Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

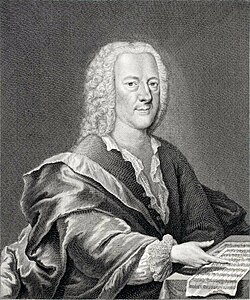

Georg Philipp Telemann

View on Wikipedia

Georg Philipp Telemann (German: [ˈɡeːɔʁk ˈfiːlɪp ˈteːləman]; 24 March [O.S. 14 March] 1681 – 25 June 1767) was a German Baroque composer and multi-instrumentalist. He is one of the most prolific composers in history,[1] at least in terms of surviving works.[2] Telemann was considered by his contemporaries to be one of the leading German composers of the time, and he was compared favourably both to his friend Johann Sebastian Bach, who made Telemann the godfather and namesake of his son Carl Philipp Emanuel, and to George Frideric Handel, whom Telemann also knew personally.

Key Information

Almost completely self-taught in music, he became a composer against his family's wishes. After studying in Magdeburg, Zellerfeld, and Hildesheim, Telemann entered the University of Leipzig to study law, but eventually settled on a career in music. He held important positions in Leipzig, Sorau, Eisenach, and Frankfurt before settling in Hamburg in 1721, where he became musical director of that city's five main churches. While Telemann's career prospered, his personal life was always troubled: his first wife died less than two years after their marriage, and his second wife had extramarital affairs and accumulated a large gambling debt before leaving him. As part of his duties, he wrote a considerable amount of music for educating organists under his direction. This includes 48 chorale preludes and 20 small fugues (modal fugues) to accompany his chorale harmonisations for 500 hymns. His music incorporates French, Italian, and German national styles, and he was at times even influenced by Polish popular music. He remained at the forefront of all new musical tendencies, and his music stands as an important link between the late Baroque and early Classical styles. The Telemann Museum in Hamburg is dedicated to him.

Life

[edit]Early life (1681–1712)

[edit]

Telemann was born in Magdeburg,[3] then the capital of the semi-autonomous Duchy of Magdeburg within the Electorate of Brandenburg, in the Holy Roman Empire. His father Heinrich, deacon at the Heilig-Geist-Kirche (Magdeburg), died when Telemann was four.[4] The future composer received his first music lessons at 10, from a local organist, and became immensely interested in music in general, and composition in particular. Despite opposition from his mother and relatives, who forbade any musical activities, Telemann found it possible to study and composed in secret, even creating an opera at the age of 12.[5]

In 1697, after studies at the Domschule in Magdeburg and at a school in Zellerfeld, Telemann was sent to the famous Gymnasium Andreanum at Hildesheim,[4] where his musical talent flourished, supported by school authorities, including the rector himself. Telemann was becoming equally adept both at composing and performing, teaching himself flute, oboe, violin, viola da gamba, recorder, double bass, and other instruments.[6] In 1701 he graduated from the Gymnasium and went to Leipzig to become a student at the Leipzig University, where he intended to study law.[6] He ended up becoming a professional musician, regularly composing works for the Nikolaikirche and even St. Thomas (Thomaskirche).[6] In 1702 he became director of the municipal opera house Opernhaus auf dem Brühl, and later music director at the Neukirche. Prodigiously productive, Telemann supplied a wealth of new music for Leipzig, including several operas, one of which was his first major opera, Germanicus. However, he became engaged in a conflict with the cantor of the Thomaskirche, Johann Kuhnau. The conflict intensified when Telemann started employing numerous students for his projects, including those who were Kuhnau's, from the Thomasschule.[7]

