Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Glossary of partner dance terms

View on Wikipedia

This is a list of dance terms that are not names of dances or types of dances. See List of dances and List of dance style categories for those.

This glossary lists terms used in various types of ballroom partner dances, leaving out terms of highly evolved or specialized dance forms, such as ballet, tap dancing, and square dancing, which have their own elaborate terminology. See also:

Abbreviations

[edit]- 3T – Three Ts

- CBL – Cross-body lead

- CBM – Contra body movement

- CBMP – Contra body movement position

- COG – Center of gravity

- CPB – Center point of balance

- CPP – Counter promenade position

- DC – Diagonally to center

- DW – Diagonally to wall

- IDSF – International DanceSport Federation

- IDTA – International Dance Teachers Association

- ISTD – Imperial Society of Teachers of Dancing

- J&J – Jack and Jill

- LOD – Line of dance

- MPM – Measures per minute

- NFR – No foot rise

- OP – Outside partner or open position

- PP – Promenade position

- Q – Quick

- S – Slow

A–C

[edit]Alignment

[edit]Alignment can mean:

- the directions the feet face in relationship to the room.[1] See Direction of movement.

- the positioning of the body's "building blocks" (head, shoulders, abdomen, hips) in top of each other.[1]

Amalgamation

[edit]A combination of two or more figures;[2] more generally: a sequence of figures that a couple wants to dance.

American Rhythm

[edit]A category of dances in American Style ballroom competitions. It includes cha-cha-cha, rumba, East Coast swing, bolero, and mambo.[1][3] Sometimes it may include samba and West Coast swing.

This category loosely corresponds to the Latin category of International Style ballroom.

American Smooth

[edit]A category of dances in American Style ballroom competitions. It includes waltz, tango, foxtrot, and Viennese waltz.[1] Previously Peabody was also included.

This category loosely corresponds to the Standard category of International Style ballroom. However, Smooth differs from Standard in its inclusion of open and separated figures, whereas Standard makes exclusive use of closed positions.

American Style

[edit]The term describes a particular style of ballroom dances developed in the United States that contrasts with the International Style. In a narrower sense, it denotes the group of dances danced in American Style ballroom competitions. The group consists of two categories: American Smooth and American Rhythm.[1]

Backleading

[edit]In social dancing strongly relying on leading and following, this term means that the follower executes steps without waiting for or contrary to the lead of the leader. This is also called anticipation and usually considered bad dancing habit. An exception would be to avoid a collision with another couple the leader hasn't seen (but this is usually just to stop the leader performing specific steps rather than the follower actively executing steps).

Sometimes this term is used in the meaning of hijacking, which is not exactly the same.

Ballroom

[edit]Body contact

[edit]Body contact is a style of closed position in partner dancing (closed position with body contact); it is also a type of physical connection, mainly of the right-hand sides of the partners' costal arches.

Body flight

[edit]Body flight is a property of many movements in dances such as the waltz and foxtrot. It refers to steps taken with momentum in excess of that necessary to arrive at a point of static balance over the new position, which suggests a carry through to another step in the same direction.[3] Steps in these dances naturally flow one into another, in contrast to the tango and to the Latin and rhythm dances where many steps arrive to a point of static balance.

Body support

[edit]Support of the partner's body is largely avoided in ballroom dancing. The exception would be "lifts" – often featured in some forms of swing dancing, and ballroom showdance presentations, but banned in ordinary ballroom competition and rarely seen in social dancing.

Call

[edit]A call in square dancing is a command by a caller to execute a particular dance figure. In round dancing, calls are called cues. See "Caller" for the explanation of the difference. Voice calls may be complemented by hand signs. See also Voice cue.

Caller

[edit]A caller or a cuer is a person that calls/cues dance figures to be executed in square dances and round dances.

Center

[edit]When indicating a direction of movement during a dance, the term "center" means the direction perpendicular to the line of dance (LOD) pointing towards the center of the room.[3] If one stands facing the LOD, then the center direction is to their left.

The term center may also be used as shorthand for the center point of balance.

