechanism.[8]

Fluorination

[edit]The first fluorinations of adamantane were conducted using 1-hydroxyadamantane[42] and 1-aminoadamantane as initial compounds. Later, fluorination was achieved starting from adamantane itself.[43] In all these cases, reaction proceeded via formation of the adamantane cation which then interacted with fluorinated nucleophiles. Fluorination of adamantane with gaseous fluorine has also been reported.[44]

Carboxylation

[edit]Carboxylation of adamantane with formic acid gives 1-adamantanecarboxylic acid.[45]

Oxidation

[edit]1-Hydroxyadamantane is readily formed by hydrolysis of 1-bromadamantane in aqueous solution of acetone. It can also be produced by ozonation of the adamantane:[46]

Others

[edit]Adamantane interacts with benzene in the presence of Lewis acids, resulting in a Friedel–Crafts reaction.[47] Aryl-substituted adamantane derivatives can be easily obtained starting from 1-hydroxyadamantane. In particular, the reaction with anisole proceeds under normal conditions and does not require a catalyst.[41]

Nitration of adamantane is a difficult reaction characterized by moderate yields.[48] A nitrogen-substituted drug amantadine can be prepared by reacting adamantane with bromine or nitric acid to give the bromide or nitroester at the 1-position. Reaction of either compound with acetonitrile affords the acetamide, which is hydrolyzed to give 1-adamantylamine:[49]

Uses

[edit]Adamantane itself enjoys few applications since it is merely an unfunctionalized hydrocarbon. It is used in some dry etching masks[50] and polymer formulations.

In solid-state NMR spectroscopy, adamantane is a common standard for chemical shift referencing.[51]

In dye lasers, adamantane may be used to extend the life of the gain medium; it cannot be photoionized under atmosphere because its absorption bands lie in the vacuum-ultraviolet region of the spectrum. Photoionization energies have been determined for adamantane as well as for several bigger diamondoids.[52]

In medicine

[edit]All medical applications known so far involve not pure adamantane, but its derivatives. The first adamantane derivative used as a drug was amantadine – first (1967) as an antiviral drug against various strains of influenza[53] and then to treat Parkinson's disease.[54][55] Other drugs among adamantane derivatives include adapalene, adapromine, bromantane (bromantan), carmantadine, chlodantane (chlodantan), dopamantine, gludantan (gludantane), hemantane (hymantane), idramantone (kemantane), memantine, nitromemantine rimantadine, saxagliptin, somantadine, tromantadine, and vildagliptin. Polymers of adamantane have been patented as antiviral agents against HIV.[56]

Influenza virus strains have developed drug resistance to amantadine and rimantadine, which are not effective against prevalent strains as of 2016.

In designer drugs

[edit]Adamantane was recently identified as a key structural subunit in several synthetic cannabinoid designer drugs, namely AB-001 and SDB-001.[57]

Spacecraft propellant

[edit]Adamantane is an attractive candidate for propellant in Hall-effect thrusters because it ionizes easily, can be stored in solid form rather than a heavy pressure tank, and is relatively nontoxic.[58]

Potential technological applications

[edit]Some alkyl derivatives of adamantane have been used as a working fluid in hydraulic systems.[59] Adamantane-based polymers might find application for coatings of touchscreens,[60] and there are prospects for using adamantane and its homologues in nanotechnology. For example, the soft cage-like structure of adamantane solid allows incorporation of guest molecules, which can be released inside the human body upon breaking the matrix.[15][61] Adamantane could be used as molecular building blocks for self-assembly of molecular crystals.[62][63]

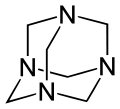

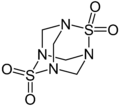

Adamantane analogues

[edit]Many molecules and ions adopt adamantane-like cage structures. Those include phosphorus trioxide P4O6, arsenic trioxide As4O6, phosphorus pentoxide P4O10 = (PO)4O6, phosphorus pentasulfide P4S10 = (PS)4S6, and hexamethylenetetramine C6N4H12 = N4(CH2)6.[64] Particularly notorious is tetramethylenedisulfotetramine, often shortened to "tetramine", a rodenticide banned in most countries for extreme toxicity to humans. The silicon analogue of adamantane, sila-adamantane, was synthesized in 2005.[65] Arsenicin A is a naturally occurring organoarsenic chemical isolated from the New Caledonian sea sponge Echinochalina bargibanti and is the first known heterocycle to contain multiple arsenic atoms.[66][67][68][69]

-

Adamantane

Conjoining adamantane cages produces higher diamondoids, such as diamantane (C14H20 – two fused adamantane cages), triamantane (C18H24), tetramantane (C22H28), pentamantane (C26H32), hexamantane (C26H30), etc. Their synthesis is similar to that of adamantane and like adamantane, they can also be extracted from petroleum, though at even much smaller yields.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Nomenclature of Organic Chemistry: IUPAC Recommendations and Preferred Names 2013 (Blue Book). Cambridge: The Royal Society of Chemistry. 2014. p. 169. doi:10.1039/9781849733069-FP001. ISBN 978-0-85404-182-4.

The retained names adamantane and cubane are used in general nomenclature and as preferred IUPAC names.

- ^ a b c d e Haynes, William M., ed. (2016). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (97th ed.). CRC Press. p. 3.524. ISBN 978-1-4987-5429-3.

- ^ a b c d Bagrii, E.I. (1989). Adamantanes: synthesis, properties, applications (in Russian). Nauka. pp. 5–57. ISBN 5-02-001382-X. Archived from the original on 2024-03-08. Retrieved 2016-09-23.

