Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

The Barricades

View on Wikipedia| The Barricades | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Revolutions of 1989, Singing Revolution and Dissolution of the Soviet Union | |||||||

Barricade in Jēkaba Street, July 1991 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

2 policemen killed 4 civilians killed 4 policemen wounded 10 civilians wounded[nb 1] | At least 1 OMON soldier killed[1] | ||||||

| |||||||

| Eastern Bloc |

|---|

|

The Barricades (Latvian: Barikādes) were a series of confrontations between the Republic of Latvia and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics in January 1991 which took place mainly in Riga. The events are named for the popular effort of building and protecting barricades from 13 January until about 27 January. Latvia, which had declared restoration of independence from the Soviet Union a year earlier, anticipated that the Soviet Union might attempt to regain control over the country by force.

After attacks by the Soviet OMON on Riga in early January, the government called on people to build barricades for protection of possible targets (mainly in the capital city of Riga and nearby Ulbroka, as well as Kuldīga and Liepāja). Six people were killed in further attacks, several were wounded in shootings or beaten by OMON. Most victims were shot during the Soviet attack on the Latvian Ministry of the Interior on January 20, while another person died in a building accident reinforcing the barricades. The exact number of casualties among the Soviet loyalists is unknown. Around 32,000 people have received Commemorative Medal for Participants of the Barricades of 1991 for the participation or support for the event.[2]

Background

[edit]During World War II Latvia had been occupied by USSR twice (1940/41 and in July 1944. In 1985, Mikhail Gorbachev introduced glasnost and perestroika policies, hoping to salvage the failing Soviet economy. The reforms also lessened restrictions on political freedom in the Soviet Union. This led to unintended consequences as problems within the Soviet Union and crimes of the Soviet regime, previously kept secret and denied by the government, were exposed, causing public dissatisfaction, further deepened by the war in Afghanistan and the Chernobyl disaster starting in April 1986. Another unintended consequence of Glasnost for the Soviet central authorities was the long-suppressed national sentiments that were released in the republics of the Soviet Union.

Massive demonstrations against the Soviet regime began. In Latvia an independence movement started. The supporters of independence – the Popular Front of Latvia, the Latvian Green Party and the Latvian National Independence Movement – won elections to the Supreme Soviet of the Latvian SSR, on 18 March 1990 and formed the Popular Front of Latvia faction, leaving the pro-Soviet Equal Rights faction in opposition.

On 4 May 1990, the Supreme Soviet, which afterwards became known as the Supreme Council of the Republic of Latvia, declared the restoration of independence of Latvia and began secession from the Soviet Union. The USSR did not recognize these actions and considered them contrary to the Soviet federal and republican constitutions. Consequently, the tension in relations between Latvia and the Soviet Union and between the independence movement and pro-Soviet forces, such as the International Front of the Working People of Latvia (Interfront) and the Communist Party of Latvia, along with its All-Latvian Public Rescue Committee, grew.

Soviet military crackdown threat

[edit]The pro-Soviet forces tried to provoke violence and seize power in Latvia. A series of bombings occurred in December 1990, Marshal of the Soviet Union Dmitry Yazov admitted that the military was responsible for the first four bombings, perpetrators of the other bombings remain unknown, the pro-Communist press of the time blamed Latvian nationalists.

The government of the Soviet Union and other pro-Soviet groups threatened that a state of emergency would be established which would grant unlimited authority in Latvia to President Gorbachev and military force would be used to "implement order in the Baltic Republics". At the time Soviet troops, OMON units and KGB forces were stationed in Latvia. On 23 December 1990 a large combat group of KGB was exposed in Jūrmala. It was rumored at the time that there would be a coup and a dictatorship would be established. Foreign minister of the Soviet Union Eduard Shevardnadze seemingly confirmed this when he resigned on 20 December 1990, stating that a dictatorship was coming.[3]

