Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

MOS Technology 6502

View on Wikipedia | |

| General information | |

|---|---|

| Launched | 1975 |

| Common manufacturer | |

| Performance | |

| Max. CPU clock rate | 1 MHz to 3 MHz |

| Data width | 8 bits |

| Address width | 16 bits |

| Architecture and classification | |

| Instruction set | MOS 6502 |

| Number of instructions | 56 (55 originally) |

| Physical specifications | |

| Transistors | |

| Package |

|

| History | |

| Predecessors |

|

| Successors | |

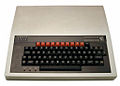

The MOS Technology 6502 (typically pronounced "sixty-five-oh-two" or "six-five-oh-two")[3] is an 8-bit microprocessor that was designed by a small team led by Chuck Peddle for MOS Technology and was launched in September 1975. The design team had formerly worked at Motorola on the Motorola 6800 project; the 6502 is essentially a simplified, less expensive and faster version of that design using depletion-load NMOS technology that made using the microchip in computers much cheaper.

When it was introduced, the 6502 was the least expensive microprocessor on the market by a considerable margin. It initially sold for less than one-sixth the cost of competing designs from larger companies, such as the 6800 or Intel 8080. Its introduction caused rapid decreases in pricing across the entire processor market. Along with the Zilog Z80, it sparked a series of projects that resulted in the home computer revolution of the early 1980s.

Home video game consoles and home computers of the 1970s through the early 1990s, such as the Atari 2600, Atari 8-bit computers, Apple II, Nintendo Entertainment System, Commodore 64, Atari Lynx, BBC Micro and others, use the 6502 or variations of the basic design. Soon after the 6502's introduction, MOS Technology was purchased outright by Commodore International, who continued to sell the microprocessor and licenses to other manufacturers. In the early days of the 6502, it was second-sourced by Rockwell and Synertek, and later licensed to other companies.

In 1981, the Western Design Center started development of a CMOS version, the 65C02. This continues to be widely used in embedded systems, with estimated production volumes in the hundreds of millions.[4]

History and use

[edit]Conception

[edit]The origins of the 6502 chip date back to 1960, after the Soviet Union launched the first artificial Earth satellite – the Sputnik 1. During this time, Chuck Peddle worked at General Electric as an engineer-in-training, designing tests and systems for missiles and spaceships. As he advanced into his engineering career, he found room-sized computers to be a flawed model of centralized intelligence, and instead, considered distributing it locally. However, General Electric sold its computer division to Honeywell in 1970, liquidating the entire section he worked in.[5]

Undeterred, Peddle took this severance and started his own company in 1972 to make intelligent terminals for word-processing.[6][7] Shortly after, Peddle found himself in a technological struggle; even though electronics were evolving at the time, it was still ridiculously complex to run the system he conceived. His idea required a microprocessor that would be capable of running programs. However, many companies were competing on the same technology for the same reason, including Motorola.[7]

Origins at Motorola

[edit]

Motorola started the 6800 microprocessor project in 1971 with Tom Bennett as the main architect. Motorola's engineers could run analog and digital simulations on an IBM 370-165 mainframe computer.[8] The chip layout began in late 1972, the first 6800 chips were fabricated in February 1974 and the full family was officially released in November 1974.[9][10]

John Buchanan was the designer of the 6800 chip[11][12] and Rod Orgill, who later did the 6501, assisted Buchanan with circuit analyses and chip layout.[13] Bill Mensch joined Motorola in June 1971 after graduating from the University of Arizona (at age 26).[14] His first assignment was helping define the peripheral ICs for the 6800 family and later he was the principal designer of the 6820 Peripheral Interface Adapter (PIA).[15] Bennett hired Chuck Peddle in 1973 to do architectural support work on the 6800 family products already in progress.[16] He contributed in many areas, including the design of the 6850 ACIA (serial interface).[17]

Motorola's target customers were established electronics companies such as Hewlett-Packard, Tektronix, TRW, and Chrysler.[18] In May 1972, Motorola's engineers began visiting select customers and sharing the details of their proposed 8-bit microprocessor system with ROM, RAM, parallel and serial interfaces.[19] In early 1974, they provided engineering samples of the chips so that customers could prototype their designs. Motorola's "total product family" strategy did not focus on the price of the microprocessor, but on reducing the customer's total design cost. They offered development software on a timeshare computer, the "EXORciser" debugging system, onsite training and field application engineer support.[20][21] Both Intel and Motorola had initially announced a US$360 price for a single microprocessor.[22][23] The actual price for production quantities was much less. Motorola offered a design kit containing the 6800 with six support chips for US$300.[24]

Peddle, who would accompany the salespeople on customer visits, found that customers were put off by the high cost of the microprocessor chips.[25] At the same time, these visits invariably resulted in the engineers he presented to producing lists of required instructions that were much smaller than "all these fancy instructions" that had been included in the 6800.[26] Peddle and other team members started outlining the design of an improved feature, reduced-size microprocessor. At that time, Motorola's new semiconductor fabrication facility in Austin, Texas, was having difficulty producing MOS chips, and mid-1974 was the beginning of a year-long recession in the semiconductor industry. Also, many of the Mesa, Arizona employees were displeased with the upcoming relocation to Austin.[27]

Motorola's Semiconductor Products Division management showed no interest in Peddle's low-cost microprocessor proposal. Eventually, Peddle was given an official letter telling him to stop working on the system.[28] Peddle responded to the order by informing Motorola that the letter represented an official declaration of "project abandonment", and as such, the intellectual property he had developed to that point was now his.[29] The 6502 was designed by many of the same engineers that had designed the Motorola 6800 microprocessor family.[30]

In a November 1975 interview, Motorola's Chairman, Bob Galvin, ultimately agreed that Peddle's concept was a good one and that the division missed an opportunity, "We did not choose the right leaders in the Semiconductor Products division." The division was reorganized and the management replaced. The new group vice president John Welty said, "The semiconductor sales organization lost its sensitivity to customer needs and couldn't make speedy decisions."[31]

MOS Technology

[edit]

Peddle began looking outside Motorola for a source of funding for this new project. He initially approached Mostek CEO L. J. Sevin, but was declined. Sevin later admitted this was because he was afraid Motorola would sue them.[32]

While Peddle was visiting Ford Motor Company on one of his sales trips, Bob Johnson, later head of Ford's engine automation division, mentioned that their former colleague John Paivinen had moved to General Instrument and taught himself semiconductor design.[33] Paivinen then formed MOS Technology in Valley Forge, Pennsylvania in 1969 with two other executives from General Instrument, Mort Jaffe and Don McLaughlin. Allen-Bradley, a supplier of electronic components and industrial controls, acquired a majority interest in 1970.[34] The company designed and fabricated custom ICs for customers and had developed a line of calculator chips.[35]

After the Mostek efforts fell through, Peddle approached Paivinen, who "immediately got it".[36] On 19 August 1974, Chuck Peddle, Bill Mensch, Rod Orgill, Harry Bawcom, Ray Hirt, Terry Holdt, and Wil Mathys left Motorola to join MOS. Mike Janes joined later. Of the seventeen chip designers and layout people on the 6800 team, eight left. The goal of the team was to design and produce a low-cost microprocessor for embedded applications and to target as wide as possible a customer base. This would be possible only if the microprocessor was low cost, and the team set the price goal for volume purchases at $5.[37] Mensch later stated the goal was not the processor price itself, but to create a set of chips that could sell at $20 to compete with the recently introduced Intel 4040 that sold for $29 in a similar complete chipset.[38]

Chips are produced by printing multiple copies of the chip design on the surface of a wafer, a thin disk of highly pure silicon. Smaller chips can be printed in greater numbers on the same wafer, decreasing their relative price. Additionally, wafers always include some number of tiny physical defects that are scattered across the surface. Any chip printed in that location will fail and has to be discarded. Smaller chips mean any single copy is less likely to be printed on a defect. For both of these reasons, the cost of the final product is strongly dependent on the size of the chip design.[39]

The original 6800 chips were intended to be 180 by 180 mils (4.6 mm × 4.6 mm), but layout was completed at 212 by 212 mils (5.4 mm × 5.4 mm), or an area of 29.0 mm2.[40] For the new design, the cost goal demanded a size goal of 153 by 168 mils (3.9 mm × 4.3 mm), or an area of 16.6 mm2, roughly half that of the 6800.[41] Several new techniques would be needed to hit this goal.

