Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Teutons

View on Wikipedia

The Teutons (Latin: Teutones, Teutoni; Ancient Greek: Τεύτονες) were an ancient northern European tribe mentioned by Roman authors. The Teutons are best known for their participation, together with the Cimbri and other groups, in the Cimbrian War with the Roman Republic in the late second century BC.[1]

Some generations later, Julius Caesar compared them to the Germanic peoples of his own time, and used this term for all northern peoples located east of the Rhine. Later Roman authors followed his identification. However, there is no direct evidence about whether they spoke a Germanic language. Evidence such as the tribal name, and the names of their rulers, as they were written up by Roman historians, indicates a strong influence from Celtic languages. On the other hand, the indications that classical authors gave about the homeland of the Teutones is considered by many scholars to show that they lived in an area associated with early Germanic languages, and not in an area associated with Celtic languages.

Name

[edit]The ethnonym appears in Latin as Teutonēs or Teutoni in the plural, and less commonly as Teuton or Teutonus in the singular.[2] It transparently originates from the Proto-Indo-European stem *tewtéh₂-, meaning "people, tribe, crowd," (e.g. the Celtic deity Teutates whose name is understood as "god of the tribe"[3]), with the addition of the suffix -ones, which is frequently found in both Celtic (e.g., Lingones, Senones) and Germanic (e.g., Ingvaeones, Semnones) tribal names during the Roman period. The term conveys the idea of a "mass of people", in contrast to distinguished individuals—such as leaders or heroes—or those belonging to a more elite group. It may have originally meant "people under arms" in Proto-Indo-European, as suggested by the Hittite tuzzi- and the Luwian tuta ("army").[4]

The name Teutones can be interpreted either as Celtic, from the Proto-Celtic *towtā ("people, tribe)", or as pre-Germanic. Its recorded spellings do not match the later Proto-Germanic form *þeudō- ("nation, people, folk," cf. Gothic þiuda), which suggests that if it is indeed Germanic, it must derive from an earlier stage of the language (prior to the first consonantal shift), unless the Greek and Latin renditions are corrupt and do not accurately represent the original form. The stem tewtéh₂- is so widespread in Indo-European languages that linking the ethnonym to other names with the same origin, such as the Teutoburg Forest (Teutoburgensis saltus), is challenging.[4]

Later on, beginning with ninth-century monastic Latin texts, the term Teuton came to refer specifically to speakers of West Germanic languages—a usage that has persisted into modern times. Originally, it was used as a learned alternative to the similar-sounding term theodiscus, which was a Latinized form of the contemporary West Germanic word meaning "of the people".[5] By extension, the adjective "Teutonic" has often been used more broadly to mean the same as "Germanic".[2]

Linguistic affiliations

[edit]The Teutons commonly are classified as a Germanic tribe and thought probably to have spoken a Germanic language, although the evidence is fragmentary. However, because of the non-Germanic, possibly Celtic, form of the names of both the Teutones and their associates the Cimbri, as well as the personal names known from these tribes, some historians have suggested a Celtic origin for the Teutones.[6][7]

The earliest classical writers classified the Teutones as Celts; more generally, they did not distinguish between Celtic and Germanic peoples. Apparently, this distinction was first made by Julius Caesar, whose main concern was to argue that raids into southern Gaul and Italy by northern peoples who were less softened by Mediterranean civilization, should be seen in Rome as a systematic problem that can repeat in the future, and thereby demanded pre-emptive military action. This was his justification for invading northern Gaul.[8]

After Caesar, Strabo (died circa AD 24)[9] and Marcus Velleius Paterculus (died circa AD 31)[10] classify Teutons as Germanic peoples.[11] Pliny also classified them this way and specified that they were among the Ingaevones, related to the Cimbri and Chauci.[12]

Homeland

[edit]Plutarch in his biography of Marius, who fought the Teutones, wrote that they and the Cimbri "had not had intercourse with other peoples, and had traversed a great stretch of country, so that it could not be ascertained what people it was nor whence they had set out". He reported that there were different conjectures: that they were "some of the German peoples which extended as far as the northern ocean"; that they were "Galloscythians", a mixture of Scythians and Celts who had lived as far east as the Black Sea, or that the Cimbri were Cimmerians, from even farther east.[13]

The Fourth Century BC traveller, Pytheas, as reported by Pliny the Elder (died AD 79), described the Teutones as neighbours of the northern island of Abalus where amber washed up in the spring, and was traded by the Teutones. Abalus was one day's sail from a tidal marsh or estuary facing the ocean (aestuarium) called Metuonis inhabited by another Germanic people, the Guiones (probably either the Inguaeones, or Gutones).[14]

Pomponius Mela (died circa 45 CE) stated that the Teutons lived on a large island, Codannovia, which was one of a group of islands in a large bay called Codanus, open to the ocean. Most scholars have interpreted this bay as being the Baltic Sea,[15] and Codannovia as being Scandinavia.

