Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

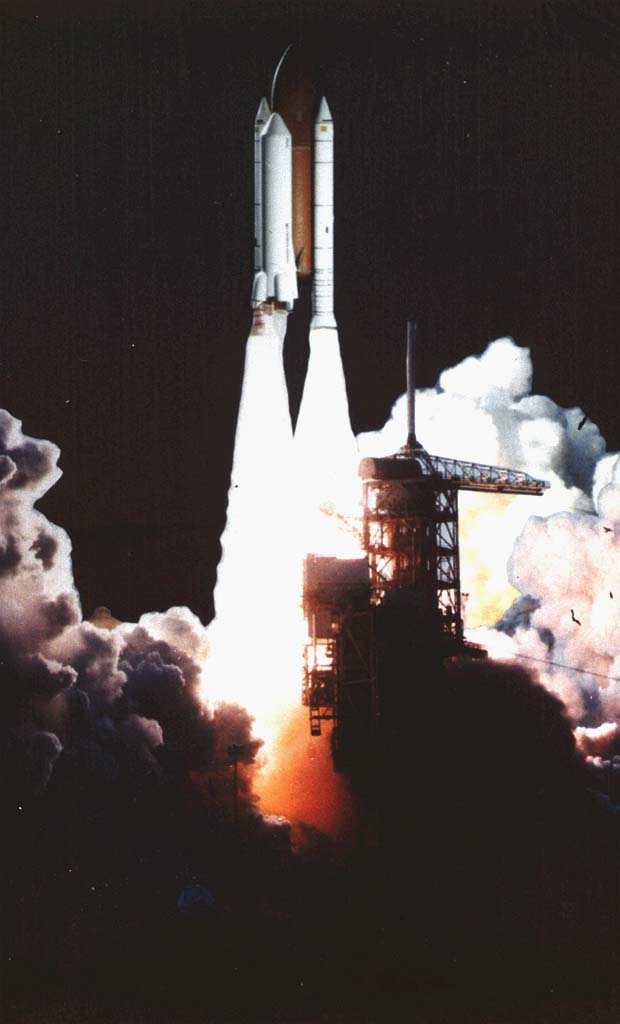

Shuttle-C

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2008) |

The Shuttle-C was a study by NASA to turn the Space Shuttle launch stack into a dedicated uncrewed cargo launcher.[1] The Space Shuttle external tank and Space Shuttle Solid Rocket Boosters (SRBs) would be combined with a cargo module to take the place of the Shuttle orbiter and include the main engines.[1] Various Shuttle-C concepts were investigated between 1984 and 1995.[2]

The Shuttle-C concept would theoretically cut development costs for a heavy launch vehicle by re-using technology developed for the shuttle program. End-of-life and Space Shuttle hardware would also have been used. One proposal even involved converting Columbia or Enterprise into a single-use cargo launcher. Before the loss of Space Shuttle Challenger, NASA had expected about 24 shuttle flights a year. In the aftermath of the Challenger incident, it became clear that this launch rate was not feasible for a variety of reasons.[3] With the Shuttle-C, it was thought that the lower maintenance and safety requirements for the uncrewed vehicle would allow a higher flight rate.[4][5]

The Shuttle-C would have been the main crew launch vehicle for the ILREC Piloted Lander in the International Lunar Resources Exploration Program.

In the early 1990s, NASA engineers planning a crewed mission to Mars included a Shuttle-C design to launch six non-reusable, 80-ton segments to create two Mars ships in Earth orbit. After President George W. Bush called for the end of the Space Shuttle by 2010, these proposed configurations were put aside.[citation needed]

As early as the 1970s, some iteration of the Shuttle-C had been studied (Encyclopedia Astronautica mentions it as "Class 1 SDV").[1] It was discussed in Gerard O'Neill's 1976 book The High Frontier: Human Colonies in Space, with artwork by Don Davis.[6]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Shuttle C". www.astronautix.com. Retrieved 2024-07-01.

- ^ "Shuttle-C". GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved 2009-01-20.

- ^ "Report of the Presidential Commission on the Space Shuttle Challenger Accident". NASA. 1986-06-06. Retrieved 2009-01-20.