Moving to NMOS

[edit]Two significant advances arrived in the market just as the 6502 was being designed that provided significant cost reductions. The first was the move to depletion-load NMOS. The 6800 used an early NMOS process, enhancement mode, that required three supply voltages. One of the 6800's headlining features was an onboard voltage doubler that allowed a single +5 V supply be used for +5, −5 and +12 V internally, as opposed to other chips of the era like the Intel 8080 that required three separate supply pins.[42] While this feature reduced the complexity of the power supply and pin layout, it still required separate power line to the various gates on the chip, driving up complexity and size. By moving to the new depletion-load design, a single +5 V supply was all that was needed, eliminating all of this complexity.[43]

A further advantage was that depletion-load designs used less power while switching, thus running cooler and allowing higher operating speeds. Another practical offshoot is that the clock signal for earlier CPUs had to be strong enough to survive all the dissipation as it traveled through the circuits, which almost always required a separate external chip that could supply a powerful signal. With the reduced power requirements of depletion-load design, the clock could be moved onto the chip, simplifying the overall computer design. These changes greatly reduced complexity and the cost of implementing a complete system.[43]

A wider change taking place in the industry was the introduction of projection masking. Previously, chips were patterned onto the surface of the wafer by placing a mask on the surface of the wafer and then shining a bright light on it. The masks often picked up tiny bits of dirt or photoresist as they were lifted off the chip, causing flaws in those locations on any subsequent masking. With complex designs like CPUs, 5 or 6 such masking steps would be used, and the chance that at least one of these steps would introduce a flaw was very high. In most cases, 90% of such designs were flawed, resulting in a 10% yield. The price of the working examples had to cover the production cost of the 90% that were thrown away.[44]

In 1973, Perkin-Elmer introduced the Micralign system, which projected an image of the mask on the wafer instead of requiring direct contact. Masks no longer picked up dirt from the wafers and lasted on the order of 100,000 uses rather than 10. This eliminated step-to-step failures and the high flaw rates formerly seen on complex designs. Yields on CPUs immediately jumped from 10% to 60 or 70%. This meant the price of the CPU declined roughly the same amount and the microprocessor suddenly became a commodity device.[44]

MOS Technology's existing fabrication lines were based on the older PMOS technology, they had not yet begun to work with NMOS when the team arrived. Paivinen promised to have an NMOS line up and running in time to begin the production of the new CPU. He delivered on the promise, the new line was ready by June 1975.[45]

Design notes

[edit]Chuck Peddle, Rod Orgill, and Wil Mathys designed the initial architecture of the new processors. A September 1975 article in EDN magazine gives this summary of the design:[46]

The MOS Technology 650X family represents a conscious attempt of eight former Motorola employees who worked on the development of the 6800 system to put out a part that would replace and outperform the 6800, yet undersell it. With the benefit of hindsight gained on the 6800 project, the MOS Technology team headed by Chuck Peddle, made the following architectural changes in the Motorola CPU…

The main change in terms of chip size was the elimination of the tri-state drivers from the address bus outputs. A three-state bus has states for 1, 0 and high impedance. The last state is used to allow other devices to access the bus, and is typically used for multiprocessing, or more commonly in these roles, for direct memory access (DMA). While useful, this feature is expensive in terms of on-chip circuitry. The 6502 simply removed this feature, in keeping with its design as an inexpensive controller being used for specific tasks and communicating with simple devices. Peddle suggested that anyone who required this style of access could implement it with a 74158.[47][a]

The next major difference was to simplify the registers. To start with, one of the two accumulators was removed. General-purpose registers like accumulators have to be accessed by many parts of the instruction decoder, and thus require significant amounts of wiring to move data to and from their storage. Two accumulators makes many coding tasks easier but costs the chip design itself significant complexity.[46] Further savings were made by reducing the stack register from 16 to 8 bits, meaning that the stack could only be 256 bytes long, which was enough for its intended role as a microcontroller.[46][failed verification]

The 16-bit IX index register was split in two, becoming X and Y. More importantly, the style of access changed. In the 6800, IX held a 16-bit address which was offset by an 8-bit number stored with the instruction and added to the address. In the 6502 (and most other contemporary designs), the 16-bit base address was stored in the instruction, and the 8-bit X or Y was added to it.[47]

Finally, the instruction set was simplified, simplifying the decoder and control logic. Of the original 72 instructions in the 6800, 56 were implemented. Among those removed were instructions that operated between the 6800's two accumulators, and several branch instructions inspired by the PDP-11.[47]

The chip's high-level design had to be turned into drawings of transistors and interconnects. At MOS Technology, the layout was a very manual process done with colored pencils and vellum paper. The layout consisted of thousands of polygon shapes on six different drawings; one for each layer of the fabrication process. Given the size limits, the entire chip design had to be constantly considered. Mensch and Paivinen worked on the instruction decoder[49] while Mensch, Peddle and Orgill worked on the ALU and registers. A further advance, developed at a party, was a way to share some of the internal wiring to allow the ALU to be reduced in size.[50]

Despite their best efforts, the final design ended up being larger than the original target. The first 6502 chips were 168 by 183 mils (4.3 mm × 4.6 mm), for an area of 19.8 mm2. The original version of the processor had no rotate right (ROR) capability, so the instruction was omitted from the original documentation. The next iteration of the design shrank the chip and added the rotate right capability, and ROR was included in revised documentation.[51][b]

Introducing the 6501 and 6502

[edit]

MOS would introduce two microprocessors based on the same underlying design: the 6501 would plug into the same socket as the Motorola 6800, while the 6502 re-arranged the pinout to support an on-chip clock oscillator. Both would work with other support chips designed for the 6800. They would not run 6800 software because they had a different instruction set, different registers, and mostly different addressing modes.[3] Rod Orgill was responsible for the 6501 design; he had assisted John Buchanan at Motorola on the 6800. Bill Mensch did the 6502; he was the designer of the 6820 PIA at Motorola. Harry Bawcom, Mike Janes and Sydney-Anne Holt helped with the layout.

MOS Technology's microprocessor introduction was different from the traditional months-long product launch. The first run of a new integrated circuit is normally used for internal testing and shared with select customers as engineering samples. These chips often have minor design defects that will be corrected before production begins. Chuck Peddle's goal was to sell the first run 6501 and 6502 chips to the attendees at the WESCON trade show in San Francisco beginning on September 16, 1975. Peddle was a very effective spokesman and the MOS Technology microprocessors were extensively covered in the trade press. One of the earliest was a full-page story on the MCS6501 and MCS6502 microprocessors in the July 24, 1975 issue of Electronics magazine.[55] Stories also ran in EE Times (August 24, 1975),[56] EDN (September 20, 1975), Electronic News (November 3, 1975), Byte (November 1975)[57] and Microcomputer Digest (November 1975).[58] Advertisements for the 6501 appeared in several publications the first week of August 1975. The 6501 would be for sale at WESCON for $20 each.[59] In September 1975, the advertisements included both the 6501 and the 6502 microprocessors. The 6502 would cost only $25 (equivalent to $146 in 2024).[60]

When MOS Technology arrived at Wescon, they found that exhibitors were not permitted to sell anything on the show floor. They rented the MacArthur Suite at the St. Francis Hotel and directed customers there to purchase the processors. At the suite, the processors were stored in large jars to imply that the chips were in production and readily available. The customers did not know the bottom half of each jar contained non-functional chips.[61] The chips were $20 and $25 while the documentation package was an additional $10. Users were encouraged to make photocopies of the documents, an inexpensive way for MOS Technology to distribute product information. The preliminary data sheets listed just 55 instructions and excluded the Rotate Right (ROR) instruction, which was not supported on these early chips. The reviews in Byte and EDN noted the lack of the ROR instruction. The next revision of the layout fixed this problem and the May 1976 datasheet listed 56 instructions. Peddle wanted every interested engineer and hobbyist to have access to the chips and documentation, whereas other semiconductor companies only wanted to deal with "serious" customers. For example, Signetics was introducing the 2650 microprocessor and its advertisements asked readers to write for information on their company letterhead.[62]

Motorola lawsuit

[edit]

The 6501/6502 introduction in print and at Wescon was a success. The press coverage got Motorola's attention, precipitating pricing adjustments and lawsuits. In October 1975, Motorola reduced the price of a single 6800 microprocessor from $175 to $69. The $300 system design kit was reduced to $150 and it now came with a printed circuit board.[63] On November 3, 1975, Motorola sought an injunction in Federal Court to stop MOS Technology from making and selling microprocessor products. They also filed a lawsuit claiming patent infringement and misappropriation of trade secrets. Motorola claimed that seven former employees joined MOS Technology to create that company's microprocessor products.[64]

Motorola was a billion-dollar company with a plausible case and expensive lawyers. On October 30, 1974, Motorola had filed numerous patent applications on the microprocessor family and was granted twenty-five patents. The first was in June 1976 and the second was to Bill Mensch on July 6, 1976, for the 6820 PIA chip layout. These patents covered the 6800 bus and how the peripheral chips interfaced with the microprocessor.[65] Motorola began making transistors in 1950 and had a portfolio of semiconductor patents. Allen-Bradley decided not to fight this case and sold their interest in MOS Technology back to the founders. Four of the former Motorola engineers were named in the suit: Chuck Peddle, Will Mathys, Bill Mensch and Rod Orgill. All were named inventors in the 6800 patent applications. During the discovery process, Motorola found that one engineer, Mike Janes, had ignored Peddle's instructions and brought his 6800 design documents to MOS Technology.[66] In March 1976, the now independent MOS Technology was running out of money and had to settle the case. They agreed to drop the 6501 processor, pay Motorola $200,000 and return the documents that Motorola contended were confidential. Both companies agreed to cross-license microprocessor patents.[67] That May, Motorola dropped the price of a single 6800 microprocessor to $35. By November, Commodore had acquired MOS Technology.[68][69]

Computers and games

[edit]With legal troubles behind them, MOS was still left with the problem of getting developers to try their processor, prompting Chuck Peddle to design the MDT-650 (microcomputer development terminal) single-board computer. Another group inside the company designed the KIM-1, which was sold semi-complete and could be turned into a usable system with the addition of a 3rd party computer terminal and compact cassette drive. While it sold well to its intended market, the company found the KIM-1 also sold well to hobbyists and tinkerers. The related Rockwell AIM-65 control, training, and development system also did well. The software in the AIM 65 was based on that in the MDT. Another roughly similar product was the Synertek SYM-1.

