Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

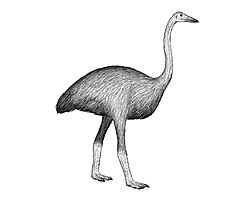

Elephant bird

View on WikipediaThis article has an unclear citation style. (August 2025) |

| Elephant birds Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Aepyornis maximus skeleton and egg | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Infraclass: | Palaeognathae |

| Clade: | Novaeratitae |

| Order: | †Aepyornithiformes Newton, 1884[1] |

| Type species | |

| †Aepyornis maximus Hilaire, 1851

| |

| Genera | |

Elephant birds are extinct flightless birds belonging to the order Aepyornithiformes that were native to the island of Madagascar. They are thought to have gone extinct around 1000 AD, likely as a result of human activity. There are three currently recognised species, one in the genus Mullerornis, and two in Aepyornis. Aepyornis maximus is possibly the largest bird to have ever lived, with their eggs being the largest known for any amniote. Elephant birds are palaeognaths (whose flightless representatives are often known as ratites), and their closest living relatives are kiwi (found only in New Zealand), suggesting that ratites did not diversify by vicariance during the breakup of Gondwana but instead convergently evolved flightlessness from ancestors that dispersed more recently by flying.

Discovery

[edit]Elephant birds have been extinct since at least the 17th century. Étienne de Flacourt, a French governor of Madagascar during the 1640s and 1650s, mentioned an ostrich-like bird, said to inhabit unpopulated regions, although it is unclear whether he was repeating folk tales from generations earlier. In 1659, Flacourt wrote of the "vouropatra – a large bird which haunts the Ampatres and lays eggs like the ostriches; so that the people of these places may not take it, it seeks the most lonely places."[2][3] There has been speculation, especially popular in the latter half of the 19th century, that the legendary roc from the accounts of Marco Polo was ultimately based on elephant birds, but this is disputed.[4]

Between 1830 and 1840, European travelers in Madagascar saw giant eggs and eggshells.[3] British observers were more willing to believe the accounts of giant birds and eggs because they knew of the moa in New Zealand.[3] In 1851 the genus Aepyornis and species A. maximus were scientifically described in a paper presented to the Paris Academy of Sciences by Isidore Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, based on bones and eggs recently obtained from the island, which resulted in wide coverage in the popular presses of the time, particularly due to their very large eggs.[4]

Two whole eggs have been found in dune deposits in southern Western Australia, one in the 1930s (the Scott River egg) and one in 1992 (the Cervantes egg); both have been identified as Aepyornis maximus rather than Genyornis newtoni, an extinct giant bird known from the Pleistocene of Australia. It is hypothesized that the eggs floated from Madagascar to Australia on the Antarctic Circumpolar Current. Evidence supporting this is the finding of two fresh penguin eggs that washed ashore on Western Australia but may have originated in the Kerguelen Islands, and an ostrich egg found floating in the Timor Sea in the early 1990s.[5]

Taxonomy and biogeography

[edit]Like the ostrich, rhea, cassowary, emu, kiwi and extinct moa, elephant birds were ratites; they could not fly, and their breast bones had no keel. Because Madagascar and Africa separated before the ratite lineage arose,[6] elephant birds are thought to have dispersed and become flightless and gigantic in situ.[7]

More recently, it has been deduced from DNA sequence comparisons that the closest living relatives of elephant birds are New Zealand kiwi,[8] though the split between the two groups is deep, with the two lineages being estimated to have diverged from each other around 54 million years ago, during the early Eocene epoch.[9]

Placement of Elephant birds within Palaeognathae, after:[10][11]

| Paleognathae |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The ancestors of elephant birds are thought to have arrived in Madagascar well after Gondwana broke apart. The existence of possible flying palaeognathae in the Miocene such as Proapteryx further supports the view that ratites did not diversify in response to vicariance. Gondwana broke apart in the Cretaceous and their phylogenetic tree does not match the process of continental drift. Madagascar has a notoriously poor Cenozoic terrestrial fossil record, with essentially no fossils between the end of the Cretaceous (Maevarano Formation) and the Late Pleistocene.[12] Complete mitochondrial genomes obtained from elephant birds eggshells suggest that Aepyornis and Mullerornis are significantly genetically divergent from each other, with molecular clock analyses estimating the split at around 27-30 million years ago, during the Oligocene epoch.[9][13]

