Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Solar inverter

View on Wikipedia

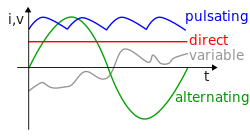

A solar inverter or photovoltaic (PV) inverter is a type of power inverter which converts the variable direct current (DC) output of a photovoltaic solar panel into a utility frequency alternating current (AC) that can be fed into a commercial electrical grid or used by a local, off-grid electrical network. It is a critical balance of system (BOS)–component in a photovoltaic system, allowing the use of ordinary AC-powered equipment. Solar power inverters have special functions adapted for use with photovoltaic arrays, including maximum power point tracking and anti-islanding protection.

Classification

[edit]

Solar inverters may be classified into four broad types:[2]

- Stand-alone inverters, used in stand-alone power systems where the inverter draws its DC energy from batteries charged by photovoltaic arrays. Many stand-alone inverters also incorporate integral battery chargers to replenish the battery from an AC source when available. Normally these do not interface in any way with the utility grid, and as such are not required to have anti-islanding protection.

- Grid-tie inverters, which match phase with a utility-supplied sine wave. Grid-tie inverters are designed to shut down automatically upon loss of utility supply, for safety reasons. They do not provide backup power during utility outages.

- Off-grid inverters, also known as stand-alone inverters, are designed for use in power systems that operate independently of the utility grid. These inverters convert direct current (DC) electricity from solar panels or batteries into alternating current (AC) for use in homes, cabins, or remote areas without access to grid power. They typically rely on battery storage systems, which are charged by photovoltaic arrays, and are capable of powering AC loads directly. Off-grid inverters do not require anti-islanding protection, as they are not connected to the grid.[3]

- Battery backup inverters are special inverters which are designed to draw energy from a battery, manage the battery charge via an onboard charger, and export excess energy to the utility grid. These inverters are capable of supplying AC energy to selected loads during a utility outage, and are required to have anti-islanding protection.[clarification needed]

- Intelligent hybrid inverters manage photovoltaic array, battery storage and utility grid, which are all coupled directly to the unit. These modern all-in-one systems are usually highly versatile and can be used for grid-tie, stand-alone or backup applications but their primary function is self-consumption with the use of storage.

Maximum power point tracking

[edit]Solar inverters use maximum power point tracking (MPPT) to get the maximum possible power from the PV array.[4] Solar cells have a complex relationship between solar irradiation, temperature and total resistance that produces a non-linear output efficiency known as the I-V curve. It is the purpose of the MPPT system to sample the output of the cells and determine a resistance (load) to obtain maximum power for any given environmental conditions.[5]

The fill factor, more commonly known by its abbreviation FF, is a parameter which, in conjunction with the open circuit voltage (Voc) and short circuit current (Isc) of the panel, determines the maximum power from a solar cell. Fill factor is defined as the ratio of the maximum power from the solar cell to the product of Voc and Isc.[6]

There are three main types of MPPT algorithms: perturb-and-observe, incremental conductance and constant voltage.[7] The first two methods are often referred to as hill climbing methods; they rely on the curve of power plotted against voltage rising to the left of the maximum power point, and falling on the right.[8]

Grid tied solar inverters

[edit]

The key role of the grid-interactive or synchronous inverters or simply the grid-tie inverter (GTI) is to synchronize the phase, voltage, and frequency of the power line with that of the grid.[9] Solar grid-tie inverters are designed to quickly disconnect from the grid if the utility grid goes down. In the United States, for example, this is an NEC requirement that ensures that in the event of a blackout, the grid tie inverter will shut down to prevent the energy it produces from harming any line workers who are sent to fix the power grid.

Grid-tie inverters that are available on the market today[when?] use a number of different technologies. The inverters may use the newer high-frequency transformers, conventional low-frequency transformers, or no transformer. Instead of converting direct current directly to 120 or 240 volts AC, high-frequency transformers employ a computerized multi-step process that involves converting the power to high-frequency AC and then back to DC and then to the final AC output voltage.[10]

Historically, there have been concerns about having transformerless electrical systems feed into the public utility grid. The concerns stem from the fact that there is a lack of galvanic isolation between the DC and AC circuits, which could allow the passage of dangerous DC faults to the AC side.[11] Since 2005, the NFPA's NEC allows transformer-less (or non-galvanically isolated) inverters. The VDE 0126-1-1 and IEC 6210 also have been amended to allow and define the safety mechanisms needed for such systems. Primarily, residual or ground current detection is used to detect possible fault conditions. Also isolation tests are performed to ensure DC to AC separation.

Many solar inverters are designed to be connected to a utility grid, and will not operate when they do not detect the presence of the grid. They contain special circuitry to precisely match the voltage, frequency and phase of the grid. When a grid is not detected, grid-tie inverters will not produce power to avoid islanding which can cause safety issues.

