Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Sirmur State

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2025) |

Key Information

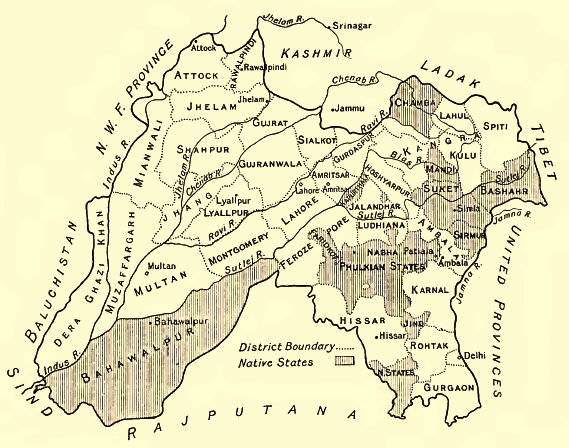

Sirmur (also spelled as Sirmor, Sirmaur, Sirmour, or Sirmoor) was a princely state of India, located in the region that is now the Sirmaur district of Himachal Pradesh. The state was also known as Nahan, after its main city, Nahan. The state ranked predominant amongst the Punjab Hill States. It had an area of 4,039 km2 and a revenue of 300,000 rupees in 1891.[citation needed]

History

[edit]Origin

[edit]According to Mian Goverdhan Singh in Wooden Temples of Himachal Pradesh, the principality of Sirmaur was founded in the 7th to 8th century by Maharaja of Parmar Rajputs, and Rathore noble.[1]

Nahan State

[edit]Nahan, the predecessor state of Sirmur, was founded by Soba Rawal in 1095 AD who assumed the name Raja Subans Prakash.[citation needed]

Near the end of the 12th century in the year 1195, a flood of the Giri River destroyed the old capital of Sirmaur-Tal, which killed Raja Ugar Chand.[1] A ruler of Jaisalmer, Raja Salivahana, thought this was an opportune time to attack the state as it was in a state of disarray due to the natural disaster and death of its ruler, so he sent his son Sobha to conquer the state.[1] The attack was successful and a new dynasty headed by Bhati Rajputs was established.[1] Sirmur was invaded by invader Jasrath's army, who also invaded fragments of Punjab and Jammu.[2]

Sirmur State

[edit]Eventually in 1621 Karm Parkash founded Nahan, the modern capital.[3] Budh Parkãsh, the next ruler, recovered Pinjaur for Aurangzeb’s foster-brother.[citation needed] Raja Mit Parkãsh gave an asylum to the Sikh Guru, Gobind Singh, permitting him to fortify Paonta in the Kiarda Dun; and it was at Bhangani in the Dun that the Guru defeated the Rajäs of Kahlur and Garhwäl in 1688.[3] But in 1710 Kirat Parkãsh, after defeating the Räja of Garhwal, captured Naraingarh, Morni, Pinjaur, and other territories from the Sikhs, and concluded an alliance with Amar Singh, Raja of Patiala, whom he aided in suppressing his rebellious Wazir; and he also fought in alliance with the Raja of Kahlür when Ghuläm Kãdir Khan, Rohilla, invaded that State.[4]

Rulers

[edit]The rulers of Sirmur bore the title "Maharaja" from 1911 onward [citation needed]

| Name | Portrait | Ruled from | Ruled until | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subhansh Prakash | 1095 | 1099 | ||