One of the first external uses for the design was the Apple I microcomputer, introduced in 1976. The 6502 was next used in the Commodore PET and Apple II,[70] both released in 1977. It was later used in the Atari 8-bit computers, Acorn Atom, BBC Micro,[70] VIC-20 and other designs both for home computers and business, such as Ohio Scientific and Oric computers. The 6510, a direct successor of the 6502 with a digital I/O port and a tri-state address bus, was the CPU utilized in the best-selling[71][72] Commodore 64 home computer.

Another important use of the 6500 family was in video games. The first to make use of the processor design was the 1977 Atari VCS, later renamed the Atari 2600. The VCS used a 6502 variant named the 6507, which had fewer pins, so it could address only 8 KB of memory. Millions of the Atari consoles would be sold, each with a MOS processor. Another significant use was by the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) and Famicom. The 6502 used in the NES was a second source version by Ricoh, a partial system on a chip, that lacked the binary-coded decimal mode but added 22 memory-mapped registers and on-die hardware for sound generation, joypad reading, and sprite list DMA. Called 2A03 in NTSC consoles and 2A07 in PAL consoles,[c] this processor was produced exclusively for Nintendo.

6502 or variants were used in all of Commodore's floppy disk drives for all of their 8-bit computers, from the PET line through the Commodore 128D, including the Commodore 64. 8-inch PET drives had two 6502 processors. Atari used the same 6507 used in the Atari 2600 for its 810 and 1050 disk drives used for all of their 8-bit computer line, from the 400/800 through the XEGS.

In the 1980s, a popular electronics magazine Elektor used the processor in its microprocessor development board Junior Computer.

The CMOS successor to the 6502, the WDC 65C02, also saw use in home computers and video game consoles. Apple used it in the Apple II line starting with the Apple IIc and later variants of the Apple IIe and also offered a kit to upgrade older IIe systems with the new processor.[73] The Hudson Soft HuC6280 chip used in the TurboGrafx-16 was based on a 65C02 core. The Atari Lynx used a custom chip named "Mikey"[74] designed by Epyx which included a VLSI VL65NC02 licensed cell. The G65SC12 by GTE Microcircuits (renamed California Micro Devices) variant was used in the BBC Master. Some models of the BBC Master also included an additional G65SC102 co-processor.

- Home computers and video game consoles using the 6502 or its variants

Programmers model

[edit]

| 15 | 14 | 13 | 12 | 11 | 10 | 9 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | (bit position) |

| Main registers | ||||||||||||||||

| A | Accumulator | |||||||||||||||

| Index registers | ||||||||||||||||

| X | X index | |||||||||||||||

| Y | Y index | |||||||||||||||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | S | Stack pointer | |||||||

| Program counter | ||||||||||||||||

| PC | Program Counter | |||||||||||||||

| Status register | ||||||||||||||||

| N | V | - | B | D | I | Z | C | Processor flags | ||||||||

The 6502 is a little-endian 8-bit processor with a 16-bit address bus. The original versions were fabricated using an 8 µm[75] process technology chip with a die size of 3.9 mm × 4.3 mm (153 by 168 mils), for a total area of 16.6 mm2.[41]

The internal logic runs at the same speed as the external clock rate. It featured a simple pipeline; on each cycle, the processor fetches one byte from memory and processes another. This means that any single instruction can take as few as two cycles to complete, depending on the number of operands that instruction uses. For comparison, the Zilog Z80 required two cycles to fetch memory, and the minimum instruction time was four cycles. Thus, despite the lower clock speeds compared to competing designs, typically in the neighborhood of 1 to 2 MHz, the 6502's performance was competitive with CPUs using significantly faster clocks. This is partly due to a simple state machine implemented by combinational (clockless) logic to a greater extent than in many other designs; the two-phase clock (supplying two synchronizations per cycle) could thereby control the machine cycle directly.

This design also led to one useful design note of the 6502, and the 6800 before it. Because the chip only accessed memory during a certain part of the clock cycle, and this duration was indicated by the φ2-low clock-out pin, other chips in a system could access memory during those times when the 6502 was off the bus. This was sometimes known as "hidden access". This technique was widely used by computer systems; they would use memory capable of access at 2 MHz, and then run the CPU at 1 MHz. This guaranteed that the CPU and video hardware could interleave their accesses, with a total performance matching that of the memory device. Because this access was every other cycle, there was no need to signal the CPU to avoid using the bus, making this sort of access easy to implement without any bus logic. [76] When faster memories became available in the 1980s, newer machines could use this same technique while running at higher clock rates, the BBC Micro used newer RAM that allowed its CPU to run at 2 MHz while still using the same bus sharing techniques.

Like most simple CPUs of the era, the dynamic NMOS 6502 chip is not sequenced by microcode but decoded directly using a dedicated PLA. The decoder occupied about 15% of the chip area. This compares to later microcode-based designs like the Motorola 68000, where the microcode ROM and decoder engine represented about a third of the gates in the system.

Registers

[edit]Like its precursor, the 6800, the 6502 has very few registers. They include[77]

A= 8-bit accumulator registerP= 7-bit[78] processor status registerPC= 16-bit program counterS= 8-bit stack pointerX= 8-bit index registerY= 8-bit index register

This compares to a contemporaneous competitor, the Intel 8080, which likewise has one 8-bit accumulator and a 16-bit program counter, but has six more general-purpose 8-bit registers (which can be combined into three 16-bit pointers) and a larger 16-bit stack pointer.[80]

In order to make up somewhat for the lack of registers, the 6502 includes a zero page addressing mode that uses one address byte in the instruction instead of the two needed to address the full 64 KB of memory. This provides fast access to the first 256 bytes of RAM by using shorter instructions. For instance, an instruction to add a value from memory to the value in the accumulator would normally be three bytes, one for the instruction and two for the 16-bit address. Using the zero page reduces this to an 8-bit address, reducing the total instruction length to two bytes, and thus improving instruction performance.

The stack address space is hardwired to memory page $01, i.e. the address range $0100–$01FF (256–511). Software access to the stack is done via four implied addressing mode instructions, whose functions are to push or pop (pull) the accumulator or the processor status register. The same stack is also used for subroutine calls via the JSR (jump to subroutine) and RTS (return from subroutine) instructions and for interrupt handling.

Addressing

[edit]The chip uses the index and stack registers effectively with several addressing modes, including a fast "direct page" or "zero page" mode, similar to that found on the PDP-8, that accesses memory locations from addresses 0 to 255 with a single 8-bit address (saving the cycle normally required to fetch the high-order byte of the address)—code for the 6502 uses the zero page much as code for other processors would use registers. On some 6502-based microcomputers with an operating system, the operating system uses most of zero page, leaving only a handful of locations for the user.

Addressing modes also include implied (1-byte instructions); absolute (3 bytes); indexed absolute (3 bytes); indexed zero-page (2 bytes); relative (2 bytes); accumulator (1); indirect,x and indirect,y (2); and immediate (2). Absolute mode is a general-purpose mode. Branch instructions use a signed 8-bit offset relative to the instruction after the branch; the numerical range −128..127 therefore translates to 128 bytes backward and 127 bytes forward from the instruction following the branch (which is 126 bytes backward and 129 bytes forward from the start of the branch instruction). Accumulator mode operates on the accumulator register and does not need any operand data. Immediate mode uses an 8-bit literal operand.

Indirect addressing

[edit]The indirect modes are useful for array processing and other looping. With the 5/6 cycle "(indirect),y" mode, the 8-bit Y register is added to a 16-bit base address read from zero page, which is located by a single byte following the opcode. The Y register is therefore an index register in the sense that it is used to hold an actual index (as opposed to the X register in the 6800, where a base address was directly stored and to which an immediate offset could be added). Incrementing the index register to walk the array byte-wise takes only two additional cycles. With the less frequently used "(indirect,x)" mode the effective address for the operation is found at the zero page address formed by adding the second byte of the instruction to the contents of the X register. Using the indexed modes, the zero page effectively acts as a set of up to 128 additional (though very slow) address registers.

The 6502 is capable of performing addition and subtraction in binary or binary-coded decimal. Placing the CPU into BCD mode with the SED (set D flag) instruction results in decimal arithmetic, in which $99 + $01 would result in $00 and the carry (C) flag being set. In binary mode (CLD, clear D flag), the same operation would result in $9A and the carry flag being cleared. Other than Atari BASIC, BCD mode was seldom used in home-computer applications.