Telemann left Leipzig in 1705 at the age of 24, after receiving an invitation to become Kapellmeister for the court of Count Erdmann II of Promnitz at Sorau (now Żary, Poland). His career there was cut short in early 1706 by the hostilities of the Great Northern War, and after a short period of travels he entered the service of Duke Johann Wilhelm, in Eisenach where Johann Sebastian Bach was born.[6] He became Konzertmeister on 24 December 1708 and Secretary and Kapellmeister in August 1709. During his tenure at Eisenach, Telemann wrote a great deal of music: at least four annual cycles of church cantatas, dozens of sonatas and concertos, and other works. In 1709, he married Amalie Louise Juliane Eberlin, lady-in-waiting to the Countess of Promnitz and daughter of the musician Daniel Eberlin.[4] Their daughter was born in January 1711. The mother died soon afterwards, leaving Telemann depressed and distraught.[8]

Frankfurt (1712–1721)

[edit]After around a year he sought another position, and moved to Frankfurt on 18 March 1712 at the age of 31, to become city music director and Kapellmeister at the Barfüßerkirche[4] and St. Catherine's Church.[6] In Frankfurt, he fully gained his mature personal style. Here, as in Leipzig, he was a powerful force in the city's musical life, creating music for two major churches, civic ceremonies, and various ensembles and musicians. By 1720 he had adopted the use of the da capo aria, which had been adopted by composers such as Alessandro Scarlatti. Operas such as Narciso, which was brought to Frankfurt in 1719, written in the Italian idiom of composition, made a mark on Telemann's output.[9]

On 28 August 1714, three years after his first wife had died, Telemann married again, Maria Catharina Textor, daughter of a Frankfurt council clerk.[4] They eventually had nine children. This was a source of much personal happiness, and helped him produce compositions. Telemann continued to be extraordinarily productive and successful, even augmenting his income by working for Eisenach employers as a Kapellmeister von Haus aus, that is, regularly sending new music while not actually living in Eisenach. Telemann's first published works also appeared during the Frankfurt period. His output increased rapidly, for he fervently composed overture-suites and chamber music, most of which is unappreciated.[9] These works included his 6 Sonatas for solo violin, known as the Frankfurt Sonatas, published in 1715. In the latter half of the Frankfurt period, he composed an innovative work, his Viola Concerto in G major, which is twice the length of his violin concertos.[10] Also, here he composed his first choral masterpiece, his Brockes Passion, in 1716.

Hamburg (1721–1767)

[edit]Telemann accepted the invitation to work in Hamburg as Kantor of the Johanneum Lateinschule, and music director of the five largest churches in 1721.[6] Soon after arrival, Telemann encountered some opposition from church officials who found his secular music and activities to be too much of a distraction for both Telemann himself and the townsfolk. The next year, when Johann Kuhnau died and the city of Leipzig was looking for a new Thomaskantor, Telemann applied for the job and was approved, yet declined after Hamburg authorities agreed to give him a suitable raise. After another candidate, Christoph Graupner, declined, the post went to Johann Sebastian Bach.[6]

Telemann took a few small trips outside Germany at this time. However, later in the Hamburg period he travelled to Paris and stayed for eight months, 1737 into 1738. He heard and was impressed by Castor et Pollux, an opera by French composer Jean-Philippe Rameau. From then on, he incorporated the French operatic style into his vocal works. Before then, his influence was primarily Italian and German.[11] Apart from that, Telemann remained in Hamburg for the rest of his life. A vocal masterpiece of this period is his St Luke Passion from 1728, which is a prime example of his fully matured vocal style.

His first years there were plagued by marital troubles: his wife's infidelity, and her gambling debts, which amounted to a sum larger than Telemann's annual income. The composer was saved from bankruptcy by the efforts of his friends, and by the numerous successful music and poetry publications Telemann made during the years 1725 to 1740. By 1736 husband and wife were no longer living together because of their financial disagreements. Although still active and fulfilling the many duties of his job, Telemann became less productive in the 1740s, when he was in his 60s. He took up theoretical studies, as well as hobbies such as gardening and cultivating exotic plants, something of a fad in Hamburg at that time, and a hobby shared by Handel. Most of the music of the 1750s appears to have been parodied from earlier works. Telemann's eldest son Andreas died in 1755, and Andreas' son Georg Michael Telemann was raised by the aging composer. Troubled by health problems and failing eyesight in his last years, Telemann was still composing into the 1760s. He died, aged 86, on the evening of 25 June 1767 from what was recorded at the time as a "chest ailment." He was succeeded in his Hamburg post by his godson, Johann Sebastian Bach's second son, Carl Philipp Emmanuel Bach.