| Mahe Prakash | 1099 | 1117 | ||

| Udit Prakash | 1117 | 1127 | ||

| Kaul Prakash | 1127 | 1153 | ||

| Sumer Prakash | 1153 | 1188 | ||

| Suraj Prakash | 1188 | 1254 | ||

| Bhagat Prakash I | 1254 | 1336 | ||

| Jagat Prakash | 1336 | 1388 | ||

| Bir Prakash | 1388 | 1398 | ||

| Naket Prakash | 1398 | 1398 | ||

| Ratna Prakash | 1398 | 1413 | ||

| Garv Prakash | 1413 | 1432 | ||

| Brahm Prakash | 1432 | 1446 | ||

| Hams Prakash | 1446 | 1471 | ||

| Bhagat Prakash II | 1471 | 1538 | ||

| Dharam Prakash | 1538 | 1570 | ||

| Deep Prakash | 1570 | 1585 | ||

| Budh Prakash | 1605 | 1615 | ||

| Bhagat Prakash III | 1615 | 1620 | ||

| Karam Prakash I |

|

1621 | 1630 | |

| Mandhata Prakash |

|

1630 | 1654 | |

| Sobhag Prakash | 1654 | 1664 | ||

| Budh Prakash | 1664 | 1684 | [1][5] | |

| Mat Prakash | 1684 | 1704 | [1][5] | |

| Hari Prakash | 1704 | 1712 | [5] | |

| Bijay Prakash | 1712 | 1736 | ||

| Pratap Prakash | 1736 | 1754 | ||

| Kirat Prakash |

|

1754 | 1770 | |

| Jagat Prakash |

|

1770 | 1789 | |

| Dharam Prakash | 1789 | 1793 | ||

| Karam Prakash II (died 1820) | 1793 | 1803 | ||

| Ratan Prakash (installed by Gurkhas, hanged by the British in 1804) | 1803 | 1804 | ||

| Karma Prakash II (died 1820) | 1804 | 1815 | ||

| Fateh Prakash |

|

1815 | 1850 | |

| Raghbir Prakash | 1850 | 1856 | ||

| Shamsher Prakash |

|

1856 | 1898 | |

| Surendra Bikram Prakash |

|

1898 | 1911 | |

| Amar Prakash | 1911 | 1933 | ||

| Rajendra Prakash | 1933 | 1947 | ||

| Lakshraj Prakash | 2013 | [6][7] |

Demographics

[edit]| Religious group |

1901[8] | 1911[9][10] | 1921[11] | 1931[12] | 1941[13] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | |

| Hinduism |

128,478 | 94.69% | 130,276 | 94.05% | 132,431 | 94.29% | 139,031 | 93.58% | 146,199 | 93.7% |

| Islam |

6,414 | 4.73% | 6,016 | 4.34% | 6,449 | 4.59% | 7,020 | 4.73% | 7,374 | 4.73% |

| Sikhism |

688 | 0.51% | 2,142 | 1.55% | 1,449 | 1.03% | 2,413 | 1.62% | 2,334 | 1.5% |

| Jainism |

61 | 0.04% | 49 | 0.04% | 65 | 0.05% | 52 | 0.04% | 81 | 0.05% |

| Christianity |

46 | 0.03% | 37 | 0.03% | 44 | 0.03% | 52 | 0.04% | 38 | 0.02% |

| Buddhism |

0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 10 | 0.01% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% |

| Zoroastrianism |

0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% |

| Judaism |

0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% |

| Others | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% |

| Total population | 135,687 | 100% | 138,520 | 100% | 140,448 | 100% | 148,568 | 100% | 156,026 | 100% |

| Note: British Punjab province era district borders are not an exact match in the present-day due to various bifurcations to district borders — which since created new districts — throughout the historic Punjab Province region during the post-independence era that have taken into account population increases. | ||||||||||

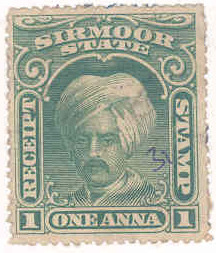

Artwork

[edit]

Not many paintings depicting the historical rajas of Sirmur State have survived due to the Gurkha occupation of the state between 1803 and 1814, which led to the loss and destruction of much artwork, including any portraits of earlier rulers produced in Sirmur itself.[14][15]

Notes

[edit]- ^ 1931-1941: Including Ad-Dharmis

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Singh, Mian Goverdhan (1999). Wooden Temples of Himachal Pradesh. Indus Publishing. pp. 48–49. ISBN 9788173870941.

- ^ Panikkar, Ayyappa (1997). Medieval Indian Literature: Surveys and selections. Sahitya Akademi. p. 72. ISBN 978-81-260-0365-5.

- ^ a b Sen Negi, Thakur (1969). Himachal Pradesh District Gazetteers: Sirmur. Government of Himachal Pradesh. pp. 52–54.

- ^ Sen Negi, Thakur (1969). Himachal Pradesh District Gazetteers: Sirmur. Government of Himachal Pradesh. pp. 55–57.

