Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Wayana

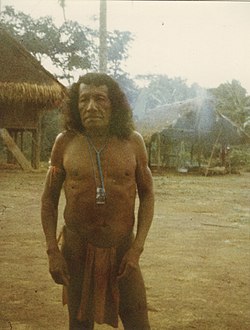

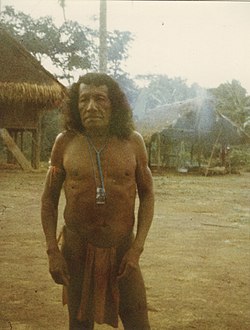

View on WikipediaThe Wayana (alternate names: Ajana, Uaiana, Alucuyana, Guaque, Ojana, Oyana, Orcocoyana, Pirixi, Urukuena, Waiano etc.) are a Carib-speaking people located in the southeastern part of the Guiana highlands, a region divided between Brazil, Suriname, and French Guiana. In 1980, when the last census took place, the Wayana numbered some 1,500 individuals, of which 150 in Brazil, among the Apalai, 400 in Suriname, and 1,000 in French Guiana, along the Maroni River. About half of them still speak their original language.

Key Information

History

[edit]According to both oral tradition and descriptions by 20th century European explorers, the Wayana emerged fairly recently as a distinctive group; contemporary Wayana are considered an amalgation of smaller ethnic groups such as the Upului, Opagwana, and Kukuyana.[2] In the eighteenth century, the ancestors of the Wayana lived along the Paru and Jari rivers in contemporary Brazil, and along the upper tributaries of the Oyapock river, which nowadays forms the border between French Guiana and Brazil.[3]

The first recorded mentioning of the tribe was in 1769 across a Wayana village.[4] By the late 18th century, the ancestors of the Wayana were involved in an almost continuous military struggle with Tupi peoples such as the Wayampi, which drove them across the Tumuk Humak Mountains to the upper tributaries of the Litani river.[5] Around the same time, the Aluku maroons, who had fled plantations in Suriname, were driven up the Litani river by Dutch colonial forces aided by Ndyuka maroons, who had settled for peace with the colonial authorities in return for military assistance against "incursions" from new maroon groups. From that moment on, an intensive trade relationship developed between the Wayana and the Aluku,[6] and both tribes often living together in the same villages.[7] In 1815, the Aluku and Wayana became blood brothers.[8]

Over time, the Wayana migrated with the Aluku further downstream the Litani and Lawa rivers to end up in their contemporary position. In 1865, the Ndyuka granman Alabi invited a Wayana group still living along the Paru river in Brazil to join them along the Tapanahony river in Suriname, probably inspired by the arrangement with the Wayana that the Aluku had. This particular group still lives in villages along the Tapanahony and Palumeu rivers.[6]

Despite limited contacts with outsiders, imported diseases ravished the tribe in the early 20th century, and reduced the population to an estimated 500 to 600 people.[9] From 1962 onward, American missionaries from the West-Indies Mission, who had previously worked with the Tiriyó, encouraged the population to concentrate in larger villages and provided access to health care, schooling, and to make it easier to convert the population.[10] The French part of the interior used to be the Territory of Inini[11] which allowed for an autonomous and self sufficient tribal system for the native population without clear borders.[12] In 1968 the Wayana settlements in France became part of the Grand-Santi-Papaïchton community circle of French Guiana which became separate communes a year later.[13] Along with the commune, came a government structure, and francisation.[12] In the late 1980s, the Surinamese Interior War stopped development on the Suriname side and many fled to the French side of the border.[14] The late 20th and early 21st century marked the beginning of (eco)tourism, but also illegal gold mining.[15] Along with miners came the bars, prostitution, and gambling. The Maripasoula commune is sometimes referred to as "Far West" in the mainstream French media, because of its high crime rate.[16][17]

Society and culture

[edit]Wayana society is characterized by a rather low degree of social stratification. Villages often comprise not more than one extended family and are rather loosely linked to their neighbouring villages by kinship ties, marital exchanges, shared rituals and trade. Missionaries and representatives of the state have only partially succeeded in grouping the Wayana together in larger settlements, and despite the fact that the Wayana are not as nomadic as before, villages are by no means permanent, and are often abandoned after the death of a leader.[18]

Villages are often led by a shaman or pïyai, who mediate Wayana contact with the world of spirits and deities, act as healers, and who are consulted in matters concerning hunting and fishing. Many Wayana villages still feature a community house or tukusipan.

Ëputop

[edit]Coming of age was for a long time associated with a ritual called ëputop or maraké, in which a wicker frame full of stinging ants or wasps was applied to the bodies of adolescent boys and girls, who emerged from the ceremony as adult men and women. While older Wayana still to a degree define their Wayanahood by the number of ëputop they underwent during their lifetime, many younger Wayana reject the necessity of undergoing ëputop to become a valued member of society. As a result, few ëputop ceremonies occur today.[19] One of the more recent ëputop ceremonies took place in 2004 in the village of Talhuwen, organized by Aïmawale Opoya, grandson of Wayana leader Janomalë, in consultation with French film director Jean-Philippe Isel, who made a documentary about the ritual.[20][21][22]

In spite of its demise, ëputop was listed on the inventory of intangible cultural heritage drawn up by the French Ministry of Culture in 2011.