- ^ "Shuttle-C, evolution to a heavy lift launch vehicle" (PDF). NASA/AIAA. 1989-07-13. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-09-20. Retrieved 2009-08-05.

- ^ Robert G. Eudy (1990-09-25). "Shuttle-C, heavy lift vehicle of the 90's". NASA/AIAA. Retrieved 2023-04-02.

- ^ "The Don Davis High Frontier Artshow". Space Studies Institute. Retrieved 2024-07-01.

External links

[edit]Shuttle-C

View on GrokipediaBackground

Early Concepts

The origins of Shuttle-C concepts trace back to 1970s NASA studies on shuttle-derived vehicles (SDVs), which sought to adapt Space Shuttle hardware for uncrewed heavy-lift cargo missions to enhance access to orbit beyond the orbiter's limitations. These early explorations focused on leveraging proven components to achieve higher payload capacities while minimizing development costs for future space infrastructure needs.[4] A key proposal was Boeing's Class 1 SDV, developed around 1977, which replaced the crewed orbiter with an expendable cargo shroud mounted atop the External Tank (ET), powered by the three Space Shuttle Main Engines (SSMEs) in a recoverable pod, and boosted by the two Solid Rocket Boosters (SRBs). This configuration emphasized uncrewed operations for heavy cargo delivery, with the SRBs designed for recovery and reuse to promote economic viability. The Interim Heavy Lift Launch Vehicle (IHLLV) represented a parallel concept, similarly deriving from Shuttle elements to serve as a bridge to advanced launch systems capable of supporting large-scale orbital activities.[4][5] Initial payload projections for these SDVs hovered around 50,000 kg to low Earth orbit (LEO), achieved through modifications to existing Shuttle hardware that allowed for larger cargo volumes without the mass penalties of a crew compartment. NASA reports from the era, including analyses of space transportation options, detailed how reusable SRBs and the ET could form the core of cost-effective, high-capacity cargo launchers, paving the way for sustained orbital operations.[4][5]Post-Challenger Rationale

The Challenger disaster on January 28, 1986, resulted in the destruction of the orbiter and the loss of its seven-member crew just 73 seconds after liftoff, prompting NASA to ground the entire Space Shuttle fleet for 32 months while implementing extensive safety modifications recommended by the Rogers Commission. This incident exposed the vulnerabilities of relying on crewed vehicles for routine cargo deliveries, as the Shuttle had been increasingly tasked with such missions despite its original design intent for mixed human and payload transport, thereby endangering astronauts in non-essential flights.[6] In the aftermath, NASA's internal reviews from 1986 to 1987, including the Space Transportation Architecture Study and assessments by the Office of Technology Assessment, highlighted the need for an uncrewed heavy-lift alternative to supplement the Shuttle program and realize its pre-disaster objective of up to 24 flights per year—a rate deemed unattainable with the grounded fleet and heightened risk awareness.[7] These evaluations emphasized that separating cargo launches from crewed operations would mitigate safety risks, preserve the limited orbiter fleet for human spaceflight priorities, and enable higher overall launch cadences to support initiatives like the Space Station.[8] The Shuttle-C emerged from these deliberations as a dedicated cargo vehicle, drawing briefly on uncrewed derivative concepts explored in the 1970s but tailored to the post-Challenger emphasis on reliability and efficiency.[9] A key driver for Shuttle-C was its projected cost savings, with NASA estimating development at $1.8 billion (in fiscal year 1991 dollars) and operational costs at $424 million per launch (in fiscal year 1988 dollars)—substantially lower than those for crewed Shuttle missions, which included crew support and reusability overheads.[9][7] This efficiency stemmed from its cargo-only configuration, achieving payloads of 45,000 to 77,000 kg to low Earth orbit compared to the Shuttle's approximately 25,000 kg.[7] Relative to existing alternatives like the Titan IV, which was limited to about 21,800 kg to low Earth orbit and incurred higher per-kg costs for heavy payloads due to its expendable design without Shuttle heritage, Shuttle-C offered superior capacity and integration with existing infrastructure, potentially displacing multiple Titan launches for large-scale missions while lowering long-term program expenses.[7]Design