31. On the other side of the Albis [Elbe], the huge Codanus Bay [Baltic Sea] is filled with big and small islands. For this reason, where the sea is received within the fold of the bay, it never lies wide open and never really looks like a sea but is sprinkled around, rambling and scattered like rivers, with water flowing in every direction and crossing many times. Where the sea comes into contact with the mainland, the sea is contained by the banks of islands, banks that are not far offshore and that are virtually equidistant everywhere. There the sea runs a narrow course like a strait, then, curving, it promptly adapts to a long brow of land. 32. On the bay are the Cimbri and the Teutoni; farther on, the farthest people of Germany, the Hermiones.

[...]

54. The thirty Orcades [Orkney Islands] are separated by narrow spaces between them; the seven Haemodae [Denmark] extend opposite Germany in what we have called Codanus Bay; of the islands there, Scandinavia [sic: the manuscript has Codannavia[16]], which the Teutoni still hold, stands out as much for its size as for its fertility besides.

Surviving texts based on the work of the geographer Ptolemy mentioned both Teutones and "Teutonoaroi" in Germania, but this is in a part of his text that has become garbled in surviving copies. Gudmund Schütte proposed that the two peoples should be understood as one, but that different versions of works based on that of Ptolemy used literary sources such as Pliny and Mela to place them in different positions somewhere near the Cimbri, in a part of the landscape they did not have good information for – either in Zealand or Scandinavia, or else somewhere on the southern Baltic coast.[17]

According to scholar Stefan Zimmer (2005), since both the name of the Teutones and Crimbri left traces in place names from Jutland (in Thy and Himmerland, respectively), "there is no reason to doubt the ancient accounts of the origins of the two tribes".[4]

Cimbrian War

[edit]After achieving decisive victories over the Romans at Noreia and Arausio in 105 BC, the Cimbri and Teutones divided their forces. Gaius Marius then defeated them separately in 102 BC and 101 BC respectively, ending the Cimbrian War. The defeat of the Teutones occurred at the Battle of Aquae Sextiae (near present-day Aix-en-Provence).

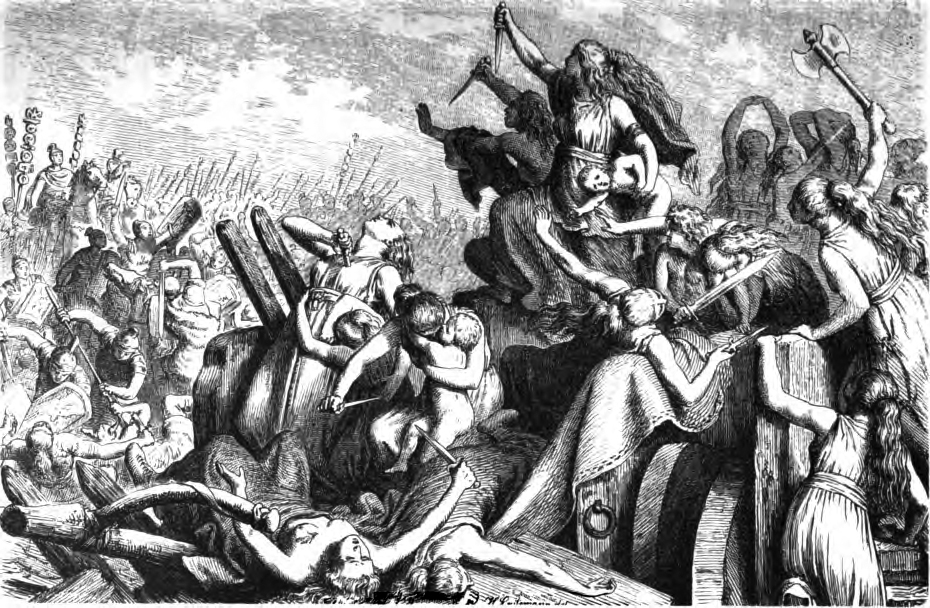

According to the writings of Valerius Maximus and Florus, the king of the Teutones, Teutobod, was taken in irons after the Teutones were defeated by the Romans. Under the conditions of the surrender, three hundred married women were to be handed over to the victorious Romans as concubines and slaves. When the matrons of the Teutones heard of this stipulation, they begged the consul that they might instead be allowed to minister in the temples of Ceres and Venus. When their request was denied, the Teutonic women slew their own children. The next morning, all the women were found dead in each other's arms, having strangled each other during the night. Their joint martyrdom passed into Roman legends of Teutonic fury.[18]

