Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

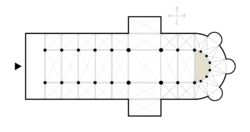

In architecture, an apse (pl.: apses; from Latin absis, 'arch, vault'; from Ancient Greek ἀψίς, apsis, 'arch'; sometimes written apsis; pl.: apsides) is a semicircular recess covered with a hemispherical vault or semi-dome, also known as an exedra. In Byzantine, Romanesque, and Gothic Christian church (including cathedral and abbey) architecture, the term is applied to a semi-circular or polygonal termination of the main building at the liturgical east end (where the altar is), regardless of the shape of the roof, which may be flat, sloping, domed, or hemispherical. Smaller apses are found elsewhere, especially in shrines.[1]

Definition

[edit]An apse is a semicircular recess, often covered with a hemispherical vault. Commonly, the apse of a church, cathedral or basilica is the semicircular or polygonal termination to the choir or sanctuary, or sometimes at the end of an aisle.

Smaller apses are sometimes built in other parts of the church, especially for reliquaries or shrines of saints.[citation needed]

History

[edit]The domed apse became a standard part of the church plan in the early Christian era.[2]

Related features

[edit]In the Eastern Orthodox Church tradition, the south apse is known as the diaconicon and the north apse as the prothesis. Various ecclesiastical features of which the apse may form part are drawn together here.

Chancel

[edit]The chancel (or sanctuary), directly to the east beyond the choir, contains the high altar, where there is one (compare communion table). This area is reserved for the clergy, and was therefore formerly called the "presbytery", from Greek presbuteros, "elder", [citation needed] or in older and Catholic usage "priest".[3]

Chevet-apse chapels

[edit]Semi-circular choirs, first developed in the East, which came into use in France in 470.[4] By the onset of the 13th century, they had been augmented with radiating apse chapels outside the choir aisle, the entire structure of apse, choir and radiating chapels coming to be known as the chevet (French, "headpiece").[5]

Gallery

[edit]-

Triple apse of Basilica di Santa Giulia, northern Italy

-

East end of the abbey church of Saint-Ouen, showing the chevet, Rouen, Seine-Maritime, France

-

A chevet apse vault, Toulouse, France

-

Apsed chancel of St Mary's Church, West Dean, Wiltshire, England

-

The decorated apse of the Cathedral of Monreale, Sicily

-

The apse of Manila Cathedral, Philippines

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception: Floor Plan". NationalShrine.com. Archived from the original on 9 August 2017. Retrieved 27 August 2016.

- ^ "Apse". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 10 July 2012.

- ^ "Where in the New Testament are Priests Mentioned". Catholic Answers. Catholic Answers. Retrieved 1 September 2018.

- ^ Moss, Henry, The Birth of the Middle Ages 395-814, Clarendon Press, 1935

- ^ "Chevet", Encyclopædia Britannica

- Joseph Nechvatal, "Immersive Excess in the Apse of Lascaux", Technonoetic Arts 3, no. 3, 2005.

External links

[edit]- Spiers, Richard Phené (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 2 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 231–232. This has a detailed description of examples in the early church.

Definition and Etymology

Definition

In architecture, an apse is defined as a semicircular or polygonal recess projecting from a building's interior wall, typically located at the eastern end of a church's choir or nave.[1] This element, often adopted from Roman basilicas, serves as a key feature in religious structures.[3] The primary function of the apse in religious architecture is to house the main altar, creating a symbolic sacred space that directs congregational attention during liturgical ceremonies.[1] It emphasizes the altar as the focal point for worship, enhancing the ritual experience through its prominent positioning.[5] Geometrically, the apse features a curved plan, frequently capped by a domed or semi-domed ceiling known as the conch, which provides a vaulted enclosure.[5] It integrates with the main body of the structure through an opening framed by a triumphal arch, allowing visual and spatial continuity between the recess and the nave or choir.[6]Etymology

