Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

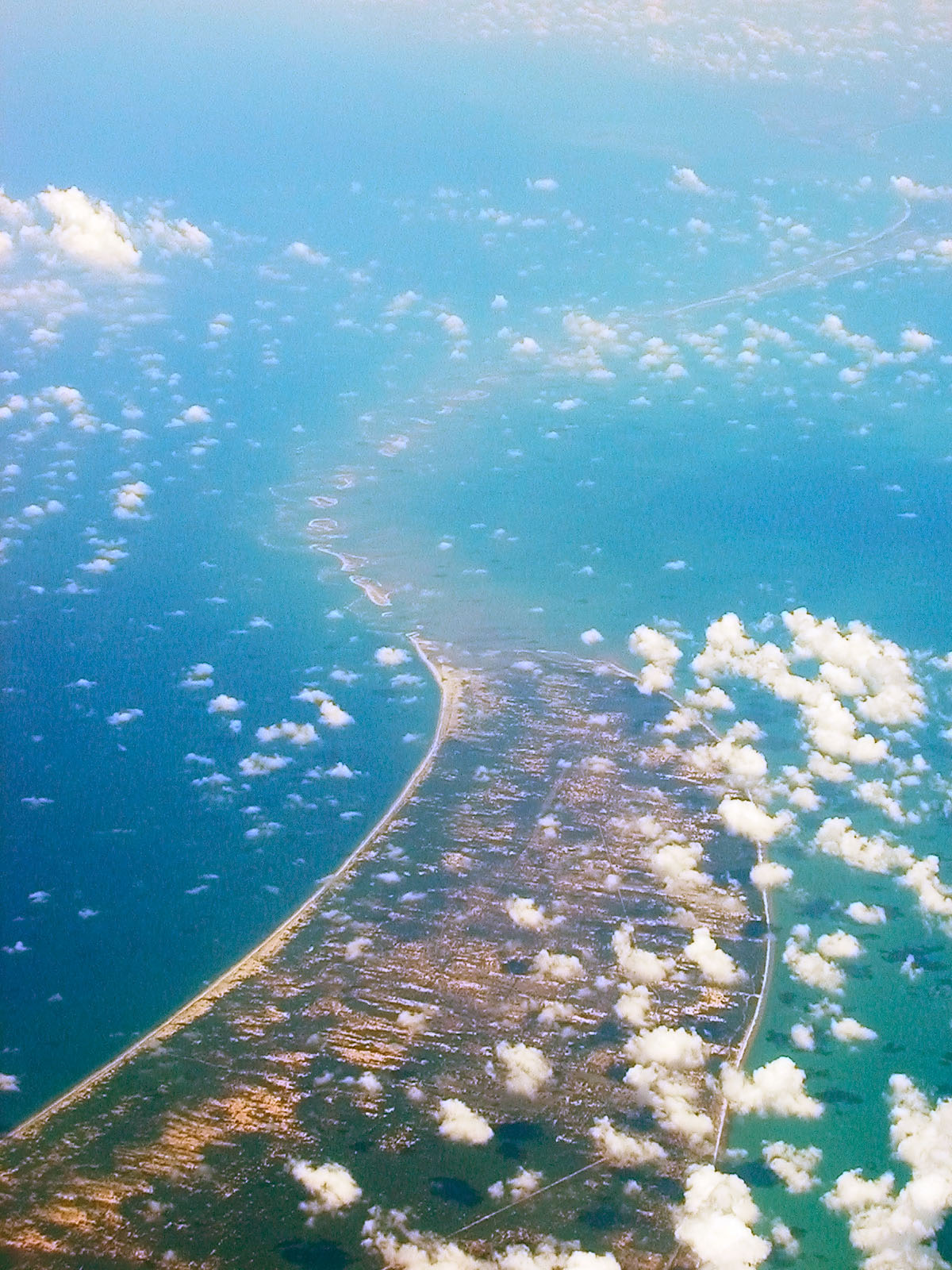

Adam's Bridge

View on Wikipedia

Adam's Bridge,[a] also known as Rama's Bridge or Rama Setu,[c] is a chain of natural limestone shoals between Pamban Island, also known as Rameswaram Island, off the southeastern coast of Tamil Nadu, India, and Mannar Island, off the northwestern coast of Sri Lanka. Geological evidence suggests that the bridge was formerly a land connection between India and Sri Lanka.[1]

