Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Treemapping

View on Wikipedia

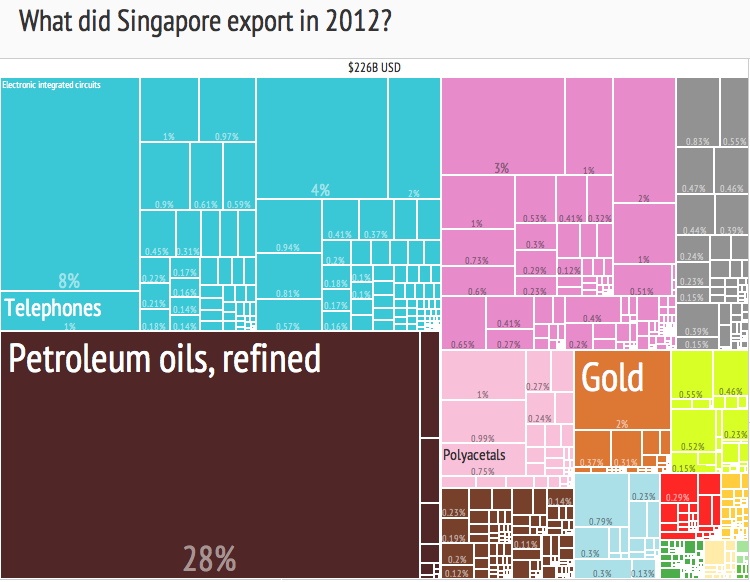

In information visualization and computing, treemapping is a method for displaying hierarchical data using nested figures, usually rectangles.

Treemaps display hierarchical (tree-structured) data as a set of nested rectangles. Each branch of the tree is given a rectangle, which is then tiled with smaller rectangles representing sub-branches. A leaf node's rectangle has an area proportional to a specified dimension of the data.[1] Often the leaf nodes are colored to show a separate dimension of the data.

When the color and size dimensions are correlated in some way with the tree structure, one can often easily see patterns that would be difficult to spot in other ways, such as whether a certain color is particularly prevalent. A second advantage of treemaps is that, by construction, they make efficient use of space. As a result, they can legibly display thousands of items on the screen simultaneously.

Tiling algorithms

[edit]To create a treemap, one must define a tiling algorithm, that is, a way to divide a region into sub-regions of specified areas. Ideally, a treemap algorithm would create regions that satisfy the following criteria:

- A small aspect ratio—ideally close to one. Regions with a small aspect ratio (i.e., fat objects) are easier to perceive.[2]

- Preserve some sense of the ordering in the input data (ordered).

- Change to reflect changes in the underlying data (high stability).

These properties have an inverse relationship. As the aspect ratio is optimized, the order of placement becomes less predictable. As the order becomes more stable, the aspect ratio is degraded.[example needed]

Rectangular treemaps

[edit]To date, fifteen primary rectangular treemap algorithms have been developed:

| Algorithm | Order | Aspect ratios | Stability |

|---|---|---|---|

| BinaryTree | partially ordered | high | stable |

| Slice And Dice[4] | ordered | very high | stable |

| Strip[5] | ordered | medium | medium stability |

| Pivot by middle[6] | ordered | medium | medium stability |

| Pivot by split[6] | ordered | medium | low stability |

| Pivot by size[6] | ordered | medium | medium stability |

| Split[7] | ordered | medium | medium stability |

| Spiral[8] | ordered | medium | medium stability |

| Hilbert[9] | ordered | medium | medium stability |

| Moore[9] | ordered | medium | medium stability |

| Squarified[10] | ordered | low | low stability |

| Mixed Treemaps[11] | unordered | low | medium stability |

| Approximation[12] | unordered | low | medium stability |

| Git[13] | unordered | medium | stable |

| Local moves[14] | unordered | medium | stable |

Convex treemaps

[edit]Rectangular treemaps have the disadvantage that their aspect ratio might be arbitrarily high in the worst case. As a simple example, if the tree root has only two children, one with weight and one with weight , then the aspect ratio of the smaller child will be , which can be arbitrarily high. To cope with this problem, several algorithms have been proposed that use regions that are general convex polygons, not necessarily rectangular.

Convex treemaps were developed in several steps, each step improved the upper bound on the aspect ratio. The bounds are given as a function of - the total number of nodes in the tree, and - the total depth of the tree.

- Onak and Sidiropoulos[15] proved an upper bound of .

- De-Berg and Onak and Sidiropoulos[16] improve the upper bound to , and prove a lower bound of .

