Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

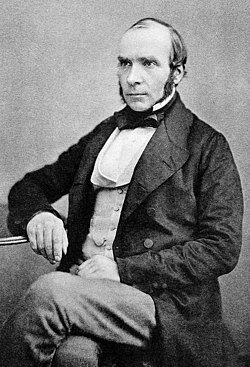

John Snow

View on Wikipedia

John Snow (15 March 1813 – 16 June 1858[1]) was an English physician and a leader in the development of anaesthesia and medical hygiene. He is considered one of the founders of modern epidemiology and early germ theory, in part because of his work in tracing the source of a cholera outbreak in London's Soho, which he identified as a particular public water pump. Snow's findings inspired fundamental changes in the water and waste systems of London, which led to similar changes in other cities, and a significant improvement in general public health around the world.[2]

Key Information

Early life and education

[edit]Snow was born on 15 March 1813 in York, England, the first of nine children born to William and Frances Snow in their North Street home, and was baptised at All Saints' Church, North Street, York. His father was a labourer[3] who worked at a local coal yard, by the Ouse, constantly replenished from the Yorkshire coalfield by barges, but later was a farmer in a small village to the north of York.[4]

The neighbourhood was one of the poorest in the city, and was frequently in danger of flooding because of its proximity to the River Ouse. Growing up, Snow experienced unsanitary conditions and contamination in his hometown. Most of the streets were unsanitary and the river was contaminated by runoff water from market squares, cemeteries and sewage.[5]

From a young age, Snow demonstrated an aptitude for mathematics. In 1827, when he was 14, he obtained a medical apprenticeship with William Hardcastle in the area of Newcastle-upon-Tyne. In 1832, during his time as a surgeon-apothecary apprentice, he encountered a cholera epidemic for the first time in Killingworth, a coal-mining village.[6] Snow treated many victims of the disease and thus gained experience. Eventually he adjusted to teetotalism and led a life characterized by abstinence, signing an abstinence pledge in 1835. Snow was also a vegetarian and tried to only drink distilled water that was "pure".[5] Between 1832 and 1835 Snow worked as an assistant to a colliery surgeon, first in Burnopfield, County Durham, and then in Pateley Bridge, West Riding of Yorkshire. In October 1836 he enrolled at the Hunterian school of medicine on Great Windmill Street, London.[7]

Career

[edit]In the 1830s, Snow's colleague at the Newcastle Infirmary was surgeon Thomas Michael Greenhow. The surgeons worked together conducting research on England's cholera epidemics, both continuing to do so for many years.[8][9][10][11]

In 1837, Snow began working at the Westminster Hospital. Admitted as a member of the Royal College of Surgeons of England on 2 May 1838, he graduated from the University of London in December 1844 and was admitted to the Royal College of Physicians in 1850. Snow was a founding member of the Epidemiological Society of London which was formed in May 1850 in response to the cholera outbreak of 1849. By 1856, Snow and Greenhow's nephew, Dr. E.H. Greenhow were some of a handful of esteemed medical men of the society who held discussions on this "dreadful scourge, the cholera".[12][13][14]

After finishing his medical studies in the University of London, he earned his MD in 1844. Snow set up his practice at 54 Frith Street in Soho as a surgeon and general practitioner. John Snow contributed to a wide range of medical concerns including anaesthesiology. He was a member of the Westminster Medical Society, an organisation dedicated to clinical and scientific demonstrations. Snow gained prestige and recognition all the while being able to experiment and pursue many of his scientific ideas. He was a speaker multiple times at the society's meetings and he also wrote and published articles. He was especially interested in patients with respiratory diseases and tested his hypothesis through animal studies. In 1841, he wrote, On Asphyxiation, and on the Resuscitation of Still-Born Children, which is an article that discusses his discoveries on the physiology of neonatal respiration, oxygen consumption and the effects of body temperature change.[15]

In 1857, Snow made an early and often overlooked[16] contribution to epidemiology in a pamphlet, On the adulteration of bread as a cause of rickets.[17]

Anaesthesia

[edit]

Snow's interest in anaesthesia and breathing was evident from 1841 and beginning in 1843, he experimented with ether to see its effects on respiration.[5] Only a year after ether was introduced to Britain, in 1847, he published a short work titled, On the Inhalation of the Vapor of Ether, which served as a guide for its use. At the same time, he worked on various papers that reported his clinical experience with anaesthesia, noting reactions, procedures and experiments. Within two years of ether being introduced, Snow was the most accomplished anaesthetist in Britain. London's principal surgeons suddenly wanted his assistance.[5]

