Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Thyrotropin-releasing hormone

View on Wikipedia| thyrotropin-releasing hormone | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

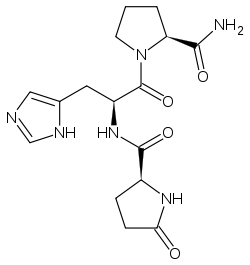

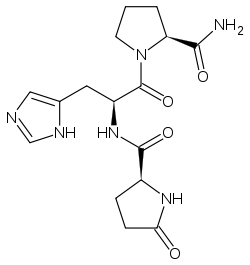

Structural formula of TRH | |||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||

| Symbol | TRH | ||||||

| NCBI gene | 7200 | ||||||

| HGNC | 12298 | ||||||

| OMIM | 275120 | ||||||

| RefSeq | NM_007117 | ||||||

| UniProt | P20396 | ||||||

| Other data | |||||||

| Locus | Chr. 3 q13.3-q21 | ||||||

| |||||||

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| ATC code | |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.041.934 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C16H22N6O4 |

| Molar mass | 362.390 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

Thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH) is a hypophysiotropic hormone produced by neurons in the hypothalamus that stimulates the release of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) as well as prolactin from the anterior pituitary.

TRH has been used clinically in diagnosis of hyperthyroidism,[1] and for the treatment of spinocerebellar degeneration and disturbance of consciousness in humans.[2] Its pharmaceutical form is called protirelin (INN) (/proʊˈtaɪrɪlɪn/).

Physiology

[edit]Synthesis and release

[edit]

TRH is synthesized within parvocellular neurons of the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus.[3] It is translated as a 242-amino acid precursor polypeptide that contains 6 copies of the sequence -Gln-His-Pro-Gly-, with both ends of the sequence flanked by Lys-Arg or Arg-Arg sequences.

To produce the mature form, a series of enzymes are required. First, a protease cleaves to the C-terminal side of the flanking Lys-Arg or Arg-Arg. Second, a carboxypeptidase removes the Lys/Arg residues leaving Gly as the C-terminal residue. Then, this Gly is converted into an amide residue by a series of enzymes collectively known as peptidylglycine-alpha-amidating monooxygenase. Concurrently with these processing steps, the N-terminal Gln (glutamine) is converted into pyroglutamate (a cyclic residue). These multiple steps produce 6 copies of the mature TRH molecule per precursor molecule for human TRH (5 for mouse TRH).

TRH synthesizing neurons of the paraventricular nucleus project to the medial portion of the external layer of the median eminence. Following secretion at the median eminence, TRH travels to the anterior pituitary via the hypophyseal portal system where it binds to the TRH receptor stimulating the release of thyroid-stimulating hormone from thyrotropes and prolactin from lactotropes.[4] The half-life of TRH in the blood is approximately 6 minutes.

TRH is also produced in many hypothalamic neurons not associated with the pituitary, as well as multiple other CNS regions (including the spinal cord, brainstem, thalamus, amygdala, and hippocampus), indicating various non-neuroendocrine functions.[1]

TRH is additionally produced in multiple endocrine and non-endocrine tissues outside the CNS, including the anterior pituitary, parafollicular cells of the thyroid glands, medulla of the adrenal gland, islet cells of the pancreas, Leydig cells of the testis, epididymis, prostate, GI tract, spleen, lung, ovary, retina, and hair follicles.[1]

Regulation of release

[edit]Regulation of TRH release is regulated principally by a negative feedback loop by thyroid hormone, and a neuronal open loop by hypothalamic factors. TRH release is additionally regulated by other circulating hormones (including glucocorticoids, and oestrogens), and inhibited by cytokines. The tanycytes of the median eminence also exert a regulatory effect on TRH release.[1]

Function and effects

[edit]Neurotransmission and neuromodulation

[edit]Extensive production of TRH throughout the CNS various non-endocrine (neurotransmissive and neuromodulatory) functions. Indeed, artificial administration into the CNS exhibits autonomic (hyperthermic, hypertensive, positive chronotropic, and gastrokinetic effects, and promotion of insulin and gastric acid release), antiepileptic, anxiolytic, and pro-locomotive effect.[1]

Structure

[edit]TRH is a tripeptide, with an amino acid sequence of pyroglutamyl-histidyl-proline amide.

History

[edit]The structure of TRH was first determined, and the hormone synthesized, by Roger Guillemin and Andrew V. Schally in 1969.[5][6] Both parties insisted their labs determined the sequence first: Schally first suggested the possibility in 1966, but abandoned it after Guillemin proposed TRH was not actually a peptide. Guillemin's chemist began concurring with these results in 1969, as NIH threatened to cut off funding for the project, leading both parties to return to work on synthesis.[7]

Schally and Guillemin shared the 1977 Nobel Prize in Medicine "for their discoveries concerning the peptide hormone production of the brain."[8] News accounts of their work often focused on their "fierce competition" and use of a very large number of sheep and pig brains to locate the hormone.[7]

Clinical significance

[edit]Diagnostic

[edit]Intravenous injection of TRH has been used for diagnostic purposes in the context of the TRH test; administration of exogenous TRH can be used to determine whether hypothyroidism is of hypothalamic or hypophyseal etiology. However, this diagnostic approach has been superseded by ultrasensitive TSH assays and is nowadays only seldom employed.[1]

ACTH and GH release

[edit]TRH promotes release growth hormone (GH) in individuals with certain pathological conditions, and of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) in some individuals with Cushing's disease.[1]