Political organisation

[edit]| Granman of the Wayana | |

|---|---|

| Suriname | |

| Incumbent Aptuk Noewahe since 1976[23] | |

| Residence | Pïlëuwimë |

| French Guiana | |

| Incumbent Amaipotï since 1985[24] | |

| Residence | Kulumuli |

Before contact with missionaries and state representatives, the Wayana did not recognise a form of leadership that transcended the village level. The Surinamese, French, and Brazilian states preferred to centralise their dealings with the Wayana, however, and for this purpose installed captains, head captains and granman among the Wayana leaders. As the concept of a paramount chief goes against Wayana ideas of political organisation, the authority of these chiefs beyond their own villages is often limited.[25][26]

In Suriname, Kananoe Apetina was made "head captain" of the Wayana on the Tapanahony river in 1937, while Janomalë was made "head captain" of the Wayana on the Lawa and Litani rivers in 1938. After the death of Janomalë in 1958, Anapaikë was installed as his successor, and served as the leader of the Wayana on the Surinamese side of the Lawa river until he died in 2003.[27] Kananu Apetina died in 1975 and was succeeded by Aptuk Noewahe, who was recognised by the Surinamese government as the granman of all Wayana in Suriname until his death in 2023. The current head captain on the Lawa river is Ipomadi Pelenapïn, who was installed in August 2005.[26]

The current granman of the Wayana in French Guiana is Amaipotï, son of first granman Twenkë, who resides in the village of Kulumuli.[28]

Contemporary settlements

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Heemskerk et al. 2007, p. 74.

- ^ Boven 2006, p. 59.

- ^ Boven 2006, p. 63.

- ^ Boven 2006, p. 283.

- ^ Boven 2006, pp. 63, 67.

- ^ a b Boven 2006, p. 77.

- ^ Fleury 2018, p. 30.

- ^ Fleury 2018, p. 32.

- ^ Boven 2006, p. 44.

- ^ Boven 2006, p. 45.

- ^ "Création de territoire en Guyane françaises". Journal officiel de la Guyane française via Bibliothèque Nationale de France (in French). 18 June 1930. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- ^ a b "The Aluku and the Communes in French Guiana". Cultural Survival. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- ^ "Parcours La Source". Parc-Amazonien-Guyane (in French). Archived from the original on 31 December 2022. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- ^ Boven 2006, p. 46.

- ^ Boven 2006, p. 47.

- ^ "Pour l'or de Maripasoula". Le Monde.fr (in French). 6 July 2001. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

Far West is in the first paragraph which can be read without paying.

- ^ "Guyane : se soigner au coeur de l'Amazonie". Rose Up (in French). 2 December 2019.

- ^ "Wayana: social organisation". Povos Indígenas no Brazil. Retrieved 1 March 2018.

- ^ Boven 2006, pp. 147–156.

- ^ Boven 2006, p. 154.

- ^ "" Ëputop, un maraké wayana " Un film de Jean-Philippe Isel". Blada.com. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- ^ "Eputop, un maraké wayana". Télérama.fr. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- ^ Boven 2006, p. 108.

- ^ Chapuis 2007, p. 184.

- ^ "Wayana: political organisation". Povos Indígenas no Brazil. Retrieved 1 March 2018.

- ^ a b Boven 2006, p. 243.

- ^ Boven 2006, p. 168.

- ^ Fleury, Opoya & Aloïké 2016, p. 90.

- ^ a b c d e "Dorpen en Dorpsbesturen". Vereniging van Inheemse Dorpshoofden in Suriname (in Dutch). Archived from the original on 8 October 2021. Retrieved 4 February 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Duin 2009, p. 138.

- ^ a b c Duin 2009, p. 394.

- ^ Duin 2009, p. 239.

- ^ a b c Duin 2009, p. 139.

- ^ a b Heemskerk et al. 2007, p. 21.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Iori van Velthem Linke (2018). "Gestão territorial e ambiental nas terras indígenas do Rio Paru de Leste: um desafio coletivo no norte da Amazônia brasileira". University of Brasília (in Portuguese). p. 71. Retrieved 26 January 2022.

- ^ "Caracterização do DSEI Amapá e Norte do Pará, conforme Edital de Chamada Pública n. 2/2017 (item 3.1)" (PDF). portalarquivos.saude.gov.br. 30 June 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 May 2018. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

References

[edit]- Alì, Maurizio & Ailincai, Rodica. (2013). “Learning and Growing in indigenous Amazonia. The Education System of French Guyana Wayana-Apalai communities”. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences (Elsevier), 106 (10): 1742–1752. ISSN 1877-0428. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.12.196

- Boven, Karin M. (2006). Overleven in een Grensgebied: Veranderingsprocessen bij de Wayana in Suriname en Frans-Guyana (PDF). Amsterdam: Rozenberg Publishers.

- Chapuis, Jean (2007). L'ultime fleur. Ekulunpï tïhmelë. Essai d'ethnosociogenèse wayana (PDF) (Thesis) (in French). Orléans: Les Presses universitaires.

- Duin, Renzo Sebastiaan (2009). Wayana Socio-political Landscapes: Multi-scalar Regionality and Temporality in Guiana (PDF). University of Florida. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-07-13. Retrieved 2018-02-25.

- Fleury, Marie (2018). "Gaan Mawina, le Marouini (haut Maroni) au cœur de l'histoire des Noirs marrons Boni/Aluku et des Amérindiens Wayana". Revue d'Ethnoécologie. Revue d’ethnoécologie 13, 2018 (in French) (13). doi:10.4000/ethnoecologie.3534.

- Fleury, Marie; Opoya, Tasikale; Aloïké, Waiso (2016). "Les Wayana de Guyane française sur les traces de leur histoire" (PDF). Revue d'ethnoécologie. 9 (9). doi:10.4000/ethnoecologie.2711.

- Heemskerk, Marieke; Delvoye, Katia; Noordam, Dirk; Teunissen, Pieter (2007). Wayana Baseline Study: A sustainable livelihoods perspective on the Wayana Indigenous Peoples living in and around Puleowime (Apetina), Palumeu, and Kawemhakan (Anapaike) in Southeast Suriname (PDF). Paramaribo: Stichting Amazon Conservation Team-Suriname.

- Ricardo, Carlos Alberto, ed. (1983). Povos indígenas no Brasil vol. 3: Amapá / Norte do Pará (PDF). São Paulo: CEDI.

