Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Princely state

View on Wikipedia| Colonial India | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

| Princely state |

|---|

| Individual residencies |

| Agencies |

|

| Lists |

A princely state (also called native state) was a nominally sovereign[1] entity of the British Raj that was not directly governed by the British, but rather by an indigenous ruler under a form of indirect rule,[2] subject to a subsidiary alliance and the suzerainty or paramountcy of the British Crown.

In 1920, the Indian National Congress party under the leadership of Mahatma Gandhi declared swaraj (self-rule) for Indians as its goal and asked the princes of India to establish responsible government.[3] Jawaharlal Nehru played a major role in pushing Congress to confront the princely states and declared in 1929 that "only people who have the right to determine the future of the Princely States must be the people of these States".[4] In 1937, the Congress won in most parts of India (excluding the princely states) in the 1937 state elections, and started to intervene in the affairs of the states.[4] In the same year, Gandhi played a major role in proposing a federation involving a union between British India and the princely states, with an Indian central government. In 1946, Nehru observed that no princely state could prevail militarily against the army of independent India.[5]

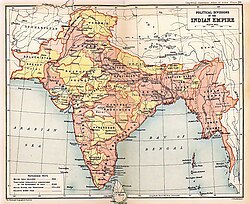

At the time of the British withdrawal, 565 princely states were officially recognized in the Indian Subcontinent,[6] apart from thousands of zamindari estates and jagirs. In 1947, princely states covered 40% of the area of pre-independence India and constituted 23% of its population.[citation needed] The most important princely states had their own Indian political residencies: Hyderabad of the Nizams, Mysore, Pudukkottai and Travancore in the South, Jammu and Kashmir and Gwalior in North and Indore in Central India. The most prominent among those – roughly a quarter of the total – had the status of a salute state, one whose ruler was entitled to a set number of gun salutes on ceremonial occasions.[citation needed]

The princely states varied greatly in status, size, and wealth; the premier 21-gun salute states of Hyderabad and Jammu and Kashmir were each over 200,000 km2 (77,000 sq mi) in size. In 1941, Hyderabad had a population of over 16 million, while Jammu and Kashmir had a population of slightly over 4 million. At the other end of the scale, the non-salute principality of Lawa covered an area of 49 km2 (19 sq mi), with a population of just below 3,000. Some two hundred of the lesser states even had an area of less than 25 km2 (10 sq mi).[7][8]

History

[edit]

The princely states at the time of Indian independence were mostly formed after the disintegration of the Mughal Empire. Many princely states had a foreign origin due to the long period of external migration to India. Some of these were the rulers of Hyderabad (Turco-Persians), Bhopal (Afghans) and Janjira. Among the Hindu kingdoms, most of the rulers were Kshatriya. Only the Rajput states, Manipur, and a scattering of South Indian kingdoms could trace their lineage to the pre-Mughal period.[9]

The standard list of Princely States, the Alqabnamah, began alphabetically with Abu Dhabi.[10] The list also features Bhutan, Bahrain, and Ajman as "Protectorates" of the Viceroy, and features Nepal as an "independent state", with the Aga Khan also appearing as a prince without any land.[11]

British relationship with the princely states

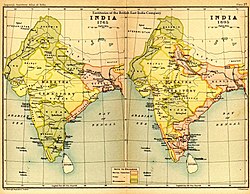

[edit]India under the British Raj (the "Indian Empire") consisted of two types of territory: British India and the native states or princely states. In its Interpretation Act 1889, the British Parliament adopted the following definitions:

(4.) The expression "British India" shall mean all territories and places within Her Majesty's dominions which are for the time being governed by Her Majesty through the Governor-General of India or through any governor or other officer subordinate to the Governor-General of India.

(5.) The expression "India" shall mean British India together with any territories of any native prince or chief under the suzerainty of Her Majesty exercised through the Governor-General of India, or through any governor or other officer subordinate to the Governor-General of India.[12]

In general the term "British India" had been used (and is still used) also to refer to the regions under the rule of the East India Company in India from 1774 to 1858.[13][14]

The British Crown's suzerainty over 175 princely states, generally the largest and most important, was exercised in the name of the British Crown by the central government of British India under the Viceroy; the remaining approximately 400 states were influenced by Agents answerable to the provincial governments of British India under a governor, lieutenant-governor, or chief commissioner.[15] A clear distinction between "dominion" and "suzerainty" was supplied by the jurisdiction of the courts of law: the law of British India rested upon the legislation enacted by the British Parliament, and the legislative powers those laws vested in the various governments of British India, both central and local; in contrast, the courts of the princely states existed under the authority of the respective rulers of those states.[15]

Princely status and titles

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2024) |

The Indian rulers bore various titles including Maharaja or Raja ("king"), Emir, Raje, Nizam, Wadiyar (used only by the Maharajas of Mysore, meaning "lord"), Agniraj Maharaj for the rulers of Bhaddaiyan Raj, Chogyal, Nawab ("governor"), Nayak, Wāli, Inamdar,[16] Saranjamdar[17] and many others. Whatever the literal meaning and traditional prestige of the ruler's actual title, the British government translated them all as "prince", to avoid the implication that the native rulers could be "kings" with status equal to that of the British monarch.

More prestigious Hindu rulers (mostly existing before the Mughal Empire, or having split from such old states) often used the title "Raja", or a variant such as Raje, Rai, Rana, Babu, Rao, Rawat, or Rawal. Also in this 'class' were several Thakurs or Thai ores and a few particular titles, such as Sardar, Mankari, Deshmukh, Sar Desai, Istamuradar, Saranjamdar, Raja Inamdar, etc. The most prestigious Hindu rulers usually had the prefix "maha-" ("great", compare for example "grand duke") in their titles, as in Maharaja, Maharana, Maharao, etc. This was used in many princely states including Nagpur, Kolhapur, Gwalior, Baroda, Mewar, Travancore and Cochin. The state of Travancore also had queens regent styled Maharani, applied only to the sister of the ruler in Kerala.

Muslim rulers almost all used the title "Nawab" (the Arabic honorific of naib, "deputy") originally used by Mughal governors, who became de facto autonomous with the decline of the Mughal Empire, with the prominent exceptions of the Nizam of Hyderabad & Berar, the Wali/Khan of Kalat and the Wali of Swat.

Other less usual titles included Darbar Sahib, Dewan, Jam, Mehtar (unique to Chitral) and Mir (from Emir).

The Sikh princes concentrated at Punjab usually adopted titles when attaining princely rank. A title at a level of Maharaja was used.

There were also compound titles, such as (Maha)rajadhiraj, Raj-i-rajgan, often relics from an elaborate system of hierarchical titles under the Mughal emperors. For example, the addition of the adjective Bahadur (from Persian, literally meaning "brave") raised the status of the titleholder one level.

Furthermore, most dynasties used a variety of additional titles such as Varma in South India. This should not be confused with various titles and suffixes not specific to princes but used by entire (sub)castes. This is almost analogous to Singh title in North India.

Precedence and prestige

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2024) |

The actual importance of a princely state could not be read from the title of its ruler, which was usually granted (or at least recognized) as a favor, often in recognition for loyalty and services rendered to the British Raj. Although some titles were raised once or even repeatedly, there was no automatic updating when a state gained or lost real power. Princely titles were even awarded to holders of domains (mainly jagirs) and even taluqdars and zamindars, which were not states at all. Most of the zamindars who held princely titles were in fact erstwhile princely and royal states reduced to becoming zamindars by the British East India Company. Various sources give significantly different numbers of states and domains of the various types. Even in general, the definitions of titles and domains are clearly not well-established.

In addition to their titles, all princely rulers were eligible to be appointed to certain British orders of chivalry associated with India, the Most Exalted Order of the Star of India and the Most Eminent Order of the Indian Empire. Women could be appointed as "Knights" (instead of Dames) of these orders. Rulers entitled to 21-gun and 19-gun salutes were normally appointed to the highest rank, Knight Grand Commander of the Order of the Star of India.

Many Indian princes served in the British Army, the Indian Army, or in local guard or police forces, often rising to high ranks; some even served while on the throne. Many of these were appointed as an aide-de-camp, either to the ruling prince of their own house (in the case of relatives of such rulers) or to British monarchs. Many saw active service, both on the subcontinent and on other fronts, during both World Wars.

Apart from those members of the princely houses who entered military service and who distinguished themselves, a good number of princes received honorary ranks as officers in the British and British Indian Armed Forces. Those ranks were conferred based on several factors, including their heritage, lineage, gun-salute (or lack of one) as well as personal character or martial traditions. After the First and Second World Wars, the princely rulers of several of the major states, including Gwalior, Patiala, Nabha, Faridkort, Bikaner, Jaipur, Jodhpur, Jammu and Kashmir and Hyderabad, were given honorary general officer ranks as a result of their states' contributions to the war effort.