The term "apse" in architecture derives from the Latin apsis, meaning "arch" or "vault," which itself originates from the Ancient Greek ἅψις (hápsis), denoting a "loop," "arch," or "fastening." The Greek root stems from the verb ἅπτω (háptō), "to fasten together," and initially referred to mechanical elements like the felloe of a wheel or the loop of a bow, emphasizing curved or joined structures.[7] This foundational meaning captured the idea of arcs connecting to form a circle, a concept that transitioned from everyday objects to more abstract applications.[8] In Roman contexts, apsis retained its association with vaulted or arched forms, adapting the Greek term to describe structural features in buildings, such as semicircular recesses. The semantic shift from a general "loop" or "bow" in astronomy—where it denoted orbital points known as apsides—to an architectural "recess" or "niche" occurred through this Latin usage, highlighting the term's evolution from celestial to built environments. By the medieval period, the word influenced Romance languages, appearing as abside in Old French, which contributed to its broader dissemination in European architectural discourse.[7][9] The term entered English primarily through Latin scholarly texts, with "apsis" first documented in architectural references around 1706, before "apse" became the standard form in 1846, reflecting a direct borrowing suited to describing church extensions. This linguistic path underscores how the word's curved connotation persisted, bridging ancient technical origins to modern architectural terminology.[7]Historical Development

Ancient Origins

The apse, as a semicircular or curved recess, traces its architectural precedents to ancient Greek designs, where exedrae served as outdoor seating areas or niches integrated into stoas and temples. These curved elements, often found in public spaces like the Stoa of Attalos in Athens, provided shaded benches for philosophical discussions or gatherings, influencing later Roman adaptations by emphasizing functional enclosure within larger structures. In Roman architecture, the apse evolved into a prominent feature of basilicas, public buildings used for legal proceedings, commerce, and administration, emerging prominently from the 1st century BCE. Semicircular exedrae at the ends of these rectangular halls accommodated magistrates' tribunals, as seen in the Basilica Aemilia, constructed in 179 BCE in the Roman Forum, where a recess at one end housed the judge's seat amid column-divided naves. Similarly, the Basilica of Constantine, completed in the early 4th century CE, featured a grand semicircular apse at its western end, spanning a vast interior space for imperial audiences and trials.[10][11] Roman engineers achieved the stability of these apses through innovative use of concrete vaults and arches, which distributed weight evenly to prevent collapse under the curved forms' thrust. The opus caementicium concrete, reinforced with volcanic ash for durability, allowed for the construction of hemispherical vaults over the apse, while voussoir arches along the nave transferred loads to sturdy piers, enabling larger, enclosed civic spaces without excessive internal supports. This engineering prowess ensured the apse's role in hosting authoritative functions, such as seating for presiding officials.[12][13]Medieval Evolution

Following the Edict of Milan in 313 CE, early Christians rapidly adopted the Roman basilica form for their churches, integrating the apse as a semicircular eastern termination to house the altar and emphasize clerical authority. This adaptation transformed the apse from its secular Roman judicial role into a sacred space for liturgical focus, often screened by a triumphal arch to separate the congregation from the sanctuary. A prime example is Old St. Peter's Basilica in Rome, commissioned by Emperor Constantine around 324 CE, where the apse's mosaics and arch underscored the church's imperial patronage and apostolic significance.[3][14] In the Romanesque period from the 10th to 12th centuries, apses evolved to support heavier stone construction amid growing monastic and pilgrimage demands, featuring thicker walls and barrel vaults for structural stability against lateral thrust. These vaults, often illuminated by small clerestory windows, allowed for enclosed, fire-resistant interiors while maintaining the apse's role as the liturgical core. Cluny Abbey in France, rebuilt as Cluny III starting in the late 11th century, exemplifies this with its ambulatory encircling the apse and radiating chapels, facilitating relic veneration and processions in a vast basilica that symbolized Cluniac reform's spiritual ambition.[15] The Gothic era, spanning the 12th to 16th centuries, introduced ribbed vaults and flying buttresses, enabling apses to rise taller and lighter with thinner walls, vast windows, and enhanced verticality to evoke divine aspiration. These innovations distributed weight externally, freeing interior space for ornate tracery and stained glass that bathed the apse in light, reinforcing its symbolic role as a heavenly threshold. Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris, begun in 1163, demonstrates this in its apse with five radiating chapels, where flying buttresses—added progressively through the 13th century—supported soaring ribbed vaults, achieving unprecedented height and luminosity in the choir area.[16] Medieval apse designs also diverged regionally, with Eastern Orthodox architecture crowning apses under domes to symbolize the vault of heaven descending to earth, as seen in Byzantine-influenced churches where the dome's Pantocrator icon linked the divine realm to the earthly liturgy below. In contrast, Western Latin Rite churches typically arranged the apse within a cruciform plan resembling a Latin cross, prioritizing longitudinal processions from nave to sanctuary to reflect the faith's narrative progression.[17][18]Post-Medieval Variations