- ^ Alexander Senning. Elsevier's Dictionary of Chemoetymology. Elsevier, 2006, p. 6 ISBN 0-444-52239-5.

- ^ Decker H. (1924). "Versammlung deutscher Naturforscher und Ärzte. Innsbruck, 21–27 September 1924". Angew. Chem. 37 (41): 795. Bibcode:1924AngCh..37..781.. doi:10.1002/ange.19240374102.

- ^ Radcliffe MD, Gutierrez A, Blount JF, Mislow K (1984). "Structure of Meerwein's ester and of its benzene inclusion compound" (PDF). Journal of the American Chemical Society. 106 (3): 682–687. doi:10.1021/ja00315a037. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-08-09. Retrieved 2010-05-26.

- ^ Coffey, S. and Rodd, S. (eds.) (1969) Chemistry of Carbon Compounds. Vol 2. Part C. Elsevier Publishing: New York.

- ^ a b c d e Fort, Raymond C. Jr., Schleyers, Paul Von R. (1964). "Adamantane: Consequences of Diamondoid Structure". Chem. Rev. 64 (3): 277–300. doi:10.1021/cr60229a004.

- ^ Prelog V, Seiwerth R (1941). "Über die Synthese des Adamantans". Berichte. 74 (10): 1644–1648. doi:10.1002/cber.19410741004.

- ^ Prelog V, Seiwerth R (1941). "Über eine neue, ergiebigere Darstellung des Adamantans". Berichte. 74 (11): 1769–1772. doi:10.1002/cber.19410741109.

- ^ Stetter H, Bander O, Neumann W (1956). "Über Verbindungen mit Urotropin-Struktur, VIII. Mitteil.: Neue Wege der Adamantan-Synthese". Chem. Ber. (in German). 89 (8): 1922. doi:10.1002/cber.19560890820.

- ^ McKervey M (1980). "Synthetic approaches to large diamondoid hydrocarbons". Tetrahedron. 36 (8): 971–992. doi:10.1016/0040-4020(80)80050-0.

- ^ Schleyer, P. von R. (1957). "A Simple Preparation of Adamantane". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 79 (12): 3292. doi:10.1021/ja01569a086.

- ^ Schleyer, P. von R., Donaldson, M. M., Nicholas, R. D., Cupas, C. (1973). "Adamantane". Organic Syntheses; Collected Volumes, vol. 5, p. 16.

- ^ a b Mansoori, G. Ali (2007). Molecular building blocks for nanotechnology: from diamondoids to nanoscale materials and applications. Springer. pp. 48–55. ISBN 978-0-387-39937-9.

- ^ Steven V. Ley, Caroline M.R. Low (6 December 2012). Ultrasound in Synthesis. Springer. ISBN 978-3-642-74672-7. Archived from the original on 27 April 2023. Retrieved 14 March 2023.

- ^ a b c Windsor CG, Saunderson DH, Sherwood JN, Taylor D, Pawley GS (1978). "Lattice dynamics of adamantane in the disordered phase". Journal of Physics C: Solid State Physics. 11 (9): 1741–1759. Bibcode:1978JPhC...11.1741W. doi:10.1088/0022-3719/11/9/013.

- ^ a b c Drabble JR, Husain AH (1980). "Elastic properties of adamantane single crystals". Journal of Physics C: Solid State Physics. 13 (8): 1377–1380. Bibcode:1980JPhC...13.1377D. doi:10.1088/0022-3719/13/8/008.

- ^ Landa, S., Machácek, V. (1933). "Sur l'adamantane, nouvel hydrocarbure extrait de naphte". Collection of Czechoslovak Chemical Communications. 5: 1–5. doi:10.1135/cccc19330001.

- ^ Landa, S., Machacek, V., Mzourek, M., Landa, M. (1933), "Title unknown", Chem. Abstr., 27: 5949

- ^ a b c "Synthesis of adamantane" (in Russian). Archived from the original on 2012-03-06. Retrieved 2009-12-11. Special practical problem for the students of IV year. Department of Petroleum Chemistry and Organic Catalysis MSU.

- ^ a b Bagriy EI (1989). "Methods for hydrocarbon adamantane series". Adamantane: Synthesis, properties, application. Moscow: Nauka. pp. 58–123. ISBN 5-02-001382-X. Archived from the original on 2024-03-08. Retrieved 2016-09-23.

- ^ "Adamantane". Encyclopedia of Chemistry (in Russian). Archived from the original on 2012-03-06. Retrieved 2009-12-11.

- ^ a b Vijayakumar, V., et al. (2001). "Pressure induced phase transitions and equation of state of adamantane". J. Phys.: Condens. Matter. 13 (9): 1961–1972. Bibcode:2001JPCM...13.1961V. doi:10.1088/0953-8984/13/9/318. S2CID 250802662.

- ^ Anastassakis, E., Siakavellas, M. (1999). "Elastic and Lattice Dynamical Properties of Textured Diamond Films". Physica Status Solidi B. 215 (1): 189–192. Bibcode:1999PSSBR.215..189A. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1521-3951(199909)215:1<189::AID-PSSB189>3.0.CO;2-X.

- ^ Mansoori, G. Ali (2005). Principles of nanotechnology: molecular-based study of condensed matter in small systems. World Scientific. p. 12. ISBN 981-256-154-4.

- ^ Wright, John Dalton (1995). Molecular crystals. Cambridge University Press. p. 28. ISBN 0-521-47730-1.

- ^ a b NMR, IR and mass spectra of adamantane can be found in the SDBS database Archived 2023-03-06 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ March, J. (1987). Organic chemistry. Reactions, mechanisms, structure. Advanced course for universities and higher education chemical. Vol. 1. M.: World. p. 137.