The feature is 48 km (30 mi) long and separates the Gulf of Mannar (southwest) from the Palk Strait (northeast). Some regions of the bridge are dry, and the sea in the area rarely exceeds 1 metre (3 ft) in depth, making it quite difficult for boats to pass over it.[1]

Etymology

[edit]Ibn Khordadbeh's Kitāb al-Masālik wa-l-Mamālik (c. 850) refers to the structure as Set Bandhai (lit. Bridge of the Sea).[2] The name Adam's Bridge appeared probably around the time of Al-Biruni (c. 1030).[2] This appears to have been premised on the Islamic belief that Adam's Peak — where the biblical Adam fell to earth — is located in Sri Lanka, and that Adam crossed over to peninsular India via the bridge after his expulsion from the Garden of Eden.[3]

The ancient Sanskrit epic Ramayana (8th century BCE–3rd century CE) mentions a bridge constructed by the god Rama to reach the island Lanka and rescue his wife Sita from Ravana. In popular belief, Lanka is equated to present-day Sri Lanka and the bridge is described as "Rama's Setu".[4]

"... his General, the Prince of Satyrs, was named Hanumat, or with high cheek-bones; and, with workmen of such agility, he soon raised a bridge of rocks over the sea, part of which, say the Hindus, yet remains; and it is, probably, the series of rocks, to which the Muselmans or the Portuguese have given the foolish name of Adam's (it should be called Ráma's) bridge."

Geological evolution

[edit]

Due to lowered sea levels during the Last Glacial Period (115,000–11,700 years Before Present) where sea levels reached a maximum of 120 m (390 ft) below present values, the entirety of the relatively shallow Palk Strait (which reaches a maximum depth of only 35 m (115 ft)) was exposed as dry land connecting the mainland Indian subcontinent and Sri Lanka. Following the rise to present sea levels during the Holocene, by around 7,000 years ago, the strait became submerged, including the region of Adam's Bridge/Rama Setu. The islands of Adam's Bridge became emergent again following sea level falls in the region from around 5,000 years ago to the present.[5]

The bridge starts as a chain of shoals from the Dhanushkodi tip of India's Pamban Island. It ends at Sri Lanka's Mannar Island. Pamban Island is accessed from the Indian mainland by the 2 km (1.2 mi) long Pamban Bridge. Mannar Island is connected to mainland Sri Lanka by a causeway.

The lack of comprehensive field studies explains many of the uncertainties regarding the nature and origin of Adam's Bridge. It mostly consists of a series of parallel ledges of sandstone and conglomerates that are hard at the surface and grow coarse and soft as they descend to sandy banks.[6] The Marine and Water Resources Group of the Space Applications Centre (SAC) of the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) concludes that Adam's Bridge comprises 103 small patch reefs.[6] One study tentatively concludes that there is insufficient evidence to indicate eustatic emergence and that the raised reef in southern India probably results from a local uplift.[7]

Transport corridor

[edit]

In the vicinity of Adam's Bridge/Rama Setu, the water is typically only 1–3 m (3 ft 3 in – 9 ft 10 in) deep.[5] Due to the shallow waters, Adam's Bridge presents a formidable hindrance to navigation through the Palk Strait. Though trade across the India–Sri Lanka divide has been active since at least the first millennium BC, it was limited to small boats and dinghies. Larger ocean-going vessels from the west have had to navigate around Sri Lanka to reach India's eastern coast.[8] Eminent British geographer Major James Rennell, who surveyed the region as a young officer in the late 18th century, suggested that a "navigable passage could be maintained by dredging the strait of Ramisseram [sic]". However, little notice was given to his proposal, perhaps because it came from "so young and unknown an officer", and the idea was only revived 60 years later.

