Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Tuoba

View on Wikipedia| Tuoba | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 拓跋, 拓拔, 托跋, 托拔, 㩉拔 | ||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 拓跋 | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

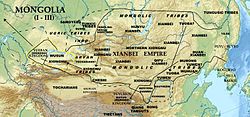

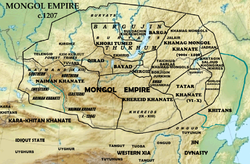

The Tuoba (Chinese) or Tabgatch (Old Turkic: 𐱃𐰉𐰍𐰲, Tabγač), also known by other names, was an influential Xianbei clan in early imperial China. During the Sixteen Kingdoms after the fall of Han and the Three Kingdoms, the Tuoba established and ruled the Dai state in northern China. The dynasty ruled from 310 to 376 and was restored in 386. The same year, the dynasty was renamed Wei, later distinguished in Chinese historiography as the Northern Wei. This powerful state gained control of most of northern China, supporting Buddhism while increasingly sinicizing. As part of this process, in 496, the Emperor Xiaowen changed the imperial clan's surname from Tuoba to Yuan (元). The empire split into Eastern Wei and Western Wei in 535, with the Western Wei's rulers briefly resuming use of the Tuoba name in 554.

A branch of the Tanguts also bore a surname transcribed as Tuoba before their chieftains were given the Chinese surnames Li (李) and Zhao (趙) by the Tang and Song dynasties respectively. Some of these Tangut Tuobas later adopted the surname Weiming (嵬名), with this branch eventually establishing and ruling the Western Xia in northwestern China from 1038 to 1227.

Names

[edit]By the 8th century,[1] the Old Turkic form of the name was Tabγač (𐱃𐰉𐰍𐰲), usually anglicized as Tabgatch[2][3][4] or Tabgach.[5] The name appears in other Central Asian accounts as Tabghāj and Taugash[6] and in Byzantine Greek sources like Theophylact Simocatta's History as Taugas (Ancient Greek: Ταυγάς) and Taugast (Ταυγάστ).[7] Zhang Xushan and others have argued for the name's ultimate derivation from a transcription into Turkic languages of the Chinese name "Great Han"[8] (大漢, s 大汉, Dà Hàn, MC *Dàj Xàn).

Tuoba is the atonal pinyin romanization of the Mandarin pronunciation of the Chinese 拓跋 (Tuòbá), whose pronunciation at the time of its transcription into Middle Chinese has been reconstructed as *tʰak-bɛt[citation needed] or *Thak-bat.[9] The same name also appears with the first character transcribed as 托 or 㩉[10] and with the second character transcribed as 拔;[citation needed] it has also been anglicized as T'o-pa[5] and as Toba.[2][3] The name is also attested as Tufa (禿髮, Tūfà or Tūfǎ),[11] whose Middle Chinese pronunciation has been reconstructed as *tʰuwk-pjot,[citation needed] *T'ak-bwat, or *T'ak-buat.[12] The name is also sometimes clarified as the Tuoba Xianbei (拓跋鮮卑, Tuòbá Xiānbēi).[3][4]

Ethnicity and language

[edit]According to Hyacinth (Bichurin), an early 19th-century scholar, the Tuoba and their Rouran enemies descended from common ancestors.[13] The Rouran state was undoubtedly multi-ethnic. As the ancient sources regard the Rouran as a separate branch of the Xiongnu[14] Book of Song and Book of Liang connected Rourans to the earlier Xiongnu[15][16] while The Weishu stated that the Rourans were of Donghu origins[17][18] and the Tuoba originated from the Xianbei,[19][20] who were also Donghu's descendants.[21][22] The Xianbei were likely not of a single ethnicity, but rather a multilingual, multi-ethnic confederation.[23][24][25][26] The Donghu ancestors of Tuoba and Rouran were most likely proto-Mongols.[27]

