Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Social game

View on WikipediaA social game may refer to tabletop games, other face-to-face indoor or outdoor games, or video games that allow or require social interaction between players as opposed to games played in solitude, games played at tournaments or competitions or games played for money.[1]

Definition and origins

[edit]This section needs expansion with: social outdoor games and modern social video games as introduced by opening blurb. You can help by adding to it. (October 2025) |

The majority of social games are board games or card games. As a rule, this also includes word games (like Scrabble), guessing games or charades. Board games range from pure games of chance (e.g. many dice games) to games of thought or skill (chess and Go,[verification needed] role-playing games or tag and hide and seek) to various party games such as spin the bottle and - with a centuries-long tradition - blind man's buff.

Some authors use a narrower definition of social games, for example only including games "played with the aid of a board, game pieces and other material on the table,"[2] so that, for example, pure card games are excluded. In this case, the terms "social game" and "board game" are largely synonymous. The Libro de los Juegos ("Book of Games") written in 1283 on behalf of the Castilian king Alfonso the Wise, already distinguishes social games from sports. There, board and dice games are characterized by the fact that they are played while sitting, unlike sports that are played on foot or on horseback.[3]

The name parlour game goes back to the term parlour for an indoor reception room in well-to-do and aristocratic houses. The phrase was later extended to an entertaining game "played by several children or adults together."[4]

Historical development

[edit]This section needs expansion with: social outdoor games and modern social video games as introduced by opening blurb. You can help by adding to it. (October 2025) |

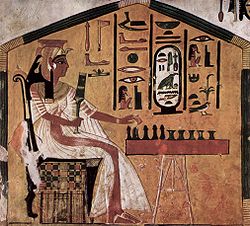

Board games

[edit]The oldest evidence of board games are pictorial representations of players as well as excavated game boards from Ancient Egypt – there mostly as grave goods – and from Babylonia. However, it is generally not doubted that such games had been played earlier, for example on playing fields that were drawn in the sand, as is still common today in mancala games in Africa (pictured). A board for the Royal Game of Ur unearthed in the royal cemetery of the Sumerian city of Ur dates to 2600 to 2400 BC.[5] In 2006, a 3,500-year-old Senet game made of wood and ivory was discovered.[6] The game is therefore a little older than the Senet games found in the tomb of Tutankhamun.

The oldest board games still in use today are Go and nine men's morris, both of which were certainly played before 0 AD.[7][8] Chess and games of the Mancala family have a tradition that is over a thousand years old.

Dice games have a history of over 4,000 years thanks to surviving dice that have been found.[9]

Card games are much younger and can be traced back to traditional bans in Europe from the 14th century. However, historians tend to assume that the tradition of playing cards has its origins in China and India, where paper production existed much earlier as the basis for card production.[10]

-

Board game without a board: children in Nigeria play Mancala variant Ayo

-

Royal game of Ur (2600–2400 BC) in the British Museum

-

Game of Amenhotep III (?–c. 1350 BC)

-

Spanish playing cards from the 15th century

One of the first games that was commercially produced and sold in the 19th century with a printed graphic as a game board was the game of the Goose, which can be traced back to the 16th century.[11]

Early examples of commercial board games in Europe, some with the well-known names of their authors, are Snakes and ladders, sold in England from 1892 and marketed in Europe from 1893 by Ravensburger, Reversi, Salta, which was sold from 1899, Mensch ärgere dich nicht, created in 1910 based on the Indian game of Pachisi, Laska invented in 1911 by world chess champion Emanuel Lasker and the game of Coppit), designed in 1927 in the modern Bauhaus stype.[12]

In the US, commercial board games were marketed from the second half of the 19th century by publishers such as Parker and Milton Bradley (MB).[13][14] The classic game of Monopoly, which was based on a model of The Landlord's Game patented in 1904, was produced in large numbers from 1935 onwards. A significant impulse came from games published from around 1960, including Risk (Risk, 1959), The Game of Life and as part of the 3M Game Edition games like Acquire and TwixT.[15] The authors of the last two games mentioned, Sid Sackson and Alex Randolph, respectively, had a significant influence on the further development of board games in the following decades, especially in Germany, with titles like Sleuth, Focus, Can't Stop and Metropolis or Enchanted Forest, What the Heck?, Inkognito and Good & Bad Ghosts.

-

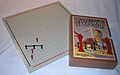

Mensch ärgere Dich nicht, 1929 edition

-

Coppit

-

Risk

-

3M edition of Twixt

Card games

[edit]Playing cards are thought by scholars to have been invented in China before AD 1000 and were introduced into Europe in the late 14th century from Egypt.[16] However, nothing is known of the games played with them at that time. The earliest known game in Europe with a continuous record of play down to the present day is Karnöffel which was well known enough in Nördlingen, Bavaria, in 1426 to be excluded from a list of banned gambling games. Karnöffel became very popular with soldiers and peasants, probably because of the scurrilous ranking of its cards in which Kings and Queens became worthless, cards called the Popes (6s) were demoted, a peasant (the Karnöffel) was promoted to the top card and cards called Devils (7s) could become all powerful when led to a trick. The game was sufficient well known in the early 16th century that, in 1537, Martin Luther wrote a satirical letter to the Pope from the "Holy Order of Karnöffel Card Players". The game is still played today in various forms, especially in Switzerland, in German North Frisia, in Greenland and the Faroe Islands of Denmark.