In 1823, Sir Arthur Cotton (then an ensign) was assigned to survey the Pamban channel, which separates the Indian mainland from the island of Rameswaram and forms the first link of Adam's Bridge. Geological evidence indicates that a land connection bridged this in the past, and some Ramanathaswamy Temple records suggest that violent storms broke the link in 1480. Cotton suggested that the channel could be dredged to enable passage of ships, but nothing was done until 1828, when Major Sim directed the blasting and removal of some rocks.[9][10]

A more detailed marine survey of Adam's Bridge was undertaken in 1837 by lieutenants F. T. Powell, Ethersey, Grieve, and Christopher, along with draughtsman Felix Jones, and operations to dredge the channel were recommenced the next year.[9][11] However, these and subsequent efforts in the 19th century did not succeed in keeping the passage navigable for any vessels except those with a light draft.[1]

Sethusamudram Shipping Canal Project

[edit]

The government of India constituted nine committees before independence, and five committees since then, to suggest alignments for a Sethusamudram canal project. Most of them suggested land-based passages across Rameswaram island, and none recommended alignment across Adam's Bridge.[12] The Sethusamudram project committee in 1956 also strongly recommended to the Union government to use land passages instead of cutting Adam's Bridge because of the several advantages of land passage.[13]

In 2005, the government of India approved a multi-million dollar Sethusamudram Shipping Canal Project. This project aims to create a ship channel across the Palk Strait by dredging the shallow ocean floor near Dhanushkodi. The channel is expected to cut over 400 km (250 mi) (nearly 30 hours of shipping time) off the voyage around the island of Sri Lanka. This proposed channel's current alignment requires dredging through Adam's Bridge.

Indian political parties including the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK), Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD), Janata Dal (Secular) (JD(S)) and some Hindu organisations oppose dredging through the shoal on religious grounds. The contention is that Adam's Bridge is identified popularly as the causeway described in the Ramayana. The political parties and organisations suggest alternate alignment for the channel that avoids damage to Adam's Bridge.[14][15] The then state and central governments opposed such changes, with the Union Shipping Minister T. R Baalu, who belongs to the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam and a strong supporter of the project maintaining that the current proposal was economically viable and environmentally sustainable and that there were no other alternatives.[16][17][18]

Opposition to dredging through this causeway also stems from concerns over its impact on the area's ecology and marine wealth, potential loss of thorium deposits in the area and increased risk of damage due to tsunamis.[19] Some organisations oppose this project on economic and environmental grounds and claim that proper scientific studies were not conducted before undertaking this project.[20]

Proposed Road and Rail Bridge

[edit]The Palk Strait Bridge is a proposed road and rail sea bridge and tunnel that would cross the Palk Strait roughly over, or parallel to, Adam's Bridge. It would span from Dhanushkodi at the tip of Pamban Island in India, to Talaimannar on Mannar Island in Sri Lanka, and would be used for both industrial/economic purposes and to boost tourism. The bridge was first seriously proposed by the Indian and Sri Lankan governments in 2002, shelved after security-related objections by the then-Governor of Tamil Nadu, and revived for serious consideration in 2023.[21] As of August 2024, its status is that the feasibility studies are nearing completion.[22]

Religious significance

[edit]Hinduism

[edit]

The ancient Sanskrit epic Ramayana, in the Yuddhakanda, mentions a bridge constructed by the god Rama with aid from an army of Vanaras (monkeys or forest-dwellers) to reach the island Lanka and rescue his wife Sita from Ravana.

In popular belief, Lanka is equated to present-day Sri Lanka.[4] However, such a correspondence is not explicit in the Ramayana and a few verses can even be held to be against such an identification;[23] some Sanskrit sources of the first millennium emphasise on the distinction.[4] Robert P. Goldman — who edited the Princeton translation of the epic into English — characterises most of the Ramayana, including the Lanka Kanda, as "kind of [an] elaborate fairy tale" by design; attempts to probe into its historicity were misguided.[23][d] John Brockington, noted for his scholarship on Hindu epics, concurs.[24]

