Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Cybele

View on Wikipedia| Cybele | |

|---|---|

Mother Goddess | |

| |

| Other names | Magna Mater |

| Major cult center | Athens, Rome, Ostia |

| Animals | Lions |

| Symbols | Mountains, conifer cones, tympanon |

| Temples | Metroons |

| Festivals | Megalesia, Hilaria |

| Consort | Attis |

Cybele (/ˈsɪbəliː/ SIB-ə-lee;[1] Phrygian: Matar Kubileya, Kubeleya 'Kubeleya Mother', perhaps 'Mountain Mother';[2] Lydian: Kuvava; Greek: Κυβέλη Kybélē, Κυβήβη Kybēbē, Κύβελις Kybelis) is an Anatolian mother goddess; she may have a possible forerunner in the earliest Neolithic at Çatalhöyük. She is Phrygia's only known goddess, and likely, its national deity.[3] Greek colonists in Asia Minor adopted and adapted her Phrygian cult and spread it to mainland Greece and to the more distant western Greek colonies around the sixth century BC.

In Greece, Cybele met with a mixed reception. She became partially assimilated to aspects of the Earth-goddess Gaia, of her possibly Minoan equivalent Rhea, and of the harvest–mother goddess Demeter. Some city-states, notably Athens, evoked her as a protector, but her most celebrated Greek rites and processions show her as an essentially foreign, exotic mystery-goddess who arrives in a lion-drawn chariot to the accompaniment of wild music, wine, and a disorderly, ecstatic following. Uniquely in Greek religion, she had a eunuch mendicant priesthood, the Galli.[4] Many of her Greek cults included rites to a divine Phrygian castrate shepherd-consort Attis, who was probably a Greek invention. In Greece, Cybele became associated with mountains, town and city walls, fertile nature, and wild animals, especially lions.

In Rome, Cybele became known as Magna Mater ("Great Mother"). The Roman state adopted and developed a particular form of her cult after the Sibylline oracle in 205 BC recommended her conscription as a key religious ally in Rome's second war against Carthage (218 to 201 BC). Roman mythographers reinvented her as a Trojan goddess, and thus an ancestral goddess of the Roman people by way of the Trojan prince Aeneas. As Rome eventually established hegemony over the Mediterranean world, Romanized forms of Cybele's cults spread throughout Rome's empire. Greek and Roman writers debated and disputed the meaning and morality of her cults and priesthoods, which remain controversial subjects in modern scholarship.

Anatolia

[edit]

No contemporary text or myth survives to attest the original character and nature of Cybele's Phrygian cult. She may have evolved from a statuary type found at Çatalhöyük in Anatolia, of a "corpulent and fertile" female figure accompanied by large felines, dated to the 6th millennium BC and identified by some as a mother goddess.[5] In Phrygian art of the 8th century BC, the cult attributes of the Phrygian mother-goddess include attendant lions, a bird of prey, and a small vase for her libations or other offerings.[6]

The inscription Matar Kubileya/Kubeleya[2] at a Phrygian rock-cut shrine, dated to the first half of the 6th century BC, is usually read as "Mother of the mountain", a reading supported by ancient classical sources,[2][7] and consistent with Cybele as any of several similar tutelary goddesses, each known as "mother" and associated with specific Anatolian mountains or other localities:[8] a goddess thus "born from stone".[9] She is ancient Phrygia's only known goddess,[10] the divine companion or consort of its mortal rulers, and was probably the highest deity of the Phrygian state. Her name, and the development of religious practices associated with her, may have been influenced by the Kubaba cult of the deified Sumerian queen Kubaba.[11]

In the 2nd century AD, the geographer Pausanias attests to a Magnesian (Lydian) cult to "the mother of the gods", whose image was carved into a rock-spur of Mount Sipylus. This was believed to be the oldest image of the goddess, and was attributed to the legendary Broteas.[12] At Pessinos in Phrygia, the mother goddess—identified by the Greeks as Cybele—took the form of an unshaped stone of black meteoric iron,[13] and may have been associated with or identical to Agdistis, Pessinos' mountain deity.[14][15] This was the aniconic stone that was removed to Rome in 204 BC.

Images and iconography in funerary contexts, and the ubiquity of her Phrygian name Matar ("Mother"), suggest that she was a mediator between the "boundaries of the known and unknown": the civilized and the wild, the worlds of the living and the dead.[16] Her association with hawks, lions, and the stone of the mountainous landscape of the Anatolian wilderness, seem to characterize her as mother of the land in its untrammeled natural state, with power to rule, moderate or soften its latent ferocity, and to control its potential threats to a settled, civilized life. Anatolian elites sought to harness her protective power to forms of ruler-cult; in Phrygia, the Midas monument connects her with king Midas, as her sponsor, consort, or co-divinity.[17] As protector of cities, or city states, she was sometimes shown wearing a mural crown, representing the city walls.[18] At the same time, her power "transcended any purely political usage and spoke directly to the goddess' followers from all walks of life".[19]

Some Phrygian shaft monuments are thought to have been used for libations and blood offerings to Cybele, perhaps anticipating by several centuries the pit used in her taurobolium and criobolium sacrifices during the Roman imperial era.[20] Over time, her Phrygian cults and iconography were transformed, and eventually subsumed, by the influences and interpretations of her foreign devotees, at first Greek and later Roman.

Greek Cybele

[edit]From around the 6th century BC, cults to the Anatolian mother-goddess were introduced from Phrygia into the ethnically Greek colonies of western Anatolia, mainland Greece, the Aegean islands and the westerly colonies of Magna Graecia. The Greeks called her Mātēr or Mētēr ("Mother"), or from the early 5th century Kubélē; in Pindar, she is "Mistress Cybele the Mother".[21] In Homeric Hymn 14 she is "the Mother of all gods and all human beings." Cybele was readily assimilated with several Greek goddesses, especially Rhea, as Mētēr theōn ("Mother of the gods"), whose raucous, ecstatic rites she may have acquired. As an exemplar of devoted motherhood, she was partly assimilated to the grain-goddess Demeter, whose torchlight procession recalled her search for her lost daughter, Persephone; but she also continued to be identified as a foreign deity, with many of her traits reflecting Greek ideas about barbarians and the wilderness, as Mētēr oreia ("Mother of the Mountains").[22] She is depicted as a Potnia Theron ("Mistress of animals"),[23] with her mastery of the natural world expressed by the lions that flank her, sit in her lap, or draw her chariot.[24] This schema may derive from a goddess figure from Minoan religion.[25] Walter Burkert places her among the "foreign gods" of Greek religion, a complex figure combining a putative Minoan-Mycenaean tradition with the Phrygian cult imported directly from Asia Minor.[26]

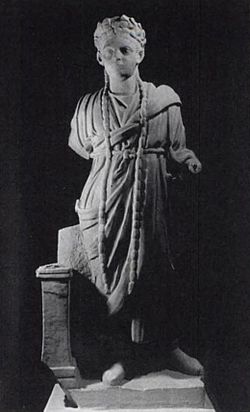

Cybele's early Greek images are small votive representations of her monumental rock-cut images in the Phrygian highlands. She stands alone within a naiskos, which represents her temple or its doorway, and is crowned with a polos, a high, cylindrical hat. A long, flowing chiton covers her shoulders and back. She is sometimes shown with lions in attendance. Around the 5th century BC, Agoracritos created a fully Hellenised and influential image of Cybele that was set up in the Metroon in the Athenian agora. It showed her enthroned, with a lion attendant, holding a phiale (a dish for making libations to the gods) and a tympanon (a hand drum). Both were Greek innovations to her iconography and reflect key features of her ritual worship introduced by the Greeks which would be salient in the cult's later development.[27][28]

For the Greeks, the tympanon was a marker of foreign cults, suitable for rites to Cybele, her close equivalent Rhea, and Dionysus; of these, only Cybele holds the tympanon. She appears with Dionysus, as a secondary deity in Euripides' Bacchae, 64 – 186, and Pindar's Dithyramb II.6 – 9. In the Bibliotheca formerly attributed to Apollodorus, Cybele is said to have cured Dionysus of his madness.[29]