As well as ether, John Snow studied chloroform, which was introduced in 1847 by James Young Simpson, a Scottish obstetrician. He realised that chloroform was much more potent and required more attention and precision when administering it. Snow first realised this with Hannah Greener, a 15-year-old patient who died on 28 January 1848 after a surgical procedure that required the cutting of her toenail. She was administered chloroform by covering her face with a cloth dipped in the substance. However, she quickly lost pulse and died. After investigating her death and a couple of deaths that followed, he realized that chloroform had to be administered carefully and published his findings in a letter to The Lancet.[5]

John Snow was one of the first physicians to study and calculate dosages for the use of ether and chloroform as surgical anaesthetics, allowing patients to undergo surgical and obstetric procedures without the distress and pain they would otherwise experience. He designed the apparatus to safely administer ether to the patients and also designed a mask to administer chloroform.[18] Snow published an article on ether in 1847 entitled On the Inhalation of the Vapor of Ether.[19] A longer version entitled On Chloroform and Other Anaesthetics and Their Action and Administration was published posthumously in 1858.[20]

Although he thoroughly worked with ether as an anaesthetic, he never attempted to patent it; instead, he continued to work and publish written works on his observations and research.

Obstetric anaesthesia

[edit]Snow's work and findings were related to both anaesthesia and the practice of childbirth. His experience with obstetric patients was extensive and used different substances including ether, amylene and chloroform to treat his patients. However, chloroform was the easiest drug to administer. He treated 77 obstetric patients with chloroform. He would apply the chloroform at the second stage of labour and controlled the amount without completely putting the patients to sleep. Once the patient was delivering the baby, they would only feel the first half of the contraction and be on the border of unconsciousness, but not fully there. Regarding administration of the anaesthetic, Snow believed that it would be safer if another person that was not the surgeon applied it.[15]

The use of chloroform as an anaesthetic for childbirth was seen as unethical by many physicians and even the Church of England. However, on 7 April 1853, Queen Victoria asked John Snow to administer chloroform during the delivery of her eighth child, Leopold. He then repeated the procedure for the delivery of her daughter Beatrice in 1857.[21] This led to wider acceptance of obstetrical anaesthesia.[5]

Cholera

[edit]

Snow was a skeptic of the then-dominant miasma theory that stated that diseases such as cholera and bubonic plague were caused by pollution or a noxious form of "bad air". The germ theory of disease had not yet been developed, so Snow did not understand the mechanism by which the disease was transmitted. His observation of the evidence led him to discount the theory of foul air. He first published his theory in an 1849 essay, On the Mode of Communication of Cholera,[22] followed by a more detailed treatise in 1855 incorporating the results of his investigation of the role of the water supply in the Soho epidemic of 1854.[23][24]

By talking to local residents (with the help of Henry Whitehead), he identified the source of the outbreak as the public water pump on Broad Street (now Broadwick Street). Although Snow's chemical and microscope examination of a water sample from the Broad Street pump did not conclusively prove its danger, his studies of the pattern of the disease were convincing enough to persuade the local council to disable the well pump by removing its handle (force rod). This action has been commonly credited as ending the outbreak, but Snow observed that the epidemic may have already been in rapid decline:

There is no doubt that the mortality was much diminished, as I said before, by the flight of the population, which commenced soon after the outbreak; but the attacks had so far diminished before the use of the water was stopped, that it is impossible to decide whether the well still contained the cholera poison in an active state, or whether, from some cause, the water had become free from it.[23]: 51–52

Snow later used a dot map to illustrate the cluster of cholera cases around the pump. He also used statistics to illustrate the connection between the quality of the water source and cholera cases. He showed that homes supplied by the Southwark and Vauxhall Waterworks Company, which was taking water from sewage-polluted sections of the Thames, had a cholera rate fourteen times that of those supplied by Lambeth Waterworks Company, which obtained water from the upriver, cleaner Seething Wells.[25][26] Snow's study was a major event in the history of public health and geography. It is regarded as the founding event of the science of epidemiology.[citation needed]

Snow wrote:

On proceeding to the spot, I found that nearly all the deaths had taken place within a short distance of the [Broad Street] pump. There were only ten deaths in houses situated decidedly nearer to another street-pump. In five of these cases the families of the deceased persons informed me that they always sent to the pump in Broad Street, as they preferred the water to that of the pumps which were nearer. In three other cases, the deceased were children who went to school near the pump in Broad Street...

