Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Datong

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

| Datong | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | 大同 | ||||||||

| Literal meaning | Great Unity Great Togetherness | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Former names | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pingcheng | |||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 平城縣 | ||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 平城县 | ||||||||

| Literal meaning | Peaceful City County Pacified City County | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Xijing | |||||||||

| Chinese | 西京 | ||||||||

| Literal meaning | Western Capital | ||||||||

| |||||||||

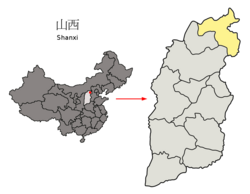

Datong is a prefecture-level city in northern Shanxi Province in the People's Republic of China. It is located in the Datong Basin at an elevation of 1,040 metres (3,410 ft) and borders Inner Mongolia to the north and west and Hebei to the east. As of the 2020 census, it had a population of 3,105,591 of whom 1,790,452 lived in the built-up (or metro) area made of the 2 out 4 urban districts of Pingcheng and Yungang as Yunzhou and Xinrong are not conurbated yet.

History

[edit]

The area of present-day Datong was close to the state of Dai, which was conquered by the Zhao clan of Jin in 457 BC. It was a frontier land between the agricultural Chinese and the nomads of the Great Steppe. The area was well known for its trade in horses.

The area of present-day Datong eventually came under the control of the Qin dynasty, during which it was known as Pingcheng County (平城县) and formed part of the Qin commandery of Yanmen.[4] Pingcheng County continued under the Han dynasty, which founded a site within present-day Datong in 200 BC following its victory against the Xiongnu nomads at the Battle of Baideng. Located near a pass to Inner Mongolia along the Great Wall, Pingcheng blossomed under Han rule and became a stop-off point for camel caravans moving from China into Mongolia and beyond. It was sacked at the end of the Eastern Han. Pingcheng became the capital of the Xianbei-founded Northern Wei dynasty from AD 398–494. The Yungang Grottoes were constructed during the later part of this period (460–494). During the mid to late 520s, Pingcheng was the seat of Northern Wei's Dai Commandery.[5] During the Tang dynasty, Datong became the seat of the Tang prefecture of Yunzhou, and the original Guandi temple was built.[6][7]

The city was renamed Datong in 1048. It was the Xijing ("Western Capital") of the Jurchen Jin dynasty prior to being sacked by the Mongols. Datong later came under the control of the Ming dynasty, serving as an important Ming military stronghold against the Mongols to the north.[7] During the Ming period, many of Datong's notable historical structures such as the Drum Tower and the Nine-Dragon Wall were built.[8][9] Datong was sacked again at the end of the Ming in 1649, but promptly rebuilt in 1652.

By 1982 a portion of its city walls remained so it became one of the National Famous Historical and Cultural Cities that year. Prior to 2008, about 100,000 people lived in the old city. In 2008 mayor Geng Yanbo decided to redevelop much of the inner city, with over 3 square kilometres (1.2 sq mi) being redeveloped, and with Geng becoming known as the "Demolition Mayor". Geng and his group anticipated that 30,000 to 50,000 people would remain in the old city.

In 2013 Geng left his position. Su Jiede of Sixth Tone wrote that much of the city was still under construction at the time and that Geng's efforts resulted in "a half-finished city center and a complicated legacy" and that "To critics, the city had spent enormous sums of money without much to show for it."[10] By 2020 the population of the old city was below 30,000 and there were fewer governmental facilities available for the residents. That year Su stated that the old city "still presents a headache for the local government."[10]

Demographics

[edit]Su Jiede wrote that since Pingcheng District, which had most of its urbanized area, had 1,105,699 people as of 2020, "Datong is a small city by Chinese standards".[10]

Geography

[edit]

Datong is the northernmost city of Shanxi, and is located in the Datong Basin, with an administrative area spanning latitude 39° 03'–40° 44' N and longitude 112° 34'–114° 33' E. The urban area is surrounded on three sides by mountains, with passes only to the east and southwest. Within the prefecture-level city elevations generally increase from southeast to northwest. Datong borders Ulanqab (Inner Mongolia) to the northwest and Zhangjiakou (Hebei) to the east, Shuozhou (Shanxi) to the southwest, and Xinzhou (Shanxi) to the south.

The well-known Datong Volcanic Arc lies nearby in the Datong Basin.