- ^ a b c Archer, William George (1973). Indian Paintings from the Punjab Hills. Indian Paintings from the Punjab Hills: A Survey and History of Pahari Miniature Painting. Vol. 1. Sotheby Parke Bernet. p. 414. ISBN 9780856670022.

- ^ Archives, Royal (26 July 2025). "Sirmur (Princely State)". Royal Archives. Retrieved 26 July 2025.

- ^ "9-year-old Jaipur prince becomes Maharaja of Sirmaur". India Today. 15 May 2013. Retrieved 26 July 2025.

- ^ "Census of India 1901. [Vol. 17A]. Imperial tables, I–VIII, X–XV, XVII and XVIII for the Punjab, with the native states under the political control of the Punjab Government, and for the North-west Frontier Province". 1901. p. 34. JSTOR saoa.crl.25363739. Retrieved 30 March 2024.

- ^ "Census of India 1911. Vol. 14, Punjab. Pt. 2, Tables". 1911. p. 27. JSTOR saoa.crl.25393788. Retrieved 30 March 2024.

- ^ Kaul, Harikishan (1911). "Census Of India 1911 Punjab Vol XIV Part II". p. 27. Retrieved 30 March 2024.

- ^ "Census of India 1921. Vol. 15, Punjab and Delhi. Pt. 2, Tables". 1921. p. 29. JSTOR saoa.crl.25430165. Retrieved 30 March 2024.

- ^ "Census of India 1931. Vol. 17, Punjab. Pt. 2, Tables". 1931. p. 277. JSTOR saoa.crl.25793242. Retrieved 30 March 2024.

- ^ "Census of India, 1941. Vol. 6, Punjab". 1941. p. 42. JSTOR saoa.crl.28215541. Retrieved 30 March 2024.

- ^ Plumbly, Sara (2020). "RAJA JAGAT PRAKASH OF SIRMUR (R.1770-89) WORSHIPPING RAMA AND SITA". Christie's. Retrieved 23 October 2024.

Very few portraits of Sirmur rulers remain as the Gurkha occupation of the state in 1803-14 is thought to have destroyed any earlier paintings.

- ^ Galloway, Francesca. Pahari Paintings From the Eva and Konrad Seitz Collection (PDF). www.francescagalloway.com. p. 48.

Further reading

[edit]- Singh, Kanwar Ranjhor (1912). Tarikh-i-Riyasat Sirmaur [History of Sirmaur State] (in Persian).

Sirmur State

View on GrokipediaHistory

Legendary and Early Origins

The early history of Sirmur State is intertwined with local legends, lacking firm archaeological or documentary corroboration beyond oral traditions preserved in state gazetteers and chronicles. One prominent legend recounts the reign of Raja Madan Singh, dated to approximately 1132 AD (Vikram Samvat 1189), during which a woman proficient in necromancy appeared at court and demonstrated her abilities by crossing the Giri River on a taut rope between the villages of Toka and Poka.[1][7] Skeptical of her powers, Madan Singh's courtiers severed the rope, causing her to drown; this act allegedly triggered a catastrophic flood that obliterated the capital and extinguished the ruling line, leaving the state without a sovereign.[1][8] In the ensuing power vacuum, the state's subjects reportedly petitioned the Raja of Jaisalmer—a Bhati Rajput ruler—for a successor, who dispatched his son Soba Rawal (also known as Raja Subans Prakash) around 1095–1097 AD to assume the throne and establish the Prakash dynasty.[1][9] Soba Rawal fixed the initial capital at Rajban, reigning briefly until 1099 AD, after which his descendants continued the line, marking the conventional founding of the state as a distinct entity.[9] This narrative aligns with broader traditions linking Sirmur's rulers to Rajput migrations from Rajasthan, though variants attribute the foundation directly to a figure named Raja Rasalu (or Rasaloo), a semi-legendary prince associated with Jaisalmer's Salvahan lineage, potentially conflating familial ties such as a brother named Buland whose son bore the name Sirmur.[10][9] The etymology of "Sirmur" (or Sirmaur) reflects these mythic origins, possibly deriving from "Shiromorya," denoting a king honored by the Mauryan emperor Chandragupta, or "Ser-Mour," implying a palace beside a sacred pond like the Sirmouri Taal near Paonta Sahib, which some traditions identify as an ancient Kulind capital site.[9] Earlier inhabitants are traced to the Kunindas, an ancient Indo-Aryan tribe mentioned in Ashokan edicts, with the region's prior name recorded as Surughna in classical texts, suggesting continuity from pre-medieval hill polities rather than wholesale invention.[11] These accounts, while evocative, rely on princely chronicles prone to dynastic glorification and lack independent verification, underscoring the hazy boundary between legend and historical inception.[1]Founding of the State and Early Rajas