Alexander Vovin (2007) identifies the Tuoba language as a Mongolic language.[28][29] On the other hand, Juha Janhunen proposed that the Tuoba might have spoken an Oghur Turkic language.[30] René Grousset, writing in the early 20th century, identifies the Tuoba as a Turkic tribe.[31] According to Peter Boodberg, a 20th-century scholar, the Tuoba language was essentially Turkic with Mongolic admixture.[32] Chen Sanping observed that the Tuoba language contains both elements.[33][34] According to Joo-Yup Lee nomadic confederations were often made up of tribes of diverse linguistic backgrounds. For instance, the ruling elite of the Tuoba Wei dynasty (386–534CE) was made up of both Turkic and Mongolic groups. While migrating southward to northern China from their original abode in northeastern Mongolia, the Para-Mongolic Tuoba assimilated several Turkic Dingling (Tiele) tribes such as the Hegu (Qirghiz) and Yizhan. As a result, the Dingling elements constituted as much as a quarter of the Tuoba tribe. [35] Liu Xueyao stated that the Tuoba may have had their own language which should not be assumed to be identical with any other known languages.[36] Andrew Shimunek (2017) classifies Tuoba (Tabghach) as a "Serbi" (i.e., para-Mongolic) language. Shimunek's Serbi branch also consists of the Tuyuhun and Khitan languages.[37] An-King Lim (2016, 2023) classifies Tuoba (Tabghatch) as Turkic language.[38][39]

History

[edit]

The Tuoba were a Xianbei clan.[2][3] The distribution of the Xianbei people ranged from present day Northeast China to Mongolia, and the Tuoba were one of the largest clans among the western Xianbei, ranging from present day Shanxi province and westward and northwestward. They established the state of Dai from 310 to 376 AD[40] and ruled as the Northern Wei from 386 to 536. The Tuoba states of Dai and Northern Wei also claimed to possess the quality of earth in the Chinese Wu Xing theory. All the chieftains of the Tuoba were revered as emperors in the Book of Wei and the History of the Northern Dynasties. A branch of the Tuoba in the west known as the Tufa also ruled the Southern Liang dynasty from 397 to 414 during the Sixteen Kingdoms period.

The Northern Wei started to arrange for Chinese elites to marry daughters of the Xianbei Tuoba royal family in the 480s.[41] More than fifty percent of Tuoba Xianbei princesses of the Northern Wei were married to southern Chinese men from the imperial families and aristocrats from southern China of the Southern dynasties who defected and moved north to join the Northern Wei.[42] Some Chinese exiled royalty fled from southern China and defected to the Xianbei. Several daughters of the Xianbei Tuoba Emperor Xiaowen of Northern Wei were married to Chinese elites: the Han Chinese Liu Song royal Liu Hui married Princess Lanling of the Northern Wei;[43][44][45][46][43][47][48] Princess Huayang married Sima Fei, a descendant of Jin dynasty (266–420) royalty; Princess Jinan married Lu Daoqian; and Princess Nanyang married Xiao Baoyin (萧宝夤), a member of Southern Qi royalty.[49] Emperor Xiaozhuang of Northern Wei's sister the Shouyang Princess was wedded to Emperor Wu of Liang's son Xiao Zong.[50] One of Emperor Xiaowu of Northern Wei's sisters was married to Zhang Huan, a Han Chinese, according to the Book of Zhou. His name is given as Zhang Xin in the Book of Northern Qi and History of the Northern Dynasties which mention his marriage to a Xianbei princess of Wei. His personal name was changed due to a naming taboo on the emperor's name. He was the son of Zhang Qiong.[51]

When the Eastern Jin dynasty ended, Northern Wei received the Han Chinese Jin prince Sima Chuzhi as a refugee. A Northern Wei Princess married Sima Chuzhi, giving birth to Sima Jinlong (司馬金龍). Northern Liang Xiongnu King Juqu Mujian's daughter married Sima Jinlong.[52]

Genetics

[edit]According to Zhou (2006) the haplogroup frequencies of the Tuoba Xianbei were 43.75% haplogroup D, 31.25% haplogroup C, 12.5% haplogroup B, 6.25% haplogroup A and 6.25% "other."[53]

Zhou (2014) obtained mitochondrial DNA analysis from 17 Tuoba Xianbei, which indicated that these specimens were, similarly, completely East Asian in their maternal origins, belonging to haplogroups D, C, B, A and haplogroup G.[54]

Chieftains of Tuoba Clan 219–376 (as Princes of Dai 315–376)

