Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Technophobia

View on Wikipedia

Technophobia (from Greek τέχνη technē, "art, skill, craft"[1] and φόβος phobos, "fear"[2]), also known as technofear, is the fear or dislike of, or discomfort with, advanced technology or complex devices, especially personal computers, smartphones, and tablet computers.[3] A 2018 study proposed a new conceptual and empirical definition of technophobia based on a critical literature review and data analysis results:

Technophobia is an irrational fear and/or anxiety that individuals form as a response to a new stimulus that comes in the form of a technology that modifies and/or changes the individual’s normal or previous routine in performing a certain job/task. Individuals may display active, physical reactions (fear) such as avoidance and/or passive reactions (anxiety) such as distress or apprehension.[4]

Although there are numerous interpretations of technophobia, they become more complex as technology continues to evolve. The term is generally used in the sense of an irrational fear, but others contend fears are justified. It is the opposite of technophilia.

Larry Rosen, a research psychologist, computer educator, and professor at California State University, Dominguez Hills, suggests that there are three dominant subcategories of technophobes – the "uncomfortable users", the "cognitive computerphobes", and "anxious computerphobes".[5] First receiving widespread notice during the Industrial Revolution, technophobia has been observed to affect various societies and communities throughout the world. This has caused some groups to take stances against some modern technological developments in order to preserve their ideologies. In some of these cases, the new technologies conflict with established beliefs, such as the personal values of simplicity and modest lifestyles.

Examples of technophobic ideas can be found in multiple forms of art, ranging from literary works such as Frankenstein to films like The Terminator. Many of these works portray a darker side to technology, as perceived by those who are technophobic. As technologies become increasingly complex and difficult to understand, people are more likely to harbor anxieties relating to their use of modern technologies.

Prevalence

[edit]A study published in the journal Computers in Human Behavior was conducted between 1992 and 1994 surveying first-year college students across various countries.[6] The overall percentage of the 3,392[7] students who responded with high-level technophobic fears was 29%.[7] In comparison, Japan had 58% high-level technophobes and Mexico had 53%.[7]

A published report in 2000 stated that roughly 85–90% of new employees at an organization may be uncomfortable with new technology, and are technophobic to some degree.[8]

History

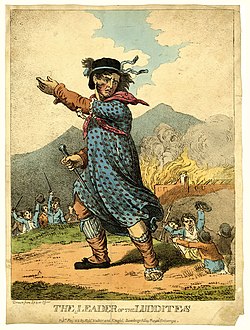

[edit]Technophobia began to gain attention as a movement in England with the dawn of the Industrial Revolution. With the development of new machines able to do the work of skilled craftsmen using unskilled, low-wage labor, those who worked a trade began to fear for their livelihoods. In 1675, a group of weavers destroyed machines that replaced their jobs. By 1727, the destruction had become so prevalent that Parliament made the demolition of machines a capital offense. This action, however, did not stop the tide of violence. The Luddites, a group of anti-technology workers, united under the name "Ludd" in March 1811, removing key components from knitting frames, raiding houses for supplies, and petitioning for trade rights while threatening greater violence. Poor harvests and food riots lent aid to their cause by creating a restless and agitated population for them to draw supporters from.[9]

The 19th century was also the beginning of modern science, with the work of Louis Pasteur, Charles Darwin, Gregor Mendel, Michael Faraday, Henri Becquerel, and Marie Curie, and inventors such as Nikola Tesla, Thomas Edison and Alexander Graham Bell. The world was changing rapidly, too rapidly for many, who feared the changes taking place and longed for a simpler time. The Romantic movement exemplified these feelings. Romantics tended to believe in imagination over reason, the "organic" over the mechanical, and a longing for a simpler, more pastoral time. Poets like William Wordsworth and William Blake believed that the technological changes that were taking place as a part of the industrial revolution were polluting their cherished view of nature as being perfect and pure.[10]

After World War II, a fear of technology continued to grow, catalyzed by the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. With nuclear proliferation and the Cold War, people began to wonder what would become of the world now that humanity had the power to manipulate it to the point of destruction. Corporate production of war technologies such as napalm, explosives, and gases during the Vietnam War further undermined public confidence in technology's worth and purpose.[11] In the post-WWII era, environmentalism also took off as a movement. The first international air pollution conference was held in 1955 and, in the 1960s, investigations into the lead content of gasoline sparked outrage among environmentalists. In the 1980s, the depletion of the ozone layer and the threat of global warming began to be taken more seriously.[12]