- ^ Applequist, J., Rivers, P., Applequist, D. E. (1969). "Theoretical and experimental studies of optically active bridgehead-substituted adamantanes and related compounds". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 91 (21): 5705–5711. doi:10.1021/ja01049a002.

- ^ Hamill, H., McKervey, M. A. (1969). "The resolution of 3-methyl-5-bromoadamantanecarboxylic acid". Chem. Comm. (15): 864. doi:10.1039/C2969000864a.

- ^ Acar HY, Jensen JJ, Thigpen K, McGowen JA, Mathias LJ (2000). "Evaluation of the Spacer Effect on Adamantane-Containing Vinyl Polymer T g's". Macromolecules. 33 (10): 3855–3859. Bibcode:2000MaMol..33.3855A. doi:10.1021/ma991621j.

- ^ Mathias LJ, Jensen J, Thigpen K, McGowen J, McCormick D, Somlai L (2001). "Copolymers of 4-adamantylphenyl methacrylate derivatives with methyl methacrylate and styrene". Polymer. 42 (15): 6527–6537. doi:10.1016/S0032-3861(01)00155-0.

- ^ Schleyer P. R., Fort R. C., Watts W. E. (1964). "Stable Carbonium Ions. VIII. The 1-Adamantyl Cation". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 86 (19): 4195–4197. doi:10.1021/ja01073a058.

- ^ Olah GA, Prakash GK, Shih JG, Krishnamurthy VV, Mateescu GD, Liang G, Sipos G, Buss V, Gund TM, Schleyer Pv (1985). "Bridgehead adamantyl, diamantyl, and related cations and dications". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 107 (9): 2764–2772. doi:10.1021/ja00295a032.

- ^ Smith, W., Bochkov A., Caple, R. (2001). Organic Synthesis. Science and art. M.: World. p. 573. ISBN 5-03-003380-7.

- ^ Bremer M, von Ragué Schleyer P, Schötz K, Kausch M, Schindler M (1987). "Four-Center Two-Electron Bonding in a Tetrahedral Topology. Experimental Realization of Three-Dimensional Homoaromaticity in the 1,3-Dehydro-5,7-adamantanediyl Dication". Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English. 26 (8): 761–763. doi:10.1002/anie.198707611.

- ^ Geluk HW, Keizer VG (1973). "Adamantanone". Organic Syntheses. 53: 8. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.053.0008.

- ^ 2-Adamantanecarbonitrile Archived 2012-07-10 at the Wayback Machine Organic Syntheses, Coll. Vol. 6, p. 41 (1988); Vol. 57, p. 8 (1977).

- ^ Schleyer P. R., Nicholas R. D. (1961). "The Preparation and Reactivity of 2-Substituted Derivatives of Adamantane". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 83 (1): 182–187. doi:10.1021/ja01462a036.

- ^ a b Nesmeyanov, A. N. (1969). Basic organic chemistry (in Russian). p. 664.

- ^ Olah, George A., Welch JT, Vankar YD, Nojima M, Kerekes I, Olah JA (1979). "Pyridinium poly (hydrogen fluoride): a convenient reagent for organic fluorination reactions". Journal of Organic Chemistry. 44 (22): 3872–3881. doi:10.1021/jo01336a027.

- ^ Olah, George A., Shih JG, Singh BP, Gupta BG (1983). "Ionic fluorination of adamantane, diamantane, and triphenylmethane with nitrosyl tetrafluoroborate/pyridine polyhydrogen fluoride (PPHF)". Journal of Organic Chemistry. 48 (19): 3356–3358. doi:10.1021/jo00167a050.

- ^ Rozen, Shlomo., Gal C (1988). "Direct synthesis of fluoro-bicyclic compounds with fluorine". Journal of Organic Chemistry. 53 (12): 2803–2807. doi:10.1021/jo00247a026.

- ^ Koch, H., Haaf, W. (1964). "1-Adamantanecarboxylic Acid". Organic Syntheses. 44: 1. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.044.0001.

- ^ Cohen, Zvi, Varkony, Haim, Keinan, Ehud, Mazur, Yehuda (1979). "Tertiary alcohols from hydrocarbons by ozonation on silica gel: 1-adamantanol". Organic Syntheses. 59: 176. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.059.0176.

- ^ Chalais S, Cornélis A, Gerstmans A, Kołodziejski W, Laszlo P, Mathy A, Métra P (1985). "Direct clay-catalyzed Friedel-Crafts arylation and chlorination of the hydrocarbon adamantane". Helvetica Chimica Acta. 68 (5): 1196–1203. doi:10.1002/hlca.19850680516.

- ^ Smith, George W., Williams, Harry D. (1961). "Some Reactions of Adamantane and Adamantane Derivatives". J. Org. Chem. 26 (7): 2207–2212. doi:10.1021/jo01351a011.

- ^ Moiseev, I. K., Doroshenko, R. I., Ivanova, V. I. (1976). "Synthesis of amantadine via the nitrate of 1-adamantanol". Pharmaceutical Chemistry Journal. 10 (4): 450–451. doi:10.1007/BF00757832. S2CID 26161105.

- ^ Watanabe, Keiji, et al. (2001). "Resist Composition and Pattern Forming Process". United States Patent Application 20010006752. Bandwidth Market, Ltd. Archived from the original on September 4, 2011. Retrieved 14 October 2005.

- ^ Morcombe, Corey R., Zilm, Kurt W. (2003). "Chemical Shift referencing in MAS solid state NMR". J. Magn. Reson. 162 (2): 479–486. Bibcode:2003JMagR.162..479M. doi:10.1016/S1090-7807(03)00082-X. PMID 12810033.