On 11 December 1990, the Popular Front released an announcement stating that there was no need for a climate of fear and hysteria in what was dubbed hour X – the unlimited authority of the president – would come and every person should be ready to consider what they would do if that happened. The Popular Front also made suggestions regarding what should be done until hour X and afterwards, if Soviet forces were successful. These plans called for acts to show support for independence and attract the attention of international society, joining volunteer guard units, reasoning with Russians in Latvia explaining to them, especially military officers, that the ideas of the Popular Front are similar to those of Russian democrats. It also called for an effort to protect the economy and ensure information circulation should also be made.[4]

In case of Soviet control being successfully established, this plan called for a campaign of civil disobedience – ignoring any orders and requests of the Soviet authorities, as well as any Soviet elections and referendums, undermining the Soviet economy by going on strike and by following the absurdly elaborate Soviet manufacturing instructions to the letter in order to paralyze production, helping the independence movement to continue its work illegally and helping its supporters to get involved in the work of the Soviet institutions. Finally, carefully documenting any crimes Soviet forces might commit during the state of emergency.[4]

Attacks in early January

[edit]

On 2 January 1991 the OMON seized the Preses Nams (English: Press House), the national printing house of Latvia and attacked criminal police officers who were documenting the event.[5] The Supreme Council held a session in which it was reported that the manager of the Preses Nams was being held hostage, while other workers, although physically and verbally abused, were apparently allowed to leave the printing house. The Supreme Council officially recognized the taking of the printing house as an illegal act on the part of the Communist Party of Latvia.[6]

The Popular Front organised protests at the Communist Party building.[5] The printing house was partly paralysed as it continued to print only pro-Soviet press.[7] On 4 January the OMON seized the telephone exchange in Vecmīlgrāvis, it is speculated that it was because the telephone lines the OMON were using were cut off. Thereafter, the OMON seized the Ministry of Internal Affairs but the phone wasn't cut off for fear that the OMON would attack the international telephone exchange.[8] Contrary to OMON officer claims Boris Karlovich Pugo and Mikhail Gorbachev both claimed they were not informed of this attack. Meanwhile, the Soviet military was on the move – that same day an intelligence unit arrived in Riga.

Then on 7 January, following the orders of Mikhail Gorbachev, Dmitriy Yazov sent commando units into several Republics of the Soviet Union including Latvia.

On 11 January, the Military Council of the Baltic Military District was held. It decided to arm Soviet officers and cadets with machine guns. Open movement of Soviet troops and armored vehicles were seen in the streets of Riga.[5] Several meetings by both pro-independence and pro-Soviet movements were held on 10 January. Interfront held a meeting calling on the government of Latvia to resign. Some 50,000 people participated and tried to break into the Cabinet of Ministers building after being asked to do so by military personnel.[5]

Construction of the Barricades

[edit]

On 11 January, the Soviet military launched an attack on Latvia's neighbour, Lithuania.

On 12 January, the Popular Front announced nationwide demonstrations to be held on 13 January in support of Latvia's lawfully elected government and the guarding of strategic objectives. The Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the Russian SFSR called on the Soviet government to withdraw its military forces from the Baltic States. Leaders of the Latvian government met with Gorbachev who gave assurances that force would not be used. That night the Popular Front, after learning that Soviet forces in Lithuania had attacked the Vilnius TV Tower and killed 13 civilians, called on people to gather for the defense of strategic objectives.[5] Due to a united effort of the Baltic states to regain their independence in the previous years of the singing revolution, an attack on one of them was perceived as an attack on all of them.[9]

At 4:45 on 13 January, an announcement from the Popular Front was broadcast by Latvian radio calling people to gather in Riga Cathedral square. At 12:00 noon the Supreme Council session on defense issues was held. At 14.00 the Popular Front's demonstration began, around 700,000 people had gathered, Soviet helicopters dropped leaflets with warnings over the crowd at this point. The Popular Front called on people to build barricades. The Supreme Council held another session after the demonstration, the Members of Parliament (MPs) were asked to stay at the Supreme Council overnight. The evening session issued a call for Soviet soldiers asking them to disobey orders concerning the use of force against civilians.[10] As night came, following orders from the government, agricultural and construction machines and trucks full of logs arrived in Riga to build barricades. Trucks, engineering vehicles and agricultural machinery were brought into the city to block streets. People had already been gathering during the day. Part of this crowd gathered in Riga Cathedral Square as the Popular Front had asked in its morning announcement. Others gathered after the midday demonstration. They included colleagues and students. Some were organised by their employers and alma maters. Many families arrived, including women, the elderly and children. By that time most were already morally prepared that something could happen. People had arrived from all over the country. Barricades were largely perceived as a form of nonviolent resistance, people being ready to form a human shield. However, many people did arm themselves, using whatever was available, ranging from pieces of metal to specially crafted shields and civil defence supplies. Some had also prepared Molotov cocktails, but these were confiscated to ensure fire safety. The Latvian militia was armed with sub-machine guns and handguns.

