Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Jind State

View on Wikipedia

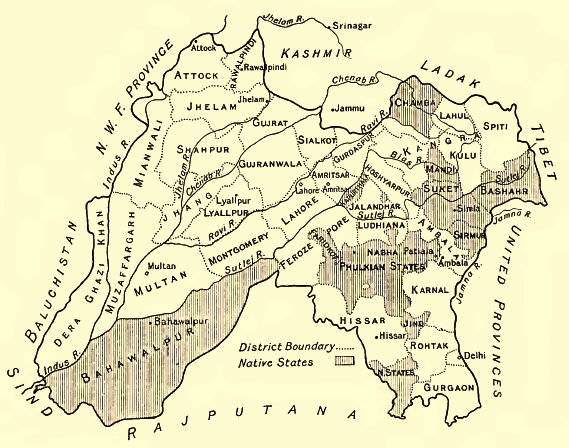

Jind State (also spelled Jhind State) was a princely state located in the Punjab and Haryana regions of north-western India. The state was 3,260 km2 (1,260 sq mi) in area and its annual income was Rs.3,000,000 in the 1940s.[1] This state was founded and ruled by the Jats of Sidhu clan.[2]

Key Information

Location

[edit]The area of the state was 1,259 square miles in total and it ranged from Dadri, Karnal, Safidon, and Sangrur.[1][3]

History

[edit]Origin

[edit]

The ruling house of Jind belonged to the Phulkian dynasty, sharing with the Nabha rulers a common ancestor named Tiloka. Tiloka was the eldest son of Phul Sidhu of the Phulkian Misl.[3] The Jind rulers descended from Sukhchain Singh, the younger son of Tiloka.[4] The Jind State was founded in 1763 by Gajpat Singh after the fall of Sirhind.[3] Other sources give a date of 1768 for the founding of the state.[1]

Gajpat Singh, son of Sukhchain Singh and great-grandson of Phul, launched a rebellion against the hostile authority based out of Sirhind.[1] The rebellion was a Sikh coalition against the Afghan governors of Jind State.[3] As a reward, Gajpat received a large tract of land, which included Jind and Safidon.[3] Gajpat established his headquarters at Jind, building a large, brick fort at the location.[3]

He established the state in 1763 or 1768 and made Sangrur its capital.[1][3] Gajpat was bestowed with the title of Raja by the Mughal emperor Shah Alam in the year 1772.[1][3] As a mark of sovereignty, the Sikh raja minted coins bearing his name.[1][3] Shortly after being bestowed with the raja title by the Mughals, Jind was attacked by Rahim Dad Khan, the governor of Hansi, who was killed in action.[3] In 1774, a dispute arose between Jind and Nabha states.[3] The precarious intra-Phulkian situation led to Gajpat Singh of Jind sending troops against Hamir Singh of Nabha, with the former taking possession of Imloh, Bhadson, and Sangrur from the latter's control.[3] However, the ruler of Patiala State and influential members of the family led to Imloh and Bhadson being returned to Nabha's rule.[3] Sangrur remained with Jind and was not given back to Nabha.[3] A daughter of Gajpat Singh of Jind married Maha Singh of the Sukerchakia Misl and was the mother of Ranjit Singh.[3]

Gajpat Singh ordered the raising of several fortresses, whom were constructed using lakhauri (thin burnt-clay) bricks in the year 1775.[1] One of the forts was built to the left of the present-day Rani Talab and the second was built to the right of present-day Tanga Chowk.[1] There was a family connection shared between Jind State and the Sukerchakia Misl, due to the fact that Gajpat's daughter, Raj Kaur, was the mother of Maharaja Ranjit Singh whom founded the Sikh Empire.[1]

Gajpat Singh died in 1786.[3]

After the passing of Gajpat, his son Bhag Singh succeeded to the throne of Jind in 1789.[1] Bhag Singh is notable as being the first cis-Sutlej or Phulkian Sikh ruler to develop amicable ties with the British East India Company, which developed into a state of allyship between the two parties.[1]

British era

[edit]

It was part of the Cis-Sutlej states until 25 April 1809, when it became a British protectorate.[5] After Bhag Singh died, he would be succeeded by Fateh Singh, who in-turn was followed by Sangat Singh.[1] After the death of Raja Sangat Singh in 1834, some parts of the state were taken over by the British due to the absence of a direct heir. The throne was later gone to his cousin, Swarup Singh.[6] Then the throne passed to Swarup's son, Raghubir Singh.[1] Raghubir Singh did produce an immediate heir in the form of a son named Balbir Singh, but his son had died while young so the line of succession passed to his grandson, Ranbir Singh, who is described as a "philanderer, an extravagant and a philanthropist".[1] Ranbir is noted for being the longest reigning ruler of the Phulkian dynasty.[1] He had twelve children born from his four wives.[1]

When Kaithal was annexed in 1843, the Mahalan Ghabdan pargana was given to Jind State in exchange for a part of Saffdon.[7]

Indian painter Sita Ram produced watercolours of the local scenery (landscape and architecture) of Jind State between June 1814 to early October 1815.[8]

At the Ambala Darbar held in Ambala between 18–20 January 1860, a decision was made to exempt Jind, Patiala, and Nabha states from the doctrine-of-lapse.[9]

During the First World War, the Jind Imperial Service Regiment saw conflict.[1] The state was awarded with a fifteen-gun salute.[1]

On 20 August 1948, with the signing of the instrument of accession, Jind became a part of the Patiala and East Punjab States Union of the newly independent India on 15 July 1948.[1]

Postage stamps prior to King George V consisted of Indian stamps over printed as "Jhind State", with the letter 'H' in the name. On the George V stamps, the 'H' is omitted and is overprinted as "Jind State" (Reference actual stamps from the Victorian, Edward VII and George V eras).

