Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Straw man

View on Wikipedia

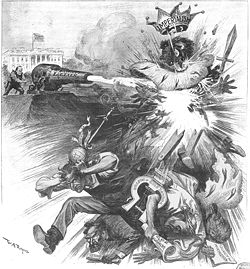

A straw man fallacy (sometimes written as strawman) is the informal fallacy of refuting an argument different from the one actually under discussion, while not recognizing or acknowledging the distinction.[1] One who engages in this fallacy is said to be "attacking a straw man".

The typical straw man argument creates the illusion of having refuted or defeated an opponent's proposition through the covert replacement of it with a different proposition (i.e., "stand up a straw man") and the subsequent refutation of that false argument ("knock down a straw man"), instead of the opponent's proposition.[2][3] Straw man arguments have been used throughout history in polemical debate, particularly regarding highly charged emotional subjects.[4]

Straw man tactics in the United Kingdom may also be known as an Aunt Sally, after a pub game of the same name, where patrons throw sticks or battens at a post to knock off a skittle balanced on top.[5][6]

Overview

[edit]The straw man fallacy occurs in the following pattern of argument:

- Person 1 asserts proposition X.

- Person 2 argues against a superficially similar proposition Y, as though an argument against Y were an argument against X.

This reasoning is a fallacy of relevance: it fails to address the proposition in question by misrepresenting the opposing position.

For example:

- Quoting an opponent's words out of context—i.e., choosing quotations that misrepresent the opponent's intentions (see fallacy of quoting out of context).[3]

- Presenting someone who defends a position poorly as the defender, then denying that person's arguments—thus giving the appearance that every upholder of that position (and thus the position itself) has been defeated.[2]

- Oversimplifying an opponent's argument, then attacking this oversimplified version.

- Exaggerating (sometimes grossly) an opponent's argument, then attacking this exaggerated version.

Contemporary revisions

[edit]In 2006, Robert Talisse and Scott Aikin expanded the application and use of the straw man fallacy beyond that of previous rhetorical scholars, arguing that the straw man fallacy can take two forms: the original form that misrepresents the opponent's position, which they call the representative form; and a new form they call the selection form.

The selection form focuses on a partial and weaker (and easier to refute) representation of the opponent's position. Then the easier refutation of this weaker position is claimed to refute the opponent's complete position. They point out the similarity of the selection form to the fallacy of hasty generalization, in which the refutation of an opposing position that is weaker than the opponent's is claimed as a refutation of all opposing arguments. Because they have found significantly increased use of the selection form in modern political argumentation, they view its identification as an important new tool for the improvement of public discourse.[7]

Aikin and Casey expanded on this model in 2010, introducing a third form. Referring to the "representative form" as the classic straw man, and the "selection form" as the weak man, the third form is called the hollow man. A hollow man argument is one that is a complete fabrication, where both the viewpoint and the opponent expressing it do not in fact exist, or at the very least the arguer has never encountered them. Such arguments frequently take the form of vague phrasing such as "some say," "someone out there thinks" or similar weasel words, or it might attribute a non-existent argument to a broad movement in general, rather than an individual or organization.[8][9]

Nutpicking

[edit]A variation on the selection form, or "weak man" argument, that combines with an ad hominem and fallacy of composition is nutpicking (or nut picking), a neologism coined by Kevin Drum.[10] A combination of "nut" (i.e., insane person) and "cherry picking", as well as a play on the word "nitpicking", nut picking refers to intentionally seeking out extremely fringe, non-representative statements from members of an opposing group and parading these as evidence of that entire group's incompetence or irrationality.[8]

Steelmanning

[edit]A steel man argument (or steelmanning) is the opposite of a straw man argument. Steelmanning is the practice of applying the rhetorical principle of charity through addressing the strongest form of the other person's argument, even if it is not the one they explicitly presented. Creating the strongest form of the opponent's argument may involve removing flawed assumptions that could be easily refuted or developing the strongest points which counter one's own position. Developing counters to steel man arguments may produce a stronger argument for one's own position.[11]

Examples

[edit]In a 1977 appeal of a U.S. bank robbery conviction, a prosecuting attorney said in his oral argument:[12] "I submit to you that if you can't take this evidence and find these defendants guilty on this evidence then we might as well open all the banks and say, 'Come on and get the money, boys,' because we'll never be able to convict them." This was a straw man designed to alarm the appellate judges; the chance that the precedent set by one case would literally make it impossible to convict any bank robbers is remote.