- Lieutenant/Captain/Flight Lieutenant or Lieutenant-Commander/Major/Squadron Leader (for junior members of princely houses or for minor princes)

- Commander/Lieutenant-Colonel/Wing Commander or Captain/Colonel/Group Captain (granted to princes of salute states, often to those entitled to 15-guns or more)

- Commodore/Brigadier/Air Commodore (conferred upon princes of salute states entitled to gun salutes of 15-guns or more)

- Major-General/Air Vice-Marshal (conferred upon princes of salute states entitled to 15-guns or more; conferred upon rulers of the major princely states, including Baroda, Kapurthala, Travancore, Bhopal and Mysore)

- Lieutenant-General (conferred upon the rulers of the largest and most prominent princely houses after the First and Second World Wars for their states' contributions to the war effort.)

- General (very rarely awarded; the Maharajas of Gwalior and Jammu & Kashmir were created honorary Generals in the British Army in 1877, the Maharaja of Bikaner was made one in 1937, and the Nizam of Hyderabad in 1941)[citation needed]

It was also not unusual for members of princely houses to be appointed to various colonial offices, often far from their native state, or to enter the diplomatic corps.

Salute states

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2024) |

The gun salute system was used to set unambiguously the precedence of the major rulers in the area in which the British East India Company was active, or generally of the states and their dynasties. As heads of state, certain princely rulers were entitled to be saluted by the firing of an odd number of guns between three and 21, with a greater number of guns indicating greater prestige. Generally, the number of guns remained the same for all successive rulers of a particular state, but individual princes were sometimes granted additional guns on a personal basis. Furthermore, rulers were sometimes granted additional gun salutes within their own territories only, constituting a semi-promotion. The states of all these rulers (about 120) were known as salute states.

After Indian Independence, the Maharana of Udaipur displaced the Nizam of Hyderabad as the most senior prince in India[citation needed], because Hyderabad State had not acceded to the new Dominion of India, and the style Highness was extended to all rulers entitled to 9-gun salutes. When the princely states had been integrated into the Indian Union, their rulers were promised continued privileges and an income (known as the Privy Purse) for their upkeep. Subsequently, when the Indian government abolished the Privy Purse in 1971, the entire princely order ceased to be recognized under Indian law, although many families continue to retain their social prestige informally. Some descendants of the rulers remain prominent in regional or national politics, diplomacy, business, and high society.

At the time of Indian independence, only five rulers – the Nizam of Hyderabad, the Maharaja of Mysore, the Maharaja of Jammu and Kashmir state, the Maharaja Scindia of Gwalior and the Maharaja Gaekwad of Baroda – were entitled to a 21-gun salute. Six more[citation needed] – the Nawab of Bhopal, the Maharaja Holkar of Indore, the Maharaja of Bharatpur[citation needed], the Maharana of Udaipur, the Maharaja of Kolhapur, the Maharaja of Patiala[citation needed] and the Maharaja of Travancore – were entitled to 19-gun salutes. The most senior princely ruler was the Nizam of Hyderabad, who was entitled to the unique style Exalted Highness and 21-gun salute.[18] Other princely rulers entitled to salutes of 11 guns (soon 9 guns too) or more were entitled to the style Highness. No special style was used by rulers entitled to lesser gun salutes.

As paramount ruler, and successor to the Mughals, the British King-Emperor of India, for whom the style of Majesty was reserved, was entitled to an 'imperial' 101-gun salute—in the European tradition also the number of guns fired to announce the birth of an heir (male) to the throne.

Non-salute states

[edit]

There was no strict correlation between the levels of the titles and the classes of gun salutes, the real measure of precedence, but merely a growing percentage of higher titles in classes with more guns.

As a rule the majority of gun-salute princes had at least nine, with numbers below that usually the prerogative of Arab Sheikhs of the Aden protectorate, also under British protection.

There were many so-called non-salute states of lower prestige. Since the total of salute states was 117 and there were more than 500 princely states, most rulers were not entitled to any gun salute. Not all of these were minor rulers – Surguja State, for example, was both larger and more populous than Karauli State, but the Maharaja of Karauli was entitled to a 17-gun salute and the Maharaja of Surguja was not entitled to any gun salute at all.[19][20][21]

A number of princes, in the broadest sense of the term, were not even acknowledged as such.[example needed] On the other hand, the dynasties of certain defunct states were allowed to keep their princely status – they were known as political pensioners, such as the Nawab of Oudh. There were also certain estates of British India which were rendered as political saranjams, having equal princely status.[22] Though none of these princes were awarded gun salutes, princely titles in this category were recognised as a form of vassals of salute states, and were not even in direct relation with the paramount power.

Largest princely states by area

[edit]| Name of princely state | Area in square miles | Population in 1941 | Present State | Title, ethnicity, and religion of ruler | Gun-salute for ruler | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 84,471 | 4,021,616 | including Gilgit, Baltistan (Skardu), Ladakh, and Punch (mostly Muslim, with a sizeable Hindu and Buddhist minority) | Jammu & Kashmir and Ladakh in India | Maharaja, Dogra, Hindu | 21 | |

| 82,698 | 16,338,534 | (mostly Hindu with a sizeable Muslim minority) | Telangana, Maharashtra, Karnataka in India | Nizam, Turkic, Muslim | 21 | |

| 73,278 | 250,211 | (chiefly Muslim with a small Hindu minority) | Balochistan, Pakistan | Khan or Wali, Baloch, Muslim | 19 | |

| 36,071 | 2,125,000 | (mostly Hindu with a sizeable Muslim minority) | Rajasthan, India | Maharaja, Rathore, Hindu | 17 | |

| 29,458 | 7,328,896 | (Chiefly Hindu, with pockets of Muslim minority) | Karnataka, India | Wodeyar dynasty; Maharaja; Kannadiga; Hindu Kshattriya (Urs/Arasu in Kannada) | 21 | |

| 26,397 | 4,006,159 | (chiefly Hindu, with a sizeable Muslim minority) | Madhya Pradesh, India | Maharaja, Maratha, Hindu | 21 | |

| 23,317 | 936,218 | (chiefly Hindu, with a low Muslim minority) | Rajasthan, India | Maharaja, Rathore, Hindu | 17 | |

| 17,726 | 1,341,209 | (Chiefly Muslim, with a sizeable Hindu and Sikh minority) | Punjab, Pakistan | Nawab Amir, Abbasid, Muslim | 17 | |

| 16,100 | 76,255 | (Chiefly Hindu with a sizeable Muslim minority) | Rajasthan, India | Maharaja, Bhati, Hindu | 15 | |

| 15,601 | 2,631,775 | (Chiefly Hindu, with a sizeable Muslim population) | Rajasthan, India | Maharaja, Kachhwaha, Hindu | 17 | |

| 13,062 | 306,501 | (Chiefly Hindu, with a low Muslim population) | Chhattisgarh, India | Maharaja, Kakatiya - Bhanj, Hindu | - | |

Doctrine of lapse

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2024) |

A controversial aspect of East India Company rule was the doctrine of lapse, a policy under which lands whose feudal ruler died (or otherwise became unfit to rule) without a male biological heir (as opposed to an adopted son) would become directly controlled by the company and an adopted son would not become the ruler of the princely state. This policy went counter to Indian tradition where, unlike Europe, it was far more the accepted norm for a ruler to appoint his own heir.

The doctrine of lapse was pursued most vigorously by the Governor-General Sir James Ramsay, 10th Earl (later 1st Marquess) of Dalhousie. Dalhousie annexed seven states, including Awadh (Oudh), whose Nawabs he had accused of misrule, and the Maratha states of Nagpur, Jhansi, Satara, Sambalpur, and Thanjavur. Resentment over the annexation of these states turned to indignation when the heirlooms of the Maharajas of Nagpur were auctioned off in Calcutta. Dalhousie's actions contributed to the rising discontent amongst the upper castes which played a large part in the outbreak of the Indian mutiny of 1857. The last Mughal badshah (emperor), Bahadur Shah Zafar, whom many of the mutineers saw as a figurehead to rally around, was deposed following its suppression.

In response to the unpopularity of the doctrine, it was discontinued with the end of Company rule and the British Parliament's assumption of direct power over India in 1858.

Imperial governance

[edit]

By treaty, the British controlled the external affairs of the princely states absolutely. As the states were not British possessions, they retained control over their own internal affairs, subject to a degree of British influence which in many states was substantial.

By the beginning of the 20th century, relations between the British and the four largest states – Hyderabad, Mysore, Jammu and Kashmir, and Baroda – were directly under the control of the governor-general of India, in the person of a British resident. Two agencies, for Rajputana and Central India, oversaw twenty and 148 princely states respectively. The remaining princely states had their own British political officers, or Agents, who answered to the administrators of India's provinces. The agents of five princely states were then under the authority of Madras, 354 under Bombay, 26 of Bengal, two under Assam, 34 under Punjab, fifteen under the Central Provinces and Berar and two under the United Provinces.

The Chamber of Princes (Narender Mandal or Narendra Mandal) was an institution established in 1920 by a royal proclamation of the King-Emperor to provide a forum in which the rulers could voice their needs and aspirations to the government. It survived until the end of the British Raj in 1947.[23]

By the early 1930s, most of the princely states whose agencies were under the authority of India's provinces were organised into new Agencies, answerable directly to the governor-general, on the model of the Central India and Rajputana agencies: the Eastern States Agency, Punjab States Agency, Baluchistan Agency, Deccan States Agency, Madras States Agency and the Northwest Frontier States Agency. The Baroda Residency was combined with the princely states of northern Bombay Presidency into the Baroda, Western India and Gujarat States Agency. Gwalior was separated from the Central India Agency and given its own Resident, and the states of Rampur and Benares, formerly with Agents under the authority of the United Provinces, were placed under the Gwalior Residency in 1936. The princely states of Sandur and Banganapalle in Mysore Presidency were transferred to the agency of the Mysore Resident in 1939.