- ^ Lenzke, K., Landt, L., Hoener, M., et al. (2007). "Experimental determination of the ionization potentials of the first five members of the nanodiamond series". J. Chem. Phys. 127 (8): 084320. Bibcode:2007JChPh.127h4320L. doi:10.1063/1.2773725. PMID 17764261. S2CID 3131583.

- ^ Maugh T (1979). "Panel urges wide use of antiviral drug". Science. 206 (4422): 1058–60. Bibcode:1979Sci...206.1058M. doi:10.1126/science.386515. PMID 386515.

- ^ Sonnberg, Lynn (2003). The Complete Pill Guide: Everything You Need to Know about Generic and Brand-Name Prescription Drugs. Barnes & Noble Publishing. p. 87. ISBN 0-7607-4208-1.

- ^ Blanpied TA, Clarke RJ, Johnson JW (2005). "Amantadine inhibits NMDA receptors by accelerating channel closure during channel block". Journal of Neuroscience. 25 (13): 3312–22. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4262-04.2005. PMC 6724906. PMID 15800186.

- ^ Boukrinskaia, A. G., et al. "Polymeric Adamantane Analogues" (U.S. Patent 5,880,154). Retrieved 2009-11-05.[dead link]

- ^ Banister SD, Wilkinson SM, Longworth M, Stuart J, Apetz N, English K, Brooker L, Goebel C, Hibbs DE, Glass M, Connor M, McGregor IS, Kassiou M (2013). "The synthesis and pharmacological evaluation of adamantane-derived indoles: Novel cannabimimetic drugs of abuse". ACS Chemical Neuroscience. 4 (7): 1081–92. doi:10.1021/cn400035r. PMC 3715837. PMID 23551277.

- ^ "AIS-EHT1 Micro End Hall Thruster – Applied Ion Systems". Archived from the original on 2021-10-28. Retrieved 2021-02-22.

- ^ "Adamantane". Krugosvet (in Russian). Archived from the original on 6 November 2009. Retrieved 2009-11-11.

- ^ Jeong, H. Y. (2002). "Synthesis and characterization of the first adamantane-based poly (p-phenylenevinylene) derivative: an intelligent plastic for smart electronic displays". Thin Solid Films. 417 (1–2): 171–174. Bibcode:2002TSF...417..171J. doi:10.1016/S0040-6090(02)00569-2.

- ^ Ramezani, Hamid, Mansoori, G. Ali (2007). Diamondoids as Molecular Building Blocks for Nanotechnology. Topics in Applied Physics. Vol. 109. pp. 44–71. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-39938-6_4. ISBN 978-0-387-39937-9.

- ^ Markle RC (2000). "Molecular building blocks and development strategies for molecular nanotechnology". Nanotechnology. 11 (2): 89–99. Bibcode:2000Nanot..11...89M. doi:10.1088/0957-4484/11/2/309. S2CID 250914545.

- ^ Garcia JC, Justo JF, Machado WV, Assali LV (2009). "Functionalized adamantane: building blocks for nanostructure self-assembly". Phys. Rev. B. 80 (12) 125421. arXiv:1204.2884. Bibcode:2009PhRvB..80l5421G. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.80.125421. S2CID 118828310.

- ^ Vitall, J. J. (1996). "The Chemistry of Inorganic and Organometallic Compounds with Adamantane-Like Structures". Polyhedron. 15 (10): 1585–1642. doi:10.1016/0277-5387(95)00340-1.

- ^ Fischer, Jelena, Baumgartner, Judith, Marschner, Christoph (2005). "Synthesis and Structure of Sila-Adamantane". Science. 310 (5749): 825. doi:10.1126/science.1118981. PMID 16272116. S2CID 23192033.

- ^ Mancini I, Guella G, Frostin M, Hnawia E, Laurent D, Debitus C, Pietra F (2006). "On the First Polyarsenic Organic Compound from Nature: Arsenicin a from the New Caledonian Marine Sponge Echinochalina bargibanti". Chemistry: A European Journal. 12 (35): 8989–94. doi:10.1002/chem.200600783. PMID 17039560.

- ^ Tähtinen P, Saielli G, Guella G, Mancini I, Bagno A (2008). "Computational NMR Spectroscopy of Organoarsenicals and the Natural Polyarsenic Compound Arsenicin A". Chemistry: A European Journal. 14 (33): 10445–52. doi:10.1002/chem.200801272. PMID 18846604.

- ^ Guella G, Mancini I, Mariotto G, Rossi B, Viliani G (2009). "Vibrational analysis as a powerful tool in structure elucidation of polyarsenicals: a DFT-based investigation of arsenicin A". Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics. 11 (14): 2420–2427. Bibcode:2009PCCP...11.2420G. doi:10.1039/b816729j. PMID 19325974.

- ^ Di Lu, A. David Rae, Geoff Salem, Michelle L. Weir, Anthony C. Willis, S. Bruce Wild (2010). "Arsenicin A, A Natural Polyarsenical: Synthesis and Crystal Structure". Organometallics. 29 (1): 32–33. doi:10.1021/om900998q. hdl:1885/58485. S2CID 96366756.