Post-independence

[edit]Ranbir Singh died on 31 March 1948, shortly after he signed the instrument of accession.[1] He was succeeded by his son Rajbir Singh.[1] Rajbir died in 1959 and in-turn was succeeded by his brother named Jagatbir Singh.[1] However, Rajbir's son named Satbir Singh, claims to have been crowned as a successor to his father, leading to a dispute between the brother and son of the late Rajbir.[1]

After the division of Punjab in 1966, the former territories of Jind State were given to the then newly formed state of Haryana.[1] Thus, Jind town and district now form a part of Indian state of Haryana.

The family of the former Jind rulers are mired in family divisions and conflicts over shares of their declining wealth.[1] The Jind royals currently reside at Raja ki Kothi on Amarhedi Road.[1]

Economy

[edit]The revenue per annum of Jind State was around 2,800,000 rupees.[3]

Heritage conservation

[edit]Many monuments and structures related to the erstwhile Jind state lie in disrepair and disregard and few efforts are being taken to conserve them, in-contrast to the heritage of Patiala and Nabha states.[1] Two historical forts (both constructed in 1775 and were located near Rani Talab and Tanga Chowk) related to the history of the state were demolished in the 1990s to make way for newer developments, such as shopping bazaars, a Doordarshan Relay Centre, and parks.[1] There was also a third Jind fort that was demolished in the 1990s as well, it was located beside the fort near Rani Talab.[1] The land the former forts stood on has also suffered from illegal encroachments.[1] Many historical artefacts related to the state have been looted and smuggled.[1] The city of Jind was also known for its three city-gates connected by a border wall, which were named Jhanjh Gate, Ramrai Gate, and Safidon Gate, however these gates have not survived to the present-day.[1] Efforts are ongoing to have the ASI declare the buildings of Rani Talab, Raja-Ki-Kothi, and Khunga Kothi as protected heritage sites.[1] Indo-Saracenic buildings of Jind have fallen into a decrepit condition.[1]

List of rulers

[edit]| Name

(Birth–Death) |

Portrait | Reign | Enthronement | Note(s) | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Start date | End date | |||||

| Sardars | ||||||

| Sukhchain Singh (1683–1758) |

? | 1758 | [4] | |||

| Rajas | ||||||

| Gajpat Singh (15 April 1738 – 11 November 1789) |

|

1758 | 1789 | [10][11][4] | ||

| Bhag Singh (23 September 1760 – 16 June 1819) |

|

1789 | 1819 | November 1789 | [10][11][4] | |

| Fateh Singh (6 May 1789 – 3 February 1822) |

|

1819 | 1822 | [10][11][4] | ||

| Sangat Singh (16 July 1810 – 4/5 November 1834) |

|

1822 | 1834 | 30 July 1822 | [10][11][4] | |

| Swarup Singh (30 May 1812 – 26 January 1864) |

|

1834 | 1864 | April 1837 | [10][11][4] | |

| Raghubir Singh (1832 – 7 March 1887) |

|

1864 | 1887 | 31 March 1864 | [10][11][4] | |

| Ranbir Singh (11 October 1879 – 1 April 1948) |

|

1887 | 1948 | 27 February 1888 | [10][11][4][1] | |

| Titular | ||||||

| Rajbir Singh (1948 – 1959) |

|

1948 | 1959 | [10][12][13] | ||

| Satbir Singh (1940–2023) |

1959 | 2023 | Upon the death of his father, Rajbir Singh, in 1959, Yadavindra Singh, the Maharaja of Patiala, installed him as the Maharaja of Jind. His succession was recognized by the President of India on 12 October 1959.[14] | [10][15][16] | ||

Other titular claimants

[edit]| Other titular claimants | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 9 | Rajbir Singh | 1948–1959 | [11][4][1] |

| 10 | Jagatbir Singh (disputed)[1][a] | 1959 – ? | [17][1][11] |

| 11 | Rambir Singh (1944–1992) |

? – 1992 | [1] |

| 12 | Gajraj Singh (1981–2016) |

1992–2016 | [1] |

| 13 | Jagbir Singh Sidhu (1979–2018) |

2016–2018 | [1] |

| 14 | Gunveer Singh (born 2014) |

2018 – present | [1] |

Administrative divisions and boundaries

[edit]During the British era (1901), Jind State was divided into two nizāmats (districts): Sangrur and Jind. Each nizāmat was further subdivided into tahsils,[6] which were not contiguous with each other, The State contained 7 towns and 439 villages, with a total physical area of 1,268 square miles:

| 1901 State Administration | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | District/Nizāmat | Tahsil | Remark | Today | |

| I | Sangrur Nizāmat | Sangrur | Capital; included all scattered territories | Punjab | Bathinda, Patiala, Sangrur District |

| II | Jind Nizāmat | Jind | Former capital | Haryana | Jind District |

| III | Dadri | Gained in 1858; southern enclave | Haryana | Charkhi Dadri District | |

I. Sangrur Tahsil

[edit]Sangrur Tahsil was one of the three tahsils of Jind State and was part of the Sangrur Nizāmat. It was not in one piece but made up of four separate areas, surrounded by British territory and lands of Patiala and Nabha States.