Vehicle Configuration

The Shuttle-C vehicle adapted the core structure of the Space Shuttle for uncrewed cargo operations, retaining two reusable four-segment Solid Rocket Boosters (SRBs) and an expendable External Tank (ET) while replacing the orbiter with a dedicated expendable cargo carrier mounted in a side configuration.[10] This layout leveraged existing Shuttle hardware to minimize development costs and risks, with the SRBs providing initial ascent thrust and the ET supplying cryogenic propellants to the carrier's engines.[1] The cargo module featured a cylindrical payload fairing with an internal payload bay measuring 4.6 meters in diameter and 25 meters in length, enabling accommodation of large unpressurized or modular payloads.[11] The overall vehicle stood approximately 56 meters tall, with a gross liftoff mass of around 2 million kilograms, depending on configuration.[10] Advanced variants of the cargo module supported payloads up to 77,100 kilograms to a 400-kilometer orbit at 28.5-degree inclination.[11] Avionics systems were simplified for autonomous operation, drawing from the Space Shuttle's guidance, navigation, and control (GN&C) architecture while eliminating crew-related redundancies and interfaces.[12] Key components included integrated computers, inertial measurement units, and thrusters housed in a recoverable propulsion and avionics module that separated post-main engine cutoff for parachute-assisted splashdown.[10] SRB recovery utilized parachutes for reuse, as in manned missions.[1] Studies also explored options for converting existing orbiters, such as Columbia or Enterprise, into single-use cargo carriers by removing wings, thermal protection, and crew systems to enhance payload capacity while using the familiar orbiter forward fuselage for payload integration.[11]Propulsion and Performance

The propulsion system of the Shuttle-C vehicle was derived from the Space Shuttle stack, utilizing two or three Space Shuttle Main Engines (SSMEs) mounted on the expendable cargo element (CE) to provide primary ascent thrust after solid rocket booster (SRB) separation.[13] Each SSME was capable of delivering up to 1,860 kN of vacuum thrust at 109% power level, enabling efficient liquid hydrogen/liquid oxygen propulsion for the core stage following SRB burnout.[14] The two SRBs provided the majority of the initial liftoff thrust and impulse during the first approximately two minutes of flight. For orbital maneuvers, such as insertion and circularization, the auxiliary propulsion system, derived from the Space Shuttle's orbital maneuvering system (OMS) and reaction control system (RCS), provided for orbit circularization, attitude control, and deorbit using hypergolic propellants.[2] Performance specifications for the Shuttle-C emphasized enhanced cargo delivery compared to the crewed Shuttle, with the Generation 1 configuration—featuring two SSMEs and a 4.6 m × 24.7 m cargo bay—capable of placing 45,400 kg into low Earth orbit (LEO).[15] The upgraded Generation 2 variant, planned for operational deployment by 1994, incorporated three SSMEs and structural optimizations to increase payload capacity to 77,100 kg to a 400 km circular orbit at 28.5° inclination.[15] The overall vehicle height measured 56 m, similar to the Space Shuttle stack, facilitating compatibility with existing Launch Complex 39 infrastructure while enabling uncrewed operations for improved reliability.[16] The flight profile mirrored the Space Shuttle's vertical stack launch sequence, with SRBs igniting at liftoff to provide maximum initial acceleration, followed by separation at approximately 125 seconds after burnout.[17] The SSMEs then continued burning until external tank (ET) depletion and separation around eight minutes into flight, propelling the CE and payload toward orbit insertion.[17] The absence of a crew compartment eliminated life-support overhead, allowing for simplified avionics and higher structural margins, which contributed to projected mission reliability exceeding 99%.[13]Development

