Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

| Umay | |

|---|---|

Goddess of Newborn Children and Souls | |

| Abode | Sky |

| Gender | Female |

| Ethnic group | Turkic peoples |

| Genealogy | |

| Siblings | Erlik Koyash Ay Tanrı Ülgen |

| Spouse | Tengri |

| Turkic mythology |

|---|

|

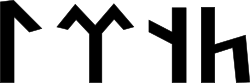

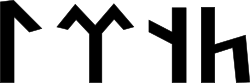

Umay (also known as Umai; Old Turkic: 𐰆𐰢𐰖; Kazakh: Ұмай ана, Ūmai ana; Uzbek: Umay ona; Kyrgyz: Умай эне, Umay ene; Turkish: Umay Ana) is the goddess of fertility in Turkic mythology and Tengrism and as such related to women, mothers, and children.[1] Umay not only protects and educates babies, but also may separate the soul from the dead, especially young children. She lives in heaven and is invisible to the common people. Souls of babies-to-be-born are kept in her "temple" of Mount Ymay-tas or Amay. The Khakas emphasize her in particular.[2] From Umai, the essence of fire (Od Ana) was born.[3]

Etymology

[edit]The Turkic word umāy originally meant "placenta, afterbirth" and this word was used as the name for the goddess whose function was to look after women and children, and she is associated with fertility.[4][5] In Mongolian, Umai means "womb" or "uterus", possibly reflecting acculturation of Mongols by Turks or ancient lexical ties between Mongols and Turks.[6] Similar phenomenon is observed in Japanese 生まれ umare "birth",[7] seemingly cognate with Old English umba "child" ~ Old English womb "belly, uterus" (of unknown origin),[8] all together offering an *(h)um-, *(kw)um- or *(k)uŋ- "to give birth, act of parturition; [secondary, mythologically] to bring life forth" as a subject for a linguistic research.

Goddess of children

[edit]The name appears in the 8th century inscription of Kul Tigin in the phrase Umay teg ögüm katun kutıŋa "under the auspices of my mother who is like the goddess Umay".

Umay is a protector of women and children. The oldest evidence is seen in the Orkhon script monuments. From these it is understood that Umay was accepted as a mother and a guide. Also, khagans were thought to represent Kök Tengri. Khagan wives, katuns or hatuns, were considered Umays, too. With the help of 'Umay, katuns had babies and these babies were the guarantee of the empire. According to Divanü Lügat’it-Türk, when women worship Umay, they have male babies. Turkic women tie strings attached with small cradles to will a baby from Umay. This belief can be seen with the Tungusic peoples in southern Siberia and the Altay people. Umay is always depicted together with a child. There are only rare exceptions to this. It is believed that when Umay leaves a child for a long time, the child gets ill and shamans are involved to call Umay back. The smiling of a sleeping baby shows Umay is near it and crying means that Umay has left.[9]

Potapov states that, as protector of babies, deceased children are taken by Umai to the heavens.[10]

In the view of the Kyrgyz people, Umay not only protects children, but also Turkic communities around the world. At the same time Umay helps people to obtain more food and goods and gives them luck.

As Umay is associated with the sun, she is called Sarı Kız 'Yellow Maiden', and yellow is her color and symbol. She is depicted as having sixty golden tresses that look like the rays of the sun. She is thought to have once been identical with Od iyesi. Umay and Ece are also used as female given names in the Republic of Turkey.

Umay's representation of childbirth, growth and her connection to nature is also presented in Turkish culture today in a tree called "The Umay Nine Trees" at the Teos Archaeological Site. "Amidst these remnants of human endeavor, a silent guardian of nature and the circle of life stands tall – an olive tree believed to be nearly 1,800 years old, named after Umay Nine (Nana Umay), one of the most enduring figures of Anatolian and Central Asian mythologies."[11]

References

[edit]- ^ Cotterell, Arthur; Rachel Storm (1999). The Ultimate Encyclopedia of Mythology. New York: Lorenz Books. pp. 466, 481. ISBN 0-7548-0091-1.

- ^ Funk, Dmitriy (2018). "Siberian Cosmologies". The International Encyclopedia of Anthropology. Callan, Hilary (ed). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. pp. 3-4. doi:10.1002/9781118924396.wbiea2237.

- ^ Sultanova, Razia. From shamanism to Sufism: women, Islam and culture in Central Asia. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2011.

- ^ Slovic, Scott; Rangarajan, Swarnalatha; Sarveswaran, Vidya (1 February 2019). Routledge Handbook of Ecocriticism and Environmental Communication. Routledge. p. 471. ISBN 978-1-351-68269-5.

- ^ Clauson, Gerard (1972). An Etymological Dictionary of Pre-Thirteenth Century Turkish. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 164–165.

- ^ Sinor, Denis (1997). Studies in Medieval Inner Asia. Ashgate. p. 159. ISBN 978-0-86078-632-0.

one wonders whether the agreement between the Turkic proper name and the Mongol word umay "womb", placenta" is the result of an incorporation of Turkic elements into Mongol ethnicity or should be viewed as an ancient, lexical heritage shared by Turks and Mongols.

- ^ "umare". Takomoto - Japanese dictionary and Nihongo study tool. Retrieved 2025-06-22.

- ^ "Womb - Etymology, Origin & Meaning". etymonline. Retrieved 2025-06-22.

- ^ Каратаев, О., and Е. Умаралиев. "CULT UMAI-ENE AMONG THE KYRGYZ." Вестник КазНУ. Серия историческая 90.3 (2018): 4-8.

- ^ Каратаев, О., and Е. Умаралиев. "CULT UMAI-ENE AMONG THE KYRGYZ." Вестник КазНУ. Серия историческая 90.3 (2018): 4-8.

- ^ "Nature's Ancient Embrace: Unveiling The Umay Nine Tree at Teos | Turkish Museums". Turkish Museum. 2024-05-10. Retrieved 2025-05-05.

External links

[edit]- Kuyash ham Alav (Sun is also Fire) Archived 2011-12-30 at the Wayback Machine

Bibliography

[edit]- Özhan Öztürk. Folklor ve Mitoloji Sözlüğü. Ankara, 2009 Phoenix Yayınları. s. 491 ISBN 978-605-5738-26-6 (in Turkish)