With regard to the deaths occurring in the locality belonging to the pump, there were 61 instances in which I was informed that the deceased persons used to drink the pump water from Broad Street, either constantly or occasionally...

The result of the inquiry, then, is, that there has been no particular outbreak or prevalence of cholera in this part of London except among the persons who were in the habit of drinking the water of the above-mentioned pump well.

I had an interview with the Board of Guardians of St James's parish, on the evening of the 7th inst [7 September], and represented the above circumstances to them. In consequence of what I said, the handle of the pump was removed on the following day.

— John Snow, letter to the editor of the Medical Times and Gazette[27]

Researchers later discovered that this public well had been dug only 3 feet (0.9 m) from an old cesspit, which had begun to leak faecal bacteria. The cloth nappy of a baby, who had contracted cholera from another source, had been washed into this cesspit. Its opening was originally under a nearby house, which had been rebuilt farther away after a fire. The city had widened the street and the cesspit was lost. It was common at the time to have a cesspit under most homes. Most families tried to have their raw sewage collected and dumped in the Thames to prevent their cesspit from filling faster than the sewage could decompose into the soil.[28]

Thomas Shapter had conducted similar studies and used a point-based map for the study of cholera in Exeter, seven years before John Snow, although this did not identify the water supply problem that was later held responsible.[29]

Political controversy

[edit]After the cholera epidemic had subsided, government officials replaced the Broad Street pump handle. They had responded only to the urgent threat posed to the population, and afterward they rejected Snow's theory. To accept his proposal would have meant indirectly accepting the fecal-oral route of disease transmission, which was too unpleasant for most of the public to contemplate.[30]

It was not until 1866 that William Farr, one of Snow's chief opponents, realised the validity of his diagnosis when investigating another outbreak of cholera at Bromley by Bow and issued immediate orders that unboiled water was not to be drunk.[31]

Farr denied Snow's explanation of how exactly the contaminated water spread cholera, although he did accept that water had a role in the spread of the illness. In fact, some of the statistical data that Farr collected helped promote John Snow's views.[32]

Public health officials recognise the political struggles in which reformers have often become entangled.[33] During the annual Pumphandle Lecture in England, members of the John Snow Society remove and replace a pump handle to symbolise the continuing challenges for advances in public health.[34]

Personal life

[edit]Snow was known to swim as a hobby for exercise.[35] He became a vegetarian at the age of 17 and was a teetotaller.[35] He embraced a lacto-ovo vegetarian diet by supplementing his vegetables with dairy products and eggs for eight years. Whilst in his thirties he became a vegan.[35] His health deteriorated and he suffered a renal disorder which he attributed to his vegan diet so he took up meat-eating and drinking wine.[35] He continued drinking pure water (via boiling) throughout his adult life. He never married.[36]

In 1830, Snow became a member of the temperance movement. In 1845, he became a member of York Temperance Society.[35] After his health declined it was only about 1845 that he consumed a little wine to aid digestion.[35]

Snow lived at 18 Sackville Street, London, from 1852 to his death in 1858.[37]

Snow suffered a stroke while working in his London office on 10 June 1858. He was 45 years old at the time.[38] He never recovered, dying six days later on 16 June 1858. He was buried in Brompton Cemetery.[39]

It has been speculated that his premature death may have been related to his frequent exposure and experimentation with anesthetic gases, which is now known to have numerous adverse health effects. Snow administered and experimented with ether, chloroform, ethyl nitrate, carbon disulfide, benzene, bromoform, ethyl bromide and dichloroethane during his lifetime.[40]

Legacy and honours

[edit]

- A plaque commemorates Snow and his 1854 study in the place of the water pump on Broad Street (now Broadwick Street). It shows a water pump with its handle removed. The spot where the pump stood is covered with red granite.

- A public house nearby was named the "John Snow" in his honour.[41]

- The John Snow Society is named in his honour, and the society regularly meets at The John Snow pub. An annual Pumphandle Lecture is delivered each September by a leading authority in contemporary public health.

- His grave in Brompton Cemetery, London, is marked by a funerary monument.[42]

- In York a blue plaque on the west end of the Park Inn, a hotel in North Street, commemorates John Snow.