Solar pumping inverters

[edit]Advanced solar pumping inverters convert DC voltage from the solar array into AC voltage to drive submersible pumps directly without the need for batteries or other energy storage devices. By utilizing MPPT (maximum power point tracking), solar pumping inverters regulate output frequency to control the speed of the pumps in order to save the pump motor from damage.[citation needed]

Solar pumping inverters usually have multiple ports to allow the input of DC current generated by PV arrays, one port to allow the output of AC voltage, and a further port for input from a water-level sensor.

Three-phase-inverter

[edit]A three-phase-inverter is a type of solar microinverter specifically design to supply three-phase electric power. In conventional microinverter designs that work with one-phase power, the energy from the panel must be stored during the period where the voltage is passing through zero, which it does twice per cycle (at 50 or 60 Hz). In a three phase system, throughout the cycle, one of the three wires has a positive (or negative) voltage, so the need for storage can be greatly reduced by transferring the output of the panel to different wires during each cycle. The reduction in energy storage significantly lowers the price and complexity of the converter hardware, as well as potentially increasing its expected lifetime.

Concept

[edit]Background

[edit]Conventional alternating current power is a sinusoidal voltage pattern that repeats over a defined period. That means that during a single cycle, the voltage passes through zero two times. In European systems the voltage at the plug has a maximum of 230 V and cycles 50 times a second, meaning that there are 100 times a second where the voltage is zero, while North American derived systems are 120 V 60 Hz, or 120 zero voltages a second.

Inexpensive inverters can convert DC power to AC by simply turning the DC side of the power on and off 120 times a second, inverting the voltage every other cycle. The result is a square-wave that is close enough to AC power for many devices. However, this sort of solution is not useful in the solar power case, where the goal is to convert as much of the power from the solar power into AC as possible. If one uses these inexpensive types of inverters, all of the power generated during the time that the DC side is turned off is simply lost, and this represents a significant amount of each cycle.

To address this, solar inverters use some form of energy storage to buffer the panel's power during those zero-crossing periods. When the voltage of the AC goes above the voltage in the storage, it is dumped into the output along with any energy being developed by the panel at that instant. In this way, the energy produced by the panel through the entire cycle is eventually sent into the output.

The problem with this approach is that the amount of energy storage needed when connected to a typical modern solar panel can only economically be provided through the use of electrolytic capacitors. These are relatively inexpensive but have well-known degradation modes that mean they have lifetime expectancy on the order of a decade. This has led to a great debate in the industry over whether or not microinverters are a good idea, because when these capacitors start to fail at the end of their expected life, replacing them will require the panels to be removed, often on the roof.

Three-phase

[edit]

In comparison to normal household current on two wires, current on the delivery side of the power grid uses three wires and phases. At any given instant, the sum of those three is always positive (or negative). So while any given wire in a three-phase system undergoes zero-crossing events in exactly the same fashion as household current, the system as a whole does not, it simply fluctuates between the maximum and a slightly lower value.

A microinverter designed specifically for three-phase supply can eliminate much of the required storage by simply selecting which wire is closest to its own operating voltage at any given instant. A simple system could simply select the wire that is closest to the maximum voltage, switching to the next line when that begins to approach the maximum. In this case, the system only has to store the amount of energy from the peak to the minimum of the cycle as a whole, which is much smaller both in voltage difference and time.

This can be improved further by selecting the wire that is closest to its own DC voltage at any given instant, instead of switching from one to the other purely on a timer. At any given instant two of the three wires will have a positive (or negative) voltage and using the one closer to the DC side will take advantage of slight efficiency improvements in the conversion hardware.

The reduction, or outright elimination, of energy storage requirements, simplifies the device and eliminates the one component that is expected to define its lifetime. Instead of a decade, a three-phase microinverter could be built to last for the lifetime of the panel. Such a device would also be less expensive and less complex, although at the cost of requiring each inverter to connect to all three lines, which possibly leads to more wiring.

Disadvantages

[edit]The primary disadvantage of the three-phase inverter concept is that only sites with three-phase power can take advantage of these systems. Three-phase is easily available at utility-scale and commercial sites, and it was to these markets that the systems were aimed. However, the main advantages of the microinverter concept involve issues of shading and panel orientation, and in the case of large systems, these are easily addressed by simply moving the panels around. The benefits of the three-phase micro are very limited compared to the residential case with limited space to work in.

As of 2014, observers believed that three-phase micros had not yet managed to reach the price point where their advantages appeared worthwhile. Moreover, the wiring costs for three-phase microinverters is expected to be higher.

Combining phases

[edit]It is important to contrast a native three-phase inverter with three single-phase micro-inverters wired to output in three-phase. The latter is a relatively common feature of most inverter designs, allowing you to connect three identical inverters together, each across a pair of wires in a three-phase circuit. The result is three-phase power, but each inverter in the system is outputting a single phase. These sorts of solutions do not take advantage of the reduced energy storage needs outlined above.

