Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Khakas

View on WikipediaYou can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Russian. (April 2009) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

The Khakas or Khakass[a] are a Turkic indigenous people of Siberia, who live in the republic of Khakassia, Russia. They speak the Khakas language.

Key Information

The Khakhassian people are direct descendants of various ancient cultures that have inhabited southern Siberia, including the Andronovo culture, Samoyedic peoples, the Tagar culture, and the Yenisei Kyrgyz culture,[6][7][8] although some populations traditionally called Khakhassian are not related to Khakhassians or any other ethnic group present in the area.[9]

Etymology

[edit]The Khakas people were historically known as Kyrgyz, before being labelled as Tatars by the Imperial Russians following the conquest of Siberia. The name Tatar then became the autonym used by the Khakas to refer to themselves, in the form Tadar. Following the Russian Revolution, the Soviet authorities changed the name of the group to Khakas, a newly-formed name based on the Chinese name for the Kyrgyz people, Xiaqiasi.[10]

History

[edit]

The Yenisei Kyrgyz were made to pay tribute in a treaty concluded between the Dzungars and Russians in 1635.[11] The Dzungar Oirat Kalmyks coerced the Yenisei Kyrgyz into submission.[12][13]

Some of the Yenisei Kyrgyz were relocated into the Dzungar Khanate by the Dzungars, and then the Qing moved them from Dzungaria to northeastern China in 1761, where they became known as the Fuyu Kyrgyz.[14][15][16] Sibe Bannermen were stationed in Dzungaria while Northeastern China (Manchuria) was where some of the remaining Öelet Oirats were deported to.[17] The Nonni basin was where Oirat Öelet deportees were settled. The Yenisei Kyrgyz were deported along with the Öelet.[18] Chinese and Oirat replaced Oirat and Kyrgyz during Manchukuo as the dual languages of the Nonni-based Yenisei Kyrgyz.[19]

In the 17th century, the Khakas formed Khakassia in the middle of the lands of Yenisei Kyrgyz[citation needed], who at the time were vassals of a Mongolian ruler. The Russians arrived shortly after the Kyrgyz left, and an inflow of Russian agragian settlers began. In the 1820s, gold mines started to be developed around Minusinsk, which became a regional industrial center.

The names Khongorai and Khoorai were applied to the Khakas before they became known as the Khakas.[20][21][22][23] Khakas refer to themselves as Tadar.[24][25][26] Khoorai (Khorray) has also been in use to refer to them.[27][28][29] Now the Khakas call themselves Tadar[30][31] and do not use Khakas to describe themselves in their own language.[32] They are also called Abaka Tatars.[33]

During the 19th century, many Khakas accepted the Russian ways of life, and most were converted en masse to Russian Orthodox Christianity. Shamanism, however, is still common;.[34] Many Christians practice shamanism with Christianity.[35] In Imperial Russia, the Khakas used to be known under other names, used mostly in historic contexts: Minusinsk Tatars (Russian: минуси́нские тата́ры), Abakan Tatars (абака́нские тата́ры), and Yenisei Turks.

During the Revolution of 1905, a movement towards autonomy developed. When Soviets came to power in 1923, the Khakas National District was established, and various ethnic groups (Beltir, Sagai, Kachin, Koibal, and Kyzyl) were artificially "combined" into one—the Khakas. The National District was reorganized into Khakas Autonomous Oblast, a part of Krasnoyarsk Krai, in 1930.[36] The Republic of Khakassia in its present form was established in 1992.

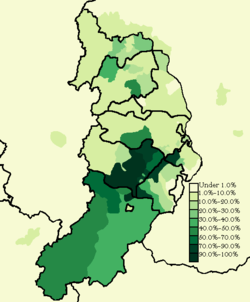

Khakas account for only about 12% of the total population of the republic (78,500 as of 1989 Census). Khakas traditionally practiced nomadic herding, agriculture, hunting, and fishing. The Beltir people specialized in handicraft as well. Herding sheep and cattle is still common, although the republic became more industrialized over time.