- De-Berg and Speckmann and van-der-Weele[17] improve the upper bound to , matching the theoretical lower bound. (For the special case where the depth is 1, they present an algorithm that uses only four classes of 45-degree-polygons (rectangles, right-angled triangles, right-angled trapezoids and 45-degree pentagons), and guarantees an aspect ratio of at most 34/7.)

The latter two algorithms operate in two steps (greatly simplified for clarity):

- The original tree is converted to a binary tree: each node with more than two children is replaced by a sub-tree in which each node has exactly two children.

- Each region representing a node (starting from the root) is divided to two, using a line that keeps the angles between edges as large as possible. It is possible to prove that, if all edges of a convex polygon are separated by an angle of at least , then its aspect ratio is . It is possible to ensure that, in a tree of depth , the angle is divided by a factor of at most , hence the aspect ratio guarantee.

Orthoconvex treemaps

[edit]In convex treemaps, the aspect ratio cannot be constant - it grows with the depth of the tree. To attain a constant aspect-ratio, Orthoconvex treemaps[17] can be used. There, all regions are orthoconvex rectilinear polygons with aspect ratio at most 64; and the leaves are either rectangles with aspect ratio at most 8, or L-shapes or S-shapes with aspect ratio at most 32.

For the special case where the depth is 1, they present an algorithm that uses only rectangles and L-shapes, and the aspect ratio is at most ; the internal nodes use only rectangles with aspect ratio at most .

Other treemaps

[edit]- Voronoi Treemaps

- [18] based on Voronoi diagram calculations. The algorithm is iterative and does not give any upper bound on the aspect ratio.

- Jigsaw Treemaps[19]

- based on the geometry of space-filling curves. They assume that the weights are integers and that their sum is a square number. The regions of the map are rectilinear polygons and highly non-ortho-convex. Their aspect ratio is guaranteed to be at most 4.

- GosperMaps

- [20] based on the geometry of Gosper curves. It is ordered and stable, but has a very high aspect ratio.

History

[edit]

Area-based visualizations have existed for decades. For example, mosaic plots (also known as Marimekko diagrams) use rectangular tilings to show joint distributions (i.e., most commonly they are essentially stacked column plots where the columns are of different widths). The main distinguishing feature of a treemap, however, is the recursive construction that allows it to be extended to hierarchical data with any number of levels. This idea was invented by professor Ben Shneiderman at the University of Maryland Human – Computer Interaction Lab in the early 1990s. [21][22] Shneiderman and his collaborators then deepened the idea by introducing a variety of interactive techniques for filtering and adjusting treemaps.

These early treemaps all used the simple "slice-and-dice" tiling algorithm. Despite many desirable properties (it is stable, preserves ordering, and is easy to implement), the slice-and-dice method often produces tilings with many long, skinny rectangles. In 1994 Mountaz Hascoet and Michel Beaudouin-Lafon invented a "squarifying" algorithm, later popularized by Jarke van Wijk, that created tilings whose rectangles were closer to square. In 1999 Martin Wattenberg used a variation of the "squarifying" algorithm that he called "pivot and slice" to create the first Web-based treemap, the SmartMoney Map of the Market, which displayed data on hundreds of companies in the U.S. stock market. Following its launch, treemaps enjoyed a surge of interest, particularly in financial contexts.[citation needed]

A third wave of treemap innovation came around 2004, after Marcos Weskamp created the Newsmap, a treemap that displayed news headlines. This example of a non-analytical treemap inspired many imitators, and introduced treemaps to a new, broad audience.[citation needed] In recent years, treemaps have made their way into the mainstream media, including usage by the New York Times.[23][24] The Treemap Art Project[25] produced 12 framed images for the National Academies (United States), shown at the Every AlgoRiThm has ART in It exhibit[26] in Washington, DC and another set for the collection of Museum of Modern Art in New York.

See also

[edit]- Disk space analyzer

- Data and information visualization

- Marimekko Chart, a similar concept with one level of explicit hierarchy.

References

[edit]- ^ Li, Rita Yi Man; Chau, Kwong Wing; Zeng, Frankie Fanjie (2019). "Ranking of Risks for Existing and New Building Works". Sustainability. 11 (10): 2863. Bibcode:2019Sust...11.2863L. doi:10.3390/su11102863.

- ^ Kong, N; Heer, J; Agrawala, M (2010). "Perceptual Guidelines for Creating Rectangular Treemaps". IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics. 16 (6): 990–8. Bibcode:2010ITVCG..16..990K. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.688.4140. doi:10.1109/TVCG.2010.186. PMID 20975136. S2CID 11597084.