During the Renaissance, architects revived classical semicircular apse forms, adapting them with humanist proportions that emphasized harmony and mathematical precision inspired by ancient Roman basilicas. Donato Bramante's initial design for St. Peter's Basilica in Rome (1506) exemplified this revival, proposing a centralized Greek cross plan enclosed in a square, where semicircular elements at the eastern end echoed the Pantheon’s dome and apse-like recesses to symbolize eternal perfection.[19][14] In the Baroque period of the 17th and 18th centuries, apses evolved into dynamic spaces with exaggerated curves, stucco work, and illusory frescoes to heighten emotional impact and counter Reformation fervor. The apse of Il Gesù in Rome (completed 1584, with Baroque embellishments in the late 16th and 17th centuries) featured dramatic frescoes and sculpted elements by artists like Giovanni Battista Gaulli, creating an immersive illusion of heavenly extension beyond the architecture.[20][21] From the 19th century onward, apsidal forms appeared in secular architecture, particularly in legislative chambers designed for acoustic clarity and symbolic grandeur, diverging from ecclesiastical roots. The U.S. Capitol's House of Representatives chamber (completed 1857), with its semicircular hemicycle facing the Speaker's rostrum, drew on classical apse motifs to evoke ancient Roman assemblies while optimizing sound projection for debates.[22] The global spread of apse variations occurred through colonial architecture, where European forms merged with local materials and contexts in Latin American missions. Spanish missions like San Xavier del Bac in Arizona (1797) incorporated semicircular apsides in adobe structures, adapting Renaissance and Baroque proportions to arid environments while serving as focal points for worship.[23] In Islamic-influenced regions, the mihrab functioned as an apse-like niche, directing prayer toward Mecca with ornate semicircular arches that paralleled Christian apses in spatial emphasis, as seen in early mosques like the Great Mosque of Córdoba (8th-10th centuries), influencing hybrid designs in colonial Hispano-America.[24]Architectural Features

Structural Components

The apse integrates structurally with the nave via a continuous foundation, typically formed from compacted stone rubble and lime mortar to distribute loads evenly across the basilica's longitudinal axis and prevent differential settlement. This shared base, often shallow at about three feet deep in Roman examples, allows seamless extension from the rectangular nave to the curved apse termination, maintaining overall stability. The triumphal arch, a robust arched opening at the nave-apse junction, serves as a primary load-bearing element, framing the transition and supporting the weight of the overlying vaults while channeling forces downward to the foundations. The vaulted conch, the apse's crowning semi-dome, is constructed from layered brick, cut stone, or poured concrete, creating a self-supporting hemispherical shell that encloses the space and resists outward thrust through its curved geometry. In domed apses, particularly in Byzantine and later traditions, load-bearing transitions from square to circular plans employ pendentives or squinches to bridge geometric disparities and sustain the dome's weight. Pendentives consist of concave triangular vaults that form the upper corners of a square bay, smoothly converting it to a circular drum for the dome's base, as exemplified in structures like Hagia Sophia. Squinches, alternatively, use corbeled arches or small vaults inset at the corners to approximate an octagonal support, distributing loads more discretely in polygonal apses. These elements ensure structural equilibrium by converting vertical pressures into compressive forces along the curved surfaces. Materials for apse construction evolved significantly over time, reflecting advances in engineering and resource availability. Roman builders relied on opus caementicium, a hydraulic concrete mixed with pozzolana ash, volcanic aggregates, and lime, which hardened underwater and enabled monolithic vaulting in apses of basilicas like Old St. Peter's. By the medieval period, ashlar masonry—precisely squared stone blocks laid in regular courses with thin mortar joints—became standard for apse walls, arches, and vaults, offering superior precision and durability as seen in Romanesque churches such as the Basilica of San Isidoro in León. In Gothic architecture, fine-grained limestone predominated for its workability and compressive strength, often incorporating embedded iron reinforcements, such as tie rods and anchors, to counter tensile stresses in ambitious ribbed vaults and flying buttresses supporting apse complexes. The apse's curved walls inherently enhance acoustics by reflecting and focusing sound waves from the altar toward the nave, promoting even projection of chants and spoken liturgy without excessive diffusion. This parabolic form acts like a natural amplifier, minimizing echoes while sustaining reverberation suitable for polyphonic music. Clerestory windows, narrow openings high in the conch or flanking walls, admit natural daylight to illuminate the apse interior, creating a luminous focal point that highlights structural details and integrates with the overall basilica lighting scheme derived from Roman precedents.Decorative and Functional Aspects