- The Sangrur Ilāqa was the main region of the state and included the capital town of Sangrur. It was bordered to the North: Patiala and Nabha territories, East: Bhawanigarh Nizāmat of Patiala ,South: Sunam Tahsil of Patiala and the village of Khadial (Kaithal Tahsil, Karnal District – former Kaithal state enclave), West: Barnala Tahsil of Patiala & Dhanaula Thana of Nabha. The ilāqa comprised 1 Sangrur town and 43 villages including Ghabdan, badrukha village, covering 109 square miles, with a population of 36,598 according to the 1901 Census. Today, this area forms part of Sunam and Sangrur tahsils in Sangrur district.

- The Kularan Ilāqa was located about 20 miles east of Sangrur and was almost completely surrounded by Patiala territory, with one side bordering Kaithal Tahsil. It included 33 villages, had a population of 14,976, and covered an area of 66 square miles. It is located near the town of Samana and today is part of Samana Tahsil in Patiala district.

- The Wazidpur Ilāqa was a small, fragmented area made up of two parts of Jind State. The northern part had four villages, and the southern part had three villages, Total 7 villages. The area covered just 9 square miles and had a population of 2,361 in 1901. Today, these areas are near Patiala town, between Patiala and Samana, and part of Patiala district.

- The Balanwali Ilāqa was a large, detached area located 48 miles west of Sangrur, made up of three separate parts of state territory, Together, the Balanwali Ilāqa covered 57 square miles and had a population of 10,746 in 1901.

- The main area included the town of Balanwali and 10 villages. It was bordered on the northeast by Nabha State, on the east and south by Patiala, and on the west by the Mehraj pargana of Moga Tahsil in Ferozepore District. Today, this area is part of Rampura Phul Tahsil in Bathinda district.

- Another part lay to the north, containing the large village of Dialpura, held as Jagir by the Sardars of Dailpura. It was bordered by Nabha on the southeast, the Mehraj pargana of Ferozepore on the southwest, and Patiala on the northwest. Today, it falls within Rampura Tahsil of Bathinda district and is known as Dyalpura Mirza village and its surrounding area.

- The third part, south of Balanwali, included two isolated villages, Mansa and Burj, both surrounded entirely by Patiala territory. Today, these villages are part of Maur Tahsil, Bathinda district, known as Mansa Kalana and Burj village.

The tahsil of Sangrur lies almost entirely in the great tract known as the Jangal, with only seven villages around wazidpur situated in the Pawadh region. At that time, Sangrur Tahsil included 95 villages and 2 towns (Sangrur, Balanwali), covering a total area of 241 square miles (19% of the state) with a population of 64,681 (22.93% of the state) in 1901.

Today, the former Sangrur Tahsil of Jind State lies entirely in Punjab, India with parts falling within Sangrur, Patiala & Bathinda District.

II. Jind Tahsil

[edit]Jind Tahsil was a compact and connected triangular part of state, unlike Sangrur Tahsil, which was divided into parts. It was mostly surrounded by British and Patiala state territories and bordered by: North: Narwana Tahsil (Patiala state) and Kaithal Tahsil (Karnal), East: Panipat Tahsil (Karnal), South-East: Gohana Sub-Tahsil(Rohtak), South: Rohtak Tahsil (Rohtak), West: Hansi Tahsil (Hissar District).

Villages in Jind Tahsil were historically grouped into tappās, The tappās in Jind Tahsil were:

| Tappā Name | No. of Villages | Tappā Name | No. of V. | Tappā Name | No. of V. | Tappā Name | No. of V. |

| Chahutra | 2 | Bārah | 15 | Lājwāna Kalān | 13 | Kalwa | 13 |

| Dhāk | 1 | Kānāna | 21 | Kānāna | 21 | Saffidon | 26 |

| Kandeḷa | 31 | Rām Rāi | 18 | Hat | 12 | Total | 165 |

Jind Tahsil lies entirely in the Bangar region. It included the two towns of Jind and Safidon, along with 163 villages. The tahsil covered 464 square miles area (36.62% of the state) and had a population of 124,954 (44.3% of the state) in 1901.

Today, the entire tahsil lies in Haryana, within Jind district.

III. Dadri Tahsil

[edit]Dādri Tahsil was also a compact and contiguous part of State, unlike Sangrur Tahsil, in parts. It lay to the south of Jind Tahsil and was separated from it by Rohtak Tahsil of British territory, making it another enclave of the state. This tahsil was bordered by: East: Jhajjar Tahsil (Rohtak), North-West: Bhawani Tahsil (Hissar District) South: Duana State, Bawal Nizāmat (Nabha State) & Mahendragarth Nizāmat (Patiala State), West: Loharu State.