See the Hello world! article for a simple but characteristic example of 6502 assembly language.

Instructions and opcodes

[edit]6502 instruction operation codes (opcodes) are 8 bits long and have the general form AAABBBCC, where AAA and CC define the opcode, and BBB defines the addressing mode.[81] For example, the ORA instruction performs a bitwise OR on the bits in the accumulator with another value. The instruction opcode is of the form 000bbb01, where bbb may be 010 for an immediate mode value (constant), 001 for zero-page fixed address, 011 for an absolute address, and so on.[81] This pattern is not universal, as there are exceptions, but it allows opcode values to be easily converted to assembly mnemonics for the majority of instructions, handling the edge cases with special-purpose code.[81]

Of the 256 possible opcodes available using an 8-bit pattern, the original 6502 uses 151 of them, organized into 56 instructions with (possibly) multiple addressing modes. Depending on the instruction and addressing mode, the opcode may require zero, one or two additional bytes for operands. Hence 6502 machine instructions vary in length from one to three bytes.[82][83] The operand is stored in the 6502's customary little-endian format.

Each CPU machine instruction takes up a certain number of clock cycles, usually equal to the number of memory accesses. For example, the absolute indexing mode of the ORA instruction takes 4 clock cycles; 3 cycles to read the instruction and 1 cycle to read the value of the absolute address. If no memory is accessed, the number of clock cycles is two. The minimum clock cycles for any instruction is two. When using indexed addressing, if the result crosses a page boundary an extra clock cycle is added. Also, when a zero page address is used in indexing mode (e.g. zp,X) an extra clock cycle is added.

The 65C816, the 16-bit CMOS descendant of the 6502, also supports 24-bit addressing, which results in instructions being assembled with three-byte operands, also arranged in little-endian format.

The remaining 105 opcodes are undefined. In the original design, instructions where the low-order 4 bits (nibble) were 3, 7, B or F were not used, providing room for future expansion. Likewise, the $x2 column had only a single entry, LDX #constant. The remaining 25 empty slots were distributed. Some of the empty slots were used in the 65C02 to provide both new instructions and variations on existing ones with new addressing modes. The $xF instructions were initially left free to allow 3rd-party vendors to add their own instructions, but later versions of the 65C02 standardized a set of bit manipulation instructions developed by Rockwell Semiconductor.

Assembly language

[edit]A 6502 assembly language statement consists of a three-character instruction mnemonic, followed by any operands. Instructions that do not take a separate operand but target a single register based on the addressing mode combine the target register in the instruction mnemonic, so the assembler uses INX as opposed to INC X to increment the X register.

Instruction table

[edit]| Opcode matrix for the 6502 instruction set | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Addressing modes: A – accumulator, # – immediate, zpg – zero page, abs – absolute, ind – indirect, X – indexed by X register, Y – indexed by Y register, rel – relative | ||||||||||||

| High nibble | Low nibble | |||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 8 | 9 | A | C | D | E | |

| 0 | BRK | ORA (ind,X) | ORA zpg | ASL zpg | PHP | ORA # | ASL A | ORA abs | ASL abs | |||

| 1 | BPL rel | ORA (ind),Y | ORA zpg,X | ASL zpg,X | CLC | ORA abs,Y | ORA abs,X | ASL abs,X | ||||

| 2 | JSR abs | AND (ind,X) | BIT zpg | AND zpg | ROL zpg | PLP | AND # | ROL A | BIT abs | AND abs | ROL abs | |

| 3 | BMI rel | AND (ind),Y | AND zpg,X | ROL zpg,X | SEC | AND abs,Y | AND abs,X | ROL abs,X | ||||

| 4 | RTI | EOR (ind,X) | EOR zpg | LSR zpg | PHA | EOR # | LSR A | JMP abs | EOR abs | LSR abs | ||

| 5 | BVC rel | EOR (ind),Y | EOR zpg,X | LSR zpg,X | CLI | EOR abs,Y | EOR abs,X | LSR abs,X | ||||

| 6 | RTS | ADC (ind,X) | ADC zpg | ROR zpg | PLA | ADC # | ROR A | JMP (ind) | ADC abs | ROR abs | ||

| 7 | BVS rel | ADC (ind),Y | ADC zpg,X | ROR zpg,X | SEI | ADC abs,Y | ADC abs,X | ROR abs,X | ||||

| 8 | STA (ind,X) | STY zpg | STA zpg | STX zpg | DEY | TXA | STY abs | STA abs | STX abs | |||

| 9 | BCC rel | STA (ind),Y | STY zpg,X | STA zpg,X | STX zpg,Y | TYA | STA abs,Y | TXS | STA abs,X | |||

| A | LDY # | LDA (ind,X) | LDX # | LDY zpg | LDA zpg | LDX zpg | TAY | LDA # | TAX | LDY abs | LDA abs | LDX abs |

| B | BCS rel | LDA (ind),Y | LDY zpg,X | LDA zpg,X | LDX zpg,Y | CLV | LDA abs,Y | TSX | LDY abs,X | LDA abs,X | LDX abs,Y | |

| C | CPY # | CMP (ind,X) | CPY zpg | CMP zpg | DEC zpg | INY | CMP # | DEX | CPY abs | CMP abs | DEC abs | |

| D | BNE rel | CMP (ind),Y | CMP zpg,X | DEC zpg,X | CLD | CMP abs,Y | CMP abs,X | DEC abs,X | ||||

| E | CPX # | SBC (ind,X) | CPX zpg | SBC zpg | INC zpg | INX | SBC # | NOP | CPX abs | SBC abs | INC abs | |

| F | BEQ rel | SBC (ind),Y | SBC zpg,X | INC zpg,X | SED | SBC abs,Y | SBC abs,X | INC abs,X | ||||

| Blank opcodes (e.g., F2) and all opcodes whose low nibbles are 3, 7, B and F are undefined in the 6502 instruction set. | ||||||||||||

Example code

[edit]The following 6502 assembly language source code is for a subroutine named TOLOWER, which copies a null-terminated character string from one location to another, converting upper-case letter characters to lower-case letters. The string being copied is the "source", and the string into which the converted source is stored is the "destination".

0080 0080 00 04 0082 00 05 0600 0600 A0 00 0602 B1 80 0604 F0 11 0606 C9 41 0608 90 06 060A C9 5B 060C B0 02 060E 09 20 0610 91 82 0612 C8 0613 D0 ED 0615 38 0616 60 0617 91 82 0619 18 061A 60 061B |

; TOLOWER:

;

; Convert a null-terminated character string to all lower case.

; Maximum string length is 255 characters, plus the null term-

; inator.

;

; Parameters:

;

; SRC – Source string address

; DST – Destination string address

;

ORG $0080

;

SRC .WORD $0400 ;source string pointer

DST .WORD $0500 ;destination string pointer

;

ORG $0600 ;execution start address

;

TOLOWER LDY #$00 ;starting index

;

LOOP LDA (SRC),Y ;get from source string

BEQ DONE ;end of string

;

CMP #'A' ;if lower than UC alphabet...

BCC SKIP ;copy unchanged

;

CMP #'Z'+1 ;if greater than UC alphabet...

BCS SKIP ;copy unchanged

;

ORA #%00100000 ;convert to lower case

;

SKIP STA (DST),Y ;store to destination string

INY ;bump index

BNE LOOP ;next character

;

; NOTE: If Y wraps the destination string will be left in an undefined

; state. We set carry to indicate this to the calling function.

;

SEC ;report string too long error &...

RTS ;return to caller

;

DONE STA (DST),Y ;terminate destination string

CLC ;report conversion completed &...

RTS ;return to caller

;

.END

|

IC hardware design

[edit]

The processor's non-maskable interrupt (NMI) input is edge sensitive, which means that the interrupt is triggered by the falling edge of the signal rather than its level. Consequently a wired-OR interrupt circuit cannot be readily supported. However, this also prevents nested NMI interrupts from occurring until the interrupt source hardware makes the NMI input inactive again, often under control of the NMI interrupt handler.

The simultaneous assertion of the NMI and IRQ (maskable) hardware interrupt lines causes IRQ to be ignored. However, if the IRQ line remains asserted after the servicing of the NMI, the processor will almost immediately respond to IRQ, as IRQ is level sensitive. Thus a sort of built-in interrupt priority was established in the 6502 design. (The first opcode of the NMI handler is executed before the IRQ is detected again.)

The B flag is set by the 6502's periodically sampling its NMI edge detector's output and its IRQ input. The IRQ signal being driven low is only recognized though if IRQs are not masked by the I flag. If in this way a NMI request or (maskable) IRQ is detected the B flag is set to zero and causes the processor to execute the BRK instruction next instead of executing the next instruction based on the program counter.[84][85]

The BRK instruction then pushes the processor status onto the stack, with the B flag bit set to zero. At the end of its execution the BRK instruction resets the B flag's value to one. This is the only way the B flag can be modified. If an instruction other than the BRK instruction pushes the B flag onto the stack as part of the processor status[86] the B flag always has the value one.