- ^ Vernier, E.; Sondag, M.; Comba, J.; Speckmann, B.; Telea, A.; Verbeek, K. (2020). "Quantitative Comparison of Time-Dependent Treemaps". Computer Graphics Forum. 39 (3): 393–404. arXiv:1906.06014. doi:10.1111/cgf.13989. S2CID 189898065.

- ^ Shneiderman, Ben (2001). "Ordered treemap layouts" (PDF). Infovis: 73.

- ^ Benjamin, Bederson; Shneiderman, Ben; Wattenberg, Martin (2002). "Ordered and quantum treemaps: Making effective use of 2D space to display hierarchies" (PDF). ACM Transactions on Graphics. 21 (4): 833–854. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.145.2634. doi:10.1145/571647.571649. hdl:1903/6486. S2CID 7253456.

- ^ a b c Shneiderman, Ben; Wattenberg, Martin (2001). "Ordered treemap layouts". IEEE Symposium on Information Visualization: 73–78.

- ^ Engdahl, Björn. Ordered and quantum treemaps: Making effective use of 2D space to display hierarchies.

- ^ Tu, Y.; Shen, H. (2007). "Visualizing changes of hierarchical data using treemaps" (PDF). IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics. 13 (6): 1286–1293. Bibcode:2007ITVCG..13.1286T. doi:10.1109/TVCG.2007.70529. PMID 17968076. S2CID 14206074. Archived (PDF) from the original on Aug 8, 2022.

- ^ a b Tak, S.; Cockburn, A. (2013). "Enhanced spatial stability with Hilbert and Moore treemaps" (PDF). IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics. 19 (1): 141–148. Bibcode:2013ITVCG..19..141T. doi:10.1109/TVCG.2012.108. PMID 22508907. S2CID 6099935.

- ^ Bruls, Mark; Huizing, Kees; van Wijk, Jarke J. (2000). "Squarified treemaps". In de Leeuw, W.; van Liere, R. (eds.). Data Visualization 2000: Proc. Joint Eurographics and IEEE TCVG Symp. on Visualization (PDF). Springer-Verlag. pp. 33–42..

- ^ Roel Vliegen; Erik-Jan van der Linden; Jarke J. van Wijk. "Visualizing Business Data with Generalized Treemaps" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 24, 2011. Retrieved February 24, 2010.

- ^ Nagamochi, H.; Abe, Y.; Wattenberg, Martin (2007). "An approximation algorithm for dissect-ing a rectangle into rectangles with specified areas". Discrete Applied Mathematics. 155 (4): 523–537. doi:10.1016/j.dam.2006.08.005.

- ^ Faccin Vernier, Eduardo; Dihl Comba, Joao Luiz; Telea, Alexandru C. (2018). "Quantitative Comparison of Dynamic Treemaps for Software Evolution Visualization" (PDF). Proceedings of the Sixth IEEE Working Conference on Software Visualization. VISSOFT 2018. pp. 99–106. doi:10.1109/VISSOFT.2018.00018. hdl:11370/f2713bfd-5be7-4db4-89f8-cd161b033ce9. S2CID 53278664. Retrieved 2025-01-15.

- ^ Sondag, M.; Speckmann, B.; Verbeek, K. (2018). "Stable treemaps via local moves" (PDF). IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics. 24 (1): 729–738. Bibcode:2018ITVCG..24..729S. doi:10.1109/TVCG.2017.2745140. PMID 28866573. S2CID 27739774.

- ^ Krzysztof Onak; Anastasios Sidiropoulos. "Circular Partitions with Applications to Visualization and Embeddings". Retrieved June 26, 2011.

- ^ Mark de Berg; Onak, Krzysztof; Sidiropoulos, Anastasios (2013). "Fat Polygonal Partitions with Applications to Visualization and Embeddings". Journal of Computational Geometry. 4 (1): 212–239. arXiv:1009.1866.

- ^ a b De Berg, Mark; Speckmann, Bettina; Van Der Weele, Vincent (2014). "Treemaps with bounded aspect ratio". Computational Geometry. 47 (6): 683. arXiv:1012.1749. doi:10.1016/j.comgeo.2013.12.008. S2CID 12973376.. Conference version: Convex Treemaps with Bounded Aspect Ratio (PDF). EuroCG. 2011.

- ^ Balzer, Michael; Deussen, Oliver (2005). "Voronoi Treemaps". In Stasko, John T.; Ward, Matthew O. (eds.). IEEE Symposium on Information Visualization (InfoVis 2005), 23-25 October 2005, Minneapolis, MN, USA (PDF). IEEE Computer Society. p. 7..