In extant historical sources, the equation between the two islands appears for the first time only in the Kasakudi Copper Plates of Nandivarman II (r. late-8th century) pertaining to the conquest of Sri Lanka by one of his ancestors; as Ramayana took a life of its own under the succeeding Cholas, the identification profferred, justifying their imperial ambitions to invade the island.[4] The link would then be co-opted by the Aryacakravarti dynasty of Jaffna in presenting themselves as the guardians of the bridge.[4] Nonetheless, two reputed medieval commentaries on the Ramayana — Ramanujiya (drafted c. 1500 by Ramanuja) and Tattvadipika (drafted c. 1550 by Mahesvaratirtha) — continued to make a distinction between Lanka and Sri Lanka.[25]

Islam

[edit]Muslim tradition holds that Adam's Bridge was crossed by Adam following his expulsion from the Garden of Eden.[26][27]

Controversy over origin claims

[edit]Religious beliefs that the geological structure was constructed by Rama have caused some controversy as believers reject the natural provenance of Adam's Bridge. S. Badrinarayanan, a former director of the Geological Survey of India,[28] a spokesman for the Indian government in a 2008 court case,[29] the Madras High Court,[30] and an episode from the Science Channel series What on Earth? have claimed that the structure is man-made.[31]

In the What on Earth? episode, those claiming that Adam's Bridge was constructed based their arguments on vague speculation, false implications, and the point that – as with many geological formations – not every detail of its formation has been incontrovertibly settled.[32] Indian Geologist C. P. Rajendran described the ensuing media controversy as an "abhorrent" example of the "post-truth era, where debates are largely focused on appeals to emotions rather than factual realities".[33][34]

NASA said that its satellite photos had been egregiously misinterpreted to make this point during the protests against Sethusamudram Shipping Canal Project. NASA noted: "The images reproduced on the websites may well be ours, but their interpretation is certainly not ours. Remote sensing images or photographs from orbit cannot provide direct information about the origin or age of a chain of islands, and certainly, cannot determine whether humans were involved in producing any of the patterns seen."[35]

A report from the Archaeological Survey of India found no evidence for the structure being anything but a natural formation.[36] The Archaeological Survey of India and the government of India informed the Supreme Court of India in a 2007 affidavit that there was no historical proof of the bridge being built by Rama.[37] In 2017 the Indian Council of Historical Research (ICHR) announced a pilot study into the origins of the structure,[38] but went on to shelve it.[39]

In 2007, the Sri Lankan Tourism Development Authority sought to promote religious tourism from Hindu pilgrims in India by including the phenomenon as one of the points on its "Ramayana Trail", celebrating the legend of Prince Rama. Some Sri Lankan historians have condemned the undertaking as "a gross distortion of Sri Lankan history".[40] The idea of Rama Setu as a sacred symbol to be appropriated for political purposes strengthened in the aftermath of protests against the Sethusamudram Shipping Canal Project.[41]

See also

[edit]- Adam's Bridge Marine National Park

- Bimini Road, underwater rock formation in the Bahamas

- Coral reefs in India

- Pamban Bridge, railway bridge in the area

Notes

[edit]- ^ Sinhala: ආදම්ගේ පාලම ādamgē pālama; Tamil: ஆதாம் பாலம் ātām pālam

- ^ also spelled Ram Sethu, Ramasethu and variants.

- ^ Sinhala: රාමගේ පාලම rāmagē pālama; Tamil: ராமர் பாலம் Rāmar pālam; Sanskrit: रामसेतु rāmasetu[b]

- ^ Goldman and other scholars emphasise on the abrupt change of the narrative from Book Two (Ayodhyakanda) to Book Three (Aranyakanda) and onwards — that deals with Rama's efforts to bring back Sita and subsequent exploits in Lanka — from "pseudo-historical" to the "totally fantasied".[23] Goldman cautions against attempts to recover any historical stratum from these books; he reiterates Jacobi's opinion that for the intended audience of the text, South of the Gangetic Plains was terra incognita where the hero can be made to cross over into the supernatural realm.[23] He concludes: "As to the kingdoms of the demons and the monkeys, it is our conviction that they never existed anywhere except in the mind of the poets and more importantly, in the hearts of the countless millions [] who have been charmed and deeply moved by this strange work."[23]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Adam's bridge". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007. Archived from the original on 13 January 2008. Retrieved 14 September 2007.