The origins of Sirmur State, initially known as Nahan, are rooted in the late 11th century following a flood that eradicated the prior ruling family under Raja Madan Singh.[1] Local nobles appealed to the Bhati Rajput rulers of Jaisalmer for a successor, prompting Raja Ugar Sen to send his son Soba Rawal, who founded the kingdom at Rajban and adopted the regnal title Subans Prakash circa 1097 AD.[1] This event established the Prakash dynasty, with rulers appending "Prakash" to their names, marking the conventional founding date of the state around 1095 AD in traditional accounts.[2] Early rajas focused on territorial consolidation and capital shifts amid the rugged Shivalik Hills. Malhi Prakash (r. 1108–1117 AD) exemplified religious piety and philanthropy, successfully conquering Malda fort to expand influence.[1] His successor, Udit Prakash (r. 1121–1127 AD), relocated the capital to Kalsi for strategic advantages.[1] Somar Prakash (r. 1149–1158 AD) further secured the realm by capturing Ratesh fort and designating it as the new capital.[1] Suraj Prakash (r. 1158–1169 AD) reversed this by restoring Kalsi as capital while quelling internal rebellions.[1] These initial rulers navigated a landscape of local chieftaincies and environmental hazards, laying foundations for dynastic continuity through military and administrative measures, though records remain sparse and blend legend with chronicle.[1] The Prakash line persisted, transitioning toward greater centralization by the 16th century as external powers like the Mughals loomed.[2]Establishment of Nahan as Capital

Nahan was founded as the new capital of the Sirmaur State in 1621 by Raja Karam Prakash, who reigned from 1616 to 1630.[1] Prior to this, the state's capital had shifted between locations such as Neri, Kot, and Gargah in the Ratesh Pargana, with later moves including to Kalsi near Dehradun during the rule of Raja Budh Prakash.[1] Karam Prakash, influenced by his spiritual guide Baba Banwari Das, selected the site where the saint had resided, establishing it as a permanent seat of power to consolidate administration in a more defensible and central location.[1] The establishment involved the construction of a fort in Nahan, marking a significant development that stabilized the state's governance amid earlier instability from shifting capitals.[9] This move also coincided with the renaming of the state to Sirmur, reflecting the new capital's prominence, and transitioned the polity from its predecessor Nahan State origins dating back to 1095 under Raja Subans Prakash.[2] The fort's building symbolized military strengthening, aiding the raja's efforts to colonize nearby tracts like Kiaradun, previously dense forests.[1]Relations with Mughals and Sikhs

Raja Dharam Prakash of Sirmur, reigning during the time of Mughal Emperor Akbar, maintained tributary relations with the Mughal Empire, as did other Himalayan states that acknowledged imperial suzerainty through periodic tribute payments.[12] In 1636, under Raja Mandhata Prakash, Sirmur forces joined a Mughal expedition against Garhwal, regaining control of the strategic pargana of Kalsi despite the campaign's overall failure.[8] During the reign of Budh Prakash (1664–1684), Mughal imperial forces, led by a prince, transferred the forts of Bairat and Kalsi from the Raja of Srinagar (Garhwal) to Sirmur control, reinforcing alliances through territorial grants.[1] Subhag Prakash, a later ruler, provided military assistance to Emperor Shah Jahan in conquering Srinagar (in Garhwal), earning a royal firmaan and the annexation of the Kotaha region to Sirmur territories as reward for these services.[11] Sirmur rajas continued aiding Mughal campaigns against regional rivals for over a century, expanding their domain while supplying resources such as ice from the hills to the imperial court, navigating the treacherous terrain to sustain Mughal logistics.[13] These interactions positioned Sirmur as a loyal vassal, benefiting from imperial favor amid competition with neighboring hill states like Garhwal and Kangra.[6] Relations with Sikh powers began with alliance-building in the late 17th century. Raja Medini Prakash (also known as Mat or Mit Prakash) invited Guru Gobind Singh to Sirmur territory in 1685, granting land at Paonta Sahib on the Yamuna River for fortification and residence, seeking Sikh military support against Mughal pressures and rival hill rajas.[14] The Guru established a base there, forging ties that included mediating friendship between Medini Prakash and the Raja of Garhwal, though tensions arose during the Battle of Bhangani in 1688, where Guru Gobind Singh faced a coalition of hill rulers.[15] By the early 18th century, conflicts emerged; in 1710, Raja Kirat Prakash defeated the Raja of Garhwal and seized territories including Naraingarh, Morni, and Pinjaur from Sikh control, formalizing gains through a treaty.[9] As Sikh misls rose, Sirmur paid an annual tribute of 2,000 rupees to the Bhangi Sardars of Buria until 1809, reflecting subjugation to Sikh military dominance in the Cis-Sutlej region before British intervention shifted dynamics.[16] These interactions evolved from strategic hospitality toward the Sikh Gurus to tributary obligations and occasional territorial assertions against Sikh expansions, amid the broader power vacuum following Mughal decline.[9]Gurkha Invasion and British Restoration