A high-to-low transition on the SO input pin will set the processor's overflow status bit. This can be used for fast response to external hardware. For example, a high-speed polling device driver can poll the hardware once in only three cycles using a Branch-on-oVerflow-Clear (BVC) instruction that branches to itself until overflow is set by an SO falling transition. The Commodore 1541 and other Commodore floppy disk drives use this technique to detect when the serializer is ready to transfer another byte of disk data. The system hardware and software design must ensure that an SO will not occur during arithmetic processing and disrupt calculations.

Variations and derivatives

[edit]The 6502 was the most prolific variant of the 65xx series family from MOS Technology.

The 6501 and 6502 have 40-pin DIP packages; the 6503, 6504, 6505, and 6507 are 28-pin DIP versions, for reduced chip and circuit board cost. In all of the 28-pin versions, the pin count is reduced by leaving off some of the high-order address pins and various combinations of function pins, making those functions unavailable.

| Pin | 6800 | 6501 | 6502 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | Halt | Ready | Ready |

| 3 | ∅1 (in) | ∅1 (in) | ∅1 (out) |

| 5 | Valid memory address | Valid memory address | N.C. |

| 7 | Bus available | Bus available | SYNC |

| 36 | Data bus enable | Data bus enable | N.C. |

| 37 | ∅2 (in) | ∅2 (in) | ∅0 (in) |

| 38 | N.C. | N.C. | Set overflow flag |

| 39 | Three-state control | N.C. | ∅2 (out) |

Typically, the 12 pins omitted to reduce the pin count from 40 to 28 are the three not connected (NC) pins, one of the two Vss pins, one of the clock pins, the SYNC pin, the set overflow (SO) pin, either the maskable interrupt or the non-maskable interrupt (NMI), and the four most-significant address lines (A12–A15). The omission of four address pins reduces the external addressability to 4 KB (from the 64 KB of the 6502), though the internal PC register and all effective address calculations remain 16-bit.

The 6507 omits both interrupt pins in order to include address line A12, providing 8 KB of external addressability but no interrupt capability. The 6507 was used in the popular Atari 2600 video game console, the design of which divides the 8 KB memory space in half, allocating the lower half to the console's internal RAM and peripherals, and the upper half to the Game Cartridge, so Atari 2600 cartridges have a 4 KB address limit (and the same capacity limit unless the cartridge contains bank switching circuitry).

One popular 6502-based computer, the Commodore 64, used a modified 6502 CPU, the 6510. Unlike the 6503–6505 and 6507, the 6510 is a 40-pin chip that adds internal hardware: a 6-bit parallel I/O port mapped to addresses 0000 and 0001. The 6508 is another chip that, like the 6510, adds internal hardware: 256 bytes of SRAM and an 8-bit I/O port similar to those featured by the 6510. Though these chips do not have reduced pin counts compared to the 6502, they need new pins for the added parallel I/O port. In this case, no address lines are among the removed pins.

| Company | Model | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 6502 | A 1 MHz chip used in KIM-1 and other single board computers in the mid-1970s. | |

| 6502A | A 1.5 MHz chip used in Asteroids Deluxe and at 2 MHz in the BBC Micro | |

| 6502B | Version of the 6502 capable of running at a maximum speed of 3 MHz instead of 2 MHz. The B was used in both the Apple III and early Atari 8-bit computers, each running at ~1.8 MHz.[d] | |

| 6502C | The “official” 6502C was a version of the original 6502 able to run at up to 4 MHz.

Not to be confused with SALLY, a custom 6502 designed for Atari (and sometimes referred to by them as "6502C"[87]) nor with the similarly named 65C02. | |

| SALLY, C014806, "6502C" | Custom 6502 variant designed for Atari, used in later Atari 8-bit computers and Atari 5200 and Atari 7800 consoles.

Has a HALT signal on pin 35 and the R/W signal on pin 36 (these pins are not connected (N/C) on a standard 6502). Pulling HALT low latches the clock, pausing the processor. This was used to allow the video circuitry direct memory access (DMA).[88] Although sometimes referred to as "6502C" in Atari documentation, this is not the same as the official 6502C and the chip itself is never marked as such.[87] | |

| MOS | 6503 | Reduced memory addressing capability (4 KB) and no RDY input, in a 28-pin DIP package (with the phase 1 (OUT), SYNC, redundant Vss, and SO pins of the 6502 also omitted).[89] |

| MOS | 6504 | Reduced memory addressing capability (8 KB), no NMI, and no RDY input, in a 28-pin DIP package (with the phase 1 (OUT), SYNC, redundant Vss, and SO pins of the 6502 also omitted).[89] |

| MOS | 6505 | Reduced memory addressing capability (4 KB) and no NMI, in a 28-pin DIP package (with the phase 1 (OUT), SYNC, redundant Vss, and SO pins of the 6502 also omitted).[89] |

| MOS | 6506 | Reduced memory addressing capability (4 KB), no NMI, and no RDY input, but all 3 clock pins of the 6502 (i.e. a 2-phase output clock), in a 28-pin DIP package (with the SYNC, redundant Vss, and SO pins of the 6502 also omitted).[89] |

| MOS | 6507 | Reduced memory addressing capability (8 KB) and no interrupts, in a 28-pin DIP package (with the phase 1 (OUT), SYNC, redundant Vss, and SO pins of the 6502 also omitted).[89] This chip was used in the Atari 2600 video game system and in many Atari 8-bit computer peripherals. |

| MOS | 6508 | Has a built-in 8-bit input/output port and 256 bytes of internal static RAM. |

| MOS | 6509 | Can address up to 1 MB of RAM as 16 banks of 64 KB and was used in the Commodore CBM-II series. |

| MOS | 6510 | Has a built-in 6-bit programmable input/output port and was used in the Commodore 64. The 8500 is effectively an HMOS version of the 6510, and replaced it in later versions of the C64. |

| MOS | 6512 6513 6514 6515 |

The MOS Technology 6512, 6513, 6514, and 6515 each rely on an external clock, instead of using an internal clock generator like the 650x (e.g. 6502). This was used to advantage in some designs where the clocks could be run asymmetrically, increasing overall CPU performance.

The 6512 is a 6502 with a 2-phase clock input for an external clock oscillator, instead of an on-board clock oscillator.[89] The 6513, 6514 and 6515 are similarly equivalent to (respectively) a 6503, 6504 and 6505 with the same 2-phase clock input.[89] The 6512 was used in the BBC Micro B+64. |

| Ricoh | RP2A03 RP2A07 |

Unlicensed 6502 variants running at ~1.8 MHz[d] including an audio processing unit but lacking the BCD mode, used in the Nintendo Entertainment System. |

| MOS | 6591 6592 |

System on a chip designs that utilize a complete Atari 2600 in a 48-pin DIP package.[90][91] |

| WDC | 65C02 | CMOS version of the NMOS 6502 that was designed by Bill Mensch of the Western Design Center (WDC), featuring reduced power consumption, support for much higher clock speeds, new instructions, new addressing modes for some existing instructions, and correction of NMOS errata, such as the JMP ($xxFF) bug.

|

| CSG, MOS | 65CE02 | CMOS variant developed by the Commodore Semiconductor Group (CSG), formerly MOS Technology. The 65CE02 provides a further enhanced instruction set from the 65C02, featuring a third indexing register (Z), base page register, 16-bit stack and faster program execution with the minimal instruction timing reduced from 2 to 1 clock cycles. |

| Rockwell | R6511Q R6500/11, R6500/12, R6500/15 "One-Chip Microcomputers" |

Enhanced versions of the 6502-based processor, also including individual bit manipulation operations (RMB, SMB, BBR and BBS), on-chip 192-byte zero-page RAM, UART, etc.[92][93] |

| Rockwell | R65F11 R65F12 |

The Rockwell R65F11 (introduced in 1983) and the later R65F12 are enhanced versions of the 6502-based processor, also including individual bit manipulation operations (RMB, SMB, BBR and BBS), on-chip zero-page RAM, on-chip Forth kernel ROM, a UART, etc.[94][95][96][97][98] |

| GTE | G65SC12 | Drop in 6502 CMOS variant without individual bit manipulation operations (RMB, SMB, BBR and BBS).[99] This was used in the BBC Master. |

| GTE | G65SC102 | Software compatible with the 6502, but has a slightly different pinout and oscillator circuit. The BBC Master Turbo included the 4 MHz version of this CPU on a coprocessor card, which could also be bought separately and added to the Master 128. |

| Rockwell | R65C00 R65C21 R65C29 |

The R65C00, R65C21, and R65C29 have two enhanced CMOS 6502s in a single chip, and the R65C00 and R65C21 additionally contained 2 KB of mask-programmable ROM.[100][101] |

| CM630 | A 1 MHz Eastern Bloc clone of the 6502 and was used in the Pravetz 8A and 8C, Bulgarian clones of the Apple II.[102] | |

| MOS | 7501 8501 |

6510 (an enhanced 6502) variants, introduced in 1984.[103] They extended the number of I/O port pins from 6 to 7, but omitted pins for non-maskable interrupt and clock output.[104] Used in Commodore's C-16, C-116 and Plus/4 computers. The main difference between 7501 and 8501 CPUs is that the 7501 was manufactured with the HMOS-1 process and the 8501 with HMOS-2.[103] |

| MOS | 8500 | Introduced in 1985 as an HMOS version of the 6510 (which is in turn based on the 6502). Other than the process modification, the 8500 is virtually identical to the NMOS version of the 6510. It replaced the 6510 in later versions of the Commodore 64. |

| MOS | 8502 | Designed by MOS Technology and used in the Commodore 128. Based on the MOS 6510 used in the Commodore 64, the 8502 was able run at double clock rate of the 6510.[105] The 8502 family also includes the MOS 7501, 8500 and 8501. |

| Hudson Soft | HuC6280 | Japanese video game company Hudson Soft's improved version of the WDC 65C02. Manufactured for them by Seiko Epson and NEC for the SuperGrafx. The most notable product using the HuC6280 is NEC's TurboGrafx-16 video game console. |

| VLSI | VL65NC02[106] | VLSI licensed 65C02 variant was included in the Atari Lynx's main system IC named Mikey. |