[edit]| Posthumous name | Full name | Period of reign | Other |

|---|---|---|---|

| 神元 Shényuán | 拓拔力微 Tuòbá Lìwéi | 219–277 | Temple name: 始祖 Shízǔ |

| 章 Zhāng | 拓拔悉鹿 Tuòbá Xīlù | 277–286 | |

| 平 Píng | 拓拔綽 Tuòbá Chuò | 286–293 | |

| 思 Sī | 拓拔弗 Tuòbá Fú | 293–294 | |

| 昭 Zhāo | 拓拔祿官 Tuòbá Lùguān | 294–307 | |

| 桓 Huán | 拓拔猗㐌 Tuòbá Yītuō | 295–305 | |

| 穆 Mù | 拓拔猗盧 Tuòbá Yīlú | 295–316 | |

| None | 拓拔普根 Tuòbá Pǔgēn | 316 | |

| None | 拓拔 Tuòbá[55] | 316 | |

| 平文 Píngwén | 拓跋鬱律 Tuòbá Yùlǜ | 316–321 | |

| 惠 Huì | 拓拔賀傉 Tuòbá Hèrǔ | 321–325 | |

| 煬 Yáng | 拓拔紇那 Tuòbá Hénǎ | 325–329 and 335–337 | |

| 烈 Liè | 拓拔翳槐 Tuòbá Yìhuaí | 329–335 and 337–338 | |

| 昭成 Zhaōchéng | 拓拔什翼健 Tuòbá Shíyìqiàn | 338–376 | Regnal name: 建國 Jiànguó |

Legacy

[edit]

As a consequence of the Northern Wei's extensive contacts with Central Asia, Turkic sources identified Tabgach, also transcribed as Tawjach, Tawġač, Tamghaj, Tamghach, Tafgaj, and Tabghaj, as the ruler or country of China until the 13th century.[56]

The Orkhon inscriptions in the Orkhon Valley in modern-day Mongolia from the 8th century identify Tabgach as China.[56]

I myself, wise Tonyukuk, lived in Tabgach country. (As the whole) Turkic people was under Tabgach subjection.[57]

In the 11th century text, the Dīwān Lughāt al-Turk ("Compendium of the languages of the Turks"), Turkic scholar Mahmud al-Kashgari, writing in Baghdad for an Arabic audience, describes Tawjach as one of the three components comprising China.

Ṣīn [i.e., China] is originally three fold: Upper, in the east which is called Tawjāch; middle which is Khitāy, lower which is Barkhān in the vicinity of Kashgar. But now Tawjāch is known as Maṣīn and Khitai as Ṣīn.[56]

At the time of his writing, China's northern fringe was ruled by Khitan-led Liao dynasty while the remainder of China proper was ruled by the Northern Song dynasty. Arab sources used Sīn to refer to northern China and Māsīn to represent southern China.[56] In his account, al-Kashgari refers to his homeland, around Kashgar, then part of the Kara-Khanid Khanate, as Lower China.[56] The rulers of the Karakanids adopted Tamghaj Khan (Turkic: the Khan of China) in their title, and minted coins bearing this title.[58] Much of the realm of the Karakhanids including Transoxania and the western Tarim Basin had been under the rule of the Tang dynasty prior to the Battle of Talas in 751, and the Karakhanids continued to identify with China, several centuries later.[58]

The Tabgatch name for the political entity has also been translated into Chinese as Taohuashi (Chinese: 桃花石; pinyin: táohuā shí).[59] This name has been used in China in recent years to promote ethnic unity.[60][61]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Zhang (2010), p. 496.

- ^ a b c Grousset, Rene (1970). The Empire of the Steppes. Rutgers University Press. pp. 60–65. ISBN 0-8135-1304-9.

- ^ a b c d Holcombe, Charles (2001). The Genesis of East Asia: 221 B.C. - A.D. 907. p. 131. ISBN 978-0-8248-2465-5.

- ^ a b Brindley (2003), p. 1.

- ^ a b Sinor (1990), p. 288.

- ^ Zhang (2010), p. 496–497.

- ^ Zhang (2010), p. 485.

- ^ Zhang (2010), pp. 491, 493, 495.

- ^ Zhang (2010), p. 488.

- ^ "资治通鉴大辞典·上编".

㩉拔氏:(...) 鲜卑氏族之一。即"托跋氏"

- ^ Wang Penglin (2018), Linguistic Mysteries of Ethnonyms in Inner Asia, Lexington Books, p. 135, ISBN 978-1-4985-3528-1.

- ^ Zhang (2010), p. 489.

- ^ Hyacinth (Bichurin) (1950). Collection of information on peoples lived in Central Asia in ancient times. p. 209.

- ^ Litvinsky (2006). History of Civilizations of Central Asia The crossroads of civilizations: A.D. 250 to 750. p. 317.

- ^ Songshu vol. 95 Archived 2020-06-06 at the Wayback Machine. "芮芮一號大檀,又號檀檀,亦匈奴別種。" tr. "Ruìruì, one appellation is Dàtán, also called Tántán; they were also a separate stock of the Xiōngnú."

