Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

| Nala | |

|---|---|

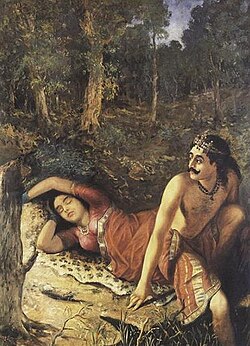

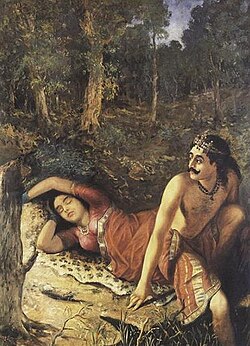

Nala abandons Damayanti out of guilt, painting by Raja Ravi Varma | |

| Personal Information | |

| Aliases |

|

| Gender | Male |

| Family | Virasena (father) Pushkara (younger brother) |

| Spouse | Damayanti |

| Children | Indrasena (son) Indrasenā (daughter) |

| Nationality | Nishadha |

Nala (Sanskrit: नल) is a legendary king of ancient Nishadha kingdom and the central protagonist of the Nalopakhyana, a sub-narrative within the Indian epic Mahabharata, found in its third book, Vana Parva (Book of the Forest). He is renowned for his valor, wisdom, and exceptional skill in charioteering. His story revolves around his love for Damayanti, the princess of Vidarbha, and his struggle to reclaim his lost fortune.

According to Nalopakhyana, despite his virtues, Nala falls victim to a curse from the malicious deity Kali, who influences him to lose his kingdom in a game of dice against his brother Pushkara. Forced into exile, he abandons Damayanti in the forest, believing she would suffer less without him. Wandering in disguise under the name Bahuka after being transformed by a serpent’s bite, Nala takes service as a charioteer in the court of King Rituparna of Ayodhya, where he acquires new skills in gambling and horsemanship. Meanwhile, Damayanti devises a plan to find him. Their eventual reunion leads to Nala reclaiming his true identity, allowing him to challenge Pushkara in a new game and restore his kingdom.[1]

The story of Nala has had a profound influence on Indian literature, folklore, and performing arts. It has been retold in various Sanskrit and regional texts, including adaptations in Tamil, Telugu, Kannada, and Bengali literature. The 12th-century poet Sriharsha composed Naishadhiya Charita, an epic based on Nala’s tale, which is considered one of the five great Sanskrit mahakavyas. Nala is also regarded as a great cook and the cookbook Pakadarpanam (Sanskrit: पाकदर्पण) is attributed to him.[2]

Biography

[edit]Nala's biography is attested in the Nalopakhyana section of Vana Parva, the third book of the Mahabharata.[3]

Early life and marriage

[edit]Nala is born to Virasena, the king of Nishada Kingdom, and grows up into an extremely handsome youth, renowned for his righteousness, exceptional charioteering skills, and devotion to dharma. His virtues are widely extolled, and his reputation reaches far and wide, desired by many women. Meanwhile, Damayanti, the princess of Vidarbha, grows into a woman of exceptional beauty. She and Nala hear tales of each other’s qualities and fall in love despite never having met. While Nala is in the palace garden, a group of golden-winged swans arrives at the lake. Amused, he captures one of them, which then addresses him with a proposal: if released, it will fly to Vidarbha and speak of his virtues to Damayanti. Accepting this offer, Nala sets the swan free. The swan fulfills its promise, flying to Vidarbha and praising Nala before Damayanti, further fostering her admiration for him. In return, the swans carry her admiration back to Nala. Deeply drawn to each other, Nala prepares to attend Damayanti’s svayamvara, the ceremony where she will choose her husband. Meanwhile, the gods Indra, Agni, Varuna, and Yama, having heard of Damayanti’s beauty, also desire to marry her. On their way to the svayamvara, they encounter Nala and request that he deliver their proposal to Damayanti. Granted invisibility, Nala enters her chamber and conveys their message. However, Damayanti remains steadfast in her love for Nala and chooses him over the gods. To test her devotion, the gods assume Nala’s form during the svayamvara, making it difficult for her to distinguish him. Through divine intuition, she identifies the real Nala and places the nuptial garland around his neck. Pleased with their love, the gods bestow blessings upon Nala: Agni promises to aid him whenever called, Yama grants him unwavering righteousness, Varuna ensures he will never lack water, and Indra guarantees him moksha (liberation) upon completing a sacrifice.[3]