Another example of a strawman argument is U.S. president Richard Nixon's 1952 "Checkers speech".[13][14] When campaigning for vice president in 1952, Nixon was accused of having appropriated $18,000 in campaign funds for his personal use. In a televised response, based on Franklin D. Roosevelt's Fala speech, he spoke about another gift, a dog he had been given by a supporter:[13][14]

It was a little cocker spaniel dog, in a crate he had sent all the way from Texas, black and white, spotted, and our little girl Tricia, six years old, named it Checkers. And, you know, the kids, like all kids, loved the dog, and I just want to say this right now, that, regardless of what they say about it, we are going to keep it.

This was a straw man response; his critics had never criticized the dog as a gift or suggested he return it. This argument was successful at distracting many people from the funds and portraying his critics as nitpicking and heartless. Nixon received an outpouring of public support and remained on the ticket. He and Eisenhower were later elected.

Christopher Tindale presents, as an example, the following passage from a draft of a bill (HCR 74) considered by the Louisiana State Legislature in 2001:[15]

Whereas, the writings of Charles Darwin, the father of evolution, promoted the justification of racism, and his books On the Origin of Species and The Descent of Man postulate a hierarchy of superior and inferior races. ... Therefore, be it resolved that the legislature of Louisiana does hereby deplore all instances and all ideologies of racism, does hereby reject the core concepts of Darwinist ideology that certain races and classes of humans are inherently superior to others, and does hereby condemn the extent to which these philosophies have been used to justify and approve racist practices.

Tindale comments that "the portrait painted of Darwinian ideology is a caricature, one not borne out by any objective survey of the works cited." The fact that similar misrepresentations of Darwinian thinking have been used to justify and approve racist practices is beside the point: the position that the legislation is attacking and dismissing is a straw man. In subsequent debate, this error was recognized, and the eventual bill omitted all mention of Darwin and Darwinist ideology.[15] Darwin passionately opposed slavery and worked to intellectually confront the notions of "scientific racism" that were used to justify it.[16]

Throughout the 20th century, and also in the 21st century thus far,[17] there have been innumerable instances when right-wing political leaders and commentators used communism as a straw man while denouncing the proposals of centrists, moderate liberals, or even moderate conservatives. They sought to portray valid criticism of their own right-wing policies as expressions of communist ideology when in reality, most of the critics in question were not even socialists, much less communists. The use of communism as a straw man was a common and effective (though fallacious) talking point by conservative leaders in many western countries such as the United Kingdom, Germany, and most especially the United States.[18][19][20]

Etymology

[edit]As a fallacy, the identification and name of straw man arguments are of relatively recent date, although Aristotle makes remarks that suggest a similar concern.[21] Isaac Watts writes in his Logick (1724): "They dress up the opinion of their adversary as they please, and ascribe sentiments to him which he doth not acknowledge; and when they have with a great deal of pomp attacked and confounded these images of straw of their own making, they triumph over their adversary as though they had utterly confuted his opinion."[22]

Douglas N. Walton identified "the first inclusion of it we can find in a textbook as an informal fallacy" in Stuart Chase's Guides to Straight Thinking from 1956 (p. 40).[21][15] By contrast, Hamblin's classic text Fallacies (1970) neither mentions it as a distinct type, nor even as a historical term.[21][15]

The term's origins are a matter of debate, though the usage of the term in rhetoric suggests a human figure made of straw that is easy to knock down or destroy—such as a military training dummy, scarecrow, or effigy.[23] A common but false etymology is that it refers to men who stood outside courthouses with a straw in their shoe to signal their willingness to be a false witness.[24] The Online Etymology Dictionary states that the term "man of straw" can be traced back to 1620 as "an easily refuted imaginary opponent in an argument".[25]

Related usage

[edit]Reverend William Harrison, in A Description of England (1577), complained that when men lived in houses of willow they were men of oak, but now they lived in houses of oak and had become men of willow and "a great manie altogither of straw, which is a sore alteration [i.e. a sad change]".[26] The phrase 'men of straw' appears to refer to pampered softness and a lack of character, rather than the modern meaning.