Legacy and influence

[edit]Telemann was one of the most prolific major composers of all time:[12] his all-encompassing oeuvre comprises more than 3,000 compositions, half of which have been lost, and most of which have not been performed since the 18th century. From 1708 to 1750, Telemann composed 1,043 sacred cantatas and 600 overture-suites, and types of concertos for combinations of instruments that no other composer of the time employed.[9] The first accurate estimate of the number of his works was provided by musicologists only during the 1980s and 1990s, when extensive thematic catalogues were published. During his lifetime and the latter half of the 18th century, Telemann was very highly regarded by colleagues and critics alike. Numerous theorists (Marpurg, Mattheson, Quantz, and Scheibe, among others) cited his works as models, and major composers such as J.S. Bach and Handel bought and studied his published works. He was immensely popular not only in Germany but also in the rest of Europe: orders for editions of Telemann's music came from France, Italy, the Netherlands, Belgium, Scandinavian countries, Switzerland, and Spain. It was only in the early 19th century that his popularity came to a sudden halt. Most lexicographers started dismissing him as a "polygraph" who composed too many works, a Vielschreiber for whom quantity came before quality. Such views were influenced by an account of Telemann's music by Christoph Daniel Ebeling, a late-18th-century critic who in fact praised Telemann's music and made only passing critical remarks of his productivity. After the Bach revival, Telemann's works were judged as inferior to Bach's and lacking in deep religious feeling.[4][13] For example, by 1911, the Encyclopædia Britannica lacked an article about Telemann, and in one of its few mentions of him referred to "the vastly inferior work of lesser composers such as Telemann" in comparison to Handel and Bach.[14]

Particularly striking examples of such judgements were produced by noted Bach biographers Philipp Spitta and Albert Schweitzer, who criticized Telemann's cantatas and then praised works they thought were composed by Bach, but which were composed by Telemann.[13] The last performance of a substantial work by Telemann (Der Tod Jesu) occurred in 1832, and it was not until the 20th century that his music started being performed again. The revival of interest in Telemann began in the first decades of the 20th century and culminated in the Bärenreiter critical edition of the 1950s. Today each of Telemann's works is usually given a TWV number, which stands for Telemann-Werke-Verzeichnis (Telemann Works Catalogue).

Telemann's music was one of the driving forces behind the late Baroque and the early Classical styles. Starting in the 1710s he became one of the creators and foremost exponents of the so-called German mixed style, an amalgam of German, French, Italian and Polish styles.[6] Over the years, his music gradually changed and started incorporating more and more elements of the galant musical style, but he never completely adopted the ideals of the nascent Classical era: Telemann's style remained contrapuntally and harmonically complex, and already in 1751 he dismissed much contemporary music as too simplistic. Composers he influenced musically included pupils of J.S. Bach in Leipzig, such as Wilhelm Friedemann Bach, Carl Philipp Emmanuel Bach and Johann Friedrich Agricola, as well as those composers who performed under his direction in Leipzig (Christoph Graupner, Johann David Heinichen and Johann Georg Pisendel), composers of the Berlin lieder school, and finally, his numerous pupils, none of whom, however, became major composers.