It is 250 kilometres (160 mi) west of Beijing.[10]

Climate

[edit]Datong has a continental, monsoon-influenced steppe climate (Köppen BSk), influenced by the 1,000 metres (3,300 ft)+ elevation, with rather long, cold, very dry winters, and very warm summers. Monthly mean temperatures range from −10.5 °C (13.1 °F) in January to 22.6 °C (72.7 °F) in July; the annual mean temperature is 7.33 °C (45.2 °F). Due to the aridity and elevation, diurnal temperature variation is often large, averaging 13.2 °C (23.8 °F) annually. There barely is any precipitation during winter, and more than 3⁄4 of the annual precipitation occurs from June to September. With monthly percent possible sunshine ranging from 54% in July to 66% in October, sunshine is abundant year-round, and the city receives 2,671 hours (about 60% of the possible total) of bright sunshine per year. Extremes since 1951 have ranged from −31.9 °C (−25 °F) on 16 December 2023 to 39.2 °C (103 °F) on 29 July 2010.

| Climate data for Datong, elevation 1,053 m (3,455 ft), (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1951–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 11.2 (52.2) |

19.2 (66.6) |

25.3 (77.5) |

35.4 (95.7) |

36.1 (97.0) |

39.0 (102.2) |

39.2 (102.6) |

35.9 (96.6) |

34.7 (94.5) |

29.7 (85.5) |

21.9 (71.4) |

15.8 (60.4) |

39.2 (102.6) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | −2.9 (26.8) |

2.1 (35.8) |

9.2 (48.6) |

17.4 (63.3) |

23.7 (74.7) |

27.8 (82.0) |

28.9 (84.0) |

27.2 (81.0) |

22.4 (72.3) |

15.3 (59.5) |

6.2 (43.2) |

−1.3 (29.7) |

14.7 (58.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −10.5 (13.1) |

−5.8 (21.6) |

1.5 (34.7) |

9.7 (49.5) |

16.5 (61.7) |

21.0 (69.8) |

22.7 (72.9) |

20.8 (69.4) |

15.2 (59.4) |

7.7 (45.9) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

−8.4 (16.9) |

7.5 (45.4) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −16.6 (2.1) |

−12.4 (9.7) |

−5.4 (22.3) |

2.1 (35.8) |

8.7 (47.7) |

14.0 (57.2) |

16.7 (62.1) |

14.9 (58.8) |

8.8 (47.8) |

1.4 (34.5) |

−6.8 (19.8) |

−14.1 (6.6) |

0.9 (33.7) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −31.1 (−24.0) |

−29.9 (−21.8) |

−20.9 (−5.6) |

−16.1 (3.0) |

−5.8 (21.6) |

2.9 (37.2) |

7.8 (46.0) |

2.8 (37.0) |

−3.7 (25.3) |

−11.5 (11.3) |

−24.2 (−11.6) |

−31.9 (−25.4) |

−31.9 (−25.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 2.1 (0.08) |

3.6 (0.14) |

8.9 (0.35) |

21.0 (0.83) |

32.8 (1.29) |

53.1 (2.09) |

96.9 (3.81) |

76.1 (3.00) |

60.2 (2.37) |

23.3 (0.92) |

8.3 (0.33) |

1.8 (0.07) |

388.1 (15.28) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 1.8 | 2.2 | 3.6 | 4.3 | 6.6 | 11.2 | 12.5 | 11.1 | 8.8 | 5.5 | 3.1 | 1.7 | 72.4 |

| Average snowy days | 3.3 | 3.9 | 3.8 | 1.7 | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 3.4 | 3.2 | 20.2 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 53 | 46 | 42 | 38 | 40 | 50 | 64 | 68 | 64 | 57 | 54 | 52 | 52 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 192.0 | 200.7 | 236.7 | 255.0 | 278.4 | 256.6 | 249.6 | 243.8 | 225.1 | 225.9 | 189.0 | 182.2 | 2,735 |

| Percentage possible sunshine | 64 | 66 | 64 | 64 | 62 | 57 | 55 | 58 | 61 | 66 | 64 | 63 | 62 |

| Source: China Meteorological Administration[11][12][13] all-time extreme temperature[14][15] | |||||||||||||

