Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

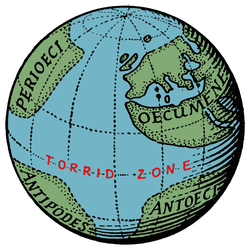

Torrid zone

View on Wikipedia

The torrid zone was the name given by ancient Greek and Roman geographers to the equatorial area of the Earth, so hot that it was thought to be impenetrable to sailors or explorers. That notion became a deterrent for European explorers until the 15th century.

Origin

[edit]Aristotle, like all classical thinkers, knew that the world was a sphere. He posited that the western half of the temperate zone on the other side of the globe from Greece might be habitable and that, because of symmetry, there must be in the Southern Hemisphere a temperate zone corresponding to that in the northern. He thought, however, that the excessive heat in the torrid zone would prevent the exploration.[1]

Strabo referred to:

the meridian through Syene is drawn approximately along the course of the Nile from Meroë to Alexandria, and this distance is about ten thousand stadia [~1,800 km]; and Syene must lie in the centre of that distance; so that the distance from Syene to Meroë is five thousand stadia [~900 km]. And when you have proceeded about three thousand stadia [~550 km] in a straight line south of Meroë, the country is no longer inhabitable on account of the heat, and therefore the parallel though these regions, being the same as that through the Cinnamon-producing Country, must be put down as the limit and the beginning of our inhabited world on the South.[2]

In 8 AD the poet Ovid wrote in his Metamorphoses.

...the celestial vault is cut by two zones on the right and two on the left, and there is a fifth zone between, hotter than these [i.e., the Milky Way], so did the providence of God mark off the enclosed mass with the same number of zones, and the same tracts were stamped upon the earth. The central zone of these may not be dwelt in by reason of the heat[3]

Pomponius Mela, the first Roman geographer, asserted that the Earth had two habitable zones, a north and a south one. The second population were known as Antichthones. However, it would be impossible to get into contact with each other because of the unbearable heat at the equator (De situ orbis 1.4). The term torrid is from Latin torridus, "burned, parched."[4]

Proved wrong

[edit]Many Europeans had assumed that Cape Bojador, in Western Sahara, marked the beginning of the impenetrable torrid zone until 1434, when the Portuguese sailed past the cape and reported that no torrid zone existed.[5]

References

[edit]- ^ Sanderson, Marie (April 1999). "The Classification of Climates from Pythagoras to Koeppen". Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. 80 (4): 669–673. Bibcode:1999BAMS...80..669S. doi:10.1175/1520-0477(1999)080<0669:TCOCFP>2.0.CO;2. JSTOR 26214921.

- ^ Strabo. GEOGRAPHY. Book II Chapter 5. Retrieved 31 August 2023.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Ovid. Metamorphoses, Book I.

- ^ "A Grammatical Dictionary of Botanical Latin". www.mobot.org.

- ^ Hansen, Valerie; Curtis, Kenneth R. (2015). Voyages in World History, Brief. Cengage Learning. p. 335. ISBN 9781305537705. Retrieved 28 March 2023.