Equally significant for the history of music were Telemann's publishing activities. By pursuing exclusive publication rights for his works, he set one of the most important early precedents for regarding music as the intellectual property of the composer. The same attitude informed his public concerts, where Telemann frequently performed music originally composed for ceremonies attended only by a select few members of the upper class.[4]

Partial list of works

[edit]Operas

[edit]Passions

[edit]Cantatas

[edit]- Cantata Cycle 1716–1717

- Harmonischer Gottes-Dienst

- Die Donner-Ode ("The Ode of Thunder") TWV 6:3a-b

- Du bleibest dennoch unser Gott (Erstausgabe 1730)

- Ihr Völker, hört

- Ino (1765)

- Sei tausendmal willkommen (Erstausgabe 1730)

- Die Tageszeiten ("The Times of the Day") (1757)

- Gott, man lobet dich in der Stille, Cantata for the Peace of Paris, 1763, for 5-part chorus, flute, 2 oboes, bassoon, 3 trumpets, 2 horns, strings & continuo, TWV 14:12

- not by Telemann: Der Schulmeister ("The Schoolmaster" 1751), by Christoph Ludwig Fehre.

Oratorios

[edit]- Hamburger Admiralitätsmusik several years including TWV 24:1

- Der Tag des Gerichts (The Day of Judgement) (1761–62)

- Hamburgische Kapitänsmusik (various years)

- Der Tod Jesu (The Death of Jesus) TWV 5:6 (1755)

- Die Auferstehung und Himmelfahrt Jesu" (The Resurrection and Ascension of Jesus) TWV 6:6, (1760)

- Trauermusik for Emperor Karl VII (1745) Ich hoffete aufs Licht, TWV 4:13

- Trauermusik for Hamburg mayor Garlieb Sillem Schwanengesang TWV 4:6

- Der aus der Löwengrube errettete Daniel ("Daniel Delivered from the Lion's Den") (1731) [This has been incorrectly attributed to Handel]

- Reformations-Oratorium 1755 Holder Friede, Heilger Glaube TWV 13:18[15]

Orchestral suites

[edit]- Grillen-symphonie TWV 50:1

- Ouverture (Wassermusik: Hamburger Ebb und Fluth) TWV 55:C3

- Ouverture des nations anciens et modernes in G TWV 55:G4

- Ouverture in G minor TWV 55:g4

- Suite in A minor for recorder, strings, and continuo TWV 55:a2

- Overture: Alster Echo in F, for 4 horns, 2 oboes, bassoon, strings and continuo, TWV55:F11

Chamber music

[edit]- Sinfonia Spirituosa in D major (2 violins, viola & continuo, trumpet ad libitum) TWV 44:1

- Tafelmusik (1733) ('Tafelmusik' refers to music meant to accompany a meal)

- Der getreue Musikmeister (1728), a musical journal containing 70 small vocal and instrumental compositions

- Twelve Paris quartets in two sets of six (Quadri a violino, flauto traversiere, viola da gamba o violoncello, e fondamento, 1730, reprinted as Six quatuors, 1736; Nouveaux quatuors en six suites, 1738) for flute, violin, viola da gamba or cello, continuo, TWV 43:G1, D1, A1, g1, e1, h1 (first set), TWV 43:D3, a2, G4, h2, A3, e4 (second set)

- Twelve Fantasias for Transverse Flute without Bass TWV 40:2–13

- Twelve Fantasias for Violin without Bass TWV 40:14–25

- Twelve Fantasias for Viola da Gamba solo TWV 40:26–37

- Sonates sans basse (Telemann) TWV 40:101–106

- Six Canonical Sonatas TWV 40: 118–123

- Six Concertos for Flute and Harpsichord TWV 42.