The Latvian government was later criticized for not providing weapons. These they had, as was evidenced after the OMON seized the Ministry of Interior and removed a considerable number of weapons (it was asserted that there were 200 firearms in the ministry)

Trucks were loaded with construction and demolition waste, logs and other cargo. Large concrete blocks, walls, wire obstacles and other materials were also used. The building work began on the evening of 13 January and took about three hours. The main objects of strategic interest were the Supreme Council buildings (Old town near St. James's Cathedral), the Council of Ministers (city center near the Nativity of Christ Cathedral), Latvian Television (on Zaķusala), Latvian Radio (Old town near Riga Cathedral), the international telephone exchange offices (city center), Ulbroka radio and bridges. Barricades were also built in other parts of the country, including in Liepāja and Kuldīga.

Care was taken to record the events, not only for accounting purposes and personal keepsakes but also to show the world what was happening. About 300 foreign journalists worked in Riga at the time.[11] The Latvian government ensured that the foreign press was provided with constant updates.

Many strategic objects were important mainly for the transfer of information. This would ensure that if the Soviets did launch an attack, the Latvian forces could hold these locations long enough to inform the rest of the world. The international telephone exchange was important to maintain connections with both foreign countries and other parts of the USSR. An often-noted example is Lithuania. It was partly cut off from the rest of the world after the Soviet attack. Foreign calls to Lithuania were transferred through Riga. Latvian radio and television worked day and night to broadcast throughout the time of the barricades.

The radio played an important part in life on the barricades. It was used to organize eating and sleeping arrangements, calling people together (e.g. students from the same university), for the various meetings. Artists were invited to entertain people. Foresters were asked to provide firewood for the bonfires that were widely used by the people manning the barricades. Food and drink were provided by a number of public institutions. Many well-wishers provided knit socks and gloves as well as refreshments. Places to sleep were often hard to find - schools were used where possible. Many people either slept at the barricades or went home. Some people experienced an exacerbation of their health problems which was not helped by the winter climate, exhaustion and stress.[8]

First aid points were set up with additional medical supplies and equipment, some were based on existing locations. Beds were installed in a number and had teams composed of doctors from local hospitals. Shifts were formed by daily routine - people who went to their job, studies or home were replaced by people who returned to the barricades after their daily duties. Most workers who had been on the barricades later received their usual salary regardless of if they had or had not been to work. Prime minister Ivars Godmanis regularly held meetings with commanders of individual barricades, the Popular Front also participated to discuss tactics. It was decided to enforce protection of the most important objectives by assigning militia to their defense. The supplies for the barricades were coordinated by the Popular Front. The individual barricades were organised by regions. Thus, people from Vidzeme were assigned to barricades overseen by the Vidzeme suburb chapter of the Popular Front. The pro-Soviet forces tried to infiltrate barricades for sabotage. Rumors were spread that attacks were planned.[8]

Fighting

[edit]On 14 January, the Commander of the Soviet army in the Baltic Military District Fyodor Kuzmin issued an ultimatum against the Supreme Council of the Republic of Latvia chairman Anatolijs Gorbunovs, demanding that the adopted laws are repealed.[12] The OMON attacked Brasa and Vecmilgrāvis bridges. 17 cars were burned during the day. On the night of 15 January, the OMON twice attacked the Riga branch of the Minsk Militia Academy. Later that day 10,000 people gathered for an Interfront meeting, where an All-Latvian Public Rescue Committee declared that it was taking over power in Latvia. This announcement was broadcast in the Soviet media.