Their cults shared several characteristics: the foreigner-deity arrived in a chariot, drawn by exotic big cats (Dionysus by tigers or panthers, Cybele by lions), accompanied by wild music and an ecstatic entourage of exotic foreigners and people from the lower classes. At the end of the 1st century BC Strabo notes that Rhea-Cybele's popular rites in Athens were sometimes held in conjunction with Dionysus' procession.[30] Both were regarded with caution by the Greeks, as being foreign,[31] to be simultaneously embraced and "held at arm's length".[32]

Cybele was also the focus of mystery cult, private rites with a chthonic aspect connected to hero cult and exclusive to those who had undergone initiation, although it is unclear who Cybele's initiates were.[33] Reliefs show her alongside young female and male attendants with torches, and with vessels for purification. Literary sources describe joyous abandonment to the loud, percussive music of tympanon, castanets, clashing cymbals, and flutes, and to the frenzied "Phrygian dancing", perhaps a form of circle-dancing by women, to the roar of "wise and healing music of the gods".[34]

In literary sources, the spread of Cybele's cult is presented as a source of conflict and crisis. Herodotus says that when Anacharsis returned to Scythia after traveling and acquiring knowledge among the Greeks in the 6th century BC, his brother, the Scythian king, put him to death for celebrating Cybele's mysteries.[35] The historicity of this account and that of Anacharsis himself are widely questioned.[36] In Athenian tradition, the city's Metroon was founded to placate Cybele, who had visited a plague on Athens when one of her wandering priests was killed for his attempt to introduce her cult. The earliest source is the Hymn to the Mother of the Gods (362 AD) by the Roman emperor Julian, but references to it appear in scholia from an earlier date. The account may reflect real resistance to Cybele's cult, but Lynne Roller sees it as a story intended to demonstrate Cybele's power, similar to myth of Dionysus' arrival in Thebes recounted in The Bacchae.[37][38][39] Many of Cybele's cults were funded privately, rather than by the polis,[26][40] but she also had publicly established temples in many Greek cities, including Athens and Olympia.[41] Her "vivid and forceful character" and association with the wild, set her apart from the Olympian deities.[42] Her association with Phrygia led to particular unease in Greece after the Persian Wars, as Phrygian symbols and costumes were increasingly associated with the Achaemenid Empire.[43]

Conflation with Rhea led to Cybele's association with various male demigods who served Rhea as attendants, or as guardians of her son, the infant Zeus, as he lay in the cave of his birth. In cult terms, they seem to have functioned as intercessors or intermediaries between goddess and mortal devotees, through dreams, waking trance, or ecstatic dance and song. They include the armed Curetes, who danced around Zeus and clashed their shields to amuse him; their supposedly Phrygian equivalents, the youthful Corybantes, who provided similarly wild and martial music, dance and song; and the dactyls and Telchines, magicians associated with metalworking.[44]

Cybele and Attis

[edit]

Cybele's major mythographic narratives attach to her relationship with Attis, who is described by ancient Greek and Roman sources and cults as her youthful consort, and as a Phrygian deity. In Phrygia, "Attis" was not a deity, but both a commonplace and priestly name, found alike in casual graffiti, the dedications of personal monuments, as well as at several of Cybele's Phrygian shrines and monuments. His divinity may therefore have begun as a Greek invention based on what was known of Cybele's Phrygian cult.[45] His earliest certain image as deity appears on a 4th-century BC Greek stele from Piraeus, near Athens. It shows him as the Hellenised stereotype of a rustic, eastern barbarian; he sits at ease, sporting the Phrygian cap and shepherd's crook of his later Greek and Roman cults. Before him stands a Phrygian goddess (identified by the inscription as Agdistis) who carries a tympanon in her left hand. With her right, she hands him a jug, as if to welcome him into her cult with a share of her own libation.[46] Later images of Attis show him as a shepherd, in similar relaxed attitudes, holding or playing the syrinx (panpipes).[47] In Demosthenes' On the Crown (330 BC), attes is "a ritual cry shouted by followers of mystic rites".[48]

Attis seems to have accompanied the diffusion of Cybele's cult through Magna Graecia; there is evidence of their joint cult at the Greek colonies of Marseille (Gaul) and Lokroi (southern Italy) from the 6th and 7th centuries BC. After Alexander the Great's conquests, "wandering devotees of the goddess became an increasingly common presence in Greek literature and social life; depictions of Attis have been found at numerous Greek sites".[38] When shown with Cybele, he is always the younger, lesser deity, or perhaps her priestly attendant. In the mid 2nd century, letters from the king of Pergamum to Cybele's shrine at Pessinos consistently address its chief priest as "Attis".[49][50]

Roman Cybele

[edit]Republican era

[edit]

Romans knew Cybele as Magna Mater ("Great Mother"), or as Magna Mater deorum Idaea ("great Idaean mother of the gods"), equivalent to the Greek title Meter Theon Idaia ("Mother of the Gods, from Mount Ida"). Rome officially adopted her cult during the Second Punic War (218 to 201 BC), after dire prodigies, including a meteor shower, a failed harvest, and famine, seemed to warn of Rome's imminent defeat. The Roman Senate and its religious advisers consulted the Sibylline oracle and decided that Carthage might be defeated if Rome imported the Magna Mater ("Great Mother") of Phrygian Pessinos.[52] As this cult object belonged to a Roman ally, the Kingdom of Pergamum, the Roman Senate sent ambassadors to seek the king's consent; en route, a consultation with the Greek oracle at Delphi confirmed that the goddess should be brought to Rome.[53] The goddess arrived in Rome in the form of Pessinos' black meteoric stone. Roman legend connects this voyage, or its end, to the matron Claudia Quinta, who was accused of unchastity but proved her innocence with a miraculous feat on behalf of the goddess. Publius Cornelius Scipio Nasica, supposedly the "best man" in Rome, was chosen to meet the goddess at Ostia; and Rome's most virtuous matrons (including Claudia Quinta) conducted her to the temple of Victoria, to await the completion of her temple on the Palatine Hill. Pessinos' stone was later used as the face of the statue of the goddess.[54] In due course, the famine ended and Hannibal was defeated.

Most modern scholarship agrees that Cybele's consort, Attis, and her eunuch Phrygian priests (Galli) would have arrived with the goddess, along with at least some of the wild, ecstatic features of her Greek and Phrygian cults. The histories of her arrival deal with the piety, purity, and status of the Romans involved, the success of their religious stratagem, and power of the goddess herself; she has no consort or priesthood, and seems fully Romanised from the first.[55] Some modern scholars assume that Attis must have followed much later; or that the Galli, described in later sources as shockingly effeminate and flamboyantly "un-Roman", must have been an unexpected consequence of bringing the goddess in blind obedience to the Sibyl; a case of "biting off more than one can chew".[56] Others note that Rome was well versed in the adoption (or sometimes, the "calling forth", or seizure) of foreign deities,[57] and the diplomats who negotiated Cybele's move to Rome would have been well-educated, and well-informed.[58]

Romans believed that Cybele, considered a Phrygian outsider even within her Greek cults, was the mother-goddess of ancient Troy (Ilium). Some of Rome's leading patrician families claimed Trojan ancestry; so the "return" of the Mother of all Gods to her once-exiled people would have been particularly welcome, even if her spouse and priesthood were not; its accomplishment would have reflected well on the principals involved and, in turn, on their descendants.[59] The upper classes who sponsored the Magna Mater's festivals delegated their organisation to the plebeian aediles, and honoured her and each other with lavish, private festival banquets from which her Galli would have been conspicuously absent.[60] Whereas in most of her Greek cults she dwelt outside the polis, in Rome she was the city's protector, contained within her Palatine precinct, along with her priesthood, at the geographical heart of Rome's most ancient religious traditions.[61] She was promoted as patrician property; a Roman matron – albeit a strange one, "with a stone for a face" – who acted for the clear benefit of the Roman state.[62][63]

Imperial era

[edit]Augustan ideology identified Magna Mater with Imperial order and Rome's religious authority throughout the empire. Augustus claimed a Trojan ancestry through his adoption by Julius Caesar and the divine favour of Venus; in the iconography of Imperial cult, the empress Livia was Magna Mater's earthly equivalent, Rome's protector and symbolic "Great Mother"; the goddess is portrayed with Livia's face on cameos[64] and statuary.[65] By this time, Rome had absorbed the goddess's Greek and Phrygian homelands, and the Roman version of Cybele as Imperial Rome's protector was introduced there.[66]