Keyboard

[edit]- 36 Fantasias for Keyboard TWV 33:1–36

- 6 Overtures for Keyboard TWV 32:5–10

- 6 Light Fugues with Small Fresh Additions TWV 30:21–26

Organ and theoretical

[edit]- 48 Chorale Preludes for Organ TWV 31:1–48

- 20 Easy Fugues in 4 parts TWV 30:1–20

- 500 chorale harmonizations

Concertos

[edit]Violin

[edit]- Violin Concerto in A major "Die Relinge" TWV 51:A4

- Concerto for Three Violins in F major, TWV 53:F1 (from Tafelmusik, part II)

- Four Concertos for Four Violins TWV 40:201–204

Viola

[edit]- Concerto in G major for Viola and String Orchestra, TWV 51:G9; the first known concerto for viola, still regularly performed today

- Concerto in G major for Two Violas and String Orchestra, TWV 52:G3

Horn

[edit]- Concerto for Two Horns in D major TWV 52:D1

- Concerto for Two Horns in D major TWV 52:D2

- Concerto for Horn and Orchestra in D major TWV 51:D8

- Concerto for Two Horns in F Major TWV 52:F3

- Concerto for Two Horns in F Major TWV 52:F4

- Concerto for Two Horns in E♭ Major TWV 52:Es1

- Concerto for Two Horns in E♭ and 2 Violins, TWV 54:Es1

- Concerto for Three Horns in D and Violin, TWV 54:D2

Trumpet

[edit]- Trumpet Concerto in D major, TWV 51:D7

- Concerto in D for Trumpet and 2 Oboes, TWV 53:D2

- Concerto in D for Trumpet, Violin and Violoncello, TWV 53:D5

- Concerto in D for 3 Trumpets, Timpani, 2 Oboes, TWV 54:D3

- Concerto in D for 3 Trumpets, Timpani, TWV 54:D4

Chalumeau

[edit]- Concerto in C major for 2 Chalumeaux, 2 Bassoons and Orchestra, TWV 52:C1

- Concerto in D minor for Two Chalumeaux and Orchestra, TWV 52:d1

Oboe

[edit]- Concerto in A major

- Concerto in C minor, TWV 51:c1

- Concerto in D minor

- Concerto in E minor

- Concerto in F minor

- Concerto in G major

Bassoon

[edit]- Concerto for Recorder and Bassoon in F major, TWV 52:F1

Recorder

[edit]- Concerto in C major, TWV 51:C1

- Concerto in F major, TWV 51:F1

- Concerto for Recorder and Viola da gamba in A minor, TWV 52:a1

- Concerto for 2 Recorders in A minor, TWV 52:a2

- Concerto for 2 Recorders in B♭ major, TWV 52:B1

Flute

[edit]- Concerto in D major, TWV 51:D2

- Concerto in E minor for Recorder and Flute, TWV 52:e1

- Concerto in B minor, TWV 41:h3

- Concerto in C minor, TWV 41:c3

- Twelve fantasias for solo flute, TWV 40:2-13

Sonatas

[edit]Sonata da chiesa, TWV 41:g5 (for Melodic instrument – Violin, Flute or Oboe, from Der getreue Musikmeister)

Oboe

[edit]- Sonata in A minor TWV 41:a3 (from Der getreue Musikmeister)

- Sonata in B♭ TWV 41:B6

- Sonata in E minor TWV 44:e6

- Sonata in G minor TWV 41:g6

- Sonata in G minor TWV 41:g10

Bassoon

[edit]- Sonata in F minor TWV 41:f1 (part of the collection Der getreue Musikmeister, 1728)

- Sonata in E♭ major TWV 41:EsA1

Media

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

- ^ The Guinness Book of World Records 1998, Bantam Books, p. 402. ISBN 0-553-57895-2.

- ^ See Phillip Huscher, Program Notes – Telemann Tafelmusik III Archived 3 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, 2007.

- ^ Einstein, Alfred (1929). "Telemann, Georg Philipp". Hugo Riemanns Musik-Lexikon (in German).

