Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

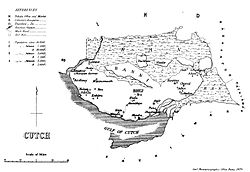

Cutch State

View on Wikipedia

Cutch State, also spelled Kutch or Kachchh and also historically known as the Kingdom of Kutch, was a kingdom in the Kutch region from 1147 to 1819 and a princely state under British rule from 1819 to 1947. Its territories covered the present day Kutch region of Gujarat north of the Gulf of Kutch. Bordered by Sindh in the north, Cutch State was one of the few princely states with a coastline.

Key Information

The state had an area of 7,616 square miles (19,725 km2) and a population estimated at 488,022 in 1901.[1] During the British Raj, the state was part of the Cutch Agency and later the Western India States Agency within the Bombay Presidency. The rulers maintained an army of 354 cavalry, 1,412 infantry and 164 guns.[citation needed]

History

[edit]

A predecessor state known as the Kingdom of Kutch was founded around 1147 by Lakho Jadani of the Samma tribe who had arrived from Sindh. He was adopted by Jam Jada and hence known as Lakho Jadani. He ruled Eastern Cutch from 1147 to 1175 from a new capital, which he named Lakhiarviro (near present-day Nakhatrana) after his twin brother Lakhiar.[citation needed] Prior to this time, Eastern Cutch was ruled by the Chawda dynasty, whose last noted ruler was Vagham Chawda, who was killed in the 9th century by his nephews Mod and Manai, who later assumed power of his territories and established the first Samma Dynasty of Kutch.[2] At the same time, Central and Western Kutch were under the control of different tribes such as the Kathi, Chaulukya and Waghela.[2] After the death of Raydhan Ratto in 1215 his territories were divided between his four sons. Othaji, Dedaji, Hothiji and Gajanji and they were given the Kutch territories of Lakhirviro, Kanthkot, Gajod and Bara respectively.

As Othaji was the eldest he ascended to the head throne of Lakhirviro and the rest became a part of Bhayyat or the Brotherhood in a federal system of government. However, internal rivalry between them escalated over the generations and until they merged into the two groups of Othaji and Gajanji of Bara. The first incident among the rivals which changed the history of Kutch was the murder of Jam Hamirji of Lakhiarviro, chief of the eldest branch of the Jadejas and descendant of Othaji, by Jam Rawal of Bara. It is believed that Jam Rawal attributed the murder of his father Jam Lakhaji to Hamirji, as he was killed within the territory of Lakhiarviro by Deda Tamiachi at the instigation of Hamirji.[3] Jam Rawal, in revenge treacherously killed his elder brother Rao Hamirji, (father of Khengarji) and ruled Cutch for more than two decades till Khenagrji I, reconquered Cutch from him, when he grew up. Jam Rawal escaped out of Cutch and founded the Nawanagar as per advice given by Ashapura Mata in a dream to him.[3] Later his descendants branched out to form the state of Rajkot, Gondal Dhrol and Virpur.[4] The Genealogy is still maintained today, by the Barots of respective Jadeja branches and every single person in Jadeja clan can trace their ancestry through to Rato Rayadhan.[4]

Lakhiarviro remained the capital of Cutch from its foundation in 1147 until the time of Jam Raval in 1548.

Rulers

[edit]

Cutch was ruled by the Jadeja Rajput dynasty of the Samma tribe[1] from its formation in 1147 until 1948 when it acceded to newly formed India. The rulers had migrated from Sindh into Kutch in late 12th century. They were entitled to a 17-gun salute by the British authorities. The title of rulers was earlier Ja'am, which during British Raj changed to Maharao made hereditary from 1 Jan 1918.[5]

Khengarji I, is noted as the founder of Cutch State, who united Eastern Central and Western Cutch into one dominion, which before him was ruled partially by other Rajput tribes like Chawda and Solanki dynasty,[6] apart from the Jadejas.[1] Khenagarji I was given fiefdom of Morbi and an army by Sultan Mahmud Begada of Ahmedabad, whose life he had saved from a lion. Khengarji waged a war for several years till he re-conquered Cutch from Jam Raval and integrated Cutch into one large dominion in 1549. Jam Raval had to escape out of Cutch to save his life. Khengarji I was able to capture his father's past capital Lakhiarviro and Jam Raval's capital Bara, and formally ascended throne at Rapar in year 1534[7] but later shifted his capital to Bhuj.[1] Khengarji also founded the port city of Mandvi.