On 16 January, the Supreme Council organised MPs to stay overnight at the Supreme Council building to ensure a quorum in case of need. At 4:45 pm, in another attack on Vecmilgrāvis bridge, a driver for the Latvian Ministry of Transport, Roberts Mūrnieks was shot in the back of the head with an automatic weapon and died from the injury at the Riga Hospital No. 1 intensive care unit at 6:50 pm, becoming the first fatality at the barricades.[13] Two other people were also injured. At 6:30 pm the OMON attacked Brasa bridge, injuring one person. Another bombing took place at 8:45 pm.[8]

On 17 January, the alarm was sounded at the Barricades, the strike committee of the Communist Party of Latvia declared that fascism was being reborn in Latvia. A delegation of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR visited Riga. Upon its return to Moscow, the delegation reported that Latvia was in favour of the establishment of unlimited authority of the USSR president.

On 18 January the Supreme Soviet decided to form a national self-defense committee. The Popular Front withdrew its call to protect the barricades.

On 19 January, the funeral of Roberts Mūrnieks turned into a demonstration. That night the OMON arrested and beat up five members of a volunteer guard unit.[14]

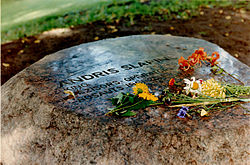

On 20 January, about 100,000 people gathered in Moscow to show their support for the Baltic states, calling on Soviet officials to resign in connection with the events in Vilnius. That evening turned out to be the deadliest at the Barricades after the OMON and other unidentified combat groups attacked the Latvian Interior Ministry. Two policemen (Vladimirs Gomanovičs and Sergejs Konoņenko), camera operator and director Andris Slapiņš and 17-year-old schoolboy Edijs Riekstiņš were killed.[15] Gvido Zvaigzne was fatally injured and died of his injuries on 5 February.[12] Four Bauska policemen were injured, as were five participants of the barricades, a Hungarian János Tódor, Finnish journalist and TV operator Hannu Väisänen and Russian camera operator for the TV program Vzglyad Vladimir Brezhnev.[15] It was noted that the attackers also suffered casualties. After the battle, the OMON moved into the Latvian Communist Party building. By the 20 January, the government also urged the transfer of control of the barricades to government forces. This was seen by some as disaffection with the whole idea. This opinion was enforced when part of the barricades were demolished after the government took control of them.

On 21 January, the Supreme Council called on youths to apply for a job in the Interior ministry system. Gorbunovs left for Moscow to meet with Gorbachev to discuss the situation in Latvia. On 22 January, Pugo denied he had ordered an attack on the interior ministry.[12] Another person was killed on the barricades.

On 24 January, the Council of Ministers established a public safety department to guard the barricades.

On 25 January, after the funeral of the 20 January victims, defenders of the barricades left.[12]

Aftermath and further developments

[edit]

The actual barricades remained on the streets of Riga for a long time; for example, those at the Supreme Council were removed only in the autumn of 1992.[8] In March partially in response to January events and partially because of upcoming Soviet referendum on preservation of federation, which Latvia intended to boycott, a poll on independence was held with three-quarters of participants voting in favor of independence. Latvia faced further attacks of Pro-Soviet forces later in 1991 – on 23 May, when OMON launched attack on five Latvian border posts and during the Soviet coup attempt of 1991, when several strategic objectives guarded during the barricades were seized, with one civilian (driver Raimonds Salmiņš) killed by Soviet forces. The attempted coup prompted the Latvian government, which originally had intended gradual secession from the Soviet Union to declare full independence, which was recognized by the Soviet Union on 6 September. The Soviet Union was dissolved in December 1991.