Imperial Magna Mater protected the empire's cities and agriculture — Ovid "stresses the barrenness of the earth before the Mother's arrival.[67] Virgil's Aeneid (written between 29 and 19 BC) embellishes her "Trojan" features; she is Berecyntian Cybele, mother of Jupiter himself, and protector of the Trojan prince Aeneas in his flight from the destruction of Troy. She gives the Trojans her sacred tree for shipbuilding, and begs Jupiter to make the ships indestructible. These ships become the means of escape for Aeneas and his men, guided toward Italy and a destiny as ancestors of the Roman people by Venus Genetrix. Once arrived in Italy, these ships have served their purpose and are transformed into sea nymphs.[68]

Stories of Magna Mater's arrival were used to promote the fame of its principals, and thus their descendants. Claudia Quinta's role as Rome's castissima femina (purest or most virtuous woman) became "increasingly glorified and fantastic"; she was shown in the costume of a Vestal Virgin, and Augustan ideology represented her as the ideal of virtuous Roman womanhood. The emperor Claudius claimed her among his ancestors.[69] Claudius promoted Attis to the Roman pantheon and placed his cult under the supervision of the quindecimviri (one of Rome's priestly colleges).[70]

Festivals and cults

[edit]Megalesia in April

[edit]

The Megalesia festival to Magna Mater commenced on April 4, the anniversary of her arrival in Rome. The festival structure is unclear, but it included ludi scaenici (plays and other entertainments based on religious themes), probably performed on the deeply stepped approach to her temple; some of the plays were commissioned from well-known playwrights. On April 10, her image was taken in public procession to the Circus Maximus, and chariot races were held there in her honour; a statue of Magna Mater was permanently sited on the racetrack's dividing barrier, showing the goddess seated on a lion's back.[72]

Roman bystanders seem to have perceived Megalesia as either characteristically "Greek";[73] or Phrygian. At the cusp of Rome's transition to Empire, the Greek Dionysius of Halicarnassus describes this procession as wild Phrygian "mummery" and "fabulous clap-trap", in contrast to the Megalesian sacrifices and games, carried out in what he admires as a dignified "traditional Roman" manner; Dionysius also applauds the wisdom of Roman religious law, which forbids the participation of any Roman citizen in the procession, and in the goddess's mysteries;[74] Slaves are forbidden to witness any of this.[75] In the late republican era, Lucretius vividly describes the procession's armed "war dancers" in their three-plumed helmets, clashing their shields together, bronze on bronze,[76] "delighted by blood"; yellow-robed, long-haired, perfumed Galli waving their knives, wild music of thrumming tympanons and shrill flutes. Along the route, rose petals are scattered, and clouds of incense arise.[77] The goddess's sculpted image wears the Mural Crown and is seated within a sculpted, lion-drawn chariot, carried high on a bier.[78] The Roman display of Cybele's Megalesia procession as an exotic, privileged public pageant offers signal contrast to what is known of the private, socially inclusive Phrygian-Greek mysteries on which it was based.[79]

'Holy week' in March

[edit]The Principate brought the development of an extended festival or "holy week"[80] for Cybele and Attis in March (Latin Martius), from the Ides to nearly the end of the month. Citizens and freedmen were allowed limited forms of participation in rites pertaining to Attis, through their membership of two colleges, each dedicated to a specific task; the Cannophores ("reed bearers") and the Dendrophores ("tree bearers").[81]

- March 15 (Ides): Canna intrat ("The Reed enters"), marking the birth of Attis and his exposure in the reeds along the Phrygian river Sangarius,[82] where he was discovered—depending on the version—by either shepherds or Cybele herself.[83] The reed was gathered and carried by the cannophores.[84]

- March 22: Arbor intrat ("The Tree enters"), commemorating the death of Attis under a pine tree. The dendrophores ("tree bearers") cut down a tree,[85] suspended from it an image of Attis,[86] and carried it to the temple with lamentations. The day was formalized as part of the official Roman calendar under Claudius.[87] A three-day period of mourning followed.[88]

Cybele and Attis (seated right, with Phrygian cap and shepherd's crook) in a chariot drawn by four lions, surrounded by dancing Corybantes (detail from the Parabiago plate; embossed silver, c. 200–400 AD, found in Milan, now at the Archaeological Museum of Milan) - March 23: on the Tubilustrium, an archaic holiday to Mars, the tree was laid to rest at the temple of the Magna Mater, with the traditional beating of the shields by Mars' priests the Salii and the lustration of the trumpets perhaps assimilated to the noisy music of the Corybantes.[89]

- March 24: Sanguem or Dies Sanguinis ("Day of Blood"), a frenzy of mourning when the devotees whipped themselves to sprinkle the altars and effigy of Attis with their own blood; some performed the self-castrations of the Galli. The "sacred night" followed, with Attis placed in his ritual tomb.[90]

- March 25 (vernal equinox on the Roman calendar): Hilaria ("Rejoicing"), when Attis was reborn.[91] Some early Christian sources associate this day with the resurrection of Jesus.[92] Damascius attributed a "liberation from Hades" to the Hilaria.[93]

- March 26: Requietio ("Day of Rest").[94]

- March 27: Lavatio ("Washing"), noted by Ovid and probably an innovation under Augustus,[95] Literary references indicate that the lavatio was "well established" by the Flavian period; [96] when Cybele's sacred stone was taken in procession from the Palatine temple to the Porta Capena and down the Appian Way to the stream called Almo, a tributary of the Tiber. There the stone and sacred iron implements were bathed "in the Phrygian manner" by a red-robed priest. The quindecimviri attended. The return trip was made by torchlight, with much rejoicing. The ceremony alluded to, but did not reenact, Cybele's original reception in the city, and seems not to have involved Attis.[95]

- March 28: Initium Caiani, sometimes interpreted as initiations into the mysteries of the Magna Mater and Attis at the Gaianum, near the Phrygianum sanctuary at the Vatican Hill.[97]

Scholars are divided as to whether the entire series was more or less put into place under Claudius,[98] or whether the festival grew over time.[99] The Phrygian character of the cult would have appealed to the Julio-Claudians as an expression of their claim to Trojan ancestry.[100] It may be that Claudius established observances mourning the death of Attis, before he had acquired his full significance as a resurrected god of rebirth, expressed by rejoicing at the later Canna intrat and by the Hilaria.[101] The full sequence at any rate is thought to have been official in the time of Antoninus Pius (reigned 138–161), but among extant fasti appears only in the Calendar of Philocalus (354 AD).[102][95]

Minor cults

[edit]Significant anniversaries, stations, and participants in the 204 arrival of the goddess – including her ship, which would have been thought a sacred object – may have been marked from the beginning by minor, local, or private rites and festivals at Ostia, Rome, and Victoria's temple. Cults to Claudia Quinta are likely, particularly in the Imperial era.[103] Rome seems to have introduced evergreen cones (pine or fir) to Cybele's iconography, based at least partly on Rome's "Trojan ancestor" myth, in which the goddess gave Aeneas her sacred tree for shipbuilding. The evergreen cones probably symbolised Attis' death and rebirth.[104][105] Despite the archaeological evidence of early cult to Attis at Cybele's Palatine precinct, no surviving Roman literary or epigraphic source mentions him until Catullus, whose poem 63 places him squarely within Magna Mater's mythology, as the hapless leader and prototype of her Galli.[106]

Taurobolium and Criobolium

[edit]

Rome's strictures against castration and citizen participation in Magna Mater's cult limited both the number and kind of her initiates. From the 160s AD, citizens who sought initiation to her mysteries could offer either of two forms of bloody animal sacrifice – and sometimes both – as lawful substitutes for self-castration. The Taurobolium sacrificed a bull, the most potent and costly victim in Roman religion; the Criobolium used a lesser victim, usually a ram.[109][110]

A late, melodramatic and antagonistic account by the Christian apologist Prudentius has a priest stand in a pit beneath a slatted wooden floor; his assistants or junior priests dispatch a bull, using a sacred spear. The priest emerges from the pit, drenched with the bull's blood, to the applause of the gathered spectators. This description of a Taurobolium as blood-bath is, if accurate, an exception to usual Roman sacrificial practice;[111] it may have been no more than a bull sacrifice in which the blood was carefully collected and offered to the deity, along with its organs of generation, the testicles.[112]