After the demise of Rayadhan II in 1698, the regularity of succession was again deviated, Raydhunji had three sons, Ravaji, Nagulji and Pragji.Ravaji the eldest son was murdered by Sodha Rajputs, his second brother Nagulji had died of natural causes before, both the brothers, however had left sons, who by right were entitled to succeed the throne of Kutch, but as they were young, Pragji, the third son of Rao Raydhunji eventually usurped the throne of Cutch and became Maharao Pragmulji I.[8]

Kanyoji, the eldest son of murdered Ravaji escaped and established himself at Morbi, which before that formed part of Kingdom of Kutch. Kanyoji made Morvi independent of Cutch and from there he tried unsuccessfully many a times to regain his rightful throne of Cutch. The descendants of Kanyoji Jadeja thus settled in Morvi and were called Kaynani.[1]

Bhuj was later fortified by Bhujia Fort under reign of Rao Godji I (1715–19). The major work and completion of fort was done during the rule of his son, Maharao Deshalji I (1718–1741). In 1719 during reign of Deshalji I, Khan, who was Mughal Viceroy of Gujarat invaded Kutch. The army of Kutch was in a precarious condition, when a group of Naga Bawas joined them and Mughal army was defeated.

Deshalji was succeeded by his son Rao Lakhpatji (1741–61), who appointed Ram Singh Malam, to build the famous Aina Mahal. Ram Singh Malam also started a glass and ceramic factory near Madhapar. During reign of Lakhpatji maritime business of Cutch flourished and it was during his regime,Cutch issued its own currency, Kutch kori, which remained valid even during British Raj till 1948, when they were abolished by independent India.

Later, during the rule of Rao Godji II (1761–1778), the state faced its biggest defeat at hands of Mian Ghulam Shah Kalhoro of Sindh, who attacked Cutch twice once in 1763–64, (when hundreds of Kutchi people died in the battle near Jara, Kutch) and again in 1765. Godji had to make a truce with him after losing several territories. Later in 1770, a daughter of his cousin Wesuji was married to the Mian Kalhoro and the marriage was celebrated with great pomp and splendor on both the sides. In consideration of this relationship, the towns of Busta Bandar and Lakhpat and others territories that had been conquered by the Mián Kalhoro, were returned to the Rao of Cutch.

His successor, Rayadhan III (1778–86) became a religious fanatic and began forcibly converting all its pupils to Islam. At that time Raydhan was curtailed when in 1785, Anjar's Meghji Seth lead the revolt and the local chief of armies Dosal Ven and Fateh Muhamad also joined him in the coup.[9] Raydhan was put under house arrest and the state was ruled under a council of the twelve members, Bar Bhayat ni Jamat, under minor titular king, Prithvirajji. Fateh Muhammad was made ruler by these council who ably ruled Cutch from 1786 to 1813. After his death Rao Raydhan was again made a king by the council for a month but was replaced by Husain Miyan, as Rao had still not changed his ways. Husain Miyan ruled from 1813 to 1814 and later Bharmalji II, eldest son of Raydhan was made ruler in 1814 by the council keeping the army under control of Husain Miyan.[9]

On 15 December 1815, the army of Cutch state was defeated near Bhadreswar, Kutch by the combined armies of British and Gaekwads of Baroda State. The nearest major fortified town of Anjar, Port of Tuna and district of Anjar thus came under British occupation on 25 December 1815. This led to negotiations between rulers of Kutch and British. The Jadeja rulers of Kutch accepted the suzerainty of British in 1819 and Captain James MacMurdo was posted as British Political Resident stationed at Bhuj. The Anjar District, however, remained under direct occupation of British forces for seven years till 25 December 1822, when it was territory reverted to Cutch by an agreement.[1][10]