- ^ Liangshu vol. 54 Archived 2018-11-22 at the Wayback Machine. quote: "芮芮國,蓋匈奴別種。" translation: "The Ruìruì nation, possibly a separate stock of the Xiōngnú."

- ^ Golden, B. Peter (2013). "Some Notes on the Avars and Rouran". In Curta, Florin; Maelon, Bogdan-Petru (eds.). The Steppe Lands and the World beyond Them. Iaşi. p. 55.

- ^ Book of Wei. Vol. 103.

蠕蠕,東胡之苗裔也,姓郁久閭氏

[Rúrú, offspring of Dōnghú, surnamed Yùjiŭlǘ] - ^ Wei Shou. Book of Wei. Vol. 1

- ^ Tseng, Chin Yin (2012). The Making of the Tuoba Northern Wei: Constructing Material Cultural Expressions in the Northern Wei Pingcheng Period (398–494 CE) (PhD). University of Oxford. p. 1.

- ^ . Vol. 90.

鮮卑者,亦東胡之支也,別依鮮卑山,故因號焉

[The Xianbei who were a branch of the Donghu, relied upon the Xianbei Mountains. Therefore, they were called the Xianbei.] - ^ Xu Elina-Qian (2005). Historical Development of the Pre-Dynastic Khitan. University of Helsinki.

- ^ Golden 2013, p. 47, quote: "The Xianbei confederation appears to have contained speakers of Pre-Proto-Mongolic, perhaps the largest constituent linguistic group, as well as former Xiongnu subjects, who spoke other languages, Turkic almost certainly being one of them."

- ^ Pulleyblank, Edwin G. (1983). "The Chinese and Their Neighbors in Prehistoric and Early Historic China," in The Origins of Chinese Civilization, University of California Press, p. 452 of pp. 411–466.

- ^ Kradin N. N. (2011). "Heterarchy and hierarchy among the ancient Mongolian nomads". Social Evolution & History. 10 (1): 188.

- ^ Janhunen 2006, pp. 405–6.

- ^ Pulleyblank, Edwin G. (2000). "Ji 姬 and Jiang 姜: The Role of Exogamic Clans in the Organization of the Zhou Polity" (PDF). Early China. p. 20. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-11-18.

- ^ Vovin, Alexander (2007). "Once again on the Tabγač language". Mongolian Studies. XXIX: 191–206.

- ^ Holcombe (2001). The Genesis of East Asia. p. 132. ISBN 978-0-8248-2465-5.

- ^ Juha Janhunen (1996). Manchuria: An Ethnic History. p. 190.

- ^ Steppes, Empire (1939). Turkic vigor-so marked among the first Tabgatch ruler. United States: René Grousset. ISBN 978-0-8135-0627-2.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Holcombe (2001). The Genesis of East Asia. p. 132. ISBN 978-0-8248-2465-5.

- ^ Chen, Sanping (2005). "Turkic or Proto-Mongolian? A Note on the Tuoba Language". Central Asiatic Journal. 49 (2): 161–73.

- ^ Holcombe (2001). The Genesis of East Asia. p. 248. ISBN 978-0-8248-2465-5.

- ^ Lee, Joo-Yup (2016). "The Historical Meaning of the Term Turk and the Nature of the Turkic Identity of the Chinggisid and Timurid Elites in Post-Mongol Central Asia". Central Asiatic Journal. 59 (1–2): 113–4.

- ^ Liu 2012, pp. 83–86.

- ^ Shimunek, Andrew (2017). Languages of Ancient Southern Mongolia and North China: a Historical-Comparative Study of the Serbi or Xianbei Branch of the Serbi-Mongolic Language Family, with an Analysis of Northeastern Frontier Chinese and Old Tibetan Phonology. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3-447-10855-3. OCLC 993110372.

- ^ An-King Lim (2016). "On Sino-Turkic, a First Glance (北俗初探)". Journal of Language Contact.

- ^ An-King Lim (2023). "On the 5 th -century Tabghatch Sinification A pivotal event in Sinitic historical phonology 拓跋氏漢化及切韻"

- ^ Grousset, Rene (1970). The Empire of the Steppes. Rutgers University Press. pp. 57. ISBN 0-8135-1304-9.

- ^ Rubie Sharon Watson (1991). Marriage and Inequality in Chinese Society. University of California Press. pp. 80–. ISBN 978-0-520-07124-7.

- ^ Tang, Qiaomei (May 2016). Divorce and the Divorced Woman in Early Medieval China (First through Sixth Century) (PDF) (A dissertation presented by Qiaomei Tang to The Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of East Asian Languages and Civilizations). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University. pp. 151, 152, 153.