The Taurobolium and Criobolium are not tied to any particular date or festival, but probably draw on the same theological principles as the life, death, and rebirth cycle of the March "holy week". The celebrant personally and symbolically took the place of Attis, and like him was cleansed, renewed or, in emerging from the pit or tomb, "reborn".[113] These regenerative effects were thought to fade over time, but they could be renewed by further sacrifice. Some dedications transfer the regenerative power of the sacrifice to non-participants, including emperors, the Imperial family and the Roman state; some mark a dies natalis (birthday or anniversary) for the participant or recipient. Dedicants and participants could be male or female.[114]

The sheer expense of the Taurobolium ensured that its initiates were from Rome's highest class, and even the lesser offering of a Criobolium would have been beyond the means of the poor. Among the Roman masses, there is evidence of private devotion to Attis, but virtually none for initiations to Magna Mater's cult.[115]

In the religious revivalism of the later Imperial era, Magna Mater's notable initiates included the deeply religious, wealthy, and erudite praetorian prefect Praetextatus; the quindecimvir Volusianus, who was twice consul; and possibly the Emperor Julian.[116] Taurobolium dedications to Magna Mater tend to be more common in the Empire's western provinces than elsewhere, attested by inscriptions in (among others) Rome and Ostia in Italy, Lugdunum in Gaul, and Carthage in Africa.[117]

Priesthoods

[edit]"Attis" may have been a name or title of Cybele's priests or priest-kings in ancient Phrygia.[118] Most myths of the deified Attis present him as founder of Cybele's Galli priesthood but in Servius' account, written during the Roman Imperial era, Attis castrates a king to escape his unwanted sexual attentions, and is castrated in turn by the dying king. Cybele's priests find Attis at the base of a pine tree; he dies and they bury him, emasculate themselves in his memory, and celebrate him in their rites to the goddess. This account might attempt to explain the nature, origin, and structure of Pessinus' theocracy.[119] A Hellenistic poet refers to Cybele's priests in the feminine, as Gallai.[120] The Roman poet Catullus refers to Attis in the masculine until his emasculation, and in the feminine thereafter.[121] Various Roman sources refer to the Galli as a middle or third gender (medium genus or tertium sexus).[122] The Galli's voluntary emasculation in service of the goddess was thought to give them powers of prophecy.[123]

Pessinus, site of the temple whence the Magna Mater was brought to Rome, was a theocracy whose leading Galli may have been appointed via some form of adoption, to ensure "dynastic" succession. The highest ranking Gallus was known as "Attis", and his junior as "Battakes".[124] The Galli of Pessinus were politically influential; in 189 BC, they predicted or prayed for Roman victory in Rome's imminent war against the Galatians. The following year, perhaps in response to this gesture of goodwill, the Roman senate formally recognised Illium as the ancestral home of the Roman people, granting it extra territory and tax immunity.[125] In 103, a Battakes traveled to Rome and addressed its senate, either for the redress of impieties committed at his shrine, or to predict yet another Roman military success. He would have cut a remarkable figure, with "colourful attire and headdress, like a crown, with regal associations unwelcome to the Romans". Yet the senate supported him; and when a plebeian tribune who had violently opposed his right to address the senate died of a fever (or, in the alternative scenario, when the prophesied Roman victory came) Magna Mater's power seemed proven.[126]

In Rome, the Galli and their cult fell under the supreme authority of the pontifices, who were usually drawn from Rome's highest ranking, wealthiest citizens.[127] The Galli themselves, although imported to serve the day-to-day workings of their goddess's cult on Rome's behalf, represented an inversion of Roman priestly traditions in which senior priests were citizens, expected to raise families, and personally responsible for the running costs of their temples, assistants, cults, and festivals. As eunuchs, incapable of reproduction, the Galli were forbidden Roman citizenship and rights of inheritance; like their eastern counterparts, they were technically mendicants whose living depended on the pious generosity of others. For a few days of the year, during the Megalesia, Cybele's laws allowed them to leave their quarters, located within the goddess' temple complex, and roam the streets to beg for money. They were outsiders, marked out as Galli by their regalia, and their notoriously effeminate dress and demeanour, but as priests of a state cult, they were sacred and inviolate. From the start, they were objects of Roman fascination, scorn, and religious awe.[128] No Roman, not even a slave, could castrate himself "in honour of the Goddess" without penalty; in 101 BC, a slave who had done so was exiled.[129] Augustus selected priests from among his own freedmen to supervise Magna Mater's cult, and brought it under Imperial control.[130] Claudius introduced the senior priestly office of Archigallus, who was not a eunuch and held full Roman citizenship.[131]

The religiously lawful circumstances for a Gallus's self-castration remain unclear; some may have performed the operation on the Dies Sanguinis ("Day of Blood") in Cybele and Attis' March festival. Pliny describes the procedure as relatively safe, but it is not known at what stage in their career the Galli performed it, or exactly what was removed,[132] or even whether all Galli performed it. Some Galli devoted themselves to their goddess for most of their lives, maintained relationships with relatives and partners throughout, and eventually retired from service.[133] Galli remained a presence in Roman cities well into the Empire's Christian era. Some decades after Christianity became the sole Imperial religion, St. Augustine saw Galli "parading through the squares and streets of Carthage, with oiled hair and powdered faces, languid limbs and feminine gait, demanding even from the tradespeople the means of continuing to live in disgrace".[134]

Temples

[edit]

Greece

[edit]The earliest known temple for Cybele in the Greek world is the Daskalopetra monument on Chios, which dates to the sixth or early fifth centuries BC.[135] A Sanctuary of Cybele is also to be found in the city of Mytilene, Lesbos. The original structure dates back at least to the seventh century BC, with structural additions up until the fifth to sixth century AD.[136] In Greek, a temple to Cybele was often called a Metroon. Several Metroa were established in Greek cities from the fifth century BC onward. The Metroon at Athens was established in the early fifth century BC on the west side of the Athenian Agora, next to the Boule (town council). It was a rectangular building with three rooms and an altar in front. It was destroyed during the Persian sack of Athens in 480 BC, but repaired around 460 BC. The cult was deeply integrated into civic life; the Metroon was used as the state archive and Cybele was one of the four main deities, to whom serving councillors sacrificed, along with Zeus, Athena, and Apollo. The highly influential fifth-century BC statue of Cybele enthroned by Agoracritus was located in this building. The building was rebuilt around 150 BC, with separate rooms for cult worship and archival storage, and it remained in use until Late Antiquity.[137] A second Metroon in the Athenian suburb of Agrae was associated with the Eleusinian Mysteries.[138] At the end of the fifth century BC, a Metroon was established at Olympia. It is a small hexastyle temple, the third to be built on the site after the archaic Heraion and the mid-fifth century Temple of Zeus. In the Roman period it was used for the Imperial cult.[139] In the fourth century, further Metroa are attested at Smyrna and Colophon, where they also served as state archives, as in Athens.[140]

Rome and its provinces

[edit]Magna Mater's temple stood high on the slope of the Palatine, overlooking the valley of the Circus Maximus and facing the temple of Ceres on the slopes of the Aventine. It was accessible via a long upward flight of steps from a flattened area or proscenium below, where the goddess's festival games and plays were staged. At the top of the steps was a statue of the enthroned goddess, wearing a mural crown and attended by lions. Her altar stood at the base of the steps, at the proscenium's edge. The first temple was damaged by fire in 111 BC, and was repaired or rebuilt. It burnt down in the early Imperial era, and was restored by Augustus; it burned down again soon after, and Augustus rebuilt it in more sumptuous style; the Ara Pietatis relief shows its pediment.[141] The goddess is represented by her empty throne and crown, flanked by two figures of Attis reclining on tympanons; and by two lions who eat from bowls, as if tamed by her unseen presence. The scene probably represents a sellisternium, a form of banquet usually reserved for goddesses, in accordance with "Greek rite" as practiced in Rome.[142] This feast was probably held within the building, with attendance reserved for the aristocratic sponsors of the goddesses rites; the flesh of her sacrificial animal provided their meat.