Genetics

[edit]Paternal lineages

[edit]Genetic research has identified 4 primary paternal lineages in the Khakhas population.[37][38]

- Haplogroup N is the predominant paternal haplogroup in the Khakhas population. It represents roughly 64% of Khakas male lineages, mainly N1b (P43) (around 44%) and N1c (M178) (around 20%). It has been proposed that haplogroup N1b (specifically N2a1-B478) in the Khakassians may represent descent from Samoyedic speakers who were assimilated by Turkic speakers.[39][40]

- Haplogroup R1a is the second most common haplogroup in Khakhas populations; representing 27.9-33% of the total. Haplogroup R1a has the predominant paternal haplogroup in the Altai region since the appearance of the Andronovo culture.[41] It represents a migration of Indo-European speakers who migrated east and settled in central Siberia in the Bronze and Iron Age periods, such as the Indo-Iranian Andronovo culture and the Tagar culture.[42]

Other paternal haplogroups in Khakassians include Haplogroup Q, which is probably the "original" Siberian lineage in Khakassians. It has a frequency of approximately 4.8% in the Khakassian population. Minor frequencies of haplogroups R1b, C3, and E1 were also reported.

Maternal lineages

[edit]Over 80% of Khakassian mtDNA lineages belong to East Eurasian lineages, although a significant percentage (18.9%) belong to various West Eurasian mtDNA lineages.[43]

Religion

[edit]At present, the Khakas predominantly are Orthodox Christians (Russian Orthodox Church).

Also there is traditional shamanism (Tengrism), including following movements:[44]

- Khakas Heritage Center—the Society of Traditional Religion of Khakas Shamanism "Ah-Chayan" (Russian: Центр хакасского наследия — общество традиционной религии хакасского шаманизма "Ах-Чаян");

- Traditional religion of the Khakas society "Izykh" (Russian: Общество традиционной религии хакасского народа "Изых");

- Traditional religion society "Khan Tigir" (Russian: Общество традиционной религии "Хан Тигир").

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Окончательные итоги Всероссийской переписи населения 2010 года". Archived from the original on 3 August 2011. (All Russian census, 2010)

- ^ State statistics committee of Ukraine - National composition of population, 2001 census (Ukrainian)

- ^ Lee & Kuang (2017) "A Comparative Analysis of Chinese Historical Sources and Y-DNA Studies with Regard to the Early and Medieval Turkic Peoples", Inner Asia 19. p. 216 of 197-239

- ^ Kara, Dávid Somfai (2018). "The Formation of Modern Turkic 'Ethnic' Groups in Central and Inner Asia". The Hungarian Historical Review. 7 (1): 98–110. ISSN 2063-8647. JSTOR 26571579.

The remaining Turkic clans (Yenisei Kyrgyz) were called the Tatars of Minusinsk by the Russians, and soon this became their autonym (tadarlar). In Soviet times, their official name (exonym) changed. They became Khakas after their Chinese name "xiaqiasi," or Kyrgyz.

- ^ Vadim Stepanov, "Genetic diversity of the Khakass gene pool: Subethnic differentiation and the structure of Y-chromosome haplogroups", Molecular Biology, vol. 45, no. 3, 2011, doi:10.1134/S0026893311020117

- ^ Khar’kov 2011, pp. 404–405

- ^ Carl Skutsch (7 November 2013). Encyclopedia of the World's Minorities. Routledge. pp. 705–. ISBN 978-1-135-19388-1.

- ^ Paul Friedrich (14 January 1994). Encyclopedia of World Cultures: Russia and Eurasia, China. G.K. Hall. ISBN 978-0-8161-1810-6.

- ^ Shtygasheva, Khamina. "Genetic diversity of the Khakass gene pool: Subethnic differentiation and the structure of Y-chromosome haplogroups".

- ^ Kara, Dávid Somfai (2018). "The Formation of Modern Turkic 'Ethnic' Groups in Central and Inner Asia". The Hungarian Historical Review. 7 (1): 98–110. ISSN 2063-8647. JSTOR 26571579.