In the early 19th century, Sirmur State faced internal instability under Raja Karam Prakash II (r. 1793–1815), an inexperienced ruler who encountered challenges from neighboring Hindur and a rebellion by his brother Kanwar Ratan Singh, supported by local officers. Amid rumors of his death and displacement, Karam Prakash sought military aid from the expanding Gurkha kingdom of Nepal, leading to their intervention. In 1803, Gurkha forces under Kazi Ranjor Thapa invaded Sirmur, defeating Ratan Singh's faction and capturing the capital at Nahan, though they subsequently occupied the territory rather than fully restoring the raja.[4][17] The Gurkha occupation, which endured from 1803 to 1815, involved fortifying strategic sites such as Nahan and Jaitak fort, while Karam Prakash took refuge in British-held Bhuria near Ambala. Gurkha commander Ranzor Singh, son of Amar Singh Thapa, enforced control over the hill state as part of broader Nepalese expansion into the Himalayan regions, including Kumaon, Garhwal, and other Punjab Hill States. This period disrupted local governance and artwork preservation, with Gurkha depredations contributing to the loss of historical portraits of Sirmur rulers.[17][18] The occupation ended during the Anglo-Nepalese War (1 November 1814 – 4 March 1816), when British East India Company forces, led by David Ochterlony, advanced against Gurkha positions in the hills. British victories, including the capture of key forts, compelled Gurkha withdrawal from Sirmur by 1815. Under the Treaty of Sugauli (signed 2 November 1815, ratified 1816), Nepal ceded territories west of the Kali River, enabling the British to restore Karam Prakash II as ruler while establishing Sirmur as a protected princely state obligated to pay tribute and align with British foreign policy.[17][4]British Protectorate and Internal Developments

Following the Anglo-Nepalese War, the Gurkhas evacuated Sirmur in 1815 pursuant to the Treaty of Sugauli, establishing the state as a British protectorate. The British granted a sanad to Fateh Prakash, the infant son of the exiled Raja Karam Prakash, with his grandmother Rani Ausmat Kaur (Goler Rani) serving as regent until he assumed full powers in 1827. In 1833, the British restored the Kiarda Dun tract to Sirmur for a payment of Rs. 50,000, bolstering the state's territory. Fateh Prakash supported the British during the First Anglo-Sikh War (1839-1846), receiving territorial concessions in return.[1] Under subsequent rulers, Sirmur maintained loyalty to the British, aiding suppression of the 1857 Indian Rebellion under Raja Shamsher Prakash, who was rewarded with the title of Raja-i-Rajagan and a perpetual salute of 11 guns. Shamsher Prakash (r. 1856-1898) initiated administrative modernization, establishing formal courts of justice, a police force, and revenue systems modeled on British India practices. He founded schools in Nahan and other towns, developed the Nahan Foundry for local manufacturing, and promoted colonization of the Kiarda Dun valley for agriculture, enhancing economic productivity.[1] Raja Surendra Bikram Prakash (r. 1898-1911) continued these efforts by reorganizing judicial courts, integrating the state's postal service with the imperial system, inaugurating the Surendra Water Works for Nahan's supply, and implementing anti-corruption measures to curb bribery in administration. He also contributed 20,000 pounds of tea to British forces during the Second Boer War, reflecting sustained allegiance. His successor, Amar Prakash (r. 1911-1933), expanded education with additional schools, constructed roads such as the Nahan-Kala Amb route in 1927, and conducted a comprehensive land settlement in 1931 to improve revenue assessment accuracy and tenant rights. These reforms fostered gradual infrastructure growth and administrative efficiency within the protectorate framework, while preserving internal autonomy under British paramountcy.[1]Accession to India