- Together with fellow pioneer of anaesthesia Joseph Thomas Clover, Snow is one of the heraldic supporters of the Royal College of Anaesthetists.[43]

- The Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland awards The John Snow Award, a bursary for undergraduate medical students undertaking research in the field of anaesthesia.

- Despite reports that Snow was awarded a prize by the Institut de France for his 1849 essay on cholera,[44] a 1950 letter from the Institut indicates that he received only a nomination for it.[45]

- In 1978 a public health research and consulting firm, John Snow, Inc, was founded.[citation needed]

- In 2001 the John Snow College was founded on the University of Durham's Queen's Campus in Stockton-on-Tees.[46]

- In 2003 John Snow was voted by readers in the United Kingdom of 'Hospital Doctor' magazine as 'the greatest doctor of all time'.[47]

- In 2009, the John Snow lecture theatre was opened by Anne, Princess Royal, at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine.[citation needed]

- In 2013 The Lancet printed a correction of its brief obituary of Snow, originally published in 1858: "The journal accepts that some readers may wrongly have inferred that The Lancet failed to recognise Dr Snow's remarkable achievements in the field of epidemiology and, in particular, his visionary work in deducing the mode of transmission of epidemic cholera."[48]

- In 2016, Katherine Tansley published a fictionalised account based on Snow's activities, in her historical novel The Doctor of Broad Street (Troubadour Books).

- In 2017 York Civic Trust erected a memorial to John Snow in the form of a pump with its handle removed, a blue plaque and an interpretation board, in North Street Gardens, York, close to his birthplace.[49]

See also

[edit]- William Budd, recognised that cholera was contagious

- The Ghost Map, book on cholera epidemiology

- Florence Nightingale, founder of modern nursing

- Filippo Pacini, isolated cholera

- Joseph Bazalgette, sewer engineer for London

References

[edit]- ^ "John Snow". Encyclopædia Britannica. 8 March 2018. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- ^ Vinten-Johansen et al. (2003)

- ^ Wedding Record of William Snow and Frances Empson, Huntington All Saints, 24 May 1812

- ^ Census 1841

- ^ a b c d e f Ramsay, Michael A. E. (6 January 2009). "John Snow, MD: anaesthetist to the Queen of England and pioneer epidemiologist". Proceedings (Baylor University. Medical Center). 19 (1): 24–28. doi:10.1080/08998280.2006.11928120. PMC 1325279. PMID 16424928.

- ^ Ball, Laura (2009). "Cholera and the Pump on Broad Street: The Life and Legacy of John Snow". The History Teacher. 43 (1): 105–119. JSTOR 40543358.

- ^ Thomas, KB. (1973) "John Snow" in Dictionary of Scientific Biography. Vol 12. New York, NY: Charles Scribner's Sons; pp. 502–503.

- ^ Tominey, Camilla (28 May 2020). "The Duchess of Cambridge's Ancestor Would Have Led The Fight Against Covid 19". Daily Telegraph. UK. PressReader. p. 25. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

Based in Tynemouth, near Newcastle, Dr Greenhow, his nephew Dr EH Greenhow and Dr John Snow were founding members of the Royal Society of Medicine's Epidemiological Society in the 1850s.... Dr Snow was Dr Greenhow's former surgery apprentice and Queen Victoria's personal anaesthetist...

- ^ Smith, D. (2017). Water-Supply and Public Health Engineering. Routledge. ISBN 9781351873550.

....Dr T.M. Greenhow, a Newcastle colleague of Dr John Snow, had published: Cholera: its non–contagious nature, and the best means of arresting its progress shortly ...

- ^ Greenhow, Thomas M. (1852). "Cholera from the east. A letter addressed to Mayor of Newcastle-upon-Tyne James Hodgson, Esq". E. Charnley.

- ^ Vinten-Johansen et al. (2003), pp. 30 & 198: "The senior surgeon was Thomas Michael Greenhow (1792–1881)" and "Consider also T. M. Greenhow: 'When patients rally from collapse, it is often most difficult to ascertain on what causes...'" respectively.

- ^ "London Epidemiology Society". UCLA. Retrieved 22 October 2012.

- ^ "The Lancet London: A Journal of British and Foreign Medicine ..., Volume 1... Epidemiological Society". Elsevier. 1856. p. 167.

The following members of the Epidemiological Society (10 gentleman) took part in the discussion....Drs. Snow, Greenhow...