The remaining Turkic clans (Yenisei Kyrgyz) were called the Tatars of Minusinsk by the Russians, and soon this became their autonym (tadarlar). In Soviet times, their official name (exonym) changed. They became Khakas after their Chinese name "xiajiasi," or Kyrgyz.

- ^ Millward 2007, p. 89.

- ^ Concise Encyclopedia of Languages of the World. Elsevier. 6 April 2010. pp. 611–. ISBN 978-0-08-087775-4.

- ^ E. K. Brown; R. E. Asher; J. M. Y. Simpson (2006). Encyclopedia of language & linguistics. Elsevier. p. 224. ISBN 978-0-08-044299-0.

- ^ Tchoroev (Chorotegin) 2003, p. 110.

- ^ Pozzi & Janhunen & Weiers 2006, p. 113.

- ^ Giovanni Stary; Alessandra Pozzi; Juha Antero Janhunen; Michael Weiers (2006). Tumen Jalafun Jecen Aku: Manchu Studies in Honour of Giovanni Stary. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 112–. ISBN 978-3-447-05378-5.

- ^ Juha Janhunen (1996). Manchuria: An Ethnic History. Finno-Ugrian Society. p. 112. ISBN 978-951-9403-84-7.

- ^ Juha Janhunen (1996). Manchuria: An Ethnic History. Finno-Ugrian Society. pp. 111–112. ISBN 978-951-9403-84-7.

- ^ Juha Janhunen (1996). Manchuria: An Ethnic History. Finno-Ugrian Society. p. 59. ISBN 978-951-9403-84-7.

- ^ Marjorie Mandelstam Balzer (1995). Culture Incarnate: Native Anthropology from Russia. M.E. Sharpe. pp. 75–. ISBN 978-1-56324-535-0.

- ^ Anthropology & Archeology of Eurasia. M.E. Sharpe Incorporated. 1994. p. 42.

- ^ Edward J. Vajda (29 November 2004). Languages and Prehistory of Central Siberia. John Benjamins Publishing Company. pp. 215–. ISBN 978-90-272-7516-5.

- ^ Sue Bridger; Frances Pine (11 January 2013). Surviving Post-Socialism: Local Strategies and Regional Responses in Eastern Europe and the Former Soviet Union. Routledge. pp. 55–. ISBN 978-1-135-10715-4.

- ^ Marjorie Mandelstam Balzer (1995). Culture Incarnate: Native Anthropology from Russia. M.E. Sharpe. pp. 71–. ISBN 978-1-56324-535-0.

- ^ Edward J. Vajda (29 November 2004). Languages and Prehistory of Central Siberia. John Benjamins Publishing Company. pp. 215–. ISBN 978-90-272-7516-5.

- ^ Canadian Review of Studies in Nationalism: Revue Canadienne Des Études Sur Le Nationalisme. University of Prince Edward Island. 1997. p. 149.

- ^ James B. Minahan (30 May 2002). Encyclopedia of the Stateless Nations: Ethnic and National Groups Around the World A-Z [4 Volumes]. ABC-CLIO. pp. 979–. ISBN 978-0-313-07696-1.

- ^ James Minahan (1 January 2002). Encyclopedia of the Stateless Nations: D-K. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 979–. ISBN 978-0-313-32110-8.

- ^ James B. Minahan (10 February 2014). Ethnic Groups of North, East, and Central Asia: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 140–. ISBN 978-1-61069-018-8.

- ^ Sue Bridger; Frances Pine (11 January 2013). Surviving Post-Socialism: Local Strategies and Regional Responses in Eastern Europe and the Former Soviet Union. Routledge. pp. 55–. ISBN 978-1-135-10715-4.

- ^ Folia orientalia. Państwowe Wydawn. Naukowe. 1994. p. 157.

- ^ Anthropology & Archeology of Eurasia. M.E. Sharpe Incorporated. 1994. p. 38.