Karnöffel had a chosen suit, but no trumps – they were invented around 1420 when the Duke of Milan ordered a special pack of cards to be made containing an extra suit – these were the first Tarot cards.[17]

However, no rules for his game are known; the earliest recorded rules for any Tarot game are those by Michel de Marolles written down in 1637 for Princess Louise-Marie de Gonzague-Nevers, later Queen of Poland. The concept of trumps, or triumphs as they were first known, was copied from Tarot games into those played with an ordinary pack, the first being the eponymous game of Triomphe whose rules are first described by Juan Luis Vives in his Exercitatio linguae latinae around 1538 in Basel, although the game was well known by then and had probably imported it from Spain.[18] Certainly by 1529 the game of Triumph is recorded by Hugh Latimer in England. The popularity and rapid expansion of different card games is evidenced by early authors, including Rabelais,[19] who produces a long list in which many of the games are recognisable from their names, but many others are also unclear.

After trumps, the next major feature to be introduced into card games was the concept of bidding which first appeared in the Spanish game of Tresillo, known everywhere else as Ombre or l'Hombre, said by Sir Michael Dummett to be the most successful card game ever invented.[20] Ombre spread rapidly across Europe generating a host of other games including Quadrille which was played in England. Its influence is still seen in card games today, including contract bridge, skat, oh hell, English solo, préférence, bid whist, tarot card games like cego and Königrufen and many others.

Types

[edit]Types of social games can include:

- Tabletop games

- Card games, that involve multiple players i.e. excluding patiences or solitaires

- Board games, in which counters or pieces are placed, removed, or moved on a premarked surface according to a set of rules

- Miniature wargaming, a form of wargaming that incorporates miniature figures, miniature armor and modeled terrain

- Tabletop role-playing games, a game in which players assume the roles of characters in a fictional setting

- Other face-to-face social games

- Game of chance, a game whose outcome is strongly influenced by some randomizing device

- Game of dares (or a dare game) is a game in which people dare each other to perform actions that they would not normally do.

- Parlour games, indoor games such as charades

- Lawn games, outdoor games such as those played on field day

- Street games, outdoor games played on the streets rather than on a field

- Live action role-playing games, a form of role-playing game where the participants physically act out their characters' actions

- Alternate reality games, an interactive narrative using the real world as a platform

- Video games

- Mobile games, which can include social network games, which played on mobile devices

- Social network games, games that have social network integration or elements

- Multiplayer video games, where more than one person can play in the same game environment at the same time

- LAN parties, a temporary gathering of people establishing a local area network (LAN), primarily for the purpose of playing multiplayer computer games

- Massively multiplayer online games, video games where a large number of players can exist on the same server simultaneously

- Online gambling (or Internet gambling) is any kind of gambling conducted on the internet.

References

[edit]- ^ Aichner, T.; Jacob, F. (March 2015). "Measuring the Degree of Corporate Social Media Use". International Journal of Market Research. 57 (2): 257–275. doi:10.2501/IJMR-2015-018. S2CID 166531788.

- ^ Erwin Glonnegger: Das Spiele-Buch, Drei Zauberer Verlag, expanded new edition 1999, ISBN 3-9806792-0-9, p. 6.

- ^ Libro de los Juegos. Alfons X "the Wise", translated and commentated on by Ulrich Schädler and Ricardo Calvo, Lit Verlag, Vienna 2009, ISBN 978-3-643-50011-3.Social game, p. 53, at Google Books.

- ^ Duden (spelling), keyword Gesellschaftsspiel , accessed 20 May 2018

- ^ Trustees of the British Museum. "The Royal Game of Ur". The British Museum. Retrieved 2019-07-28.

- ^ "Brettspiel im Grab". Der Spiegel (16): 133. 2006-04-15. 46637208.

- ^ Michael Koulen: Go. Die Mitte des Himmels, Cologne 1986, pp. 10 ff.

- ^ Hans Schürmann, Manfred Nüscheler: So gewinnt man Mühle. Otto Maier, Ravensburg 1980, p. 4.

- ^ Ulrich Vogt: Der Würfel ist gefallen. 5000 Jahre rund um den Kubus; Hildesheim 2012, p. 17

- ^ Hugo Kastner, Gerald Kador Folkvord: Die große Humboldt-Enzyklopädie der Kartenspiele, Baden-Baden 2005, p. 14.

- ^ Manfred Zollinger: Zwei unbekannte Regeln des Gänsespiels, in: Board Games Studies, Volume 6 (2003), pp. 61–84 (online)

- ^ Erwin Glonnegger: Das Spiele-Buch. Brett- und Legespiele aus aller Welt, Herkunft, Regeln und Geschichte, Drei Zauberer Verlag, Uehlfeld 1999, ISBN 3-9806792-0-9.

- ^ Bruce Whitehill, Games of America in the Nineteenth Century, Board Game Studies Journal, Volume 9, 2015, pp. 65–87 (online)

- ^ Bruce Whitehill: American Games: A Historical Perspective, in: Board Games Studies, Volume 2, 1999, pp. 116–142 (=114 online)

- ^ Stewart Woods: Eurogames. The Design, Culture and Play of Modern European Board Games, Jefferson, N. C. 2012, ISBN 978-0-7864-6797-6, Social game, p. 32, at Google Books

- ^ Who invented playing cards and what is the origin of 'Hearts', 'Diamonds', 'Clubs' and 'Spades'? at theguardian.com. Retrieved 25 November 2023.

- ^ Pratesi, Franco (1989). "Italian Cards - New Discoveries". The Playing-Card. 18 (1, 2): 28–32, 33–38.

- ^ Vives, Juan Luis; Foster, Watson (1908). Tudor School-Boy Life. London: J.M. Dent & Company. pp. 185–197.

- ^ Rabelais, François (1534), Gargantua and Pantagruel, Book 1, Chapter 22.

- ^ Dummett (1980), p. 173.