- ^ Wattenberg, Martin (2005). "A Note on Space-Filling Visualizations and Space-Filling Curves". In Stasko, John T.; Ward, Matthew O. (eds.). IEEE Symposium on Information Visualization (InfoVis 2005), 23-25 October 2005, Minneapolis, MN, USA (PDF). IEEE Computer Society. p. 24..

- ^ Auber, David; Huet, Charles; Lambert, Antoine; Renoust, Benjamin; Sallaberry, Arnaud; Saulnier, Agnes (2013). "Gosper Map: Using a Gosper Curve for laying out hierarchical data". IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics. 19 (11): 1820–1832. Bibcode:2013ITVCG..19.1820A. doi:10.1109/TVCG.2013.91. PMID 24029903. S2CID 15050386..

- ^ Shneiderman, Ben (1992). "Tree visualization with tree-maps: 2-d space-filling approach". ACM Transactions on Graphics. 11: 92–99. doi:10.1145/102377.115768. hdl:1903/367. S2CID 1369287.

- ^ Ben Shneiderman; Catherine Plaisant (June 25, 2009). "Treemaps for space-constrained visualization of hierarchies ~ Including the History of Treemap Research at the University of Maryland". Retrieved February 23, 2010.

- ^ Cox, Amanda; Fairfield, Hannah (February 25, 2007). "The health of the car, van, SUV, and truck market". The New York Times. Retrieved March 12, 2010.

- ^ Carter, Shan; Cox, Amanda (February 14, 2011). "Obama's 2012 Budget Proposal: How $3.7 Trillion is Spent". The New York Times. Retrieved February 15, 2011.

- ^ "Treemap Art". Archived from the original on Dec 5, 2023.

- ^ "Every AlgoRiThm has ART in it: Treemap Art Project". CPNAS. Archived from the original on Oct 8, 2023.

External links

[edit]- Treemap Art Project produced exhibit for the National Academies in Washington, DC

- "Discovering Business Intelligence Using Treemap Visualizations", Ben Shneiderman, April 11, 2006

- Comprehensive survey and bibliography of Tree Visualization techniques

- Vliegen, Roel; van Wijk, Jarke J.; van der Linden, Erik-Jan (September–October 2006). "Visualizing Business Data with Generalized Treemaps" (PDF). IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics. 12 (5): 789–796. Bibcode:2006ITVCG..12..789V. doi:10.1109/TVCG.2006.200. PMID 17080801. S2CID 18891326. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 July 2011.

- History of Treemaps by Ben Shneiderman.

- Hypermedia exploration with interactive dynamic maps Paper by Zizi and Beaudouin-Lafon introducing the squarified treemap layout algorithm (named "improved treemap layout" at the time).

- Indiana University description

- Live interactive treemap based on crowd-sourced discounted deals from Flytail Group

- Treemap sample in English from The Hive Group

- Several treemap examples made with Macrofocus TreeMap

- Visualizations using dynamic treemaps and online treemapping software by drasticdata

Treemapping

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Principles

Treemapping is a visualization technique that displays hierarchical, tree-structured data using nested rectangles or other shapes, where the area of each shape is proportional to a quantitative value associated with the corresponding node, such as file size or sales volume.[1] This method maps the entire hierarchy onto a two-dimensional display area, ensuring full utilization of the available space through recursive partitioning based on the tree's structure.[2] The primary purpose of treemapping is to represent large hierarchies compactly within limited screen space, enabling users to compare relative sizes, detect patterns, and navigate nested structures more effectively than with traditional node-link diagrams or textual listings.[1] Developed in the early 1990s to overcome challenges in visualizing complex file systems and disk usage, it allows for the simultaneous display of thousands of nodes while preserving both structural relationships and quantitative attributes.[2] At its core, treemapping employs a space-filling approach that recursively subdivides the display region according to the branching of the hierarchy, with each level's partitions reflecting the proportional weights of child nodes.[1] It supports visualization of multiple data dimensions by encoding size through area and additional attributes—such as categories or secondary values—through color, shading, or texture, facilitating rapid identification of outliers or trends.[2] For instance, in a treemap of a computer's file system, directories appear as larger enclosing rectangles containing smaller sub-rectangles for files, with areas scaled to storage consumption and colors indicating file types.[1]Visual Encoding and Design Goals