Reportedly, some surviving captives participated as the rebelling gladiators in the Third Servile War of 73–71 BC.[19]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Thompson, Edward Arthur; Dobson, John Frederick (2012). "Teutones". In Hornblower, Simon; Spawforth, Antony; Eidinow, Esther (eds.). The Oxford Classical Dictionary (4 ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191735257. Retrieved January 25, 2020.

Teutones, a Germanic tribe, known chiefly from their migration with the Cimbri...

- ^ a b "Teuton, n." Oxford English Dictionary. 2019.

- ^ "Teutates".

- ^ a b c Zimmer, Stefan (2005). "Teutonen". Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde. Vol. 30. De Gruyter. ISBN 3-406-33733-3.

- ^ Haubrichs, Wolfgang; Wolfram, Herwig (2005), "Theodiscus", Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde, vol. 30, De Gruyter, ISBN 3-406-33733-3

- ^ Waldman, Carl; Mason, Catherine (2006). Encyclopedia of European Peoples. Infobase Publishing. pp. 797–798. ISBN 1438129181.

The Cimbri are generally believed to have been a tribe of GERMANICS

- ^ Hussey, Joan Mervyn (1957). The Cambridge Medieval History. CUP Archive. pp. 191–193.

It was the Cimbri, along with their allies the Teutones and Ambrones, who for half a score of years kept the world in suspense. All three peoples were doubtless of Germanic stock. We may take it as established that the original home of the Cimbri was on the Jutish peninsula, that of the Teutones somewhere between the Ems and the Weser, and that of the Ambrones in the same neighbourhood, also on the North Sea coast.

- ^ See for example Pohl, Walter (2004), Die Germanen p.11: "Erst Caesar ordnete Kimbern und Teutonen den Germanen zu. Die Zeitgenossen hatten in den gefährlichen Nordbarbaren eher die direkten Nachfolger der Gallischen Invasoren um 400 v. Chr. gesehen." p. 51: "Vor Caesar hatten auch die Römer keinen umfassenden Germanenbegriff. In den älteren Quellen werden Kimbern und Teutonen nicht als Germanen bezeichnet, sondern als Kelten, Keltoskythen oder gar Kimmerier."

- ^ Strabo IV.4

- ^ Velleius Paterculus 2.12

- ^ Beck 1911, p. 673.

- ^ Pliny 4.28

- ^ Plutarch, Marius, ch. 11

- ^ Pliny the Elder 37.11. Modern analysis: Christensen, Arne Søby (2002). Cassiodorus, Jordanes and the History of the Goths. Museum Tusculanum Press. pp. 27–31. ISBN 9788772897103.; Reichert, Hermann; Timpe, Dieter (1999), "Guiones", Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde, vol. 13

- ^ Pomponius Mela (1998), Pomponius Mela's description of the world, De chorographia.English, translated by Romer, F.E., University of Michigan Press, pp. 109–117, hdl:2027/mdp.39015042048507, ISBN 978-0-472-10773-5. Comments: Christensen 2002, p. 256

- ^ Christensen 2002, p. 256.

- ^ Schütte, Gudmund (1917), Ptolemy's maps of northern Europe, a reconstruction of the prototypes, Kjøbenhavn, H. Hagerup, p. 60

- ^ Lucius Annaeus Florus, Epitome 1.38.16–17 and Valerius Maximus, Factorum et Dictorum Memorabilium 6.1.ext.3

- ^ Strauss, Barry (2009). The Spartacus War. Simon and Schuster. pp. 21–22. ISBN 978-1-4165-3205-7.

- Fick, August, Alf Torp and Hjalmar Falk: Vergleichendes Wörterbuch der Indogermanischen Sprachen. Part 3, Wortschatz der Germanischen Spracheinheit. 4. Aufl. (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht), 1909.

Attribution:

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Beck, Frederick George Meeson (1911). "Teutoni". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 26 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 673.

External links

[edit]- . . 1914. p. 1895.