Species

[edit]Up to 10 or 11 species in the genus Aepyornis have been described,[14] but the validity of many have been disputed, with numerous authors treating them all in just one species, A. maximus. Up to three species have been described in Mullerornis.[15] A major systematic review by Hansford and Turvey (2018) based on morphological analysis recognised only four valid elephant bird species, Aepyornis maximus, Aepyornis hildebrandti, Mullerornis modestus, and the new species and genus Vorombe titan to accommodate the largest elephant bird remains.[16] However, the validity of Vorombe titan was later questioned by genetic sequencing data, which did not find Vorombe distinct from Aepyornis, and it has been suggested that specimens assigned to Vorombe merely represent large (perhaps female) specimens of A. maximus.[13] Eggshells that have had their DNA sequenced from the far north of Madagascar may represent a third species of Aepyornis, due to their genetic distinctiveness from the other two species, but the lack of skeletal remains from this region renders this currently inconclusive.[13]

- Order Aepyornithiformes Newton 1884 [Aepyornithes Newton 1884][14]

- Genus Aepyornis Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire 1850[17] (Synonym: Vorombe Hansford & Turvey 2018)

- Aepyornis hildebrandti Burckhardt, 1893

- Aepyornis maximus Hilaire, 1851

- Genus Mullerornis Milne-Edwards & Grandidier 1894

- Mullerornis modestus (Milne-Edwards & Grandidier 1869) Hansford & Turvey 2018

- Genus Aepyornis Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire 1850[17] (Synonym: Vorombe Hansford & Turvey 2018)

All elephant birds are usually placed in the single family Aepyornithidae Bonaparte, 1853,[16] but some authors suggest Aepyornis and Mullerornis should be placed in separate families within the Aepyornithiformes, with the latter placed into Mullerornithidae Lamberton, 1934.[13]

Description

[edit]

Elephant birds were large sized birds (the largest reaching 3 metres (9.8 ft) tall in normal standing posture) that had vestigial wings, long legs and necks, with small heads relative to body size, which bore straight, thick conical beaks that were not hooked. The skulls of elephant bird species differ little from each other except in size, though the front part of the skull in Mulleronis is less robustly built than in Aepyornis. The tops of elephant bird skulls display punctuated marks, which may have been attachment sites for fleshy structures or head feathers. The spinal column is suggested to have been made up of 24 free unfused vertebrae, 16-17 cervical vertebrae in the neck, and 6-7 thoracic vertebrae. The pelvis of Aepyornis is robust and all its constituent elements (pubis, ilium and vertebrae) heavily fused to each other. The pelvis of Mulleronis is generally 3 times wider than long. The hindlimb bones, especially the femur and tibiotarsus, are very robust (proportionally stocky/thick) in Aepyornis, with the femur of Aepyornis being distinctly short and wide. The hindlimb bones were somewhat more gracile in Mullerornis. The terminal claw-bearing phalanges in the feet are uncurved and relatively broad, though somewhat more elongate and sharper in shape in Mullerornis.[18]

Mullerornis is the smallest of the elephant birds, with a body mass of around 80 kilograms (180 lb),[13] with its skeleton much less robustly built than Aepyornis.[19] A. hildebrandti is thought to have had a body mass of around 230–285 kilograms (507–628 lb).[13] Estimates of the body mass of Aepyornis maximus span from around 275 kilograms (606 lb)[20] to 700–1,000 kilograms (1,500–2,200 lb)[13] making it one of the largest birds ever, alongside Dromornis stirtoni and Pachystruthio dmanisensis.[21][22] Females of A. maximus are suggested to have been larger than the males, as is observed in other ratites.[13]

Biology

[edit]

Examination of brain endocasts has shown that both A. maximus and A. hildebrandti had greatly reduced optic lobes (a part of the brain that processes visual information), compared to most other ratites, similar to those of their closest living relatives, the kiwis, and consistent with a similar nocturnal lifestyle. The optic lobes of Mullerornis were also reduced, but to a lesser degree, suggestive of a nocturnal or crepuscular lifestyle. A. maximus had relatively larger olfactory bulbs than A. hildebrandti, suggesting that the former occupied forested habitats where the sense of smell is more useful while the latter occupied open habitats.[23] Elephant birds probably heavily relied on their sense of smell. Morphological analysis of their ears suggests that they had relatively poor hearing.[24] Based on the proportions of their leg bones, unlike most living ratites such as ostriches, emus and rheas, but similar to moas, elephant birds are thought to have walked with a relatively slow graviportal locomotion, though the smaller Mullerornis may have been capable of somewhat more agile locomotion than the larger Aepyornis species.[18]