- ^ Frerichs, R. "London Epidemiological Society". Department of Epidemiological (UCLA). Retrieved 18 March 2019.

...dreadful scourge, the cholera ....Snow as a founding member of .....(Tucker's) stimulating words led to a meeting on March 6, 1850 in Hanover Square, within walking distance of the Broad Street pump in the Soho region of London. It was here that the London Epidemiological Society was born.

- ^ a b Caton, Donald (January 2000). "John Snow's Practice of Obstetric Anesthesia". Anesthesiology: The Journal of the American Society of Anesthesiologists. 92 (1): 247–252. doi:10.1097/00000542-200001000-00037. PMID 10638922. S2CID 8117674.

- ^ Dunnigan, M. (2003). "Commentary: John Snow and alum-induced rickets from adulterated London bread: an overlooked contribution to metabolic bone disease". International Journal of Epidemiology. 32 (3): 340–1. doi:10.1093/ije/dyg160. PMID 12777415.

- ^ Snow, J. (1857). "On the Adulteration of Bread As a Cause of Rickets". The Lancet. 70 (1766): 4–5. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)21130-7.

Reedited in Snow, J. (2003). "On the adulteration of bread as a cause of rickets" (PDF). International Journal of Epidemiology. 32 (3): 336–7. doi:10.1093/ije/dyg153. PMID 12777413. - ^ John Snow (1813–58) Archived 6 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine. sciencemuseum.org.uk

- ^ Snow, John (1847) On the Inhalation of the Vapor of Ether. ph.ucla.edu

- ^ Snow, John (1858) On Chloroform and Other Anaesthetics and Their Action and Administration. London: John Churchill

- ^ "Anesthesia and Queen Victoria". John Snow. Department of Epidemiology UCLA School of Public Health. Retrieved 21 August 2007.

- ^ Snow, John (1849). On the Mode of Communication of Cholera (PDF). London: John Churchill. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 September 2015.

- ^ a b Snow, John (1855). On the Mode of Communication of Cholera (2nd ed.). London: John Churchill.

- ^ Gunn, S. William A.; Masellis, Michele (2007). Concepts and Practice of Humanitarian Medicine. Springer. pp. 87–. ISBN 978-0-387-72264-1.

- ^ "Location of water companies". www.ph.ucla.edu.

- ^ "Proof from Seething Wells". seethingwellswater.org.

- ^ Snow, John (1854). "The cholera near Golden-Square, and at Deptford". The Medical Times and Gazette. 2nd series. 9: 321–322.; see p. 322.

- ^ Klein, Gary (2014). Seeing What Others Don't. p. 73. ISBN 978-1480592803.

- ^ Shapter, Thomas (1849). The History of the Cholera in Exeter in 1832. London: John Churchill.

- ^ Chapelle, Frank (2005) Wellsprings. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press. p. 82. ISBN 0-8135-3614-6

- ^ Cadbury, Deborah (2003). Seven Wonders of the Industrial World. London and New York: Fourth Estate. pp. 189–192.

- ^ Eyler, John M. (April 1973). "William Farr on the Cholera: The Sanitarian's Disease Theory and the Statistician's Method". Journal of the History of Medicine. 28 (2): 79–100. doi:10.1093/jhmas/xxviii.2.79. PMID 4572629.

- ^ Donaldson, L.J. and Donaldson, R.J. (2005) Essential Public Health. Radcliffe Publishing. ISBN 1-900603-87-X. p. 105

- ^ "Pumphandle Lecture 2017". johnsnowsociety.org. The John Snow Society. 12 September 2017. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f Mather, J. D. (2004). 200 Years of British Hydrogeology. London: The Geological Society. p. 48. ISBN 1-86239-155-6

- ^ Snow, Stephanie J. (2004) "Snow, John (1813–1858)" in Oxford Dictionary of Biography.

- ^ JOHN SNOW'S HOMES. UCLA Department of Epidemiology, 2014. Retrieved 6 June 2014.

- ^ Johnson, Steven (2006). The Ghost Map. Riverhead Books. p. 206. ISBN 1-59448-925-4.

- ^ "List of notable occupants". Brompton Cemetery. Archived from the original (HTTP) on 23 August 2006. Retrieved 21 August 2007.

- ^ "John Snow's final rest - information on his death". www.ph.ucla.edu. Retrieved 7 January 2023.