Luddites

[edit]

Several societal groups are considered technophobic, the most recognisable of which are the Luddites. Many technophobic groups revolt against modern technology because of their beliefs that these technologies are threatening their ways of life and livelihoods.[13] The Luddites were a social movement of British artisans in the 19th century who organized in opposition to technological advances in the textile industry.[9] These advances replaced many skilled textile artisans with comparatively unskilled machine operators. The 19th century British Luddites rejected new technologies that impacted the structure of their established trades, or the general nature of the work itself.

Resistance to new technologies did not occur when the newly adopted technology aided the work process without making significant changes to it. The British Luddites protested the application of the machines, rather than the invention of the machine itself. They argued that their labor was a crucial part of the economy, and considered the skills they possessed to complete their labor as property that needed protection from the destruction caused by the autonomy of machines.[14]

Use of modern technologies among Old Order Anabaptists

[edit]Groups considered by some people to be technophobic are the Amish and other Old Order Anabaptists. The Amish follow a set of moral codes outlined in the Ordnung, which rejects the use of certain forms of technology for personal use. Donald B. Kraybill, Karen M. Johnson-Weiner, and Steven M. Nolt state in their book The Amish:

More significantly the Amish modify and adapt technology in creative ways to fit their cultural values and social goals. Amish technologies are diverse, complicated and ever-changing.[15]

What the Amish do, is selective use of modern technologies in order to maintain their belief and culture.[16]

Technophobia in arts

[edit]

An early example of technophobia in fiction and popular culture is Mary Shelley's Frankenstein.[17]

Technophobia achieved commercial success in the 1980s with the movie The Terminator, in which a computer becomes self-aware, and decides to kill all humans.[17]

Shows such as Doctor Who have tackled the topic of technophobia – most specifically in the episode "The Robots of Death", with a character displaying a great fear of robots due to their lack of body language, described by the Fourth Doctor as giving them the appearance of "dead men walking". Series consultant Kit Pedler also used this fear as a basis for the inspiration of classic Doctor Who monsters the Cybermen, with the creatures being inspired by his own fear of artificial limbs becoming so common that it would become impossible to know when someone had stopped being a man and become simply a machine.

Virtuosity (1995) speaks of a virtual serial killer who manages to escape to the real world. He goes on a rampage before he is stopped. This is a true technophobic movie in that its main plot is about technology gone wrong. It introduces a killer who blatantly destroys people.[18]

Avatar is exemplary of technology's hold on humans who are empowered by it and visually demonstrates the amount of terror it instills upon those native to the concept. It enforces the notion that foreign creatures from Pandora are not only frightened by technology, but it is something they loathe; its potential to cause destruction could exceed their very existence. In contrast, the film itself used advanced technology such as the stereoscope in order to give viewers the illusion of physically taking part in an experience that would introduce them to a civilization struggling with technophobia.[19]

A 1960 episode of The Twilight Zone called "A Thing About Machines" deals with one man's hatred for modern things such as electric razors, televisions, electric typewriters, and clocks.[20][21]

See also

[edit]- Anti-consumerism – Sociopolitical ideology involving intentionally and meaningfully reducing consumption

- Erewhon – 1872 utopian novel by Samuel Butler

- Enshittification – Systematic decline in online platform quality

- Minimalism § Minimalist lifestyle

- Neo-Luddism – Philosophy opposing modern technology

- Ted Kaczynski – American domestic terrorist (1942–2023)

References

[edit]- ^ τέχνη, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- ^ φόβος, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- ^ "Definition of "Technophobia"". Dictionary.reference.com. Retrieved 2008-07-29.