After the victory the British deposed the ruling king Jam Bharmulji II and his son Deshalji II, a minor was made the ruler of Cutch State. During his minority the affairs of the State were managed by Council of Regency, which was composed of Jadeja chiefs and headed by Captain MacMurdo.[11][12][13]

During his reign Kutch suffered a severe earthquake in 1819 followed by severe famine in 1823, 1825 and 1832.[citation needed] Further, Kutch was attacked by marauding band from Sindh.[citation needed] Deshalji II although 18 years of age took the management of law in his own hands and defeated aggressor from Sindh. His reign saw maritime trade with Africa, Oman and especially Zanzibar improve significantly. Slowly and steadily the industrialisation in Cutch got a set back which was started by Lakhpatji and Godji.[14] He was succeeded by his son Pragmalji II in 1860.

During later half of the 19th century and first half of the 20th century state progressed under leadership of Pragmalji II and his successor Khengarji III. The educational, judiciary and administrative reforms, which were started by Pragmulji II, were carried further by Khengarji III, who also laid foundation of Cutch State Railway, Kandla port and many schools. Khengarji III was the longest ruling king of Cutch. Khengarji also served as Aide-De-Campe to Queen Victoria for some years. Under him state was elevated to status of 17-gun salute state and title of rulers of Cutch also was elevated as Maharao.[citation needed]

Khengarji III was succeeded by his son Vijayaraji in 1942 and ruled for a few years until India became independent. During the reign of Vijayaraji the Kutch High Court was instituted, village councils were elected and irrigation facilities were expanded greatly and agricultural development in the state during short span of six years of his rule. He took keen interest in irrigation matters and it was during his reign the Vijaysagar reservoir was built together with another 22 dams.[15] Cutch became the third princely state after Hyderabad and Travancore to start its own bus transport services beginning in year 1945.[16] Additionally, a set of specimen banknotes was printed for the state of Cutch in 1946, but was never put into production.

Cutch was one of the first princely states to accede to India upon its independence on 15 August 1947. Vijayraji was away for medical treatment at London. Upon his order Madansinhji, on behalf of his father, signed the Instrument of Accession of Kutch, on 16 August 1947, in his capacity as attorney of Maharao of Kutch.[17] Later, Madansinhji acceded the throne, upon death of his father Vijayaraji on 26 January 1948 and became the last Maharao of Cutch, for a short period of time till 4 May 1948, when the administration of the state was completely merged in to the Union of India.

The princely State of Cutch upon merger into India, was made a separate centrally administered Class-C state by the name Kutch State in 1948.

List of rulers

[edit]| Rulers regional name | Accession year (CE) |

|---|---|

| Lakho Jadani | 1147–1175 |

| Ratto Rayadhan | 1175–1215 |

| Othaji | 1215–1255 |

| Rao Gaoji | 1255–1285 |

| Rao Vehanji | 1285–1321 |

| Rao Mulvaji | 1321–1347 |

| Rao Kaiyaji | 1347–1386 |

| Rao Amarji | 1386–1429 |

| Rao Bhhemji | 1429–1472 |

| Rao Hamirji | 1472–1536 |

| Jam Raval | 1540–1548 |

| Khengarji I | 1548–1585 |

| Bharmalji I | 1585–1631 |

| Bhojrajji | 1631–1645 |

| Khengarji II | 1645–1654 |

| Tamachi | 1654–1665 |

| Rayadhan II | 1665–1698 |

| Pragmalji I | 1698–1715 |

| Godji I | 1715–1719 |

| Deshalji I | 1719–1741 |

| Lakhpatji (regent) | 1741–1752 |

| Lakhpatji | 1752–1760 |

| Godji II | 1760–1778 |

| Rayadhan III (1st time) | 1778–1786 |

| Prithvirajji | 1786–1801 |

| Fateh Muhammad (regent) | 1801–1813 |

| Rayadhan III (2nd time) | 1813 |

| Husain Miyan (regent) | 1813–1814 |

| Bharmalji II | 1814–1819 |

| Deshalji II | 1819–1860 |

| Pragmalji II | 1860–1875 |

| Khengarji III | 1875–1942 |

| Vijayaraji | 1942–1948 |

| Madansinhji | 1948 |

Titular Maharaos

[edit]- Madansinhji — 1948–1991

- Pragmulji III — 1991–2021

- Hanvantsinji — since 2021

Religion

[edit]The Jadejas were followers of Hinduism and worshiped Ashapura Mata, who is the kuldevi of Jadeja clan and also the State deity. The main temple of goddess is located at Mata no Madh.

