Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

X-ray tube

View on Wikipedia

An X-ray tube is a vacuum tube that converts electrical input power into X-rays.[1] The availability of this controllable source of X-rays created the field of radiography, the imaging of partly opaque objects with penetrating radiation. In contrast to other sources of ionizing radiation, X-rays are only produced as long as the X-ray tube is energized. X-ray tubes are also used in CT scanners, airport luggage scanners, X-ray crystallography, material and structure analysis, and for industrial inspection.

Increasing demand for high-performance computed tomography (CT) scanning and angiography systems has driven development of very high-performance medical X-ray tubes.

History

[edit]X-ray tubes evolved from experimental Crookes tubes with which X-rays were first discovered on November 8, 1895, by the German physicist Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen. The first-generation cold cathode or Crookes X-ray tubes were used until the 1920s. These tubes work by ionisation of residual gas within the tube. The positive ions bombard the cathode of the tube to release electrons, which are accelerated toward the anode and produce X-rays when they strike it.[2] The Crookes tube was improved by William Coolidge in 1913.[3] The Coolidge tube, also called a hot cathode tube, uses thermionic emission, where a tungsten cathode is heated to a sufficiently high temperature to emit electrons, which are then accelerated toward the anode in a near perfect vacuum.[2]

Until the late 1980s, X-ray generators were merely high-voltage, AC to DC variable power supplies. In the late 1980s a different method of control was emerging, called high-speed switching. This followed the electronics technology of switching power supplies (aka switch mode power supply), and allowed for more accurate control of the X-ray unit, higher quality results and reduced X-ray exposures.[citation needed]

Physics

[edit]

As with any vacuum tube, there is a cathode, which emits electrons into the vacuum and an anode to collect the electrons, thus establishing a flow of electrical current, known as the beam, through the tube. A high voltage power source, for example 30 to 150 kilovolts (kV), called the tube voltage, is connected across cathode and anode to accelerate the electrons. The X-ray spectrum depends on the anode material and the accelerating voltage.[4]

Electrons from the cathode collide with the anode material, usually tungsten, molybdenum or copper, and accelerate other electrons, ions and nuclei within the anode material. About 1% of the energy generated is emitted/radiated, usually perpendicular to the path of the electron beam, as X-rays. The rest of the energy is released as heat. Over time, tungsten will be deposited from the target onto the interior surface of the tube, including the glass surface. This will slowly darken the tube and was thought to degrade the quality of the X-ray beam. Vaporized tungsten condenses on the inside of the envelope over the "window" and thus acts as an additional filter and decreases the tube's ability to radiate heat.[5] Eventually, the tungsten deposit may become sufficiently conductive that at high enough voltages, arcing occurs. The arc will jump from the cathode to the tungsten deposit, and then to the anode. This arcing causes an effect called "crazing" on the interior glass of the X-ray window. With time, the tube becomes unstable even at lower voltages and must be replaced. At this point, the tube assembly (also called the "tube head") is removed from the X-ray system, and replaced with a new tube assembly. The old tube assembly is shipped to a company that reloads it with a new X-ray tube.[citation needed]

The two X-ray photon-generating effects are generally called the 'Characteristic effect' and the bremsstrahlung effect, a compound of the German bremsen meaning to brake, and Strahlung meaning radiation.[6]

The range of photonic energies emitted by the system can be adjusted by changing the applied voltage, and installing aluminum filters of varying thicknesses. Aluminum filters are installed in the path of the X-ray beam to remove "soft" (non-penetrating) radiation. The number of emitted X-ray photons, or dose, are adjusted by controlling the current flow and exposure time.[citation needed]

Heat released

[edit]Heat is produced in the focal spot of the anode. Since a small fraction (less than or equal to 1%) of electron energy is converted to X-rays, it can be ignored in heat calculations.[7] The quantity of heat produced (in Joule) in the focal spot is given by :

- being the waveform factor

- = peak AC voltage (in kilo Volts)

- = tube current (in milli Amperes)

- = exposure time (in seconds)

Heat Unit (HU) was used in the past as an alternative to Joule. It is a convenient unit when a single-phase power source is connected to the X-ray tube.[7] With a full-wave rectification of a sine wave, =, thus the heat unit:

- 1 HU = 0.707 J

- 1.4 HU = 1 J[8]

Types

[edit]Crookes tube (cold cathode tube)

[edit]

Crookes tubes generated the electrons needed to create X-rays by ionization of the residual air in the tube, instead of a heated filament, so they were partially but not completely evacuated. They consisted of a glass bulb with around 10−6 to 5×10−8 atmospheric pressure of air (0.1 to 0.005 Pa). They had an aluminum cathode plate at one end of the tube, and a platinum anode target at the other end. The anode surface was angled so that the X-rays would radiate through the side of the tube. The cathode was concave so that the electrons were focused on a small (~1 mm) spot on the anode, approximating a point source of X-rays, which resulted in sharper images. The tube had a third electrode, an anticathode connected to the anode. It improved the X-ray output, but the method by which it achieved this is not understood. A more common arrangement used a copper plate anticathode (similar in construction to the cathode) in line with the anode such that the anode was between the cathode and the anticathode.[citation needed]