Center point of balance

[edit]Together with the center of gravity (COG), the center point of balance (CPB) helps the dancer to better understand and control their movements. CPB differs from the two other centers[clarification needed] in two respects. The exact location of the COG is always well-defined, however it significantly depends on the shape the body assumes. In contrast, the CPB during normal dancing (head up, feet down on the floor) is always at the same place of the dancer's body, although defined in a loose way.[citation needed]

It is said that the CPB is in the general area of the solar plexus for the gentlemen, and navel for the women.[3]

Chassé

[edit]A chassé is a figure of three steps in which the feet are closed on the second step.[2]

Check

[edit]A pronounced discontinuation of movement through the feet.[3] This is created by locking the back of one knee into the front of the other knee. A check position is created in Latin Ballroom dances such as rumba and cha-cha-cha, as well as in International Standard Ballroom dances such as quickstep locks.

Closed dance figure

[edit]The term has at least two meanings: regarding dance position and regarding footwork.

- A figure performed in closed position.

- A figure in which at the last step the moving foot closes to rest at the support foot.[1] Examples are box step in American Style waltz or natural turn in International Style waltz.

Closed position

[edit]The ordinary position of ballroom dancing in which the partners face each other with their bodies approximately parallel. In Standard and Smooth the bodies are also offset about a half body width such that each person has their partner on their right side, with their left side somewhat unobstructed;[3] in tango, the offset is somewhat larger. Contrast promenade position and open position.

Compression

[edit]The term has several meanings.

- Compression is a type of physical connection, opposite to leverage, in which the dance partners lean together while being connected. In other words, a stress exists at the point(s) of contact directed towards the contact point(s) of the dance partner.[4] The term is frequently used, e.g., in the swing dance community.

- Compression is lowering the body by bending the knees in a preparation for a step.[3] The term is mostly used in describing the rises and falls technique of ballroom dances of Standard (International style) and Smooth (American style) categories: waltzes, tangos, foxtrots.

- Compression is a hip action in Latin dances.

- An action to achieve a graceful sway.

Connection

[edit]A means of communication between dancers in the couple. Physical and visual types of connection are distinguished.[3] Physical connection, sometimes referred to as resistance or tone, involves slightly tensing the upper-body muscles, often in the context of a frame, thus enabling leader to communicate intentions to follower. See compression and tension, two basic associated actions/reactions.

Contra body movement

[edit]Refers to the action of the body in turning figures; turning the opposite hip and shoulder towards the direction of the moving foot.[5][6]

Contra body movement position

[edit]Contra body movement position occurs when the moving foot is brought across (behind or in front) the standing foot without the body turning.[7] Applies to every step taken outside partner; occurs frequently in tango and in all promenade figures.

Counter promenade position

[edit]In ballroom dances, the dance couple moves (or intends to move) sidewise to the leader's right while the bodies form a V-shape, with leader's left and follower's right sides are closer than the leader's right and follower's left.[8] In other dances, there are other definitions.

Cuban hip motion

[edit]Cue

[edit]A signal to execute a dance figure.[3] See Call and Voice cue.

D–J

[edit]Dance formation

[edit]Dance move

[edit]Dance pattern

[edit]Dancesport

[edit]Dancesport is an official term to denote dance as competitive, sport activity.[1]

Dance step

[edit]For one meaning, see Dance move, for another one, see Step. See also Glossary of dance steps.

Direction of movement

[edit]Direction of step

[edit]Direction of turn

[edit]Fallaway

[edit]Both dance partners take (at least) a step backwards into promenade position.[3]

Figure

[edit]A completed set of steps.[2] More explicitly: a small sequence of steps comprising a meaningful gestalt, and given a name, for example whisk or spin turn.

Follower

[edit]Footwork

[edit]In a wider sense, the term footwork describes dance technique aspects related to feet: foot position and foot action.[3]

In a narrow sense, e.g., in descriptions of ballroom dance figures, the term refers to the behavior of the foot when it is in contact with the floor. In particular, it describes which part of the foot is in contact with the floor: ball, heel, flat, toe, high toe, inside/outside edge, etc.[3] In the Smooth and Standard dances, it is common for the body weight to progress through multiple parts of the foot during the course of a step. Customarily, parts of the foot reached only after the other foot has passed to begin a new step are implied but not explicitly mentioned.