Demographics and economy

[edit]There were eight main towns in the State − Bhuj, Mandvi, Anjar, Mundra, Naliya, Jakhau, Bhachau and Rapar and 937 villages.[1] Apart from it there were other port towns of Tuna, Lakhpat, Sandhan, Sindri, Bhadresar on its coastline, which boosted the maritime trade, the main revenue earner of State. There are also other towns like Roha, Virani Moti, Devpur, Tera, Kothara, Bara, Kanthkot, which were overlooked by Bhayaat (brothers) of the Kings as their jagirs.

The various Kutchi community were known for their trades with Muscat, Mombasa, Mzizima, Zanzibar, and others, and also for their shipbuilding skills. Kandla was developed by Khengarji III in 1930 as a new port. Cutch State Railway was also laid during his reign, during the years 1900–1908, which connected main towns like Bhuj, Anjar, Bachau to the ports of Tuna and Kandla. The railways enhanced business a lot as it paved the way for movement of goods and passengers.

Hindus numbered around 300,000, Mohammedans around 110,000 and Jains were 70,000 in population as per 1901 census.[1] About 9% of population were Rajputs and Brahmins & other Hindu caste formed another 24% of population of State.[1] The most common language spoken was Kutchi language and Gujarati language. Gujarati was the language used in writings and courts & documents.[1]

Agriculture was the main occupation of people, who take produce of wheat, Jowar, Bajra, Barley, etc. apart from cattle raising being the other main occupation.[1]

Currency

[edit]The currency of Kutch state was known as 'kori', a silver coin of 4.6 grams. The kori was subdivided into smaller units, such as the adhiyo (1/2 kori), payalo (1/4 kori), dhabu (1/8 kori), dhinglo (1/16 kori), dokdo (1/24 kori) and trambiyo (1/48 kori). Higher denominations included silver coins of 2.5 kori and 5 kori, and gold coins of 25 kori, 50 kori and 100 kori. Coins of Kutch state traditionally carried the name of the local ruler on one side, and the British rulers on the other side (from 1858 onward). The last coins of Kutch, minted in 1947 (V.S. 2004), at the time of kingdom's merger with India, replaced the British monarch with the words Jai Hind.

Rulers and chiefs gallery

[edit]- Maharaos of Cutch

-

Lakhpatji : r - 1741–1760.

-

Deshalji II : r -1819-1860.

-

Pragmalji II : r-1860-1875.

-

Khengarji III : r-1875-1942.

-

Pragmulji III : titular Maharao from 1991 to 2021

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Cutch". The Imperial Gazetteer of India. 11: 75–80. 1908.

- ^ a b Panhwar, M.H. (1983). Chronological Dictionary Of Sind. Jamshoro: Institute of Sindhlogy, University of Sind. pp. 170–171.

The eldest son Unar born of Gaud Rani succeeded him but was murdered by his step brothers Mod and Manai. Gaud Rani managed the succession of her grandson and therefore Mod and Manai escaped to Cutch with a few followers and took refuge with their Chawra maternal uncle at Patogh (6 miles West of Lakhpat, now in ruins). Finding an opportunity they killed him and seized his city and surrounding territories with the help of their clansmen from Sind. They then subdued Guntn, which was ruled by Vaghelas. Finally they annexed Anahilapataka

- ^ a b The Land of 'Ranji' and 'Duleep', by Charles A. Kincaid by Charles Augustus Kincaid. William Blackwood & Sons, Limited. 1931. pp. 11–15.

- ^ a b The Paramount Power and the Princely States of India, 1858–1881 – Page 287

- ^ Princely states of India: a guide to chronology and rulers – Page 54

- ^ Katariya, Adesh (2007). Ancient History of Central Asia: Yuezhi origin Royal Peoples: Kushana, Huna, Gurjar and Khazar Kingdoms. Adesh Katariya. p. 348. Retrieved 10 November 2017.