Teutons

View on GrokipediaName

Etymology

The term "Teutones," referring to the ancient Germanic tribe known in English as the Teutons, derives from the Proto-Germanic noun *þeudō, meaning "people" or "tribe." The Latin form Teutones is believed to have been transmitted to Romans through Celtic intermediaries from the Proto-Germanic *Þeudanōz.[8] This root traces back to the Proto-Indo-European *tewtéh₂, denoting a "tribe" or "people," which also underlies related terms in other Indo-European languages.[1] The Proto-Germanic *þeudō further connects to Old High German *diutisc, an adjective form meaning "belonging to the people" or "popular," distinguishing the vernacular from Latin influences in early medieval contexts. This linguistic lineage influenced modern ethnonyms, including German Deutsch ("German") and English Dutch (originally referring to all "Germanic" speakers before narrowing to the Netherlands).[9] The earliest known attestations of "Teutones" appear in Greek and Latin literature from the late 2nd century BC, including accounts by authors like Posidonius of Apamea, who described the Cimbri and Teutones in the context of their migrations.[10]Historical Usage

The name "Teutons" (Greek: Τεύτονες, Latin: Teutones or Teutoni) first appears in surviving ancient sources in the context of the late second century BC migrations of northern European tribes into Roman territories. The Greek geographer Strabo, writing in the early first century CE, describes the Teutones as a Germanic people dwelling near the Cimbri in the northern regions beyond the Rhine, noting their alliance and shared customs with neighboring tribes. Roman historian Livy, in summaries of his lost books on the period, refers to the Teutones as the tribe that launched attacks on Roman camps and was subsequently defeated by consul Gaius Marius in 102 BC, using the term to denote a specific barbarian group posing an existential threat to the Republic.[11] In Roman literature, the name "Teutons" was frequently employed in propaganda to emphasize the ferocity of northern "barbarian" invaders, often paired with the Cimbri to evoke widespread panic and justify military reforms and expansions. Authors like Plutarch and later compilers such as Orosius portrayed the Teutones as a massive, warlike horde that nearly overran Gaul and Italy, with exaggerated numbers of warriors and wagons underscoring the peril to Roman civilization. This usage distinguished the Teutones from Celtic Gauls, classifying them as part of the Germanic sphere east of the Rhine, a categorization reinforced in geographical works. The Latin variant "Teutoni" appears in inscriptions and texts from the Roman era, such as military records and geographical maps, where it serves to identify the tribe or extend to broader Germanic confederations, highlighting their role in distinguishing specific invaders from other northern peoples.[12] During the medieval and Renaissance periods, the name underwent reinterpretation through renewed interest in classical texts. Tacitus' Germania (c. 98 CE), which references the Teutoni as part of the Germanic stock that had previously invaded Italy, was rediscovered in the 15th century and profoundly influenced 19th-century European nationalism, where "Teutonic" became a synonym for Germanic heritage, symbolizing ancient valor and unity among German-speaking peoples. This evolution transformed the tribal designation into a cultural emblem, detached from its original connotation of a transient threat.Linguistic and Ethnic Affiliations

Germanic Language Family

Although some ancient Roman sources classified the Teutons as Celts and a minority of modern scholars have suggested possible Celtic origins based on chieftain names, the scholarly consensus views them as a Germanic tribe whose speech belonged to the early phase of Proto-Germanic, the reconstructed ancestor language that emerged around 500 BCE and diverged into three main branches by the early Common Era: East Germanic (e.g., Gothic), North Germanic (e.g., Old Norse), and West Germanic (e.g., Old English, Old Saxon, Old High German).[13][14] This classification is supported by the scarcity of direct textual evidence but aligns with the broader linguistic profile of ancient northern European tribes documented in classical sources.[15] Scholars associate the Teutons with early Proto-Germanic, with hypothesized ties to North Germanic dialects based on proposed origins in southern Scandinavia and to West Germanic through associations with the North Sea coast and Jutland, though possible early ties to North Germanic dialects are hypothesized based on proposed origins in southern Scandinavia, where Proto-Germanic variants may have persisted before southward migrations.[15] Evidence from Roman records, including tribal designations and personal names, suggests adherence to proto-Germanic speech patterns; for instance, the ethnonym "Teutones" derives from Proto-Germanic *þeudōnōz, a plural form meaning "the people" or "the tribe," reflecting the characteristic Germanic shift in vocabulary for social units.[1] Similarly, the name of their leader Teutobod combines the Proto-Germanic element *þeudō- ("people") with a possible suffix, indicating a dialectal form consistent with early Germanic naming conventions recorded by authors like Marius and Plutarch.[1] Key distinctions from neighboring languages, such as Celtic, are evident in phonological features unique to Germanic, notably Grimm's Law—a systematic sound shift that affected stops across the branch. This law transformed Indo-European voiceless stops (*p, *t, *k) into fricatives (*f, *þ, *x) in proto-Germanic terms; for example, the root underlying "Teutones" shows *teutā (Indo-European "tribe") evolving to *þeudō with the t > þ change, a feature absent in Celtic languages that retained unshifted stops (e.g., Old Irish túath "people").[16] Such shifts, first systematically described by Jacob Grimm in 1822 based on comparative analysis of ancient and modern Germanic forms, underscore the Teutons' linguistic separation from Celtic-speaking groups in Gaul and Iberia during their migrations.[16] Hypotheses propose that remnants of the Teutonic dialect, as a proto-form within West Germanic, contributed to the development of later Low German varieties through substrate influences in northern German regions, where early tribal settlements may have left lexical and phonological traces in dialects like those of the Lower Rhine and North Sea areas.[17] These influences are inferred from shared isoglosses, such as certain vowel patterns and vocabulary for kinship and warfare, persisting in Low German despite later High German dominance, though direct attestation remains elusive due to the oral nature of pre-literate Germanic societies.[17]Relations to Other Tribes