- Principal princely states in 1947

The native states in 1947 included five large states that were in "direct political relations" with the Government of India. For the complete list of princely states in 1947, see lists of princely states of India.

In direct relations with the central government

[edit]| Name of princely state | Area in square miles | Population in 1941 | Approximate revenue of the state (in hundred thousand rupees) | Title, ethnicity, and religion of ruler | Gun-salute for ruler | Designation of local political officer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13,866 | 3,343,477 (chiefly Hindu, with a sizeable Muslim population) | 323.26 | Maharaja, Maratha, Hindu | 21 | Resident at Baroda | |

| 82,698 | 16,338,534 (mostly Hindu with a sizeable Muslim minority) | 1582.43 | Nizam, Turkic, Muslim | 21 | Resident in Hyderabad | |

| 84,471 | 4,021,616 including Gilgit, Baltistan (Skardu), Ladakh, and Punch (mostly Muslim, with sizeable Hindu and Buddhist populations) | 463.95 | Maharaja, Dogra, Hindu | 21 | Resident in Jammu & Kashmir | |

| 29,458 | 7,328,896 (chiefly Hindu, with sizeable Muslim populations) | 1001.38 | Wodeyar (means Owner in Kannada) and Maharaja, Kannadiga, Hindu | 21 | Resident in Mysore | |

| 26,397 | 4,006,159 (chiefly Hindu, with a sizeable Muslim population) | 356.75 | Maharaja, Maratha, Hindu | 21 | Resident at Gwalior | |

| Total | 236,890 | 35,038,682 | 3727.77 | |||

Central India Agency, Gwalior Residency, Baluchistan Agency, Rajputana Agency, Eastern States Agency

| Name of princely state | Area in square miles | Population in 1941 | Approximate revenue of the state (in hundred thousand rupees) | Title, ethnicity, and religion of ruler | Gun-salute for ruler | Designation of local political officer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indore State | 9,341 | 1,513,966 (chiefly Hindu, with a sizeable Muslim population) | 304.9 | Maharaja, Maratha, Hindu | 19 (plus 2 local) | Resident at Indore |

| Bhopal | 6,924 | 785,322 (chiefly Hindu, with a sizeable Muslim population) | 119.82 | Nawab(m)/Begum(f), Afghan, Muslim | 19 (plus 2 local) | Political Agent in Bhopal |

| Rewah | 13,000 | 1,820,445 (chiefly Hindu, with a sizeable Muslim population) | 65 | Maharaja, Baghel Rajput, Hindu | 17 | Second largest state in Baghelkhand |

| 85 smaller and minor states (1941) | 22,995 (1901) | 2.74 million (chiefly Hindu, 1901) | 129 (1901) | |||

| Total | 77,395 (1901) | 8.51 million (1901) | 421 (1901) | |||

| Name of princely state | Area in square miles | Population in 1941 | Approximate revenue of the state (in hundred thousand rupees) | Title, ethnicity, and religion of ruler | Gun-salute for ruler | Designation of local political officer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cooch Behar | 1,318 | 639,898 (chiefly Hindu, with a sizeable Muslim population) | 91 | Maharaja, Koch (Kshattriya), Brahmo | 13 | Resident for the Eastern States |

| Tripura State | 4,116 | 513,010 (chiefly Vaishnavite, with a sizeable Sanamahi minority) | 54 | Maharaja, Tripuri, Vaishnavite (Kshattriya) | 13 | Resident for the Eastern States |

| Mayurbhanj State | 4,243 | 990,977 (chiefly Hindu) | 49 | Maharaja, Kshattriya, Hindu | 9 | Resident for the Eastern States |

| 39 smaller and minor states (1941) | 56,253 | 6,641,991 | 241.31 | |||

| Total | 65,930 | 8,785,876 | 435.31 | |||

Gwalior Residency (two states)

| Name of princely state | Area in square miles | Population in 1941 | Approximate revenue of the state (in hundred thousand rupees) | Title, ethnicity, and religion of ruler | Gun-salute for ruler | Designation of local political officer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rampur | 893 | 464,919 (chiefly Muslim, with a sizeable Hindu population in 1931) | 51 | Nawab, Jat,[32][33] Muslim | 15 | Political Agent at Rampur |

| Benares State | 875 | 391,165 (chiefly Hindu, 1931) | 19 | Maharaja, Bhumihar, Hindu | 13 (plus 2 local) | Political Agent at Benares |

| Total | 1,768 | 856,084 (1941, approx.) | 70 | |||

| Name of princely state | Area in square miles | Population in 1941 | Approximate revenue of the state (in hundred thousand rupees) | Title, ethnicity, and religion of ruler | Gun-salute for ruler | Designation of local political officer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Udaipur (Mewar) | 13,170 | 1,926,698 (chiefly Hindu and Bhil) | 107 | Maharana, Sisodia Rajput, Hindu | 19 (plus 2 personal) | Political Agent for the Mewar and Southern Rajputana States |

| Jaipur | 15,610 | 3,040,876 (chiefly Hindu) | 188.6 | Maharaja, Kachwaha Rajput, Hindu | 17 (plus 2 personal) | Political Agent at Jaipur |

| Jodhpur (Marwar) | 36,120 | 2,555,904 (chiefly Hindu) | 208.65 | Maharaja, Rathor Rajput, Hindu | 17 | Political Agent for the Western States of Rajputana |

| Bikaner | 23,181 | 1,292,938 (chiefly Hindu) | 185.5 | Maharaja, Rathor Rajput, Hindu | 17 | Political agent for the Western States of Rajputana |

| 17 salute states, 1 chiefship, 1 zamindari | 42,374 | 3.64 million (chiefly Hindu, 1901) | 155 (1901) | |||

| Total | 128,918 (1901) | 9.84 million (1901) | 320 (1901) | |||

| Name of princely state | Area in square miles | Population in 1941 | Approximate revenue of the state (in hundred thousand rupees) | Title, ethnicity, and religion of ruler | Gun-salute for ruler | Designation of local political officer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kalat | 73,278 | 250,211 (chiefly Muslim) | 21.3 | Khan or Wali, Baloch, Muslim | 19 | Political Agent in Kalat |

| Las Bela | 7,132 | 68,972 (chiefly Muslim) | 6.1 | Jam, Baloch, Muslim | Political Agent in Kalat | |

| Kharan | 14,210 | 33,763 (chiefly Muslim) | 2 | Nawab, Baloch, Muslim | Political Agent in Kalat | |

| Total | 94,620 | 352,946 | 29.4 | |||

Other states under provincial governments

Madras (5 states)

| Name of princely state | Area in square miles | Population in 1901 | Approximate revenue of the state (in hundred thousand rupees) | Title, ethnicity, and religion of ruler | Gun-salute for ruler | Designation of local political officer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Travancore | 7,091 | 2,952,157 (chiefly Hindu and Christian) | 100 | Maharaja, Kshatriya-Samanthan, Hindu | 21 (including two guns personal to the then ruler) | Resident in Travancore and Cochin |

| Cochin | 1,362 | 812,025 (chiefly Hindu and Christian) | 27 | Raja, Samanta-Kshatriya, Hindu | 17 | Resident in Travancore and Cochin |

| Pudukkottai | 1,100 | 380,440 (chiefly Hindu) | 11 | Raja, Kallar, Hindu | 11 | Collector of Trichinopoly (ex officio Political Agent) |

| 2 minor states (Banganapalle and Sandur) | 416 | 43,464 | 3 | |||

| Total | 9,969 | 4,188,086 | 141 | |||

Bombay (354 states)

| Name of princely state | Area in square miles | Population in 1901 | Approximate revenue of the state (in hundred thousand rupees) | Title, ethnicity, and religion of ruler | Gun-salute for ruler | Designation of local political officer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kolhapur | 2,855 | 910,011 (chiefly Hindu) | 48 | Maharaja", Chhtrapati "Maratha, Hindu | 19 | Political Agent for Kolhapur |

| Cutch | 7,616 | 488,022 (chiefly Hindu) | 20 | Maharao, Jadeja Rajput, Hindu | 17 | Political Agent in Cutch |

| Junagarh | 3,284 | 395,428 (chiefly Hindu with a sizeable Muslim population) | 27 | Nawab, Pathan, Muslim | 11 | Agent to the Governor in Kathiawar |

| Navanagar | 3,791 | 336,779 (chiefly Hindu) | 31 | Jam Sahib, Jadeja Rajput, Hindu | 11 | Agent to the Governor in Kathiawar |

| 349 other states | 42,165 | 4,579,095 | 281 | |||

| Total | 65,761 | 6,908,648 | 420 | |||

Central Provinces (15 states)