Studies and Proposals

Following the Challenger disaster in 1986, NASA initiated formal studies in August 1987 for an uncrewed cargo variant of the Space Shuttle to augment heavy-lift capabilities and support increased launch rates for programs like the Space Station.[16] In November 1987, NASA awarded nine-month definition study contracts to industry teams led by Martin Marietta Corporation, United Technologies Corporation, and Rockwell International to evaluate vehicle configurations, integration with existing Shuttle systems, and development feasibility.[1] These initial studies culminated in a February 1988 award of an 18-month contract (NAS8-37144) to a broader consortium including Rockwell, Martin Marietta, Boeing, Teledyne, Intermetrics, and United Space Boosters for detailed concept refinement, emphasizing reuse of proven Shuttle elements like solid rocket boosters, external tanks, and main engines.[16] Under NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center leadership, the effort focused on preliminary designs that evolved avionics and guidance, navigation, and control (GN&C) systems from manned Shuttle heritage, incorporating autonomous ascent control and orbital operations initially planned via an Orbital Maneuvering Vehicle.[1] A key milestone came in fall 1988 with the USRA/NASA design proposal, which recommended Shuttle-C as the optimal Class I Shuttle-derived heavy-lift vehicle for 1990s operations, prioritizing compatibility with the National Space Transportation System and cost reductions through component commonality.[12] The studies extended into early 1989 with a one-year prolongation to address refinements, including avionics recovery systems housed in a reentry capsule for post-mission retrieval and reuse, aiming to mitigate spare parts shortages in the Shuttle fleet.[16][12] Overall study outcomes targeted a compressed development timeline of approximately four years to achieve initial operational capability by the mid-1990s, leveraging mature technologies to minimize risks.[1] Industry inputs during these phases estimated total development costs at $1.8 billion, reflecting the high degree of heritage from existing Shuttle infrastructure.[16]Technical Evaluations

Technical evaluations of the Shuttle-C concept involved detailed engineering analyses and trade studies to assess its viability as an uncrewed heavy-lift vehicle derived from the Space Shuttle system. These assessments focused on adapting existing infrastructure while addressing the unique requirements of an expendable cargo launcher, including propulsion configurations, avionics, and overall performance metrics. NASA conducted these studies in the late 1980s, emphasizing cost-effectiveness and integration with proven technologies to minimize development risks.[18] Avionics design for Shuttle-C centered on a compact reentry capsule to recover critical components post-mission, weighing approximately 2,150 pounds and including 1,000 pounds of avionics equipment. The preliminary recovery system utilized a three-stage parachute deployment: a ribbon hemispherical drogue at 65,000 feet, a conical ribbon parachute to extract the capsule at 45,000 feet, and a ram-air decelerator for landing at speeds up to 55 feet per second on skids at Edwards Air Force Base. Guidance, navigation, and control (GN&C) adaptations incorporated an inertial measurement unit (126 pounds), rate gyros (30 pounds), and accelerometers (8 pounds) to maintain six-degree-of-freedom control during reentry, with the system designed for autonomous operation or remote control via servo actuators. Software drew from established National Space Transportation System (NSTS) technologies, though specific adaptations from Shuttle Approach and Landing Tests (ALT) were not detailed in feasibility analyses. These elements ensured compatibility with Shuttle heritage while addressing the uncrewed vehicle's expendable nature, though challenges included high deceleration forces up to -3.3 g and thermal protection via an ablative shield weighing about 1,000 pounds.[12] Trade studies evaluated propulsion options, particularly comparing two versus three Space Shuttle Main Engines (SSMEs) for payload trade-offs. The two-SSME configuration reduced complexity and operational costs but limited payload capacity compared to the three-SSME variant, which offered higher performance at the expense of increased maintenance and refurbishment needs. Cost-benefit analyses highlighted that SSME-related expenses, including procurement at approximately $20 million per engine (with refurbishment adding $15 million), drove incremental launch costs to around $480 million for a three-engine setup in fiscal year 1991 dollars, providing no clear economic advantage over alternatives like the Titan IV due to these recurring burdens.[19][9] Feasibility reports from 1989 confirmed Shuttle-C's potential for heavy-lift operations, with a maximum capacity of up to 150,000 pounds to low Earth orbit (LEO) in the baseline configuration, scalable based on engine count. Integration with existing Shuttle infrastructure was a key strength, reusing elements like solid rocket boosters and the external tank to achieve this performance while leveraging facilities at Kennedy Space Center for minimal modifications. These evaluations projected operational readiness within four years at a development cost of about $1.8 billion, prioritizing near-term availability for cargo missions.[18][18][9] Identified challenges included higher recurring costs from procuring and maintaining new SSMEs, which offset payload gains and complicated economic viability compared to expendable launchers. Additionally, the design inherited Shuttle launch constraints from Kennedy Space Center, limiting nominal orbital inclinations to 28 degrees without costly trajectory modifications for higher angles.[9][20]Proposed Missions

