Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Labyrinthulomycetes

View on Wikipedia

| Labyrinthulomycetes | |

|---|---|

| |

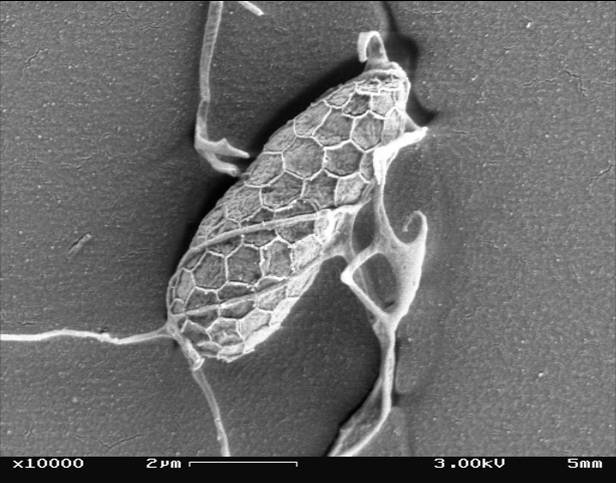

| Cell with network of ectoplasmic filaments (Aplanochytrium sp.) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Clade: | Sar |

| Clade: | Stramenopiles |

| Phylum: | Bigyra |

| Subphylum: | Sagenista |

| Class: | Labyrinthulomycetes Arx, 1970, Dick, 2001 |

| Orders[1] | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Labyrinthulomycetes (ICNafp) or Labyrinthulea[2] (ICZN) is a class of protists that produce a network of filaments or tubes,[3] which serve as tracks for the cells to glide along and absorb nutrients for them. The two main groups are the labyrinthulids (or slime nets) and thraustochytrids. They are mostly marine, commonly found as parasites on algae and seagrasses or as decomposers on dead plant material. They also include some parasites of marine invertebrates and mixotrophic species that live in a symbiotic relationship with zoochlorella.[4][5][6]

Characteristics

[edit]Although they are outside the cells, the filaments of Labyrinthulomycetes are surrounded by a membrane. They are formed and connected with the cytoplasm by a unique organelle called a sagenogen or bothrosome. The cells are uninucleated and typically ovoid, and move back and forth along the amorphous network at speeds varying from 5-150 μm per minute. Among the labyrinthulids, the cells are enclosed within the tubes, and among the thraustochytrids, they are attached to their sides.

Evolution

[edit]Evolutionary origin

[edit]Labyrinthulomycetes are not fungi, but a monophyletic group of eukaryotes within the Stramenopiles. They belong to the phylum Bigyra, which contains other heterotrophic microorganisms such as the bicosoecids. Considering that the plastids from Stramenopiles are possibly the result of an event of endosymbiosis in their last common ancestor, the bicosoecids and the labyrinthulomycetes could have originated from a mixotrophic algal common ancestor that secondarily lost their plastids.[3]

Some characteristics of the labyrinthulomycetes can be explained by their origin from ancestral plastids. They produce omega-3 poly-unsaturated fatty acids using a desaturase usually present in chloroplasts. The zoospores of labyrinthulids have an eyespot composed of membrane-bound granules that resembles eyespots of photosynthetic stramenopiles, which are either within a plastid or believed to be derived from a plastid.[3]

Within Bigyra, the labyrinthulomycetes are the sister group to Eogyrea, a class containing the species Pseudophyllomitus vesiculosus and the environmental clade called MAST-4. Together they compose the subphylum Sagenista.[7][8]

| Stramenopiles | |

Classification

[edit]Labyrinthulomycetes or Labyrinthulea used to compose the defunct fungal phylum Labyrinthulomycota.[9] They were originally considered unusual slime moulds, although they are not very similar to the other sorts. The structure of their zoospores and genetic studies show them to be a primitive group of heterokonts, but their classification and treatment remains somewhat unsettled.