Adamantane

View on GrokipediaStructure and Nomenclature

Molecular Structure

Adamantane is a polycyclic saturated hydrocarbon with the molecular formula and a molecular weight of 136.23 g/mol. Its systematic IUPAC name is tricyclo[3.3.1.1^{3,7}]decane. The molecule exhibits a highly symmetric, cage-like tricyclic structure that closely resembles a subunit of the diamond crystal lattice, making it the prototypical diamondoid hydrocarbon. This rigid framework consists of four fused cyclohexane rings, each adopting a strain-free chair conformation, which contributes to the overall stability and tetrahedral geometry of the carbon skeleton.[1][11] The carbon atoms in adamantane are arranged such that four tertiary bridgehead carbons occupy positions 1, 3, 5, and 7, while six methylene () groups form the bridges at positions 2, 4, 6, 8, 9, and 10. This configuration ensures all carbon atoms are -hybridized with local tetrahedral symmetry. The C-C bond lengths are approximately 1.54 Å, and the C-C-C bond angles are nearly ideal at about 109.5°, eliminating angle strain. Additionally, the chair conformations of the fused rings minimize torsional strain, rendering adamantane one of the most strain-free polycyclic hydrocarbons known.[12][13][14] As the smallest stable member of the diamondoid family, adamantane encapsulates the essential geometric features of the diamond unit cell, with its carbon framework directly analogous to a portion of the extended diamond lattice. In the solid state at room temperature, adamantane forms a plastic crystal phase characterized by cubic symmetry, specifically a face-centered cubic lattice with space group and lattice parameter Å, containing four molecules per unit cell. This disordered arrangement allows for molecular reorientation while maintaining overall lattice integrity.[15]Nomenclature

The name "adamantane" was coined by Vladimir Prelog and Robert Seiwerth in 1941 upon its first chemical synthesis, derived from the Greek word "adamas," meaning "unconquerable" or "indestructible," reflecting its rigid, diamond-like cage structure. According to IUPAC recommendations, the retained name "adamantane" is preferred over its systematic nomenclature for the parent hydrocarbon, which is tricyclo[3.3.1.1^{3,7}]decane; this systematic name follows the von Baeyer system for naming polycyclic saturated hydrocarbons, where the numbers in brackets denote the lengths of bridges and the positions of additional bridges between main chain atoms.[16][17] In the standard numbering system for adamantane, the four bridgehead (tertiary) carbon atoms are assigned positions 1, 3, 5, and 7, with the remaining methylene (secondary) carbons numbered 2, 4, 6, 8, 9, and 10 to ensure the lowest possible locants for substituents and maintain symmetry.[1] Substituents are distinguished by their attachment to either tertiary bridgehead positions (e.g., position 1) or secondary methylene positions (e.g., position 2). Derivatives of adamantane are named by adding functional group suffixes or prefixes to the parent name "adamantane," with locants specifying the position; for example, the alcohol with a hydroxy group at a bridgehead carbon is called adamantan-1-ol (also known as 1-adamantanol), while the corresponding radical or substituent group derived from a bridgehead position is termed adamantyl or 1-adamantyl. In chemical literature, the adamantyl group is commonly abbreviated as "Ad."[18] Adamantane represents the most stable isomer among the CH diamondoid hydrocarbons, often distinguished from less stable isomers such as protoadamantane by its high symmetry and strain-free chair conformations; early literature sometimes referred to it as "sym-adamantane" to emphasize this symmetry.[19]Physical Properties

Hardness and Mechanical Properties

Adamantane's rigid, strain-free cage structure confers exceptional mechanical stability despite the relative softness of its molecular crystal. The diamond-like arrangement of carbon atoms results in a highly symmetric framework with no angle strain, enabling the molecule to withstand significant stress without deformation. This rigidity is evident in the crystal's low compressibility, with a bulk modulus on the order of 10 GPa, allowing it to endure high pressures akin to larger diamondoids while maintaining structural integrity. The compound exhibits a density of 1.07 g/cm³, reflecting efficient molecular packing due to its tetrahedral geometry. Vibrational modes within the cage, particularly the symmetric C-C stretches, further enhance this rigidity by distributing energy evenly across the framework, precluding significant flexibility or distortion under mechanical load. In contrast to strained polycyclics like norbornane, which undergo facile rearrangements due to bond angle deviations, adamantane's seamless chair-boat-chair conformation ensures superior mechanical resilience.[20] Adamantane demonstrates high thermal stability, remaining intact up to 400 °C in an inert atmosphere, attributed to strong van der Waals interactions and the symmetric cage that minimizes entropy-driven disorder. Its melting point is 270 °C, unusually elevated for a C₁₀H₁₆ hydrocarbon, while it sublimes at reduced pressure with an estimated boiling point of 191 °C. Decomposition at higher temperatures proceeds via multi-step dehydrogenation and ring-opening pathways, as the strain-free structure precludes retro-Diels-Alder fragmentation observed in less stable polycyclics.[21][22][23][24]Spectroscopic Properties