Administrative divisions

[edit]

| Map | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Simplified Chinese[16][17] | Pinyin | Population (2003 est.)[citation needed][18] |

Area (km2)[19] | Density (/km2) | |

| Pingcheng District | 平城区 | Píngchéng Qū | 580,000 | 246 | 2,358 | |

| Yungang District | 云冈区 | Yúngāng Qū | 280,000 | 684 | 409 | |

| Xinrong District | 新荣区 | Xīnróng Qū | 110,000 | 1,102 | 109 | |

| Yunzhou District | 云州区 | Yúnzhōu Qū | 170,000 | 1,501 | 113 | |

| Yanggao County | 阳高县 | Yánggāo Xiàn | 290,000 | 1,678 | 173 | |

| Tianzhen County | 天镇县 | Tiānzhèn Xiàn | 210,000 | 1,635 | 128 | |

| Guangling County | 广灵县 | Guǎnglíng Xiàn | 180,000 | 1,283 | 140 | |

| Lingqiu County | 灵丘县 | Língqiū Xiàn | 230,000 | 2,720 | 85 | |

| Hunyuan County | 浑源县 | Húnyuán Xiàn | 350,000 | 1,965 | 178 | |

| Zuoyun County | 左云县 | Zuǒyún Xiàn | 140,000 | 1,314 | 107 | |

- Defunct – Kuang District (Chinese: 矿区; pinyin: Kuàngqū) is largely made up of separate mines throughout the metropolitan area.

Tourism

[edit]The Yungang Grottoes are a collection of shallow caves located 16 km (9.9 mi) west of Datong. There are over 50,000 carved images and statues of Buddhas and bodhisattvas within these grottoes, ranging from 4 to 700 centimetres (1.6 to 275.6 in). Most of these icons are around 1500 years old.It is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and one of the most important attractions in Datong.

Within the city itself, there are a few surviving sites of historical interest such as the Nine-Dragon Wall, the Huayan Monastery, and the Shanhua Temple. Further afield is the Hanging Temple built into a cliff face near Mount Heng. Most of the historical sites in this region date to the Liao, Jin and Ming dynasties, but the Hanging Temple dates to the Northern Wei dynasty (386–534).

The railway locomotive works (see below) began to attract increasing numbers of railway enthusiasts from the 1970s. When the construction of steam locomotives was phased out, the authorities did not want to lose this valuable tourism market, and pondered the possibility of developing a steam railway operating center as an attraction. A number of study visits were undertaken to the East Lancashire Railway at Bury, and a twinning arrangement was concluded with that town.

In 2010, work began on reconstructing the city's 14th century Ming dynasty defensive wall. The controversial reconstruction project was in its final phase at the end of 2014.[20] The documentary The Chinese Mayor[21] documents two years of vigorous and highly controversial (due to summary demolition of about 200,000 homes) effort by Mayor Geng Yanbo to push the reconstruction project forward.

-

The Hanging Temple

-

A tower on the City Wall

-

Pagoda at Huayan Temple

-

Huayan Temple

-

Lingyan Temple at Yungang Grottoes

-

Guard house on Datong City Wall

Culture

[edit]Datong is known for its knife-cut noodles[22] and Shanxi mature vinegar.[23]

Economy

[edit]The GDP per capita was ¥17,852 (US$2,570) per annum in 2008, ranked no. 242 among 659 Chinese cities. Coal mining is the dominant industry of Datong. Its history and development are very much linked to this commodity.

Development zones Datong Economic and Technological Development Zone

Due to its strategic position, it is also an important distribution and warehousing center for Shanxi, Hebei and Inner Mongolia.[24]

Datong is an old fashioned coal mining city, and still sits on significant reserves of this commodity. Consequently, it has developed a reputation as one of China's most polluted cities. The Datong Coal Mining Group is based here and is China's third largest such enterprise. Datong is indeed however an emerging economy, as the city seeks to loosen its dependence on coal, introduce more environmentally friendly and efficient methods of extraction and move into other areas of business services. The local government has continued to upgrade its pillar coal sector (and related industries like coal chemicals, power and metallurgy), while also developing "substitute industries" such as machinery manufacturing, tourism and distribution, warehousing and logistics services. This has had some impact. Datong's GDP grew by 5.1 percent in 2008 to RMB56.6 billion.[25]