- ^ a b Lee 2014.

- ^ Papers on Far Eastern History. Australian National University, Department of Far Eastern History. 1983. p. 86.

- ^ Hinsch, Bret (2018). Women in Early Medieval China. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 97. ISBN 978-1-5381-1797-2.

- ^ Hinsch, Bret (2016). Women in Imperial China. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 72. ISBN 978-1-4422-7166-1.

- ^ Papers on Far Eastern History, Volumes 27–30. Australian National University, Department of Far Eastern History. 1983. pp. 86, 87, 88.

- ^ Wang, Yi-t'ung (1953). "Slaves and Other Comparable Social Groups During The Northern Dynasties (386-618)". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. 16 (3/4). Harvard-Yenching Institute: 322. doi:10.2307/2718246. JSTOR 2718246.

- ^ China: Dawn of a Golden Age, 200–750 AD. Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2004. pp. 30–. ISBN 978-1-58839-126-1.

Xiao Baoyin.

- ^ Ancient and Early Medieval Chinese Literature (vol. 3 & 4): A Reference Guide, Part Three & Four. BRILL. 22 September 2014. pp. 1566–. ISBN 978-90-04-27185-2.

- ^ Adamek, Piotr (2017). Good Son is Sad If He Hears the Name of His Father: The Tabooing of Names in China as a Way of Implementing Social Values. Routledge. p. 242. ISBN 978-1-351-56521-9.

... Southern Song.105 We read the story of a certain Zhang Huan 張歡 in the Zhoushu, who married a sister of Emperor Xiaowu 宣武帝 of the Northern Wei (r.

- ^ China: Dawn of a Golden Age, 200–750 AD. Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2004. pp. 18–. ISBN 978-1-58839-126-1.

sima.

- ^ Zhou, Hui (20 October 2006). "Genetic analysis on Tuoba Xianbei remains excavated from Qilang Mountain Cemetery in Qahar Right Wing Middle Banner of Inner Mongolia". FEBS Letters. 580 (26): Table 2. doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2006.10.030. PMID 17070809. S2CID 19492267.

- ^ Zhou, Hui (March 2014). "Genetic analyses of Xianbei populations about 1,500–1,800 years old". Human Genetics. 50 (3): 308–314. doi:10.1134/S1022795414030119. S2CID 18809679.

- ^ No known given name survives.

- ^ a b c d e Biran 2005, p. 98.

- ^ Atalay Besim (2006). Divanü Lügati't Türk. Turkish Language Association, ISBN 975-16-0405-2, p. 28, 453, 454

- ^ a b Biran, Michal (2001). "Qarakhanid Studies: A View from the Qara Khitai Edge". Cahiers d'Asie centrale. 9: 77–89.

- ^ Rui, Chuanming (2021). On the Ancient History of the Silk Road. World Scientific. doi:10.1142/9789811232978_0005. ISBN 978-981-12-3296-1.

- ^ Victor Mair (May 16, 2022). "Tuoba and Xianbei: Turkic and Mongolic elements of the medieval and contemporary Sinitic states". Language Log. Retrieved 5 April 2024.

- ^ 习近平 (2019-09-27). "在全国民族团结进步表彰大会上的讲话". National Ethnic Affairs Commission of the People's Republic of China (in Chinese). Retrieved 5 April 2024.

分立如南北朝,都自诩中华正统;对峙如宋辽夏金,都被称为"桃花石";统一如秦汉、隋唐、元明清,更是"六合同风,九州共贯"。

Sources

[edit]- Bazin, L. "Research of T'o-pa language (5th century AD)", T'oung Pao, 39/4-5, 1950 ["Recherches sur les parlers T'o-pa (5e siècle après J.C.)"] (in French) Subject: Toba Tatar language

- Biran, Michal (2005), The Empire of the Qara Khitai in Eurasian History: Between China and the Islamic World, Cambridge University Press

- Boodberg, P.A. "The Language of the T'o-pa Wei", Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies, Vol. 1, 1936.

- Brindley, Erica Fox (2003), "Barbarians or Not? Ethnicity and Changing Conceptions of the Ancient Yue (Viet) Peoples, ca. 400–50 BC" (PDF), Asia Major, 3rd Series, 16 (2): 1–32, JSTOR 41649870.