Responsibility

[edit]Major attacks were carried out by the OMON of Riga, however, another combat unit was seen during the attack on the Ministry of Interior Affairs. It has been speculated that this unit was Alpha Group which had been seen in action during the attack on Vilnius.[11] In an interview with film director Juris Podnieks, an OMON officer stated that originally it was planned to attack Riga, not Vilnius. At the last moment, a week before the attack on Vilnius, the plan was suddenly changed. He also claimed that the OMON of Rīga was so well prepared that there was no need for the Soviet military, which was present in Rīga at the time, to engage.[16]

The OMON did not act on their own – after the Preses Nams was seized the OMON claimed that high officials of the Soviet government – Boris Pugo and Mikhail Gorbachev knew about the attack, however, both denied their involvement and the Supreme Council blamed the Communist Party of Latvia. In December before the events, the Popular Front, in its instructions for X hour, asserted that a coup was planned by the "Soyuz" group of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR MPs.[4]

Dimitry Yuzhkov admitted that the Soviet military was responsible for the first bombings, however, no one claimed responsibility for the rest of the bombings, which the communist press blamed on Latvian nationalists.[5] On the basis of these and subsequent events, several OMON officers were tried, although many of them were not convicted, the Communist Party of Latvia, Interfront, the All-Latvian Public Rescue Committee and a few related organizations were banned by parliament for the attempted coup d'état, and two leaders of CPL and ALPRC were tried for treason.[17] [18] On 9 November 1999, the Riga District Court found ten former Riga OMON officers guilty for their involvement in the attacks.[19]

Viktor Alksnis transplanted a large number of the Baltic OMON forces to the Transnistrian territory of Moldova in support of the separatist regime there, where Vladimir Antyufeyev, commander of the Riga OMON forces, took on the role of Minister of Security initially under an assumed name (Vladimir Shevstov), a post he held until 2012. Antyufeyev appeared in Ukraine as the "deputy prime minister" of the Russian-backed Donetsk People's Republic in July 2014.[20]

Nonviolent resistance

[edit]The Barricades was a nonviolent resistance movement as the participants were publicly encouraged not to carry any weapons despite the Soviet Union taking brutal measures against protesters.

The Popular Front of Latvia developed a plan, called “Instructions for X-hour”, which was published in the press in December 1990. It set out what actions should be taken by the general public in case of an act of aggression and hostility from the Soviet Union. It stated that all protest must be nonviolent and everything must be documented with photos and videos so there would be evidence to counter possible Kremlin propaganda.[2]

Notwithstanding Mikhail Gorbachev's promises not to use violent methods to change power in the Baltic states, the USSR army and the interior structures attacked local authorities and strategic sites in Lithuania and Latvia in January 1991 killing officers and civilians.[21]

Legacy

[edit]

In 1995, a support fund for 'Participants of the Barricades of 1991' was created. The fund is for the families of victims. It also gathers information on participants.[22] In 2001 the fund created the 'Museum of the Barricades of 1991' to make historical materials it had gathered available to the public.[23]

20 January is the commemoration day of Participants of the Barricades, they are remembered on this day as well as on 18 November, 4 May and 21 August. Participants of the barricades are awarded the Commemorative Medal for Participants of the Barricades of 1991. This award was established by the fund of 'Participants of the Barricades of 1991' in 1996. Since 1999 it is awarded by the state for those who had shown courage and unselfishness during the Barricades.[24][25] The Barricades are also commemorated by numerous monuments in Latvia.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Mirlins 2016, p. 249

- ^ a b Zaltāns, Kaspars (March 8, 2016). "Latvia's Barricades of Freedom – What Do They Mean 25 Years On?". Deep Baltic. Retrieved February 6, 2018.

- ^ Dainis Īvāns (13 January 1991). "Morning session of Supreme council on 13 January 1991" (in Latvian). Archived from the original on 4 May 2019. Retrieved 2007-08-13.

(Enquired what indicates that military dictatorship is starting) Pirmkārt, mēs visi ļoti labi atceramies Eduarda Ševardnadzes uzstāšanos Tautas deputātu kongresā un viņa brīdinājumu (English: First of all we all remember very well Eduard Shevardnadze's address to the Congress of Soviets and his warning)

- ^ a b c Popular Front of Latvia (11 December 1990). "The Popular Front of Latvia announcement to all supporters of independence". Archived from the original on 2022-03-31. Retrieved 2007-08-17.

- ^ a b c d e f "The History of confrontation". Archived from the original on 2007-07-10. Retrieved 2007-08-17.

- ^ "Session of Supreme Council on 2 January 1991" (in Latvian). 2 January 1991. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 2007-08-17.