- Van Velthem, Lucia Hussak (1976). "Representações gráficas Wayãna-Aparaí" (PDF). Boletim do Museo Paraense Emílio Goeldi. 64: 1–19. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- Van Velthem, Lucia Hussak (1980). "O Parque Indígena de Tumucumaque" (PDF). Boletim do Museo Paraense Emílio Goeldi. 76: 1–31. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- Van Velthem, Lucia Hussak (1990). "Os Wayana, as águas, os peixes e a pesca" (PDF). Boletim do Museo Paraense Emílio Goeldi. Série Antropologia. 6 (1): 107–116. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- Van Velthem, Lucia Hussak (2009). "Mulheres de cera, argila e arumã: princípios criativos e fabricação material entre os Wayana". Mana. 15 (1): 213–236. doi:10.1590/S0104-93132009000100008.

- Van Velthem, Lucia Hussak (2010a). "Artes indígenas: notas sobre a lógica dos corpos e dos artefatos". Textos Escolhidos de Cultura e Arte Populares. 7 (1): 19–29. doi:10.12957/tecap.2010.12052.

- Van Velthem, Lucia Hussak (2010b). "Os "originais" e os "importados": referências sobre a apreensão wayana dos bens materiais". Indiana. 27: 141–159. doi:10.18441/ind.v27i0.141-159.

- Van Velthem, Lucia Hussak (2014). "Serpentes de Arumã. Fabricação e estética entre os Wayana (Wajana) na Amazônia Oriental". PROA: Revista de Antropologia e Arte. 5 (1). Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- Van Velthem, Lucia Hussak; Van Velthem Linke, Iori Leonel H. (2010). Livro da Arte Gráfica Wayana e Aparai: Waiana anon imelikut pampila – Aparai zonony imenuru papeh (PDF). Rio de Janeiro: Museu do Índio – FUNAI / IEPÉ. ISBN 978-85-85986-29-2.

- "Wayana". Ethnologue.com.

- Wilbert, Johannes; Levinson, David (1994). Encyclopedia of World Cultures. Volume 7: South America. Boston: G. K. Hall. ISBN 0-8161-1813-2

Further reading

[edit]- Devillers, Carole (January 1983). "What Future for the Wayanas?". National Geographic. Vol. 163, no. 1. pp. 66–83. ISSN 0027-9358. OCLC 643483454.

Wayana

View on GrokipediaHistory

Origins and pre-colonial period

The Wayana language belongs to the Cariban (Karib) family, whose proto-languages trace origins to the Orinoco River basin in present-day Venezuela, with expansions northward and eastward into the Guianas occurring during the first millennium CE and intensifying in the centuries before European contact.[8][9] Linguistic reconstructions indicate that Cariban speakers displaced or assimilated earlier Arawakan and other groups, establishing dominance in the interior Guiana Shield by associating with pottery styles and settlement patterns evidencing increased riverine occupation around 1000–1500 CE.[10] This migratory dynamic, rather than a singular mass movement, involved gradual diffusion of populations, technologies, and idioms, as archaeological data from sites in northern Amazonia show continuity in Cariban-linked material culture without abrupt ruptures.[11] Ancestral Wayana groups adapted autonomously to the Precambrian Guiana Shield's rugged terrain and tropical rainforests, forming small, flexible settlements along rivers such as the Paru d'Oeste, upper Jari, Litani, and Maroni, where floodplain soils supported slash-and-burn agriculture of bitter manioc, supplemented by hunting, fishing, and gathering.[1] These riverine locations facilitated mobility via dugout canoes and access to diverse ecosystems, with villages featuring elongated communal houses (tapyi) and ritual structures (tukusipan) built from local timbers and thatch, reflecting egalitarian social units organized around kinship and seasonal resource cycles.[1] Archaeological correlates in the region, including earthworks and ceramic scatters, underscore self-reliant economies resilient to environmental variability, with no evidence of large-scale hierarchies or external dependencies pre-contact.[10] Proto-Wayana identity coalesced through totemic clan systems, as preserved in oral cosmogonies invoking creator ancestors like Mopó and vital essences (uzenu), which structured alliances, exogamous marriages, and ritual exchanges with proximate Cariban peoples such as the Aparai. These interactions, inferred from ethnographic reconstructions and shared mythological motifs, involved both cooperative trading networks for feathers, tools, and salt, and sporadic conflicts over hunting grounds, fostering a fluid ethnic boundary via assimilated subgroups rather than rigid isolation.[1] Such relational dynamics, embedded in landscape-oriented narratives, enabled adaptive resilience in the pre-colonial era, prior to disruptions from Atlantic incursions.Colonial contacts and early impacts

The Wayana, inhabiting remote interior regions of the Guiana Shield, experienced initial European contacts primarily in the mid-to-late 18th century, mediated through French and Dutch colonial expansions in French Guiana and Suriname. Documented first encounters occurred during Wayana migrations northward from northeastern Brazil, driven by inter-indigenous conflicts exacerbated by Portuguese arming of Amazonian slavers; French botanist François Étienne Patris recorded meeting Wayana groups in 1767 while crossing the Tumuc-Humac mountains into French Guiana.[12] Dutch explorations in Suriname's southern interior, following the colony's establishment in 1667, likely involved indirect trade networks rather than direct settlement, as Wayana territories along upper tributaries like the Marowijne remained peripheral to coastal plantations.[13] These contacts introduced Old World diseases—such as smallpox and measles—via trade routes and displaced coastal indigenous groups, contributing to broader demographic collapses among Guianese Amerindians, though Wayana isolation mitigated immediate devastation compared to coastal populations.[12] Mid-18th-century slave-hunting raids by Portuguese-allied groups further pressured Wayana bands, prompting relocation to headwaters of rivers like the Marouini, Litani, and Mapaoni to evade capture, a strategy reflecting adaptive mobility over direct confrontation.[12] By century's end, conflicts with dominant Kali'na groups, intensified by colonial dynamics, reinforced this inland shift, prioritizing survival through dispersal rather than fixed settlements vulnerable to exploitation. Trade emerged as a key interaction vector, with Wayana exchanging forest products for iron tools and European goods via intermediaries like lower Oyapock River traders by the late 1700s, fostering selective integration without wholesale assimilation.[12] Avoidance of coastal European outposts and emerging maroon (bushinengue) communities in northern Guiana underscored pragmatic resistance, as Wayana groups leveraged geographic barriers and kinship networks to minimize exposure to enslavement and missionary incursions, which were limited in their southern domains during this era.[12] This pattern of strategic withdrawal preserved core cultural practices amid cascading colonial pressures.19th-20th century migrations and ethnogenesis