Space Station Support

Shuttle-C was proposed as a key enabler for the assembly of Space Station Freedom by delivering large structural elements and modules to low Earth orbit, thereby augmenting the capabilities of the crewed Space Shuttle orbiter. In integration concepts developed during 1989 NASA studies, Shuttle-C would handle the transport of oversized payloads that exceeded the orbiter's volume and mass limits, such as pre-outfitted habitats and truss segments, allowing for a rephased assembly sequence in the early 1990s.[21][22] For instance, it could deliver modules weighing up to 45,400 kg (100,000 pounds) to a 407 km orbit at 28.5° inclination, facilitating the on-orbit construction of Freedom's core structure without requiring multiple crewed flights for initial heavy-lift tasks.[21] The vehicle's uncrewed design supported a higher launch cadence compared to the orbiter, with potential for 2-3 flights per year to orbit truss segments, laboratory modules, and habitation units, reducing overall mission complexity and crew exposure to risk during assembly.[22] These studies, conducted by NASA in collaboration with contractors like UTC, Martin Marietta, and Rockwell, evaluated two primary utilization scenarios: an early-phase approach where Shuttle-C launches preceded orbiter missions to establish foundational elements, and a later buildup phase for resupply and expansion.[21][22] This sequencing would minimize the number of launches needed, as Shuttle-C's 15-foot by 82-foot payload bay could accommodate fully integrated components that simplified on-orbit integration.[22] By providing greater payload mass—up to 77,000 kg in advanced configurations—and more frequent launches, Shuttle-C addressed limitations in the orbiter's 24,500 kg capacity to similar orbits, directly supporting NASA's objective of establishing a permanent human presence in low Earth orbit through efficient infrastructure deployment.[21][22] This approach not only enhanced assembly efficiency but also freed crewed shuttles for science and exploration missions, while restoring heavy-lift capabilities comparable to those of the Saturn program.[22] Overall, these benefits were projected to streamline Freedom's development, potentially enabling operational readiness by the mid-1990s if development began in fiscal year 1991.[21]Planetary Exploration

Shuttle-C was envisioned to support lunar exploration efforts by delivering components for piloted landers and large habitat segments up to 77 metric tons to low Earth orbit, enabling the assembly of infrastructure for sustained human presence on the Moon. This role aligned with NASA's post-1989 Space Exploration Initiative (SEI), including concepts like the International Lunar Resources Exploration Concept (ILREC; a proposed international lunar outpost architecture focusing on in-situ resource utilization), as depicted in NASA planning imagery.[23] With a payload capacity of up to 77,000 kg to low Earth orbit, Shuttle-C could transport the heavy, non-reusable elements required for lunar outposts, reducing reliance on smaller launchers and facilitating international collaboration in resource utilization.[24] For Mars missions, early 1990s NASA planning incorporated Shuttle-C to launch multiple large segments—potentially six non-reusable units up to 77 metric tons each—for orbital assembly of crewed transfer stages and habitats at Space Station Freedom. This modular approach would build trans-Mars injection vehicles, with total mission payloads ranging from 550 to 850 metric tons assembled from several launches, each delivering up to 77,000 kg of cargo including propellant tanks and structural modules. The design emphasized enabling a scalable crewed Mars architecture by leveraging Shuttle-C's heavy-lift performance for planetary probes and upper stages, supporting broader SEI goals of human expansion beyond low Earth orbit.[24][25]Cancellation