- ^ Einars Cilinskis (9 January 1991). "Session of Supreme council on 9 January 1991" (in Latvian). Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 2007-08-13.

Jo mēs zinām, ka Preses namā tagad drukā tikai komunistu presi. (English: Because we know that in Preses Nams now only communist press is printed)

- ^ a b c d e "Atmiņas par barikāžu dienām" (in Latvian). 2001. Archived from the original (doc) on 2007-09-28. Retrieved 2007-08-13.

- ^ Aleksandrs Kiršteins (13 January 1991). "Morning session of Supreme Council on 13 January 1991" (in Latvian). Archived from the original on 4 May 2019. Retrieved 2007-08-13.

Protams, ka uzbrukums Lietuvai mums ir jāsaprot kā uzbrukums Latvijai un Igaunijai. (English: Of course, we should perceive the attack on Lithuania as an attack on Latvia and Estonia)

- ^ "Evening session of Supreme council on 13 January 1991" (in Latvian). 13 January 1991. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 2007-08-17.

- ^ a b "Visi uz barikādēm!" (in Latvian). 14 January 2005. Retrieved 2007-08-17.

- ^ a b c d "Adoption of the Declaration of Independence, the Barricades (1990–1991)". Ministry of Defence of Latvia. Retrieved February 6, 2018.

- ^ Mirlins 2016, p. 107

- ^ Mirlins 2016, p. 259

- ^ a b Mirlins 2016, p. 181

- ^ Zigurds Vidiņš (1999). Kurš pavēlēja šāvējiem? [Who ordered the shooters?] (wmv) (Documentary). Event occurs at 2:12. Retrieved 2007-08-17.[dead link]

- ^ Supreme Council of the Republic of Latvia (10 September 1991). "Latvijas Republikas Augstākās Padomes lēmums "Par dažu sabiedrisko un sabiedriski politisko organizāciju darbības izbeigšanu"" (in Latvian). Latvijas Vēstnesis. Retrieved 2007-08-17.

- ^ "Latvijas Republikas Augstākās tiesas dokumenti Par A.Rubika un O.Potreki krimināllietu" (in Latvian). Latvijas Vēstnesis. Retrieved 2007-08-17.

- ^ 1999 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices - Latvia US Department of State. 23 February 2000. Retrieved 2013-06-13.

- ^ "The End of the Russian Fairy Tale" Anne Applebaum; Slate, July 18, 2014

- ^ "Barricades of January 1991 and their role in restoring Latvia's independence" (PDF). State Chancellery of Latvia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 August 2020. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- ^ "Barikāžu dalībnieku atbalsta fonds". Latvijas Enciklopēdija. Vol. I Volume. Riga: SIA "Valērija Belokoņa izdevniecība". 2002. p. 531. ISBN 9984-9482-1-8.

- ^ "1991. gada barikāžu muzejs". Retrieved 2007-08-13.

- ^ "Barikāžu dalībnieku atceres diena". Latvijas Enciklopēdija. Vol. I Volume. Riga: SIA "Valērija Belokoņa izdevniecība". 2002. p. 531. ISBN 9984-9482-1-8.

- ^ "Barikāžu dalībnieka piemiņas zīme". Latvijas Enciklopēdija. Vol. I Volume. Riga: SIA "Valērija Belokoņa izdevniecība". 2002. p. 531. ISBN 9984-9482-1-8.

Bibliography

[edit]- Mirlins, Aleksandrs, ed. (2016). Janvāra hronika: Barikāžu laika preses relīzes/January Chronicles: Press Releases from the Barricades (PDF). Translated by Puzo, Ivo; Upmace, Ieva. Riga: Saeima. ISBN 978-9934-14-777-7.

External links

[edit]- Video: 'The Keys' traces the time of the barricades. 27 January 2020. Public Broadcasting of Latvia. Retrieved: 30 January 2020.

- See: 25 historic photos from Riga during the Barricades. January 19, 2018. Public Broadcasting of Latvia. Retrieved: 6 February 2018.

- Five stories from the 1991 Rīga barricades. 27 January 2020. Public Broadcasting of Latvia. Retrieved: 20 January 2020.