Diet

[edit]A 2022 isotope analysis study suggested that some specimens of Aepyornis hildebrandti were mixed feeders that had a large (~48%) grazing component to their diets, similar to that of the living Rhea americana, while the other species (A. maximus, Mullerornis modestus) were probably browsers.[25] It has been suggested that Aepyornis straightened its legs and brought its torso into an erect position in order to browse higher vegetation.[26] Some rainforest fruits with thick, highly sculptured endocarps, such as that of the currently undispersed and highly threatened forest coconut palm (Voanioala gerardii), may have been adapted for passage through ratite guts and consumed by elephant birds, and the fruit of some palm species are indeed dark bluish-purple (e.g., Ravenea louvelii and Satranala decussilvae), just like many cassowary-dispersed fruits, suggesting that they too may have been eaten by elephant birds.[27]

Growth and reproduction

[edit]Elephant birds are thought to have had a k-selective life strategy, taking at least several years from hatching to reaching maximum body size, as opposed to taking around a year to reach maximum body size from hatching as is typical of birds.[28][19] Elephant birds are suggested to have grown in periodic spurts rather than having continuous growth.[19] An embryonic skeleton of Aepyornis is known from an intact egg, around 80–90% of the way through incubation before it died. This skeleton shows that even at this early ontogenetic stage that the skeleton was robust, much more so than comparable hatchling ostriches or rheas,[29] which may suggest that hatchlings were precocial.[19]

The eggs of Aepyornis are the largest known for any amniote, and have a volume of around 5.6–13 litres (12–27 US pt), a length of approximately 26–40 centimetres (10–16 in) and a width of 19–25 centimetres (7.5–9.8 in).[19] The largest Aepyornis eggs are on average 3.3 mm (1⁄8 in) thick, with an estimated weight of approximately 10.5 kilograms (23 lb).[13] Eggs of Mullerornis were much smaller, estimated to be only 1.1 mm (3⁄64 in) thick, with a weight of about 0.86 kilograms (1.9 lb).[13] The large size of elephant bird eggs means that they would have required substantial amounts of calcium, which is usually taken from a reservoir in the medullary bone in the femurs of female birds. Possible remnants of this tissue have been described from the femurs of A. maximus.[19]

-

Eggs of Aepyornis (top left) chicken (bottom left) moa (right) and ostrich (centre)

-

Aepyornis maximus egg (far left, 1) in comparison to other eggs, including ostrich egg (centre, 3) and chicken egg (third from right, 6)

-

Well preserved egg showing porous surface

-

Egg of Aepyornis standing upright

Extinction

[edit]It is widely believed that the extinction of elephant birds was a result of human activity. The birds were initially widespread, occurring from the northern to the southern tip of Madagascar.[30] The late Holocene also witnessed the extinction of other Malagasy animals, including several species of Malagasy hippopotamus, two species of giant tortoise (Aldabrachelys abrupta and Aldabrachelys grandidieri), the giant fossa, over a dozen species of giant lemurs, the aardvark-like animal Plesiorycteropus, and the crocodile Voay.[26] Several elephant bird bones with incisions have been dated to approximately 10,000 BC which some authors suggest are cut marks, which have been proposed as evidence of a long history of coexistence between elephant birds and humans;[31] however, these conclusions conflict with more commonly accepted evidence of a much shorter history of human presence on the island and remain controversial. The oldest securely dated evidence for humans on Madagascar dates to the mid-first millennium AD.[32]

A 2021 study suggested that elephant birds, along with the Malagasy hippopotamus species, became extinct in the interval 800–1050 AD (1150–900 years Before Present), based on the timing of the latest radiocarbon dates. The timing of the youngest radiocarbon dates coincided with major environmental alteration across Madagascar by humans changing forest into grassland, probably for cattle pastoralism, with the environmental change likely being induced by the use of fire. This reduction of forested area may have had cascade effects, like making elephant birds more likely to be encountered by hunters,[33] though there is little evidence of human hunting of elephant birds. Humans may have utilized elephant bird eggs. Introduced diseases (hyperdisease) have been proposed as a cause of extinction, but the plausibility for this is weakened due to the evidence of centuries of overlap between humans and elephant birds on Madagascar.[26]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Brands 2008.

- ^ Etienne de Flacourt (1658). Histoire de la grande isle Madagascar. chez Alexandre Lesselin. p. 165. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- ^ a b c Ley, Willy (August 1966). "Scherazade's Island". For Your Information. Galaxy Science Fiction. pp. 45–55.