Formation

[edit]- A formation or dance formation is a team of dance couples.[1]

- Formation of a dance team is the specification of

- positions of dancers or dance couples on the floor relative to each other and

- directions the dancers face or move with respect to others.

Formation dance

[edit]Formation dance is a choreographed dance of a team of couples, e.g., ballroom sequence or ballroom formation dance/team.

Full weight

[edit]Full weight or full-weight transfer means that at the end of the step the dancer's center of gravity is directly over the support foot. A simple test for a full weight transfer is that you can freely lift the second foot off the floor.

Frame

[edit]Dance frames are the positions of the upper bodies of the dancers (hands, arms, shoulders, neck, head, and upper torso).[3] A strong frame is where your arms and upper body are held firmly in place without relying on your partner to maintain your frame nor applying force that would move your partner or your partner's frame. In swing and blues dances, the frame is a dancer's body shape, which provides connection with the partner and conveys intended movement.[4]

Major types of dance frames are Latin, smooth, and swing.

Guapacha

[edit]Guapacha timing is an alternative rhythm of various basic cha-cha steps that are normally counted "<1>, 2, 3, cha-cha-1" whereas "cha-cha-1" is counted musically "4-&-1". In Guapacha, the step that normally occurs on count "2" is delayed an extra half-beat, to the "&" of 2, making the new count "<1>, <hold>-&-3, 4-&-1".[1]

Handhold

[edit]Handhold is an element of dance connection: it is a way the partners hold each other by hands.

Heel lead

[edit]Landing on the heel of the foot in motion during a step before putting weight on the remainder of the foot. As in normal walking, much of the swing of the foot is accomplished with its midpart closest to the floor, emphasis shifting to the heel only as the final placement is neared.

Heel turn

[edit]A heel turn is an action danced by the partner on the inside of turn in certain figures in Standard or Smooth. During the course of rotation, the dancer's weight moves from toe to heel of one foot while the other foot swings to close to it, then forward from heel towards the toe of the just closed foot.[3] Follower's heel turns feature body rise coincident with the first step, which leads her foot to close next to the standing one rather than swing past. In contrast, when the leader is dancing a heel turn the rise is delayed until the conclusion of the turn, as he can better lead the amount of turn from a more grounded position. The heel turn is distinguished from other members of the family of heel pull actions which do not require complete closure of the feet. Follower's heel turns are commonly found in the double reverse spin and the open or closed telemark, and the natural and reverse turns of international style foxtrot, while leader's heel turns form the basis of the open or closed impetus.

Hijacking

[edit]In social dancing strongly reliant on leading and following, hijacking means temporary assuming the leading role by the follower. Also known as stealing the lead. Contrast backleading.

International Latin

[edit]International Latin is category of dances in International Style ballroom competitions. It includes samba, cha-cha-cha, rumba, pasodoble, and jive.[1]

International Standard

[edit]A category of dances in International Style ballroom competitions. Sometimes in the context of competitions it is called Ballroom or International Ballroom, confusing as it might be. (In England, the term "Modern" is often used, which should not be confused with modern dance that derives from ballet technique) It includes waltz (formerly called "slow waltz"), tango, foxtrot, quickstep, and Viennese waltz.[1] This category loosely corresponds to the Smooth category of American Style ballroom.

International Style

[edit]The term describes a particular style of ballroom dances that contrasts with American Style. In a narrower sense, it denotes the group of dances danced in International Style ballroom competitions. The group consists of two categories: Standard and Latin.[1]

Jack and Jill

[edit]Jack and Jill (J&J) is a format of competition in partner dancing, where the competing couples are the result of random matching of leaders and followers.[9] Rules of matching vary. The name comes from the popular English nursery rhyme, "Jack and Jill". In venues with same-gender dance partners, the ambiguous names "Pat and Chris" have been used, or event could be called "Mix and Match".