From at least 139 AD, Rome's port at Ostia, the site of the goddess's arrival, had a fully developed sanctuary to Magna Mater and Attis, served by a local Archigallus and college of dendrophores (the ritual tree-bearers of "Holy Week").[143]

Ground preparations for the building of St. Peter's basilica on the Vatican Hill uncovered a shrine, known as the Phrygianum, with some 24 dedications to Magna Mater and Attis.[144] Many are now lost, but most that survive were dedicated by high-status Romans after a taurobolium sacrifice to Magna Mater. None of these dedicants were priests of the Magna Mater or Attis, and several held priesthoods of one or more different cults.[145]

Near Setif (Mauretania), the dendrophores and the faithful (religiosi) restored their temple of Cybele and Attis after a disastrous fire in 288 AD. Lavish new fittings paid for by the private group included the silver statue of Cybele and her processional chariot; the latter received a new canopy with tassels in the form of fir cones.[146] Cybele drew ire from Christians throughout the Empire; when St. Theodore of Amasea was granted time to recant his beliefs, he spent it by burning a temple of Cybele instead.[147]

Myths, theology, and cosmology

[edit]

Rome characterised the Phrygians as barbaric, effeminate orientals, prone to excess. While some Roman sources explained Attis' death as punishment for his excess devotion to Magna Mater, others saw it as punishment for his lack of devotion, or outright disloyalty.[148] Only one account of Attis and Cybele (related by Pausanias) omits any suggestion of a personal or sexual relationship between them; Attis achieves divinity through his support of Meter's cult, is killed by a boar sent by Zeus, who is envious of the cult's success, and is rewarded for his commitment with godhood.[149]

The most complex, vividly detailed, and lurid accounts of Magna Mater and Attis were produced as anti-pagan polemic in the late 4th century by the Christian apologist Arnobius, who presented their cults as a repulsive combination of blood-bath, incest, and sexual orgy, derived from the myths of Agdistis.[149] This has been presumed the most ancient, violent, and authentically Phrygian version of myth and cult, closely following an otherwise lost orthodox, approved version preserved by the priest-kings at Pessinous and imported to Rome. Arnobius claimed several scholarly sources as his authority; but the oldest versions are also the most fragmentary and, during an interval of several centuries, apt to diverge into whatever version suited a new audience, or potentially, new acolytes.[149] Greek versions of the myth recall those concerning the mortal Adonis and his divine lovers, - Aphrodite, who had some claim to cult as a 'Mother of all", or her rival for Adonis' love, Persephone - showing the grief and anger of a powerful goddess, mourning the helpless loss of her mortal beloved.[150]

The emotionally charged literary version presented in Catullus 63 follows Attis' initially ecstatic self-castration into exhausted sleep, and a waking realisation of all he has lost through his emotional slavery to a domineering and utterly self-centered goddess; it is narrated with a rising sense of isolation, oppression, and despair, virtually an inversion of the liberation promised by Cybele's Anatolian cult.[151] Contemporaneous with this, more or less, Dionysius of Halicarnassos pursues the idea that the "Phrygian degeneracy" of the Galli, personified in Attis, be removed from the Megalensia to reveal the dignified, "truly Roman" festival rites of the Magna Mater. Somewhat later, Vergil expresses the same deep tension and ambivalence regarding Rome's claimed Phrygian, Trojan ancestors, when he describes his hero Aeneas as a perfumed, effeminate Gallus, a half-man who would, however, "rid himself of the effeminacy of the Oriental in order to fulfill his destiny as the ancestor of Rome." This would entail him and his followers shedding their Phrygian language and culture, to follow the virile example of the Latins.[152] In Lucretius' description of the goddess and her acolytes in Rome, her priests provide an object lesson in the self-destruction wrought when passion and devotion exceed rational bounds; a warning, rather than an offer.[150]

For Lucretius, Roman Magna Mater "symbolised the world order": her image held reverentially aloft in procession signifies the Earth, which "hangs in the air". She is the mother of all, ultimately the Mother of humankind, and the yoked lions that draw her chariot show an otherwise ferocious offspring's duty of obedience to the parent.[153] She herself is uncreated, and thus essentially separate from and independent of her creations.[154]

In the early Imperial era, the Roman poet Manilius inserts Cybele as the thirteenth deity of an otherwise symmetrical, classic Greco-Roman zodiac, in which each of twelve zodiacal houses (represented by particular constellations) is ruled by one of twelve deities, known in Greece as the Twelve Olympians and in Rome as the Di Consentes. Manilius has Cybele and Jupiter as co-rulers of Leo (the Lion), in astrological opposition to Juno, who rules Aquarius.[155] Modern scholarship remarks that as Cybele's Leo rises above the horizon, Taurus (the Bull) sets; the lion thus dominates the bull. Some of the possible Greek models for Cybele's Megalensia festival include representations of lions attacking and dominating bulls. The festival date coincided, more or less, with events of the Roman agricultural calendar (around April 12) when farmers were advised to dig their vineyards, break up the soil, sow millet, "and – curiously apposite, given the nature of the Mother's priests – castrate cattle and other animals."[156]

In popular culture

[edit]

The Paseo del Prado axis in Madrid has as one of its extremes the Plaza de Cibeles ("Cybele's Square") with the Fountain of Cybele at its center. Fans of Real Madrid CF and the Spanish football national team celebrate their triumphs around the fountain, thus establishing the goddess as a symbol of Madrid and the Real Madrid football club.[157]

See also

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ "Cybele". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). HarperCollins. Retrieved December 15, 2019.

- ^ a b c R. S. P. Beekes, Etymological Dictionary of Greek, Brill, 2009, p. 794 (s.v. "Κυβέλη").

- ^ Jarus, Owen, 2,600-year-old inscription in Turkey finally deciphered — and it mentions goddess known 'simply as the Mother', Live Science, November 18, 2024

- ^ Roller 1999, pp. 228–232.

- ^ With reference to Cybele's origins and precursors, S.A. Takács describes "A terracotta statuette of a seated (mother) goddess giving birth with each hand on the head of a leopard or panther," Cybele, Attis and related cults: essays in memory of M.J. Vermaseren 1996:376; of this iconic type Walter Burkert says "The iconography found leads directly to the image of Kybele sitting upon her throne between two lions" (Burkert, Homo Necans (1983:79)).

- ^ Elizabeth Simpson, "Phrygian Furniture from Gordion", in Georgina Herrmann (ed.), The Furniture of Ancient Western Asia, Mainz 1996, pp. 198–201.

- ^ Roller 1999, pp. 67–68. This displaces the root meaning of "Cybele" as "she of the hair": see C.H.E. Haspels, The Highlands of Phrygia, 1971, I 293 no 13, noted in Burkert 1985 notes 17 and 18.

- ^ Motz 1997, p. 115.

- ^ Johnstone, in Lane 1996, p. 109.

- ^ Roller 1999, p. 53.

- ^ Kubaba was a queen of Kish's Third dynasty. She was worshipped at Carchemish, and her name was Hellenized as Kybebe. Motz 1997, pp. 105–106 takes this as the likely source of kubilya (cf. Roller 1999, pp. 67–68, where kubileya = mountain).

- ^ Pausanias, Description of Greece: "the Magnesians, who live to the north of Spil Mount, have on the rock Coddinus the most ancient of all the images of the Mother of the gods. The Magnesians say that it was made by Broteas the son of Tantalus." The image was probably Hittite in origin; see Roller 1999, p. 200.

- ^ Summers, in Lane 1996, p. 364.

- ^ Schmitz, Leonard, in Smith, William, Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, 1867, p. 67. link to perseus.org.

- ^ Roller 1994, pp. 248–56, suggests "Agdistis" as Cybele's personal name at Pessinos.

- ^ Roller 1999, pp. 110–114.

- ^ Roller 1999, pp. 69–71.

- ^ Takacs, in Lane 1996, p. 376

- ^ Roller 1999, pp. 111, 114, 140; for quotation, see p. 146.

- ^ Vecihi Özkay, "The Shaft Monuments and the 'Taurobolium' among the Phrygians", Anatolian Studies, Vol. 47, (1997), pp. 89–103, British Institute at Ankara.

- ^ Roller 1999, p. 125, citing Pindar, fragment 80 (Snell), Despoina Kubéla Mātēr ([δέσπ]οιν[αν] Κυβέ[λαν] ματ[έρα]).

- ^ Roller 1999, pp. 144–145, 170–176.

- ^ Potnia Therōn (Πότνια Θηρῶν) can sometimes be found as a title in ancient sources, but is used in modern scholarship for an iconographic schema, in which a female figure is flanked by or grips two animals.