16-bit derivatives

[edit]The Western Design Center designed and, as of 2025[update], still produces the WDC 65C816S processor, a 16-bit, static-core successor to the 65C02. The W65C816S is a newer variant of the 65C816, which is the core of the Apple IIGS computer and is the basis of the Ricoh 5A22 processor that powers the Super Nintendo Entertainment System. The W65C816S incorporates minor improvements over the 65C816 that make the newer chip not an exact hardware-compatible replacement for the earlier one. Among these improvements was conversion to a static core, which makes it possible to stop the clock in either phase without the registers losing data. Available through electronics distributors, as of March 2020, the W65C816S is officially rated for 14 MHz operation.

The Western Design Center also designed and produced the 65C802, which was a 65C816 core with a 64-kilobyte address space in a 65(C)02 pin-compatible package. The 65C802 could be retrofitted to a 6502 board and would function as a 65C02 on power-up, operating in "emulation mode." As with the 65C816, a two-instruction sequence would switch the 65C802 to "native mode" operation, exposing its 16-bit accumulator and index registers, and other 65C816 features. The 65C802 was not widely used and production ended.

Bugs and quirks

[edit]The 6502 had several bugs and quirks, which had to be accounted for when programming it:

- The earliest revisions of the 6502, such as those shipped with some KIM-1 computers, did not have a ROR (rotate right memory or accumulator) instruction. In these chips, the operation of the opcode that was later assigned to ROR is effectively an ASL (arithmetic shift left) instruction that does not affect the carry bit in the status register. Initially, MOS intentionally excluded ROR from the instruction set, deeming it not of enough value to justify its costs. In reaction to many customer inquiries, MOS promised in the second edition of the MCS6500 Programming Manual (document no. 6500-50A) that ROR would appear in 6502 chips starting in 1976.[51][e] The vast majority of 6502 chips in existence today do feature the ROR instruction; these include all those CPUs originally installed in popular fully-assembled microcomputers such as the Apple II and Commodore 64 lines, all of which were manufactured after 1976.

- The NMOS 6502 family has a variety of undocumented instructions, which vary from one chip manufacturer to another. The 6502 instruction decoding is implemented in a hardwired logic array (similar to a programmable logic array) that is only defined for 151 of the 256 available opcodes. The remaining 105 trigger strange and occasionally hard-to-predict actions, such as crashing the processor, performing two valid instructions consecutively, performing strange mixtures of two instructions, or simply doing nothing at all. Some hardware designers used the undefined opcodes to extend the 6502 instruction set by detecting when a certain undefined opcode is fetched and performing an extension operation externally to the processor while substituting a neutral (NOP-like) opcode to the 6502 in order to make it idle while the external hardware handles the extension operation. Also, some programmers utilized this feature to extend the 6502 instruction set by providing functionality for the unimplemented opcodes with specially written software intercepted at the BRK instruction's 0xFFFE vector.[107][108] All of the undefined opcodes have been replaced with NOP instructions in the 65C02, an enhanced CMOS version of the 6502, although with varying byte sizes and execution times. (Some of them actually perform memory read operations but then ignore the data.) In the 65C802/65C816, all 256 opcodes perform defined operations.

- The 6502's memory indirect jump instruction,

JMP (<address>), has a nonintuitive limitation which many users consider a defect. If <address> is hex xxFF (i.e., any word ending in FF), the processor will not jump to the address stored in xxFF andxxFF+1as expected, but rather the one defined by xxFF and xx00 (for example,JMP ($10FF)would jump to the address stored in 10FF and 1000, instead of the one stored in 10FF and 1100). This can be avoided simply by not placing any indirect jump target address across a page boundary, and the MOS Technology MCS6500 Programming Manual gives reason to believe that this was the intention of the designers of the 6502, in order to save space on the chip that would have been used to implement the more complex behavior of conditionally adding 1 clock cycle to propagate the carry when necessary. This ostensible defect continued through the entire NMOS line but was corrected in the CMOS derivatives. - The NMOS 6502 indexed addressing across page boundaries will do an extra read of an invalid address in the page of the base address (to which the index is added). This characteristic may cause random issues by accessing hardware that acts on a read, such as clearing timer or IRQ flags, sending an I/O handshake, etc. The extra read can be predicted and managed to avoid such problems, but only with special care in both hardware and software design. This flaw continued through the entire NMOS line but was corrected in the CMOS derivatives, in which the processor does an extra read of the last instruction byte.

- The 6502 read–modify–write instructions perform one read and two write cycles. First, the unmodified data that was read is written back, and then the modified data is written. This characteristic may cause issues by twice accessing hardware that acts on a write. This anomaly continued through the full NMOS line but was fixed in the CMOS derivatives, in which the processor does two reads and one write cycle. Defensive programming practice will generally avoid this problem by not executing read/modify/write instructions on hardware registers.

- The N (result negative), V (sign bit overflow) and Z (result zero) status flags are generally meaningless when performing arithmetic operations while the processor is in BCD mode, as these flags are undefined in decimal mode and have been empirically shown to reflect the binary, not BCD, result. This limitation was removed in the CMOS derivatives, at the cost of one added clock cycle for an ADC or SBC instruction in decimal mode (except on the 65C816). Therefore, this feature may be used to distinguish a CMOS processor from an NMOS version (by relying on the undocumented behavior of the NMOS version).[109]

- If the 6502 happens to be in BCD mode when a hardware interrupt occurs, it will not revert to binary mode. This characteristic could result in obscure bugs in the interrupt service routine (ISR) if it fails to clear BCD mode before performing any arithmetic operations. The 6502 programming manual thus requires each ISR to reset or set the D flag if it uses the ADC or SBC instruction, but occasionally a human programmer may mistakenly omit to do this, causing a bug. For example, the Commodore 64's KERNAL did not correctly handle this processor characteristic, requiring that IRQs be disabled or re-vectored during BCD math operations. This issue was addressed in the CMOS derivatives also, by making reset and all interrupts automatically reset the D flag. (The change has the one disadvantage that it makes a [rare] program that operates continuously in decimal mode slightly longer and slower, as now every ISR must set the D flag before executing ADC or SBC.)

- The 6502 instruction set includes BRK (opcode $00), which is technically a software interrupt (similar in spirit to the SWI mnemonic of the Motorola 6800 and ARM processors). BRK is most often used to interrupt program execution and start a machine language monitor for testing and debugging during software development. BRK could also be used to route program execution using a simple jump table (analogous to the manner in which the Intel 8086 and derivatives handle software interrupts by number). However, if a maskable hardware interrupt occurs when the processor is fetching a BRK instruction, the NMOS version of the processor will fail to execute BRK and instead proceed as if only the hardware interrupt had occurred. This fault—an unequivocal hardware bug—was corrected in the CMOS implementation of the processor, which first calls the ISR for the hardware interrupt and then executes the BRK instruction.

- When executing JSR (jump to subroutine) and RTS (return from subroutine) instructions, the return address pushed to the stack by JSR is that of the last byte of the JSR operand (that is, the most significant byte of the subroutine address), rather than the address of the following instruction. This is because the actual copy (from program counter to stack and then conversely) takes place before the automatic increment of the program counter that occurs at the end of every instruction.[110] This characteristic would go unnoticed unless the code examined the return address in order to retrieve parameters in the code stream (a 6502 programming idiom documented in the ProDOS 8 Technical Reference Manual). It remains a characteristic of 6502 derivatives to this day. The original MCS6500 Programming Manual points it out and explains the reason: it saves one clock cycle in the JSR by not incrementing the PC before pushing it, while in the RET instruction, the deferred increment of the pulled PC is overlapped with other steps and adds no clock cycle. As designed, a JSR and RET take 12 clock cycles total; if the JSR pushed the incremented PC, the call and return would take 13 clock cycles.