Adamantane's spectroscopic properties are characterized by the simplicity arising from its high Td symmetry, which results in a limited number of distinct signals in various spectra due to the equivalence of its four bridgehead CH groups and six equivalent CH₂ groups. This symmetry group dictates that only two types of hydrogen and two types of carbon environments exist, facilitating straightforward identification in routine analyses.[1] In nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, adamantane exhibits two signals in the ¹H NMR spectrum in CDCl₃ solvent: the bridgehead protons appear at approximately δ 1.87 ppm (1H, multiplet), while the methylene protons resonate at δ 1.76 ppm (12H, broad singlet).[25] Similarly, the ¹³C NMR spectrum displays two signals: the bridgehead carbons at δ 37.85 ppm and the methylene carbons at δ 28.46 ppm, reflecting the molecule's symmetric cage structure.[26] These chemical shifts serve as standards in solid-state NMR, with the bridgehead ¹³C signal precisely at 37.777 ± 0.003 ppm at 25°C relative to tetramethylsilane.[27] The infrared (IR) spectrum of adamantane features characteristic aliphatic C-H stretching vibrations in the 2900–3000 cm⁻¹ region and C-H bending modes around 1450 cm⁻¹, indicative of unstrained alkane functionalities without the elevated frequencies typical of ring strain.[28] Additional cage vibrations appear below 1300 cm⁻¹, such as symmetric deformations, but the absence of absorptions signaling angular distortion underscores its diamondoid geometry.[29] Raman spectroscopy highlights the molecule's symmetric breathing mode of the cage at approximately 780 cm⁻¹, a strong feature arising from the Td-symmetric radial expansion and contraction, which is prominent due to the lack of change in molecular dipole.[30] Other Raman-active modes include C-H deformations around 1300–1400 cm⁻¹, providing complementary vibrational information to IR data for structural confirmation. In mass spectrometry (electron ionization), the molecular ion appears at m/z 136 (C₁₀H₁₆⁺), often as the base peak, with a characteristic fragmentation via loss of a methyl radical to yield m/z 121 (C₉H₁₃⁺), followed by further losses leading to peaks at m/z 79 and 93.[1] This pattern is diagnostic for the intact cage and stepwise retro-Diels-Alder-like cleavages. Ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy reveals no significant absorption bands above 200 nm, consistent with its saturated hydrocarbon nature lacking conjugated π-systems; absorptions occur only in the vacuum-UV region below 180 nm due to σ→σ* transitions.[31]Optical Properties

Adamantane exhibits no optical activity due to its achiral nature, stemming from the high tetrahedral (T_d) point group symmetry of the molecule, which includes multiple planes of symmetry and rotation axes that preclude chirality.[32] This symmetry results in a specific rotation of [α]_D = 0, as confirmed in early structural studies where the absence of rotation supported the proposed diamond-like cage architecture.[33] The optical inactivity of adamantane was historically instrumental in verifying its symmetric structure during the synthesis and characterization efforts in the mid-20th century, distinguishing it from potential asymmetric isomers.[34] In the solid state, adamantane crystals adopt a cubic structure with Fd\overline{3}m space group symmetry, leading to isotropic optical behavior and negligible birefringence. The refractive index at the sodium D line (n_D) is approximately 1.568, reflecting the dense, non-polar hydrocarbon framework suitable for light propagation with minimal dispersion in certain applications.[35] Adamantane demonstrates high transparency across the ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) spectrum, with an absorption onset below 200 nm in the vacuum ultraviolet (VUV) region, attributed to σ → σ* transitions in the C-C bonds.[31] This optical clarity positions adamantane as a candidate for transparent materials in photonic devices, though its monomeric form shows limited birefringence compared to extended diamondoid polymers, which can display enhanced anisotropic responses due to chain alignment.[36] Regarding emission properties, adamantane lacks observable fluorescence in the visible range under typical excitation conditions, with phosphorescence being negligible owing to the absence of heavy atoms or extended conjugation that could facilitate intersystem crossing.[37] However, when excited in the VUV region (around 6-8 eV), it displays broad intrinsic photoluminescence centered in the ultraviolet, arising from localized excitonic states within the cage structure, though this effect is weak and not prominent in standard optical assays.[31]Occurrence and Synthesis

Natural Occurrence

Adamantane was first isolated in 1933 from petroleum sourced from the Hodonín oil fields in Czechoslovakia by chemists Stanislav Landa and V. Macháček using fractional distillation techniques.[4] This discovery highlighted its presence as a minor component in certain crude oils, with concentrations typically ranging from tens to several hundred parts per million (ppm), though higher levels up to approximately 0.1% have been reported in specific shale oils such as those from the Gulong Formation.[38] Adamantane occurs naturally in petroleum reservoirs and associated natural gas deposits worldwide, including major basins like the North Sea and the Gulf of Mexico, where it is often found alongside higher diamondoids in condensate fractions.[39] It is also present in shale oils and bitumens, serving as a key biomarker for assessing thermal maturity in hydrocarbon source rocks, with ratios of adamantane isomers (e.g., 1-methyladamantane to 2-methyladamantane) indicating catagenetic stages between 1.0% and 2.3% vitrinite reflectance (EasyRo).[40][41] The origins of adamantane in these geological settings are primarily linked to the thermal maturation of organic matter during diagenesis and catagenesis, where polycyclic hydrocarbons rearrange under high-temperature, Lewis acid-catalyzed conditions to form stable cage structures; biogenic influences, such as microbial degradation of larger diamondoids, may contribute in less mature environments.[42][43] Extraction from natural sources typically involves fractional distillation of petroleum naphtha or higher-boiling fractions, followed by selective adsorption or crystallization to isolate the compound.[44]Historical Discovery