The Teutons formed a particularly close alliance with the Cimbri, with ancient sources portraying them as kin groups originating from shared northern European territories, likely in the Jutland region or adjacent areas. Roman historians such as Plutarch describe the two tribes dividing their forces for coordinated advances during migrations, while Strabo notes their joint movements and the Cimbri's proximity to the Teutones as neighboring peoples. This partnership extended to military cooperation, where the Teutons and Cimbri supported each other in territorial expansions, reflecting ethnic affinities beyond mere temporary pacts. In contrast to other Germanic tribes, the Teutons were distinguished in Roman accounts from groups like the Suebi, who inhabited more eastern regions along the Elbe River and were characterized by unique cultural practices such as the Suebian knot hairstyle, as detailed by Tacitus. The Suebi represented a larger confederation of Irminonic tribes, separate from the northern, possibly Ingvaeonic Teutons, with no recorded direct interactions or overlaps in ancient sources. Similarly, the Ambrones, frequently mentioned alongside the Teutons, appear as a distinct entity; their origins are debated, with possibilities of Celtic ties to Helvetia or Noricum or Germanic links to the North Sea region, setting them apart from the Teutonic core despite shared migratory paths.[18] During their southward movements, the Teutons encountered and interacted with Celtic tribes in Gaul and the Alps, leading to potential conflicts over resources as well as opportunistic mergers for mutual benefit. Sources like Orosius and later interpretations of Roman records indicate alliances with Celtic groups such as the Tigurini, where the Teutons joined forces to navigate hostile territories, though tensions arose from competing claims to land. These interactions highlight the Teutons' adaptability in forming hybrid coalitions amid ethnic boundaries, occasionally absorbing Celtic elements into their migrating bands.[19] Historians have theorized that the Teutons participated in a larger "Cimbric-Teutonic" confederation encompassing the Cimbri, Ambrones, and other northern peoples, functioning as a loose ethnic alliance driven by environmental pressures and expansionist goals. This view, supported by analyses of ancient testimonies from Posidonius via Strabo, posits the confederation as a multi-tribal entity blending Germanic leadership with diverse subordinate groups, including possible Celtic fringes, to amplify their collective strength. Such structures were common among prehistoric migrations, allowing the Teutons to project influence far beyond their original kin networks.[20]Homeland and Origins