Villages in Dadri Tahsil were also grouped into tappās, The tappās in Jind Tahsil were:

| Tappā Name | No. of Villages | Tappā Name | Number of Vill. | Tappā Name | Number of V. |

| Phoghāt | 20 | Sangwān | 55 | Pachisi | 8 |

| Punwār | 31 | Sheorān | 43 | Satganwa | 9 |

| Chogānwā | 6 | Haweli | 11 | Total | 183 |

Dadri Tahsil lies in the Bagar region, Historically and in the present day, it is also known as Dalmia Dadri or Charkhi Dadri. It included 3 towns (Dadri, Kalyana, Baund) and 181 villages, covering a total area of 562 square miles (44.35% of the state) and had a population of 120,451 (32.75%) according to the 1901 census.

Today, the entire tahsil lies in Haryana, mostly within Charkhi Dadri district.

Demographics

[edit]| Religious group |

1881[18][19][20] | 1891[21] | 1901[22] | 1911[23][24] | 1921[25] | 1931[26] | 1941[27] | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | |

| Hinduism |

210,627 | 84.3% | 230,846 | 81.12% | 211,963 | 75.16% | 210,222 | 77.36% | 234,721 | 76.16% | 243,561 | 75.02% | 268,355 | 74.17% |

| Islam |

34,247 | 13.71% | 38,508 | 13.53% | 38,717 | 13.73% | 37,520 | 13.81% | 43,251 | 14.03% | 46,002 | 14.17% | 50,972 | 14.09% |

| Sikhism |

4,335 | 1.73% | 15,020 | 5.28% | 29,975 | 10.63% | 22,566 | 8.3% | 28,026 | 9.09% | 33,290 | 10.25% | 40,981 | 11.33% |

| Jainism |

649 | 0.26% | 173 | 0.06% | 1,258 | 0.45% | 1,233 | 0.45% | 1,548 | 0.5% | 1,613 | 0.5% | 1,294 | 0.36% |

| Christianity |

3 | 0% | 7 | 0% | 80 | 0.03% | 187 | 0.07% | 637 | 0.21% | 210 | 0.06% | 161 | 0.04% |

| Zoroastrianism |

0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 3 | 0% |

| Buddhism |

0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 3 | 0% |

| Judaism |

N/a | N/a | 6 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% |

| Others | 1 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 10 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 43 | 0.01% |

| Total population | 249,862 | 100% | 284,560 | 100% | 282,003 | 100% | 271,728 | 100% | 308,183 | 100% | 324,676 | 100% | 361,812 | 100% |

| Note: British Punjab province era district borders are not an exact match in the present-day due to various bifurcations to district borders — which since created new districts — throughout the historic Punjab Province region during the post-independence era that have taken into account population increases. | ||||||||||||||

Gallery

[edit]-

Raja Gajpat Singh of Jind State

-

Raja Sangat Singh of Jind State

-

Raja Swarup Singh of Jind State

-

Miniature painting of Sardar Daya Singh Sibia of Ramgarh, revenue minister of Jind State during the reign of Maharaja Raghubir Singh

-

Photograph taken in the erstwhile Jind State

-

Stamp of the Jind State. Edward VII, 1905

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Rajbir's other son Satbir Singh also claims to have been coronated.

- ^ 1931-1941: Including Ad-Dharmis

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq Malik, Satyawan (25 January 2020). "Jind monuments a picture of neglect". The Tribune. Archived from the original on 24 September 2023. Retrieved 9 September 2023.

- ^ Bates, Crispin (26 March 2013). Mutiny at the Margins: New Perspectives on the Indian Uprising of 1857: Volume I: Anticipations and Experiences in the Locality. SAGE Publishing India. ISBN 978-81-321-1589-2. Archived from the original on 10 February 2024. Retrieved 29 January 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Dhingra, Behari Lal (1930). Jind State: A Brief Historical and Administrative Sketch (With Some Photographs). Bombay: Time of India Press.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Singh, Bhagat (1993). "Chapter 14 - The Phulkian Misl". A History of the Sikh Misals. Publication Bureau, Punjabi University.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 15 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 416.

- ^ a b Source: Phulkian States, Patiala Jind And Nabha Gazetteers Vol Xvii A, 1904

- ^ Source: Page no. 216, Phulkian States, Patiala Jind And Nabha Gazetteers Vol Xvii A, 1904

- ^ Tilak, Sudha G. (16 November 2023). "Sita Ram: The unknown Indian artist who painted for British rulers". BBC. Retrieved 23 August 2024.

- ^ Chatterji, Prashanto K. (1975). The Making of India Policy, 1853-65: A Study on the Relations of the Court of Directors, the India Board, the India Office, and the Government of India. University of Burdwan. pp. 152–153. ISBN 9780883868188.

Eventually, at the Ambala Durbar (18-20 January 1860), Canning himself promised the three chiefs Sanads, guaranteeing their possessions to themselves and their heirs and the right to adopt from the Phoolkan family whenever ...