This class usually contained two orders, Labyrinthulales and Thraustochytriales (ICBN), or Labyrinthulida and Thraustochytrida (ICZN), but a different classification has recently been proposed.[6][10][11][1][9]

- Order Labyrinthulales/Labyrinthulida E. A. Bessey 1950/Doffein 1901

- Family Aplanochytriaceae/Aplanochytriidae Leander ex Cavalier-Smith 2012

- Aplanochytrium Bahnweg & Sparrow 1972 [=Labyrinthuloides Perkins 1973]

- Family Labyrinthulaceae/Labyrinthulidae Haeckel 1868/Cinekowksa 1867

- Labyrinthomyxa Duboscq 1921

- Pseudoplasmodium Molisch 1925

- Labyrinthula Cienkowski 1864 [=Labyrinthodictyon Valkanov 1969; Labyrinthorhiza Chadefaud 1956]

- Family-level clade "Stellarchytriaceae/Stellarchytriidae" – this group is provisionally placed in Labyrinthulida[9][1] but, according to phylogenetic analyses, diverges before the rest of labyrinthulean clades.[11]

- Stellarchytrium FioRito & Leander 2016

- Family Aplanochytriaceae/Aplanochytriidae Leander ex Cavalier-Smith 2012

- Order Oblongichytriales/Oblongichytrida

- Family Oblongichytriaceae/Oblongichytriidae Cavalier-Smith 2012

- Oblongichytrium Yokoyama & Honda 2007

- Family Oblongichytriaceae/Oblongichytriidae Cavalier-Smith 2012

- Order Thraustochytriales/Thraustochytrida Sparrow 1973

- Pyrrhosorus Juel 1901

- Thanatostrea Franc & Arvy 1969

- Family Althornidiaceae/Althorniidae Jones & Alderman 1972

- Althornia Jones & Alderman 1972

- Family Thraustochytriacae/Thraustochytriidae Sparrow ex Cejp 1959

- Japanochytrium Kobayasi & Ôkubo 1953

- Monorhizochytrium Doi & Honda 2017

- Sicyoidochytrium Yokoy., Salleh & Honda 2007

- Aurantiochytrium Yokoy. & Honda 2007

- Ulkenia Gaertn. 1977

- Parietichytrium Yokoy., Salleh & Honda 2007

- Botryochytrium Yokoy., Salleh & Honda 2007

- Schizochytrium Goldst. & Belsky emend. Booth & Mill.

- Thraustochytrium Sparrow 1936

- Hondaea Amato & Cagnac 2018

- Labyrinthulochytrium Hassett & Gradinger 2018[12]

- Order "Amphitremidales"/Amphitremida Gomaa et al. 2013

- Family "Amphitremidiaceae"/Amphitremidae Poch 1913

- Paramphitrema Valkanov 1970

- Archerella Loeblich & Tappan 1961

- Amphitrema Archer 1867

- Family "Diplophrydaceae"/Diplophryidae Cavalier-Smith 2012

- Diplophrys Barker 1868

- Family "Amphitremidiaceae"/Amphitremidae Poch 1913

- Order "Amphifilales"/Amphifilida Cavalier Smith 2012

- Family Sorodiplophryidae Cavalier-Smith 2012

- Sorodiplophrys Olive & Dykstra 1975

- Fibrophrys Takahashi et al. 2016

- Family Amphifilidae Cavalier-Smith 2012

- Genus Amphifila Cavalier-Smith 2012

- Family Sorodiplophryidae Cavalier-Smith 2012

Genetic code

[edit]The labyrinthulomycete Thraustochytrium aureum is notable for the alternative genetic code of its mitochondria which use TTA as a stop codon instead of coding for Leucine.[13] This code is represented by NCBI translation table 23, Thraustochytrium mitochondrial code.[14]

| Genetic code | Translation table |

DNA codon | RNA codon | Translation with this code |

Standard code (Translation table 1) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thraustochytrium mitochondrial | 23 | TTA | UUA | STOP = Ter (*) | Leu (L) | |||

Gallery

[edit]-

Aplanochytrium sp. under light microscope

-

Aplanochytrium sp. under SEM

-

Aurantiochytrium sp.

-

Test of Amphitrema, a testate amoeba recently included in the group

-

Leon Cienkowski, Russian botanist who in 1867 described Labyrinthula, the first genus of the group[15]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Adl SM, Bass D, Lane CE, Lukeš J, Schoch CL, Smirnov A, Agatha S, Berney C, Brown MW, Burki F, Cárdenas P, Čepička I, Chistyakova L, del Campo J, Dunthorn M, Edvardsen B, Eglit Y, Guillou L, Hampl V, Heiss AA, Hoppenrath M, James TY, Karnkowska A, Karpov S, Kim E, Kolisko M, Kudryavtsev A, Lahr DJG, Lara E, Le Gall L, Lynn DH, Mann DG, Massana R, Mitchell EAD, Morrow C, Park JS, Pawlowski JW, Powell MJ, Richter DJ, Rueckert S, Shadwick L, Shimano S, Spiegel FW, Torruella G, Youssef N, Zlatogursky V, Zhang Q (2019). "Revisions to the Classification, Nomenclature, and Diversity of Eukaryotes". Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology. 66 (1): 4–119. doi:10.1111/jeu.12691. PMC 6492006. PMID 30257078.