- ^ Tyabji, Azhar (2006). Bhuj: Art, Architecture, History. Mapin. p. 267. ISBN 9781890206802. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

- ^ Gujarat State Gazetteer – Volume 1 – pp. 275–276

- ^ a b Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency: Cutch, Pálanpur, and Mahi Kántha – Page 149

- ^ "Glimpse of Anjar, Kutch". Archived from the original on 8 June 2011. Retrieved 13 May 2013.

- ^ Tyabji, Azhar (2006). Bhuj: Art, Architecture, History. Mapin. ISBN 978-1-890206-80-2.

- ^ Jadeja Rulers of Kutch : Deshalji II (1814–1860) Archived 13 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Kutch State : Maharao DESALJI BHARMALJI II (Daishalji) 1819/1860 Archived 5 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ The presence of a glass factory and good breed of horses led Maharao Deshalji II (1819–1960) to maritime long distance trade with Zanzibar and most of all with Sultan of Oman. Makran, Oman, and Zanzibar: three-terminal cultural corridor in the western By Beatrice Nicolini, Penelope-Jane Watson.

- ^ The Politics and Poetics of Water: The Naturalisation of Scarcity in Western ... By Lyla Mehta. 2005. pp. 87, 88.

- ^ State Transport Undertakings: Structure, Growth and Performance by P. Jagdish Gandhi – 1998– Page 37.|Hyderabad (1932) and Travancore (1938) which owned State enterprises, operated fleets of passenger buses. The small State of Kutch joined then in 1945.

- ^ Lauterpacht, E. (1976). International Law Reports: Volume 50. Butterworths. ISBN 978-0-406-87652-2.

Bibliography

[edit]- Burnes, James (1831). A Narrative of a Visit to the Court of Sinde [Sindh]; A Sketch of the History of Cutch, from its first connexion (sic) with the British Government in India till the conclusion of the treaty of 1819. Edinburgh: Robert Cadell; London:Whittaker, Treacher and Arnot.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 7 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 669–670.

External links

[edit] Media related to Cutch State at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Cutch State at Wikimedia Commons

Cutch State

View on GrokipediaGeography

Location and Borders

The Cutch State occupied a position in the northwestern extremity of the Indian subcontinent, centered on the Kutch peninsula and extending inland across arid plains and marshlands north of the Gulf of Kutch.[4] Its territory was delimited by the province of Sindh to the north and northeast, the Arabian Sea forming the southern and southwestern coastlines, and the adjacent Gujarat regions, including Kathiawar and other principalities, to the east and southeast.[4][5] The Rann of Kutch, a expansive seasonal salt marsh spanning thousands of square kilometers, constituted the primary northern frontier, functioning as a formidable natural impediment to incursions from Sindh while falling under Cutch's administrative jurisdiction.[6] This desolate expanse, intermittently inundated during monsoons, reinforced the state's isolation and defensive posture amid contested marshland claims.[5] Coastal features along the Gulf of Kutch conferred strategic maritime advantages, with ports like Mandvi serving as vital nodes in overland caravan routes across the desert and seafaring paths to the Persian Gulf.[7] Mandvi's location at the confluence of these trade corridors enabled commerce in commodities such as textiles and spices, bolstering economic ties despite the region's harsh environmental constraints.[8]Terrain and Natural Resources