Following the lapse of British paramountcy on 15 August 1947, Sirmaur State, ruled by Maharaja Rajendra Prakash Bahadur since 1933, encountered significant internal challenges that influenced its path to integration with the Dominion of India.[19] The Pajhota Andolan, a peasant uprising in the Pajhota region beginning around 1942, protested against oppressive taxation, begar (forced labor), and feudal land systems, escalating into widespread unrest by 1947-1948.[20] This movement, supported by the Sirmaur State Praja Mandal formed to advocate for representative government, led to the imprisonment of key leaders and temporary suppression by state forces, creating pressure for political change amid the broader context of princely state accessions.[21] [20] Maharaja Rajendra Prakash, initially resistant to full integration to preserve monarchical authority, ultimately signed the Instrument of Accession on 23 March 1948, ceding control over defense, external affairs, and communications to the Indian government while retaining internal autonomy.[9] [22] Concurrent with the accession, leaders of the Pajhota movement were released from prison, signaling a concession to reformist demands.[20] This document formalized Sirmaur's entry into the Indian Union, aligning with the integration of over 500 princely states, though smaller hill states like Sirmaur often acceded later due to local dynamics.[9] Subsequently, on 15 April 1948, Sirmaur merged into the newly constituted Chief Commissioner's Province of Himachal Pradesh, comprising 30 former princely states including Chamba, Mandi, and Bilaspur, thereby dissolving its independent administration and incorporating its approximately 4,039 square kilometers of territory into the provincial structure.[11] The merger, executed via an Instrument of Merger signed earlier on 13 March 1948, faced initial legal challenges from the former ruler but was upheld, marking the end of the Prakash dynasty's sovereign rule.[11] Rajendra Prakash received a privy purse of 75,000 rupees annually until the abolition of such privileges in 1971, reflecting India's policy of privy purses for ex-rulers as compensation for lost revenues.[6]Geography

Territorial Extent and Borders

Sirmur State encompassed approximately 4,039 square kilometres (1,559 square miles) of territory in the foothills of the Himalayas, primarily within the Shivalik range, as recorded in the 1901 Census of India.[23] This area included rugged mountainous terrain interspersed with valleys, supporting a population of 135,626 inhabitants at that time.[23] The state's extent was shaped by natural features such as the Yamuna River, which formed part of its eastern and northern boundaries, and the Giri River to the west.[24] The borders of Sirmur were defined by a combination of natural barriers and political delimitations with neighboring entities. To the south and west, it adjoined British-administered territories in the Ambala Division, facilitating trade and administrative interactions while marking the transition to the Punjab plains.[6] On the north, the state shared frontiers with the princely states of Jubbal and Bashahr (Bushahr), regions with which it experienced occasional boundary disputes, particularly over frontier posts like Paonta Sahib.[25] The eastern boundary followed the Tons River, separating Sirmur from the Garhwal region, historically under Gurkha influence before British intervention in the early 19th century.[9] These borders remained relatively stable under British paramountcy from 1815 onward, though minor adjustments occurred due to treaties and surveys.[26]Physical Features and Resources

Sirmur State occupied a predominantly hilly and rugged terrain in the lower Himalayan region, specifically within the Shivalik Hills, encompassing both Cis-Giri and Trans-Giri areas divided by the Giri River.[27] [9] Altitudes in the state ranged from about 450 meters to 2,500 meters above sea level, with the landscape featuring flat-bottomed valleys known as duns, such as Kayar-da-Dun.[28] [27] The highest elevation was Churdhar Peak (also called Choor Chandni), at 3,647 meters, situated in the Shivalik range and serving as the tallest point in southern Himachal Pradesh.[29] [25] Principal rivers included the Yamuna, which demarcated the southern boundary, along with tributaries such as the Tons, Giri, Ponda, and Bata; the Giri notably cuts through the central district before joining the Yamuna near Paonta Sahib.[28] [27] [30] Dense forests covered much of the hilly expanses, supporting a landscape of emerald valleys and contributing to biodiversity, while minor mineral resources like sandstone, bajri, and stone were present for extraction.[31] [32]Rulers