- ^ Roller 1999, p. 135.

- ^ Roller 1999, p. 122.

- ^ a b Burkert 1985, p. 177

- ^ Roller 1994, p. 249.

- ^ Roller 1999, pp. 145–149.

- ^ Roller 1999, p. 157.

- ^ Strabo, Geography, book X, 3:18

- ^ Roller 1994, p. 253.

- ^ Roller 1999, pp. 143.

- ^ Roller 1999, pp. 225–227.

- ^ Roller 1999, pp. 149–151 and footnotes 20 – 25, citing Homeric Hymn 14, Pindar, Dithyramb II.10 (Snell), Euripides, Helen, 1347; Palamedes (Strabo 10.3.13); Bacchae, 64 – 169, Strabo 10.3.15 – 17 et al.

- ^ Johnstone, P.A., in Lane 1996, citing Herodotus, Histories, 4.76-7.

- ^ Roller 1999, pp. 156–157.

- ^ Roller 1999, pp. 162–167.

- ^ a b Roscoe 1996, p. 200.

- ^ Robertson, in Lane 1996, p. 258.

- ^ Roller 1999, pp. 140–144.

- ^ Roller 1999, pp. 161–163.

- ^ Roller, L., in Lane 1996, p. 306. See also Roller 1999, pp. 129, 139.

- ^ Roller 1999, pp. 168–169.

- ^ Roller 1999, pp. 171–172 (and notes 110 – 115), 173.

- ^ Roller believes that the name "Attis" was originally associated with the Phrygian Royal family and inherited by a Phrygian priesthood or theocracy devoted to the Mother Goddess, consistent with Attis' mythology as deified servant or priest of his goddess. Greek cults and Greek art associate this "Phrygian" costume with several non-Greek, "oriental" peoples, including their erstwhile foes, the Persians and Trojans. In some Greek states, Attis was met with outright hostility; but his vaguely "Trojan" associations would have been counted in his favour for the eventual promotion of his Roman cult. See Roller 1994, pp. 248–256. See also Roscoe 1996, pp. 198–199, and Johnstone, in Lane 1996, p. 106-107.

- ^ Both names are inscribed on the stele. Roller offers Agdistis as Phrygian Kybele's personal name. See Roller 1994, pp. 248–56. For discussion and critique on this and other complex narrative, cultic and mythological links among Cybele, Agdistis, and Attis, see Lancellotti, Maria Grazia, Brill, 2002 Attis, between myth and history: king, priest, and God, Archived 2016-04-29 at the Wayback Machine Brill, 2002.

- ^ The syrinx was a simple rustic instrument, associated with Pan, Greek god of shepherds, flocks, wild and wooded places, and unbridled sexuality. See Johnston, in Lane 1996, pp. 107–111, and Roller 1994, pp. 177–180. Pan is a "natural companion" for Cybele, and there is evidence of their joint cults.

- ^ Demosthenes, On the Crown, 260: cf the cry iache, invoking the god Iacchus in Demeter's Eleusinian Mysteries; Roller 1999, p. 181

- ^ Roller 1999, pp. 113–114.

- ^ Roller 1994, p. 254.

- ^ CIL 12.5374.

- ^ Beard 1994, p. 168, following Livy 29, 10 – 14 for Pessinos (ancient Galatia) as the shrine from which she was brought. Varro's Lingua Latina, 6.15 has Pergamum. Ovid Fasti 4.180–372 has it brought directly from Mt. Ida. For discussion of problems attendant on such precise claims of origin, see Tacaks, in Lane 1996, pp. 370–373.

- ^ Boatwright et al., The Romans, from Village to Empire ISBN 978-0-19-511875-9

- ^ Summers, in Lane 1996, pp. 363–364: "a rather bizarre looking statue with a stone for a face", Prudentius describes the stone as small, and encased in silver.

- ^ Beard 1994, pp. 168, 178–9. See also Summers, in Lane 1996, pp. 357–359. Attis' many votive statuettes at Cybele's Roman temple are evidence of his early, possibly private Roman cult.

- ^ Beard 1994, p. 177, citing Vermaseren, M.J., Cybele and Attis: the myth and the cult, Thames and Hudson, 1977, p. 96.

- ^ Several major Greek deities were adopted by Rome at about this time, including the Greek gods Aesclepius and Apollo. A version of Demeter's Thesmophoria was incorporated within the Roman cults to Ceres at around the same; Greek priestesses were brought to run the cult "for the benefit of the Roman state".

- ^ Takacs, in Lane 1996, p. 373, remarks that to presume Roman ignorance of the cult's true nature "makes Roman nobles look like buffoons, which they hardly were".

- ^ Roller 1999, p. 282.

- ^ Summers, in Lane 1996, pp. 337–339.

- ^ In Roman tradition, the she-wolf who found Romulus and Remus sheltered them in her lair on the Palatine, the Lupercal. See also Roller 1999, p. 273

- ^ Roller 1999, pp. 282–285. For statue description, see Summers, in Lane 1996, pp. 363–364.

- ^ cf the Roman response in 186 BC to the popular, unofficial, ecstatic Bacchanalia cults (originating as festivals to Dionysus, similar in form to Cybele's Greek cults), suppressed with great ferocity by the Roman state, very soon after the official introduction of Cybele's cult.

- ^ P. Lambrechts, "Livie-Cybele," La Nouvelle Clio 4 (1952): 251–60.

- ^ C. C. Vermeule, "Greek and Roman Portraits in North American Collections Open to the Public," Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 108 (1964): 106, 126, fig. 18.

- ^ In Greece and Phrygia, most cults to the goddess were popular, and privately funded; her former, ancient role as goddess of the former Phrygian State was as defunct as the state itself. See Roller 1999, p. 317.

- ^ Roller 1999, p. 280, citing Ovid, Fasti, 4. 299; cf "Phrygian Mater and Greek Meter, for whom fertility was rarely an issue, and whose association with wild and unstructured mountain landscape was directly at odds with agriculture and the settled countryside".

- ^ Virgil, Aeneid, Book IX, lines 79 - 83

- ^ Roller 1999, pp. 282, 314.

- ^ Roller 1999, pp. 315–316.

- ^ Michele Renee Salzman, On Roman Time: The Codex Calendar of 354 and the Rhythms of Urban Life in Late Antiquity (University of California Press, 1990), pp. 83–91, rejecting the scholarly tradition that the image represents an old man in an unknown rite for Venus

- ^ It was probably copied from a Greek original; the same appears on the Pergamon Altar. See Roller 1999, p. 315.

- ^ In the late Republican era, Cicero describes the hymns and ritual characteristics of Megalensia as Greek. See Takacs, in Lane 1996, p. 373.

- ^ Dionysius_of_Halicarnassus, Roman Antiquities, trans. Cary, Loeb, 1935, 2, 19, 3 – 5. See also commentary in Roller 1999, p. 293 and note 39: "... one can see how a Phrygian [priest] in an elaborately embroidered robe might have clashed noticeably with the plain, largely monochromatic Roman tunic and toga"; cf Augustus's "efforts to stress the white toga as the proper dress for Romans."

- ^ Roller 1999, p. 296, citing Cicero, De Haruspicum Responsis, 13. 28.

- ^ Recalling the Kouretes and Corybantes of Cybele's Greek myths and cults.

- ^ See Robertson, N., in Lane 1996, pp. 292–293. See also Summers, K., in Lane 1996, pp. 341, 347–349.

- ^ Summers, in Lane 1996, pp. 348–350.

- ^ Roller 1999, p. 317.

- ^ Maria Grazia Lancellotti, Attis, Between Myth and History: King, Priest, and God (Brill, 2002), p. 81; Bertrand Lançon, Rome in Late Antiquity (Routledge, 2001), p. 91; Philippe Borgeaud, Mother of the Gods: From Cybele to the Virgin Mary, translated by Lysa Hochroth (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004), pp. 51, 90, 123, 164.

- ^ Duncan Fishwick, "The Cannophori and the March Festival of Magna Mater", Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association, Vol. 97, (1966), p. 195 [1] Archived 2016-12-02 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Tertullian, Adversus Iudaeos 8; Lactantius, De Mortibus Persecutorum 2.1; Gary Forsythe, Time in Roman Religion: One Thousand Years of Religious History (Routledge, 2012), p. 88; Lancellotti, Attis, Between Myth and History, p. 81.