- ^ Paul Friedrich (14 January 1994). Encyclopedia of World Cultures: Russia and Eurasia, China. G.K. Hall. p. 186. ISBN 978-0-8161-1810-6.

- ^ Stepanoff, Charles (January 2013). "Drums and virtual space in Khakas shamanism". Gradhiva. 17 (1): 144–169. doi:10.4000/gradhiva.2649.

- ^ Kira Van Deusen (2003). Singing Story, Healing Drum: Shamans and Storytellers of Turkic Siberia. McGill-Queen's University Press. pp. 8–9. ISBN 0-7735-2617-X.

- ^ James Forsyth (8 September 1994). A History of the Peoples of Siberia: Russia's North Asian Colony 1581-1990. Cambridge University Press. pp. 300–. ISBN 978-0-521-47771-0.

- ^ Xu & Li 2017, pp. 42–43

- ^ Khar’kov, V. N. (2011). "Genetic diversity of the Khakass gene pool: Subethnic differentiation and the structure of Y-chromosome haplogroups". Molecular Biology. 45 (3): 404–416. doi:10.1134/S0026893311020117. S2CID 37140960.

- ^ Khar’kov 2011, p. 407

- ^ Xu, Dan; Li, Hui (2017). Languages and Genes in Northwestern China and Adjacent Regions. Springer. p. 43. ISBN 978-981-10-4169-3. "From a generic perspective, N1b-P43 samples in Samoyed and Tuvan populations belong to a specific subclade named N2a1-B478. The expansion time of N2a1-B478 is only about 3600 years ago, as shown in Fig. 2. Hence, we propose that the southern part of Samoyed populations may have changed their language to a Turkic language at various historical periods, bringing haplogroup N2a1-B478 in to Tuvan, Khakhassian and Shors populations."

- ^ Xu & Li 2017, pp. 42–43

- ^ Khar’kov 2011, p. 413

- ^ Derenko, MV (September 2003). "Diversity of Mitochondrial DNA Lineages in South Siberia". Annals of Human Genetics. 67 (5): 400. doi:10.1046/j.1469-1809.2003.00035.x. PMID 12940914. S2CID 28678003.

- ^ Bourdeaux, Michael; Filatov, Sergei, eds. (2006). Современная религиозная жизнь России. Опыт систематического описания [Contemporary Religious Life of Russia. Systematic description experience] (in Russian). Vol. 4. Moscow: Keston Institute; Logos. pp. 124–129. ISBN 5-98704-057-4.

External links

[edit] Media related to Khakas people at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Khakas people at Wikimedia Commons- NUPI - Centre for Asian Studies profile

- The Sleeping Warrior: New Legends in the Rebirth of Khakass Shamanic Culture Archived 1 March 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- Abakan city streets views

- [1] Archived 20 June 2018 at the Wayback Machine Beyaz Arif Akbas, "Khakassia: The Lost Land", Portland State Center for Turkish Studies, 2007.

Khakas

View on GrokipediaThe Khakas (Khakas: Хакаслар; romanized: Xakaslar) are a Turkic indigenous people native to the Republic of Khakassia in southern Siberia, Russia, where they form the titular ethnic group.[1] Numbering around 67,000 individuals, they comprise approximately 12.7% of the republic's population according to official census figures.[1] Their ethnogenesis involves a historical fusion of various Turkic-speaking tribes, including Uyghur, Tuvan, and Yeniseian Kyrgyz elements, shaped by migrations and interactions in the Minusinsk Basin over centuries.[2]

The Khakas speak the Khakas language, classified within the Siberian branch of the Turkic language family, which exhibits vowel harmony and agglutinative structure typical of Turkic tongues, though facing endangerment with only about 40,000 speakers.[3][4] Traditionally pastoralists and hunters, the Khakas maintain elements of shamanism alongside Russian Orthodox Christianity, with their cultural heritage reflected in epic folklore, throat singing, and ancient petroglyph sites in the Sayan Mountains that attest to millennia of habitation.[5] The republic's autonomy, established in the Soviet era, preserves their distinct identity amid a predominantly Russian demographic.[1]