- ^ a b Buffetaut, Eric (6 September 2019). "Early illustrations of Aepyornis eggs (1851–1887): from popular science to Marco Polo's roc bird". Anthropozoologica. 54 (1): 111. doi:10.5252/anthropozoologica2019v54a12. ISSN 0761-3032. S2CID 203423023.

- ^ Long, J. A.; Vickers-Rich, P.; Hirsch, K.; et al. (1998). "The Cervantes egg: an early Malagasy tourist to Australia". Records of the Western Australian Museum. 19 (Part 1): 39–46. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ^ Yoder, A. D. & Nowak, M. D. (2006)

- ^ van Tuinen, M. et al. (1998)

- ^ Mitchell, K. J.; Llamas, B.; Soubrier, J.; et al. (23 May 2014). "Ancient DNA reveals elephant birds and kiwi are sister taxa and clarifies ratite bird evolution" (PDF). Science. 344 (6186): 898–900. Bibcode:2014Sci...344..898M. doi:10.1126/science.1251981. hdl:2328/35953. PMID 24855267. S2CID 206555952.

- ^ a b Grealy, Alicia; Phillips, Matthew; Miller, Gifford; et al. (April 2017). "Eggshell palaeogenomics: Palaeognath evolutionary history revealed through ancient nuclear and mitochondrial DNA from Madagascan elephant bird (Aepyornis sp.) eggshell". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 109: 151–163. Bibcode:2017MolPE.109..151G. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2017.01.005. PMID 28089793.

- ^ Takezaki, Naoko (1 June 2023). Holland, Barbara (ed.). "Effect of Different Types of Sequence Data on Palaeognath Phylogeny". Genome Biology and Evolution. 15 (6) evad092. doi:10.1093/gbe/evad092. ISSN 1759-6653. PMC 10262969. PMID 37227001.

- ^ Urantówka, Adam Dawid; Kroczak, Aleksandra; Mackiewicz, Paweł (December 2020). "New view on the organization and evolution of Palaeognathae mitogenomes poses the question on the ancestral gene rearrangement in Aves". BMC Genomics. 21 (1): 874. doi:10.1186/s12864-020-07284-5. ISSN 1471-2164. PMC 7720580. PMID 33287726.

- ^ Samonds, Karen E.; Zalmout, Iyad S.; Irwin, Mitchell T.; et al. (12 December 2009). "Eotheroides lambondrano, new middle Eocene seacow (Mammalia, Sirenia) from the Mahajanga Basin, northwestern Madagascar". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 29 (4): 1233–1243. Bibcode:2009JVPal..29.1233S. doi:10.1671/039.029.0417. ISSN 0272-4634. S2CID 59466434.

- ^ a b Brodkorb 1963.

- ^ Davies, S. J. J. F. (2003)

- ^ a b Hansford, James P.; Turvey, Samuel T. (September 2018). "Unexpected diversity within the extinct elephant birds (Aves: Aepyornithidae) and a new identity for the world's largest bird". Royal Society Open Science. 5 (9) 181295. Bibcode:2018RSOS....581295H. doi:10.1098/rsos.181295. ISSN 2054-5703. PMC 6170582. PMID 30839722.

- ^ Hume, Julian P.; Walters, Michael (2012). Extinct birds. T&AD Poyser. p. 544. ISBN 978-1-4081-5861-6.

- ^ a b Angst, Delphine; Buffetaut, Eric (2017), "Aepyornithiformes", Palaeobiology of Extinct Giant Flightless Birds, Elsevier, pp. 65–94, doi:10.1016/b978-1-78548-136-9.50003-9, ISBN 978-1-78548-136-9, retrieved 2 May 2023

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: work parameter with ISBN (link) - ^ a b c d e f Chinsamy, Anusuya; Angst, Delphine; Canoville, Aurore; Göhlich, Ursula B (1 June 2020). "Bone histology yields insights into the biology of the extinct elephant birds (Aepyornithidae) from Madagascar". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 130 (2): 268–295. doi:10.1093/biolinnean/blaa013. ISSN 0024-4066.

- ^ Hume, J. P.; Walters, M. (2012). Extinct Birds. London: A & C Black. pp. 19–21. ISBN 978-1-4081-5725-1.