During the 19th century, Wayana groups, originally dispersed along rivers such as the upper East Paru and Jari in Brazil, experienced migrations northward into Suriname and French Guiana, fleeing intensified European contacts and conflicts that had begun in the 18th century.[3] In 1865, for instance, the Ndyuka granman Alabi invited a Wayana band from the Paru River in Brazil to settle along the Tapanahoni River in Suriname, contributing to early post-colonial regrouping amid emerging colonial borders.[14] These movements concentrated populations along the tri-national frontier, where subgroups like the Upului, Opagwana, and Kukuyana fused through shared survival strategies, laying groundwork for a consolidated Wayana identity via retained ritual elements such as Upului shamanic terminology.[3] The early 20th-century rubber boom (circa 1920–1940) in Brazilian basins like the Jari, East Paru, Maicuru, and Curuá drew many Wayana and affiliated Aparai into wage labor as tappers, exchanging food and services for manufactured goods, which disrupted traditional economies and prompted further displacements toward less exploited border areas in Suriname and French Guiana.[1] By the 1950s, Wayana settlements stabilized on middle and upper stretches of the East Paru, Jari, Litani, and Paloemeu rivers across the three countries, with ongoing influxes from Brazil due to resource extraction pressures.[1] Ethnogenesis accelerated in the 20th century through intermarriages and cultural exchanges with neighboring Carib-speaking groups, particularly Aparai—some of whom assimilated into Wayana communities—and Trio, despite historical hostilities involving raids for resources and brides.[3][1] These unions, favoring cross-cousin preferences within expanding kin networks, integrated Tupi loanwords and rituals, solidifying a pan-Wayana identity by the mid-1900s, distinct yet hybridized, as evidenced by the emergent "Wayana-Aparai" ethnonym in Brazilian records by the 1970s.[1] Oral histories emphasize shared ordeals from external incursions, fostering cohesion without erasing subgroup distinctions. Post-World War II migrations remained limited for Wayana, but Suriname's 1975 independence indirectly influenced interior dynamics through policy divergences, with some families shifting to French Guiana by the late 20th century for enhanced indigenous support in education and healthcare, reflecting pragmatic responses to varying national frameworks rather than mass displacements.[3] Ethnographic data indicate a total Wayana population of approximately 2,500 by this period, distributed as roughly 400 in Suriname, 150 in Brazil, and 200 in French Guiana, underscoring border-induced consolidation over fragmentation.[5][3]Language

Classification and features

The Wayana language belongs to the Cariban language family, specifically within the Guianan subgroup of the Northern Cariban branch, which encompasses languages spoken across the Guiana Shield in northern South America. This classification is supported by comparative lexical and morphological evidence linking Wayana to other Cariban varieties, such as Tiriyó and Apalaí, though it remains distinct with limited mutual intelligibility beyond close dialects. Approximately 1,000–1,500 speakers use Wayana across its range, with no evidence of it forming an isolate within the family.[15][9] Dialectal variation in Wayana correlates with geographic separation, including forms spoken along the Litany and Maroni rivers in French Guiana and Suriname, and the upper Paru and Jari rivers in Brazil, where phonetic and lexical differences emerge, such as in fricative realizations and minor vocabulary shifts influenced by local contact. These variants maintain core grammatical unity but exhibit substrate effects from neighboring languages like Teko (an Arawakan language) in French Guiana. Scholarly documentation, including field-based recordings from the 2000s, confirms continuity in basic lexicon from proto-Cariban roots, such as terms for kinship and environment, despite regional borrowings.[16] Phonologically, Wayana inventory includes 20–25 consonants, featuring voiced and voiceless fricatives (/f, s, ʃ/), approximants, and a glottal or uvular stop that distinguishes it from some sibling languages; vowels exhibit nasalization and length contrasts, with no productive tone system documented. Morphologically, it is agglutinative, relying on suffixation for derivation and inflection, including postpositional phrases and verb serialization typical of Cariban syntax. Nouns incorporate classifiers sensitive to animacy, assigning masculine or feminine gender to animates via dedicated affixes (e.g., -ne for masculine human), while inanimates lack such marking, reflecting a semantic hierarchy prioritizing agency and biological sex.[16][17]Vitality and endangerment

The Wayana language has an estimated 900 speakers, distributed as approximately 600 in Suriname, 200 in French Guiana, and 150 in Brazil, based on assessments from indigenous language surveys.[18] Ethnologue classifies its vitality as stable within remote communities, reflecting sustained use among adults in isolated villages along the upper Maroni and Tumuc-Humac rivers.[19] However, standardized metrics indicate vulnerability due to faltering intergenerational transmission, with younger speakers increasingly adopting Dutch in Suriname, French in French Guiana, and Portuguese in Brazil as primary languages for education and external interaction.[20] Transmission failures stem from small population sizes—totaling under 3,000 Wayana people—and frequent exogamous marriages with neighboring groups like the Trio and Aparai, whose distinct Cariban dialects dilute monolingual Wayana fluency in households.[1] Historical mission schooling and contemporary state education policies prioritizing dominant languages have accelerated this shift, particularly among youth exposed to urban migration and media.[21] In Suriname, where Dutch-medium instruction is mandatory, fluency loss appears more pronounced than in French Guiana, where community attitudes toward indigenous languages remain relatively positive and bilingual exposure occurs in some remote settings.[22] Revitalization initiatives, including elder-led oral transmission in villages and documentation projects like the "Imilikut/Imenuru" program for Wayana-Aparai graphic art and language preservation in Brazil and French Guiana, aim to counter erosion but show limited empirical success in boosting youth proficiency, as they often emphasize cultural symbolism over scalable transmission strategies.[23] [24] These efforts, while commendable, face skepticism regarding long-term impact without enforced bilingual policies or incentives to prioritize Wayana in daily domains, as evidenced by persistent declines in similar Amazonian Cariban languages where external interventions prioritize documentation over active use.[25]Geographic distribution