- Clauson, G. "Turk, Mongol, Tungus", Asia Major, New Series, Vol. 8, Pt 1, 1960, pp. 117–118

- Grousset, R. "The Empire of the Steppes: A History of Central Asia", Rutgers University Press, 1970, p. 57, 63–66, 557 Note 137, ISBN 0-8135-0627-1 [1]

- Lee, Jen-der (2014). "9. Crime and Punishment: The Case of Liu Hui in the Wei Shu". In Wendy Swartz; et al. (eds.). Early Medieval China: A Sourcebook. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 156–165. ISBN 978-0-231-15987-6.

- Liu, Xueyao (2012). 鮮卑列國:大興安嶺傳奇. ISBN 978-962-8904-32-7.

- Pelliot, P.A. "L'Origine de T'ou-kiue; nom chinoise des Turks", T'oung Pao, 1915, p. 689

- Pelliot, P.A. "L'Origine de T'ou-kiue; nom chinoise des Turks", Journal Asiatic, 1925, No 1, p. 254-255

- Pelliot, P.A. "L'Origine de T'ou-kiue; nom chinoise des Turks", T'oung Pao, 1925–1926, pp. 79–93;

- Sinor, Denis (1990), "The Establishment and Dissolution of the Türk Empire", The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 285–316.

- Zhang Xushan (2010), "On the Origin of 'Taugast' in Theophylact Simocatta and the Later Sources", Byzantion, vol. 80, Leuven: Peeters, pp. 485–501, JSTOR 44173113.

- Zuev, Y.A. "Ethnic History Of Usuns", Works of Academy of Sciences Kazakh SSR, History, Archeology And Ethnography Institute, Alma-Ata, Vol. VIII, 1960, (In Russian)

Tuoba

View on GrokipediaNomenclature

Etymology and Variants

The name Tuoba (Chinese: 拓跋; pinyin: Tuòbá; Middle Chinese: *tʰak-bɛt) represents the Han Chinese phonetic transcription of the clan's original designation in their native tongue, a language associated with the Xianbei and debated among linguists as containing Proto-Mongolic elements with possible Turkic admixtures.[3][9] Chinese historical records first attest the name in the context of the clan's chieftains from the 3rd century CE, with variant spellings including 拓拔 (Tuòbá), 托跋 (Tuóbá), and 托拔 (Tuóbá), reflecting regional or scribal differences in transcription during the Wei-Jin period. In Old Turkic sources, such as the 8th-century Orkhon inscriptions, the name appears as Tabγač (transliterated as Tabgach or Taugast), a metathesized form (*t'akbat > tabγač) that later extended to denote China (Tabgach as a toponym for Tang territories), likely due to the Tuoba clan's establishment of the Northern Wei dynasty (386–535 CE) and its cultural dominance in northern Eurasia.[10] Scholarly interpretations of the etymology remain tentative, with one analysis proposing that Tuoba derives from a descriptive term meaning "arranging in tresses," possibly alluding to nomadic hairstyling practices among steppe peoples.[11] This aligns with broader Xianbei onomastic patterns but lacks direct attestation in surviving Tuoba-language texts, underscoring the challenges of reconstructing non-Chinese steppe ethnonyms from secondary transcriptions.Ethnic and Linguistic Identity

Debates on Affiliation

The Tuoba are conventionally classified as a prominent clan within the Xianbei tribal confederation, which emerged from the Donghu peoples of the eastern Eurasian steppes around the 1st century BCE and expanded southward into northern China by the 4th century CE.[12] This affiliation positions them among proto-Mongolic nomadic groups, with the Xianbei often linked to early Mongolic linguistic and cultural substrates, as evidenced by toponyms like the Greater Khingan Mountains (associated with Xianbei presence) and phonetic reconstructions such as *serbi for Xianbei, paralleling Mongolic roots like Khalkha seren.[3] Historical records, including the Weishu, trace Tuoba origins to Xianbei lineages, emphasizing their role in unifying tribes under chieftains like Tuoba Gui, who founded the Northern Wei in 386 CE.[13] Linguistic debates, however, challenge a purely proto-Mongolic characterization, highlighting potential Turkic substrates or admixtures within Tuoba speech. Peter Boodberg proposed that the Tuoba language was predominantly Turkic with Mongolic elements, citing lexical and phonological parallels in preserved names and titles.[3] Juha Janhunen similarly classified it as Oghur Turkic, while René Grousset viewed the Tuoba as a Turkic tribe outright.[3] In contrast, Alexander Vovin (2007) argued for a Mongolic affiliation, analyzing Xianbei-derived terms like qifen ("grass") as reflecting Mongolic etymologies, such as those evolving into Yuwen clan nomenclature.[3] Chen Sanping noted hybrid features, attributing Turkic influences to the Tuoba confederation's incorporation of approximately 25% Dingling (proto-Turkic) elements alongside core Xianbei groups.[3] These disputes stem from sparse direct evidence—primarily reconstructed names like tʰak-bɛt for Tuoba and references in Old Turkic Orkhon inscriptions, where "Tabgach" denotes the Tuoba/Wei realm but may reflect exonyms rather than native self-designation.[3] No consensus exists, with interpretations varying by methodological emphasis: phonetic correspondences favor Mongolic for broader Xianbei identity, while onomastic and confederative diversity support Turkic layers.[3] Such debates underscore the fluid ethnic boundaries of steppe confederations, where multilingualism and alliances blurred genetic linguistic affiliations prior to Northern Wei sinicization edicts in 496 CE, which suppressed non-Han nomenclature.[13]Language Evidence