- ^ a b Suckling, Horatio John (1876). Ceylon: A General Description of the Island, Historical, Physical, Statistical. Containing the Most Recent Information. Chapman & Hall. pp. 58-59.

- ^ Ricci, Ronit (2011). Islam Translated: Literature, Conversion, and the Arabic Cosmopolis of South and Southeast Asia. University of Chicago Press. p. 136. ISBN 9780226710884.

- ^ a b c d e Henry, Justin W. (2019). "Explorations in the Transmission of the Ramayana in Sri Lanka". South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies. 42 (4): 732–746. doi:10.1080/00856401.2019.1631739. ISSN 0085-6401. S2CID 201385559.

- ^ a b Dubey, K.M.; Chaubey, A.K.; Gaur, A.S.; Joglekar, M.V. (January 2023). "Evolution of Ramasetu region as a link between India and Sri Lanka during the late Pleistocene and Holocene". Quaternary Research. 111: 166–176. doi:10.1017/qua.2022.41. ISSN 0033-5894.

- ^ a b Bahuguna, Anjali; Nayak, Shailesh; Deshmukh, Benidhar (1 December 2003). "IRS views the Adams bridge (bridging India and Sri Lanka)". Journal of the Indian Society of Remote Sensing. 31 (4): 237–239. doi:10.1007/BF03007343. ISSN 0255-660X. S2CID 129785771.

- ^ D. R. Stoddart; C. S. Gopinadha Pillai (1972). "Raised Reefs of Ramanathapuram, South India". Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers. 56 (56): 111–125. doi:10.2307/621544. ISSN 0020-2754. JSTOR 621544.

- ^ Francis Jr., Peter (2002). Asia's Maritime Bead Trade: 300 B.C. to the Present. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-2332-0.

- ^ a b Hunter, Sir William Wilson (1886). The Imperial Gazetteer of India. Trübner & co. pp. 21–23.

- ^ Digby, William (1900). General Sir Arthur Cotton, R. E., K. C. S. I.: His Life and Work. Hodder & Stoughton. pp. 15–16.

- ^ Dawson, Llewellyn Styles (1885). Memoirs of hydrography. Keay. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-665-68425-8.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Sethusamudram Corporation Limited–History Archived 14 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Use land based channel and do not cut through Adam bridge:Sethu samudram project committee report to Union Government". 30 September 2007. Archived from the original on 13 October 2007. Retrieved 15 October 2007.

"In these circumstances we have no doubt, whatever that the junction between the two sea should be effected by a Canal; and the idea of cutting a passage in the sea through Adam's Bridge should be abandoned.

- ^ "Ram Setu a matter of faith, needs to be protected: Lalu". NewKerela.com. 21 September 2007. Retrieved 24 September 2007.

- ^ "Rama is 'divine personality' says Gowda". MangaoreNews.com. 22 September 2007. Archived from the original on 21 April 2008. Retrieved 24 September 2007.

- ^ "IndianExpress.com–Sethu: DMK chief sticks to his stand". Archived from the original on 21 April 2008. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- ^ "Latest India News @ NewKerala.Com, India".

- ^ "indianexpress.com". Archived from the original on 21 April 2008. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- ^ "Thorium reserves to be disturbed if Ramar Sethu is destroyed". The Hindu. 5 August 2007. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 24 September 2007.

- ^ "The Sethusamudram canal project". www.rediff.com.

- ^ Raju, Adluri Subramanyam (8 July 2024). "Bridge that could boost India and Sri Lanka ties". Hindustan Times. Retrieved 26 August 2024.

- ^ "Feasibility study on proposal to establish land connectivity with India in final stages, says Sri Lankan President". The Indian Express. 16 June 2024. Retrieved 9 July 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Goldman, Robert P., ed. (1984). The Rāmāyaṇa of Vālmīki: An Epic of Ancient India. Princeton Library of Asian Translations. Vol. I: Bālakāṇḍa. Translated by Goldman, Robert P. Princeton University Press. pp. 23–30.