| Name of princely state | Area in square miles | Population in 1901 | Approximate revenue of the state (in hundred thousand rupees) | Title, ethnicity, and religion of ruler | Gun-salute for ruler | Designation of local political officer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kalahandi | 3,745 | 284,465 (chiefly Hindu) | 4 | Raja, Kshatriya, Hindu | 9 | Political Agent for the Chhattisgarh Feudatories |

| Bastar | 13,062 | 306,501 (chiefly animist) | 3 | Raja, Kshatriya, Hindu | Political Agent for the Chhattisgarh Feudatories | |

| 13 other states | 12,628 | 1,339,353 (chiefly Hindu) | 16 | 11 | ||

| Total | 29,435 | 1,996,383 | 21 | |||

Punjab (45 states)

| Name of princely state | Area in square miles | Population in 1941 | Approximate revenue of the state (in hundred thousand rupees) | Title, ethnicity, and religion of ruler | Gun-salute for ruler | Designation of local political officer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bahawalpur State | 16,434 | 1,341,209 (chiefly Muslim) | 335 | Nawab, Daudputra, Muslim | 17 | Political Agent for Phulkian States and Bahawalpur |

| Patiala State | 5,942 | 1,936,259 (chiefly Sikh) | 302.6 | Maharaja, Sikh | 17 (and 2 personal) | Political Agent for Phulkian States and Bahawalpur |

| Nabha State | 947 | 340,044 (chiefly Sikh) | 38.7 | Maharaja, Sikh | 13 (and 2 local) | Political Agent for Phulkian States and Bahawalpur |

| Jind State | 1,299 | 361,812 (chiefly Sikh) | 37.4 | Maharaja, Sikh | 13 (and 2 personal) | Political Agent for Phulkian States and Bahawalpur |

| Kapurthala State | 645 | 378,380 (chiefly Sikh) | 40.5 | Maharaja, Ahuluwalia, Sikh | 13 (and 2 personal) | Commissioner of the Jullundur Division (ex officio Political Agent) |

| Faridkot State | 638 | 199,283 (chiefly Sikh) | 22.7 | Raja, Sikh | 11 | Commissioner of the Jullundur Division (ex officio Political Agent) |

| Garhwal State | 4,500 | 397,369 (chiefly Hindu) | 26.9 | Maharaja, Rajput Hindu | 11 | Commissioner of Kumaun (ex officio Political Agent) |

| Khayrpur State | 6,050 | 305,387 (chiefly Muslim) | 15 (plus 2 local) | Mir, Talpur Baloch, Muslim | 37.8 | Political Agent for Khairpur |

| 25 other states | 12,661 (in 1901) | 1,087,614 (in 1901) | 30 (in 1901) | |||

| Total | 36,532 (in 1901) | 4,424,398 (in 1901) | 155 (in 1901) | |||

Assam (26 states)

| Name of princely state | Area in square miles | Population in 1941 | Approximate revenue of the state (in hundred thousand rupees) | Title, ethnicity, and religion of ruler | Gun-salute for ruler | Designation of local political officer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manipur | 270.3 | 512,069 (chiefly Hindu and animist) | 19 | Raja, Kshatriya, Hindu | 11 | Political Agent in Manipur |

| 25 Khasi States | 3,778 | 213,586 (chiefly Khasi and Christian) | ~1 (1941, approx.) | Deputy Commissioner, Khasi and Jaintia Hills | ||

| Total | 12,416 | 725,655 | 20 (1941; approx.) | |||

- Burma (52 states)

| Name of princely state | Area in square miles | Population in 1901 | Approximate revenue of the state (in hundred thousand rupees) | Title, ethnicity, and religion of ruler | Gun-salute for ruler | Designation of local political officer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hsipaw (Thibaw) | 5,086 | 105,000 (Buddhist) | 3 | Sawbwa, Shan, Buddhist | 9 | Superintendent, Northern Shan States |

| Kengtung | 12,000 | 190,000 (Buddhist) | 1 | Sawbwa, Shan, Buddhist | 9 | Superintendent Southern Shan States |

| Yawnghwe | 865 | 95,339 (Buddhist) | 2.13 | Sawbwa, Shan, Buddhist | 9 | Superintendent Southern Shan States |

| Möng Nai | 2,717 | 44,000 (Buddhist) | 0.5 | Sawbwa, Shan, Buddhist | Superintendent Southern Shan States | |

| 5 Karenni States | 3,130 | 45,795 (Buddhist and animist) | 0.035 | Sawbwa, Karenni, Buddhist | Superintendent Southern Shan States | |

| 44 other states | 42,198 | 792,152 (Buddhist and animist) | 8.5 | |||

| Total | 67,011 | 1,177,987 | 13.5 | |||

State military forces

[edit]The armies of the princely states were bound by many restrictions that were imposed by subsidiary alliances. They existed mainly for ceremonial use and for internal policing, although certain units designated as Imperial Service Troops, were available for service alongside the regular British Indian Army upon request by the British government.[45]

According to the Imperial Gazetteer of India vol. IV 1907, p. 85,

Since a chief can neither attack his neighbour nor fall out with a foreign nation, it follows that he needs no military establishment which is not required either for police purposes or personal display, or for cooperation with the Imperial Government. The treaty made with Gwalior in 1844, and the instrument of transfer given to Mysore in 1881, alike base the restriction of the forces of the State upon the broad ground of protection. The former explained in detail that unnecessary armies were embarrassing to the State itself and the cause of disquietude to others: a few months later a striking proof of this was afforded by the army of the Sikh Kingdom of Lahore. The British Government has undertaken to protect the dominions of the Native princes from invasion and even from rebellion within: its army is organised for the defence not merely of British India, but of all the possessions under the suzerainty of the King-Emperor.[46]

In addition, other restrictions were imposed:

The treaties with most of the larger States are clear on this point. Posts in the interior must not be fortified, factories for the production of guns and ammunition must not be constructed, nor may the subject of other States be enlisted in the local forces. ... They must allow the forces that defend them to obtain local supplies, to occupy cantonments or positions, and to arrest deserters; and in addition to these services they must recognise the Imperial control of the railways, telegraphs, and postal communications as essential not only to the common welfare but to the common defence.[47]

The Imperial Service Troops were routinely inspected by British army officers and had the same equipment as soldiers in the British Indian Army.[48] Although their numbers were relatively small, the Imperial Service Troops were employed in China and British Somaliland in the first decade of the 20th century, and later saw action in the First World War and Second World War .[48]

Political integration of princely states

[edit]In 1920, the Indian National Congress under the leadership of Mahatma Gandhi declared that attainment of swaraj for Indians was its goal. It asked "all the sovereign princes of India to establish full responsible government in their states". Gandhi assured the princes that the Congress would not intervene in the princely states internal affairs .[3] Congress reiterated their demand at 1928 Calcutta Congress, "This Congress assures the people of the Indian States of its sympathy with and support in their legitimate and peaceful struggle for the attainment of full responsible government in the States."[4]

Jawaharlal Nehru played a major role in pushing Congress to confront the princely states.[4] In his presidential address at Lahore session in 1929, Jawaharlal Nehru declared: "The Indian states cannot live apart from the rest of the (sic) India".[49] Nehru added he is "no believer in kings or princes" and that "the only people who have the right to determine the future of the States must be the people of these States. This Congress which claims self-determination cannot deny it to the people of the states."[4]

After the Congress's electoral victory in 1937 elections, protests, sometimes violent, and satyagrahas against the princely states were organised and were supported by the Congress's ministries. Gandhi fasted in Rajkot State to demand "full responsible government" and added that "the people" were "the real rulers of Rajkot under the paramountcy of the Congress". Gandhi termed this protest as struggle against "the disciplined hordes of the British empire". Gandhi proclaimed that the Congress had now every right to intervene in "the states which are the vassals of the British".[4] In 1937, Gandhi played a major role in formation of federation involving a union between British India and the princely states with an Indian central government.[50]

In 1939, Nehru challenged the existence of the princely states and added that "the states in modern India are anachronistic and do not deserve to exist."[4] In July 1946, Nehru pointedly observed that no princely state could prevail militarily against the army of independent India.[5]

Hindu Mahasabha took funding from the princely states and supported them to remain independent even after the independence of India. V. D. Savarkar particularly hailed the Hindu dominated states as the 'bedrock of Hindu power' and defended their despotic powers, referring to them as the 'citadels of organised Hindu power'. He particularly hailed the princely states such as Mysore State, Travancore, Oudh and Baroda State as 'progressive Hindu states'.[51][52]

The era of the princely states effectively ended with Indian independence in 1947; by 1950, almost all of the principalities had acceded to either the Dominion of India or the Dominion of Pakistan.[53] The accession process was largely peaceful, except in the cases of Jammu and Kashmir (whose ruler decided to accede to India following an invasion by Pakistan-based forces, resulting in a long-standing dispute between the two countries),[54] Hyderabad State (whose ruler opted for independence in 1947, followed a year later by the invasion and annexation of the state by India), Junagarh and its vassal Bantva Manavadar (whose rulers acceded to Pakistan, but were annexed by India),[55] and Kalat (whose ruler declared independence in 1947, followed in 1948 by the state's accession to Pakistan).[56][57][58]