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "JIND". 4 August 2017. Archived from the original on 4 August 2017. Retrieved 25 May 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Kumar, Vijender (29 December 2018). "Jind royal family scion passes away". The Times of India. ISSN 0971-8257. Archived from the original on 7 February 2023. Retrieved 7 February 2023.

The first king of the estate was Raja Gajpat Singh who died in 1789. After that Raja Bhag Singh took charge as king in 1789 and died in 1819. Next, Raja Fateh Singh ruled from till February 3, 1822, followed by Raja Sangat Singh from July 30, 1822, to November 1834. He was followed by Raja Sarup Singh till January 1864, Raja Raghubir Singh till 1887, Maharaja Ranbir Singh till 1948 and Rajbir Singh in 1948," Bhardwaj added.

- ^ "Counsel clears air on erstwhile royal family". The Tribune. Retrieved 25 May 2025.

- ^ Gandhi, Surjit Singh (1980). Struggle of the Sikhs for Sovereignty. Gur Das Kapur. p. 350.

- ^ Directorate of Printing, Government of India (17 October 1959). Gazette of India, 1959, No. 486. p. 2904.

- ^ "Guest column: Life and legacy of the last Maharaja of Punjab". Hindustan Times. 17 September 2023. Archived from the original on 29 September 2023. Retrieved 25 May 2025.

- ^ "Dalit activists protest on Punjab's Sangrur jail premises, demand 927 acres of erstwhile Jind Riyasat to set up 'Begampura'". The Indian Express. 23 May 2025. Retrieved 25 May 2025.

- ^ Kumar, Vijender (29 December 2018). "Jind royal family scion passes away". The Times of India. ISSN 0971-8257. Archived from the original on 7 February 2023. Retrieved 8 February 2023.

The historian said that after Rajbir Singh's death his brother Jagatbir Singh was crowned but he never ruled as after Independence all 562 princely estates merged with India. Jagatbir had one son Kunwar Rambir Singh who married present day Inder Jeet Kaur. He died in 1972 at the age of 42. Kunwar Rambir's both sons are dead now and Rani Inder Jeet Kaur holds the title.

- ^ "Census of India, 1881 Report on the Census of the Panjáb Taken on the 17th of February 1881, vol. I." 1881. JSTOR saoa.crl.25057656. Retrieved 26 December 2024.

- ^ "Census of India, 1881 Report on the Census of the Panjáb Taken on the 17th of February 1881, vol. II". 1881. p. 14. JSTOR saoa.crl.25057657. Retrieved 26 December 2024.

- ^ "Census of India, 1881 Report on the Census of the Panjáb Taken on the 17th of February 1881, vol. III". 1881. p. 14. JSTOR saoa.crl.25057658. Retrieved 26 December 2024.

- ^ Edward Maclagan, Sir (1891). "The Punjab and its feudatories, part II--Imperial Tables and Supplementary Returns for the British Territory". p. 14. JSTOR saoa.crl.25318669. Retrieved 26 December 2024.

- ^ "Census of India 1901. [Vol. 17A]. Imperial tables, I-VIII, X-XV, XVII and XVIII for the Punjab, with the native states under the political control of the Punjab Government, and for the North-west Frontier Province". 1901. p. 34. JSTOR saoa.crl.25363739. Retrieved 30 March 2024.

- ^ "Census of India 1911. Vol. 14, Punjab. Pt. 2, Tables". 1911. p. 27. JSTOR saoa.crl.25393788. Retrieved 30 March 2024.

- ^ Kaul, Harikishan (1911). "Census Of India 1911 Punjab Vol XIV Part II". p. 27. Retrieved 30 March 2024.

- ^ "Census of India 1921. Vol. 15, Punjab and Delhi. Pt. 2, Tables". 1921. p. 29. JSTOR saoa.crl.25430165. Retrieved 30 March 2024.

- ^ "Census of India 1931. Vol. 17, Punjab. Pt. 2, Tables". 1931. p. 277. JSTOR saoa.crl.25793242. Retrieved 30 March 2024.

- ^ India Census Commissioner (1941). "Census of India, 1941. Vol. 6, Punjab". p. 42. JSTOR saoa.crl.28215541. Retrieved 30 March 2024.

External links

[edit] Media related to Jind State at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Jind State at Wikimedia Commons

Jind State

View on GrokipediaGeography

Location and Terrain

Jind State was located in the Punjab region of north-western India, spanning territories that correspond to parts of present-day Haryana and Punjab states. The state's capital, Jind, lay approximately 110 kilometers northwest of Delhi in central Haryana.[3] Its lands were bounded to the west by Loharu, southeast by Dujana, and south by the Narnaul district, while being detached from contiguous British-administered areas like Rohtak.[4] The terrain of Jind State comprised flat alluvial plains characteristic of the Indo-Gangetic depositional zone, with average elevations ranging from 220 to 250 meters above sea level.[5] These low-lying expanses supported extensive agriculture, irrigated primarily by canal systems and groundwater, though the region experienced semi-arid conditions with hot summers reaching over 45°C and cold winters dipping below 5°C.[6] Soils in the area were predominantly sandy loam to loam, calcareous in nature, and often featured a kankar (calcareous nodule) layer at depths of 0.75 to 1.25 meters. These soils were generally deficient in nitrogen, phosphorus, and potash, necessitating fertilization for crop productivity, with major cultivable lands devoted to wheat, cotton, and gram.[7] Alkaline and saline patches, particularly in irrigated zones, posed challenges, alongside occasional wind erosion in drier tracts.[7]Boundaries and Territorial Extent