- ^ Handley, Warren D.; Chinsamy, Anusuya; Yates, Adam M.; Worthy, Trevor H. (2 September 2016). "Sexual dimorphism in the late Miocene mihirung Dromornis stirtoni (Aves: Dromornithidae) from the Alcoota Local Fauna of central Australia". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 36 (5) e1180298. Bibcode:2016JVPal..36E0298H. doi:10.1080/02724634.2016.1180298. ISSN 0272-4634. S2CID 88784039.

- ^ Zelenkov, Nikita V.; Lavrov, Alexander V.; Startsev, Dmitry B.; Vislobokova, Innessa A.; Lopatin, Alexey V. (4 March 2019). "A giant early Pleistocene bird from eastern Europe: unexpected component of terrestrial faunas at the time of early Homo arrival". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 39 (2) e1605521. Bibcode:2019JVPal..39E5521Z. doi:10.1080/02724634.2019.1605521. ISSN 0272-4634. S2CID 198384367.

- ^ Torres, C. R.; Clarke, J. A. (2018). "Nocturnal giants: evolution of the sensory ecology in elephant birds and other palaeognaths inferred from digital brain reconstructions". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 285 (1890) 20181540. doi:10.1098/rspb.2018.1540. PMC 6235046. PMID 30381378.

- ^ Johnston, Peter; Mitchell, Kieren J. (26 October 2021). "Contrasting Patterns of Sensory Adaptation in Living and Extinct Flightless Birds". Diversity. 13 (11): 538. Bibcode:2021Diver..13..538J. doi:10.3390/d13110538. ISSN 1424-2818.

- ^ Hansford, James P.; Turvey, Samuel T. (April 2022). "Dietary isotopes of Madagascar's extinct megafauna reveal Holocene browsing and grazing guilds". Biology Letters. 18 (4) 20220094. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2022.0094. ISSN 1744-957X. PMC 9006009. PMID 35414222.

- ^ a b c Clarke, Simon J.; Miller, Gifford H.; Fogel, Marilyn L.; Chivas, Allan R.; Murray-Wallace, Colin V. (September 2006). "The amino acid and stable isotope biogeochemistry of elephant bird (Aepyornis) eggshells from southern Madagascar". Quaternary Science Reviews. 25 (17–18): 2343–2356. Bibcode:2006QSRv...25.2343C. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2006.02.001.

- ^ Dransfield, J. & Beentje, H. (1995)

- ^ de Ricqlès, Armand; Bourdon, Estelle; Legendre, Lucas J.; Cubo, Jorge (January 2016). "Preliminary assessment of bone histology in the extinct elephant bird Aepyornis (Aves, Palaeognathae) from Madagascar". Comptes Rendus Palevol. 15 (1–2): 197–208. Bibcode:2016CRPal..15..197D. doi:10.1016/j.crpv.2015.01.003.

- ^ Balanoff, Amy M.; Rowe, Timothy (12 December 2007). "Osteological description of an embryonic skeleton of the extinct elephant bird, Aepyornis (Palaeognathae: Ratitae)". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 27 (sup4): 1–53. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2007)27[1:ODOAES]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0272-4634. S2CID 85920479.

- ^ Hawkins, A. F. A. & Goodman, S. M. (2003)

- ^ Hansford, J.; Wright, P. C.; Rasoamiaramanana, A.; Pérez, V. R.; Godfrey, L. R.; Errickson, D.; Thompson, T.; Turvey, S. T. (2018). "Early Holocene human presence in Madagascar evidenced by exploitation of avian megafauna" (PDF). Science Advances. 4 (9) eaat6925. Bibcode:2018SciA....4.6925H. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aat6925. PMC 6135541. PMID 30214938.

- ^ Mitchell, Peter (1 October 2020). "Settling Madagascar: When Did People First Colonize the World's Largest Island?". The Journal of Island and Coastal Archaeology. 15 (4): 576–595. doi:10.1080/15564894.2019.1582567. ISSN 1556-4894. S2CID 195555955.

- ^ Hansford, James P.; Lister, Adrian M.; Weston, Eleanor M.; Turvey, Samuel T. (July 2021). "Simultaneous extinction of Madagascar's megaherbivores correlates with late Holocene human-caused landscape transformation". Quaternary Science Reviews. 263 106996. Bibcode:2021QSRv..26306996H. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2021.106996. S2CID 236313083.

Further reading

[edit]- "One minute world news". BBC News. 25 March 2009. Retrieved 26 March 2009.

- Presenter: David Attenborough; Director: Sally Thomson; Producer: Sally Thomson; Executive Producer: Michael Gunton (2 March 2011). BBC-2 Presents: Attenborough and the Giant Egg. BBC. BBC Two.