Territories in Brazil

The Wayana presence in Brazil is concentrated in the northern state of Pará, primarily along the upper reaches of the Paru d'Este River within two contiguous indigenous lands: Terra Indígena Parque do Tumucumaque and Terra Indígena Rio Paru d'Este.[1] These territories, spanning forested highlands near the Tumucumaque Mountains, were administratively demarcated and homologated by federal decree on November 3, 1997, covering approximately 3,071 km² for Parque do Tumucumaque (extending into Amapá) and additional areas for Rio Paru d'Este, ratified under Brazil's constitutional protections for indigenous lands. The lands are managed by the National Indian Foundation (FUNAI), which enforces exclusive indigenous use and occupancy, though enforcement challenges persist due to remote access and border proximity.[26] Wayana communities in these territories number fewer than 500 individuals when combined with closely affiliated Aparai groups, reflecting historical migrations and low demographic density amid vast rainforests; pure Wayana subgroups comprise a smaller subset, often estimated at around 150, with villages like those in upper Paru hosting mixed settlements.[27] FUNAI policies emphasize territorial integrity, including recent expeditions in 2024 to reaffirm historical access to lower Paru areas displaced by non-indigenous settlers since the mid-20th century, fostering self-governance through associations like the Articulação de Mulheres Indígenas Wayana e Aparai.[26] However, post-2010s pressures from illegal gold mining have encroached, with proposals like the 2020 mining bill threatening up to 87% of Wayana-adjacent lands through deforestation and mercury pollution, prompting FUNAI interdictions despite limited resources.[28] Cross-border dynamics with Suriname are evident in seasonal mobility patterns, where Wayana groups traverse the Paru and adjacent rivers for hunting, fishing, and kin networks, complicating FUNAI's unilateral protections and highlighting the need for binational coordination to counter shared threats like unregulated resource extraction.[1] These movements underscore the territories' role as fluid extensions of broader Guianan indigenous spaces, yet Brazilian federal law prioritizes in-situ delineation to mitigate external incursions.[29]Territories in Suriname

The Wayana territories in Suriname occupy the southeastern interior of the country, centered along the Lawa, Litani, Oelemari, and upper Tapanahoni rivers, where communities maintain traditional livelihoods amid dense rainforest environments.[30] [6] These areas span approximately 24,865 square kilometers, encompassing vital habitats for foraging, agriculture, and seasonal mobility.[31] Wayana settlements include Apetina (also known as Puleowime), Paloemeu (Palumeu), Kawemhakan (Anapaike), and smaller sites such as Kumakupan, Lensedede, and Tutu Kampu, housing a total population of about 800 people distributed across these riverine villages.[7] [6] Despite continuous presence since migrations from Brazil in the mid-18th century, these lands lack formal legal titling from the Surinamese government, which has no specific legislation recognizing indigenous territorial rights—a situation persisting as the only such gap among tropical South American nations.[32] [33] This absence of delineation exposes territories to external pressures, including logging concessions that encroach without community consent, compounded by state delays in addressing petitions and international human rights rulings on demarcation.[34] [35] In response, Wayana groups have pursued self-directed measures, such as community mapping projects and customary consultation protocols, to document and defend claims independently of governmental processes.[31] [36] Kinship and resource-sharing networks extend across the Lawa River border into French Guiana, linking Surinamese Wayana with counterparts there and facilitating adaptive strategies amid unformalized status.[32] Such ties underscore the territories' role in broader cross-border ethnogenesis, yet underscore vulnerabilities arising from Suriname's inaction on titling, which hinders effective control over resource extraction and development incursions.[33][37]Territories in French Guiana

The Wayana maintain territories in the remote interior of French Guiana, concentrated along the upper Maroni River and its tributaries, including the Lawa River, which demarcate the border with Suriname. These areas encompass forested highlands and riverine environments integral to traditional Wayana mobility and resource use. Principal settlements include Twenke and Cayodé along the Lawa, Litani further upstream, and Taluhen and Antécume-Pata on the Maroni proper, forming approximately five villages sustained by river access for subsistence activities.[12][38] French Guiana's status as an overseas department integrates Wayana lands into national frameworks without designated indigenous reserves, unlike in neighboring countries; instead, territories overlap with protected zones under French environmental law, such as portions of the Parc amazonien de Guyane established on February 28, 2017, spanning over 6.7 million hectares of the interior. This park enforces conservation measures aligned with EU directives on biodiversity, restricting logging and mining while permitting regulated traditional practices, though enforcement relies on centralized authority rather than local control. French citizenship affords Wayana access to state services including infrastructure subsidies and social benefits, fostering partial economic incorporation but exerting assimilation pressures through mandatory French-language education and administrative dependencies that challenge autonomous decision-making.[39] Since the late 1990s, preliminary eco-tourism initiatives have emerged in Wayana areas, involving guided river expeditions and cultural demonstrations to generate supplementary income amid declining traditional foraging viability, though these remain small-scale and intermittently supported by regional development funds. Such efforts highlight tensions between preservation mandates and community needs, with EU-funded projects emphasizing sustainable resource use over full territorial sovereignty.[38]Social structure