Exile

[edit]Kali, the deity of discord, harbors resentment toward Nala for winning Damayanti’s hand and vows to ruin him. Along with Dvapara, he waits for an opportunity to influence Nala’s fate. After twelve years, Kali finds an opening when Nala fails to wash his feet before performing his evening prayers. Exploiting this lapse in ritual purity, Kali takes possession of Nala’s mind, corrupting his judgment. Under Kali’s influence, Nala becomes addicted to gambling and challenges his younger brother, Pushkara, to a game of dice. Manipulated by Kali and Dvapara, Nala ignores pleas from Damayanti and citizens, and suffers continuous losses, eventually forfeiting his kingdom, wealth, and status. As his misfortunes worsen, Damayanti sends their children, Indrasena and Indrasenā, to her father’s kingdom for safety. Ultimately, Nala is left with nothing but a single garment, and Pushkara decrees that anyone who assists him will be executed. Stripped of his power and possessions, Nala wanders into the forest. When he attempts to catch golden birds for food, they fly away with his last piece of clothing, revealing themselves to be the dice that had caused his ruin. Fearing for Damayanti’s safety, Nala urges her to seek refuge in her father's palace. She refuses, vowing to stay by his side. That night, as she sleeps, Nala, believing she will be safer without him, cuts a piece of her garment and abandons her.[3]

During his exile, Nala comes across a raging fire and hears a voice calling for help. He discovers the serpent Karkotaka, who is trapped in the flames due to a curse. Nala rescues him, and in return, Karkotaka bites him, altering his appearance and making him unrecognizable. The serpent explains that this transformation is a protective measure and that the venom will weaken Kali’s hold over him. He also provides Nala with two divine garments, which will restore his true form when worn. Following Karkotaka’s guidance, Nala assumes the identity of Bahuka, an expert charioteer, and travels to Ayodhya. There, he enters the service of King Rituparna, offering his exceptional charioteering skills in exchange for knowledge of gambling. Despite his altered form, Nala’s skills and demeanor intrigue those around him. Each evening, he recites verses lamenting a man who has lost everything, arousing the curiosity of his fellow servants, particularly Jivala and Varsneya.[3]

Rediscovery and Reunion

[edit]Meanwhile, Damayanti has been found by her father and taken back to Vidarbha. She remains committed to searching for Nala, despite widespread assumptions of his demise. When the messenger Parnada reports about Bahuka, the skilled charioteer in Ayodhya who responds to the verses with ones only Nala could know, she devises a plan. She instructs a Brahmin to inform Rituparna that she will hold a second svayamvara the following day, knowing that only Nala can drive a chariot fast enough to reach Vidarbha within that time. As expected, Rituparna, eager to win Damayanti’s hand, orders Bahuka to drive him to Vidarbha with great speed. During the journey, Rituparna demonstrates his ability to count the leaves on a tree at a glance, showcasing his mastery of Akshahridaya (the art of gambling). In exchange, Nala reveals his expertise in horse-riding (Ashvahridaya), and they exchange their knowledge. At the moment he gains this new knowledge, Nala expels Kali’s influence from his body.[3]

Upon their arrival in Vidarbha, Rituparna is surprised to find no actual preparations for a swayamvara and realizes he has been misled. Meanwhile, Damayanti, hearing the roar of the approaching chariot, suspects that Nala is the driver and sends her maid Keshini to investigate. Keshini tests Bahuka by quoting the verses; he replies with Nala’s. Although Nala does not reveal his identity, his emotions betray him when he hears of Damayanti’s suffering. Damayanti instructs Kesini to closely observe Bahuka’s actions. She notes several supernatural qualities:

- He does not need to lower his head when passing through doorways, as the upper sill lifts on its own.

- He moves through crowds without obstruction, as people instinctively make way for him.