- Brands, Sheila J. (1989). "The Taxonomicon: Taxon: Order Aepyornithiformes". Zwaag, Netherlands: Universal Taxonomic Services. Archived from the original on 21 April 2008. Retrieved 21 January 2010.

- Brands, Sheila (14 August 2008). "Systema Naturae 2000 / Classification, Genus Aepyornis". Project: The Taxonomicon. Archived from the original on 3 March 2009. Retrieved 4 February 2009.

- Brodkorb, Pierce (1963). "Catalogue of Fossil Birds Part 1 (Archaeopterygiformes through Ardeiformes)". Bulletin of the Florida State Museum, Biological Sciences. 7 (4). Gainesville, FL: University of Florida: 179–293.

- Cooper, A.; Lalueza-Fox, C.; Anderson, S.; Rambaut, A.; Austin, J.; Ward, R. (8 February 2001). "Complete Mitochondrial Genome Sequences of Two Extinct Moas Clarify Ratite Evolution". Nature. 409 (6821): 704–707. Bibcode:2001Natur.409..704C. doi:10.1038/35055536. PMID 11217857. S2CID 4430050.

- Davies, S. J. J. F. (2003). "Elephant birds". In Hutchins, Michael (ed.). Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia, Vol. 8: Birds I Tinamous and Ratites to Hoatzins (2nd ed.). Farmington Hills, MI: Gale Group. pp. 103–104. ISBN 978-0-7876-5784-0.

- Dransfield, John; Beentje, Henk (1995). The Palms of Madagascar. Kew, Victoria, Australia: Royal Botanic Gardens. ISBN 978-0-947643-82-9.

- Flacourt, Etienne de.; Allibert, Claude (2007). Histoire de la grande île de Madagascar (in French). Paris, FR: Karthala. ISBN 978-2-84586-582-2.

- Goodman, Steven M. (1994). "Description of a new species of subfossil eagle from Madagascar: Stephanoaetus (Aves: Falconiformes) from the deposits of Ampasambazimba". Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington (107): 421–428.

- Goodman, S. M.; Rakotozafy, L. M. A. (1997). "Subfossil birds from coastal sites in western and southwestern Madagascar". In Goodman, S. M.; Patterson, B. D. (eds.). Natural Change and Human Impact in Madagascar. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press. pp. 257–279. ISBN 978-1-56098-683-6.

- Hawkins, A. F. A.; Goodman, S. M. (2003). Goodman, S. M.; Benstead, J. P. (eds.). The Natural History of Madagascar. University of Chicago Press. pp. 1026–1029. ISBN 978-0-226-30307-9.

- Hay, W. W.; DeConto, R. M.; Wold, C. N.; Wilson, K. M.; Voigt, S. (1999). "Alternative global Cretaceous paleogeography". In Barrera, E.; Johnson, C. C. (eds.). Evolution of the Cretaceous Ocean Climate System. Boulder, CO: Geological Society of America. pp. 1–47. ISBN 978-0-8137-2332-7.

- LePage, Dennis (2008). "Aepyornithidae". Avibase, the World Bird Database. Retrieved 4 February 2009.

- MacPhee, R. D. E.; Marx, P. A. (1997). "The 40,000 year plague: humans, hyperdisease, and first-contact extinctions". In Goodman, S. M.; Patterson, B. D. (eds.). Natural Change and Human Impact in Madagascar. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press. pp. 169–217.

- Megiser, H. (1623). Warhafftige ... so wol Historische als Chorographische Beschreibung der ... Insul Madagascar, sonsten S. Laurentii genandt (etc.). Leipzig: Groß.

- Mlíkovsky, J. (2003). "Eggs of extinct aepyornithids (Aves: Aepyornithidae) of Madagascar: size and taxonomic identity". Sylvia. 39: 133–138.

- Pearson, Mike Parker; Godden, K. (2002). In search of the Red Slave: Shipwreck and Captivity in Madagascar. Stroud, Gloucestershire: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7509-2938-7.

- van Tuinen, Marcel; Sibley, Charles G.; Hedges, S. Blair (1998). "Phylogeny and Biogeography of Ratite Birds Inferred from DNA Sequences of the Mitochondrial Ribosomal Genes". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 15 (4): 370–376. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025933. PMID 9549088.

- Yoder, Anne D.; Nowak, Michael D. (2006). "Has Vicariance or Dispersal Been the Predominant Biogeographic Force in Madagascar? Only Time Will Tell". Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics. 37: 405–431. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.37.091305.110239.