Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

1888 Barcelona Universal Exposition

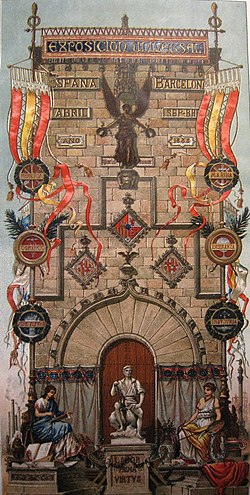

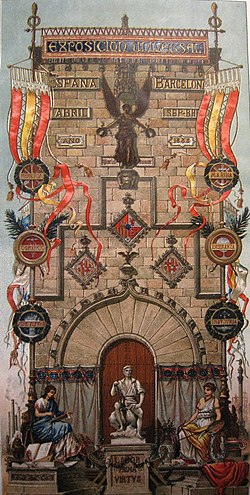

View on Wikipedia| 1888 Barcelona | |

|---|---|

Official Poster | |

| Overview | |

| BIE-class | Universal exposition |

| Category | Historical Expo |

| Name | Exposició Universal de Barcelona / Exposición Universal de Barcelona |

| Building(s) | Arc de Triomf |

| Area | 46.5 ha |

| Visitors | 2.300.000 |

| Organized by | Tomàs Moragas (artistic director) |

| Participant(s) | |

| Countries | 30 |

| Location | |

| Country | Spain |

| City | Barcelona |

| Venue | Parc de la Ciutadella |

| Coordinates | 41°23′17″N 2°11′15″E / 41.38806°N 2.18750°E |

| Timeline | |

| Opening | 8 April 1888 |

| Closure | 10 December 1888 |

| Universal expositions | |

| Previous | Melbourne International Exhibition (1880) in Melbourne |

| Next | Exposition Universelle (1889) in Paris |

The 1888 Barcelona Universal Exposition (in Catalan: Exposició Universal de Barcelona and Exposición Universal de Barcelona in Spanish) was Spain's first International World's Fair[1] and ran from 8 April to 9 December 1888.[2] The second one in Barcelona was held in 1929.

Summary

[edit]

Eugenio Serrano de Casanova (journalist, writer and entrepreneur) tried to launch an exposition in 1886, and when that failed, the Mayor of Barcelona, Francesc Rius i Taulet, took over[1] the planning of the project. The fair was hosted on the reconstructed 115-acre (47 ha) site of the city's main public park, the Parc de la Ciutadella, with Vilaseca's Arc de Triomf forming the entrance.[1] More than 2 million people from Spain, the rest of Europe, and other international points of embarkation visited the exhibition,[3] which made the equivalent of $1,737,000 USD.[2] The fair was opened by Alfonso XIII of Spain and Maria Christina of Austria.[1] Twenty-seven countries participated, including China, Japan and the United States.[3]

Contents

[edit]The piano manufacturer Erard sponsored a series of 20 concerts featuring Isaac Albéniz, a Catalan pianist and composer best known for his piano works based on folk music idioms.[4] The artistic director was Tomàs Moragas.[5]

Luisa Lacal de Bracho won a gold medal and Josep Maria Tamburini won a silver medal at the exhibition.[6]

Legacy and surviving monuments

[edit]The main legacy of the 1888 World Fair is the Ciutadella Park: the World Fair served as the opportunity for Barcelona to rid itself of the hated citadel and transform it into a central park for the city's denizens. The entire Ciutadella Park in its present layout is a product of the World Fair, with its monumental fountain and small ponds, its Castell dels tres dracs (Castle of the Three Dragons) built by Domènech i Montaner to house the World Fair's café / restaurant, which later served to house the Zoology Museum, Hivernacle (Glasshouse or Greenhouse), the classicist Geology Museum and the Umbracle (a remarkable shaded structure for plants).

Another product of the World Fair is the Modernista or Neo-Mudéjar Arc de Triomf (triumphal arch), the Fair's former gateway, presiding over Passeig de Lluís Companys.

The Columbus Monument (Monument a Colom), a 60 m (197 ft) tall monument to Christopher Columbus, was built for the exposition on the site where Columbus returned to Europe after his first voyage to the Americas. It was erected at the lower end of Les Rambles and remains standing today.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Pelle, Kimberley D. "Barcelona 1888". In Findling, John E (ed.). Encyclopedia of World's Fairs and Expositions. McFarland & Company, Inc. p. 94. ISBN 978-0-7864-3416-9.

- ^ a b Pelle, Kimberley D. "Appendix B:Fair Statistics". In Findling, John E (ed.). Encyclopedia of World's Fairs and Expositions. McFarland & Company, Inc. p. 414. ISBN 978-0-7864-3416-9.

- ^ a b Pelle, Kimberley D. "Barcelona 1888". In Findling, John E (ed.). Encyclopedia of World's Fairs and Expositions. McFarland & Company, Inc. p. 95. ISBN 978-0-7864-3416-9.

- ^ "Frances Barulich. Albéniz, Isaac".

- ^ "Moragas y Torras, Tomás - Museo Nacional del Prado". Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ "Josep Maria Tamburini i Dalmau | enciclopèdia.cat" (in Catalan). Retrieved 19 June 2020.

External links

[edit]- Official website of the BIE

- THE WORLD’S FAIR 1888

- Overview / brief history of the 1888 Barcelona Universal Expo on the GenCat website (in English, Catalan, Occitan, Spanish and French).

1888 Barcelona Universal Exposition

View on GrokipediaThe 1888 Barcelona Universal Exposition was Spain's inaugural international world's fair, held from 8 April to 10 December 1888 in the Parc de la Ciutadella to promote industrial, artistic, and cultural advancements amid the city's rapid urbanization.[1][2] Organized under the regency of Maria Cristina following the death of Alfonso XII, the event featured exhibits from 30 countries across 46.5 hectares, emphasizing fine and industrial arts while serving as a catalyst for demolishing Barcelona's medieval walls and expanding infrastructure like the Arc de Triomf as its grand entrance.[3][1][4] Attracting over two million visitors during its 246-day run, the exposition highlighted Catalan industrial prowess and bourgeois aspirations, with notable pavilions showcasing machinery, textiles, and decorative arts that foreshadowed the rise of Modernisme in architecture and design.[5][2] It spurred significant urban renewal, transforming former military grounds into public parks and boulevards, thereby embedding lasting landmarks and boosting Barcelona's global profile as a modern European hub.[6][7] The fair's success, despite economic challenges, underscored the interplay of state patronage and local initiative in fostering economic growth and cultural identity without notable controversies, though it reflected tensions between central Spanish authority and regional Catalan ambitions.[8]