To operate, a DC voltage of a few kilovolts to as much as 100 kV was applied between the anodes and the cathode, usually generated by an induction coil, or for larger tubes, an electrostatic machine.[citation needed]

Crookes tubes were unreliable. As time passed, the residual air would be absorbed by the walls of the tube, reducing the pressure. This increased the voltage across the tube, generating 'harder' X-rays, until eventually the tube stopped working. To prevent this, 'softener' devices were used (see picture). A small tube attached to the side of the main tube contained a mica sleeve or chemical that released a small amount of gas when heated, restoring the correct pressure.[citation needed]

The glass envelope of the tube would blacken with usage due to the X-rays affecting its structure.[citation needed]

Coolidge tube (hot cathode tube)

[edit]

- C: filament/cathode (-)

- A: anode (+)

- Win and Wout: water inlet and outlet of the cooling device

In the Coolidge tube, the electrons are produced by thermionic effect from a tungsten filament heated by an electric current. The filament is the cathode of the tube. The high voltage potential is between the cathode and the anode, the electrons are thus accelerated, then hit the anode.[citation needed]

There are two designs: end-window tubes and side-window tubes. End window tubes usually have "transmission target" which is thin enough to allow X-rays to pass through the target (X-rays are emitted in the same direction as the electrons are moving.) In one common type of end-window tube, the filament is around the anode ("annular" or ring-shaped), the electrons have a curved path (half of a toroid).[citation needed]

What is special about side-window tubes is an electrostatic lens is used to focus the beam onto a very small spot on the anode. The anode is specially designed to dissipate the heat and wear resulting from this intense focused barrage of electrons. The anode is precisely angled at 1-20 degrees off perpendicular to the electron current to allow the escape of some of the X-ray photons which are emitted perpendicular to the direction of the electron current. The anode is usually made of tungsten or molybdenum. The tube has a window designed for escape of the generated X-ray photons.[citation needed]

The power of a Coolidge tube usually ranges from 0.1 to 18 kW.[citation needed]

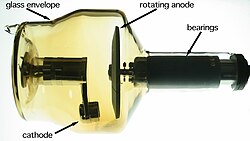

Rotating anode tube

[edit]

- A: Anode

- C: cathode

- T: Anode target

- W: X-ray window

A considerable amount of heat is generated in the focal spot (the area where the beam of electrons coming from the cathode strike to) of a stationary anode. Rather, a rotating anode lets the electron beam sweep a larger area of the anode, thus redeeming the advantage of a higher intensity of emitted radiation, along with reduced damage to the anode compared to its stationary state.[9]

The focal spot temperature can reach 2,500 °C (4,530 °F) during an exposure, and the anode assembly can reach 1,000 °C (1,830 °F) following a series of large exposures. Typical anodes are a tungsten-rhenium target on a molybdenum core, backed with graphite. The rhenium makes the tungsten more ductile and resistant to wear from the impact of the electron beams. The molybdenum conducts heat from the target. The graphite provides thermal storage for the anode, and minimizes the rotating mass of the anode.

Microfocus X-ray tube

[edit]Some X-ray examinations (such as, e.g., non-destructive testing and 3-D microtomography) need very high-resolution images and therefore require X-ray tubes that can generate very small focal spot sizes, typically below 50 μm in diameter. These tubes are called microfocus X-ray tubes.[citation needed]

There are two basic types of microfocus X-ray tubes: solid-anode tubes and metal-jet-anode tubes.[citation needed]

Solid-anode microfocus X-ray tubes are in principle very similar to the Coolidge tube, but with the important distinction that care has been taken to be able to focus the electron beam into a very small spot on the anode. Many microfocus X-ray sources operate with focus spots in the range 5-20 μm, but in the extreme cases spots smaller than 1 μm may be produced.[citation needed]

The major drawback of solid-anode microfocus X-ray tubes is their very low operating power. To avoid melting the anode, the electron-beam power density must be below a maximum value. This value is somewhere in the range 0.4-0.8 W/μm depending on the anode material.[10] This means that a solid-anode microfocus source with a 10 μm electron-beam focus can operate at a power in the range 4-8 W.

In metal-jet-anode microfocus X-ray tubes the solid metal anode is replaced with a jet of liquid metal, which acts as the electron-beam target. The advantage of the metal-jet anode is that the maximum electron-beam power density is significantly increased. Values in the range 3-6 W/μm have been reported for different anode materials (gallium and tin).[11][12] In the case with a 10 μm electron-beam focus a metal-jet-anode microfocus X-ray source may operate at 30-60 W.

The major benefit of the increased power density level for the metal-jet X-ray tube is the possibility to operate with a smaller focal spot, say 5 μm, to increase image resolution and at the same time acquire the image faster, since the power is higher (15-30 W) than for solid-anode tubes with 10 μm focal spots.