Solar micro-inverters

[edit]

Solar micro-inverter is an inverter designed to operate with a single PV module. The micro-inverter converts the direct current output from each panel into alternating current. Its design allows parallel connection of multiple, independent units in a modular way.[12]

Micro-inverter advantages include single panel power optimization, independent operation of each panel, plug-and play installation, improved installation and fire safety, minimized costs with system design and stock minimization.

A 2011 study at Appalachian State University reports that individual integrated inverter setup yielded about 20% more power in unshaded conditions and 27% more power in shaded conditions compared to string connected setup using one inverter. Both setups used identical solar panels.[13]

A solar micro-inverter, or simply microinverter, is a plug-and-play device used in photovoltaics that converts direct current (DC) generated by a single solar module to alternating current (AC). Microinverters contrast with conventional string and central solar inverters, in which a single inverter is connected to multiple solar panels. The output from several microinverters can be combined and often fed to the electrical grid.

Microinverters have several advantages over conventional inverters. The main advantage is that they electrically isolate the panels from one another, so small amounts of shading, debris or snow lines on any one solar module, or even a complete module failure, do not disproportionately reduce the output of the entire array. Each microinverter harvests optimum power by performing maximum power point tracking (MPPT) for its connected module.[14] Simplicity in system design, lower amperage wires, simplified stock management, and added safety are other factors introduced with the microinverter solution.

The primary disadvantages of a microinverter include a higher initial equipment cost per peak watt than the equivalent power of a central inverter since each inverter needs to be installed adjacent to a panel (usually on a roof). This also makes them harder to maintain and more costly to remove and replace. Some manufacturers have addressed these issues with panels with built-in microinverters.[15] A microinverter has often a longer lifespan than a central inverter, which will need replacement during the lifespan of the solar panels. Therefore, the financial disadvantage at first may become an advantage in the long term.

A power optimizer is a type of technology similar to a microinverter. A power optimizer uses a panel-level maximum power point tracking, but does not convert to AC per module.

Description

[edit]String inverter

[edit]Solar panels produce direct current at a voltage that depends on module design and lighting conditions. Modern modules using 6-inch cells typically contain 60 cells and produce a nominal 24-30 V.[16] (so inverters are ready for 24-50 V).

For conversion into AC, panels may be connected in series to produce an array that is effectively a single large panel with a nominal rating of 300 to 600 VDC.[a][needs update] The power then runs to an inverter, which converts it into standard AC voltage, typically 230 VAC / 50 Hz or 240 VAC / 60 Hz.[17]

The main problem with the string inverter approach is the string of panels acts as if it were a single larger panel with a max current rating equivalent to the poorest performer in the string. For example, if one panel in a string has 5% higher resistance due to a minor manufacturing defect, the entire string suffers a 5% performance loss. This situation is dynamic. If a panel is shaded its output drops dramatically, affecting the output of the string, even if the other panels are not shaded. Even slight changes in orientation can cause output loss in this fashion. In the industry, this is known as the "Christmas-lights effect", referring to the way an entire string of series-strung Christmas tree lights will fail if a single bulb fails.[18] However, this effect is not entirely accurate and ignores the complex interaction between modern string inverter maximum power point tracking and even module bypass diodes. Shade studies by major microinverter and DC optimizer companies show small yearly gains in light, medium and heavy shaded conditions – 2%, 5% and 8% respectively – over an older string inverter[19]

Additionally, the efficiency of a panel's output is strongly affected by the load the inverter places on it. To maximize production, inverters use a technique called maximum power point tracking to ensure optimal energy harvest by adjusting the applied load. However, the same issues that cause output to vary from panel to panel, affect the proper load that the MPPT system should apply. If a single panel operates at a different point, a string inverter can only see the overall change, and moves the MPPT point to match. This results in not just losses from the shadowed panel, but the other panels too. Shading of as little as 9% of the surface of an array can, in some circumstances, reduce system-wide power as much as 54%.[20][21] However, as stated above, these yearly yield losses are relatively small and newer technologies allow some string inverters to significantly reduce the effects of partial shading.[22]

Another issue, though minor, is that string inverters are available in a limited selection of power ratings. This means that a given array normally up-sizes the inverter to the next-largest model over the rating of the panel array. For instance, a 10-panel array of 2300 W might have to use a 2500 or even 3000 W inverter, paying for conversion capability it cannot use. This same issue makes it difficult to change array size over time, adding power when funds are available (modularity). If the customer originally purchased a 2500 W inverter for their 2300 W of panels, they cannot add even a single panel without over-driving the inverter. However, this over sizing is considered common practice in today's industry (sometimes as high as 20% over inverter nameplate rating) to account for module degradation, higher performance during winter months or to achieve higher sell back to the utility.

Other challenges associated with centralized inverters include the space required to locate the device, as well as heat dissipation requirements. Large central inverters are typically actively cooled. Cooling fans make noise, so location of the inverter relative to offices and occupied areas must be considered. And because cooling fans have moving parts, dirt, dust, and moisture can negatively affect their performance over time. String inverters are quieter but might produce a humming noise in late afternoon when inverter power is low.