In dance competitions J&J is included as a separate division (or divisions, with additional gradations). J&J is popular at swing conventions, as well as at ballroom dance competitions in the United States.

L–R

[edit]Latin

[edit]As applied to dances, Latin dance is any type of social dance of Latin American origin.

Latin hip motion

[edit]A characteristic type of hip motion found in the technique of performing a step in Latin and Rhythm dances.[1] Although most visible in the hips, much of the effect is created through the action of the feet and knees. Sometimes it is also called Cuban hip motion, although because of the divergence in dance technique between American Rhythm and International Latin some prefer to distinguish the two, with the term "Latin motion" reserved for International Style, while the "Cuban motion" reserved for American Style and Club Latin dances. The most notable distinction (in a simplified description) is that in the International Style "Latin motion" the straightening of the knee happens before the full weight transfer, while in the "Cuban motion" the straightening of the knee happens after the full weight transfer. As a result, the Cuban hip motion results in a more fluid leg movement, whereas the Latin hip motion results in a more staccato leg movement.

Leader

[edit]Leading and following

[edit]Lead stealing

[edit]Leverage

[edit]The term describes type of physical connection, opposite to compression, in which the dance partners lean away from each other while being connected. In other words, a stress exists at the point(s) of contact directed away from the contact point(s) of the dance partner. Predominantly used in the swing dance community.[4] See also tension.

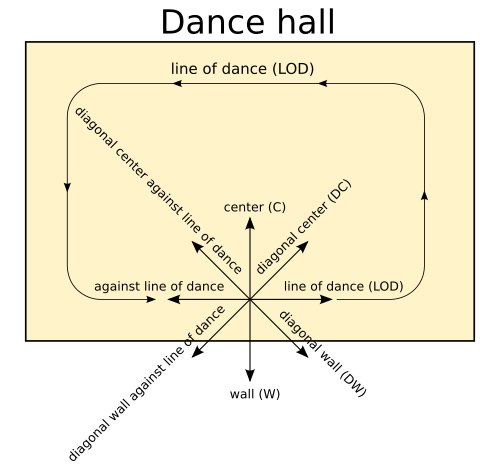

Line of dance

[edit]

Line of dance (LOD or LoD) is conceptually a path along and generally parallel to the edge of the dance floor in the counterclockwise direction. To help avoid collisions, it is agreed that in travelling dances dancers should proceed along the line of dance.[1]

Line of dance is a useful line of reference when describing the directions of steps taken, e.g., "facing LOD", "backing [or reverse] LOD". See also center, wall. Reference to the direction of movement is based on the direction faced by the leader rather than the follower.

Line of foot

[edit]An imaginary straight line passing through the foot in the heel-toe direction.

Measures per minute

[edit]Measures per minute, or MPM, refers to the tempo of the music according to the number of measures or bars occurring in one minute of music. This can vary from as low as 25–27 MPM for international style rumba to as fast as 58–60 MPM for international style Viennese waltz.

Moving foot

[edit]The foot that is in action (tap, ronde, etc.) while most or all of the body's weight is being supported by the standing foot. Compare Supporting foot.

Musicality

[edit]New Vogue

[edit]No foot rise

[edit]In descriptions of the footwork of step patterns the abbreviation NFR stands for no foot rise (or no foot-rise) and means that the heel of the support foot remains in contact with the floor until the weight is transferred onto the other foot.[1] The rise is felt in body (i.e. the torso) and legs only, not in the feet.

Open dance figure

[edit]The term has at least two meanings: regarding dance position and regarding footwork.

- A figure performed in open position.

- A figure in which during the last step the moving foot passes the support foot.[1] Examples are the feather step in foxtrot or the open reverse turn, e.g. in tango.

Open position

[edit]Open position is any dance position in couple dances, in which the partners stand apart in contrast to closed position. They may face inwards or outwards, and hold one or both hands or stand independently.