- Empty water pots fill instantly when he gazes upon them.

- A blade of grass catches fire when he stretches it toward the sun.

- Fire does not burn him, even when he touches it.

- When he crushes a flower, it blooms again, appearing more vibrant and fragrant.

Remembering that Nala was an exceptional cook, Damayanti requests food prepared by Bahuka. Upon tasting it, she recognizes the distinct flavor of Nala’s cooking, confirming her suspicions. As a final test, Damayanti sends their children, Indrasena and Indrasenā, to Bahuka. Overcome with emotion, Bahuka embraces them and weeps. When questioned, he claims he is moved because they resemble two children he once knew. Finally, Damayanti confronts him, accusing him of abandoning her in the forest. Overwhelmed with emotion, Nala blames Kali and expresses pain at the second svayamvara. Damayanti explains it was a ruse and affirms her fidelity. Vayu, the wind god, affirms Damayanti’s faithfulness. Nala then dons the divine garments provided by Karkotaka, restoring his true form and the couple is reunited.[3]

King Bhima receives Nala with joy. Rituparna congratulates him and asks forgiveness for mistreating him, which Nala grants, gifting Rituparna his knowledge of horse mastery. Nala then returns to Niṣadha with an escort and challenges Puṣkara to a rematch. Confident, Puṣkara accepts, hoping to claim Damayanti. This time, Nala wins decisively, regaining his kingdom and all that he had lost. However, in an act of magnanimity, he forgives Pushkara. Nala rules wisely, restoring prosperity to his people.[3]

The story has also been adapted into the 12th century text Nishadha Charita, one of the five mahakavyas (great epic poems) in the canon of Sanskrit literature, where few additional plot details are invented.[4][5]: 136

Translations and student editions

[edit]- Norman Mosley Penzer translated the tale of Nala and Damayanti in 1926.[6]

- The story of Nala and Damayanti has introduced students to the study of Sanskrit since at least the early 19th century, when Franz Bopp published an introductory text Nalus, carmen sanscritum e Mahabharato edidit, Latine vertit, et adnotationi illustravit, Franciscus Bopp (1819).

- Later, the American Sanskrit scholar Charles Rockwell Lanman used the story of Nala and Damayanti as the first text in his introductory A Sanskrit Reader: Text and Vocabulary and Notes (1883).

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ J. A. B. van Buitenen (1981). The Mahabharata, Volume 2. University of Chicago Press. pp. 318–322. ISBN 978-0-226-84664-4.

- ^ Bhojanam, Nala (30 December 2007). "Nala Bhojanam".

- ^ a b c d e f g Puranic Encyclopedia: a comprehensive dictionary with special reference to the epic and Puranic literature, Vettam Mani, Motilal Banarsidass, Delhi, 1975, p. Damayantī.

- ^ The Indian Encyclopaedia. Genesis Publishing. 2002. p. 5079. ISBN 9788177552577.

- ^ C.Kunhan Raja. Survey of Sanskrit Literature. Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan. pp. 136, 146–148.

- ^ S. M. E. (April 1927). "Nala and Damayanti by Norman M. Penzer". The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland (2): 363–364. JSTOR 25221149.

Further reading

[edit]- Dallapiccola, Anna Libera (2002). Dictionary of Hindu Lore and Legend. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-51088-9.

- Doniger, Wendy (1999). "Chapter 3: Nala and Damayanti, Odysseus and Penelope". Splitting the Difference: Gender and Myth in Ancient Greece and India. University of Chicago Press. pp. 133–204. ISBN 978-0-226-15640-8.

- Jours d'amour et d'épreuve, l'histoire du roi Nala, pièce de Kathakali (Nalacaritam) de Unnâyi Vâriyar, (XVIIè-XVIIIè siècle), traduction du malayâlam, introduction et notes par Dominique Vitalyos, Gallimard, Connaissance de l'Orient, 1995.

External links

[edit]- The Naishadha-charita (story of Nala and Damayanti) English translation by K. K. Handiqui [proofread] (includes glossary)

- Hindi Story of Nal Damyanti at ajabgjab.com