Microinverter

[edit]Microinverters are small inverters rated to handle the output of a single panel or a pair of panels. Grid-tie panels are normally rated between 225 and 275 W, but rarely produce this in practice, so microinverters are typically rated between 190 and 220 W (sometimes, 100 W).[needs update] Because it is operated at this lower power point, many design issues inherent to larger designs simply go away; the need for a large transformer is generally eliminated, large electrolytic capacitors can be replaced by more reliable thin-film ones, and cooling loads are reduced so no fans are needed. Mean time between failures (MTBF) are quoted in hundreds of years.[23]

A microinverter attached to a single panel allows it to isolate and tune the output of that panel. Any panel that is under-performing has no effect on panels around it. In that case, the array as a whole produces as much as 5% more power than it would with a string inverter. When shadowing is factored in, if present, these gains can become considerable, with manufacturers generally claiming 5% better output at a minimum, and up to 25% better in some cases.[23] Furthermore, a single model can be used with a wide variety of panels, new panels can be added to an array at any time, and do not have to have the same rating as existing panels.

Microinverters produce grid-matching AC power directly at the back of each solar panel. The AC output of arrays of microinverter-equipped panels are connected in parallel to each other, and then to the grid. This has the major advantage that a single failing panel or inverter cannot take the entire string offline. Combined with the lower power and heat loads, and improved MTBF, some suggest that overall array reliability of a microinverter-based system is significantly greater than a string inverter-based one. [citation needed] This assertion is supported by longer warranties, typically 15 to 25 years, compared with 5 or 10-year warranties that are more typical for string inverters. Additionally, when faults occur, they are identifiable to a single point, as opposed to an entire string. This not only makes fault isolation easier, but unmasks minor problems that might not otherwise become visible – a single under-performing panel may not affect a long string's output enough to be noticed.

Disadvantages

[edit]The main disadvantage of the microinverter concept has, until recently, been cost. Because each microinverter has to duplicate much of the complexity of a string inverter but spread that out over a smaller power rating, costs on a per-watt basis are greater. This offsets any advantage in terms of simplification of individual components. As of February 2018, a central inverter costs approximately $0.13 per watt, whereas a microinverter costs approximately $0.34 per watt.[24] Like string inverters, economic considerations force manufacturers to limit the number of models they produce. Most produce a single model that may be over or undersize when matched with a specific panel.

In many cases the packaging can have a significant effect on price. With a central inverter you may have only one set of panel connections for dozens of panels, a single AC output, and one box. Microinverter installations larger than about 15 panels may require a roof mounted "combiner" breaker box as well. This can add to the overall price-per-watt.

To further reduce costs, some models control two or three panels from an inverter, reducing the packaging and associated costs. Some systems place two entire micros in a single box, while others duplicate only the MPPT section of the system and use a single DC-to-AC stage for further cost reductions. Some have suggested that this approach will make microinverters comparable in cost with those using string inverters.[25] With steadily decreasing prices, the introduction of dual microinverters and the advent of wider[26] model selections to match PV module output more closely, cost is less of an obstacle.

Microinverters have become common where array sizes are small and maximizing performance from every panel is a concern. In these cases, the differential in price-per-watt is minimized due to the small number of panels, and has little effect on overall system cost. The improvement in energy harvest given a fixed size array can offset this difference in cost. For this reason, microinverters have been most successful in the residential market, where limited space for panels constrains array size, and shading from nearby trees or other objects is often an issue. Microinverter manufacturers list many installations, some as small as a single panel and the majority under 50.[27]

An often overlooked disadvantage of micro inverters is the future operation and maintenance costs associated with them. While the technology has improved over the years the fact remains that the devices will eventually either fail or wear out[citation needed]. The installer must balance these replacement costs (around $400 per truck roll), increased safety risks to personnel, equipment and module racking against the profit margins for the installation. For homeowners, the eventual wear out or premature device failures will introduce potential damage to the roof tiles or shingles, property damage and other nuisances.

Advantages

[edit]While microinverters generally have a lower efficiency than string inverters, the overall efficiency is increased due to the fact that every inverter / panel unit acts independently. In a string configuration, when a panel on a string is shaded, the output of the entire string of panels is reduced to the output of the lowest producing panel.[citation needed] This is not the case with micro inverters.

A further advantage is found in the panel output quality. The rated output of any two panels in the same production run can vary by as much as 10% or more. This is mitigated with a microinverter configuration but not so in a string configuration. The result is maximum power harvesting from a microinverter array.

Systems with microinverters also can be changed easier, when power demands grow, or decrease over time. As every solarpanel and microinverter is a small system of its own, it acts to a certain extent independently. This means that adding one or more panels will just provide more energy, as long as the fused electricity group in a house or building is not exceeding its limits. In contrarast, with string based inverters, the inverter size need to be in accordance with the amount of panels or the amount of peak power. Choosing an oversized string-inverter is possible, when future extension is foreseen, but such a provision for an uncertain future increases the costs in any case.

