Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Subscapularis muscle

View on Wikipedia

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2021) |

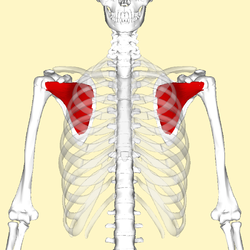

| Subscapularis muscle | |

|---|---|

Subscapularis muscle (in red). Ribs are shown as semi-transparent. Anterior view. | |

The subscapularis is difficult to see from the front (labeled middle right) | |

| Details | |

| Origin | Subscapular fossa |

| Insertion | Lesser tubercle of humerus |

| Artery | Subscapular artery |

| Nerve | Upper subscapular nerve, lower subscapular nerve (C5, C6) |

| Actions | Internally rotates and adducts humerus; stabilizes shoulder |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | musculus subscapularis |

| TA98 | A04.6.02.012 |

| TA2 | 2460 |

| FMA | 13413 |

| Anatomical terms of muscle | |

The subscapularis is a large triangular muscle which fills the subscapular fossa and inserts into the lesser tubercle of the humerus and the front of the capsule of the shoulder-joint.

Structure

[edit]The subscapularis is covered by a dense fascia which attaches to the scapula at the margins of the subscapularis' attachment (origin) on the scapula.[1]

The muscle's fibers pass laterally from its origin before coalescing into a tendon of insertion.[citation needed] The tendon intermingles with the glenohumeral (shoulder) joint capsule.[1]

A bursa (which communicates with the cavity of the shoulder joint[1][2] via an aperture in the joint capsule[2]) intervenes between the tendon and a bare area at the lateral angle of the scapula[1]/the neck of the scapula.[2] The subscapularis (supraserratus) bursa separates the subscapularis is from the serratus anterior.[2]

Origin

[edit]It arises from its medial two-thirds of the costal surface of the scapula, the intermuscular septa (which create ridges upon the scapula),[1] and the lower two-thirds of the groove on the axillary border (subscapular fossa) of the scapula.[citation needed]

Some fibers arise from tendinous laminae, which intersect the muscle and are attached to ridges on the bone; others from an aponeurosis, which separates the muscle from the teres major and the long head of the triceps brachii.[citation needed]

Insertion

[edit]It inserts onto the lesser tubercle of the humerus[1] and the anterior part of the shoulder-joint capsule. Tendinous fibers extend to the greater tubercle with insertions into the bicipital groove.[citation needed]

Innervation

[edit]The subscapularis is supplied by the upper and lower subscapular nerves (C5-C6), branches of the posterior cord of the brachial plexus.[1]

Actions/movements

[edit]The subscapularis medially (internally) rotates the humerus (acting here as a prime mover)[1] and adducts it. When the arm is raised, it draws the humerus forward and downward.[citation needed]

Function

[edit]The subscapularis stabilises the shoulder joint by contributing to the fixation of the proximal humerus during movements of the elbow, wrist, and hand.[1] It is a powerful defense to the front of the shoulder-joint, preventing displacement of the head of the humerus.[citation needed]

Clinical significance

[edit]Examination

[edit]It is difficult to isolate the action of the subscapularis from other medial rotators of the shoulder joint; there is no satisfactory test for this muscle.[1] The Gerber Lift-off test is the established clinical test for examination of the subscapularis.[3] The bear hug test (internal rotation while palm is held on opposite shoulder and elbow is held in a position of maximal anterior translation) for subscapularis muscle tears has high sensitivity. Positive bear-hug and belly press tests indicate significant tearing of subscapularis.[4]

Imaging

[edit]

There is no singularly imaging device or technique for a satisfying and complete subscapularis examination, but rather the combination of the sagittal oblique MRI / short-axis US and axial MRI / long-axis US planes seems to generate useful results. Additionally, lesser tuberosity bony changes have been associated with subscapularis tendon tears. Findings with cysts seem to be more specific and combined findings with cortical irregularities more sensitive.[5]

Another fact typically for the subscapularis muscle is the fatty infiltration of the superior portions, while sparing the inferior portions.

Since the long biceps tendon absents itself from the shoulder joint through the rotator cuff interval, it is easily possible to distinguish between the supraspinatus and the subscapularis tendon. Those two tendons build the interval sling.