Jind State encompassed a non-contiguous territory in southeastern Punjab, divided into three principal tahsils: Jind, Sangrur, and Dadri, totaling 1,268 square miles.[8] The configuration featured scattered tracts amid British districts and adjacent Phulkian states, reflecting historical fragmentation from expansions and alliances.[8] The Jind tahsil formed a compact triangular area of 464 square miles, measuring 36 miles east-west and 24.5 miles north-south, bordered north by Narwana tahsil in Patiala State and Kaithal tahsil in British Karnal district, east by Pampat tahsil in Karnal, south by Rohtak district, and west by Hansi tahsil in Hissar district.[8] Sangrur tahsil, covering 109 square miles, comprised four dispersed areas—Sangrur, Kuldran, Bazidpur, and Balanwali—bounded north and east by Patiala State territories including Bhawanigarh nizamat and Sunam tahsil, south by Kharak village in Karnal, and west by Barnala tahsil in Patiala and Dhanaula thana in Nabha State.[8] Dadri tahsil extended over 562 square miles in a 30-by-23-mile rectangle oriented northeast-southwest, including hilly outcrops such as Kaliana hill (282 acres), with boundaries east adjoining Dujana State and Bawani nizamat in Nabha, south by Loharu State, and west by Bhawani tahsil in British Hissar district; its southeastern Mohindargarh nizamat bordered Jaipur State territory to the south and west.[8] Overall, the state's external limits adjoined British districts of Ludhiana to the north, Ambala and Karnal to the east, Hissar and Rohtak to the south, and Ferozepore and Faridkot to the west, alongside fellow Phulkian states Patiala and Nabha, with southern extensions touching Jaipur territories.[8] This dispersed layout, spanning roughly 29° to 31° N latitude and 74° to 77° E longitude, underscored Jind's position within the cis-Sutlej Phulkian confederation under British protection.[8]History

Origins of the Phulkian Dynasty

The Phulkian dynasty originated with Chaudhary Phul Sidhu-Brar, a chieftain of the Sidhu-Brar Jat clan born in 1627 CE as the second son of Rup Chand and Mata Ambi in the village of Phul, located in present-day Bathinda district, Punjab.[9] Rup Chand, a local zamindar, died fighting Mughal forces when Phul was young, leaving him to navigate a turbulent era of imperial decline and regional power struggles.[9] Phul aligned himself with the Sikh Gurus, beginning service under Guru Hargobind—the sixth Guru, known for militarizing the Sikh community—and continuing under Gurus Har Rai and Har Krishan, whose blessings are traditionally credited with fortifying his lineage's resilience and expansion.[9] This allegiance provided Phul not only spiritual legitimacy but also practical alliances amid the weakening Mughal grip on Punjab's Malwa tract. By the mid-17th century, Phul had established a foothold in Rampura Phul, constructing the Phul Fort (also known as Mubarak or Phulkian Fort) as a defensive stronghold that symbolized the clan's emerging autonomy.[10] Through military exploits, land grants, and strategic marriages, he consolidated jagirs in the fertile Doab and cis-Sutlej regions, laying the groundwork for familial branches that would evolve into sovereign entities.[9] Phul's death in 1689 marked the transition to his progeny, who capitalized on the power vacuum following Aurangzeb's death in 1707 and Afghan incursions, transforming petty chieftaincies into misls and later princely states.[9] Phul fathered multiple sons, with key lines descending from figures such as Tiloka and Rama, whose descendants proliferated amid the Sikh Confederacy's rise in the early 18th century.[11] The dynasty's structure reflected Jat agrarian roots, emphasizing martial prowess and land control rather than feudal nobility, though later rulers invoked descent from Rawal Jaisal, the 12th-century Bhati Rajput founder of Jaisalmer, to bolster prestige—a claim common among upwardly mobile clans but unsubstantiated by contemporary Mughal or Sikh records identifying them as Jats.[9] This foundational era positioned the Phulkians as key players in Punjab's transition from Mughal satrapies to semi-independent polities, with branches specializing in cis-Sutlej defense against Afghan warlords like Ahmad Shah Abdali. The clan's cohesion derived from shared origins in Phul's cult of Guru devotion and territorial pragmatism, enabling survival where rival misls fragmented.[9]Foundation and Early Expansion