Monitoring and maintenance is also easier as many microinverter producers provide apps or websites to monitor the power output of their units. In many cases, these are proprietary; however this is not always the case. Following the demise of Enecsys, and the subsequent closure of their site; a number of private sites such as Enecsys-Monitoring[28] sprung up to enable owners to continue to monitor their systems.

Three-phase microinverters

[edit]Efficient conversion of DC power to AC requires the inverter to store energy from the panel while the grid's AC voltage is near zero, and then release it again when it rises. This requires considerable amounts of energy storage in a small package. The lowest-cost option for the required amount of storage is the electrolytic capacitor, but these have relatively short lifetimes normally measured in years, and those lifetimes are shorter when operated hot, like on a rooftop solar panel. This has led to considerable development effort on the part of microinverter developers, who have introduced a variety of conversion topologies with lowered storage requirements, some using the much less capable but far longer lived thin film capacitors where possible.

Three-phase electric power represents another solution to the problem. In a three-phase circuit, the power does not vary between (say) +120 to -120 V between two lines, but instead varies between 60 and +120 or -60 and -120 V, and the periods of variation are much shorter. Inverters designed to operate on three phase systems require much less storage.[29][30] A three-phase microinverter, using zero-voltage switching, can also offer higher circuit density and lower cost components, while improving conversion efficiency to over 98%, better than the typical one-phase peak around 96%.[31]

Three-phase systems, however, are generally only seen in industrial and commercial settings. These markets normally install larger arrays, where price sensitivity is the highest. Uptake of three-phase micros, in spite of any theoretical advantages, appears to be very low.

Portable uses

[edit]Foldable solar panel with AC microinverters can be used to recharge laptops and some electric vehicles.

History

[edit]The microinverter concept has been in the solar industry since its inception. However, flat costs in manufacturing, like the cost of the transformer or enclosure, scaled favorably with size, and meant that larger devices were inherently less expensive in terms of price per watt. Small inverters were available from companies like ExelTech and others, but these were simply small versions of larger designs with poor price performance, and were aimed at niche markets.

Early examples

[edit]

In 1991 the US company Ascension Technology started work on what was essentially a shrunken version of a traditional inverter, intended to be mounted on a panel to form an AC panel. This design was based on the conventional linear regulator, which is not particularly efficient and dissipates considerable heat. In 1994 they sent an example to Sandia Labs for testing.[32] In 1997, Ascension partnered with US panel company ASE Americas to introduce the 300 W SunSine panel.[33]

Design of, what would today be recognized as a "true" microinverter, traces its history to late 1980s work by Werner Kleinkauf at the ISET (Institut für Solare Energieversorgungstechnik), now Fraunhofer Institute for Wind Energy and Energy System Technology. These designs were based on modern high-frequency switching power supply technology, which is much more efficient. His work on "module integrated converters" was highly influential, especially in Europe.[34]

In 1993 Mastervolt introduced their first grid-tie inverter, the Sunmaster 130S, based on a collaborative effort between Shell Solar, Ecofys and ECN. The 130 was designed to mount directly to the back of the panel, connecting both AC and DC lines with compression fittings. In 2000, the 130 was replaced by the Soladin 120, a microinverter in the form of an AC adapter that allows panels to be connected simply by plugging them into any wall socket.[35]

In 1995, OKE-Services designed a new high-frequency version with improved efficiency, which was introduced commercially as the OK4-100 in 1995 by NKF Kabel, and re-branded for US sales as the Trace Microsine.[36] A new version, the OK4All, improved efficiency and had wider operating ranges.[37]

In spite of this promising start, by 2003 most of these projects had ended. Ascension Technology was purchased by Applied Power Corporation, a large integrator. APC was in turn purchased by Schott in 2002, and SunSine production was canceled in favor of Schott's existing designs.[38] NKF ended production of the OK4 series in 2003 when a subsidy program ended.[39] Mastervolt[40] has moved on to a line of "mini-inverters" combining the ease-of-use of the 120 in a system designed to support up to 600 W of panels.[41]

Enphase

[edit]In the aftermath of the 2001 Telecoms crash, Martin Fornage of Cerent Corporation was looking for new projects. When he saw the low performance of the string inverter for the solar array on his ranch, he found the project he was looking for. In 2006 he formed Enphase Energy with another Cerent engineer, Raghu Belur, and they spent the next year applying their telecommunications design expertise to the inverter problem.[42]

Released in 2008, the Enphase M175 model was the first commercially successful microinverter. A successor, the M190, was introduced in 2009, and the latest model, the M215, in 2011. Backed by $100 million in private equity, Enphase quickly grew to 13% marketshare by mid-2010, aiming for 20% by year-end.[42] They shipped their 500,000th inverter in early 2011,[43] and their 1,000,000th in September of the same year.[44] In early 2011, they announced that re-branded versions of the new design will be sold by Siemens directly to electrical contractors for widespread distribution.[45]

Enphase has entered an agreement with EnergyAustralia, to market its micro-inverter technology.[46]

Major players

[edit]Enphase's success did not go unnoticed, and since 2010 a host of competitors came and largely left the space. Many of the products were identical to the M190 in specs, and even in the casing and mounting details.[47] Some differentiate by competing head-to-head with Enphase in terms of price or performance,[48] while others are attacking niche markets.[49]

Larger firms also stepped into the field: SMA, Enecsys and iEnergy.