- ^ Rāma the Steadfast: An Early Form of the Rāmāyaṇa. Translated by Brockington, John; Brockington, Mary. London: Penguin. 2006. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-14-196029-6.

Many attempts have been made to identify Lankā and Kiskindhā, the vānaras' city, with real sites on mainland India, and especially to equate Rāvana's kingdom with the island in modern times renamed Śrī Lanka, but there is nothing in the first stage of the text to indicate that they are anything more than the product of the storytellers' imaginations, with little help even from travellers' tales.

- ^ Goldman, Robert P., ed. (1996). The Rāmāyaṇa of Vālmīki: An Epic of Ancient India. Princeton Library of Asian Translations. Vol. V: Sundarakāṇḍa. Translated by Goldman, Sally J.; Goldman. Princeton University Press. p. 359. ISBN 0-691-06662-0.

- ^ Ricci, R. (2019). Banishment and Belonging: Exile and Diaspora in Sarandib, Lanka and Ceylon. Asian Connections. Cambridge University Press. pp. 178–179. ISBN 978-1-108-57211-8.

- ^ "Adams Bridge". Encyclopedia.com. 23 May 2018.

- ^ "rediff.com: Adam's Bridge is a man-made structure". specials.rediff.com.

- ^ "Ram himself destroyed Setu, govt tells SC - Times Of India". 23 October 2012. Archived from the original on 23 October 2012.

- ^ Gohain, Manash Pratim (24 March 2017). "Indian Council of Historical Research to look for material evidence of Rama Setu - India News". The Times of India. Retrieved 29 October 2022.

- ^ Shahane, Girish (20 December 2017). "Raptures over Ram Setu video underline what's wrong with our government and sections of the media". Scroll.in. Retrieved 8 April 2021.

- ^ "A bridge that Lord Ram built - myth or reality?". DW. Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 10 April 2019.

- ^ C.P. Rajendran. "A Post-Truth Take on the Ram Setu". The Wire. Retrieved 10 April 2019.

- ^ "'Place faith in science, and not in faith-based culture'". The Hindu. 6 May 2019. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 7 March 2021.

popular hegemonic culture had so successfully been able to impress upon many people that even scientific organisations were not ready to explore the myth around Ram Setu

- ^ Kumar, Arun (14 September 2007). "Space photos no proof of Ram Setu: NASA". Hindustan Times. Archived from the original on 22 January 2008. Retrieved 18 September 2007.

"The mysterious bridge was nothing more than a 30 km long, naturally occurring chain of sandbanks called Adam's bridge", [NASA official Mark] Hess had added. "NASA had been taking pictures of these shoals for years. Its images had never resulted in any scientific discovery in the area.

- ^ "Myth vs Science". Frontline. 5 October 2007. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- ^ "No evidence to prove existence of Ram". Rediff.com. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- ^ "Twenty research scholars to get training to find 'truth' of Ram Sethu". The Indian Express. 25 March 2017. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- ^ "ICHR not to conduct study whether Ram Setu man made, natural". The Times of India. 8 April 2018. Retrieved 11 February 2020.

- ^ Kumarage, Achalie (23 July 2010). "Selling off the history via the 'Ramayana Trail'". Daily Mirror. Colombo: Wijeya Newspapers Ltd. Archived from the original on 25 July 2010. Retrieved 23 July 2010.

the Tourism Authority is imposing an artificial [history] targeting a small segment of Indian travellers, specifically Hindu fundamentalists...

- ^ Jaffrelot, Christophe (2008). "Hindu Nationalism and the (Not So Easy) Art of Being Outraged: The Ram Setu Controversy". South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal (2). doi:10.4000/samaj.1372. ISSN 1960-6060.

- ^ commons:File:NASA_bathymetric_world_map.jpg

External links

[edit]- Photo essay on the Palk Strait. Archived 5 April 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- Ram Sethu campaign by Hindu Organizations Archived 27 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- "Physical features of Adam's Bridge interpreted from ICESat-2 based high-resolution digital bathymetric elevation model". Scientific Reports. 14 (1): 14896. 28 June 2024. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-65908-2. PMC 11213924.