The discovery of adamantane began in 1933 when Czech chemists Stanislav Landa and Vladimir Macháček isolated a novel crystalline hydrocarbon (C10H16) from the higher-boiling fractions of petroleum obtained from the Hodonín oil field in Czechoslovakia.[45] Working at the Bata Research Laboratories in Zlín, Landa's team purified the compound through repeated crystallization and identified its empirical formula via combustion analysis, noting its remarkable stability and high melting point of 210°C.[4] The name "adamantane" was suggested by Rudolf Lukeš during a casual discussion with Landa, drawing from the Greek word adamas meaning "unconquerable," in reference to its diamond-like rigidity and resistance to chemical degradation.[45] Landa proposed a tricyclic cage structure resembling a fragment of the diamond lattice based on degradative studies and molecular weight determination, though definitive confirmation awaited further evidence.[4] In 1941, amid wartime constraints in occupied Czechoslovakia, Vladimir Prelog, guided by Lukeš at the Technical University in Prague, achieved the first laboratory synthesis of adamantane through a multi-step process involving the Diels-Alder reaction of 1,3-dichloro-2-propanol derivatives followed by dehalogenation and hydrogenation.[4] This total synthesis not only verified Landa's proposed structure but also highlighted adamantane's potential as a model for polycyclic hydrocarbons, aligning with Prelog's broader research on stereochemistry in bridged systems that later contributed to his 1975 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.[3] Prelog's work marked a pivotal milestone, shifting focus from isolation to synthetic accessibility and inspiring studies on related diamondoid compounds.[45] The 1950s saw advancements in synthetic routes, with Paul von R. Schleyer reporting in 1957 an improved total synthesis via the isomerization and cyclization of tetrahydrotricyclo[5.2.1.0]decene precursors, yielding adamantane in higher efficiency and paving the way for scalable production.[3] By the 1960s, interest surged at industrial laboratories, including Exxon, where researchers like Robert B. Bernstein adopted and popularized the name "adamantane" in English-language publications while exploring its properties for potential applications in lubricants and polymers, inspired by its exceptional hardness akin to diamond.[3] This period solidified adamantane's role as the foundational diamondoid, with X-ray crystallographic studies in 1964 confirming its Td-symmetric cage structure and face-centered cubic lattice. The 1970s and 1980s witnessed a boom in diamondoid research, driven by the global oil crises of 1973 and 1979, which heightened scrutiny of petroleum constituents and spurred investigations into adamantane's formation mechanisms and synthetic analogs for fuel additives and materials science.[3] Seminal reviews, such as Schleyer's 1971 Chemical Reviews article, synthesized these developments and emphasized adamantane's unique strain-free geometry.[3] In the 2020s, retrospectives have revisited these origins, underscoring Landa's pioneering isolation as the genesis of diamondoid chemistry and its enduring impact on organic synthesis and nanotechnology.[45]Synthetic Methods

The primary laboratory preparation of adamantane relies on the Lewis acid-catalyzed isomerization of tetrahydrodicyclopentadiene (THDCPD), a readily available saturated tricyclic precursor obtained via hydrogenation of the Diels-Alder dimer of cyclopentadiene. This approach was pioneered in 1957 by Paul von R. Schleyer, who employed aluminum chloride (AlCl₃) as the catalyst in a batch process at elevated temperatures (around 100–120°C), affording adamantane in 30–40% yield after fractional distillation and sublimation.[46] The reaction proceeds through a series of carbocation rearrangements, favoring the thermodynamically stable adamantane cage over other C₁₀H₁₆ isomers.[47] Modern scalable syntheses have optimized this isomerization for higher efficiency and industrial applicability, particularly through the use of platinum catalysts. A key advancement involves platinum supported on activated carbon (Pt/C, typically 5 wt%) in the presence of hydrogen fluoride (HF) and boron trifluoride (BF₃) as co-catalysts, under hydrogen pressure (0.5–2.0 MPa) at 40–80°C. Starting from THDCPD, this method achieves conversions of over 85% with adamantane selectivities exceeding 88%, enabling multikilogram production without excessive byproduct formation.[48] Variations using norbornane derivatives as alternative precursors have also been explored, leveraging similar Pt-catalyzed hydrogenolytic rearrangements to access the diamondoid framework with yields above 50%, though these remain less common than THDCPD-based routes due to precursor availability. Tetralin (1,2,3,4-tetrahydronaphthalene) derivatives offer another entry point via analogous catalytic rearrangements, providing scalable access to adamantane scaffolds in pharmaceutical contexts.[49] Alternative routes to adamantane include multi-component Diels-Alder cascades, where sequential cycloadditions of dienes and dienophiles construct the bridged polycyclic system from acyclic or monocyclic alkenes, followed by hydrogenation and rearrangement steps. These methods, while conceptually elegant, typically yield 20–50% overall and are better suited for substituted analogues rather than unsubstituted adamantane. Another strategy entails electrophilic adamantylation of aromatic substrates (e.g., via bridgehead carbocations), followed by partial hydrogenation and cyclization to form the core cage, though this is primarily applied to functionalized variants.[50] Synthesis challenges center on suppressing protadamantane and other proto-diamondoid isomers, which arise as kinetic products in carbocation-mediated rearrangements and can comprise up to 20–30% of crude mixtures under suboptimal conditions. Selective catalysis and precise temperature control mitigate this, while purification routinely employs vacuum sublimation (at 80–100°C), exploiting adamantane's high thermal stability and low solubility to isolate >99% pure material.[51] In terms of economic viability, synthetic methods have surpassed natural extraction from petroleum fractions, where adamantane occurs at concentrations below 0.1% and requires energy-intensive separation, rendering it cost-prohibitive; large-scale isomerization now dominates production.[50]Chemical Properties and Reactivity

General Reactivity

Adamantane displays remarkable thermal and chemical stability, owing to its strain-free, rigid diamondoid cage structure and the tertiary bridgehead carbons that effectively resist Wagner-Meerwein rearrangements under typical conditions.[3] This structural feature also enforces selectivity in electrophilic reactions, where attack preferentially occurs at the methylene (secondary) carbons rather than the bridgehead (tertiary) positions, analogous to Bredt's rule prohibiting double bonds at bridgeheads in small-ring systems.[3] The molecule exhibits resistance to radical-mediated processes and shows low reactivity toward Friedel-Crafts-type alkylations in the absence of activating or directing groups, reflecting its overall chemical inertness as a saturated hydrocarbon.[3][50] Acid-base properties of adamantane include weak C-H acidity at the bridgehead positions, with an estimated pKa of approximately 50, consistent with tertiary C-H bonds in hydrocarbons. In terms of solubility, adamantane is poorly soluble in water but readily dissolves in nonpolar solvents, characterized by a logP value of 3.8.[1] Electrochemical studies reveal irreversible oxidation behavior at high potentials (above 2.5 V vs. SCE), underscoring its high resistance to oxidative degradation.[52]Adamantane Cations

