Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Semnones

View on Wikipedia

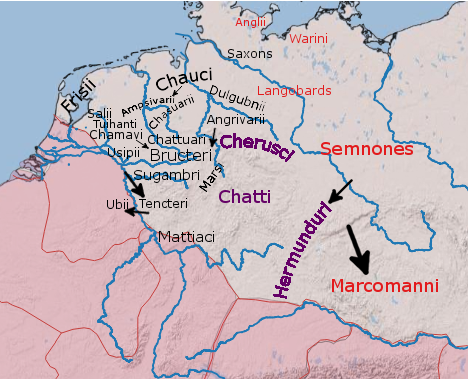

The Semnones were a Germanic people, and more specifically a Suebi people, who lived near the Elbe river in the 1st and 2nd centuries AD, during the time of the Roman empire.

The 2nd century geographer Claudius Ptolemy places the Semnones between the Elbe and "Suebos" river. Modern scholars believe that the Suebos was the Oder. However, archaeological evidence suggests they stretched as far as the Spree and Havel rivers in the east, and not quite as far as the Oder. To their north was another part of the Havel, and to the south the Fläming Heath. In present day terms they were therefore in the area between the modern cities of Magdeburg and Berlin.[1]

During the reign of Augustus (63 BC - 14 AD), Velleius Paterculus reported that the future emperor Tiberius reached the Elbe river which flows through the lands of the Semnones and Hermunduri.[2] The Res Gestae Divi Augusti reports that Augustus extended the Roman boundaries to the Elbe river and that after he sailed a fleet to present day Denmark, the Cimbri, Charydes and Semnones along with other Germanic peoples of that same region "through their envoys sought my friendship and that of the Roman people".[3]

They were described in the late 1st century by Tacitus in his Germania:

"The Semnones give themselves out to be the most ancient and renowned branch of the Suebi. Their antiquity is strongly attested by their religion. At a stated period, all the tribes of the same group assemble by their representatives in a grove consecrated by the auguries of their forefathers, and by immemorial associations of terror. Here, having publicly slaughtered a human victim, they celebrate the horrible beginning of their barbarous rite. Reverence also in other ways is paid to the grove. No one enters it except bound with a chain, as an inferior acknowledging the might of the local divinity. If he chance to fall, it is not lawful for him to be lifted up, or to rise to his feet; he must crawl out along the ground. All this superstition implies the belief that from this spot the nation took its origin, that here dwells the supreme and all-ruling deity, to whom all else is subject and obedient. The fortunate lot of the Semnones strengthens this belief; a hundred cantons are in their occupation, and the vastness of their community makes them regard themselves as the head of the Suebic tribe."[4]

The Semnones's own name is apparently etymologically similar or even the same as the one recorded by Roman authors as "Suebi" and during his own time Julius Caesar, had mentioned Suebi but not Semnones, being a powerful tribal group with 100 cantons.

The king of the Semnones Masyas and his priestess Ganna are mentioned by Cassius Dio. They worshipped a supreme god (Latin: regnator omnium deus) at a sacred grove. A grove of fetters is also mentioned in the eddic poem Helgakviða Hundingsbana II. Ptolemy's map of Germania mentions a forest called Semanus Silva, but a relation to the Semnones is unknown.

In the 3rd century, the Semnones shifted southwards and eventually ended up as part of the Alemanni people.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Castritius 2005.

- ^ Castritius 2005 citing Velleius 2.106

- ^ Castritius 2005 citing Res Gestae,26

- ^ Tacitus, Germania, Germania.XXXIX

Sources

[edit]- Castritius, Helmut (2005), "Semnonen § 2. Historisch", in Beck, Heinrich; Geuenich, Dieter; Steuer, Heiko (eds.), Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde, vol. 28 (2 ed.), De Gruyter, ISBN 978-3-11-018207-1

- Sitzmann, Alexander (2005), "Semnonen § 1. Namenkundlich", in Beck, Heinrich; Geuenich, Dieter; Steuer, Heiko (eds.), Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde, vol. 28 (2 ed.), De Gruyter, ISBN 978-3-11-018207-1