OKE-Services updated OK4-All product was bought by SMA in 2009 and released as the SunnyBoy 240 after an extended gestation period,[50] while Power-One has introduced the AURORA 250 and 300.[51] Other major players around 2010 included Enecsys and SolarBridge Technologies, especially outside the North American market. In 2021, the only microinverter made in the USA is from Chilicon Power.[52] Since 2009, several companies from Europe to China, including major central inverter manufacturers, have launched microinverters—validating the microinverter as an established technology and one of the biggest technology shifts in the PV industry in recent years.[53]

APsystems is marketing inverters for up to four solar modules per microinverter, including the three-phase YC1000 with an AC output of up to 1130 Watts to.[54]

The number of manufacturers has dwindled over the years, both by attrition and consolidation. In 2019, the few remaining include Enphase which purchased SolarBridge in 2021, Omnik Solar[55] and Chilicon Power (acquired by Generac in July 2021).[56]

In July 2021 the list of major PV companies who have partnered with microinverter companies to produce and sell AC solar panels include BenQ, Canadian Solar, LG, NESL, SunPower, Sharp Solar, Suntech, Siemens, Trina Solar and Qcells.[57][58]

Market

[edit]As of 2019, conversion efficiency for state-of-the-art solar converters reached more than 98 percent. While string inverters are used in residential to medium-sized commercial PV systems, central inverters cover the large commercial and utility-scale market. Market-share for central and string inverters are about 36 percent and 61 percent, respectively, leaving less than 2 percent to micro-inverters.[59]

| Type | Power | Efficiency(a) | Market Share(b) |

Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| String inverter | up to 150 kWp(c) | 98% | 61.6% | Cost(b) €0.05-0.17 per watt-peak. Easy to replace. |

| Central inverter | above 80 kWp | 98.5% | 36.7% | €0.04 per watt-peak. High reliability. Often sold along with a service contract. |

| Micro-inverter | module power range | 90%–97% | 1.7% | €0.29 per watt-peak. Ease-of-replacement concerns. |

| DC/DC converter (Power optimizer) |

module power range | 99.5% | 5.1% | €0.08 per watt-peak. Ease-of-replacement concerns. Inverter is still needed. |

| Source: data by IHS Markit 2020, remarks by Fraunhofer ISE 2020, from: Photovoltaics Report 2020, p. 39, PDF[59] Notes: (a)best efficiencies displayed, (b)market-share and cost per watt are estimated, (c)kWp = kilowatt-peak, (d) Total Market Share is greater than 100% because DC/DC converters are required to be paired with string inverters | ||||

Price declines

[edit]The period between 2009 and 2012 included unprecedented downward price movement in the PV market. At the beginning of this period, wholesale pricing for panels was generally around $2.00 to $2.50/W, and inverters around 50 to 65 cents/W. By the end of 2012, panels were widely available in wholesale at 65 to 70 cents, and string inverters around 30 to 35 cents/W.[60] In comparison, microinverters have proven relatively immune to these same sorts of price declines, moving from about 65 cents/W to 50 to 55 once cabling is factored in. This could lead to widening losses as the suppliers attempt to remain competitive.[61]

See also

[edit]- AC power plugs and sockets § Hybrid and universal sockets

- Amphenol connector

- Charge controller

- DC-to-DC charger

- DC-to-DC converter

- Grid-tie inverter

- Junction box

- MC4 connector

- Nanoinverter

- Off-the-grid

- Open-source hardware

- Power inverter

- Power optimizer

- Switch

- Synchronverter

- Three-phase micro-inverter

- Waterproof

- Zigbee

Notes

[edit]- ^ Since 2011 an increasing number of panels and string inverters are rated to 1000 V instead of the older 600 V standard. This allows longer strings to be created, lowering system cost by avoiding the need for additional "combiners". This standard is not universal, but is being rapidly adopted As of 2014[update]

References

[edit]- Li, Quan; P. Wolfs (2008). "A Review of the Single Phase Photovoltaic Module Integrated Converter Topologies with Three Different DC Link Configurations". IEEE Transactions on Power Electronics. 23 (3): 1320–1333. Bibcode:2008ITPE...23.1320L. doi:10.1109/tpel.2008.920883. hdl:20.500.11937/5977. S2CID 10910991.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Chen, Lin; A. Amirahmadi; Q. Zhang; N. Kutkut; I. Batarseh (2014). "Design and Implementation of Three-phase Two-stage Grid-connected Module Integrated Converter". IEEE Transactions on Power Electronics. 29 (8): 3881–3892. Bibcode:2014ITPE...29.3881C. doi:10.1109/tpel.2013.2294933. S2CID 25846066.