The 1-adamantyl cation is a tertiary carbocation formed at the bridgehead carbon of the adamantane framework, exhibiting exceptional stability attributable to extensive hyperconjugation involving 12 β C-H bonds from the three adjacent methylene groups.[53] This hyperconjugation delocalizes the positive charge across the symmetric cage structure, shortening the adjacent C-C bonds and contributing to the ion's resistance to rearrangement.[54] Unlike less constrained tertiary cations, the rigid diamondoid geometry enforces a classical, planar configuration at the carbocation center, as confirmed by X-ray crystallography of related derivatives.[55] The 1-adamantyl cation is typically generated through the solvolysis of 1-adamantyl tosylate in ionizing solvents, proceeding via an SN1 mechanism without neighboring group participation due to the inaccessible backside of the bridgehead position.[56] In highly ionizing media, such as aqueous acetone, the solvolysis rate of 1-adamantyl derivatives approaches that of tert-butyl analogs, highlighting the cation's inherent stability despite the cage's steric constraints.[57] Wagner-Meerwein rearrangements are minimal in the 1-adamantyl cation owing to the symmetric structure, which offers no energetic incentive for 1,2-shifts, although in certain substituted cases or under forcing conditions, migration to form the less stable 2-adamantyl cation can occur preferentially over bridgehead retention.[58][59] Spectroscopic characterization of persistent adamantyl cations has been achieved in superacid media, such as Magic Acid (FSO₃H–SbF₅), where ¹H NMR reveals distinct signals for the methine and methylene protons, with deshielding at the α-position indicative of the positive charge.[53] These ions serve as prototypical models in mechanistic studies of carbocation behavior, particularly to delineate classical tertiary structures from non-classical counterparts like the 2-norbornyl cation, due to their lack of bridging and high barriers to hydride shifts.[53] Recent density functional theory (DFT) computations have elucidated the energetics of adamantane cation formation, calculating ΔG values for ionization and isomerization pathways in the gas phase, confirming the 1-adamantyl structure as a global minimum with barriers exceeding 20 kcal/mol for rearrangements.[60] These studies underscore the role of cage symmetry in stabilizing the cation against fragmentation or internal conversion upon photoexcitation.Electrophilic and Functionalization Reactions

Electrophilic reactions of adamantane typically proceed via carbocation intermediates at the bridgehead (tertiary) position due to the stability of the resulting adamantyl cation, though selectivity can favor methylene (secondary) sites under certain conditions. Functionalization often involves halogenation, carboxylation, and oxidation, with bridgehead substitution preferred for ionic mechanisms but methylene sites accessible via radical pathways. Poly-substitution is generally avoided without prior activation, as the core structure's rigidity limits further reactivity. These transformations enable the synthesis of key derivatives for further applications. Bromination of adamantane can occur selectively at the methylene position to yield 2-bromoadamantane using N-bromosuccinimide (NBS) under radical conditions, typically in carbon tetrachloride at reflux, achieving approximately 70% yield. Bridgehead bromination to 1-bromoadamantane requires forcing electrophilic conditions, such as anhydrous AgSbF6 catalysis in CH2Cl2 at 74.5 °C with Br2, providing 54% yield.[61] Fluorination predominantly targets the bridgehead position, yielding 1-fluoro adamantane. Treatment with XeF2 in carbon disulfide at room temperature affords the product in moderate yield, though side products and tar formation reduce efficiency.[62] Carboxylation via the Koch reaction involves adamantane with CO in concentrated H2SO4 at low temperature, generating the adamantyl cation that traps CO to form 1-adamantanecarboxylic acid after hydrolysis. This method highlights the utility of superacid media for direct C-C bond formation at the bridgehead. Oxidation reactions functionalize adamantane to alcohols and ketones. KMnO4 in basic conditions oxidizes adamantane to 1-adamantanol with moderate selectivity at the tertiary site, often requiring phase-transfer catalysis for efficiency. RuO4, generated in situ from RuO2 and NaIO4 in biphasic media, provides 1-adamantanol in 82% yield or adamantane-2-one via secondary alcohol intermediates.[63] A recent 2025 advancement employs bacterial enzymatic oxidation (e.g., via cytochrome P450 variants) for regiospecific diol formation, such as 1,3-adamantanediol, with significant yield and high tertiary selectivity.[5] Other electrophilic functionalizations include nitration with mixed acid (HNO3/H2SO4) at 0 °C, yielding 1-nitro adamantane primarily at the bridgehead. Sulfonation is limited due to competing dehydration and polymerization.| Reaction | Product | Conditions | Yield (%) | Selectivity Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bromination (methylene) | 2-Bromoadamantane | NBS, CCl4, reflux | ~70 | Radical, 2° > 3° |

| Bromination (bridgehead) | 1-Bromoadamantane | Br2, AgSbF6, CH2Cl2, 74.5 °C | 54 | Electrophilic, bridgehead favored |

| Fluorination | 1-Fluoro adamantane | XeF2, CS2, rt | moderate | Bridgehead, tars common |

| Oxidation (alcohol) | 1-Adamantanol | RuO4 (cat.), NaIO4, CH2Cl2/H2O | 82 | Versatile for 1°/2° |

| Enzymatic oxidation | 1,3-Adamantanediol | Bacterial P450, aq. buffer, 30 °C | significant | Regiospecific diol |