While coal will continue to dominate, Datong has been identified as one of the key cities requiring redevelopment, with part of this being in environmental cleanup, rehabilitation and industrial refocusing. Datong is a pilot city for rehabilitation studies following years of pollution. To this end it has already struck up strong relationships with other cities worldwide with similar backgrounds, and has begun plans, for example, to develop a tourism base focused on steam engine technology with antique locomotives to be used along designated tracks.[26]

Datong has a large railway locomotive works, the 'Datong locomotive factory', opened in 1954. The works are notable as the main producer (~4,689 of 4,717) of the QJ or 'Advance Forward' (Chinese: 前进; pinyin: Qiánjìn) class of steam locomotive, built as late as 1988. Steam locomotive production ended in the late 1980s and the plant's main products (as of 2010) is mainline electric locomotives. The factory is currently owned by the China Railway Rolling Stock Corporation Ltd.

Main enterprises

[edit]- Datong Coal Mine Group (The third biggest coal-mining enterprise in China)[27]

- Datong Electric Locomotive Co., Ltd, (DELC) (The second biggest Elec-Locomotive enterprise in China)[28]

- Shanxi Diesel Engine Industries Corporation, Ltd, CNGC[29]

- Shanxi Synthetic Rubber Group Co., Ltd, CNCC[30]

- GD Power Datong No.2 Power Plant

- GD Power Datong Power Generation Co., Ltd[31]

- Shanxi Datang International Yungang Co-generation Co., Ltd.[32]

- China National Heavy Duty Truck Group Datong Gear CO., LTD[33]

Transportation

[edit]Education

[edit]Colleges and universities

[edit]- Datong University (大同大学)

- Datong Normal College(大同师范高等专科学校)

Major schools

[edit]- Datong No.1 Middle School (大同市第一中学)

- Datong No.2 Middle School (大同市第二中学)

- Datong Railway No. 1 Middle School (大同市铁路第一中学)

- Datong Locomotive Middle School (大同机车中学)

- Datong No.3 Middle School (大同市第三中学)

- BeiYue Middle School (北岳中学)

- Datong Experimental Secondary School (大同市实验中学)

- The No.1 Middle School of DCMG (Datong Coal Mine Group) (同煤一中)

- Datong No.14 Elementary School (大同市第十四小学)

- Datong No.18 Elementary School (大同市第十八小学)

- Datong Experimental Elementary School (大同市实验小学)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development, ed. (2019). China Urban Construction Statistical Yearbook 2017. Beijing: China Statistics Press. p. 46. Archived from the original on 18 June 2019. Retrieved 11 January 2020.

- ^ "China: Shānxī (Prefectures, Cities, Districts and Counties) - Population Statistics, Charts and Map".

- ^ 山西省统计局、国家统计局山西调查总队 (December 2021). 《山西统计年鉴-2021》. China Statistics Press. ISBN 978-7-5037-7824-7.

- ^ Hou Xiaorong (2009), 《秦代政区地理》 [An Atlas of Qin-Era Administrative Divisions], Beijing: Social Science Academic Press. (in Chinese)

- ^ Xiong (2009), s.v. "Daijun".

- ^ "Guandi Temple, Datong". www.art-and-archaeology.com. Retrieved 24 December 2022.

- ^ a b "Datong | China | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 24 December 2022.

- ^ "Drum Tower, Datong". www.art-and-archaeology.com. Retrieved 24 December 2022.

- ^ "Nine-Dragon Wall, Datong". www.art-and-archaeology.com. Retrieved 24 December 2022.

- ^ a b c d Su, Jiede (10 October 2020). "In Datong, a Crumbling Legacy of China's Most Extreme Urban Makeover". Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- ^ 中国气象数据网 – WeatherBk Data (in Simplified Chinese). China Meteorological Administration. Retrieved 26 August 2023.

- ^ "Experience Template" 中国气象数据网 (in Simplified Chinese). China Meteorological Administration. Retrieved 26 August 2023.

- ^ 中国地面国际交换站气候标准值月值数据集(1971-2000年). China Meteorological Administration. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ "Extreme Temperatures Around the World". Retrieved 16 September 2024.

- ^ "Datong Climate: 1991–2020". Starlings Roost Weather. Retrieved 9 August 2025.

- ^ 2016年统计用区划代码. National Bureau of Statistics of the People's Republic of China.