The terrain of Cutch State consists primarily of arid desert landscapes and expansive saline flats, dominated by the Great Rann of Kutch in the north and the Little Rann of Kutch to the east, forming vast, flat mudflats that were historically part of the Arabian Sea before drying into salt-encrusted depressions. These regions feature low-lying elevations, often mere inches above sea level, interspersed with occasional hilly outcrops and grasslands like the Banni region, contributing to a topography shaped by tectonic forces and episodic flooding.[9][10] Climatic conditions are subtropical and semi-arid, marked by extreme summer heat exceeding 50°C, low annual rainfall, and monsoonal deluges from June to September that inundate the Rann, creating temporary wetlands amid persistent droughts. The area is seismically active, with the 16 June 1819 earthquake (estimated magnitude >7.5) generating the Allah Bund—a 90 km-long, 3-6 m high east-west ridge that uplifted over 1,000 km² of land, formed depressions prone to further inundation, and reshaped drainage patterns in the Great Rann.[11][12] Vegetation remains sparse and adapted to salinity and aridity, featuring thorny xerophytic shrubs, drought-resistant grasses, and sedges such as Cyperus and Scirpus species that emerge post-monsoon in moist patches. Natural resources encompass vast salt deposits in the Rann suitable for evaporation-based extraction, substantial limestone reserves comprising 67% of Gujarat's total (concentrated in formations like those in Lakhpat and Abdasa), and other minerals including lignite, bauxite, gypsum, and bentonite, as documented in regional geological assessments.[13][14][15][16]History

Pre-Jadeja Period and Origins

The region of Kutch exhibits evidence of early human settlement dating back to the Neolithic period, with archaeological findings indicating habitation as early as 7000 BCE, though these predate organized urban phases.[17] More substantively, Kutch formed a peripheral extension of the Indus Valley Civilization (IVC), with major sites like Dholavira revealing a Mature Harappan urban center active from approximately 2600 BCE to 1900 BCE, characterized by advanced water management systems, pottery, and trade artifacts linking it to core IVC regions in the Indus basin and beyond into Gujarat and Sindh.[18][19] These connections underscore Kutch's role in broader maritime and overland exchanges during the IVC's peak, facilitated by its coastal position and proximity to the Rann of Kutch, though the civilization's decline around 1900 BCE left the area sparsely populated amid aridification and shifting river courses, with limited continuity evidenced by post-Harappan pottery scatters.[20] Post-IVC, textual records of Kutch remain fragmentary until the medieval era, appearing peripherally in accounts of Gujarat-Sindh frontier dynamics rather than as a distinct polity; ancient Hindu texts, such as Puranic geographies, reference broader interactions across the Gujarat-Sindh corridor but lack specific, verifiable details on Kutch's governance or ethnogenesis, prioritizing mythic over empirical narratives.[2] By the 13th century, the Vaghela dynasty, successors to the Chaulukya Rajputs, exerted nominal supremacy over Kutch as part of their Gujarat domain from circa 1240 to 1304 CE, integrating it into a network of Rajput-controlled territories amid trade routes linking Sindh and the Arabian Sea.[21] The Vaghelas' decline accelerated with the Delhi Sultanate's incursions under Alauddin Khalji around 1299–1304 CE, fragmenting central authority and exposing peripheral regions like Kutch to opportunistic migrations and power vacuums. In the 14th century, Samma Rajputs—originating from Sindh amid the turmoil of Muslim conquests there—incurred southward, establishing initial control over western Kutch by subduing local chieftains and leveraging the region's isolation for consolidation.[2] This marked the ethnogenesis of a semi-autonomous Kutch entity, distinct from Gujarat's core, as Samma branches formed localized principalities amid ongoing invasions, fostering a patchwork of Rajput-led holdings reliant on pastoralism and salt extraction rather than unified statecraft.[21] These chieftaincies, often kin-based and fortified against nomadic threats, set the causal groundwork for subsequent Rajput dominance by institutionalizing clan-based defense and resource control, without reliance on unverified folklore of earlier mythical rulers.[22]Jadeja Dynasty Establishment and Expansion

