Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

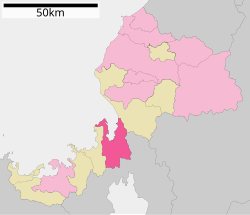

Tsuruga, Fukui

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

Tsuruga (敦賀市, Tsuruga-shi) is a city located in Fukui Prefecture, Japan. As of 29 June 2018[update], the city had an estimated population of 66,123 in 28,604 households and the population density of 260 persons per km2.[1] The total area of the city was 251.39 square kilometers (97.06 sq mi).

Geography

[edit]Tsuruga is located in central Fukui Prefecture, bordered by Shiga Prefecture to the south and Wakasa Bay of the Sea of Japan to the north. Tsuruga lies some 50 km south of Fukui, 90 km northwest of Nagoya, 40 km northwest of Maibara, 115 km northeast of Osaka, 75 km northeast of Kyoto, and 65 km east of Maizuru. Among cities on the Sea of Japan coast, Tsuruga is the nearest city to the Pacific Ocean. The distance between Tsuruga and Nagoya is only 115 km. Tsuruga and Nagoya are historically close to Shiga Prefecture and Kyoto.

Neighboring municipalities

[edit]- Fukui Prefecture

- Shiga Prefecture

Climate

[edit]Tsuruga has a humid subtropical climate (Köppen climate classification Cfa) with hot summers and cool winters. Precipitation is plentiful throughout the year, and is particularly heavy in December and January. The average annual temperature in Tsuruga is 15.6 °C (60.1 °F). The average annual rainfall is 2,199.5 mm (86.59 in) with December as the wettest month. The temperatures are highest on average in August, at around 27.7 °C (81.9 °F), and lowest in January, at around 4.7 °C (40.5 °F).[2]

| Climate data for Tsuruga (1991−2020 normals, extremes 1897−present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 18.9 (66.0) |

20.5 (68.9) |

24.5 (76.1) |

30.0 (86.0) |

33.2 (91.8) |

36.8 (98.2) |

37.6 (99.7) |

37.8 (100.0) |

36.7 (98.1) |

31.0 (87.8) |

26.1 (79.0) |

21.4 (70.5) |

37.8 (100.0) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 7.8 (46.0) |

8.5 (47.3) |

12.3 (54.1) |

17.8 (64.0) |

22.5 (72.5) |

25.8 (78.4) |

30.0 (86.0) |

31.9 (89.4) |

27.7 (81.9) |

22.2 (72.0) |

16.5 (61.7) |

10.7 (51.3) |

19.5 (67.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 4.7 (40.5) |

5.1 (41.2) |

8.3 (46.9) |

13.4 (56.1) |

18.2 (64.8) |

22.1 (71.8) |

26.3 (79.3) |

27.7 (81.9) |

23.7 (74.7) |

18.1 (64.6) |

12.7 (54.9) |

7.4 (45.3) |

15.6 (60.2) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 1.9 (35.4) |

1.8 (35.2) |

4.3 (39.7) |

9.1 (48.4) |

14.1 (57.4) |

18.8 (65.8) |

23.2 (73.8) |

24.5 (76.1) |

20.4 (68.7) |

14.4 (57.9) |

8.9 (48.0) |

4.2 (39.6) |

12.1 (53.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −10.9 (12.4) |

−10.5 (13.1) |

−9.6 (14.7) |

−1.7 (28.9) |

2.0 (35.6) |

7.9 (46.2) |

13.1 (55.6) |

14.1 (57.4) |

8.6 (47.5) |

2.7 (36.9) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

−6.2 (20.8) |

−10.9 (12.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 269.5 (10.61) |

164.7 (6.48) |

144.6 (5.69) |

120.4 (4.74) |

141.4 (5.57) |

144.1 (5.67) |

204.0 (8.03) |

146.9 (5.78) |

204.9 (8.07) |

152.6 (6.01) |

176.0 (6.93) |

316.7 (12.47) |

2,199.5 (86.59) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 54 (21) |

43 (17) |

7 (2.8) |

trace | 0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

19 (7.5) |

126 (50) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 21.8 | 17.3 | 14.4 | 11.6 | 10.7 | 10.7 | 12.2 | 9.3 | 11.3 | 11.7 | 14.1 | 20.7 | 165.8 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 1 cm) | 8.7 | 7.1 | 1.8 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3.1 | 20.8 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 73 | 71 | 67 | 66 | 68 | 74 | 75 | 72 | 74 | 72 | 71 | 73 | 71 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 62.6 | 81.2 | 131.7 | 166.3 | 184.4 | 139.8 | 153.1 | 202.2 | 147.6 | 145.1 | 111.5 | 72.6 | 1,598.1 |

| Source: Japan Meteorological Agency[3][2] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]Per Japanese census data,[4] the population of Tsuruga peaked around the year 2000 and has declined slightly since.