Jind State originated from the Phulkian Misl, one of the twelve Sikh confederacies active in the 18th century, established by Chaudhary Phul (1627–1689), a Sidhu Jat chieftain whose descendants formed the ruling dynasty.[1][9] Phul's lineage provided the foundational jagirs in the Punjab region, with his great-grandson, Raja Gajpat Singh (1738–1789), formalizing the state in 1763 by consolidating control over the town of Jind, which became the capital.[2][12] Born on April 15, 1738, as the second son of Sukhchain Singh, Gajpat Singh inherited a jagir and expanded it through military engagements aligned with Sikh forces against regional threats, including Afghan incursions.[13][14] Under Gajpat Singh's rule, Jind State underwent significant early expansion, as he annexed additional territories to his original holdings, enhancing the state's territorial extent in the Cis-Sutlej region.[2][1] By 1775, he constructed a fort at Jind to fortify the capital against invasions, reflecting the state's growing strategic importance amid the power vacuum following Mughal decline and Sikh resurgence.[15] This period saw Jind asserting independence while navigating alliances, often under nominal Maratha influence, though primary sovereignty derived from Phulkian martial traditions rather than external overlords.[2] Following Gajpat Singh's death in 1789, his son Bhag Singh (r. 1789–1818) continued consolidation, maintaining the state's autonomy through diplomatic maneuvering and military defense, setting the stage for formal recognition as a princely entity.[2][13] The early rulers' focus on territorial acquisition and fortification laid the groundwork for Jind's endurance as a Phulkian power amid the turbulent 18th-century Punjab landscape.[12]Relations with Sikh Empire and Afghans

In the mid-18th century, the Phulkian territories that would form Jind State faced repeated incursions from Afghan forces under Ahmad Shah Durrani and his governors. The Phulkian misl, including figures like Ala Singh of Patiala, engaged in defensive actions against Durrani's invasions, such as the 1748 battle at Manpur where Ala Singh allied with Mughal forces to repel Afghan advances.[16] By 1762, Afghan pressure intensified, leading Ala Singh to submit temporarily and agree to annual tribute payments to Ahmad Shah, reflecting the precarious balance of tribute and resistance maintained by Phulkian leaders to preserve autonomy amid broader Sikh-Afghan conflicts.[17] The foundation of Jind State in 1763 directly stemmed from resistance to Afghan authority. Raja Gajpat Singh, a great-grandson of the Phulkian progenitor Chaudhary Phul, participated in a Sikh coalition that attacked Sirhind, defeating and killing Zain Khan, the Afghan governor of the province, in a pivotal engagement that weakened Durrani influence in the region.[12] [1] As a reward for this victory, Gajpat Singh received a substantial tract of land encompassing Jind and surrounding areas, establishing the state's core territory independent of Afghan overlordship and marking a shift toward consolidated Phulkian control in the Malwa region south of the Sutlej River.[12] Relations with the Sikh Empire under Maharaja Ranjit Singh were characterized by tension and resistance to absorption. The Phulkian states, including Jind, maintained independence from the Lahore Durbar, refusing alignment with Ranjit Singh's unification efforts due to their established autonomy and smaller-scale governance structures.[18] Ranjit Singh exerted military pressure on the Cis-Sutlej Phulkian territories, seeking to expand eastward, but these ambitions were curtailed by the 1809 Treaty of Amritsar between the British East India Company and Ranjit Singh, which recognized the Sutlej River as a boundary and effectively shielded Jind, Patiala, and Nabha from Sikh conquest by affirming British influence in the region.[19] Subsequent Jind rulers, such as Bagh Singh (r. 1790–1818), navigated ongoing Sikh overtures by forging protective alliances with the British, who viewed the Phulkians as buffers against Ranjit Singh's expansionism. This strategic alignment allowed Jind to avoid direct subjugation, preserving its sovereignty until British paramountcy formalized protectorates in the early 19th century, while Ranjit Singh focused conquests northward and westward without successfully incorporating the Malwa Phulkian states.[12]Establishment as British Protectorate

In the early 19th century, the Phulkian state of Jind, located south of the Sutlej River, confronted expansionist pressures from Maharaja Ranjit Singh's Sikh Empire, which sought to consolidate control over the Punjab region. The rulers of the Cis-Sutlej states, including Jind, Patiala, and Nabha, increasingly turned to the British East India Company for alliance against this northern threat, recognizing the Company's growing military presence in northern India following victories in the Maratha Wars.[20] On 25 April 1809, Jind formally entered into a protective relationship with the British through engagements tied to the Treaty of Amritsar, signed that same day between the East India Company and Ranjit Singh. This treaty demarcated the Sutlej River as the boundary between Sikh territories north of the river and the Cis-Sutlej principalities to the south, with the British guaranteeing the independence and security of the latter against Sikh incursions. Under Raja Bhag Singh (r. 1789–1819), Jind accepted British overlordship in external affairs, ceding rights to conduct independent foreign policy while retaining autonomy in internal governance, taxation, and administration.[21][20][22] This protectorate status marked a pivotal shift for Jind, embedding it within the British imperial framework in Punjab and fostering a period of relative stability that allowed territorial consolidation and economic recovery. The arrangement proved mutually beneficial initially, as British protection deterred Afghan and Sikh aggression, enabling Jind to focus on internal development without the constant warfare that plagued independent polities in the region.[2]Loyalty During the 1857 Revolt