Ultrasonography

[edit]Mack et al. developed an ultrasonographic procedure with which it is possible to explore almost the complete rotator cuff within six steps. It unveils clearly the whole area from the subedge of the subscapularis tendon until the intersection between the infraspinatus tendon and musculus teres minor. One of six steps does focus on the subscapularis tendon. In the first instance the examinator guides the applicator to the proximal humerus as perpendicularly as possible to the sulcus intertubercularis. Gliding now medially shows the insertion of the subscapularis tendon.[6]

Longitudinal plane of the musculus subscapularis and its tendon

[edit]The subscapularis tendon lies approximately 3 to 5 cm under the surface. Quite deep for ultrasonography, and therefore displaying through a highly penetrative 5 MHz linear applicator is worth a try. And it really turned out to ease a detailed examination of the muscle which just abuts to the scapula. However, the tendon of primary interest does not get mapped as closely as desired. As anatomical analysis showed, it is only by external rotation possible to see the ventral part of the joint socket and its labrum. While at the neutral position the tuberculum minus occludes the view. Summing up it is through an external arm rotation and a medially applied 5 MHz sector sonic head possible to display the ventral part of the joint socket and its labrum with notedly lower echogenicity.[7]

The following sectional planes are defined for the sonographic examination of the different shoulder joint structures:[8]

| Ventral transversal | Ventral sagittal medial | Ventral sagittal lateral | Lateral coronal | Lateral transversal/sagittal: | Dorsal transversal | Dorsal sagittal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| subscapularis muscle (longitudinal) | subscapularis muscle (transversal) | Intertub. sulcus with long head of biceps brachii (longitudinal) | supraspinatus muscle (longitudinal) | supraspinatus muscle (transversal) | infraspinatus muscle (longitudinal) | supraspinatus muscle (transversal) |

| Intertubercular sulcus with long head of biceps brachii (transversal) | Hill-Sachs-Lesio |

Tissue harmonic imaging

[edit]Primarily in abdominal imaging, tissue harmonic imaging (THI) gets more and more valued and used additionally to conventional ultrasonography.

THI involves the use of harmonic frequencies that originate within the tissue as a result of nonlinear wave front propagation and are not present in the incident beam. These harmonic signals may arise differently at anatomic sites with similar impedances and thus lead to higher contrast resolution." Along with higher contrast resolution it has an elevated signal-to-noise ratio and significantly reduced inter- and intraobserver variability compared with conventional US. Additionally it is possible to nearly eliminate ordinary US artifacts, i.e. side-lobe, near-field artifacts, reverberation artifacts. As aforementioned THI has already led to enhanced abdominal, breast, vascular and cardiac sonography.

For musculo-skeletal aspects THI has not been used that much, although this method features some useful potential. For example, for the still tricky discrimination between the presence of a hypoechoic defect and/or loss of the outer tendon convexity/non-visualization of the tendon, that is between partial- and full-thickness rotator cuff tears.

In comparison to a checking MR Arthrography Strobel K. et al. has arrived at the conclusion that through THI it is possible to achieve a generally improved visibility of joint and tendon surfaces, especially superior for subscapularis tendon abnormalities.[9]

Additional images

[edit]-

Subscapularis muscle (shown in red). Animation.

-

Same as the left, but the bones around the muscle are shown as semi-transparent.

-

Transverse section of thorax featuring subscapularis muscle

-

Diagram of the human shoulder joint

References

[edit]![]() This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 440 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 440 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Sinnatamby, Chummy (2011). Last's Anatomy (12th ed.). pp. 44–45. ISBN 978-0-7295-3752-0.

- ^ a b c d Milano, Giuseppe and Grasso, Andrea, Shoulder Arthroscopy: Principles and Practice Archived 27 April 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Springer Science & Business Media, Dec 16, 2013. ISBN 9781447154273. Accessed 2016-11-07.

- ^ Simons, Stephen; Dixon, J Bryan (3 April 2017). "Physical examination of the shoulder". UpToDate. Archived from the original on 20 April 2017. Retrieved 19 April 2017.

- ^ Barth, Johannes R.H.; Burkhart, Stephen S.; De Beer, Joe F. (October 2006). "The Bear-Hug Test: A New and Sensitive Test for Diagnosing a Subscapularis Tear". Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic and Related Surgery. 22 (10): 1076–1084. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2006.05.005. PMID 17027405.

- ^ Morag, Yoav; Jamadar, David A.; Miller, Bruce; Dong, Qian; Jacobson, Jon A. (2009). "The subscapularis: Anatomy, injury, and imaging". Skeletal Radiology. 40 (3): 255–69. doi:10.1007/s00256-009-0845-0. PMID 20033149. S2CID 13833846.

- ^ Mack, L A; Matsen, F A; Kilcoyne, R F; Davies, P K; Sickler, M E (1985). "US evaluation of the rotator cuff". Radiology. 157 (1): 205–9. doi:10.1148/radiology.157.1.3898216. PMID 3898216.

- ^ Katthagen BD. et al.. Schultersonographie. Stuttgart. ISBN 3-13-719401-6[page needed]

- ^ Thelen M. et al.. Radiologische Diagnostik der Verletzungen von Knochen und Gelenken. Stuttgart [etc.]. Georg Thieme. 1993. ISBN 3-13-778701-7[page needed]

- ^ Strobel, Klaus; Zanetti, Marco; Nagy, Ladislav; Hodler, Juerg (2004). "Suspected Rotator Cuff Lesions: Tissue Harmonic Imaging versus Conventional US of the Shoulder1". Radiology. 230 (1): 243–9. doi:10.1148/radiol.2301021517. PMID 14631052.