Proposed Locations

The primary theory regarding the Teutons' homeland locates them on the Jutland Peninsula, encompassing parts of modern-day Denmark and northern Germany, often in association with the neighboring Cimbri tribe. This placement draws from ancient Roman and Greek accounts that describe the Teutons as originating from the northern Germanic regions near the North Sea. However, Claudius Ptolemy's Geography (2nd century AD), in Book II, Chapter 11, section 17, positions the Teutones further east in the interior of Germania, near the Suebi and away from the Cimbri, whom he places in the Jutland area (Cimbric Peninsula).[20] This discrepancy has led scholars to question whether Ptolemy's coordinates reflect post-migration settlements or earlier ethnographic data derived from earlier sources like Marinus of Tyre.[21] Alternative hypotheses propose origins in broader southern Scandinavia or along the Baltic coasts, potentially extending into modern-day southern Sweden or the eastern shores of the Jutland region. These theories link the Teutons to environmental pressures, including sea-level rise and coastal inundations around 120–110 BC, which may have displaced northern Germanic groups southward. Alternative environmental explanations include long-term soil degradation in the Northwest European Plain's sandy landscapes, resulting from intensive Celtic field agriculture and population growth, which caused societal stress and prompted migration, as proposed in recent studies.[3] Such events are inferred from geological evidence of storm surges and tidal flooding in the region during the late Bronze Age transition to Iron Age.[22] Ancient Roman accounts, particularly those attributed to the Stoic philosopher Posidonius of Rhodes (1st century BC), attribute the Teutons' and Cimbri's migrations to a combination of overpopulation, cold climate deterioration, and catastrophic sea flooding that submerged their coastal homelands. Posidonius, as reported in fragments preserved by later authors like Strabo and via intermediaries such as Verrius Flaccus and Florus, described how the tribes fled inundated lands, interpreting the event as a natural disaster forcing mass exodus.[21] These narratives emphasize ecological and demographic drivers over purely aggressive expansion. Criticisms of these theories highlight the absence of direct textual or material evidence explicitly identifying the Teutons with specific Jutland or Baltic sites, relying instead on indirect associations with the Cimbri. Ptolemy's eastern placement for the Teutones lacks corroboration from contemporary sources like Pliny the Elder or Tacitus, who vaguely situate them in northern Germania without precise coordinates, suggesting possible confusion between the tribe's origin and later wanderings. Similarly, the sea-level rise hypothesis, while supported by paleoclimatic data for the North Sea region, cannot definitively tie inundation events to the Teutons, as no ancient inscription or artifact names them in situ. Posidonius' flood account, preserved only in secondary fragments, may reflect Roman sensationalism rather than eyewitness ethnography, with modern analyses debating whether it describes a tsunami, storm surge, or exceptional tides.[20] Overall, these proposals remain speculative, informed more by linguistic ties to proto-Germanic northern origins than conclusive geographic proof.[22]Archaeological Evidence

The Jastorf culture, spanning approximately 600 BC to 1 BC, represents a key archaeological complex linked to the early Germanic peoples, potentially including tribes like the Teutons, primarily in northern Germany and extending into southern Scandinavia.[23] This culture marks the transition to the Iron Age in the region, with settlements featuring longhouses and evidence of agriculture, animal husbandry, and ironworking.[24] Characteristic of the Jastorf culture are extensive urnfield cemeteries, where cremated remains were interred in pottery urns arranged in organized fields, often accompanied by grave goods such as iron tools, fibulae, and weapons.[25] Iron implements, including sickles, knives, and axes, indicate advancements in metallurgy and daily life, reflecting a society increasingly reliant on iron for both practical and ritual purposes.[26] Artifacts from migration-era sites associated with Teutonic cultural spheres include iron swords and jewelry bearing early Germanic motifs, such as animal-style ornamentation and geometric patterns, found in burials and hoards across northern Europe. These items, often deposited in wetlands or graves, suggest warrior elites and trade networks, though direct attribution to the Teutons remains inferential due to the absence of tribe-specific inscriptions or runic markings.[27] Correlations to Teutonic material culture are drawn from bog bodies and hillforts in Denmark, where well-preserved Iron Age human remains, dating to the 4th–1st centuries BC, exhibit signs of ritual sacrifice consistent with Germanic practices described in later Roman accounts.[28] Hillforts, such as those in Jutland—proposed as a Teutonic homeland—reveal fortified enclosures with iron artifacts and pottery akin to Jastorf styles, indicating defensive communities during periods of mobility.[29] Modern excavations, particularly 20th-century digs in Schleswig-Holstein, have uncovered settlements and burials consistent with early Germanic material culture in the region proposed as the Teutonic homeland, including iron tools and urns from Jastorf-phase sites like those near the Elbe River.[30] These findings, analyzed through radiocarbon dating and artifact typology, reinforce the cultural continuity of pre-Roman Germanic groups in the region.[31]Migrations and Conflicts