- Amirahmadi, Ahmadreza; H. Hu; A. Grishina; Q. Zhang; L. Chen; U. Somani; I. Batarseh (2014). "ZVS BCM Current Controlled Three-Phase Micro-inverter". IEEE Transactions on Power Electronics. 29 (4): 2124–2134. doi:10.1109/tpel.2013.2271302. S2CID 43665974.

- Manufacturer's specification of YC1000 (for 4 modules) Archived 29 June 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Solar Cells and their Applications Second Edition, Lewis Fraas, Larry Partain, Wiley, 2010, ISBN 978-0-470-44633-1, Section 10.2.

- ^ "3 Types of Solar Inverters Explained". do it yourself. Retrieved 15 February 2017.

- ^ "Best Solar Inverters Australia 2025". isolux.com.au. Retrieved 21 May 2015.

- ^ "Invert your thinking: Squeezing more power out of your solar panels". scientificamerican.com. Retrieved 9 June 2011.

- ^ "Comparison of Photovoltaic Array Maximum Power Point Tracking Techniques" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 July 2010.

- ^ Benanti, Travis L.; Venkataraman, D. (25 April 2005). "Organic Solar Cells: An Overview Focusing on Active Layer Morphology" (PDF). Photosynthesis Research. 87 (1): 73–81. doi:10.1007/s11120-005-6397-9. PMID 16408145. S2CID 10436403. Retrieved 27 August 2013.

- ^ "Evaluation of Micro Controller Based Maximum Power Point Tracking Methods Using dSPACE Platform" (PDF). itee.uq.edu.au. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 14 June 2011.

- ^ Hohm, D. P.; Ropp, M. E. (2003). "Comparative Study of Maximum Power Point Tracking Algorithms". Progress in Photovoltaics: Research and Applications. 11: 47–62. doi:10.1002/pip.459.

- ^ Shabani, Issam; Chaaban, Mohammad (2020), "Technical Overview of the Net Metering in Lebanon", Trends in Renewable Energy, 6 (3): 266–284, doi:10.17737/tre.2020.6.3.00126, S2CID 228963476

- ^ Photovoltaics: Design and Installation Manual. Newsociety Publishers. 2004. p. 80.

- ^ "Summary Report on the DOE High-tech Inverter Workshop" (PDF). Sponsored by the US Department of Energy, prepared by McNeil Technologies. eere.energy.gov. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 February 2012. Retrieved 10 June 2011.

- ^ "Development of a High-Efficiency Solar Micro-Inverter" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 July 2014. Retrieved 27 August 2013.

- ^ "A Side-by-Side Comparison of Micro and Central Inverters in Shaded and Unshaded Conditions" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 27 August 2013.

- ^ Where Microinverter and Panel Manufacturer Meet Up Zipp, Kathleen "Solar Power World", US, 24 October 2011.

- ^ Market and Technology Competition Increases as Solar Inverter Demand Peaks Greentech Media Staff from GTM Research. Greentech Media, USrs, 26 May 2009. Retrieved on 4 April 2012.

- ^ SolarWorld's SW 245 Archived 13 August 2012 at the Wayback Machine is a typical modern module, using 6" cells in a 6 by 10 arrangement and a of 30.8 V

- ^ SMA's SunnyBoy Archived 8 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine series is available in US and European versions, and the recommended input range is 500 to 600 VDC.

- ^ Productive. Enphase, 2011 (archived)

- ^ Performance of PV Topologies under Shaded Conditions. SolarEdge, April 2020

- ^ Muenster, R. 2009-02-02 “Shade Happens” Renewable Energy World.com. Retrieved 2009-03-09.

- ^ "Increase Power Production" Archived 16 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine, eIQ Energy

- ^ "OptiTrac Global Peak | SMA Solar".

- ^ a b "Enphase Microinverter M190", Enphase Energy

- ^ "2018 Solar Panels Cost Per Watt Guide". Archived from the original on 12 April 2019. Retrieved 31 January 2024.

- ^ SolarBridge and PV Microinverter Reliability[permanent dead link], Wesoff, Eric.Greentech Media, US, 2 June 2011. Retrieved on 4 April 2012.

- ^ Micro inverter model ranges stepping up roughly in 10 Watt or 20 Watt increments Archived 26 April 2015 at archive.today. Ekoleden. Retrieved 2012-12-07.

- ^ "All systems", the very first entry on 25-March-2011 was a single-panel system

- ^ "Enecsys Monitor Home". Enecsys Monitoring.