- ^ Cavalier-Smith, T. (1997). "Sagenista and bigyra, two phyla of heterotrophic heterokont chromists". Archiv für Protistenkunde. 148 (3): 253–267. doi:10.1016/S0003-9365(97)80006-1.

- ^ a b c Tsui, Clement K M; Marshall, Wyth; Yokoyama, Rinka; Honda, Daiske; Lippmeier, J Casey; Craven, Kelly D; Peterson, Paul D; Berbee, Mary L (January 2009). "Labyrinthulomycetes phylogeny and its implications for the evolutionary loss of chloroplasts and gain of ectoplasmic gliding". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 50 (1): 129–40. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2008.09.027. PMID 18977305.

- ^ Schärer, L.; Knoflach, D.; Vizoso, D. B.; Rieger, G.; Peintner, U. (2007). "Thraustochytrids as novel parasitic protists of marine free-living flatworms: Thraustochytrium caudivorum sp. nov. Parasitizes Macrostomum lignano" (PDF). Marine Biology. 152 (5): 1095. doi:10.1007/s00227-007-0755-4. S2CID 4836350.

- ^ Pan, Jingwen (2016). Labyrinthulomycetes diversity meta-analysis (MSc). University of British Columbia. doi:10.14288/1.0223199.

- ^ a b Gomaa, Fatma; Mitchell, Edward A. D.; Lara, Enrique (2013). "Amphitremida (poche, 1913) is a new major, ubiquitous labyrinthulomycete clade". PLoS One. 8 (1) e53046. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...853046G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0053046. PMC 3544814. PMID 23341921.

- ^ Cavalier-Smith, Thomas (2017). "Kingdom Chromista and its eight phyla: a new synthesis emphasising periplastid protein targeting, cytoskeletal and periplastid evolution, and ancient divergences". Protoplasma. 255 (1): 297–357. doi:10.1007/s00709-017-1147-3. PMC 5756292. PMID 28875267.

- ^ Thakur, Rabindra; Shiratori, Takashi; Ishida, Ken-ichiro (2019). "Taxon-rich Multigene Phylogenetic Analyses Resolve the Phylogenetic Relationship Among Deep-branching Stramenopiles". Protist. 170 (5) 125682. doi:10.1016/j.protis.2019.125682. ISSN 1434-4610. PMID 31568885. S2CID 202865459.

- ^ a b c Bennett, Reuel M.; Honda, D.; Beakes, Gordon W.; Thines, Marco (2017). "Chapter 14. Labyrinthulomycota". In Archibald, John M.; Simpson, Alastair G.B.; Slamovits, Claudio H. (eds.). Handbook of the Protists. Springer. pp. 507–542. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-28149-0_25. ISBN 978-3-319-28147-6.

- ^ Anderson, O. Roger; Cavalier-Smith, Thomas (2012). "Ultrastructure of Diplophrys parva, a New Small Freshwater Species, and a Revised Analysis of Labyrinthulea (Heterokonta)". Acta Protozoologica. 8 (1): 291–304. doi:10.4467/16890027AP.12.023.0783.

- ^ a b FioRito, Rebecca; Leander, Celeste; Leander, Brian (2016). "Characterization of three novel species of Labyrinthulomycota isolated from ochre sea stars (Pisaster ochraceus)". Marine Biology. 163 (8): 170. doi:10.1007/s00227-016-2944-5. S2CID 43399688.

- ^ Hassett, Brandon T.; Gradinger, Rolf (2018). "New Species of Saprobic Labyrinthulea (=Labyrinthulomycota) and the Erection of a gen. nov. to Resolve Molecular Polyphyly within the Aplanochytrids". Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology. 65 (4): 475–483. doi:10.1111/jeu.12494. hdl:10037/13570. ISSN 1550-7408. PMID 29265676. S2CID 46820836.

- ^ Wideman, Jeremy G.; Monier, Adam; Rodríguez-Martínez, Raquel; Leonard, Guy; Cook, Emily; Poirier, Camille; Maguire, Finlay; Milner, David S.; Irwin, Nicholas A. T.; Moore, Karen; Santoro, Alyson E. (2019-11-25). "Unexpected mitochondrial genome diversity revealed by targeted single-cell genomics of heterotrophic flagellated protists". Nature Microbiology. 5 (1): 154–165. doi:10.1038/s41564-019-0605-4. hdl:10871/39819. ISSN 2058-5276. PMID 31768028. S2CID 208279678.