Martin Luther blames his opponents for misrepresenting his arguments in his work On the Babylonian Captivity of the Church (1520):

| Latin | Unattributed English translation | Philadelphia Edition translation |

|---|---|---|

| Respondeo, id genus disputandi omnibus familiare esse, qui contra Lutherum scribunt, ut hoc asserant quod impugnant, aut fingant quod impugnent.[27] | I answer that this kind of discussion is familiar to all who write against Luther, so they can assert (or: 'plant', literally: 'sow') what they attack, or pretend what they attack. | My answer is, that this sort of argument is common to all those who write against Luther. They assert the very things they assail, or they set up a man of straw whom they may attack.[28][29] |

In the quote, he responds to arguments of the Roman Catholic Church and clergy attempting to delegitimize his criticisms, specifically on the correct way to serve the Eucharist. The church claimed Martin Luther is arguing against serving the Eucharist according to one type of serving practice; Martin Luther states he never asserted that in his criticisms towards them and in fact they themselves are making this argument. Luther's Latin text does not use the phrase "man of straw", but it is used in a widespread early 20th century English translation of his work, the Philadelphia Edition.[30]

See also

[edit]- Ad hominem – Attacking the person rather than the argument

- Begging the question – Logic founded on unproven premises

- Devil's advocate – Figure of speech and former official position within the Catholic Church

- Cherry picking – Fallacy of incomplete evidence

- False attribution – Credit for a work given to the wrong person

- Misquotation – Repetition of one expression as part of another one

- Cognitive bias – Systematic pattern of deviation from norm or rationality in judgment

- Concern troll – Person who sows discord online

- Cratylism – Philosophical theory

- Fallacy of quoting out of context – Informal fallacy

- List of fallacies

- Media manipulation – Techniques in which partisans create an image that favours their interests

- Paper tiger – Chinese phrase for an ineffectual threat

- Pooh-pooh – Fallacy in informal logic

- Red herring – Fallacious approach to mislead an audience

- Tilting at windmills – Idiom meaning "attacking imaginary enemies"

- Trivial objections – Fallacy in informal logic

References

[edit]- ^ Downes, Stephen. "The Logical Fallacies". Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 25 February 2016.

- ^ a b Pirie, Madsen (2007). How to Win Every Argument: The Use and Abuse of Logic. UK: Continuum International Publishing Group. pp. 155–157. ISBN 978-0-8264-9894-6.

- ^ a b "The Straw Man Fallacy". fallacyfiles.org. Retrieved 12 October 2007.

- ^ Demir, Yeliz (2018). "Derailment of strategic maneuvering in a multi-participant TV debate: The fallacy of ignoratio elenchi". Dil ve Edebiyat Dergisi. 15 (1): 25–58.

- ^ Lindley, Dennis V. (2006). Understanding Uncertainty. John Wiley & Sons. p. 80. ISBN 978-0-470-04383-7. Retrieved 25 February 2016.

- ^ A. W. Sparkes (1991). Talking Philosophy: A Wordbook. Routledge. p. 104. ISBN 978-0-415-04223-9. Retrieved 25 February 2016.

- ^ Talisse, Robert; Aikin, Scott (September 2006). "Two Forms of the Straw Man". Argumentation. 20 (3). Kluwer Academic Publishers: 345–352. doi:10.1007/s10503-006-9017-8. ISSN 1572-8374. S2CID 15523437.

- ^ a b Aikin, Scott; Casey, John (March 2011). "Straw Men, Weak Men, and Hollow Men". Argumentation. 25 (1). Springer Netherlands: 87–105. doi:10.1007/s10503-010-9199-y. ISSN 1572-8374. S2CID 143594966.