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1970 | 56,445 | — |

| 1980 | 61,844 | +9.6% |

| 1990 | 68,041 | +10.0% |

| 2000 | 68,145 | +0.2% |

| 2010 | 67,760 | −0.6% |

| 2020 | 64,264 | −5.2% |

History

[edit]Although Tsuruga promotes itself as the leading city of the "Wakasa region", the city is actually has always been of ancient Echizen Province. A settlement at Tsuruga is mentioned in the Nara period Kojiki and Nihon Shoki chronicles. Kanagasaki Castle was the site of major battles during the early Muromachi period and the Sengoku period, Under the Edo period Tokugawa shogunate, large portions of the city were part of the holdings of Obama Domain and Tsuruga Domain, and prospered as a major port on the kitamaebune shipping routes between western Japan and Hokkaido. Following the Meiji restoration, the area became part of Tsuruga District of Fukui Prefecture. With the creation of the modern municipalities system, the town of Tsuruga was founded on April 1, 1889.

An Imperial decree in July 1899 established Tsuruga as an open port for trading with the United States and the United Kingdom.[5]

Tsuruga merged with the neighboring village of Matsubara and was incorporated as a city on April 1, 1937. Tsuruga was the only Japanese port opened to the Polish orphans in 1920, and to the Jewish refugees in 1940 thanks to Jan Zwartendijk, the Dutch Consul in Kaunas, who issued visa for Curaçao and Surinam, Mr. Chiune Sugihara, Vice-Consul for the Empire of Japan in Lithuania who issued transit visa for Japan. These events are detailed at the Port of Humanity Tsuruga Museum. However, much of the city center was destroyed in 1945 during the Bombing of Tsuruga during World War II,

The city expanded on January 15, 1955 by annexing the neighboring villages of Arachi, Awano, Togo, Nakago and Higashiura.

Government

[edit]Tsuruga has a mayor-council form of government with a directly elected mayor and a unicameral city legislature of 26 members.

Economy

[edit]Tsuruga has a very healthy mixed economy focused on providing services to the Wakasa region, and also features a container port, a bulk terminal, a coal-fired power plant, two textile mills, a large furniture factory, a playground equipment manufacturer, and a Panasonic (Matsushita) facility. Education and energy research also drive the economy.

Tsuruga is also known for its two nuclear power facilities - the Monju demonstration nuclear plant and the Tsuruga Nuclear Power Plant.

Education

[edit]Tsuruga has 13 public elementary schools and five middle schools operated by the city government, and two public high schools operated by the Fukui Prefectural Board of Education. There is also one private high school and one private middle/high school. Tsuruga Nursing University is also located in the city.

Transportation

[edit]

Railway

[edit]High speed rail service to Tsuruga Station on the Hokuriku Shinkansen began on 16 March 2024.[6]

JR West - Hokuriku Shinkansen

JR West - Hokuriku Shinkansen

JR West - Hokuriku Main Line (Kosei Line)

JR West - Hokuriku Main Line (Kosei Line)

- Tsuruga, Shin-Hikida

JR West - Obama Line

JR West - Obama Line

- Hapi-line Fukui

- Tsuruga

Highway

[edit]Seaport

[edit]Air

[edit]The city does not have its own airport. The nearest airports are:

- Komatsu Airport, located 106 km (66 mi) north east.

- Chubu Centrair International Airport, located 117 km (73 mi) south east.