- The SBC instruction (Subtract Memory from Accumulator with Borrow) uses inverted carry as borrow. A zero carry flag is used to signal borrow from previous subtract. If a borrow is not desired, the carry bit must be set before the SBC instruction. This way the ALU subtract logic can reuse the add logic with just inverted second input which saves a lot of gates.

- The read access of the CPU can be delayed by setting the RDY pin to low temporarily. However, during write access, which can take up to three consecutive clock cycles for a BRK instruction, the CPU will stop only in the next read cycle.[111] This quirk was corrected in the CMOS derivatives and also in the 6510 and its variants.

See also

[edit]- List of 6502 assemblers

- MOS Technology 6502-based home computers

- Transistor count

- Apple II accelerators

- cc65 – 6502 macro assembler and C compiler

Notes

[edit]- ^ One example of such a design was the Atari 8-bit computers, which use DMA to share memory between the 6502 and the ANTIC video chip. This was implemented with a single flip-flop, which was later built into custom Sally versions of the 6502 used in these machines. The flip flop enabled a pair of 74LS244 bus drivers that could isolate the 6502's address bus when DMA was required.[48]

- ^ Since the OP code still did something in the original version of the processor, just not a correct ROR instruction, this caused a persistent myth that the original 6502 had a bug in its ROR instruction.[52][53][54]

- ^ The difference between the parts being the clock frequency divider ratio and a lookup table for audio sample rates.

- ^ a b More precisely these systems internally divide an NTSC colorburst crystal yielding 315⁄176 Mhz = 1.7897727 MHz

- ^ Eric Schlaepfer, who built a transistorized replica of the 6502 at monster6502.com, argues in his Youtube video "The 6502 Rotate Right Myth" (by TubeTimeUS) that according to Chuck Peddle and Bill Mensch there was no ROR bug. Instead, the instruction was not implemented at all as it was deemed unnecessary. Schlaepfer then compares screenshots from the early revision to later revisions of the 6502 and proves that the ROR instruction was not present in either the instruction decoding, wiring, or execution parts of the chip.

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ "The MOS 6502 and the Best Layout Guy in the World". swtch.com. 2011-01-03. Archived from the original on 2014-09-08. Retrieved 2014-08-09.

- ^ "MOnSter6502 A complete, working discrete transistors (i.e. not integrated all on a single chip) replica of the classic MOS 6502 microprocessor". monster6502.com. 2017. Archived from the original on 2017-05-12. Retrieved 2017-05-01.

- ^ a b William Mensch (October 9, 1995). "Interview with William Mensch" (Web video). Interviewed by Rob Walker. Atherton, California: Silicon Genesis Project, Stanford University Libraries. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved December 22, 2023. William Mensch and the moderator both pronounce the 6502 microprocessor as "sixty-five-oh-two".

- ^ "Western Design Center (WDC) Home of 65xx Microprocessor Technology". www.westerndesigncenter.com. Archived from the original on 2019-04-08. Retrieved 2019-04-08.

- ^ Guston, David H. (2010). Encyclopedia of Nanoscience and Society. Sage Publications. p. 272. ISBN 9781452266176. Archived from the original on January 20, 2021. Retrieved May 5, 2017.

- ^ "Chuck Peddle Byte Interview" (PDF). Byte.

- ^ a b LowSpecGamer (April 29, 2022). The First LowSpec Processor. YouTube. Retrieved March 5, 2025.

- ^ Jenkins, Francis; Lane, E.; Lattin, W.; Richardson, W. (November 1973). "MOS-device modeling for computer implementation". IEEE Transactions on Circuit Theory. 20 (6). IEEE: 649–658. doi:10.1109/tct.1973.1083758. ISSN 0018-9324. All of the authors were with Motorola's Semiconductor Products Division.

- ^ "Motorola joins microprocessor race with 8-bit entry". Electronics. 47 (5). New York: McGraw-Hill: 29–30. March 7, 1974.

- ^ Motorola 6800 Oral History (2008), p. 9

- ^ US3942047A, Buchanan, John K., "MOS DC Voltage booster circuit", issued 1976-03-02 Archived 2024-02-13 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ US3987418A, Buchanan, John K., "Chip topography for MOS integrated circuitry microprocessor chip", issued 1976-10-19 Archived 2024-02-13 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Motorola 6800 Oral History (2008), p. 8

- ^ Mensch Oral History (1995) Mensch earned an Associate degree from Temple University in 1966 and then worked at Philco Ford as an electronics technician before attending the University of Arizona.

- ^ US3968478A, Jr, William D. Mensch, "Chip topography for MOS interface circuit", issued 1976-07-06 Archived 2024-02-13 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Donohue, James F. (October 27, 1988). "The microprocessor first two decades: The way it was". EDN. 33 (22A). Cahners Publishing: 18–32. ISSN 0012-7515. Page 30. Bennett already was at work on what became the 6800. "He hired me," Peddle says of Bennett, "to do the architectural support work for the product he'd already started." … Peddle says. "Motorola tried to kill it several times. Without Bennett, the 6800 would not have happened, and a lot of the industry would not have happened, either."

- ^ US3975712A, Hepworth, Edward C.; Means, Rodney J. & Peddle, Charles I., "Asynchronous communication interface adaptor", issued 1976-08-17 Archived 2024-02-13 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Motorola (August 5, 1976). "They stay out front with Motorola's M6800 Family". Electronics. 49 (16). McGraw-Hill: 51. Archived from the original on January 10, 2014. Retrieved June 4, 2012. Advertisement showing three embedded applications from TRW, HP and RUSCO.

- ^ Motorola 6800 Oral History (2008), p. 89

- ^ "It's the total product family". Electronics. 48 (1). New York: McGraw Hill: 37. January 9, 1975. Archived from the original on November 11, 2012. Retrieved June 4, 2012. Motorola advertisement emphasizing their complete set of peripheral chips and development tools. This shortened the customer's product design cycle.

- ^ Motorola 6800 Oral History (2008) p. 18

- ^ "Motorola microprocessor set is 1 MHz n-MOS". Control Engineering. 21 (11): 11. November 1974. MC6800 microprocessor price was $360. The MC6850 asynchronous communications interface adaptor (ACIA) was slated for first quarter 1975 introduction.

- ^ Kaye, Glynnis Thompson, ed. (1984). A Revolution in Progress: A History to Date of Intel (PDF). Intel Corporation. p. 14. Order number:231295. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 October 2012. Retrieved 30 December 2016. "Shima implemented the 8080 in about a year and the new device was introduced in April 1974 for $360."

- ^ "Motorola mounts M6800 drive". Electronics. 48 (8). New York: McGraw-Hill: 25. April 17, 1975. "Distributors are being stocked with the M6800 family, and the division is also offering an introductory kit that includes the family's six initial parts, plus applications and programming manuals, for $300."

- ^ Interview 2014, 52:30.

- ^ Interview 2014, 54:45.

- ^ Bagnall (2010), p. 11. Peddle's new offer came at an opportune time for the 6800 developers. "They didn't want to go to Austin, Texas," explains Mensch.

- ^ Interview 2014, 54:40.

- ^ Interview 2014, 55:50.

- ^ "Motorola Sues MOS Technology" (PDF). Microcomputer Digest. 2 (6). Cupertino CA: Microcomputer Associates: 11. December 1975. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 4, 2009.

- ^ Waller, Larry (November 13, 1975). "Motorola seeks to end skid". Electronics. 48 (23). New York: McGraw-Hill: 96–98. Summary: Semiconductor Products split into two parts, integrated circuits and discrete components. Semiconductor losses for the last four quarters exceeded $30 million. The sales organization lost its sensitivity to customer needs, "delays in responding to price cuts meant that customers bought elsewhere." Technical problems plagued IC production. The troubles are "not in design, but in chip and die yields." Problems have been solved. The MC6800 microprocessor "arrived in November 1974."

- ^ Interview 2014, 56:30.

- ^ Interview 2014, 55:00.

- ^ Bagnall (2010), p. 13.

- ^ MOS Technology (November 14, 1974). "The First Single Chip Scientific Calculator Arrays". Electronics. 47 (23). McGraw-Hill: 90–91. Archived from the original on January 10, 2014. Retrieved June 4, 2012.

- ^ Interview 2014, 57:00.

- ^ Interview 2014, 58:30.

- ^ Cass, Stephen (16 September 2021). "Q&A With Co-Creator of the 6502 Processor". IEEE Spectrum. Archived from the original on 20 September 2021. Retrieved 20 September 2021.

- ^ Ho, Joshua (9 October 2014). "An Introduction to Semiconductor Physics, Technology, and Industry". Anandtech. Archived from the original on 24 February 2020. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- ^ Motorola 6800 Oral History (2008), p. 10.

- ^ a b c Cushman 1975, p. 40.

- ^ "8080A microprocessor – DIP 40 package". CPU World. Archived from the original on 2020-09-15. Retrieved 2020-02-24.

- ^ a b Cushman 1975, p. 38.