Outside partner position

[edit]A step into outside partner position occurs when the moving foot of the forward travelling partner moves on a track outside of their partner's standing foot when it would ordinarily move on a track aimed between their partner's feet. Due to the offset of the hold, this generally applies to a step with the right foot. (The term left side outside is often used for the rare occurrences when the left foot crosses to pass outside, as in the Hover cross). Steps into outside partner position are also required to be in contra body movement position, and are often preceded by a step with a strong side lead. The term "inline" is occasionally used when it is necessary to clarify that an outside partner position is not involved.

Pat and Chris

[edit]Physical connection, physical lead

[edit]A dance connection by means of physical contact. Types of physical connection are body contact, compression, leverage.

Pinched shoulder

[edit]Pinched shoulder is the position seen when promenade position is incorrectly danced with an outward rotation of the upper bodies, rather than a rotational stretch in each body. It is characterized by one or both partners having their trailing elbow behind the line of their shoulders, with a resulting break in the arm line at the trailing shoulder.

Progressive dance

[edit]Promenade position

[edit]The promenade position is described differently in various dance categories.

In ballroom dances their common trait is that the dance couple moves (or intends to move) essentially sidewise to the leader's left while partners nearly face each other, with the leader's right side of the body and the follower's left side of the body are closer than the respective opposite sides (forming a V-shape when looking from above). Steps of both partners are basically sidewise or diagonally forward with respect to their bodies. Normally the dancers look in the direction of the intended movement.[3]

In square dances it is a close side-by-side position in various handholds with the general intention to move together forward, "in promenade".

In American tango, the partners shift their shoulders, hips and heads to a variable degree less and up to 90 to that of their original position, while their feet: man's left; lady's right are rotated respectively leftward and rightward to make a "V" (to the left/right). This exact position is also called semi-open in some dance books, by some authors and teachers, especially in American Smooth Ballroom dance.[10] The shift in Argentine/salon style tango is less pronounced and more individualized: the hold similarly variable but usually very close especially in the upper body, less in the hips.[11] In some swing dances (East Coast, triple-count, country, or single-count), the feet are more opened/rotated in their respective directions to lie parallel to each other and exactly perpendicular to their original Closed position placement.[12] The intention, is for the position to anticipate a change in direction of movement, to direct each partner of the couple/partnership, and to lead the follower to step in the direction of the rotation between their bodies; similarly for the counter promenade position.

Replace

[edit]In brief descriptions of dance figures, replace means replacing the weight to the previous support foot while keeping it in place. For example, a "rock back" figure may be described as "step back, replace". Notice that it doesn't require to "replace" the moving foot to the place from where it come in the previous step.

Rhythm

[edit]- See American Rhythm.

- See Rhythm.

Rise and fall

[edit]Rises and falls refer to the body ascending and descending by use of feet, ankles, and legs, to create dynamic movement.[1]

S–Z

[edit]Shadow position

[edit]Both partners face the same general direction, one of them (the man) behind and slightly shifted leftwards ("in the shadow").[3] Handholds vary. Variants: sweetheart position, cuddle position.

Side lead

[edit]A body position or action during a step, sometimes also called same side lead. Side-leading refers to a movement during which the side of the body corresponding to the moving foot is consistently in advance[1] as a result of a previous contra body movement or body turns less action. A step with side lead will often precede or follow a step of the opposite foot taken into contra body movement position (in which the leading side is that opposite the moving foot) without requiring intervening rotation of the body.

Due to the offset position of the partners in the hold, a left side lead may be quite pronounced whereas a right side lead will be more subtle if taken in closed position.

Slot

[edit]In slotted dances, the dance slot is an imaginary narrow rectangle along which the follower moves back and forth with respect to the leader, who is more or less stationary.[1] As a rule, the leader mostly stays in the slot as well, leaving it only to give way for the follower to pass him. Some slots are fixed, some can rotate, some are only from close hold to open hold with one arm, or double from one side of the man to his full reach on the other (as in hustle), depending on the dance floor space available and the specific dance. The leader in social and performance/exhibition dancing is more free to step out from the slot, more in some dances, and dance styles (such as hustle and salsa), than in others.

Slotted dance

[edit]A dance style in which the couple's movements are generally confined to a slot. The most typical slotted dance is west coast swing.[3] Some other dances, e.g., hustle and salsa, may be danced in slotted style. Compare spot dance, travelling dance.