India

[edit]At the time of Indian independence on 15 August 1947, India was divided into two sets of territories, the first being the territories of "British India", which were under the direct control of the India Office in London and the governor-general of India, and the second being the "princely states", the territories over which the Crown had suzerainty, but which were under the control of their hereditary rulers. In addition, there were several colonial enclaves controlled by France and Portugal. The integration of these territories into Dominion of India, that had been created by the Indian Independence Act 1947 by the British Parliament, was a declared objective of the Indian National Congress, which the Government of India pursued over the years 1947 to 1949. Through a combination of tactics, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel and V. P. Menon in the months immediately preceding and following the independence convinced the rulers of almost all of the hundreds of princely states to accede to India. In a speech in January 1948, Vallabhbhai Patel said:

As you are all aware, on the lapse of Paramountcy every Indian State became a separate independent entity and our first task of consolidating about 550 States was on the basis of accession to the Indian Dominion on three subjects. Barring Hyderabad and Junagadh all the states which are contiguous to India acceded to Indian Dominion. Subsequently, Kashmir also came in... Some Rulers who were quick to read the writing on the wall, gave responsible government to their people; Cochin being the most illustrious example. In Travancore, there was a short struggle, but there, too, the Ruler soon recognised the aspiration of his people and agreed to introduce a constitution in which all powers would be transferred to the people and he would function as a constitutional Ruler.[59]

Although this process successfully integrated the vast majority of princely states into India, it was not as successful in relation to a few states, notably the former princely state of Kashmir, whose Maharaja delayed signing the instrument of accession into India until his territories were under the threat of invasion by Pakistan, and the state of Hyderabad, whose ruler decided to remain independent and was subsequently defeated by the Operation Polo invasion.

Having secured their accession, Sardar Patel and V. P. Menon then proceeded, in a step-by-step process, to secure and extend the central government's authority over these states and to transform their administrations until, by 1956, there was little difference between the territories that had formerly been part of British India and those that had been princely states. Simultaneously, the Government of India, through a combination of diplomatic and economic pressure, acquired control over most of the remaining European colonial exclaves on the subcontinent. Fed up with the protracted and stubborn resistance of the Portuguese government; in 1961 the Indian Army invaded and annexed Portuguese India.[60] These territories, like the princely states, were also integrated into the Republic of India.

As the final step, in 1971, the 26th amendment[61] to the Constitution of India withdrew recognition of the princes as rulers, took away their remaining privileges, and abolished the remuneration granted to them by privy purses.

As per the terms of accession, the erstwhile Indian princes received privy purses (government allowances), and initially retained their statuses, privileges, and autonomy in internal matters during a transitional period which lasted until 1956. During this time, the former princely states were merged into unions, each of which was headed by a former ruling prince with the title of Rajpramukh (ruling chief), equivalent to a state governor.[62] In 1956, the position of Rajpramukh was abolished and the federations dissolved, the former principalities becoming part of Indian states. The states which acceded to Pakistan retained their status until the promulgation of a new constitution in 1956, when most became part of the province of West Pakistan; a few of the former states retained their autonomy until 1969 when they were fully integrated into Pakistan. The Indian government abolished the privy purses in 1971, followed by the government of Pakistan in 1972.[citation needed]

In July 1946, Jawaharlal Nehru pointedly observed that no princely state could prevail militarily against the army of independent India.[5] In January 1947, Nehru said that independent India would not accept the divine right of kings.[63] In May, 1947, he declared that any princely state which refused to join the Constituent Assembly would be treated as an enemy state.[64] There were officially 565 princely states when India and Pakistan became independent in 1947, but the great majority had contracted with the British viceroy to provide public services and tax collection. Only 21 had actual state governments, and only four were large (Hyderabad State, Mysore State, Jammu and Kashmir State, and Baroda State). They acceded to one of the two new independent countries between 1947 and 1949. All the princes were eventually pensioned off.[65]

Pakistan

[edit]During the period of the British Raj, there were four princely states in Balochistan: Makran, Kharan, Las Bela and Kalat. The first three acceded to Pakistan.[66][67][68][69] However, the ruler of the fourth princely state, the Khan of Kalat Ahmad Yar Khan, declared Kalat's independence as this was one of the options given to all princely states.[70] The state remained independent until it was acceded on 27 March 1948. The signing of the Instrument of Accession by Ahmad Yar Khan, led his brother, Prince Abdul Karim, to revolt against his brother's decision in July 1948, causing an ongoing and still unresolved insurgency.[71]

Bahawalpur from the Punjab Agency joined Pakistan on 5 October 1947. The princely states of the North-West Frontier States Agencies. included the Dir Swat and Chitral Agency and the Deputy Commissioner of Hazara acting as the Political Agent for Amb and Phulra. These states joined Pakistan on independence from the British.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]- Flags of Indian princely states

- Political integration of India

- List of princely states of British India (by region)

- List of Indian monarchs

- Praja Mandal

- Salute state

- Indian feudalism

- Indian honorifics

- Ghatwals and Mulraiyats

- Jagirdar

- List of Maratha dynasties and states

- List of Rajput dynasties and states

- Maratha Empire

- List of Jat dynasties and states

- Oudh Bequest

- Rajputana

- Zamindar

References

[edit]- ^ Ramusack 2004, pp. 85 Quote: "The British did not create the Indian princes. Before and during the European penetration of India, indigenous rulers achieved dominance through the military protection they provided to dependents and their skill in acquiring revenues to maintain their military and administrative organizations. Major Indian rulers exercised varying degrees and types of sovereign powers before they entered treaty relations with the British. What changed during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries is that the British increasingly restricted the sovereignty of Indian rulers. The Indian Company set boundaries; it extracted resources in the form of military personnel, subsidies or tribute payments, and the purchase of commercial goods at favorable prices, and limited opportunities for other alliances. From the 1810s onwards as the British expanded and consolidated their power, their centralized military despotism dramatically reduced the political options of Indian rulers." (p. 85)

- ^ Ramusack 2004, p. 87 Quote: "The British system of indirect rule over Indian states ... provided a model for the efficient use of scarce monetary and personnel resources that could be adopted to imperial acquisitions in Malaya and Africa."

- ^ a b Sisson, Richard; Wolpert, Stanley (2018). Congress and Indian Nationalism: The Pre-Independence Phase. University of California Press. p. 381. ISBN 978-0-520-30163-4. Retrieved 14 August 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g Purushotham, S. (2021). From Raj to Republic: Sovereignty, Violence, and Democracy in India. South Asia in Motion. Stanford University Press. p. 40. ISBN 978-1-5036-1455-0. Retrieved 11 August 2024.

- ^ a b c Menon, Shivshankar (20 April 2021). India and Asian Geopolitics: The Past, Present. Brookings Institution Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-670-09129-4.

- ^ Bhargava, R. P. (1991). The Chamber of Princes. Northern Book Centre. pp. 312–323. ISBN 978-81-7211-005-5.

- ^ Markovits, Claude (2004). A history of modern India, 1480–1950. Anthem Press. pp. 386–409. ISBN 978-1-84331-004-4.

- ^ The India Office and Burma Office List: 1945. Harrison & Sons, Ltd. 1945. pp. 33–37.

- ^ Zubrzycki, John (2024). Dethroned. Oxford University Press. p. 41. ISBN 978-1-80526-053-0.

Princely States at the time of Indian independence owed their existence to the slow collapse of the Mughal Empire following the death of Aurangzeb in 1707. Centuries of foreign domination meant that many of the rulers who carved out their own states were outsiders. The Nizams of Hyderabad were of Turkoman stock. Bhopal was established by one of Aurangzeb's Afghan generals. Rampurs first ruler, Nawab Faizullah Khan, was a Pashtun. Tonk in present day Rajasthan was founded by Pindari freebooters. The seaboard state of Janjira was the creation of an Abysinnian pirate. Among the Hindu kingdoms, most of the rulers were Kshatriya. Only the Rajput states and a scattering of South Indian kingdoms could trace their lineage to the pre-Mughal period.

- ^ "Dubai: When the glittering city and other Gulf states almost became part of India". www.bbc.com. 21 June 2025. Retrieved 26 June 2025.

- ^ Dalrymple, Sam (19 June 2025). Shattered Lands: Five Partitions and the Making of Modern Asia (1 ed.). London: HarperCollins Publishers. ISBN 9780008466831.

- ^ Interpretation Act 1889 (52 & 53 Vict. c. 63), s. 18

- ^ 1. Imperial Gazetteer of India, volume IV, published under the authority of the Secretary of State for India-in-Council, 1909, Oxford University Press. page 5. Quote: "The history of British India falls, as observed by Sir C. P. Ilbert in his Government of India, into three periods. From the beginning of the seventeenth century to the middle of the eighteenth century the East India Company is a trading corporation, existing on the sufferance of the native powers and in rivalry with the merchant companies of Holland and France. During the next century the Company acquires and consolidates its dominion, shares its sovereignty in increasing proportions with the Crown, and gradually loses its mercantile privileges and functions. After the mutiny of 1857 the remaining powers of the Company are transferred to the Crown, and then follows an era of peace in which India awakens to new life and progress." 2. The Statutes: From the Twentieth Year of King Henry the Third to the ... by Robert Harry Drayton, Statutes of the Realm – Law – 1770 Page 211 (3) "Save as otherwise expressly provided in this Act, the law of British India and of the several parts thereof existing immediately before the appointed ..." 3. Edney, M. E. (1997) Mapping an Empire: The Geographical Construction of British India, 1765–1843, University of Chicago Press. 480 pages. ISBN 978-0-226-18488-3 4. Hawes, C.J. (1996) Poor Relations: The Making of a Eurasian Community in British India, 1773–1833. Routledge, 217 pages. ISBN 0-7007-0425-6.