Sister cities

[edit]

Donghae, South Korea, since April 13, 1981

Donghae, South Korea, since April 13, 1981 Nakhodka, Primorsky Krai, Russia, since October 11, 1982

Nakhodka, Primorsky Krai, Russia, since October 11, 1982 Taizhou, Zhejiang, China, since November 13, 2001

Taizhou, Zhejiang, China, since November 13, 2001

Local attractions

[edit]- Grave of Takeda Kounsai, a National Historic Site

- Kanagasaki Castle site, a National Historic Site

- Kanegasaki-gū, a Shinto shrine

- Kehi Shrine, a large shrine complex built in 702. It hosts Kehi festival every year. Kehi shrine was also visited by the poet Matsuo Basho in 1689.[7]

- Nakagō Kofun Cluster, a National Historic Site

- Port of Humanity Tsuruga Museum, local history museum dedicated to the 20th century arrivals of Polish orphans and Jewish refugees

- Tsuruga Red Brick Warehouse, Meiji-period port building

- About twenty or so bronze statues – each perhaps four or five feet tall – of characters and scenes from the popular 1970s anime Uchū Senkan Yamato (Space Battleship Yamato or, in the United States, Star Blazers) and Galaxy Express 999 were erected in the city's downtown area in 1999. Though the creator of these shows, Leiji Matsumoto, was born elsewhere, an exhibit of his artwork was held in the city in 1999 as part of the city's 100th anniversary celebration, accompanied by the erection of the statues.

References

[edit]- ^ "Official website of Tjsugaru City" (in Japanese). Japan: Awara City. Retrieved July 5, 2018.

- ^ a b 気象庁 / 平年値(年・月ごとの値). JMA. Retrieved April 2, 2022.

- ^ 観測史上1~10位の値(年間を通じての値). JMA. Retrieved April 2, 2022.

- ^ Tsuruga population statistics

- ^ US Department of State. (1906). A digest of international law as embodied in diplomatic discussions, treaties and other international agreements (John Bassett Moore, ed.), Vol. 5, p. 759.

- ^ "Hokuriku Shinkansen's Kanazawa-Tsuruga extension set to open Saturday". The Japan Times. March 14, 2024. Archived from the original on March 14, 2024. Retrieved March 16, 2024.

- ^ "Kehi Jingu Shrine, Tsuruga Guide | Tsuruga Tourism Association".

.

External links

[edit]- Official website (in Japanese)

- (in Japanese) Galaxy Express 999 and Space Battleship Yamato statues in Tsuruga

Geographic data related to Tsuruga, Fukui at OpenStreetMap

Geographic data related to Tsuruga, Fukui at OpenStreetMap

Tsuruga, Fukui

View on GrokipediaGeography

Location and Topography

Tsuruga occupies the southwestern portion of Fukui Prefecture along the Sea of Japan coast, specifically fronting Tsuruga Bay, a sub-bay of Wakasa Bay.[7] The city is positioned where the Japanese main island narrows, approximately 100 kilometers north of Kyoto, serving as a strategic coastal gateway in the Hokuriku region.[1] Its geographic coordinates center around 35°39′N latitude and 136°04′E longitude.[8] The municipality spans 251.4 square kilometers, encompassing both urban coastal zones and inland terrain.[9] Topographically, Tsuruga consists primarily of low-lying coastal plains at elevations averaging 7 meters above sea level, facilitating its role as a port hub.[10] Inland areas rise gradually to wooded hills and surrounding mountains, including elevations reaching hundreds of meters, which divide the city from northern prefectural regions.[11] The western shore of Tsuruga Bay features sandy beaches backed by pine groves, such as Kehi-no-Matsubara, contrasting with the more industrialized eastern shoreline.[12] This coastal-mountainous interface influences local land use, with flat bayside areas supporting port facilities and urban development, while elevated terrains preserve forests and limit extensive inland expansion.[13]Climate

Tsuruga experiences a humid subtropical climate (Köppen classification Cfa), marked by hot, humid summers and cool winters with notable snowfall due to orographic lift from moist Sea of Japan air masses encountering nearby mountains. Annual average temperatures hover around 13 °C (55 °F), with seasonal extremes ranging from highs near 30 °C (86 °F) in August to lows approaching -1 °C (30 °F) in January. Precipitation totals approximately 2,350 mm (93 inches) yearly, distributed relatively evenly but peaking in summer months amid frequent typhoon influences.[14][15] Summers, spanning late June to mid-September, bring oppressive humidity and mostly cloudy skies, fostering conditions conducive to mold and discomfort. Winters, from early December to mid-March, turn windy and partly cloudy, with persistent snow cover from late December to late February; average monthly snowfall peaks at about 5 cm (2 inches) in January, though interannual variability can yield much heavier accumulations from Siberian high-pressure systems channeling cold, moist airflow. Spring and autumn serve as transitional periods with moderate temperatures but still elevated rainfall, occasionally disrupted by early or late cold snaps.[15][16] The table below summarizes monthly average high and low temperatures (in °C) and precipitation (in mm), derived from long-term observations:| Month | High (°C) | Low (°C) | Precipitation (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| January | 7 | -1 | 97 |