The establishment of Jadeja rule in Cutch traces to approximately 1147, when Lakho Jadani, originating from the Samma tribe in Sindh, migrated to the region and assumed control following adoption by the local leader Jam Jada, thereby adopting the Jadeja designation for his descendants.[23] Reigning until 1175, Lakho Jadani initiated military campaigns that subdued local chieftains and laid the groundwork for dynastic authority through superior martial organization and strategic alliances with regional powers.[22] Subsequent rulers, including Lakho Phulani, furthered territorial gains by conquering strategic locales such as Kera, where he relocated the capital and fortified defenses against incursions from neighboring Sindhi and Gujarati entities, leveraging cavalry prowess and kinship ties among Rajput clans.[24] By the early 16th century, persistent conflicts with indigenous tribes like the Jats and rival Jadeja branches fragmented control, but these divisions were exploited through targeted expeditions that emphasized mobility and fortified settlements. The dynasty's expansion culminated under Rao Khengarji I, who ruled from 1510 to 1586 and unified Cutch by 1549 via decisive conquests against divided Jadeja factions and adjacent states, consolidating approximately 45,612 square kilometers under centralized rule.[25] He designated Bhuj—initially established by his father Rao Hamirji in 1510—as the capital in 1549, facilitating administrative efficiency amid ongoing threats from Afghan warlords and the emerging Mughal influence in Gujarat.[26] Khengarji I's success stemmed from tactical alliances with local pastoralists and repulse of external raids, preserving autonomy; subsequent diplomatic engagements yielded Mughal firmans affirming semi-independent status, as evidenced by imperial recognitions under Akbar that ratified Jadeja holdings without direct subjugation.[27]Internal Strife and Regency Periods

Following the death of Maharao Deshalji I in 1741, internal power struggles intensified as his son Lakhpatji seized control by imprisoning his father and assuming the throne, ruling until his own death in 1760.[28] Lakhpatji's succession bypassed traditional lines amid familial tensions, setting a precedent for contested authority that fragmented Jadeja clan loyalties. His brother Godji II then acceded (1760–1778), but external invasions from Sindh's Ghulam Shah Kalhora compounded domestic factionalism, culminating in Godji's retirement after humiliating defeats by Sidi forces, leaving a vacuum exploited by rival chiefs.[28] Godji's son Rayadhan III's reign (1778–1786) devolved into chaos marked by the ruler's mental instability and aggressive religious policies, including forced conversions to Islam among state subjects, which alienated Hindu elites and prompted rebellion.[26] In 1786, influential minister Meghji Seth, jagirdar of Anjar, deposed Rayadhan with support from military chief Jamadar Dosalven and Mandvi's ruler, installing Rayadhan's minor brother Prithvirajji (r. 1786–1801) under a regency council.[26] [28] This council, formalized as Bar Bhayat ni Jamat ("Council of Twelve Brothers"), effectively sidelined the titular ruler, with Jamadar Fateh Muhammad emerging as de facto leader from 1786 to 1813, though Prithvirajji died young and Rayadhan was briefly restored in 1801 only to face repeated confinement amid ongoing chief interventions.[26] [28] These regencies and successions fostered feudal fragmentation, where autonomous Jadeja chiefs and ministers prioritized personal ambitions over centralized governance, perpetuating cycles of deposition and civil skirmishes that eroded administrative capacity.[28] Recurrent droughts and famines—seven in the late 18th century (1746, 1757, 1766, 1774, 1782, 1784, 1791), with 1746 particularly devastating—exacted heavy tolls, as power vacuums prevented effective resource allocation or relief, directly contributing to population declines through starvation and migration amid unchecked banditry and unpaid troops. The era's instability amassed state debts from prolonged conflicts and ministerial extravagance, underscoring how dynastic infighting causally amplified environmental vulnerabilities in Kutch's arid terrain.[28]British Protectorate Era