Early Migrations

The Teutons, a Germanic tribe from the Jutland peninsula, commenced their southward migration around 120 BC alongside allied groups like the Cimbri, driven primarily by environmental catastrophes such as severe flooding and subsequent soil degradation that rendered their homeland untenable.[3] These pressures compelled the population to seek higher ground and ultimately new territories. The migration encompassed a vast multitude, with Roman accounts estimating the Teutons alone at approximately 300,000 individuals, including combatants, non-combatants, families, and supply wagons, while the combined forces with the Cimbri may have approached 500,000 in total.[32] This scale reflected not merely a military expedition but a full societal relocation, burdened by the necessities of sustaining an entire people on the move.[5] Traveling as a cohesive migratory body, the Teutons progressed eastward from Jutland before turning south, fording the Rhine River into the Gaulish territories around 113–111 BC, where they traversed the lands of the Celtic Helvetii and engaged in interactions that included recruitment of local elements like the Tigurini subgroup.[33][34] Their path through Gaul followed river valleys such as the Rhône, aiming toward more arable southern regions suitable for agriculture and settlement.[35] Contemporary observers, including those reporting on Gaius Marius's campaigns, attributed the Teutons' drive to an urgent quest for fertile farmland amid the hardships of their northern origins, underscoring the migration as a desperate bid for survival rather than conquest.[3][5]The Cimbrian War

The Cimbrian War, spanning from 113 to 101 BC, was a protracted conflict between the Roman Republic and migrating Germanic tribes, including the Teutons and Cimbri, initiated by the tribes' incursions into the Roman-allied kingdom of Noricum and subsequent advances into Gaul.[36] The Teutons, allied closely with the Cimbri in a loose confederation of Germanic groups, played a pivotal role as a formidable contingent within this migratory force, contributing to coordinated movements that pressured Roman frontiers.[37] The Teutons and Cimbri conducted joint raids across Gaul, devastating settlements and Roman interests, with their forces defeating the Romans at the Battle of Arausio (modern Orange) in 105 BC during a major confrontation that highlighted their combined raiding prowess.[38] These actions exemplified the Teutons' involvement in the broader tribal offensives, where they operated alongside the Cimbri to exploit vulnerabilities in Roman provincial defenses.[5] Roman forces encountered severe setbacks early in the war, including a disastrous defeat at Noreia in 113 BC, where consul Gnaeus Papirius Carbo's army was ambushed and routed by the Cimbri and their allies, including Teutonic elements.[37] The catastrophe at Arausio further compounded these losses, resulting in the annihilation of up to 80,000 Roman troops and sparking widespread panic in Italy over the potential invasion of the peninsula by these barbarian hordes.[39] In 102 BC, under their king Teutobod, the Teutons advanced through southern Gaul toward the Alps but were intercepted by Gaius Marius near Aquae Sextiae (modern Aix-en-Provence). In the Battle of Aquae Sextiae, Roman forces ambushed and annihilated the Teutonic army, capturing Teutobod and killing or enslaving tens of thousands, effectively ending the Teutons' threat.[2] Strategically, the Teutons functioned as a highly mobile striking force within the tribal coalition, their nomadic warfare style enabling rapid advances that threatened key Roman provinces in Gaul and along the Alpine approaches, forcing Rome to divert significant resources to counter the existential peril.[5]Aftermath and Legacy

Defeat by Rome

Gaius Marius emerged as the key Roman leader against the Teutonic migrations, leveraging his multiple consulships from 107 BC onward to enact transformative military reforms. Elected consul in 107 BC despite lacking senatorial prestige, Marius assumed command in Numidia before turning to the northern threat, securing re-elections in 104, 103, and 102 BC to maintain uninterrupted authority over the legions.[40] These extended terms, unprecedented at the time, allowed him to address the crisis systematically.[41] Marius' reforms professionalized the Roman army by recruiting from the capite censi—the propertyless poor—transforming it into a volunteer force paid by the state and equipped uniformly, including standardized gear carried by each soldier.[42] He emphasized intensive training in marching, entrenchment, and weapons handling, fostering a disciplined force capable of sustained campaigning.[40] These changes shifted loyalty from the state to individual commanders like Marius himself, enhancing cohesion against irregular tribal warriors.[41] In 102 BC, Marius positioned his army near Aquae Sextiae (modern Aix-en-Provence) to intercept the Teutons and their allies, the Ambrones, as they sought passage through Gaul toward Italy. The Romans repelled initial assaults and executed a decisive ambush, annihilating the tribal forces in a battle fought over several days.[43] Caught between the Atax River and Marius' legions, the Teutons formed a defensive wagon laager, but Roman cohorts—flexible tactical units of about 480 men—maneuvered swiftly to envelop and breach it. Legionaries scaled the wagons under pilum volleys, engaging in brutal close combat that slaughtered warriors, women, and children alike.[44] This innovative use of cohorts allowed for rapid redeployment and concentrated assaults, overwhelming the disorganized tribal defenses.[42] Roman accounts report staggering Teutonic losses at Aquae Sextiae, with Orosius estimating 200,000 killed and 80,000 captured among the Teutons and Ambrones combined. King Teutobod was captured by Marius, marking the effective end of the Teutonic military capacity.[45] Survivors were largely enslaved and integrated into Roman society, with many women and children sold into servitude, contributing to the labor force in Italy and provinces. The subsequent Battle of Vercellae in 101 BC sealed the broader campaign, as Marius allied with consul Quintus Lutatius Catulus to confront the related Cimbri tribe. Roman forces enveloped the Cimbri through coordinated cavalry flanks and infantry pressure, annihilating their host in an envelopment maneuver that echoed tactics refined against the Teutons.[43] This victory eliminated the remaining Germanic threat from the migrations.[45] Marius' triumphs led to multiple triumphs in Rome, bolstering his political influence and prompting further militarization of the Republic, including strengthened defenses along the Rhine and Alps.Cultural and Historical Impact