- ^ Michele Renee Salzman, On Roman Time: The Codex Calendar of 354 and the Rhythms of Urban Life in Late Antiquity (University of California Press, 1990), p. 166.

- ^ Duncan Fishwick, "The Cannophori and the March Festival of Magna Mater", Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association, Vol. 97, (1966), p. 195.

- ^ Alvar 2008, pp. 288–289.

- ^ Firmicus Maternus, De errore profanarum religionum, 27.1; Rabun Taylor, "Roman Oscilla: An Assessment", RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics 48 (Autumn 2005), p. 97.

- ^ John Lydus, De Mensibus 4.59; Suetonius, Otho 8.3; Forsythe, Time in Roman Religion, p. 88.

- ^ Forsythe, Time in Roman Religion, p. 88.

- ^ Salzman, On Roman Time, pp. 166–167.

- ^ Salzman, On Roman Time, p. 167; Lancellotti, Attis, Between Myth and History, p. 82.

- ^ Macrobius, Saturnalia 1.21.10; Forsythe, Time in Roman Religion, p. 88.

- ^ Tertullian, Adversus Iudaeos 8; Lactantius, De Mortibus Persecutorum 2.1; Forsythe, Time in Roman Religion, p. 88; Salzman, On Roman Time, p. 168.

- ^ Damascius, Vita Isidori excerpta a Photio Bibl. (Cod. 242), edition of R. Henry (Paris, 1971), p. 131; Salzman, On Roman Time, p. 168.

- ^ Salzman, On Roman Time, p. 167.

- ^ a b c Alvar 2008, pp. 286–287

- ^ Forsythe, Time in Roman Religion, p. 89.

- ^ Salzman, On Roman Time, pp. 165, 167. Lawrence Richardson, A New Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992), p. 180, suggests that Initium Caiani might instead refer to the "entry of Gaius" (Caligula) into Rome on March 28, 37 AD, when he was acclaimed as princeps. The Gaianum was a track used by Caligula for chariot exercises. Salzman (p. 169) sees the Gaianum as a site alternative to the Phrygianum, access to which would have been obstructed in the 4th century by the construction of St. Peter's.

- ^ Forsythe, Time in Roman Religion, p. 88, noting Jérôme Carcopino as the chief proponent of this view.

- ^ Alvar 2008, p. 286.

- ^ Forsythe, Time in Roman Religion, pp. 89–92.

- ^ Duncan Fishwick, "The Cannophori and the March Festival of Magna Mater", Transactions of the American Philological Association 97 (1966), p. 202.

- ^ Forsythe, Time in Roman Religion, p. 88

- ^ Roller 1999, p. 314.

- ^ Roller 1999, p. 279.

- ^ Takacs, in Lane 1996, p. 373.

- ^ Summers, K., in Lane 1996, pp. 377 ff.; for Catullus, see Takacs, in Lane 1996, pp. 367 ff.. For online Latin text and English translation of Catullus's poem 63, see vroma.org Archived 2014-05-28 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Taurobolium Matris Deum Augustae: CIL 13.1756.

- ^ CIL 13.1752.

- ^ See Duthoy 1969, p. 1 ff. Possible Greek precursors for the taurobolium are attested around 150 BC in Asia Minor, including Pergamum, and at Ilium (the traditional site of ancient Troy), which some Romans assumed as their own and Cybele's "native" city. The form of taurobolium presented by later Roman sources probably developed over time, and was not unique to Magna Mater – one was given at Puteoli in 134 AD to honour Venus Caelestia (C.I.L. X.1596) – but anti-pagan polemic represents it as hers. Some scholarship defines the Criobolium as a rite of Attis; but some dedication slabs show the bull's garlanded head (Taurobolium) with a ram's (Criobolium), and no mention of Attis.

- ^ See also Vecihi Özkay, "The Shaft Monuments and the 'Taurobolium' among the Phrygians", Anatolian Studies, Vol. 47, (1997), pp. 89–103, British Institute at Ankara, for speculation that some Phrygian shaft monuments anticipate the Taurobolium pit.

- ^ Prudentius is the sole original source for this version of a Taurobolium. Beard, p. 172, referring to it; "[this is] quite contrary to the practice of traditional civic sacrifice in Rome, in which the blood was carefully collected and the officiant never sullied." Duthoy 1969, p. 1 ff., believes that in early versions of these sacrifices, the animal's blood may have simply have been collected in a vessel; and that this was elaborated into what Prudentius more-or-less accurately describes. Cameron 2010, p. 163, outright rejects Prudentius' testimony as anti-pagan hearsay, sheer fabrication, and polemical embroidery of an ordinary bull-sacrifice.

- ^ Cameron 2010, p. 163 cf., the self-castration of Attis and the Galli.

- ^ Duthoy 1969, p. 119.

- ^ Duthoy 1969, p. 61 ff., 107, 101-104, 115 Some Taurobolium and Criobolium markers show a repetition between several years and more than two decades after.

- ^ Fear, in Lane 1996, pp. 41, 45.

- ^ Duthoy 1969, p. 1.

- ^ Duthoy 1969, p. 1 ff. (listing the relevant inscriptions).

- ^ As it was of her priest at Pessinus in the 2nd century BC: see Roller 1999, pp. 178–181.

- ^ Lancellotti, Maria Grazia, Attis, between myth and history: king, priest, and God, Brill, 2002, p. 6, citing Servius, Commentary on Vergil's Aeneid, 9.115.

- ^ "Gallai of the mountain mother, raving thyrsus-lovers," Γάλλαι μητρὸς ὀρείης φιλόθυρσοι δρομάδες, tentatively attributed to Callimachus as fr. inc. auct. 761 Pfeiffer.

- ^ See Catullus 63: Latin text Archived 2012-11-06 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Roscoe 1996, p. 203.

- ^ The Christian apologist Firmicus Maternus describes them as unnatural monstrosities and prodigies, filled "with an unholy spirit so as to seemingly predict the future to idle men"; see Roscoe 1996, p. 196.

- ^ Lancellotti, Maria Grazia, Attis, between myth and history: king, priest, and God, Brill, 2002, pp 101 – 104. This priestly "dynasty" may have begun around the 3rd century BC.

- ^ Roller 1999, p. 206.

- ^ See Roller 1999, pp. 290–291, citing Diodorus's description of Battakes, and the latter's prediction of Roman victory in Plutarch, "Life of Marius," 17.

- ^ Beard, 1994, p. 173 ff.

- ^ Roller 1999, pp. 318–319.

- ^ Roller 1999, p. 292.

- ^ Roller 1999, p. 315, citing CILl 6.496.

- ^ Fear, in Lane 1996, p. 47.

- ^ Roscoe 1996, p. 203, citing Pliny the Elder, Natural History, 11.261; 35.165, and noting that "Procedures called "castration" in ancient times encompassed everything from vasectomy to complete removal of penis and testicles.

- ^ Roscoe 1996, p. 203, and note 34, citing as example, the thanksgiving dedication to the Mother Goddess by a Gallus from Cyzicus (in Anatolia), in gratitude for her intervention on behalf of the soldier Marcus Stlaticus, his partner "(oulppiou, a term also applied to a husband or wife)".

- ^ St. Augustine, Book 7, 26, in Augustine, (trans. R W Dyson), The city of God against the pagans, Books 1 – 13, Cambridge University Press, 1998, p.299.

- ^ Roller 1999, pp. 137–138.

- ^ "Sanctuary of Cybele in Mytilene | Ψηφιακή ενοποίηση των αρχ/κών χώρων της Λέσβου". Retrieved 2025-09-05.

- ^ Roller 1999, pp. 162–163, 216–217.

- ^ Roller 1999, p. 175.

- ^ Roller 1999, pp. 161–162.

- ^ Roller 1999, pp. 163.

- ^ Roller 1999, pp. 309–310.

- ^ The sellisternium and various other elements of ritus Graecus "proved Rome's profound religious and cultural rooting in the Greek world". See Scheid, John, in Rüpke, Jörg (Editor), A Companion to Roman Religion, Wiley-Blackwell, 2007, p.226.

- ^ Duncan Fishwick, "The Cannophori and the March Festival of Magna Mater," Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association, Vol. 97, (1966), p. 199.