Apses in ecclesiastical architecture have long served decorative purposes that enhance the spiritual ambiance of sacred spaces, often transforming the curved conch—the vaulted semicircular ceiling—into a visual representation of the divine realm. In early Christian basilicas, particularly those in Ravenna from the 6th century, intricate mosaics adorned the apse walls and conch, depicting Christ in majesty or key biblical scenes such as the Transfiguration to evoke a heavenly illusion and draw worshippers' gaze upward toward eternity.[25][26] These mosaics, composed of tesserae in gold and vibrant colors, created a shimmering effect that mimicked celestial light, reinforcing the apse as a portal to the divine. Later traditions incorporated frescoes on the apse surfaces, as seen in medieval Roman churches, where painted scenes of saints and apostles filled the conch to symbolize communal unity in worship.[27] Altarpieces, often placed at the apse's focal point, further amplified this aesthetic role; Renaissance examples, such as those in Venetian churches, integrated painted panels with architectural frames to extend the illusion of depth and sanctity into the sanctuary.[28] Symbolically, the apse embodies the "head" of the ecclesiastical body, mirroring the church as an extension of Christ's presence and serving as the liturgical climax during processions that culminate in the eastward-oriented space.[29] This eastern orientation, a convention rooted in early Christian design, aligns the apse with the rising sun to symbolize resurrection and Christ's return, directing the congregation's prayers toward eschatological hope.[29] As the focal point for rituals, the apse underscores hierarchical and communal devotion, with its form evoking the divine throne room described in scriptural visions.[30] Functionally, apses incorporated practical elements to support clerical activities and veneration. In early basilicas, the synthronon—a tiered, semicircular bench carved into the apse walls—provided tiered seating for clergy, allowing bishops and presbyters to preside over liturgies while visible to the assembly.[31] The cathedra, or bishop's throne, was centrally integrated into the apse, often elevated at the synthronon's apex to signify authority and continuity with apostolic tradition.[32] Relics of saints were frequently enshrined within or beneath the apse altar, transforming the space into a site of pilgrimage and intercession, as evidenced in late antique Roman churches where martyr remains were incorporated to sanctify the enclosure.[33] The apse's curved geometry also contributes to acoustic functionality, with its surfaces designed to project and amplify clerical voices and choral chants across the nave. In basilicas like St. Mark's in Venice, the apse's vaulted conch enhances reverberation, supporting polyphonic liturgies and creating an immersive auditory experience that complements visual splendor.[34] This acoustic amplification, a byproduct of the semicircular form, influences musical practices by fostering resonance that elevates the sense of divine presence during worship.[35]Types and Variations

Semicircular Apse

The semicircular apse consists of a recess with a half-circle plan, its diameter equal to the width of the enclosing wall opening, and is typically covered by a semi-dome that follows the curve of the plan. This geometric form originated in Roman architecture and became a standard element in early Christian basilicas, providing a rounded termination to the nave.[36][37] Prevalent in basilican churches from the 4th to the 12th centuries, the semicircular apse offered simplicity in construction and inherent structural stability through its balanced load distribution, making it ideal for large-scale ecclesiastical buildings. A prime example is the Basilica of Sant'Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna, Italy, constructed in the 6th century under King Theodoric, where the apse's smooth curve housed the altar and originally featured mosaic decorations emphasizing its role as a liturgical focal point.[38][39] The design's advantages include a natural convergence of sightlines toward the altar, enhancing communal worship by drawing the congregation's gaze in a unified arc, and the ease of vaulting the semi-dome without requiring intricate pendentives or other transitions, which supported expansive interiors with minimal engineering complexity.[40][1] In the 6th-century Hagia Sophia in Constantinople, commissioned by Emperor Justinian I, the apse's expansive semicircular form—capped by a semi-dome adorned with golden mosaics—creates a dramatic curve that amplifies light and space, serving as the eastern terminus of the basilica plan and underscoring the form's capacity for symbolic and optical grandeur.[41] This evolved from Roman basilical precedents briefly noted in ancient origins.Polygonal Apse