In 1815, amid ongoing internal strife, the Kutch army was defeated near Bhadreswar on 15 December by combined forces of the British East India Company and the Gaekwads of Baroda State, leading to British occupation of areas such as Anjar. This event precipitated further intervention, culminating in the deposition of ruler Bharmalji II and the installation of his minor nephew Deshalji II under a regency council.[26] Following the period of internal disorder under Rao Bharmalji II, characterized by factional conflicts and external threats, the British East India Company formalized the protectorate arrangement in 1819 through the Treaty of 13 October 1819, which established Cutch as a British protectorate, with the Company guaranteeing the "integrity of [the Rao's] dominions, from foreign or domestic enemies" in Article 5, thereby restoring stability after years of anarchy that had undermined governance and revenue collection.[29] In exchange, Cutch agreed to host and fund a British force from its revenues, as stipulated in Article 6, imposing a fixed financial obligation equivalent to a subsidiary subsidy that diverted state funds from internal development but ensured defense against invasions, such as those from Sindh or local bandits.[29] [30] Article 10 of the treaty explicitly preserved Cutch's internal sovereignty by committing the Company to "exercise no authority over the domestic concerns of the Rao," allowing the state to retain control over administration, justice, and customs while a British Resident oversaw external relations from Bhuj per Article 19.[29] This arrangement causally stabilized the region by curbing inter-clan violence through British mediation and arbitration, though the subsidy payments—initially covering troop maintenance—strained fiscal resources, occasionally leading to arrears and renegotiations that highlighted the trade-off between security and economic autonomy.[29] The treaty also mandated suppression of maritime piracy, a longstanding issue in Cutch's coastal waters, with stipulations in the 1816 preliminary agreement and confirmed in 1819 requiring the Rao to end seafaring depredations, which British naval patrols enforced, thereby facilitating safer trade routes in the Arabian Sea and boosting salt exports without direct territorial annexation.[30] [31] Under subsequent rulers, including Pragmalji II (r. 1860–1875) and especially Khengarji III (r. 1875–1942), the protectorate framework enabled modernization initiatives amid colonial oversight, such as the construction of the Prag Mahal palace complex in the 1870s and early port developments at Tuna, which improved connectivity though limited by the subsidy's fiscal drag.[32] Khengarji III, during his 66-year reign, further advanced infrastructure, including the establishment of the Kandla port in 1930 to bypass geographic isolation, while adhering to treaty obligations that maintained internal autonomy until India's independence in 1947, when Cutch acceded without the loss of sovereign functions seen in directly ruled provinces.[32] This suzerainty model thus preserved dynastic continuity and local governance, contrasting with more intrusive alliances elsewhere, by prioritizing protection over interference, though at the cost of revenue dependency that constrained expansive public works until later reforms.[29]Governance and Administration

Rulers and Dynastic Succession

The Jadeja rulers of Cutch State adhered primarily to male primogeniture for succession, though this principle was frequently disrupted by fraternal disputes, assassinations, and periods of instability that necessitated regencies, including those led by queens or noble councils.[33] [34] These interruptions often stemmed from administrative failures, such as factional infighting and fiscal mismanagement, which undermined stability and invited external interventions, including British oversight after 1819.[1] Female regents, such as those during minority rules, played key roles in maintaining continuity, though their influence sometimes exacerbated court extravagance and debt accumulation from opulent lifestyles and patronage.[26] The rulers bore titles evolving from Jam and Rao to Maharao under British recognition, with the state elevated to 17-gun salute status in 1919 during Khengarji III's reign, signifying its prominence among princely states.[26] [35] Jadeja rule, claimed from clan migrations around 1147 but consolidated in the 16th century, persisted until accession to India in 1947, after which titular succession continued.[36] [26]| Ruler | Reign Period | Key Notes on Succession and Reign |

|---|---|---|

| Rao Bhhemji | 1429–1472 | Early consolidator; succession via clan branches amid regional divisions.[37] |

| Rao Hamirji | 1472–1536 | Primogeniture upheld; faced internal Jadeja splits leading to fragmented rule for centuries.[38] |

| Jam Raval | 1540–1548 | Disputed tenure; fled conflicts, enabling rival branches; marked instability before unification.[1] |

| Khengarji I | 1548–1585 | Founder of enduring Jadeja line; stabilized through conquests, though primogeniture later broke.[37] |

| Bharmalji II | 1814–1819 | Regency ended in strife; death led to British treaty imposing protectorate amid debt from court excesses.[26] |

| Deshalji II | 1819–1860 | Assumed after regency; long rule focused on recovery, but administrative lapses persisted.[1] |

| Pragmalji II | 1860–1875 | Primogeniture; minor regency; stability improved under British guidance. |

| Khengarji III | 1875–1942 | Succeeded father directly; longest reign, marked by administrative reforms including famine relief infrastructure, state railway (1900s), and Kandla port selection (1930), enhancing stability despite inherited debts; impartial justice noted in records.[32] [39] |

| Pragmalji III | 1942–1947 | Primogeniture; oversaw accession to India (1947); titular line continued post-integration.[1] |