(1) tech·no·pho·bi·a (těk'nə-fō'bē-ə) n. Fear of or aversion to technology, especially computers and high technology. -Related forms: tech'no·phobe' n., tech'no·pho'bic (-fō'bĭk) adj."— (American Heritage Dictionary)

(2) "tech·no·pho·bi·a /ˌtɛknəˈfoʊbiə/ - Show Spelled Pronunciation [tek-nuh-foh-bee-uh] –noun abnormal fear of or anxiety about the effects of advanced technology. [Origin: 1960–65; techno- + -phobia] —Related forms: tech·no·phobe, noun – (Dictionary.com unabridged (v1.1) based on the Random House unabridged Dictionary, © Random House, Inc. 2006.) - ^ Khasawneh, Odai Y. (2018). "Technophobia: Examining its hidden factors and defining it". Technology in Society. 54: 93–100. doi:10.1016/j.techsoc.2018.03.008.

- ^ Gilbert, David, Liz Lee-Kelley, and Maya Barton. "Technophobia, gender influences and consumer decision-making for technology-related products." European Journal of Innovation Management 6.4 (2003): pp. 253–263. Print.

- ^ Weil, Michelle M.; Rosen, Larry D. (1995). "A Study of Technological Sophistication and Technophobia in University Students From 23 Countries". Computers in Human Behavior. 11 (1): 95–133. doi:10.1016/0747-5632(94)00026-E.

Over a two-year period, from 1992–1994, data were collected from 3,392 first year university students in 38 universities from 23 countries on their level of technological sophistication and level of technophobia.

- ^ a b c Weil, Michelle M.; Rosen, Larry D. (1995). "A Study of Technological Sophistication and Technophobia in University Students From 23 Countries". Computers in Human Behavior. 11 (1): 95–133. doi:10.1016/0747-5632(94)00026-E.

Table 2. Percentage of Students in each country who possessed high levels of technophobia

; several points are worth noting from Table 2. First, a group of countries including Indonesia, Poland, India, Kenya, Saudi Arabia, Japan, Mexico and Thailand show large percentages (over 50%) of technophobic students. In contrast, there are five countries which show under 30% technophobes (US, Yugoslavia – Croatia, Singapore, Israel and Hungary). The remaining countries were in between these two groupings. - ^ "Index – Learning Circuits – ASTD". Learning Circuits. Archived from the original on 2008-05-11. Retrieved 2010-06-02.

- ^ a b Kevin Binfield. "Luddite History – Kevin Binfield – Murray State University". Campus.murraystate.edu. Archived from the original on 2010-06-10. Retrieved 2010-06-02.

- ^ "Romanticism". Wsu.edu. Archived from the original on 2010-05-28. Retrieved 2010-06-02.

- ^ Goodyear, Anne Collins (2008). "From Technophilia to Technophobia: The Impact of the Vietnam". Leonardo. 41 (2): 169–173. doi:10.1162/leon.2008.41.2.169. S2CID 57570414.

- ^ "Environmental History Timeline". Runet.edu. 1969-06-22. Retrieved 2010-06-02.

- ^ "The Luddites". Regent.edu. Archived from the original on 2010-05-29. Retrieved 2010-06-02.

- ^ Randall, Adrien (1997). "Reinterpreting 'Luddism': Resistance to New Technology in the British Industrial Revolution" Resistance to New Technology: Nuclear Power, Information Technology and Biotechnology. Cambridge University Press. pp. 57–80. ISBN 9780521455183.

- ^ Donald B. Kraybill, Karen M. Johnson-Weiner and Steven M. Nolt: The Amish, Baltimore 2013, p. 313.

- ^ Look Who's Talking – an article about the selective use of technologies among the Amish.

- ^ a b "Critical Essay – Old Games, Same Concerns: Examining First Generation Video Games Through Popular Press Coverage from 1972–1985 | Technoculture". tcjournal.org. Retrieved 2019-11-08.

- ^ Technophobia: Science Fiction Visions of Posthuman Technology

- ^ Man of Extremes|Dana Goodyear. The New Yorker. October 19, 2009.

- ^ Twilight Zone - A Thing About Machines

- ^ Exploring The Twilight Zone #40: A Thing About Machines - Film School Rejects

Further reading

[edit]- Brosnan, M. (1998) Technophobia: The psychological impact of information technology. Routledge.

- Dan Dinello Technophobia: Science Fiction Visions of Posthuman Technology

- "Environmental History Timeline". 20 July 2008.

External links

[edit] The dictionary definition of technophobia at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of technophobia at Wiktionary Media related to Technophobia at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Technophobia at Wikimedia Commons