- ^ Douglas Walton (2013). Methods of Argumentation. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-43519-3.

- ^ Drum, Kevin (11 August 2006). "Nutpicking". Washington Monthly.

- ^ Friedersdorf, Conor (26 June 2017). "The Highest Form of Disagreement". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 6 June 2021.

- ^ Bosanac, Paul (2009). Litigation Logic: A Practical Guide to Effective Argument. American Bar Association. p. 393. ISBN 978-1616327101.

- ^ a b Waicukauski, Ronald J.; Paul Mark Sandler; JoAnne A. Epps (2001). The Winning Argument. American Bar Association. pp. 60–61. ISBN 1570739382. Retrieved 25 February 2016.

- ^ a b Rottenberg, Annette T.; Donna Haisty Winchell (2011). The Structure of Argument. MacMillan. pp. 315–316. ISBN 978-0312650698. Retrieved 25 February 2016.

- ^ a b c d Tindale, Christopher W. (2007). Fallacies and Argument Appraisal. Cambridge University Press. pp. 19–28. ISBN 978-0-521-84208-2.

- ^ Adrian Desmond and James Moore (2009). Darwin's Sacred Cause: How a Hatred of Slavery Shaped Darwin's Views on Human Evolution. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- ^ Sarat, Austin. "Why Donald Trump Says his Enemies are 'Communists'". Politico, 22 June 2023. Retrieved 7 March 2025..

- ^ "McCarthyism and the Red Scare". Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Retrieved 7 March 2025..

- ^ Mukhergee, Rudrangshu. "How Fear of Communism Led to the Rise of Hitler, Nazism, and World War Two". The Wire, India, 5 November 2021. Retrieved 7 March 2025.

- ^ Boot, Max. "Ronald Reagan Was More Ideological – and More Pragmatic – Than You Think". The Washington Post, 27 August 2024. Retrieved 7 March 2025.

- ^ a b c Douglas Walton, "The straw man fallacy". In Logic and Argumentation, eds. Johan van Bentham, Frans H. van Eemeren, Rob Grootendorst and Frank Veltman. Amsterdam, Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences, North-Holland, 1996. pp. 115–128

- ^ Watts, Isaac (1726) [1724]. Logick: Or, the Right Use of Reason in the Inquiry After Truth (2nd ed.). pp. 314–315 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Damer, T. Edward (1995). Attacking Faulty Reasoning: A Practical Guide to Fallacy-Free Arguments. Wadsworth. pp. 157–159.

- ^ Brewer, E. Cobham (1898). "Man of Straw (A)". Dictionary of Phrase and Fable. Retrieved 13 May 2009.

- ^ "straw man". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ Harrison, William (1994). Edelen, George (ed.). The Description of England: The Classic Contemporary Account of Tudor Social Life. Folger Shakespeare Library, Dover Publications. p. 276. ISBN 978-0-486-28275-6. Retrieved 14 September 2023.

- ^ Luther, Martin (1520). "De captivitate ecclesiae babylonica" [On the Babylonian Captivity of the Church] (online text based on Weimar Edition, vol. 6, p. 497). martinluther.dk (in Latin). Ricardt Riis. p. section 15.

- ^ Luther, Martin (1915). Works of Martin Luther : With Introductions and Notes, Volume 2. A.J. Holman Company. p. 173. ISBN 978-0-7222-2123-5. Retrieved 14 September 2023.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Luther, Martin. "The Babylonian Captivity of the Church [from the Philadelphia Edition of Luther's works]". lutherdansk.dk. Robert E. Smith, Project Wittenberg, Wesley R. Smith, Lucas C. Smith. Retrieved 14 September 2023.

- ^ Luther, M. et al. (1915–1943) Works of Martin Luther – With Introduction and Notes. Philadelphia: Muhlenberg Press

External links

[edit]- Straw Man at Fallacy Check, with examples

- The Straw Man Fallacy at the Fallacy Files

- Straw Man, more examples of straw man arguments

- Nut picking at Fallacy Check, with examples