Budgetary and Political Factors

The Shuttle-C program was effectively canceled in 1990 as part of broader NASA budget constraints under President George H.W. Bush, with no development funding allocated in the fiscal year 1991 (FY1991) appropriations.[26] Although a House subcommittee approved $1.1 billion for initial construction in March 1990, the overall NASA budget faced tightening due to the Budget Enforcement Act of 1990, which imposed caps on discretionary spending and heightened scrutiny of high-cost space initiatives.[27] This lack of funding halted advancement following 1989 efforts, including the rollout of a full-scale mockup at Marshall Space Flight Center to build support for a proposed $1.5 billion development program.[26] Final studies and reports were archived without further progression, marking the end of the initiative after extensions from initial 1987 definition studies.[3] In the political landscape, the cancellation reflected a post-Cold War pivot toward fiscal restraint and reprioritization, with diminished congressional backing amid reduced national security-driven space spending.[27] Bush's administration initially sought a 24 percent NASA budget increase in early 1990 to support ambitious goals like the Space Exploration Initiative, but Congress rejected much of this, favoring international partnerships for Space Station Freedom over domestic heavy-lift expansions like Shuttle-C.[28] Uncertainty surrounding Space Station funding further eroded support, as lawmakers questioned the need for Shuttle-C amid emerging alternatives and a broader shift away from Shuttle dependency. Technical challenges, such as integration complexities, indirectly amplified these political hesitations by raising perceived risks. Economic analyses underscored the program's viability issues, with Office of Technology Assessment (OTA) studies estimating development costs at approximately $985 million (FY 1988 dollars) and per-launch expenses at $424 million, deeming it uncompetitive for low-volume missions compared to expendable vehicles like the Titan IV.[7] NASA internal reviews in February 1990 highlighted that Shuttle-C's $2 billion development plus $3.7 billion for 10 Space Station flights would exceed the $1.5 billion cost of 18 manned Shuttle missions, failing to justify the investment amid uncertain demand.[26] These critiques aligned with the initiation of the Evolved Expendable Launch Vehicle (EELV) program in the mid-1990s, which prioritized cost-effective commercial alternatives over Shuttle-derived systems. Although canceled, Shuttle-C concepts later influenced heavy-lift designs such as the Space Launch System.[29]Technical and Economic Challenges

The Shuttle-C program encountered substantial technical hurdles in engine production and system integration. The Space Shuttle Main Engines (SSMEs) required high-cost manufacturing processes, exacerbating overall development expenses. Integrating these engines into an uncrewed, partially expendable configuration introduced complexities such as modified thrust vectoring and thermal protection adaptations, yet offered no meaningful reliability improvements over the manned shuttle's design, as core propulsion and structural elements remained largely unchanged. Economic analyses in 1990, including those from the Office of Technology Assessment (OTA), revealed that Shuttle-C's lifecycle costs exceeded those of the Titan IV under low to moderate flight rates, primarily due to high fixed development and recurring element costs. Per-launch operational expenses for a three-engine Shuttle-C were projected at $424 million in fiscal year 1988 dollars, higher than the Titan IV's approximately $300 million per launch for comparable missions, with total program costs sensitive to launch cadence and failing to amortize investments effectively. Development timelines, initially targeted at four years, slipped beyond this benchmark in evaluations, further inflating expenses through extended facility preparations and testing delays.[7][9] Risk assessments underscored vulnerabilities in solid rocket booster (SRB) reuse and external tank (ET) utilization within a post-Challenger safety framework. The redesigned SRBs, implemented after the 1986 accident to address joint seal failures, raised refurbishment costs and turnaround times, diminishing anticipated savings from reuse while maintaining similar failure risks in probabilistic models. The expendable ET, optimized for the reusable shuttle's cryogenic handling and insulation needs, proved inefficient for high-volume cargo production, as its manufacturing process lacked economies of scale and introduced quality control issues without offsetting reusability benefits.[30][31] In comparative terms, Shuttle-C was outperformed by emerging commercial expendable launch options on cost-per-kilogram metrics, estimated at approximately $9,000 per kg to low Earth orbit (FY 1988 dollars). Vehicles like the Delta II achieved approximately $18,000–$22,000 per kg to low Earth orbit at the time, undercutting Shuttle-C's projected costs through simpler designs and higher production rates, while nascent commercial initiatives foreshadowed even lower costs via streamlined operations.[7]References

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Shuttle-C_with_ILREC_Piloted_Lander.png