Smooth

[edit]Spot dance

[edit]A dance that is generally danced in a restricted area of the dance floor. Examples are rumba, salsa, east coast swing. Compare travelling dance, slotted dance.

Spotting

[edit]A technique used during turns. The dancer chooses a reference point (such as their partner or a distant point along the line of travel) and focuses on it as long as possible.[1] When during the turn it is no longer possible to see it, the head flips as fast as possible to "spot" the reference point again. This technique guides the body during the turn, makes it easier to determine when to stop turning, and helps prevent dizziness. It must be done by rotating the head as close to perfectly in the horizontal plane as possible so as not to defeat the purpose of minimizing dizziness in those so predisposed. The most common spotting is 180° to and away from one's partner, or the line of dance (LOD) and a full 360° from the original spot, be it LOD, outside line of dance (OLOD), or toward or away from one's partner, a wall for example. It can be done in apart/free position or less frequently in closed position.

Standard

[edit]Stationary dance

[edit]Stealing the lead

[edit]In social dancing strongly reliant on leading and following, stealing the lead means temporary assuming the leading role by the follower. Also known as hijacking. Contrast backleading.

Step

[edit]- In a strict sense, a step, or a footstep, is a single move of one foot, usually involving full or partial weight transfer to the moving foot.[1] However foot actions, such as tap, kick, etc., are also sometimes called "steps". For example, in a description: "step forward, replace, together" all three actions are steps.

- Sometimes it is important to define the exact limits of one (foot)step, i.e., exactly when it begins and ends. In describing the detailed technique in Standard and Smooth dances (waltz, tango,...) it is agreed that in figures where the moving foot doesn't stop at the support foot a step begins (and the previous step ends) at the moment when the moving foot passes the support foot. Notice that according to this agreement such steps do not begin and end precisely at the "counts" 1, 2, etc. which normally match musical beats.

- In a broader sense, step means dance step,[1] i.e., a dance figure, for example: basic step, triple step.

Standing foot

[edit]Same as Supporting foot.

Supporting foot

[edit]It is also called support foot or standing foot, a foot which bears the full or nearly full weight while the other foot does some action (step, tap, ronde, etc.). Compare moving foot.

Sway

[edit]

This image also illustrates a strong top line in International Standard dances.

The term sway has a specific meaning in the technique of ballroom dancing. Basically, it describes a body position in which its upper part gracefully deflects from the vertical. The direction of sway is usually away from the standing foot and the direction of movement.[1]

Syncopation

[edit]In dancing, the term syncopation has two meanings. The first one is similar to the musical terminology: stepping on an unstressed musical beat.[1][3] The second one is making more (and/or different) steps than required by the standard description of a figure,[1] to address more rhythmical nuances of the music. The latter usage is considered incorrect by many dance instructors, but it is still in circulation, a better term lacking.[citation needed]

Tension

[edit]Describes a physical connection, opposite to compression, in which a stress exists at the point(s) of contact directed away from the contact point(s) between partners. People frequently resort to describing the actions as "push" (compression, towards partner) and "pull" (tension, away from partner) to get the idea across. See also leverage.

Three Ts

[edit]Technique, timing, and teamwork. The criteria for evaluation of dance mastery in the swing dancing community.

Timing

[edit]The relation of the elements of a dance step or dance figure with respect to musical timing: bars and beats. Also the synchronizing of movements between the dance partners, or between the parts of a dancer's body.[1]

Toe lead

[edit]Landing on the toe of the foot in motion during a step before putting weight on the remainder of the foot.

Top line

[edit]The top line is the way dancers hold their head, neck, shoulders, arms, hands, and upper back.[3]

Tracking, track of foot

[edit]The trajectory of the moving foot visualized as a narrow imaginary track, forward and backward of the foot rather than a line.[1] For the standing foot, its track is determined by its current orientation on the floor which may be noted on the inside of turns where the feet often point in differing directions.

Travelling (progressive) dance

[edit]A dance that significantly travels over the dance floor, generally in the direction of the line of dance. Examples are waltz, foxtrot, polka, samba, Argentine tango. Compare spot dance, slotted dance.