TRH promotes GH release in individuals with acromegaly; prolonged exposure to GHRH may cause the pituitary to release GH in response to TRH. TRH may also promote GH release in individuals with hepatic disease, uremia, childhood hypothyroidism, anorexia nervosa, and depression. Conversely, TRH suppresses GH release during sleep.[1]

Side effects

[edit]Side effects after intravenous TRH administration are minimal.[9] Nausea, flushing, urinary urgency, and mild rise in blood pressure have been reported.[10] After intrathecal administration, shaking, sweating, shivering, restlessness, and mild rise in blood pressure were observed.[11]

Research

[edit]TRH has been evaluated for the treatment of various neurological disorders. It has been attempted for treatment of various epileptic disorders. TRH has been shown to improve outcomes of CNS injuries in experimental models. Efficacy for the treatment ALS and spinal muscle atrophy has not been demonstrated.[1]

Many individuals with depression exhibit a blunted endocrine response to TRH due to unknown reasons, and the response is correlated with clinical outcomes. Involvement of TRH in the pathogenesis of depression has nevertheless not been well established. TRH has undergone research for its ostensible antidepressant properties, however, results regarding efficacy have been inconsistent.[1] One study on a small sample of people with treatment-resistant depression found short-lived anti-depressant and anti-suicidal effects when TRH was administered intrathecally.[11] An orally bioavailable prodrug is being researched.[12] In 2012, the U.S. Army awarded a research grant to develop a TRH nasal spray for suicide prevention amongst veterans.[13][14]

TRH acts as a wakefulness-promoting agent, causing awakening from sleep or sedation.[1]

TRH has been shown to exert anti-aging effect in a mice model.[15]

| Thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | TRH | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF05438 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR008857 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Williams Textbook of Endocrinology (15th ed.). Elsevier. 2024. pp. 109–110. ISBN 9780323933476.

- ^ Urayama A, Yamada S, Kimura R, Zhang J, Watanabe Y (December 2002). "Neuroprotective effect and brain receptor binding of taltirelin, a novel thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH) analogue, in transient forebrain ischemia of C57BL/6J mice". Life Sciences. 72 (4–5): 601–607. doi:10.1016/S0024-3205(02)02268-3. PMID 12467901.

- ^ Taylor T, Wondisford FE, Blaine T, Weintraub BD (January 1990). "The paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus has a major role in thyroid hormone feedback regulation of thyrotropin synthesis and secretion". Endocrinology. 126 (1): 317–324. doi:10.1210/endo-126-1-317. PMID 2104587.

- ^ Bowen R (1998-09-20). "Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone". Pathophysiology of the Endocrine System. Colorado State University. Retrieved 2009-03-04.

- ^ Boler J, Enzmann F, Folkers K, Bowers CY, Schally AV (November 1969). "The identity of chemical and hormonal properties of the thyrotropin releasing hormone and pyroglutamyl-histidyl-proline amide". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 37 (4): 705–710. doi:10.1016/0006-291X(69)90868-7. PMID 4982117.

- ^ Burgus R, Dunn TF, Desiderio D, Guillemin R (November 1969). "[Molecular structure of the hypothalamic hypophysiotropic TRF factor of ovine origin: mass spectrometry demonstration of the PCA-His-Pro-NH2 sequence]". Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences, Série D (in French). 269 (19): 1870–1873. PMID 4983502.

- ^ a b Woolgar S, Latour B (1979). "Chapter 3: The Case of TRF(H)". Laboratory life: the social construction of scientific facts. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. ISBN 0-8039-0993-4.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1977". NobelPrize.org. Retrieved 2009-03-04.

- ^ Prange AJ, Lara PP, Wilson IC, Alltop LB, Breese GR (November 1972). "Effects of thyrotropin-releasing hormone in depression". Lancet. 2 (7785): 999–1002. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(72)92407-5. PMID 4116985. S2CID 40592228.

- ^ Borowski GD, Garofano CD, Rose LI, Levy RA (January 1984). "Blood pressure response to thyrotropin-releasing hormone in euthyroid subjects". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 58 (1): 197–200. doi:10.1210/jcem-58-1-197. PMID 6417153.

- ^ a b Marangell LB, George MS, Callahan AM, Ketter TA, Pazzaglia PJ, L'Herrou TA, et al. (March 1997). "Effects of intrathecal thyrotropin-releasing hormone (protirelin) in refractory depressed patients". Archives of General Psychiatry. 54 (3): 214–222. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830150034007. PMID 9075462.

- ^ Prokai-Tatrai K, De La Cruz DL, Nguyen V, Ross BP, Toth I, Prokai L (July 2019). "Brain Delivery of Thyrotropin-Releasing Hormone via a Novel Prodrug Approach". Pharmaceutics. 11 (7): 349. doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics11070349. PMC 6680701. PMID 31323784.

- ^ "Scientist developing anti-suicide nasal spray". ArmyTimes.com. 25 July 2012. Retrieved 2012-07-05.

- ^ "Army anti-suicide initiative brings $3 million to IU School of Medicine scientist's research". Indiana University School of Medicine. July 24, 2012.

- ^ Pierpaoli W (February 2013). "Aging-reversing properties of thyrotropin-releasing hormone". Current Aging Science. 6 (1): 92–8. doi:10.2174/1874609811306010012. PMID 23895526.

External links

[edit] Media related to Thyrotropin-releasing hormone at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Thyrotropin-releasing hormone at Wikimedia Commons