Raja Sarup Singh, ruler of Jind State from 1837 to 1864, demonstrated loyalty to the British East India Company during the Indian Rebellion of 1857. Upon receiving news of the mutiny at Delhi on May 12, 1857, while at the state capital of Sangrur, he promptly offered his troops and personal services to the British authorities.[23][24] Sarup Singh led his forces on forced marches to Karnal, where he occupied the cantonment with approximately 800 men and secured the ferry over the Yamuna River, preventing rebel advances.[12] He joined the British camp at Alipur on June 7, 1857, remaining until June 25 to support operations before returning to address local threats, including suppressing rebels from Hansi and Hisar districts.[23][1] As part of the Phulkian confederacy, Jind's support aligned with that of Patiala and Nabha, providing crucial military aid in Punjab that helped stabilize British control in the region amid widespread sepoy unrest.[25] This allegiance, rooted in prior treaties and strategic interests, was rewarded post-revolt with territorial expansions and honors, including sanads confirming hereditary rule.[26][27]Administrative Reforms in the Late 19th-20th Centuries

Following the loyalty demonstrated during the 1857 revolt, Jind State, as a British protectorate, pursued administrative modernization influenced by imperial models. Raja Sarup Singh (r. 1837–1864) initiated key reforms in revenue collection and police organization, aligning them with British practices to enhance efficiency and central control.[12] He also enacted social measures, prohibiting sati, slavery, and female infanticide, with strict enforcement to curb these customs.[2] Revenue assessment advanced with the first summary cash-based settlement in Narwana tahsil during 1861–1862, conducted by M. Kale Khan, which estimated produce values over a period to standardize taxation.[28] Under Raja Raghbir Singh (r. 1864–1887), administrative stability was reinforced by swiftly quelling the Dadri insurrection in 1864 using 2,000 state troops, restoring order within six weeks.[12] Maharaja Ranbir Singh (r. 1887–1948), formally installed in 1899 after a regency council oversaw his minority, expanded progressive governance. He introduced free primary education across the state, constructing schools and colleges to promote literacy.[29] Infrastructure improvements included building hospitals and medical dispensaries, alongside establishing charities for widows and orphans of state servants.[2] [12] These initiatives reflected British-inspired welfare and administrative rationalization, with the state providing military contingents for imperial campaigns such as the Tirah Expedition in 1897.[29] By the early 20th century, Jind's administration integrated modern elements while retaining princely autonomy, contributing to regional stability under British paramountcy until accession to India in 1947.[2]Merger into Independent India

Maharaja Ranbir Singh, who had ruled Jind State since 1887, signed the Instrument of Accession to the Dominion of India on 15 August 1947, the day of India's independence, thereby ceding control over defense, external affairs, and communications to the central government while retaining internal autonomy.[30] [29] This act aligned Jind with the Indian Union amid the partition of British India, reflecting the state's prior loyalty to British authorities and its strategic position in Punjab.[2] Ranbir Singh died on 31 March 1948, after a reign of 61 years, leaving succession to his son, Rajbir Singh.[29] Under Rajbir Singh, Jind participated in negotiations for greater integration, joining a covenant signed on 5 May 1948 by rulers of eight East Punjab states—including Patiala, Jind, Nabha, and Kapurthala—to form the Patiala and East Punjab States Union (PEPSU).[31] PEPSU was officially established on 15 July 1948 as a single administrative entity within India, with Patiala's Maharaja Yadavindra Singh as Rajpramukh, effectively dissolving Jind's separate princely status while preserving some privy purse privileges until their abolition in 1971.[30] This merger into PEPSU marked the full incorporation of Jind's territories—totaling approximately 1,259 square miles and encompassing tahsils like Sangrur, Jind, and Dadri—into India's federal structure, facilitating post-independence consolidation in the region amid refugee resettlement from partition violence.[2] PEPSU itself persisted as a distinct state until 1 November 1956, when it was reorganized and absorbed into the enlarged Punjab state following the States Reorganisation Act.[31]Governance and Administration

List of Rulers

The rulers of Jind State belonged to the Phulkian dynasty, tracing descent from Chaudhary Phul, and held the title of Raja until elevated to Maharaja for later incumbents.[2][32] The state was founded in 1763 by Gajpat Singh, who consolidated territory amid Sikh and Afghan conflicts.[12]| Ruler | Reign | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Gajpat Singh | 1763–1789 | Founder; born circa 1738, died 1789; expanded holdings including Jind town.[32][12] |

| Bhag Singh | 1789–1819 | Born 1768, died 1819; supported British against Marathas; regency by widow after early death of sons.[2][32] |

| Fateh Singh | 1819–1822 | Born 1789, died 1822; brief rule ended prematurely; succeeded by minor son amid succession issues.[32][12] |

| Sangat Singh | 1822–1834 | Born 1811, died 1834; ruled under regency; died without issue, leading to interregnum.[2][32] |

| Sarup Singh | 1837–1864 | Born circa 1812, died 1864; selected successor; allied with British, introduced reforms.[2][32] |

| Raghbir Singh | 1864–1887 | Born 1832, died 1887; loyal during 1857 revolt; held titles including GCSI.[2][12] |

| Ranbir Singh | 1887–1947 | Born 1879, died 1948; ascended at age 8 under regency; title Maharaja from 1911; ruled until accession to India.[32][12] |

| Rajbir Singh | 1948 | Born 1918, died 1959; titular Maharaja; oversaw merger into Patiala and East Punjab States Union.[2][12] |