The linguistic record of the Tuoba is sparse, comprising primarily Chinese transcriptions of personal names, clan designations, toponyms, and occasional terms or titles documented in dynastic histories such as the Weishu (compiled circa 554 CE), with no surviving native texts or inscriptions providing direct grammatical or lexical corpus. This onomastic evidence, drawn from records of Tuoba chieftains and tribes active between the 3rd and 5th centuries CE, reveals non-Sinitic phonetic patterns and morphological features inconsistent with Old Chinese but showing affinities to Altaic structures. Scholars like Lajos Ligeti, based on comparative phonology of these names, classified the Tuoba dialect as proto-Mongolic, part of the broader Xianbei linguistic conglomerate.[14] Comparative linguistics supports affiliation with para-Mongolic or Serbi-Mongolic languages, a hypothetical branch ancestral to but distinct from Classical Mongolian, evidenced by reconstructed forms from Tuoba names exhibiting vowel harmony, consonant clusters, and suffixes paralleling Mongolic patterns—such as potential cognates for fauna and celestial terms. For example, the Tuoba term Foli (transcribed for the personal name of Tuoba Gui, r. 386–409 CE) has been interpreted as denoting "wolf," aligning with proto-Mongolic möngke or related roots for predatory animals, a motif recurrent in steppe ethnonyms. Similarly, tribal names like Pulan (a Tuoba subgroup) appear as variants of Mulan, possibly reflecting para-Mongolic etymons for tribal identities, while Chinu (linked to "wolf" or clan totems) and Youlian (evoking "cloud" or atmospheric phenomena) suggest semantic fields common in Mongolic vocabularies for nature and kinship.[15][9] Debate persists over Turkic versus Mongolic dominance, with some analyses, such as those by Chen Sanping, identifying admixtures—e.g., Turkic-like loanwords in later Tuoba nomenclature possibly from interactions with emerging Göktürk groups post-5th century—but the core lexicon and phonological inventory favor proto-Mongolian substrates, as the Xianbei complex predates widespread Turkic expansion in the region. Andrew Shimunek's reconstructions of Serbi-Mongolic forms from Xianbei toponyms in northern China and Mongolia further bolster this, positing genetic links to Khitan and other extinct para-Mongolic idioms without requiring Turkic primacy. The scarcity of material limits definitive sound laws, yet the consensus among specialists privileges para-Mongolic classification over alternatives like Tungusic or isolated isolates, informed by substrate influences in Middle Mongolian dialects.[3][16]Genetic Profile

Ancient DNA Studies

A 2006 study examined mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) hypervariable segment I sequences from 16 Tuoba Xianbei remains excavated from the Qilang Mountain cemetery in Qahar Right Wing Middle Banner, Inner Mongolia, associated with the Northern Wei period (386–535 CE). The analysis revealed haplogroups prevalent among northern East Asian populations and indicated a close genetic affinity to modern groups such as the Oroqen, Outer Mongolians, and Evenki, with the strongest similarity to the Oroqen, pointing to origins in the northern steppe regions rather than southern or Central Asian sources.[17] Building on this, a 2014 genetic analysis of mtDNA from multiple Xianbei populations dating 1500–1800 years old, including Tuoba samples, affirmed that Tuoba Xianbei exhibited the closest affinity to the Qilang Mountain Tuoba group. The study highlighted significant differentiation between Tuoba Xianbei and other Xianbei subgroups, such as Murong Xianbei, underscoring subgroup-specific genetic profiles within the broader Xianbei confederation despite shared nomadic heritage.[18] A 2025 study analyzed complete mtDNA genomes from 145 individuals buried in three cemeteries at Pingcheng (modern Datong), the Tuoba-established capital of Northern Wei from 386–494 CE. The results showed substantial maternal genetic similarity and homogeneity between Pingcheng inhabitants and reference Tuoba Xianbei profiles, such as those from Qilang Mountain, confirming the Tuoba's dominant foundational role in the capital's population genetics during the dynasty's early phase. Haplogroup distributions also evidenced integration of maternal lineages from surrounding local groups, including Han Chinese, reflecting limited but detectable admixture as the Tuoba society expanded and administered conquered territories.[19] These mtDNA-focused investigations consistently link Tuoba genetics to northern East Asian steppe nomads, with affinities to proto-Mongolic or Tungusic-speaking populations, though the absence of published nuclear genome data as of October 2025 restricts comprehensive assessment of paternal contributions, autosomal admixture, or Y-chromosome haplogroups.[17][18][19]Population Affinities