- ^ a b c d e f g Hirschmann, Wolfgang (2016). "Telemann, Georg Philipp (Pseudonym Melante)". Neue Deutsche Biographie. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

- ^ As Telemann claimed in his autobiography provided to and printed by Johann Mattheson (1681–1764) in the latter's Grundlage einer Ehren-Pforte (1740), p. 355: "... Ich eine ertappte hamburger Oper, Sigismundus, etwa im zwölfften Jahr meines Alters, in die Musik seßte, welche auch auf einer errichteten Bühne toll genug abegefungen wurde, und wohen ich selbst meinen Held ziemlich troßig vorstellte." [... About my twelfth year of age I took hold of a Hamburg opera, Sigismund, [and] set it to music, which was performed well enough on a home-made stage, and where I personally presented my hero pretty defiantly.]

- ^ a b c d e f g h Bergmann, Walter G. (2021). "Georg Philipp Telemann / German composer". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 1 April 2021.

- ^ Spitta, Phillip, Johann Sebastian Bach (publ 1873–1880) translated from the German (1884–1899) by Clara Bell and J.A. Fuller-Maitland, Dover 1951 (republished 1959, 1992, 2015), Vol II, pp. 204–207: "The direct connection between opera and sacred music which thus took form in the person of Telemann at once exerted its baleful influence... Kuhnau represented that the tendencies of the 'Operists' ... were destroying all feeling for true church music..." Spitta, ibid. Appendix B VII (actually B IV, p. 303): "... [In] Memorials of Kuhnau's, addressed to the Town Council and to the University on ... March 17, 1709... [Kuhlau] appeals to ... consider certain points... 8 & 9 refer to the numbers of the choir, and 10 complains again of the increasing influence of the opera; this, he says, causes the greatest mischief, for the better students, as soon as they have acquired... sufficient practice, long to find themselves among the Operisten"

- ^ Rolland, Romain (2017). Romain Rolland's Essays on Music. Allen, Towne & Heath. p. 109. ISBN 978-1-4437-3093-8.

- ^ a b c "Baroque Composers and musicians". Baroquemusic.org. 2013. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- ^ "Georg Philipp Telemann – Viola Concerto in G, TWV51:G9". Classical Archives. Retrieved 3 April 2016.

- ^ Wollny, Peter (1994). Notes on Telemann's St. Matthew Passion. hannsler classic. pp. 12–15.

- ^ Profile on Classic FM website

- ^ a b Zohn, Steven (2001). "Georg Philipp Telemann". In Sadie, Stanley; Tyrrell, John (eds.). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan Publishers. ISBN 978-1-56159-239-5.

- ^ Gadow, Hans (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 25 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 408.

- ^ Concerto: Das Magazin für Alte Musik, Vol. 22, p. 14, 2005: "Am 24. September erklingt dann in St. Anna erstmals wieder Georg Philipp Telemanns Oratorium Holder Friede, Heilger Glaube, das 1755 zum 200. Jubiläum des Augsburger Religionsfriedens entstanden ist."

External links

[edit]Further information on Telemann and his works

- Georg Philipp Telemann (Composer) Bach Cantatas Website.

- Georg Philipp Telemann at www

.baroquemusic .org - Partial list of Telemann publications and TWV numbers, Robert Poliquin, Université du Québec (archive from 13 August 2013. Retrieved 25 May 2015). (French)

- Telemann as opera composer from 1708–61, OperaGlass, Stanford University.

Modern editions

- Prima la musica! Commercially available performing editions of Telemann's music, as well as other baroque composers.

- Habsburger Verlag Modern performing editions of Telemann's cantatas edited by Eric Fiedler.

- Edition Musiklandschaften Modern performing editions of Telemann's yearly Passions from 1757 to 1767 edited by Johannes Pausch

Free sheet music

- Free scores by Georg Philipp Telemann at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- Free scores by Georg Philipp Telemann in the Choral Public Domain Library (ChoralWiki)

- Free scores, Cantatas, Archiv der kreuznacher-diakonie-kantorei.

- Free scores of Telemann's Harpsichord Fantasias TWV 33:1–36 at Brightcecilia Classical Music Forums

- The Mutopia Project has compositions by Georg Philipp Telemann