- ^ Li, Quan; P. Wolfs (2008). "A Review of the Single Phase Photovoltaic Module Integrated Converter Topologies with Three Different DC Link Configurations". IEEE Transactions on Power Electronics. 23 (3): 1320–1333. Bibcode:2008ITPE...23.1320L. doi:10.1109/TPEL.2008.920883. hdl:20.500.11937/5977. S2CID 10910991.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Chen, Lin; A. Amirahmadi; Q. Zhang; N. Kutkut; I. Batarseh (2014). "Design and Implementation of Three-phase Two-stage Grid-connected Module Integrated Converter". IEEE Transactions on Power Electronics. 29 (8): 3881–3892. Bibcode:2014ITPE...29.3881C. doi:10.1109/TPEL.2013.2294933. S2CID 25846066.

- ^ Amirahmadi, Ahmadreza; H. Hu; A. Grishina; Q. Zhang; L. Chen; U. Somani; I. Batarseh (2014). "ZVS BCM Current Controlled Three-Phase Micro-inverter". IEEE Transactions on Power Electronics. 29 (4): 2124–2134. doi:10.1109/TPEL.2013.2271302. S2CID 43665974.

- ^ Katz, p. 3

- ^ Katz, p. 4

- ^ "Appreciation Prof. Dr. Werner Kleinkauf", EUROSOLAR

- ^ "Connect to the Sun"[permanent dead link], Mastervolt, p. 7

- ^ "Utility Line Tie Power", Trace Engineering, p. 3

- ^ "OK4All" Archived 28 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine, OK-Services

- ^ "GreenRay Solar, History of the Technology". Greenraysolar.com. Retrieved 2012-12-07.

- ^ Katz, p. 7

- ^ "Системы электро питания - Mastervolt Украина". Mastervolt.

- ^ Connect to the Sun., p. 9. Mastervolt, 2009 (2.8 MB) via

- ^ a b Kerry Dolan, "Enphase's Rooftop Solar Revolution", Forbes, 8 November 2010

- ^ ""Enphase Energy surpasses 500,000 solar PV inverter units shipped"". Archived from the original on 23 July 2011.

- ^ ""Journey to the 1,000,000th Microinverter"". Archived from the original on 26 April 2015. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ^ Yuliya Chernova, "Will Solar Become A Standard Offering In Construction?", Wall Street Journal, 2 February 2011

- ^ Parkinson, Giles (12 March 2015). "Enphase says storage already at "parity" in some Australian markets". RenewEconomy.

- ^ See this product Archived 3 September 2010 at the Wayback Machine for instance, or this one, and compare to photos of the M190

- ^ SPARQ's design Archived 18 June 2022 at the Wayback Machine uses a single high-power digital signal controller with few supporting components

- ^ Like Island Technology's system aimed at thin-film modules which have different voltage ranges than conventional cells

- ^ "OK4ALL". Archived from the original on 28 June 2010.

- ^ "Power-One launches 300W Microinverter and DC/DC Power Optimizer". power-one.com. 4 May 2011. Archived from the original on 21 February 2014.

- ^ "Chilicon Power". chiliconpower. Retrieved 24 August 2021.

- ^ Wesoff, Eric (26 October 2010). "Microinverter, Panel Optimizer and Solar BoS Startup News". greentechmedia. Retrieved 24 August 2021.

- ^ "Solar Microinverters". apsystems. 3 September 2017. Retrieved 24 August 2021.

- ^ "A Story of Renowned Inverter Company:Omnik Solar". 4 March 2024.

- ^ "Generac Enters Microinverter Market with Acquisition of Chilicon Power". generac.com. 6 July 2021. Retrieved 24 August 2021.

- ^ "Micro Inverters and AC Solar Panels: The Future of Solar Power?". solarquotes.com.au. Retrieved 24 August 2021.

- ^ "Enphase Microinverters Join Siemens' Distribution Family". 2011.

- ^ a b "PHOTOVOLTAICS REPORT" (PDF). Fraunhofer Institute for Solar Energy Systems. 16 September 2020. p. 39.

- ^ Galen Barbose, Naïm Darghouth, Ryan Wiser, "Tracking the Sun V" Archived 2 December 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Lawrence Berkeley Lab, 2012

- ^ Wesoff, Eric (8 August 2012). "Enphase Update: Stock Price Slammed After PV Microinverter Firm Loses CFO, Losses Widen". greentechmedia.

- Bibliography

- David Katz. "Micro-Inverters and AC Modules" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 July 2011. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Solar inverter panels at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Solar inverter panels at Wikimedia Commons

- Model based control of photovoltaic inverter Simulation, description and working VisSim source code diagram

- Micro-inverters vs. Central Inverters: Is There a Clear Winner?, podcast debating the ups and downs of the microinverter approach.

- Design and Implementation of Three-phase Two-stage Grid-connected Module Integrated Converter

- A Review of the Single Phase Photovoltaic Module Integrated Converter Topologies with Three Different DC Link Configurations

- ZVS BCM Current Controlled Three-Phase Micro-inverter

- APsystems microinverter YC1000-3 for 4 modules (900 Watt AC) Archived 29 June 2018 at the Wayback Machine