The polygonal apse represents a faceted variation of the traditional apse design, characterized by an exterior composed of multiple straight sides—typically ranging from three to seven—while the interior features a continuous curved vault, often semicircular or domed. This geometric configuration first emerged in Carolingian architecture during the 8th and 9th centuries, marking a shift toward more complex forms that accommodated innovative spatial arrangements.[42] The multi-sided structure enabled the seamless attachment of radiating chapels around the ambulatory, expanding the functional and symbolic space at the church's eastern end without compromising the overall basilican layout.[43] During the Romanesque and Gothic periods, the polygonal apse gained widespread adoption to convey grandeur and liturgical prominence, evolving from Carolingian precedents into a hallmark of elaborate ecclesiastical design. In Romanesque architecture, it allowed builders to articulate the sanctuary with decorative arcading and sculptural detail, as seen in the Minster in Roermond, Netherlands, where the 13th-century polygonal apse integrates dwarf galleries and enhances the building's monumental scale.[44] By the Gothic era, this form supported heightened aesthetic and symbolic ambitions, emphasizing verticality and divine light. One key structural advantage of the polygonal apse lies in its compatibility with ambulatories and radiating chapels, which distribute the lateral thrust from ribbed vaults more evenly across multiple supports, facilitating taller elevations and the use of expansive glazing.[45] This even load distribution proved essential in Gothic constructions, where flying buttresses could anchor effectively to the faceted exterior, stabilizing the high vaults without excessive wall thickness. A premier Gothic exemplar is Chartres Cathedral in France, constructed primarily in the early 13th century, whose seven-sided apse encircles an ambulatory with five radiating chapels, optimizing the interplay of architecture and illumination. The polygonal facets accommodate tall lancet windows filled with stained glass, diffusing colored light throughout the choir to evoke a celestial ambiance central to Gothic spirituality.[45]Other Forms

Rectangular or square apses represent rare early forms in Syrian church architecture, particularly in the hall churches of northern Syria during the 5th century, where they served as simple, transitional sanctuaries before the widespread adoption of curved designs. These structures, often found in the Limestone Massif region among the "Dead Cities," featured a rectangular chancel integrated into the overall basilica or hall plan, emphasizing functional simplicity over decorative projection. For instance, hall churches in this area commonly employed rectangular apses to house the altar, reflecting local building traditions influenced by pre-Christian architecture and practical stonework constraints.[46] Horseshoe or trefoil apses emerged in Mozarabic architecture in Spain during the 10th century, incorporating Islamic-influenced curved forms that blended Visigothic and Umayyad elements into Christian church design. These apses typically featured a rounded, horseshoe-shaped interior profile, often flanked by side chapels, creating a hybrid aesthetic that symbolized cultural synthesis under Muslim rule. A prominent example is the Church of San Miguel de Escalada near León, constructed around 912–913, where the main apse adopts a horseshoe contour internally, supported by colonnades of similar arches, while the exterior maintains a more austere rectangular outline. This design not only facilitated liturgical space but also echoed the ornamental arches seen in Cordoban mosques, adapting them for ecclesiastical use.[47][48] Secular or modern hybrids adapt apse-like niches into non-religious contexts, such as assembly halls or theaters, where semicircular hemicycles provide focused spatial organization reminiscent of ecclesiastical sanctuaries. In parliamentary architecture, these forms promote communal deliberation by arranging seats in a curved array around a central podium. The hemicycle of the French National Assembly in the Palais Bourbon, Paris, exemplifies this, featuring a semicircular chamber designed in 1807 by architect Bernard Poyet, which draws on ancient Roman theater models to seat 577 deputies in a unified, apse-inspired layout. Such adaptations highlight the apse's enduring role in structuring group interaction beyond sacred spaces.[49] Absidioles, or small secondary apses, project from the aisles or encircle the main apse in larger churches, offering auxiliary chapels for side altars or relics while maintaining functional similarity to the primary sanctuary. Typically semicircular or polygonal in plan, they enhance the chevet's complexity without dominating the central axis. In Romanesque architecture, absidioles appear in ambulatory designs, as seen in the Abbey Church of Saint-Sever in Gascony, France (11th century), where six such chapels radiate around the main apse, creating a rhythmic enclosure for processions and devotions. These elements, distinct from the main apse by their scale and peripheral placement, supported polycentric liturgical practices in monastic and pilgrimage settings.[50]Related Architectural Elements