- ^ "历史沿革". Archived from the original on 4 February 2018. Retrieved 4 February 2018.

- ^ 大同市历史沿革_行政区划网(区划地名网). XZQH.org.

- ^ 山西省大同市地名介绍. www.tcmap.com.cn.

- ^ "Fake it to make it". South China Morning Post Magazine. Hong Kong. Retrieved 2 November 2014.

- ^ "The Chinese Mayor". IMDb.

- ^ https://inf.news/en/travel/988217c5317dd8bf472d38fff1883c87.html[permanent dead link] [bare URL]

- ^ "The best of Datong in 96 hours - Destinations".

- ^ China Briefing Business Guide Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. China-briefing.com. Retrieved on 25 February 2014.

- ^ "2008 Datong Economy Report". [permanent dead link]

- ^ China Briefing Business Guide: Datong Economy Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. China-briefing.com. Retrieved on 25 February 2014.

- ^ 大同煤矿集团公司. Datong Coal Mine Group. Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- ^ Datong Electric Locomotive Co., Ltd Of Cnr Archived 30 July 2012 at archive.today. Dtloco.com. Retrieved on 25 February 2014.

- ^ http://www.shanxi-engine.com.cn Archived 10 February 2005 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "ChinaBlueStar". www.china-bluestar.com. Archived from the original on 17 April 2009.

- ^ "English-guodan". www.cgdc.com.cn. Archived from the original on 3 October 2011.

- ^ Www.China-Cdt.Com Archived 12 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Www.China-Cdt.Com (29 December 2002). Retrieved on 25 February 2014.

- ^ china national heavy duty truck group datong gear co ltd Archived 15 January 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Dcgroup.com.cn. Retrieved on 25 February 2014.

Bibliography

[edit]- Xiong, Victor Cunrui (2009), Historical Dictionary of Medieval China, Historical Dictionaries of Ancient Civilizations and Historical Eras, No. 19, Lanham: Scarecrow Press, ISBN 9780810860537.

Further reading

[edit]- Cotterell, Arthur (2008). The Imperial Capitals of China: An Inside View of the Celestial Empire. Pimlico, London. ISBN 978-1-84595-010-1.

External links

[edit]- The Chinese Mayor (documentary) on website International Documentary Festival Amsterdam (IDFA) free to watch as embedded video (hosted on VIMEO)

Datong (City) travel guide from Wikivoyage

Datong (City) travel guide from Wikivoyage- Official website

Datong

View on GrokipediaDatong is a prefecture-level city in northern Shanxi Province, People's Republic of China, covering 14,176 square kilometers with a population of 3.10 million as of 2022.[1] Historically known as Pingcheng, it served as the capital of the Northern Wei dynasty from 398 to 494 AD, during which the Xianbei rulers promoted Buddhism and initiated major cultural projects.[2] The city is defined by its ancient heritage, particularly the Yungang Grottoes, a complex of 252 caves containing over 51,000 Buddhist statues carved primarily between 460 and 525 AD, recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage site for exemplifying early Chinese Buddhist art.[3] Geographically situated in the Datong Basin at an elevation of about 1,000 meters, Datong borders Inner Mongolia to the north and Hebei to the east, featuring a semi-arid climate and loess landscapes conducive to its historical cave constructions.[1] Economically, it transitioned from a coal-mining powerhouse—producing over 3 billion tonnes since 1949, earning it the moniker "China's Coal Capital"—to a focus on tourism and culture, with tourism revenue surging from 16.28 billion yuan in 2012 to 76.21 billion yuan in 2019 amid diversification into new energy and modern industries.[4] This shift included large-scale urban renewal starting in 2008, restoring the ancient city walls and heritage sites, though efforts under former mayor Geng Yanbo involved demolishing thousands of modern structures to reconstruct faux-antique facades, sparking controversies over resident displacements, high costs exceeding 20 billion yuan, and authenticity.[5] Notable achievements include designation as a national historical and cultural city, hosting over 3,000 cultural relics, and emerging as a transportation hub with improved rail and air links supporting its role as a "sculpture capital" and garden city.[1]

2019.jpg/250px-The_skyline_of_Datong(Southgate)2019.jpg)

2019.jpg/2000px-The_skyline_of_Datong(Southgate)2019.jpg)