- ^ Punt, Steve (12 May 2014). "Birmingham". The 3rd Degree. Season 3. Episode 6. Event occurs at 7:05. BBC Radio 4. Retrieved 1 December 2016.

- ^ "Brompton Cemetery Survey of London: Volume 41, Brompton". British History Online. LCC 1983. Retrieved 20 May 2025.

- ^ "The College Crest". The Royal College of Anaesthetists. 2014. Archived from the original on 12 September 2014. Retrieved 12 September 2014.

- ^ S. William Gunn; M. Masellis (2008). Concepts and practice of humanitarian medicine. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-387-72263-4.

institut de france and john snow.

Google Books - ^ Couvrier R, Edwards G (July 1959). "John Snow and the Institute of France". Med Hist. 3 (3): 249–251. doi:10.1017/s0025727300024662. PMC 1034490.

- ^ John Snow College

- ^ Remembering Dr. John Snow on the sesquicentennial of his death

- ^ Hempel, S. (2013). "John Snow". The Lancet. 381 (9874): 1269–1270. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60830-2. PMID 23589914. S2CID 5591843.

- ^ "John Snow Memorial, North Street Gardens – York Civic Trust". yorkcivictrust.co.uk. Retrieved 5 May 2022.

Sources

[edit]- Hempel, Sandra (2006). The Medical Detective: John Snow, Cholera, and the Mystery of the Broad Street Pump. Granta Books. ISBN 1862078424

- Johnson, Steven (2006). The Ghost Map: The Story of London's Most Terrifying Epidemic – and How it Changed Science, Cities and the Modern World. Riverhead Books. ISBN 1-59448-925-4

- Körner, T. W. (1996). The Pleasures of Counting, chapter 1. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-56823-4

- Morris, Robert D. (2007). The Blue Death. HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-073089-7

- Shapin, Steven (6 November 2006) [Electronic version]. "[1]". The New Yorker. Retrieved 10 November 2006

- Tufte, Edward (1997). Visual Explanations, chapter 2. Graphics Press. ISBN 0-9613921-2-6

Further reading

[edit]- Vinten-Johansen, Peter; Brody, Howard; Paneth, Nigel; Rachman, Stephen; Rip, Michael (2003). Cholera, Chloroform, and the Science of Medicine: A Life of John Snow. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199747887.

External links

[edit]- "On the Mode of Communication of Cholera" by John Snow, M.D. (1st ed., 1849)

- "On the Mode of Communication of Cholera" by John Snow, M.D. ("2nd edition, much enlarged", includes cholera map opposite p. 45)

- Short narrative film about John Snow

- UCLA site devoted to the life of John Snow

- Myth and reality regarding the Broad Street pump

- John Snow Society

- Source for Snow's letter to the Editor of the Medical Times and Gazette

- Interactive versions of the John Snow's Map of Board Street Cholera Outbreak

- John Snow’s cholera analysis data in modern GIS formats

- PredictionX: John Snow and the Cholera Epidemic of 1854 (a Harvard/edX MOOC)

- The John Snow Archive and Research Companion

John Snow

View on GrokipediaJohn Snow (15 March 1813 – 16 June 1858) was an English physician who advanced the fields of epidemiology and anesthesiology through empirical investigations into disease transmission and the safe administration of anesthetic agents.[1][2]

Born in York to a laborer's family, Snow apprenticed in medicine from age 14 and later qualified as a surgeon-apothecary, moving to London where he established a practice focused on respiratory physiology and public health.[1]

His rejection of the miasma theory of disease—positing that "bad air" caused illnesses like cholera—led to rigorous analysis of water supplies during epidemics; in 1849 and 1855, he published works arguing for contagion via contaminated water based on mortality data from different London water companies.[3][4]

During the 1854 Soho cholera outbreak, Snow mapped over 500 deaths, demonstrating a cluster around the Broad Street pump; statistical comparisons of attack rates among pump users versus others, along with tracing the likely contamination source to a nearby cesspool, provided causal evidence implicating the pump's water, though the epidemic was already waning when its handle was removed at his urging.[3][4]

In anesthesiology, Snow pioneered dosage calculations and inhalation devices for ether and chloroform, administering the latter to Queen Victoria for her last two confinements in 1853 and 1857, which helped legitimize its clinical use despite risks of respiratory depression.[2][1]

These contributions, grounded in first-hand data collection and physiological reasoning, laid foundational principles for modern public health interventions targeting environmental vectors of infection.[2][3]