- ^ a b "Moore's Law Milestones". IEEE. 30 April 2015. Archived from the original on 2020-02-24. Retrieved 2020-02-24.

- ^ Bagnall (2010), p. 19: "Paivinen promised Peddle he would have the n-channel process ready. He was true to his word."

- ^ a b c Cushman 1975, p. 36.

- ^ a b c Cushman 1975, p. 41.

- ^ Purcaru, John (2014). Games vs. Hardware. The History of PC video games: The 80's. p. 317.

- ^ Interview 2014, 1:01:00.

- ^ Interview 2014, 1:02:00.

- ^ a b File:MCS650x Instruction Set.jpg

- ^ "Measuring the ROR Bug in the Early MOS 6502". pagetable.com. Archived from the original on 2023-03-21. Retrieved 2023-02-25.

- ^ "How to test a ceramic 6502 for the ROR bug? | Applefritter". Archived from the original on 2023-02-25. Retrieved 2023-02-25.

- ^ "The 6502 Rotate Right Myth". YouTube. 21 February 2023. Archived from the original on 2023-02-25. Retrieved 2023-02-25.

- ^ "Microprocessor line offers 4, 8, 16 bits". Electronics. 48 (15). New York: McGraw-Hill: 118. July 24, 1975. The article covers the 6501 and 6502 plus the 28-pin versions that would only address 4K of memory. It also covered future devices such as "a design that Peddle calls a pseudo 16".

- ^ Sugarman, Robert (25 August 1975). "Does the Country Need A Good $20 Microprocessor?" (PDF). EE Times. Manhasset, New York: CMP Publications: 25. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 February 2007. Retrieved 5 February 2008.

- ^ Fylstra, Daniel (November 1975). "Son of Motorola (or the $20 CPU Chip)". Byte. 1 (3). Peterborough, NH: Green Publishing: 56–62. Comparison of the 6502 and the 6800 microprocessors. Author visited MOS Technology in August 1975.

- ^ "3rd Generation Microprocessor" (PDF). Microcomputer Digest. 2 (2). Cupertino, CA: Microcomputer Associates: 1–3. August 1975. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-07-04. Retrieved 2009-11-27.

- ^ "MOS 6501 Microprocessor beats 'em all". Electronics. 48 (16). New York: McGraw-Hill: 60–61. August 7, 1975.

- ^ "MOS 6502 the second of a low cost high performance microprocessor family". Computer. 8 (9). IEEE Computer Society: 38–39. September 1975. doi:10.1109/C-M.1975.219074. Archived from the original on 2021-02-24. Retrieved 2012-06-04.

- ^ Bagnall (2010), pp. 33–35.

- ^ Signetics (October 30, 1975). "Easiest-to-use microprocessor". Electronics. 48 (22). McGraw-Hill: 114–115. Archived from the original on November 20, 2015. Retrieved November 20, 2015.

- ^ Motorola (October 30, 1975). "All this and unbundled $69 microprocessor". Electronics. 48 (22). McGraw-Hill: 11. Archived from the original on December 15, 2011. Retrieved August 8, 2010. The quantity one price for the MC6800 was reduced from $175 to $69. The previous price for 50 to 99 units was $125.

- ^ Waller, Larry (November 13, 1975). "News briefs: Motorola seeks to stop microprocessor foe". Electronics. 48 (23). New York: McGraw-Hill: 38."Motorola said last week it would seek an immediate injunction to stop MOS Technology Inc., Norristown, Pa., from making and selling microprocessor products, including its MCS6500." (This issue was published on November 7.)

- ^ Motorola was awarded the following US Patents on the 6800 microprocessor family: U.S. patent 3,962,682, U.S. patent 3,968,478, U.S. patent 3,975,712, U.S. patent 3,979,730, U.S. patent 3,979,732, U.S. patent 3,987,418, U.S. patent 4,003,028, U.S. patent 4,004,281, U.S. patent 4,004,283, U.S. patent 4,006,457, U.S. patent 4,010,448, U.S. patent 4,016,546, U.S. patent 4,020,472, U.S. patent 4,030,079, U.S. patent 4,032,896, U.S. patent 4,037,204, U.S. patent 4,040,035, U.S. patent 4,069,510, U.S. patent 4,071,887, U.S. patent 4,086,627, U.S. patent 4,087,855, U.S. patent 4,090,236, U.S. patent 4,145,751, U.S. patent 4,218,740, U.S. patent 4,263,650.

- ^ Bagnall (2010), p. 53–54. "He [Mike Janes] had all his original work from the 6800 and hid it from Motorola…"

- ^ "Motorola, MOS Technology settle patent suit". Electronics. 49 (7). New York: McGraw-Hill: 39. April 1, 1975. "MOS Technology Inc. of Norristown, Pa. has agreed to withdraw its MCS6501 microprocessor from the market and to pay Motorola Inc. $200,000 ..." "MOS Technology and eight former Motorola employees have given back, under court order documents that Motorola contends are confidential." "…both companies have agreed to a cross license relating to patents in the microprocessor field."

- ^ Bagnall (2010), pp. 55-56

- ^ "Mergers and Acquisitions". Mini-Micro Systems. 9 (11). Cahners: 19. November 1976." Commodore International … is buying MOS Technology (Norristown, PA). This saves the six-year-old semiconductor house from impending disaster."

- ^ a b Goodwins, Rupert (December 4, 2010). "Intel's victims: Eight would-be giant killers". ZDNet. Archived from the original on May 5, 2013. Retrieved March 7, 2012.

- ^ Reimer, Jeremy. "Personal Computer Market Share: 1975-2004". Archived from the original on 6 June 2012. Retrieved 2009-07-17.

- ^ "How many Commodore 64 computers were sold?". Archived from the original on 2016-03-06. Retrieved 2011-02-01.

- ^ "Apple IIe Enhancement Kit - Peripheral - Computing History". www.computinghistory.org.uk. Archived from the original on 2020-08-08. Retrieved 2023-10-23.

- ^ "4. CPU/ROM". www.monlynx.de. Archived from the original on 2023-09-20. Retrieved 2023-10-23.

- ^ Corder, Mike (Spring 1999). "Big Things in Small Packages". Pioneers' Progress with picoJava Technology. Sun Microelectronics. Archived from the original on 2006-03-12. Retrieved April 23, 2012.

The first 6502 was fabricated with 8 micron technology, ran at one megahertz and had a maximum memory of 64k.

- ^ "How to implement bus sharing / DMA on a 6502 system". Archived from the original on 2020-08-15. Retrieved 2020-09-30.

- ^ "PROGRAMMING MODEL MCS650X". MOS MICROCOMPUTERS PROGRAMMING MANUAL. MOS TECHNOLOGY, INC. January 1976.

- ^ Anderson, J.S. (2012-08-21). Microprocessor Technology. Routledge. p. 153. ISBN 9781136078057.

- ^ "Status flags". NESdev Wiki. Retrieved 2024-06-11.

- ^ "8080A/8080A-1/8080A-2 8-Bit N Channel Microprocessor" (PDF). Intel. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 15, 2021. Retrieved November 16, 2021.

- ^ a b c Parker, Neil. "The 6502/65C02/65C816 Instruction Set Decoded". Neil Parker's Apple II page. Archived from the original on 2019-07-16. Retrieved 2019-07-16.

- ^ 6502 Instruction Set Archived 2018-05-08 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ NMOS 6502 Opcodes. Archived 2016-01-14 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Breaking NES Book – 6502 Core (PDF) (B5 ed.). 2022-06-24. pp. 61–62. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2024-04-12. Retrieved 2023-12-24.

The arrival of any interrupt is reflected on flag B, the output of which (B_OUT) forces the processor to execute a BRK instruction ...

- ^ "6502 BRK and B bit". VisualChips. Archived from the original on 2021-04-05. Retrieved 2021-05-15.

- ^ "FLAGS". ogamespec. Retrieved 2021-05-15.

B_OUT; INTERNAL DATA BUS (DB)

- ^ a b "FAQ 400 800 XL XE: What are SALLY, ANTIC, CTIA/GTIA/FGTIA, POKEY, and FREDDIE?". Archived from the original on 19 July 2020.

named SALLY by Atari engineers, but [support documents call it] "6502 (Modified)", "6502 Modified", "Custom 6502", or "6502C". [..] SALLY 6502 chips are never marked "6502C" but, other than the UMC UM6502I, always [marked] C014806. [..] [Other] chips marked "6502C" [..] are NOT the Atari "6502C" but [standard 6502] certified for 4MHz

- ^ "6502 (modified) CPU Microprocessor". ATARI 1200 XL HOME COMPUTER FIELD SERVICE MANUAL. ATARI. February 1983.

- ^ a b c d e f g 1982 MOS Technology Data Catalog (PDF obtained from bitsavers.org)

- ^ "AtariAge: A2600 clone, 6591 chip pinout". 3 August 2015. Archived from the original on 2020-08-05. Retrieved 2019-07-22.

- ^ "Hackaday: The teensiest Atari 2600 ever". 7 April 2012. Archived from the original on 2019-07-22. Retrieved 2019-07-22.