- ^ Imperial Gazetteer of India vol. II 1908, pp. 463, 470 Quote1: "Before passing on to the political history of British India, which properly begins with the Anglo-French Wars in the Carnatic, ... (p. 463)" Quote2: "The political history of the British in India begins in the eighteenth century with the French Wars in the Carnatic. (p.471)"

- ^ a b Imperial Gazetteer of India vol. IV 1907, p. 60

- ^ Great Britain. Indian Statutory Commission; Viscount John Allsebrook Simon Simon (1930). Report of the Indian Statutory Commission ... H.M. Stationery Office. Retrieved 9 June 2012.

- ^ All India reporter. D.V. Chitaley. 1938. Retrieved 9 June 2012.

- ^ "King of all rewinds". The Week.

- ^ Lethbridge, Sir Roper (1900). The Golden Book of India. A Genealogical and Biographical Dictionary of the Ruling Princes, Chiefs, Nobles, and Other Personages, Titled Or Decorated, of the Indian Empire. With an Appendix for Ceylon. S. Low, Marston & Company. p. 132.

- ^ Office, Great Britain India (1902). The India List and India Office List for ... Harrison and Sons. p. 172.

- ^ Hooja, Rima (2006). A History of Rajasthan. Rupa & Company. p. 856. ISBN 978-81-291-0890-6.

- ^ Govindlal Dalsukhbhai Patel (1957). The land problem of reorganized Bombay state. N. M. Tripathi. Retrieved 9 June 2012.

- ^ Vapal Pangunni Menon (1956) The Story of the Integration of the Indian States, Macmillan Co., pp. 17–19

- ^ a b Imperial Gazetteer of India vol. IV 1907, p. 92

- ^ "Mysore", Indian States and Agencies, The Statesman's Year Book 1947, pg 173, Macmillan & Co.

- ^ "Jammu and Kashmir", Indian States and Agencies, The Statesman's Year Book 1947, pg 171, Macmillan & Co.

- ^ "Hyderabad", Indian States and Agencies, The Statesman's Year Book 1947, pg 170, Macmillan & Co.

- ^ a b Imperial Gazetteer of India vol. IV 1907, p. 93

- ^ "Central India Agency", Indian States and Agencies, The Statesman's Year Book 1947, pg 168, Macmillan & Co.

- ^ "Eastern States", Indian States and Agencies, The Statesman's Year Book 1947, pg 168, Macmillan & Co.

- ^ "Gwalior Residency", Indian States and Agencies, The Statesman's Year Book 1947, pg 170, Macmillan & Co.

- ^ Gupta, Hari Ram (1999) [1980]. History of the Sikhs. Vol. III: Sikh Domination of the Mughal Empire (1764–1803) (2nd rev. ed.). Munshiram Manoharlal. p. 11. ISBN 978-81-215-0213-9. OCLC 165428303. "The real founder of the Rohilla power was Ali Muhammad, from whom sprang the present line of the Nawabs of Rampur. Originally a Hindu Jat, who was taken prisoner when a young boy by Daud in one of his plundering expeditions, at village Bankauli in the parganah of Chaumahla, and was converted to Islam and adopted by him."

- ^ Khan, Iqbal Ghani (2002). "Technology and the Question of Elite Intervention in Eighteenth-Century North India". In Barnett, Richard B. (ed.). Rethinking Early Modern India. Manohar Publishers & Distributors. p. 271. ISBN 978-81-7304-308-6. "Thus we witness the Ruhelas accepting an exceptionally talented non-Afghan, an adopted Jat boy, as their nawab, purely on the basis of his military leadership; ..."

- ^ Imperial Gazetteer of India vol. IV 1907, pp. 94–95

- ^ "Rajputana", Indian States and Agencies, The Statesman's Year Book 1947, pg 175, Macmillan & Co.

- ^ a b Imperial Gazetteer of India vol. IV 1907, p. 96

- ^ "Baluchistan States", Indian States and Agencies, The Statesman's Year Book 1947, pg 160, Macmillan & Co.

- ^ Imperial Gazetteer of India vol. IV 1907, p. 97

- ^ Imperial Gazetteer of India vol. IV 1907, p. 102

- ^ Imperial Gazetteer of India vol. IV 1907, p. 100

- ^ "Punjab States", Indian States and Agencies, The Statesman's Year Book 1947, pg 174, Macmillan & Co.

- ^ Imperial Gazetteer of India vol. IV 1907, p. 103

- ^ "Assam States", Indian States and Agencies, The Statesman's Year Book 1947, pg 160, Macmillan & Co.

- ^ Imperial Gazetteer of India vol. IV 1907, p. 101

- ^ Lt. Gen. Sir George MacMunn, page 198 "The Armies of India", ISBN 0-947554-02-5

- ^ Imperial Gazetteer of India vol. IV 1907, p. 85

- ^ Imperial Gazetteer of India vol. IV 1907, pp. 85–86

- ^ a b Imperial Gazetteer of India vol. IV 1907, p. 87

- ^ Phadnis, Urmila (1968). Towards the Integration of Indian States, 1919-1947. Thesis Phil. Banaras Hindu University. Asia Publishing House. p. 90. ISBN 978-0-210-31180-6. Retrieved 14 August 2023.

- ^ Singh, R. (2017). Gandhi and the Nobel Peace Prize. Taylor & Francis. p. 4. ISBN 978-1-351-03612-2. Retrieved 14 August 2023.

- ^ Bapu, P. (2013). Hindu Mahasabha in Colonial North India, 1915-1930: Constructing Nation and History. Online access with subscription: Proquest Ebook Central. Routledge. pp. 32–33. ISBN 978-0-415-67165-1. Retrieved 12 October 2024.

- ^ Chhibber, P.K.; Verma, R. (2018). Ideology and Identity: The Changing Party Systems of India. Oxford University Press. p. 248. ISBN 978-0-19-062390-6. Retrieved 12 October 2024.

- ^ Ravi Kumar Pillai of Kandamath in the Journal of the Royal Society for Asian Affairs, pages 316–319 https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03068374.2016.1171621

- ^ Bajwa, Kuldip Singh (2003). Jammu and Kashmir War, 1947–1948: Political and Military Perspectiv. New Delhi: Hari-Anand Publications Limited. ISBN 978-81-241-0923-6.

- ^ Aparna Pande (16 March 2011). Explaining Pakistan's Foreign Policy: Escaping India. Taylor & Francis. pp. 31–. ISBN 978-1-136-81893-6.

- ^ Jalal, Ayesha (2014), The Struggle for Pakistan: A Muslim Homeland and Global Politics, Harvard University Press, p. 72, ISBN 978-0-674-74499-8: "Equally notorious was his high-handed treatment of the state of Kalat, whose ruler was made to accede to Pakistan on threat of punitive military action."

- ^ Samad, Yunas (2014). "Understanding the insurgency in Balochistan". Commonwealth & Comparative Politics. 52 (2): 293–320. doi:10.1080/14662043.2014.894280. S2CID 144156399.: "When Mir Ahmed Yar Khan dithered over acceding the Baloch-Brauhi confederacy to Pakistan in 1947 the centre's response was to initiate processes that would coerce the state joining Pakistan. By recognising the feudatory states of Las Bela, Kharan and the district of Mekran as independent states, which promptly merged with Pakistan, the State of Kalat became land locked and reduced to a fraction of its size. Thus Ahmed Yar Khan was forced to sign the instrument of accession on 27 March 1948, which immediately led to the brother of the Khan, Prince Abdul Karim raising the banner of revolt in July 1948, starting the first of the Baloch insurgencies."

- ^ Harrison, Selig S. (1981), In Afghanistan's Shadow: Baluch Nationalism and Soviet Temptations, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, p. 24, ISBN 978-0-87003-029-1: "Pakistani leaders summarily rejected this declaration, touching off a nine-month diplomatic tug of war that came to a climax in the forcible annexation of Kalat.... it is clear that Baluch leaders, including the Khan, were bitterly opposed to what happened."

- ^ R. P. Bhargava (1992) The Chamber of Princes, p. 313

- ^ Praval, Major K.C. (2009). Indian Army after Independence. New Delhi: Lancer. p. 214. ISBN 978-1-935501-10-7.