The Prakash Dynasty

The Prakash Dynasty, which ruled Sirmur State for over eight centuries, originated around 1095 when a Bhati Rajput named Plasoo succeeded to the local throne of Surkhot and assumed full powers as Raja Shubhans Prakash, establishing the new dynastic line.[4] Traditional accounts trace the dynasty's ancestry to Rajput clans from Jaisalmer in Rajasthan, with early rulers maintaining control over the hilly terrain amidst shifting regional powers.[11] The adoption of the "Prakash" epithet by successive rulers symbolized their claimed solar lineage and became a hallmark of the dynasty's identity.[33] Throughout its tenure, the dynasty practiced hereditary male primogeniture, ensuring stable succession despite external threats, with rulers navigating Mughal overlordship in the 17th-18th centuries by providing military aid and tribute.[33] Key early figures included Raja Karam Prakash I (r. 1616-1630), who founded Nahan as the state capital in 1621, solidifying administrative centralization, and Raja Mandhata Prakash (r. 1630-1654), who expanded influence through diplomatic marriages and territorial consolidation.[33] The dynasty's resilience was tested during the Gurkha invasion of 1803-1815, after which British restoration in 1815 placed Sirmur under protectorate status, yet allowed internal autonomy under rulers like Fateh Prakash (r. 1815-1850).[1] In the 19th century, Raja Shamsher Prakash (r. 1856-1883) introduced administrative reforms, including revenue settlements and infrastructure improvements, fostering economic stability while adhering to British alliances.[34] The dynasty patronized Pahari painting schools, as evidenced by portraits depicting rulers in courtly and devotional scenes, reflecting cultural continuity amid political changes.[33] By the early 20th century, Maharaja Rajendra Prakash (r. 1933-1948) oversaw modernization efforts before acceding to the Indian Union on 15 August 1948, marking the end of sovereign rule while preserving the lineage's historical legacy.[35] The dynasty's endurance stemmed from adaptive governance, strategic foreign relations, and exploitation of the state's forested and agricultural resources for revenue.[1]Succession and List of Rajas

Succession in Sirmur State adhered to male primogeniture, with the throne passing to the eldest legitimate son upon the Raja's death. Where direct male heirs were absent, the incumbent Raja held the authority to adopt a male successor from collateral branches of the Prakash family, ensuring dynastic continuity without external interference. This system, rooted in customary Hindu law as applied in princely states, was upheld through the British protectorate period and into independence, though post-1947 titular successions occasionally involved family disputes resolved by consensus or adoption.[4][33] The Prakash dynasty, claiming descent from 11th-century origins, produced a lineage of Rajas who governed Sirmur from its consolidation as a distinct state. Reign dates for earlier rulers remain approximate due to reliance on bardic chronicles and limited archival records, while later ones align with British-era documentation. The following table lists the Rajas from the 17th century onward, when the state achieved greater historical clarity under Mughal suzerainty:| Raja | Reign Period |

|---|---|

| Karam Prakash I | 1616–1630 |

| Mandhata Prakash | 1630–1654 |

| Sobhag Prakash | 1654–1664 |

| Budh Prakash | 1664–1684 |

| Mat Prakash | 1684–1704 |

| Hari Prakash | 1704–1712 |

| Bijay Prakash | 1712–1736 |

| Pratap Prakash | 1736–1754 |

| Kirat Prakash | 1754–1770 |

| Jagat Prakash | 1770–1789 |

| Dharam Prakash | 1789–1793 |

| Karam Prakash II | 1793–1803, 1804–1815 |

| Ratan Prakash | 1803–1804 |

| Fateh Prakash | 1815–1850 |

| Raghbir Prakash | 1850–1856 |

| Shamsher Prakash | 1856–1898 |

| Surendra Bikram Prakash | 1898–1911 |

| Amar Prakash | 1911–1933 |

| Rajendra Prakash | 1933–1948 (ruling until accession) |