Hazards of X-ray production from vacuum tubes

[edit]

Any vacuum tube operating at several thousand volts or more can produce X-rays as an unwanted byproduct, raising safety issues.[13][14] The higher the voltage, the more penetrating the resulting radiation and the more the hazard. CRT displays, once common in color televisions and computer displays, operate at 3-40 kilovolts depending on size,[15] making them the main concern among household appliances. Historically, concern has focused less on the CRT, since its thick glass envelope is impregnated with several pounds of lead for shielding, than on high voltage (HV) rectifier and voltage regulator tubes inside earlier TVs. In the late 1960s it was found that a failure in the HV supply circuit of some General Electric TVs could leave excessive voltages on the regulator tube, causing it to emit X-rays. The same failure mode was also observed in early revisions of Soviet-made Rubin TVs equipped with GP-5 voltage-regulator tube. The models were recalled and the ensuing scandal caused the US agency responsible for regulating this hazard, the Center for Devices and Radiological Health of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), to require that all TVs include circuits to prevent excessive voltages in the event of failure.[16] The hazard associated with excessive voltages was eliminated with the advent of all-solid-state TVs, which have no tubes other than the CRT. Since 1969, the FDA has limited TV X-ray emission to 0.5 mR (milliroentgen) per hour. As other screen technologies advanced, starting in the 1990s, the production of CRTs was slowly phased out. These other technologies, such as LED, LCD and OLED, are incapable of producing x-rays due to the lack of a high voltage transformer.[17]

See also

[edit]Patents

[edit]- Coolidge, U.S. patent 1,211,092, "X-ray tube"

- Langmuir, U.S. patent 1,251,388, "Method of and apparatus for controlling X-ray tubes

- Coolidge, U.S. patent 1,917,099, "X-ray tube"

- Coolidge, U.S. patent 1,946,312, "X-ray tube"

References

[edit]- ^ Behling, Rolf (2015). Modern Diagnostic X-Ray Sources, Technology, Manufacturing, Reliability. Boca Raton, FL, USA: Taylor and Francis, CRC Press. ISBN 9781482241327.

- ^ a b Mould, Richard F. (2017-12-29). "William David Coolidge (1873–1975). Biography with special reference to X-ray tubes". Nowotwory. Journal of Oncology. 67 (4): 273–280. doi:10.5603/NJO.2017.0045. ISSN 2300-2115. Archived from the original on 2023-01-17. Retrieved 2023-01-17.

- ^ Coolidge, U.S. patent 1,203,495. Priority date May 9, 1913.

- ^ "X-ray and Elemental-Analysis". www.bruker.com. Archived from the original on February 23, 2008.

- ^ John G. Stears; Joel P. Felmlee; Joel E. Gray (September 1986), "cf., Half-Value-Layer Increase Owing to Tungsten Buildup in the X-ray Tube: Fact or Fiction", Radiology, 160 (3): 837–838, doi:10.1148/radiology.160.3.3737925, PMID 3737925

- ^ "An Etymological Dictionary of Astronomy and Astrophysics - English-French-Persian". dictionary.obspm.fr. Retrieved 2024-08-23.

- ^ a b Sprawls, Perry. "X-Ray Tube Heating and Cooling". The Physical Principles of Medical Imaging. Archived from the original on 2021-12-01. Retrieved 2019-05-19.

- ^ Perry Sprawls, Ph.D. X-Ray Tube Heating and Cooling Archived 2021-12-01 at the Wayback Machine, from The web-based edition of The Physical Principles of Medical Imaging, 2nd Ed.

- ^ "X-ray tube". Archived from the original on 2021-12-01. Retrieved 2019-05-19.

- ^ D. E. Grider, A Wright, and P. K. Ausburn (1986), "Electron beam melting in microfocus x-ray tubes", J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 19: 2281-2292

- ^ M. Otendal, T. Tuohimaa, U. Vogt, and H. M. Hertz (2008), "A 9 keV electron-impact liquid-gallium-jet x-ray source", Rev. Sci. Instrum. 79: 016102

- ^ T. Tuohimaa, M. Otendal, and H. M. Hertz (2007), "Phase-contrast x-ray imaging with a liquid-metal-jet-anode microfocus source", Appl. Phys. Lett. 91: 074104

- ^ "We want you to know about television radiation". Center for Devices and Radiological Health, US FDA. 2006. Archived from the original on December 18, 2007. Retrieved 2007-12-24.

- ^ Pickering, Martin. "An informal history of X-ray protection". sci.electronics.repair FAQ. Archived from the original on 2012-02-07. Retrieved 2007-12-24.

- ^ Hong, Michelle. "Voltage of a Television Picture Tube". Archived from the original on 21 October 2000. Retrieved 11 August 2016.

- ^ Murray, Susan (2018-09-23). "When Televisions Were Radioactive". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 2021-01-12. Retrieved 2020-12-11.

- ^ Health, Center for Devices and Radiological (February 9, 2019). "Television Radiation". FDA – via www.fda.gov.

External links

[edit]- X-ray Tube - A Radiograph of an X-ray Tube

- The Cathode Ray Tube site

- NY State Society of Radiologic Sciences

- Collection of X-ray tubes by Grzegorz Jezierski of Poland

- Excillum AB, a manufacturer of metal-jet-anode microfocus x-ray tubes

- Example of how X-ray tubes work.