- ^ "The Constitution (26 Amendment) Act, 1971", indiacode.nic.in, Government of India, 1971, archived from the original on 6 December 2011, retrieved 9 November 2011

- ^ Wilhelm von Pochhammer, India's road to nationhood: a political history of the subcontinent (1982) ch 57

- ^ Lumby, E. W. R. 1954. The Transfer of Power in India, 1945–1947. London: George Allen & Unwin. p. 228

- ^ Tiwari, Aaditya (30 October 2017). "Sardar Patel – Man who United India". Press Information Bureau.

- ^ Wilhelm von Pochhammer, India's road to nationhood: a political history of the subcontinent (1981) ch 57

- ^ Pervaiz I Cheema; Manuel Riemer (22 August 1990). Pakistan's Defence Policy 1947–58. Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 60–. ISBN 978-1-349-20942-2.

- ^ Farhan Hanif Siddiqi (2012). The Politics of Ethnicity in Pakistan: The Baloch, Sindhi and Mohajir Ethnic Movements. Routledge. pp. 71–. ISBN 978-0-415-68614-3.

- ^ T.V. Paul (February 2014). The Warrior State: Pakistan in the Contemporary World. OUP USA. pp. 133–. ISBN 978-0-19-932223-7.

- ^ Bangash, Y. K. (2015), "Constructing the state: Constitutional integration of the princely states of Pakistan", in Roger D. Long; Gurharpal Singh; Yunas Samad; Ian Talbot (eds.), State and Nation-Building in Pakistan: Beyond Islam and Security, Routledge, pp. 82–, ISBN 978-1-317-44820-4

- ^ Nicholas Schmidle (2 March 2010). To Live or to Perish Forever: Two Tumultuous Years in Pakistan. Henry Holt and Company. pp. 86–. ISBN 978-1-4299-8590-1.

- ^ Syed Farooq Hasnat (26 May 2011). Global Security Watch—Pakistan. ABC-CLIO. pp. 94–. ISBN 978-0-313-34698-9.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bangash, Yaqoob Khan (2016). "A Princely Affair: The Accession and Integration of the Princely States of Pakistan, 1947–1955". Oxford University Press Pakistan. ISBN 978-0-19-940736-1

- Bhagavan, Manu. "Princely States and the Hindu Imaginary: Exploring the Cartography of Hindu Nationalism in Colonial India" Journal of Asian Studies, (Aug 2008) 67#3 pp 881–915 in JSTOR

- Bhagavan, Manu. Sovereign Spheres: Princes, Education and Empire in Colonial India (2003)

- Copland, Ian (2002), Princes of India in the Endgame of Empire, 1917–1947, (Cambridge Studies in Indian History & Society). Cambridge and London: Cambridge University Press. Pp. 316, ISBN 978-0-521-89436-4.

- Ernst, W. and B. Pati, eds. India's Princely States: People, Princes, and Colonialism (2007)

- Harrington, Jack (2010), Sir John Malcolm and the Creation of British India, Chs. 4 & 5., New York: Palgrave Macmillan., ISBN 978-0-230-10885-1

- Jeffrey, Robin. People, Princes and Paramount Power: Society and Politics in the Indian Princely States (1979) 396pp

- Kooiman, Dick. Communalism and Indian Princely States: Travancore, Baroda & Hyderabad in the 1930s (2002), 249pp

- Markovits, Claude (2004). "ch 21: "Princely India (1858–1950)". A history of modern India, 1480–1950. Anthem Press. pp. 386–409. ISBN 978-1-84331-152-2.

- Ramusack, Barbara (2004), The Indian Princes and their States, The New Cambridge History of India, Cambridge and London: Cambridge University Press. Pp. 324, ISBN 978-0-521-03989-5

- Pochhammer, Wilhelm von India's Road to Nationhood: A Political History of the Subcontinent (1973) ch 57 excerpt

- Zutshi, Chitralekha (2009). "Re-visioning princely states in South Asian historiography: A review". Indian Economic & Social History Review. 46 (3): 301–313. doi:10.1177/001946460904600302. S2CID 145521826.

Gazetteers

[edit]- Imperial Gazetteer of India vol. II (1908), The Indian Empire, Historical, Published under the authority of His Majesty's Secretary of State for India in Council, Oxford at the Clarendon Press. Pp. xxxv, 1 map, 573. online

- Imperial Gazetteer of India vol. III (1907), The Indian Empire, Economic (Chapter X: Famine, pp. 475–502, Published under the authority of His Majesty's Secretary of State for India in Council, Oxford at the Clarendon Press. Pp. xxxvi, 1 map, 520. online

- Imperial Gazetteer of India vol. IV (1907), The Indian Empire, Administrative, Published under the authority of His Majesty's Secretary of State for India in Council, Oxford at the Clarendon Press. Pp. xxx, 1 map, 552. online

External links

[edit]- Sir Roper Lethbridge (1893). The Golden Book of India: A Genealogical and Biographical Dictionary of the Ruling Princes, Chiefs, Nobles, and Other Personages, Titled or Decorated, of the Indian Empire (Full text). Macmillan And Co., New York.

- Exhaustive lists of rulers and heads of government, and some biographies.

- India, Order Book, released as part of a response from Passport Office, UK to a request made using WhatDoTheyKnow, accessed 17 October 2023.

Princely state

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Characteristics

Legal and Political Status

Princely states held a semi-sovereign legal status under British paramountcy, functioning as protectorates or vassal territories rather than direct colonies, with internal administration left to native rulers while external sovereignty was subordinated to the British Crown.[9] This arrangement covered approximately 562 states by 1930, encompassing diverse polities from expansive kingdoms like Hyderabad to petty principalities.[9] The doctrine of paramountcy, which crystallized around 1818 after the Third Anglo-Maratha War, positioned British authority as supreme, overriding state decisions in foreign affairs, defense, and succession without explicit treaty codification in every case.[9][10] Relations were formalized through bilateral treaties and subsidiary alliances, such as the 1798 agreement with Hyderabad requiring British troops in exchange for territorial concessions and the 1799 treaty with Mysore stipulating similar protective obligations.[10] These instruments preserved rulers' domestic prerogatives, including taxation, justice, and law-making, but mandated consultation with British Residents—diplomatic agents posted in key states—who enforced compliance and mediated disputes.[10] Following the Indian Rebellion of 1857 and the Government of India Act 1858, paramountcy transferred from the East India Company to the Crown, with the Viceroy assuming direct oversight, though interventions in internal governance remained selective to maintain stability.[10] Politically, princely rulers enjoyed hereditary titles and privileges, including gun salutes denoting rank, but lacked representation in British India's legislative councils; their influence was channeled through advisory mechanisms like the Chamber of Princes.[9] Established by King-Emperor George V's proclamation in 1920 as part of the Montagu-Chelmsford Reforms, this body convened annually under the Viceroy's presidency, allowing rulers to voice concerns on policy but without binding authority or veto power.[11] This consultative role underscored the states' subordinate yet shielded position, where British paramountcy shielded them from external threats while curtailing independent diplomacy.[10] Sovereignty was treated as divisible, with rulers retaining internal legitimacy but acknowledging British overlordship in international contexts, as affirmed in legal precedents like the 1856 Tanjore case.[9]Rulers, Titles, and Hereditary Rights

The rulers of princely states were indigenous monarchs who retained sovereignty over internal affairs while acknowledging British paramountcy. These rulers held titles derived from pre-colonial traditions, such as maharaja or raja for Hindu sovereigns and nawab, nizam, or beglarbegi for Muslim ones, reflecting their historical legitimacy and cultural heritage.[12] The British recognized these titles as hereditary, ensuring continuity unless overridden by specific policies like the Doctrine of Lapse prior to 1858.[13] Hereditary rights to succession followed patrilineal primogeniture in most states, with the eldest legitimate son inheriting the throne upon the ruler's death. In cases of childless rulers, adoption of a male heir from a noble family was a common practice to preserve dynastic continuity, a right that the East India Company sometimes challenged under lapse policies but which was formalized post-1857. Following the Indian Rebellion of 1857, Viceroy Lord Canning issued sanads (royal grants) to rulers, confirming full hereditary succession rights and the privilege of adoption without British veto, with approximately 150 such certificates issued by 1862 to legitimize adopted heirs across major states.[12][14] This policy shift aimed to secure loyalty by protecting dynastic lines, though minor states without sanads faced potential lapse if no natural heir existed.[15] Titles carried hierarchical prestige, often denoted by gun salutes ranging from 21 guns for premier states like Hyderabad, Mysore, and Baroda to 9 guns for lesser ones, symbolizing the ruler's status and proximity to the paramount power. Rulers of 21-gun salute states, numbering around five major entities, received the highest honors, including personal salutes even when traveling, and were styled His Highness with styles like Maharaja Maharaj or Nizam-ul-Mulk.[16] Lower-tier rulers held local titles without personal salutes but retained hereditary privileges within their domains. These distinctions, fixed by British agreements from the mid-19th century, reinforced a stratified order among the over 560 princely states, with salutes hereditary unless revoked for misconduct.[17]Historical Origins