In Roman historiography, the Teutons were frequently depicted as embodiments of barbarism and uncontrollable ferocity, serving as cautionary symbols against the threats posed by northern invaders to Roman civilization. Plutarch, in his Life of Marius, describes the Teutons as exceptionally tall and robust warriors with fair skin, blue eyes, and a wild, untamed appearance, emphasizing their women's equal stature and the tribe's collective rage in battle, which nearly overwhelmed Roman forces before Marius' victory at Aquae Sextiae in 102 BCE.[46] Similarly, Florus in his Epitome of Roman History portrays the Teutons as nomadic fugitives from flooded lands who ravaged the Roman province of Gaul, defeating consuls Caepio and Mallius through sheer numbers and savagery, only to be crushed by Marius, thereby reinforcing the narrative of Roman resilience against primal chaos. These accounts contributed to the enduring trope of furor Teutonicus, a Latin phrase encapsulating the perceived Germanic fury and irrational violence, as analyzed in Christine Trzaska-Richter's study of Roman propaganda, which traces its origins to the Cimbrian War encounters and its use in political rhetoric to justify imperial expansion. During the 19th-century Romantic era, the Teutons were romanticized in German nationalism as ancestral heroes embodying a pure, primordial Germanic spirit, distinct from Roman or French influences. Intellectuals and historians, drawing on Tacitus' Germania and medieval sagas, invoked the Teutons as symbols of unyielding freedom and cultural vitality, fueling the push for unification amid the Napoleonic aftermath.[47] This "Teutonic heritage" manifested in literature and music, notably Richard Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen, where Norse-Germanic myths—reimagined as Teutonic epics—celebrated heroic individualism and mythic landscapes, aligning with nationalists' vision of a reborn German Volk.[48] Wagner's tetralogy, premiered in 1876, blended ancient tribal lore with Romantic ideals, portraying gods and warriors in a pre-Christian idyll that resonated with pan-Germanic aspirations, though it idealized rather than historically accurate depictions of tribes like the Teutons. Archaeologically, the Teutons' legacy has shaped interpretations of the Germanic Migration Period (ca. 300–700 CE), linking them to the proto-Germanic Jastorf culture (6th–1st centuries BCE) in northern Germany and Jutland, where iron tools, urn burials, and fortified settlements indicate early tribal formations preceding the Cimbrian migrations. This association has influenced scholarly models of ethnogenesis and mobility, as explored in Ian Wood's analysis of post-Roman historiography, which uses Teutonic artifacts and Roman reports to reconstruct broader patterns of Germanic expansion and cultural continuity across Europe.[49] Such studies emphasize interdisciplinary evidence—from linguistics to isotope analysis—revealing the Teutons not as isolated barbarians but as integral to the dynamic networks that transformed late antique societies. In the 20th century, the Teutons were misappropriated by Nazi ideology to propagate Aryan supremacy, recasting them as archetypal Nordic conquerors whose "blood and soil" (Blut und Boden) justified expansionism and racial purity doctrines. Propagandists like Richard Walther Darré invoked the Teutons' supposed invasion of Rome as proof of Germanic destiny to dominate "degenerate" cultures, integrating them into a fabricated narrative of eternal Teutonic vigor.[50] This distortion ignored historical complexities, such as the Teutons' likely Celtic-Germanic hybridity and defeat's dispersal. Scholarly critiques, including those in post-war analyses of völkisch thought, contrast this with evidence-based views, highlighting how Nazi rhetoric weaponized Romantic nationalism while overlooking the tribes' integration into Roman provinces and their limited direct lineage to modern Germans.[51]References

- https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/Teuton