Kinship systems and family organization

The Wayana kinship system employs bilateral descent, tracing relationships through both paternal and maternal lines, which fosters interconnected extended family networks across communities. This structure aligns with an Iroquois-type classification featuring bifurcate merging, where parallel cousins are treated as siblings and cross-cousins are potential spouses, facilitating affinal alliances that strengthen social ties.[40] Kinship terminology emphasizes generational continuity, particularly between grandparents and grandchildren, with terms like tamo (grandfather/elder) and tamusi (reference elder) underscoring hierarchical roles within families.[41] Post-marital residence is predominantly uxorilocal, with newlyweds residing with or near the wife's family, allowing children to remain integrated with maternal kin and promoting flexibility in response to village demographics and resource availability.[40] [42] This pattern supports extended family units comprising multiple generations, where grandparents assume key roles in child-rearing, hygiene, and cultural transmission, while mothers focus on early nurturing and fathers on skill-building in foraging activities.[40] Nuclear families form the core of households, often expanding to include affines through bride service, whereby grooms contribute labor or goods to in-laws, reinforcing resource-sharing and dispute mediation within kin groups.[41] Marriage preferences favor cross-cousin unions, particularly with the mother's brother's offspring, to consolidate alliances without formal ceremonies, though polygyny occurs among influential men, such as village leaders, who may wed multiple sisters to enhance political and economic leverage over resources like hunting grounds.[40] [41] Divorce is straightforward, typically involving the wife returning to her mother's household, which maintains matrilineal support networks amid flexible patrilineal tendencies observed in leadership inheritance.[42] These practices adapt to external pressures, prioritizing empirical kinship bonds over rigid descent groups.[41]Village composition and leadership roles

Wayana villages consist of small, kin-based settlements typically comprising 7 to 30 individuals organized into extended family units that span up to four generations.[1] [3] These units center on a married couple, their unmarried children, married daughters with sons-in-law, and grandchildren, exhibiting a tendency toward uxorilocal residence whereby sons-in-law reside with or near the wife's kin, though arrangements remain negotiable based on kinship ties.[1] Villages lack fixed clans or moieties, instead coalescing through dense, intergenerational kinship networks reinforced by marriage alliances and trade partnerships, which foster endogamous tendencies within local groups.[1] Leadership resides with a hereditary or founder-designated chief, termed pata esemy ("chief of the village") or tamuxi, whose tenure anchors the settlement's continuity; the chief's death often prompts village fission and relocation by constituent families.[1] [3] Chiefs exercise authority through persuasion, personal prestige, and mediation rather than hierarchy, coordinating practical tasks such as selecting house and garden sites, maintaining communal plazas, and organizing inter-village festivals, while designating co-residents (-poetory) as subordinates in a loose, consensus-oriented framework.[1] [13] For specialized endeavors like collective labor or rituals, temporary leaders known as aporesemy assume roles, ensuring adaptive governance without centralized coercion.[1] A distinguishing feature is the tukusipan, a large communal house or "prefecture" that serves as the village's focal point for assemblies, ceremonies, and guest accommodations, setting it apart from dispersed family dwellings where residents sleep in hammocks.[1] [13] This structure facilitates shared resource access, such as river ports and manioc processing facilities, underscoring the villages' emphasis on mutual aid amid autonomy.[1] Overall, the system supports fission-fusion patterns, enabling settlements to fragment and reform in response to chief mortality, resource pressures, or kinship realignments, thereby maintaining flexibility in low-density forest environments.[1] [3]Cultural practices

Spiritual beliefs and cosmology

The Wayana worldview is animistic, positing that nonhuman entities such as animals, rivers, and forests possess agency and spiritual potency equivalent to humans, influencing daily outcomes like health and hunting success through direct interactions observable in ethnographic accounts of spirit negotiations.[1][43] Spirits, including jorokó—destructive yet restorative forces manifesting in animals and capable of inducing sickness or death—require mediation to avert harm or secure benefits, as evidenced by hunter testimonies linking successful pursuits to prior shamanic interventions that appease these entities.[1] Wayana cosmology describes a non-hierarchical universe comprising the earth as a round island encircled by water, a subterranean realm inhabited by fur-clad beings under its own sun, and dual skies: a lower one (kapumereru) housing jorokó and kurumu spirits, and an upper firmament (kapu) containing Ikujuri—the pervasive creator-transformer principle that imbues beings with qualities shaping natural features like rivers and animal forms—alongside celestial bodies such as stars, the Sun, and Moon.[1] Human composition integrates into this framework via a tripartite structure: the physical body (punu), the vital principle (uzenu) that detaches during sleep to traverse spiritual domains, and the shade (omore); upon death, these elements disperse, with uzenu journeying to the celestial river xipahtai.[1] Shamans, known as pïjai, possess esoteric knowledge to dispatch their uzenu voluntarily for communication with spirits, negotiating with jorokó to cure ailments or enhance prowess, distinct from ordinary dreams where uzenu passively encounters ancestors or threats.[1][44] Ancestral influences persist through such dream voyages, where mythic forebears like the Kaikuxiana—jaguar-human hybrids from origin tales—impart guidance or warnings, empirically tied to real-world efficacy in foraging as per oral testimonies of predictive visions preceding bountiful yields.[1] This system underscores causal linkages between spiritual adherence and tangible survival, without reliance on abstracted moral hierarchies.[43]Rituals and oral traditions

The ëputop, also referred to as maraké in related contexts, constitutes a central male initiation ritual among the Wayana, involving adolescent boys undergoing repeated stings from ants or wasps to endure pain as a marker of maturation and eligibility for marriage.[45] Documented in mid-20th-century ethnographies, this rite entails periods of seclusion where initiates confront physical trials, fostering resilience and integrating them into adult social roles while strengthening inter-village ties through collective participation.[46] The ritual's structure emphasizes performative endurance over symbolic abstraction, empirically aiding group cohesion by publicly validating participants' commitment to communal norms amid environmental and social pressures.[47] Integral to ëputop are kalawu chants, ritual songs comprising 13 sequential episodes recited during the proceedings to transmit cosmological and migratory narratives that anchor Wayana ethnic identity.[48] These oral performances, often led by elders, recount ancestral journeys across the Guiana Shield—such as displacements from upstream rivers due to conflicts or resource shifts—serving as dynamic repositories of historical knowledge rather than static lore.[49] By embedding such epics in enacted ceremonies, the Wayana adapt traditions to contemporary contexts, using them to reaffirm alliances and cultural continuity despite external disruptions like missionary contact since the early 20th century.[46] Feast-like assemblies during these rituals feature rhythmic music from flutes and drums alongside temporary body paintings derived from natural pigments, which visually signal participants' ritual status and facilitate social synchronization.[50] Such elements, verifiable through ethnographic audio recordings from the 1970s onward, underscore the rituals' utility in forging reciprocal bonds, as hosts provide sustenance and performers exchange narratives to mitigate isolation in dispersed settlements.[49] This performative framework prioritizes observable social functions—enhanced cooperation and identity reinforcement—over interpretive mysticism, aligning with the Wayana's adaptive strategies in lowland Amazonian ecologies.[41]Material culture and technology