In treemaps, visual encoding maps hierarchical data attributes to spatial and aesthetic properties to facilitate comprehension of structure and quantitative values. The primary encoding uses rectangle area to represent a quantitative measure, such as node size or value, ensuring proportionality for accurate size comparisons across elements.[2] Nesting of rectangles encodes the hierarchy, with child nodes fully contained within parent rectangles to depict levels of containment, typically progressing from outer to inner rectangles for deeper levels.[2] Additional qualitative attributes, like categories or types (e.g., file extensions), are encoded via color, shading, or texture to differentiate groups without altering spatial proportions.[2] Optional elements such as borders, labels, or icons provide identification and context, though their use is balanced to avoid visual clutter in dense layouts.[5] Design goals for treemaps prioritize readability, comparability, and perceptual efficiency. A key objective is minimizing aspect ratios to avoid elongated rectangles, which hinder size estimation and visual scanning; the aspect ratio of a rectangle is defined as , where is width and is height, with ideal values approaching 1 for near-square shapes that support better labeling and selection.[5] Preservation of reading order maintains a consistent left-to-right and top-to-bottom traversal, aligning with natural scanning patterns to aid item location and pattern recognition.[5] Stability ensures minimal layout disruption during data updates, reducing cognitive load by keeping familiar elements in predictable positions and minimizing animation flicker.[5] The enclosure principle reinforces hierarchical clarity by guaranteeing that all child rectangles are wholly contained within their parent, preventing ambiguous relationships.[2] Usability in treemaps is enhanced through interactive features that address scalability for large datasets. Support for zooming allows users to magnify regions for detailed inspection while preserving an overview context, filtering enables selective display of subsets based on criteria like value thresholds, and details-on-demand provides supplementary information (e.g., tooltips) upon interaction, aligning with established visualization tasks.[6] These mechanisms collectively promote exploratory analysis without overwhelming the display.[6]Tiling Algorithms

Rectangular Treemaps

Rectangular treemaps represent the most common form of treemapping, employing recursive subdivision of an enclosing rectangle into smaller, axis-aligned rectangles whose areas are proportional to the sizes of the corresponding nodes in a hierarchical dataset.[2] This approach ensures a space-filling layout that preserves the tree structure through nesting, with each rectangle's dimensions encoding both node size and hierarchy depth.[7] The foundational algorithm for rectangular treemaps is the slice-and-dice method, introduced by Shneiderman in 1992. It operates by alternately partitioning the current rectangle horizontally and vertically based on tree levels: even levels use vertical splits, odd levels horizontal ones. Specifically, for a given rectangle and node, the algorithm draws split lines proportional to child node sizes (e.g., the first vertical split at position x_3 = x_1 + \frac{\text{Size}(\text{child}{{grok:render&&&type=render_inline_citation&&&citation_id=1&&&citation_type=wikipedia}})}{\text{Size}(\text{root})} \times (x_2 - x_1)), then recurses on subrectangles. This yields linear time complexity of , where is the number of nodes, making it efficient for large hierarchies. However, it often produces rectangles with high aspect ratios—such as narrow strips—due to unbalanced splits, which can hinder visual comparison of sizes.[2][5] To address the aspect ratio issues, Bruls et al. proposed the squarified algorithm in 2000, which prioritizes near-square shapes by sorting leaf nodes in decreasing order of size and greedily adding them to rows or columns. The core procedure,squarify(children, row, w), evaluates whether adding the next child improves the worst aspect ratio in the current row: if , it adds and recurses; otherwise, it lays out the current row, starts a new one in the remaining space, and recurses on the rest. Here, , with as individual areas and as their sum. This results in significantly better aspect ratios (e.g., average 3.21 on stock datasets) compared to slice-and-dice (369.83), though it requires time due to sorting and can disrupt node ordering.[7][5]

Shneiderman and Wattenberg extended this in 2001 with the ordered treemap algorithm, specifically the pivot-by-split-size variant, to balance shape quality with order preservation. It selects the largest child as a pivot and splits the remaining siblings into three ordered groups (before and after the pivot) to minimize the pivot rectangle's aspect ratio, choosing the split dimension (horizontal if width ≥ height, else vertical) where the maximum child-to-total size ratio is minimized. The split point is computed by distributing items to achieve near-square pivot proportions, recursing on the subregions. This improves stability over squarified layouts (e.g., layout distance change of 2.93–7.29 vs. 10.10 on test data) while maintaining moderate aspect ratios (e.g., 17.65–33.01 on stocks), at an average time complexity akin to quicksort.[8][5]

Comparisons across these algorithms highlight key trade-offs: slice-and-dice excels in speed (e.g., 20,000 nodes in 0.03 seconds) and stability but yields poor aspect ratios; squarified optimizes shapes for readability at the cost of instability and reordered nodes; ordered variants like pivot-by-split-size offer a compromise, with better preservation of input order and moderate performance, though slower than slice-and-dice in worst cases (). Quantitative evaluations on datasets like 535-stock hierarchies show ordered methods achieving readability scores (0.61) competitive with squarified while outperforming slice-and-dice in shape quality.[5]