Mitochondrial DNA analysis of Tuoba Xianbei remains from the Qilang Mountain cemetery in Inner Mongolia, dating to approximately 1,500–1,800 years ago, reveals a predominance of East Asian haplogroups, with 43.75% belonging to haplogroup D and 31.25% to haplogroup C, alongside smaller frequencies of B (12.5%), A (6.25%), and others.[17] These profiles indicate a strong genetic continuity with northern nomadic populations, exhibiting the closest affinities to modern Tungusic-speaking groups like the Oroqen and Ewenki, as well as Outer Mongolians.[20] Comparative studies further highlight differentiation from other Xianbei subgroups, such as the Murong Xianbei, while suggesting gene flow with Xiongnu populations, evidenced by shared haplotype distributions that imply historical admixture in northern China.[18] Autosomal and uniparental markers from Tuoba-linked sites underscore their foundational role in the genetic makeup of the Northern Wei capital at Pingcheng, where ancient residents displayed substantial maternal homogeneity and similarity to Tuoba Xianbei, reflecting population integration without significant dilution from local Han Chinese lineages during early dynasty phases.[21] This affinity extends to contributions in the maternal gene pools of contemporary northern Asian minorities, potentially through admixture with Xiongnu-derived elements and persistence of steppe nomadic ancestries.[22] Overall, these findings position the Tuoba as genetically aligned with proto-Mongolic and Tungusic clusters rather than southern East Asian or Indo-European groups, consistent with their origins in the eastern Eurasian steppes.[23]Early History

Chieftains from 219–376

The Tuoba clan, part of the Xianbei nomadic confederation in the northern steppes, traces its recorded leadership to Tuoba Liwei, who assumed chieftainship around 219 CE and ruled until approximately 277 CE. Liwei is described in historical annals as unifying eight core Tuoba tribes along with dozens of allied groups, commanding an estimated force of 200,000 warriors, and establishing a political center at Shengle near the Yin Mountains in modern Inner Mongolia. His leadership marked the clan's shift from loose tribal affiliations to a more cohesive entity, engaging in raids and alliances with the weakening Cao Wei state during the Three Kingdoms period.[13] Following Liwei's death, succession disputes and short reigns characterized the early chieftains, reflecting the volatile nomadic politics of the era. Tuoba Shamohan briefly led before his death in 277 CE, after which Tuoba Xilu (r. 277–286 CE) and Tuoba Chuo (r. 286–293 CE) maintained the clan's territorial holdings amid conflicts with neighboring tribes and occasional tribute relations with the Jin dynasty. These leaders focused on consolidating control over grazing lands and livestock-based economy, with limited recorded expansions until the late 3rd century.[24]| Chieftain | Approximate Reign | Key Events and Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Tuoba Liwei | c. 219–277 CE | Unified tribes; base at Shengle; allied with Cao Wei. |

| Tuoba Shamohan | c. 277 CE | Brief rule; died same year. |

| Tuoba Xilu | 277–286 CE | Maintained steppe holdings; died 286 CE. |

| Tuoba Chuo | 286–293 CE | Continued consolidation; died 293 CE. |

| Tuoba Fu | 293–294 CE | Short interregnum; died 294 CE. |

| Tuoba Luguan | 294–307 CE | Expanded influence; died 307 CE. |

| Tuoba Yituo | 295–305 CE | Overlapped reigns indicate co-leadership; died 305 CE. |

| Tuoba Yilu | 295–316 CE | Received Jin titles; established Dai principality in 315 CE as Prince of Dai; controlled Daijun region. |