The Wayana build oval communal houses called tukusipan, serving as central gathering spaces for meetings and storage of ceremonial items, constructed with paxiúba palm wood walls and thatched roofs from ubim or bacaba leaves to withstand humid riverine conditions.[1] Family residences include variants such as tahkuekemy (one-story with raised wooden floorboards for protection against ground moisture) and tymanakemy (two-story structures), both oval in plan and adapted for extended kin groups along floodplain-adjacent rivers.[1] These designs emphasize durability against seasonal water levels, with open layouts facilitating airflow in tropical heat.[41] Men specialize in crafting dugout canoes (pirogue) by felling and hollowing local hardwoods through controlled burning and adzing, a labor-intensive process often performed as uxorilocal service, enabling transport on rivers like the Maroni and Tapanahoni.[1] [51] Hunting technology features blowguns (pïka) fashioned from straight wooden tubes fitted with poisoned darts, targeting monkeys, birds, and rodents with curare-tipped projectiles for precise, silent kills in dense forest.[52] [3] Basketry, primarily men's work using arumã reeds gathered on forest expeditions, yields utilitarian carriers, sieves, and house fittings like erohtopo tapyiny wall panels, often adorned with geometric motifs symbolizing natural patterns such as animal tracks.[1] [41] Women produce cotton hammocks via finger-weaving techniques, suspended between house posts for sleeping and child-carrying, integral to daily rest in communal settings.[1] Following European contact in the 19th century, Wayana integrated metal tools such as axes, machetes, and graters via trade with coastal groups and missionaries, accelerating woodwork, garden clearance, and cassava processing while retaining traditional forms like wooden adzes for fine shaping.[1] [53] Shotguns supplemented blowguns for larger game by the early 20th century, adopted pragmatically without full displacement of indigenous methods, as evidenced by ongoing canoe fabrication and basketry production.[1] [54]Economy and subsistence

Traditional foraging and agriculture

The Wayana traditionally practiced slash-and-burn agriculture, clearing forest plots during the dry season (July to December) by felling trees and burning vegetation to enrich the soil with ash, followed by planting in the subsequent rainy period. Primary crops included bitter and sweet manioc (Manihot esculenta), from which women processed flour, flatbreads (kasiri), and fermented beverages through grating, pressing, and roasting to remove cyanogenic compounds; supplementary plants encompassed sweet potatoes, yams, bananas, maize, and fruit trees like mango and citrus, cultivated in family-managed gardens rotated across 1-3 plots per household to maintain soil fertility via extended fallows averaging 25 years.[1][55] This horticulture was supplemented by foraging for wild resources, including açaí berries, bacaba fruits, wild honey, insect larvae, turtle eggs, and forest tubers, which provided seasonal caloric boosts and micronutrients amid the manioc-dominant diet. Hunting targeted large game such as peccaries, tapirs, deer, and howler monkeys, alongside smaller prey like pacas, agoutis, curassows, and macaws, using bows, arrows, blowguns, and collective expeditions lasting weeks to stockpile meat for festivals; these activities yielded protein-dense foods integral to nutritional balance, with no evidence of overexploitation in traditional low-density populations due to territorial ranging and taboos on certain species.[1] Fishing complemented these pursuits, employing hooks, woven nets, barbed arrows, and timbó (rotenone-based plant poison) during dry-season low waters to stun and harvest schooling fish like tucunaré (peacock bass), pacu, piranhas, and catfishes in riverine pools and tributaries. Gender divisions structured labor efficiency: men predominantly cleared fields, hunted, and fished using mobile techniques, while women handled crop planting, harvesting, manioc processing, and stationary gathering, enabling parallel resource acquisition that supported household self-sufficiency without domestication of livestock beyond occasional fowl for eggs.[1] Seasonal cycles aligned activities for resilience—dry periods favored hunting and poison fishing as rivers receded, concentrating prey, while wet seasons emphasized garden tending and wild fruit collection—resulting in a diversified subsistence where wild-sourced proteins and fats from hunting and fishing comprised a substantial dietary share alongside carbohydrate-heavy cultivated roots, affirming adaptive sustainability through empirical indicators like prolonged fallow recovery and minimal historical surpluses traded.[1][55]Adaptations to external economies

Since the late 1980s, limited ecotourism initiatives in French Guiana have offered Wayana communities supplementary income through guided forest tours and demonstrations of traditional practices, such as crafting and storytelling, though French authorities restrict access to select villages like Twenke and Koumakan to mitigate cultural disruption.[13][56] These activities generate cash for purchasing manufactured goods unavailable via subsistence, but participation risks commodifying sacred rituals and accelerating youth disinterest in ancestral knowledge, as observed in broader indigenous tourism dynamics.[57] Interactions with small-scale gold miners, particularly along the Lawa and Maroni rivers bordering Suriname and French Guiana, involve Wayana bartering bushmeat, fish, and forest products for tools, fuel, and processed foods since the 1990s mining surge, providing immediate economic liquidity amid sparse formal markets.[58] However, this exchange sustains environmental degradation, including mercury bioaccumulation in fish stocks—a primary protein source—leading to documented neurological risks in Wayana populations, with blood mercury levels exceeding WHO thresholds in southeastern Suriname communities by 2014.[59][60] Such trade bolsters short-term material access but erodes long-term subsistence viability through river contamination and habitat loss.[61] Wage labor opportunities remain marginal for Wayana, concentrated in French Guiana's proximity to European welfare systems, where some individuals secure seasonal employment in construction or administration, yielding higher remittances than in Suriname or Brazil; yet, across borders, formal jobs constitute under 10% of livelihoods as of 2007 assessments.[62][32] In Brazilian reserves near the Paru River, sparse participation in extractive or agricultural wage work shows uneven outcomes, with cash inflows funding rifles and outboard motors but correlating with generational shifts away from hunting, resulting in neither widespread prosperity nor sustained cultural continuity.[1][63] Overall, these adaptations hybridize economies, enhancing individual agency for select goods while imposing asymmetric costs on communal resource bases.Political organization