Pre-Colonial Foundations

The pre-colonial foundations of princely states originated in the decentralized political landscape of ancient and early medieval India, where hereditary rulers governed semi-autonomous territories amid cycles of imperial unification and fragmentation. Following the decline of centralized empires like the Mauryas (322–185 BCE) and Guptas (c. 320–550 CE), the subcontinent devolved into a mosaic of regional kingdoms and chiefdoms, with local dynasties asserting control over land and resources through customary rights and military prowess. This structure emphasized rajadharma, the dharma of kingship, wherein rulers maintained legitimacy via protection of subjects, collection of tribute, and ritual sovereignty, often without rigid bureaucratic centralization.[7] Central to this system was the samanta framework, a hierarchical vassalage that gained prominence from the Gupta era onward, involving land assignments (bhoga or agrahara) to subordinates in exchange for loyalty, military aid, and revenue shares. Samantas, as feudatory lords, operated with considerable internal autonomy, managing justice, taxation, and defense while acknowledging a paramount sovereign through periodic homage and campaigns; this arrangement persisted across north and south India, fostering resilience among smaller polities against larger threats. By the early medieval period (c. 600–1200 CE), such dynamics underpinned the proliferation of principalities, as evidenced in inscriptions detailing obligations like troop provision during imperial needs.[18][19] In northern and western India, the emergence of warrior clans, particularly Rajputs from the 7th century CE, solidified these foundations, with dynasties establishing enduring seats of power amid invasions and power vacuums. Clans like the Pratiharas, Chauhans, and Guhilas founded kingdoms in Rajasthan and Gujarat, tracing lineages to solar or lunar Vedic origins and defending territories through fortified strongholds and cavalry-based warfare; for instance, the Guhila line claimed establishment in Mewar by the mid-6th century, evolving into a model of localized sovereignty. These pre-Mughal entities, numbering in the hundreds, provided the genealogical and institutional continuity for many later princely states, prioritizing martial ethos and agrarian extraction over expansive conquest.[7][20]Evolution Under Mughal and Regional Powers

The Mughal Empire's administrative framework provided the initial structure for many entities that later became princely states, primarily through the mansabdari system instituted by Akbar in 1571. This system ranked nobles (mansabdars) based on their zat (personal status) and sawar (cavalry maintenance) obligations, granting them revenue rights over jagirs in exchange for military service and loyalty to the emperor.[21] Over time, particularly among Rajput clans allied via marriages and service, these assignments evolved into hereditary domains, fostering semi-autonomous rule under nominal imperial oversight.[22] Aurangzeb's death in 1707 accelerated the empire's fragmentation, as weakened successors faced rebellions and invasions, allowing subahdars and zamindars to withhold tribute and assert independence while often retaining Mughal titles for legitimacy.[23] Successor states emerged prominently: Murshid Quli Khan established effective control in Bengal by 1717 as its diwan; Saadat Khan founded the Nawabi of Awadh in 1722; and Nizam-ul-Mulk Asaf Jah I consolidated Hyderabad in the Deccan by 1724 after defeating rivals.[24] These polities replicated Mughal hierarchies, incorporating subordinate jagirdars and local chiefs who managed internal affairs with reduced central interference.[25] Regional powers further molded this evolving system. The Maratha Confederacy, expanding from the western Deccan after Shivaji's era, imposed chauth—a levy of one-quarter of anticipated revenue—on territories in Gujarat, Malwa, and beyond to avert plunder, effectively establishing tributary relations with Rajput and other local rulers.[26] States like Jaipur, Jodhpur, and Udaipur, previously Mughal vassals, navigated these dynamics by paying Maratha tribute while preserving hereditary governance and military forces.[27] In Punjab, Sikh misls coalesced into principalities amid Afghan incursions, exemplifying how power vacuums birthed resilient local autonomies. By the late 18th century, this mosaic of overlords and subordinates—characterized by fluid alliances, warfare, and tribute extraction—had solidified numerous de facto independent realms, primed for reconfiguration under emerging European influence.[28]Establishment of British Paramountcy

Subsidiary Alliances and Expansion

The Subsidiary Alliance system, introduced by Governor-General Richard Wellesley in 1798, served as a diplomatic instrument for the British East India Company to extend paramountcy over Indian princely states without immediate territorial annexation. Under its terms, a ruler ceding external sovereignty accepted a British subsidiary force for protection, bore the maintenance costs of these troops—either through fixed subsidies or ceded territories—and dismissed European officers from their service while prohibiting employment of non-British foreigners without Company approval; in exchange, the British guaranteed defense against external threats and forbade the ruler from forming alliances with other powers. [29] [30] This arrangement effectively subordinated the state's foreign policy and military autonomy to British oversight, with a resident appointed to the court to enforce compliance, laying the groundwork for the indirect rule characteristic of princely states. [31] The policy's inaugural application occurred with the Nizam of Hyderabad in September 1798, where Ali Khan Asaf Jah II agreed to disband French mercenaries, cede territories, and host a British brigade funded by annual subsidies equivalent to the force's upkeep. [30] Subsequent adoptions accelerated British expansion: Mysore accepted in 1799 following the defeat of Tipu Sultan in the Fourth Anglo-Mysore War, ceding half its territory to cover subsidiary expenses; Tanjore followed in October 1799; Awadh in November 1801, under pressure yielding significant lands including Allahabad and Farrukhabad; and the Peshwa Baji Rao II of the Maratha Confederacy in December 1802 after the Treaty of Bassein, which triggered the Second Anglo-Maratha War. [30] [32] By 1805, additional states like the Bhonsle Rajas of Berar and Scindia of Gwalior had acceded, often amid military coercion or fiscal duress, transforming fragmented Indian polities into a network of dependent allies comprising over 40% of the subcontinent's territory under British influence. [31] This mechanism facilitated rapid British territorial and political expansion during Wellesley's tenure (1798–1805), as non-compliant states faced invasion—evident in conflicts with Mysore (1799) and Marathas (1803–1805)—while compliant ones incurred unsustainable debts from subsidizing British garrisons, enabling later interventions via policies like the Doctrine of Lapse. [33] Economically, the system's tribute demands strained princely treasuries, fostering dependency that preserved nominal sovereignty but eroded effective independence, as rulers lost agency over diplomacy and defense; for instance, Hyderabad's subsidies escalated from 7.2 million rupees annually by 1800, compelling further cessions. [29] Despite offers of security against rivals, the alliances prioritized British strategic consolidation over mutual benefit, converting potential adversaries into subordinated entities and preempting French or other European encroachments during the Napoleonic era. [31] By establishing a web of treaties, the Subsidiary Alliance delineated princely states as semi-sovereign entities under British suzerainty, where internal administration persisted under hereditary rulers but external relations and paramount interests deferred to Company arbitration; violations, such as secret pacts or unpaid subsidies, invited deposition or absorption, as seen in escalating Maratha submissions post-1802. [34] This framework, while averting outright conquest in many cases, systematically expanded British dominion from coastal enclaves to interior highlands, subsuming over 500 princely entities by the mid-19th century and solidifying the Raj's hierarchical control. [10]Doctrine of Lapse and Territorial Annexations

The Doctrine of Lapse was an annexation policy implemented by the British East India Company under Governor-General James Broun-Ramsay, 1st Marquess of Dalhousie, from 1848 to 1856, targeting princely states lacking a natural-born male heir upon the ruler's death.[35] It denied recognition to adopted heirs—a common practice under Hindu customary law—unless the adoption had received prior British sanction, leading to the state's direct incorporation into Company territory.[36] Dalhousie justified the policy as a corrective measure against perceived misgovernment in states devolving to minors or distant relatives via adoption, asserting it aligned with the Company's paramountcy to promote efficient administration and prevent hereditary incompetence.[37] The doctrine's application was selective, primarily to Hindu-ruled states bound by subsidiary alliances or treaties implying British oversight of succession, though it disregarded indigenous traditions where adoption preserved dynastic continuity without natural progeny.[38] Satara marked the first major annexation in 1848, following the death of its raja without issue; the state, covering approximately 7,500 square miles, was absorbed despite an attempted adoption.[35] Subsequent cases included smaller principalities like Jaitpur and Sambalpur in 1849, where rulers died heirless and adoptions were rejected, yielding territories of limited but strategically useful size.[36] Larger annexations followed, notably Jhansi in 1853 after Regent Rani Lakshmibai's adopted heir was disallowed, and Nagpur in 1854, a prosperous state of over 30,000 square miles annexed upon the raja's death without recognized successor, its revenues redirected to British coffers.[37] Awadh's 1856 annexation, though framed under misadministration rather than strict lapse, exemplified the policy's expansive logic, incorporating a kingdom of 24,000 square miles and fueling elite grievances.[35] Between 1848 and 1856, the doctrine facilitated the absorption of at least seven states, adding roughly 100,000 square miles to direct British control.[36]| State Annexed | Year | Approximate Area (sq. miles) | Key Circumstance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Satara | 1848 | 7,500 | Raja's death without natural heir; adoption rejected.[35] |

| Jaitpur | 1849 | <1,000 | Heirless ruler; prior subsidiary ties.[36] |

| Sambalpur | 1849 | 2,000 | Raja died without issue.[37] |

| Baghat | 1850 | <500 | Lack of approved successor.[35] |

| Jhansi | 1853 | 3,000 | Regent's adoption disallowed.[38] |

| Nagpur | 1854 | 30,000+ | Raja's death; major revenue loss to state.[37] |