Chancel and Sanctuary

The chancel constitutes the eastern portion of a church, positioned between the nave and the apse, serving as a dedicated space for clergy and choir during liturgical services.[51] This area typically features a screening element, such as a rail or latticework derived from the Latin cancelli meaning "grating," which delineates it from the nave reserved for the congregation.[52] The chancel's design evolved from early Christian partitions, with evidence of chancel barriers and screens emerging as early as the 4th century to separate sacred clerical functions from the laity, as seen in early Christian, Byzantine, and later Anglo-Saxon structures.[53] Within the chancel lies the sanctuary, recognized as the most sacred zone of the church, often encompassing or directly adjoining the apse to house the high altar, tabernacle, and essential liturgical items like the Gospel book and candles.[54] In Byzantine architecture, the sanctuary frequently incorporates a raised platform, such as the tiered synthronon—a semicircular seating arrangement carved into the apse wall—providing benches for clergy and a central cathedra for the bishop, symbolizing hierarchical participation in the divine liturgy.[55] This elevation underscores the sanctuary's role as the focal point for the Eucharist, where the consecration of bread and wine occurs, evoking Christ's sacrifice and the heavenly banquet.[56] Functionally, the chancel acts as a transitional zone facilitating clerical processions from the nave toward the altar, enabling orderly movement during rites while maintaining spatial hierarchy.[57] In contrast, the sanctuary remains the exclusive domain for the Eucharistic celebration, distinct from the apse's primary role as an architectural recess terminating the church's eastern axis. Medieval rood screens further reinforced this division, serving as ornate barriers—often of stone or wood with carved figures—to separate the laity in the nave from the chancel's holy activities, thereby preserving the mystery of the sacraments.[52] A prominent example is the 15th-century stone rood screen at York Minster, adorned with statues of English kings, which not only demarcated spaces but also supported liturgical functions like choral performances.[58]Ambulatory and Chevet

The ambulatory is a covered, curving passageway that extends the aisles around the apse and choir at the eastern end of a church, permitting worshippers and pilgrims to circulate behind the main altar without disrupting services in the sanctuary.[59] This design element originated in the late 10th and early 11th centuries within monastic churches of the Romanesque period, where it addressed the growing need for structured movement in religious complexes housing relics and attracting devotees.[60] The chevet represents the integrated eastern complex of the apse, ambulatory, and a series of radiating chapels—often numbering five or seven—that project outward like spokes, creating a multi-axial arrangement that deepens the spatial composition of the church.[59] A prominent 13th-century example is the chevet of Reims Cathedral in France, where the ambulatory connects to radiating chapels dedicated to relic veneration, allowing devotees to approach sacred objects housed in side altars while maintaining the sanctity of the central space.[61] Functionally, the ambulatory and chevet facilitated pilgrimage by providing efficient pathways to peripheral chapels containing relics, enabling large crowds to view and honor them without interfering with liturgical activities at the high altar—a critical adaptation in medieval churches along routes like the Way of Saint James.[62] This arrangement enhanced the perceptual depth and luminosity of Gothic interiors, particularly through innovations like ribbed vaults and stained glass that Abbot Suger introduced in the ambulatory of Saint-Denis around 1140.[59] Evolutionarily, early ambulatories appeared in simpler forms during the Carolingian revival and early Romanesque era, as seen in the 12th-century chevet of the Abbey Church of Sainte-Foy at Conques, where the curving aisle supported modest radiating chapels around the apse for relic display amid monastic pilgrimage traffic.[62] By the High Gothic period, these evolved into more elaborate configurations in French rayonnant styles, exemplified by the refined, light-filled chevets of cathedrals like Reims, which integrated advanced vaulting to amplify the sense of divine radiance and accommodate intensified relic cults.[61]References

- https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/apse