| February | 7 | 2 | 97 |

| March | 11 | 5 | 122 |

| April | 17 | 10 | 122 |

| May | 22 | 15 | 140 |

| June | 25 | 19 | 170 |

| July | 29 | 23 | 185 |

| August | 30 | 24 | 160 |

| September | 26 | 20 | 200 |

| October | 21 | 14 | 160 |

| November | 15 | 8 | 130 |

| December | 10 | 3 | 110 |

Seismic and Geological Features

Tsuruga occupies a coastal position along Wakasa Bay in Fukui Prefecture, underlain primarily by sedimentary rocks of the Mino-Tamba terrane, which include sandstones, shales, and minor greenstones intruded by Early Miocene igneous bodies such as plutonic rocks and dike swarms.[17] Surface geology features Quaternary deposits, including talus accumulations with limited internal structure and intercalated silt layers containing humic matter, indicative of depositional environments influenced by local erosion and marine processes.[18] The subsurface, as revealed by drilling data along regional infrastructure like expressways, consists of layered sediments reflecting Holocene and Pleistocene activity, with granitic intrusions such as the Tsuruga Body contributing to the area's lithological diversity from Eocene formations onward.[19][20] Seismically, Tsuruga lies within a tectonically active zone on the Japan Sea side of Honshu, experiencing a very high level of earthquake frequency, with approximately 1,500 events of varying magnitudes recorded annually in proximity to the city.[21] This activity stems from regional fault systems linked to the broader subduction dynamics of the Philippine Sea Plate, with at least two historical earthquakes exceeding magnitude 7 since 1900.[22] Notable hazards include potential rupture along nearby active faults, as evidenced by extensive evaluations at the Tsuruga Nuclear Power Plant site, where features like the D-1 crushed rock zone and adjacent K Fault have been assessed for Quaternary displacement, prompting concerns over their potential to generate strong ground motions.[23][24] In September 2024, Japan's Nuclear Regulation Authority endorsed findings that the Tsuruga-2 reactor site fails to satisfy post-Fukushima safety criteria due to unresolved geological ambiguities and seismic vibration risks from these faults, underscoring the challenges in confirming fault dormancy amid complex soil layering and historical seismic belts extending over 160 km in the prefecture.[25][26] The 1948 Fukui earthquake (magnitude 7.1), part of this seismic belt, exemplifies the region's capacity for destructive inland events that propagate coastal shaking and secondary hazards like tsunamis from Sea of Japan sources.[27]Demographics

Population Dynamics

As of the 2020 Japanese national census, Tsuruga's population stood at 64,264 residents, comprising 31,785 males and 32,479 females.[28] This marked a decrease of 1,901 individuals, or 2.9%, from the 66,165 recorded in the 2015 census.[28] The annual rate of decline averaged approximately -0.58% between 2015 and 2020.[29] Historical trends indicate a pattern of stagnation followed by contraction, with earlier census figures showing around 67,800 residents circa 2010 before the onset of more pronounced decreases.[30] This trajectory aligns with depopulation observed in many provincial Japanese cities, driven primarily by structural factors such as sub-replacement fertility rates—nationally around 1.3 births per woman in recent years—and net out-migration of working-age individuals seeking employment in larger urban centers.[9] Local economic reliance on port activities and energy infrastructure has not offset these pressures, as younger cohorts depart for opportunities elsewhere, exacerbating the loss of human capital in non-metropolitan areas.[31] Demographic composition in 2020 reflected an aging society, with roughly 49.5% male residents and 1.2% foreign nationals.[9] The age structure skewed toward older groups: individuals aged 65 and above constituted about 29.4% of the total, surpassing the national average and underscoring vulnerability to further shrinkage absent immigration or policy interventions to retain youth.[9] Detailed breakdowns showed concentrations in the 40-49 (8,982 persons) and 60-69 (8,592 persons) cohorts, indicative of a post-war baby boom generation entering retirement.[9]| Year | Population | 5-Year Change |

|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 66,165 | - |

| 2020 | 64,264 | -1,901 (-2.9%) |