Traditional governance mechanisms

The Wayana maintain village-level autonomy in their traditional political organization, with each settlement typically centered around a chief (known as tamusi, kapitein, or granman) who holds authority derived from personal prestige, ritual expertise, and kinship ties rather than coercive power. Villages, ranging from 15 to 150 inhabitants, operate independently, relocating periodically—every 10 to 15 years—due to resource depletion or social disruptions like deaths, without centralized oversight from larger polities. This structure persisted into the 20th century, as observed in ethnographic accounts from the 1930s to 1960s documenting chiefs such as Janamale and Twenke leading isolated communities along rivers in French Guiana and Suriname.[41][1] Decision-making emphasizes deliberation and consensus, convened in communal roundhouses (tukusipan) or public plazas, where the chief facilitates discussions on matters like resource allocation, rituals, and conflict resolution, often incorporating input from elders and shamans. While chiefs can issue unilateral directives in crises, such as ordering relocations or punitive actions, enforcement relies on communal adherence and the leader's shamanic prestige, as shamans (pïjai) mediate spiritual dimensions, prophesy outcomes, and impose taboos that underpin social order. For instance, 20th-century observations note chiefs like Kailawa directing expeditions or killings, justified through ritual authority rather than formal hierarchy.[41] Customary laws govern resource sharing and sustainability, mandating communal labor for agriculture—primarily slash-and-burn cassava cultivation—and enforcing taboos against overexploitation, such as restrictions on hunting in spirit-haunted areas or food prohibitions during rites to prevent ecological imbalance. These norms, transmitted orally by elders, promote equitable distribution, with surpluses directed toward collective rituals like the maraké initiation, fostering social cohesion without codified penalties beyond ostracism or spiritual sanctions. Village dispersion often follows a chief's death, underscoring the system's dependence on living leaders' ability to sustain consensus.[41][1]Relations with state authorities

In French Guiana, the Wayana acquired French citizenship following the territory's departmentalization in 1946, which integrated indigenous populations into the French administrative framework and provided access to social services, though initial resistance to assimilation persisted among groups like the Wayana.[12] This status contrasts with limited land rights, as the French state retains ownership of over 90% of the territory, including Wayana-occupied areas, leading to ongoing tensions over resource management without formal indigenous titling.[64] Relations with Surinamese authorities have been characterized by governmental neglect, including the absence of land rights recognition and failure to ratify ILO Convention 169, which mandates free, prior, and informed consent for projects affecting indigenous territories.[65] This has enabled unchecked illegal gold mining and logging on Wayana lands in the southern interior, with minimal state policing or enforcement, exacerbating environmental degradation and health risks without compensatory negotiations.[66] Suriname's centralized approach installs appointed captains as intermediaries, but pragmatic cross-border movements by Wayana—facilitated by shared riverine territories—have occasionally leveraged binational ties to pressure authorities, though unfulfilled promises on infrastructure and protection persist.[67] In Brazil, Wayana engagements involve federal land demarcation processes under the 1988 Constitution, with territories such as Rio Paru d'Este Indigenous Land identified for Wayana and neighboring groups in the Tumucumaque region, though implementation has faced delays and invasions.[68] Despite Brazil's ratification of ILO 169 in 2002, enforcement remains inconsistent, as evidenced by systematic violations reported to the ILO, including inadequate consultations on extractive activities near borders.[69] Wayana communities have pragmatically negotiated demarcations by mapping traditional areas using indigenous knowledge alongside technology, highlighting treaty shortfalls where state benevolence is undermined by competing resource interests.[68] Across the tri-national borderlands, Wayana relations emphasize pragmatic border-leveraging amid treaty failures, such as Suriname's non-ratification and limited ILO 169 application in Brazil and France (which has not ratified the convention), resulting in sporadic consultations on mining rather than robust enforcement.[65] For instance, 2010s resource disputes, including gold extraction impacts, have prompted ad hoc binational dialogues but yielded few binding outcomes, underscoring states' prioritization of centralization over indigenous autonomy.[70]Demographics and health

Population estimates by country

In Brazil, the Wayana population is estimated at 254 individuals as of 2020, according to data from the Secretaria Especial de Saúde Indígena (SESAI) compiled by the Instituto Socioambiental; this figure primarily reflects contacted groups in the northern Amazon, often residing alongside related Aparai peoples in territories like Rio Paru d'Este.[71] In Suriname, ethnographic assessments place the Wayana at approximately 500, concentrated in small riverside settlements along the Lawa and Tapanahoni rivers, though exact census data remains limited due to the country's infrequent national surveys of indigenous groups.[72] In French Guiana, the population is estimated at around 1,000 to 1,100, mainly in the interior along the Maroni and Oyapock river systems, drawing from field-based counts by organizations monitoring Amerindian communities.[73][2] These figures yield a total Wayana population of under 2,000, subject to variability from cross-border mobility, interethnic marriages, and semi-isolated subgroups that evade systematic enumeration; methodological critiques highlight potential underreporting in remote areas, as reliance on self-identification and sporadic village visits can miss transient or uncontacted kin networks.[7]| Country | Estimate | Year/Source |

|---|---|---|

| Brazil | 254 | 2020, SESAI/Instituto Socioambiental[71] |

| Suriname | 500 | Recent ethnographic (Joshua Project)[72] |

| French Guiana | 1,100 | Recent field assessments (Joshua Project/Survival International)[2][73] |