- ^ Cameron 2010, p. 142.

- ^ Cameron 2010, pp. 144–149.

- ^ Robin Lane Fox, Pagans and Christians, p. 581.

- ^ "St. Theodore of Amasea". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Encyclopedia Press. 1914. Archived from the original on 2018-06-26. Retrieved 2007-07-16.

- ^ Roller 1999, pp. 256–257.

- ^ a b c Roller 1999, pp. 241–244

- ^ a b Roller 1999, pp. 244–255

- ^ Roller 1999, pp. 304–305.

- ^ Roller 1999, pp. 302–304.

- ^ Summers, in Lane 1996, p. 339-340, 342; Lucretius claims the authority of "the old Greek poets" but describes the Roman version of Cybele's procession; to most of his Roman readers, his interpretations would have seemed familiar ground.

- ^ Roller 1999, pp. 297–299, citing Lucretius, De Rerum Natura, 2,598 – 660.

- ^ Hannah, Robert, "Manilius, the Mother of the Gods and the "Megalensia": an Astrological Anomaly resolved ?" Latomus, T. 45, Fasc. 4 (OCTOBRE-DÉCEMBRE 1986), pp. 864–872, Societe d’Etudes Latines de Bruxelles [2], citing Manlius, Astronomica, (trans. GP Goold, London, 1977) 2. 439 – 437.

- ^ Hannah, p. 872, citing Varro, De Re Rustica, 1. 30; Columella, De Re Rustica, 11. 2. 32 – 35; Pliny the Elder, Historia Naturalis, 18. 246 – 249.

- ^ Ortiz García 2006, pp. 199–200.

References

[edit]- Alvar, Jaime (2008). Romanising Oriental Gods: Myth, Salvation and Ethics in the Cults of Cybele, Isis and Mithras. Religions in the Graeco-Roman World. Vol. 165. Translated by Gordon, Richard. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-13293-1.

- Beard, Mary (1994). "The Roman and the foreign: the cult of the "great mother" in imperial Rome". In Thomas, Nicholas; Humphrey, Caroline (eds.). Shamanism, history, and the state. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. pp. 164–190. ISBN 978-04-72-10512-0. OCLC 29522597.

- Burkert, Walter (1985). "III.3.4". Greek Religion. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-06-74-36281-9.

- Cameron, Alan (2010). The Last Pagans of Rome. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-01-99-74727-6.

- Duthoy, Robert (1969). The Taurobolium: Its evolution and terminology. Études préliminaires aux religions orientales dans l'Empire romain. Vol. 10. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-00559-4.

- Lane, Eugene, ed. (1996). Cybele, Attis, and Related Cults: Essays in Memory of M.J. Vermaseren. Religions in the Graeco-Roman World. Vol. 131. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-10196-8.

- Motz, Lotte (1997). The Faces of the Goddess. US: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-01-95-08967-7.

- Ortiz García, Carmen (2006). "La Diosa Blanca y el Real Madrid. Celebraciones deportivas y espacio urbano". Disparidades. Revista de Antropología. 61 (2). Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas: 191–208. doi:10.3989/rdtp.2006.v61.i2.21. hdl:10261/7766. ISSN 0034-7981.

- Roller, Lynn Emrich (1994). "Attis on Greek Votive Monuments; Greek God or Phrygian?". Hesperia: The Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens. 63 (2): 245–262. JSTOR 148115 – via Studylib.

- Roller, Lynn Emrich (1999). In Search of God the Mother: The Cult of Anatolian Cybele. Berkeley and Los Angeles, California: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-21024-7.

- Roscoe, Will (1996). "Priests of the Goddess: Gender Transgression in Ancient Religion". History of Religions. 35 (3): 195–230. doi:10.1086/463425. S2CID 162368477..

Further reading

[edit]- Blank, Thomas (2024). Religiöse Geheimniskommunikation in der Mittleren und Späten Römischen Republik. Separatheit, gesellschaftliche Öffentlichkeit und zivisches Ordnungshandeln. Potsdamer Altertumswissenschaftliche Beiträge, vol. 82. Stuttgart: Steiner, ISBN 978-3-515-13386-9, on the Roman Magna Mater pp. 123–207.

- D’Andria, Francesco, Mahmut Bilge Baştürk, and James Hargrave (2019). "The Cult of Cybele in Hierapolis of Phrygia". In: Phrygia in Antiquity: From the Bronze Age to the Byzantine Period: Proceedings of an International Conference. Edited by Gocha R. Tsetskhladze. Peeters, pp. 479–500. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv1q26v1n.28.

- Knauer, Elfried R. (2006). "The Queen Mother of the West: A Study of the Influence of Western Prototypes on the Iconography of the Taoist Deity." In: Contact and Exchange in the Ancient World. Ed. Victor H. Mair. University of Hawai'i Press, ISBN 0-8248-2884-4. Pp. 62–115. (An article showing the probable derivation of the Daoist goddess, Xi Wangmu, from Kybele/Cybele)

- Laroche, Lotte (1960). Koubaba, déesse anatolienne, et le problème des origines de Cybèle. Eléments orientaux dans la religion grecque ancienne. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. pp. 113–128.

- Munn, Mark (2008). "Kybele as Kubaba in a Lydo-Phrygian Context". In: Anatolian Interfaces: Hittites, Greeks and Their Neighbours. Edited by Billie Jean Collins, Mary R.Bachvarova, and Ian C. Rutherford. Oxford: Oxbow. pp. 159-164. www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1cd0nsg.22.

- Roller, Lynne E. (1994). "The Phrygian Character of Kybele: The Formation of an Iconography and Cult Ethos in the Iron Age". In: Anatolian Iron Ages 3: The Proceedings of the Third Anatolian Iron Ages Colloquium Held at Van, 6-12 August 1990. Edited by A. Çilingiroğlu and D. H. French. London: British Institute at Ankara. pp. 189-98. www.jstor.org/stable/10.18866/j.ctt1pc5gxc.29.

- Vassileva, Maya (2001). "Further considerations on the cult of Kybele". Anatolian Studies. 51. British Institute at Ankara: 51–64. doi:10.2307/3643027. JSTOR 3643027. S2CID 162629321.

- Vermaseren, Maarten Jozef (1977). Cybele and Attis: The Myth and the Cult trans. from Dutch by A. M. H. Lemmers. Thames and Hudson.

- Virgil (2003). The Aeneid trans from Latin by David West. Penguin Putnam Inc.

External links

[edit]- Britannica Online Encyclopædia

- Showerman, Grant (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 12 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 401–403.

- Ancient History Sourcebook: Roman Religiones Licitae and Illicitae, c. 204 BC-112 AD Archived 2014-11-17 at the Wayback Machine

- The Warburg Institute Iconographic Database (images of Cybele)

Cybele

View on GrokipediaCybele, also known as Matar or Kubileya in Phrygian contexts, was the paramount mother goddess of ancient Anatolia, particularly revered in Phrygia as a deity of fertility, mountains, and natural sovereignty, with archaeological evidence tracing her cult to rock-cut shrines and inscriptions from the 8th century BCE onward.[1] Her worship featured ecstatic rituals, including music from tambourines and cymbals, processions with her sacred symbol—a black meteorite housed in a temple—and male priests called Galli who underwent ritual self-castration to emulate her consort Attis, a figure integrated later through Greek influence.[2][3] Adopted by Greek settlers in Asia Minor by the 6th century BCE, the cult spread westward, culminating in its state-sanctioned importation to Rome in 204 BCE as Magna Mater during the Second Punic War, prompted by a Sibylline oracle promising victory over Hannibal through her favor, after which a temple was dedicated on the Palatine Hill.[4][5] In Roman practice, her festivals like the Megalesia involved theatrical performances and bull sacrifices known as taurobolia, symbolizing renewal, though the more extreme Phrygian elements such as public self-mutilation were gradually curtailed to align with Roman sensibilities, reflecting a pragmatic adaptation of foreign rites to bolster imperial legitimacy and address perceived fertility crises.[6][7] Archaeological finds, including recent excavations of sanctuaries in western Phrygia, confirm the cult's deep indigenous roots predating Hellenic modifications, underscoring its evolution from local Anatolian earth worship to a syncretic Mediterranean phenomenon.[8]