- ^ Elzanowski A, Ostell J, Leipe D, Soussov V. "The Genetic Codes". Taxonomy browser. National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), U.S. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 11 August 2016.

- ^ Cienkowski, L. (1867). Ueber den Bau und die Entwicklung der Labyrinthuleen. Arch. mikr. Anat., 3:274, [1].

External links

[edit]Labyrinthulomycetes

View on GrokipediaTaxonomy and Classification

Higher Taxonomy

Labyrinthulomycetes belongs to the domain Eukaryota, within the supergroup SAR (Stramenopiles, Alveolates, and Rhizaria), phylum Stramenopiles (also known as Heterokonts), subphylum Sagenista, and class Labyrinthulomycetes.[4] The class was originally established by J.A. von Arx in 1970 as part of a classification of fungi sporulating in pure culture, reflecting early perceptions of these organisms as fungus-like. It was subsequently emended by M.W. Dick in 2001 to incorporate their protistan nature and align with straminipilous systematics, emphasizing shared features with other heterotrophic stramenopiles. Historically, Labyrinthulomycetes were misclassified as slime molds within Myxomycota due to their colonial growth, ectoplasmic networks, and saprotrophic habits, which superficially resembled fungal or myxomycete structures. This placement persisted into the mid-20th century until ultrastructural studies in the 1970s and 1980s revealed diagnostic heterokont features, such as tubular cristae in mitochondria, Golgi-derived scales on cell walls, and biflagellate zoospores with heterokont flagellation (one anterior tinsel flagellum and one posterior smooth flagellum). Molecular evidence from 18S rRNA gene phylogenies beginning in the late 1980s and early 1990s further confirmed their position among stramenopiles, distinguishing them from true fungi and myxomycetes by signatures like specific base pairings in ribosomal helices. In the current taxonomy outlined by Adl et al. (2019), Labyrinthulomycetes is recognized as a monophyletic class within the phylum Bigyra of Stramenopiles, forming a sister group to the class Eogyrea, which includes environmental clades and species like Pseudophyllomitus vesiculosus.[4] This placement is supported by phylogenomic analyses integrating 18S rRNA and multigene data, resolving Bigyra as a basal heterotrophic lineage in Stramenopiles. Key diagnostic traits reinforcing this higher placement include their heterotrophic nutrition, production of biflagellate zoospores, and unique ectoplasmic elements (such as bothrosomes or sagenogens) for motility and nutrient uptake, which are characteristic of stramenopile osmotrophs.[4][5]Orders and Families

The internal classification of Labyrinthulomycetes recognizes five orders: Amphitremida, Amphifilida, Oblongichytriida, Labyrinthulida, and Thraustochytrida.[4] These orders encompass diverse morphologies and life cycles, with Thraustochytrida including decomposer genera like Thraustochytrium and Schizochytrium, and Labyrinthulida featuring slime-net producers like Labyrinthula. Amphitremida includes phagotrophic forms such as Amphitrema, while Amphifilida and Oblongichytriida represent less-studied groups with amoeboid and zoospore-based forms, respectively. Nomenclature within Labyrinthulomycetes remains unsettled due to their ambiguous status as fungus-like protists, leading to dual regulatory systems: the International Code of Botanical Nomenclature (ICBN) for fungal affinities and the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN) for protistan traits.[6] Approximately 50–60 species of Labyrinthulomycetes have been formally described, though environmental sequencing indicates substantial undescribed diversity, including over 200 operational taxonomic units recovered from marine sediments.[6] Key genera illustrate this diversity: Labyrinthula, which produces ectoplasmic slime nets often associated with algal substrates; Thraustochytrium, a decomposer commonly found on organic detritus; and Diplophrys, a representative in freshwater environments.[6][4]| Order | Family | Representative Genera |

|---|---|---|

| Amphitremida | Amphitremidae | Amphitrema, Archerella |

| Amphifilida | Diplophryidae | Diplophrys, Quondamattia |

| Oblongichytriida | Oblongichytriaceae | Oblongichytrium |

| Labyrinthulida | Labyrinthulaceae | Labyrinthula, Aplanochytrium |

| Thraustochytrida | Thraustochytriaceae | Thraustochytrium, Schizochytrium, Aurantiochytrium |

| Thraustochytrida | Aplanochytriaceae | Aplanochytrium |

![Leon Cienkowski, Russian botanist who in 1867 described Labyrinthula, the first genus of the group[15]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/dc/Tsenkovsky_Lev_Semyonovich.jpg/120px-Tsenkovsky_Lev_Semyonovich.jpg)