Visual connection, visual lead

[edit]A dance connection by means of visual awareness of partners in a couple.[3] Visual connection by no means should replace the physical connection, and some consider it to be an inferior form of connection. However it does have its proper usages. Most important are the coordination of styles (arms, etc.) and when dancing without physical contact. An important example of the latter is spotting the partner during turns, especially free spins.

This type of connection is essential for "shine position patterns", commonly found in Latin dances like the cha-cha-cha, mambo, and salsa as well as "side by side position patterns".

Voice cue

[edit]Voice cues help match rhythmic patterns of steps (or other moves) with the music. There are different types of voice cues.

- The most common example is the usage of "quick" and "slow" words: "quick-quick-slow" (pronounced as "quick quick slo-o-o-ow") immediately tells you that the third step takes twice the time of the first one (and of the second one).

- Some East Coast Swing instructors cue the basic step as "shuf-fle-STEP, shuf-fle-STEP, rock BACK", to indicate both the rhythmic pattern of the figure (1&2, 3&4, 5, 6) and the syncopated character of swing music: every second syllable is stressed.

- Still another example: the box step of American-style rumba may be cued as "forward-...-side-together, back-...-side-together", to indicate the directions of (leader's) steps and their timing.

- Finally, for more advanced dancers voice cues are actually names of dance figures and standard variations:

- "Two walks, link, closed promenade" (tango).

- "Open Telemark, natural fallaway, whisk, quick wing" (waltz).

- "Dile que no!... setenta!... Dame dos con una!..." (Spanish, used in salsa rueda)

Cues are an important element of round dances.[3] In square dances they are called calls and called by a caller.

Wall

[edit]When indicating a direction of movement during a dance, the term "wall" means the direction perpendicular to the line of dance (LOD) pointing towards the wall of the room (possibly imaginary). If one stands facing the LOD, then the wall direction is to their right.[13]

Weight transfer

[edit]See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa "Dance dictionary". BallroomDancers.com. Retrieved 2020-05-04.

- ^ a b c Moore, Alex (1986). "Definitions of terms". Ballroom Dancing (9th ed.). London: Adam & Charles Black. p. 30.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u "Glossary of Round Dance Terms" (PDF). International Choreographed Ballroom Dance Association. Retrieved 2020-06-04.

- ^ a b c DeMers, Joseph Daniel (2013). "Frame matching and ΔPTED: a framework for teaching Swing and Blues dance partner connection". Research in Dance Education. 14 (1): 71–80. doi:10.1080/14647893.2012.688943. S2CID 144054392.

- ^ Moore, Alex (1986). "Contrary body movement". Ballroom Dancing (9th ed.). London: Adam & Charles Black. p. 15.

- ^ Silvester, Victor (1977). "Contrary body movement". Modern ballroom dancing: history & practice (9th ed.). London: Paul. p. 81.

- ^ Moore, Alex (1986). "Contrary body movement position". Ballroom Dancing (9th ed.). London: Adam & Charles Black. p. 17.

- ^ Richard M. Stephenson; Richard Montgomery Stephenson (1992). The Complete Book of Ballroom Dancing. Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-42416-5.

- ^ Blair, Skippy (1994). Dance Terminology Notebook. Altera. pp. 37–38. ISBN 0-932980-11-2.

- ^ Harris, Jane A.; Pittman, Anne M.; Waller, Marlys S.; Dark, Cathy L. (2002). Social Dance from Dance A While. Benjamin Cummings. ISBN 978-0805353662. See illustrations of positions and related descriptions.

- ^ Bottomer, Paul (1990). Argentine Tango. Sounds Sensational. ISBN 978-0951724309.

- ^ Monte, John; Lawrence, Bobbie; Astaire, Fred (1978). The Fred Astaire Dance Book. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0671230647.

- ^ "Alignment diagram". DanceCentral.info. Archived from the original on 2020-04-28. Retrieved 2020-04-30.

External links

[edit]- Streetswing.com large information base about more than thousand dances.